Abstract

Background

The effectiveness of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug ketorolac in reducing pulmonary morbidity following rib fractures remains largely unknown.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study spanning January, 2003 to June, 2011, comparing pneumonia within 30 days and potential adverse effects of ketorolac among all patients with rib fractures who received ketorolac within four days post-injury to a random sample of those who did not.

Results

Among 202 patients who received ketorolac and 417 who did not, ketorolac use was associated with decreased pneumonia [odds ratio 0.14 (95% confidence interval 0.04–0.46)] and increased ventilator- and intensive care unit-free days [1.8 (95% confidence interval 1.1–2.5) and 2.1 (95% confidence interval 1.3–3.0) days, respectively] within 30 days. The rates of acute kidney injury, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and fracture non-union were not different.

Conclusions

Early administration of ketorolac to patients with rib fractures is associated with a decreased likelihood of pneumonia, without apparent risks.

Keywords: rib fractures, analgesia, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, ketorolac, pneumonia, pulmonary complication

INTRODUCTION

Rib fractures are a common manifestation of blunt thoracic injury, with approximately 10% of hospitalized trauma patients sustaining radiographically apparent fractures.1, 2 The mortality of such patients ranges from 3 to 13%, attributable both to associated injuries and pulmonary complications.2–4 The elderly are particularly susceptible to these complications,5 with about 13–30% developing pneumonia.6, 7

Despite their prevalence, there are few rigorous evaluations of the treatment of rib fractures. Typical measures include breathing exercises and other maneuvers to improve pulmonary hygiene and pain control using opiates and epidural analgesia.8 Local and regional rib blocks, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and slow infusion of local analgesics from a subcutaneous pump have been reported8–11 but are used less commonly. Opioids cause drowsiness and decreased respiratory effort that can promote atelectasis. Epidural infusions appear to decrease ventilator days and pneumonia rates.4, 12–14 However, in practice, epidural catheters frequently cannot be used: Over 70% of patients with three or more rib fractures who were screened for participation in a randomized trial evaluating epidural analgesia either had a contraindication to or refused epidural placement.12 Moreover, epidural catheter placement and maintenance are resource-intensive and can cause rare but serious complications like epidural hematomas and meningitis.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are often used as an adjunct to other analgesics. They are inexpensive and usually well tolerated. Their mechanism of action involves inhibition of cyclooxygenase, thus decreasing prostaglandin synthesis and limiting activation of pain receptors at the site of injury. Ketorolac is a potent member of this class that reduces post-operative pain.15, 16 Numerous studies demonstrate a decrease in opiate requirements when non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are added to post-thoracotomy analgesic regimens.17–25 Such patients also report better pain control and increased respiratory function with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.26, 27 However, injured patients may be at increased risk for known adverse effects of these medications, including hemorrhage (gastrointestinal or otherwise) and acute kidney injury, as well as hypothesized risks, such as fracture non-union28 and impaired soft tissue healing.29 While physicians often prescribe non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to patients with rib fractures, their effectiveness and safety have not been well studied for this particular indication.

In this study, we set out to determine whether ketorolac, when used as an adjunct for pain control in patients with rib fractures, is associated with decreased likelihood of pneumonia.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a single-center retrospective cohort study. We hypothesized that administration of ketorolac early after injury would decrease the likelihood of developing pneumonia during the first 30 days of hospitalization. The University of California Davis Institutional Review Board approved of our planned study before we commenced.

Study Setting and Population

We identified hospitalized trauma patients using our center’s trauma registry. We included patients hospitalized from January 1, 2003 to June 30, 2011 who had an International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, Clinical Modification discharge diagnosis of rib fracture(s) (807.0x; 807.1x; 807.2–807.4). (Because discharge diagnoses are coded primarily on the basis of physician documentation, these diagnoses do not necessarily require radiographic confirmation.) We excluded patients less than 18 years of age and those who died within 48 hours of arrival. We electronically linked the trauma registry records to inpatient pharmacy records to determine which patients received ketorolac. On an a priori basis, we defined ketorolac exposure as requiring both: (1) administration of the first dose of ketorolac within 96 hours of presentation, and (2) continuation of ketorolac for a minimum of 24 hours. We defined control status by the same criteria as ketorolac exposure [adults with a diagnosis of rib fracture(s) who survived ≥48 hours], except that they did not receive any ketorolac during their hospitalization. (Thus, implicitly, we excluded from the analysis patients who otherwise met control criteria but first received ketorolac ≥96 hours after presentation or received ketorolac for <24 hours.) We identified 202 ketorolac-exposed patients, and we planned to compare them to a random sample of control patients in an approximately 2:1 control:ketorolac ratio.

Data Collection

Two abstractors (YY, JY) (who were not blinded to the study hypothesis) recorded additional data from electronic and paper medical records using a pre-tested electronic abstraction instrument through REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) software.30 We verified information from the trauma registry (demographic data, mechanism of injury, Injury Severity Score, and Abbreviated Injury Scale scores) and recorded admission creatinine, comorbidities (congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease), history of smoking, presence of pleuritic chest pain, number of radiographically apparent rib fractures, use of epidural analgesia, and administration of any non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs other than ketorolac. For patients in the ketorolac group, we recorded the time of initial dose, duration of continuous use, starting dose, total cumulative dose, and route of administration.

Outcomes

We defined the primary outcome as an attending physician diagnosis of pneumonia on or after hospital day 2 (to restrict cases to hospital-acquired pneumonia) but within 30 days of presentation. For each case of pneumonia, we recorded the presence of a focal infiltrate on chest radiograph, fever (≥38.5°C) or hypothermia (<35°C), leukocytosis (>10,000 white blood cells/mm3) or leukopenia (<3,000 cells/mm3), purulent sputum, cultures of a pathologic organism, and duration of antibiotics.

To conduct a sensitivity analysis, we also assessed three alternative definitions of pneumonia: (1) attending diagnosis on or after hospital day 4 (rather than 2) but within 30 days of presentation (to ensure that the cases were hospital-acquired); (2) attending diagnosis that also met American Thoracic Society criteria for pneumonia (to minimize subjectivity in the diagnosis): focal infiltrate on chest radiograph, plus two of three clinical features (fever greater than 38°C, leukocytosis or leukopenia, and purulent secretions);31 and (3) diagnosis as determined by our hospital’s quality improvement committee. The latter assessment, though based in part on physician diagnoses, was completely independent of this study and blinded from the primary outcome as determined by our study team.

We assessed use of epidural analgesia and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs besides ketorolac as possible co-interventions. We determined 30-day ventilator-free days, 30-day intensive care unit-free days, and 90-day mortality as secondary outcomes.

We recorded the occurrence of acute kidney injury [as defined by the Acute Kidney Injury Network: an absolute increase in serum creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dL (≥26.4 μmol/L) or an increase in serum creatinine ≥50% from baseline32], gastrointestinal bleeding, myocardial infarction, and stroke within 30 days of presentation as potential complications. We also assessed whether non-union of a long bone fracture occurred within 180 days of presentation.

Analysis

Assuming the risk of pneumonia without ketorolac was 10%, we determined that we would be able to detect a reduction in the absolute risk of pneumonia with ketorolac to 3.8% or less with 80% power at the 0.05 alpha level if we evaluated the 202 ketorolac subjects in a 2:1 control:ketorolac ratio.

We compared baseline characteristics between the groups using the t- and Chi-square tests. We evaluated the primary outcome using multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for covariates which we selected on an a priori basis: the number of rib fractures, Abbreviated Injury Scale chest and extremity scores, and presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. We included both the number of rib fractures and Abbreviated Injury Scale chest score because each characterizes different aspects of chest injuries; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as an important predictor of pneumonia risk; and Abbreviated Injury Scale extremity score because the orthopedic surgeons at our center tend to discourage use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with long bone fractures, which may contribute to pneumonia risk as a result of immobility.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome by examining the association of ketorolac administration with the three aforementioned alternative definitions of pneumonia. We characterized the inter-rater reliability of our assessment of the primary outcome with the quality improvement committee’s assessment using the kappa (κ) statistic.

We used multivariable Poisson regression (and linear regression, for greater interpretability) to determine the association of ketorolac with 30-day ventilator-free days and 30-day intensive care unit-free days, adjusting for the same covariates as the model involving the primary outcome. We compared complications between the two groups (acute kidney injury, myocardial infarction, stroke, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, fracture non-union, and death) using logistic regression. We inferred the absence of complications if the last follow-up time was subsequent to the time frame of interest and there was no mention of a complication in the medical record; if follow-up ceased before the time frame closed, we assumed that no additional outcomes occurred.

We conducted all analyses using Stata, version 10.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). We used two-tailed tests with an alpha level of 0.05.

RESULTS

We abstracted records for 417 control hospitalizations, which we compared to the 202 comprising the ketorolac group. All patients had either radiographic evidence of rib fractures or pleuritic pain on physical exam. The average age of the combined cohort was 48 ± 18 years and the average Injury Severity Score 12 ± 9 (Table 1). Motor vehicle collisions accounted for more than 50% of the hospitalizations in both groups. Abbreviated Injury Scale head and abdomen scores were greater in the control group. Abbreviated Injury Scale chest scores, presence of radiographic rib fractures, total number of ribs fractured, comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and current smoking all were significantly greater in the ketorolac group. The control group included more patients with chronic kidney disease and had a slightly higher initial creatinine level.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 619 patients with rib fractures who received or did not receive ketorolac within the first four days after injury.

| Characteristic | Control (N=417) | Ketorolac (N=202) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± standard deviation) | 48 ± 19 | 48 ± 16 | 0.89 |

| Male, n (%) | 258 (62) | 118 (58) | 0.47 |

| Mechanism, n (%) | 0.66 | ||

| Blunt | 402 (96) | 195 (96) | |

| Motor vehicle collision | 237 (56) | 104 (51) | |

| Motorcycle collision | 28 (7) | 21 (10) | |

| Auto versus pedestrian/bike | 36 (9) | 15 (7) | |

| Fall | 72 (17) | 40 (20) | |

| Assault | 29 (7) | 15 (7) | |

| Penetrating | 11 (3) | 3 (1) | |

| Other | 7 (2) | 4 (2) | |

| Abbreviated Injury Scale scores | |||

| Head [median (interquartile range)] | 2 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.01 |

| Face [median (interquartile range)] | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.53 |

| Chest (mean ± standard deviation) | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Abdomen [median (interquartile range)] | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.04 |

| Extremity [median (interquartile range)] | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 2) | 0.41 |

| External [median (interquartile range)] | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) | 0.16 |

| Injury Severity Score (mean ± standard deviation) | 12 ± 10 | 12 ± 7 | 0.99 |

| Radiographic rib fracture, n (%) | 200 (48) | 139 (69) | <0.001 |

| Number of radiographic rib fractures [median (interquartile range)], all subjects * | 0 (0, 2) | 2 (0, 4) | <0.001 |

| Number of radiographic rib fractures [mean ± standard deviation], subjects with ≥1 such fracture † | 3.1 ± 2.3 | 3.7 ± 2.6 | 0.02 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 7 (2) | 5 (2) | 0.50 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 7 (2) | 9 (4) | 0.04 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 12 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.02 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 60 (14) | 69 (34) | <0.001 |

| Initial creatinine, mg/dL (mean ± standard deviation) | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.01 |

Includes subjects who did not have any radiographic rib fractures (i.e., the patient experienced pleuritic pain but did not have any apparent fractures on chest x-ray or, if available, CT scan)

Includes only the 200 control and 139 ketorolac subjects who had radiographic rib fracture(s)

In the ketorolac group, the mean time to the first dose of ketorolac was 1.6 ± 0.9 days with an average continuous duration of 2.2 ± 1.7 days. The mean cumulative dose was 132 ± 70 mg, all administered via the intravenous route. Eight-one percent of patients received an initial dose of 15 mg, with the remainder receiving 30 mg. Clinicians administered other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to 23 patients (11%) in the ketorolac group and 11 (3%) in the control group (p<0.001). Twelve patients in the control group and three in the ketorolac group had an epidural catheter placed for analgesia.

We identified 24 patients with pneumonia documented by an attending physician during hospital days 2–30, including 19 in the control group and 5 in the ketorolac group. Most cases involved a radiographic infiltrate (79%), leukocytosis (92%), and purulent sputum (79%). There were no significant differences in the proportions of patients with pneumonia in the control and ketorolac groups that had a chest x-ray infiltrate (74 vs. 100%, respectively), fever or hypothermia (58 vs. 40%), leukocytosis or leukopenia (89 vs. 100%), purulent sputum (74 vs. 100%), a positive culture (58 vs. 40%), or ventilator-associated pneumonia (79 vs. 40%). The time from injury to pneumonia diagnosis was 6 ± 4 days among control subjects and 8 ± 2 days among ketorolac subjects (p=0.33). Antibiotics were administered in all cases, with a mean duration of 8 ± 4 days in the control group and 6 ± 1 days in the ketorolac group (p=0.15).

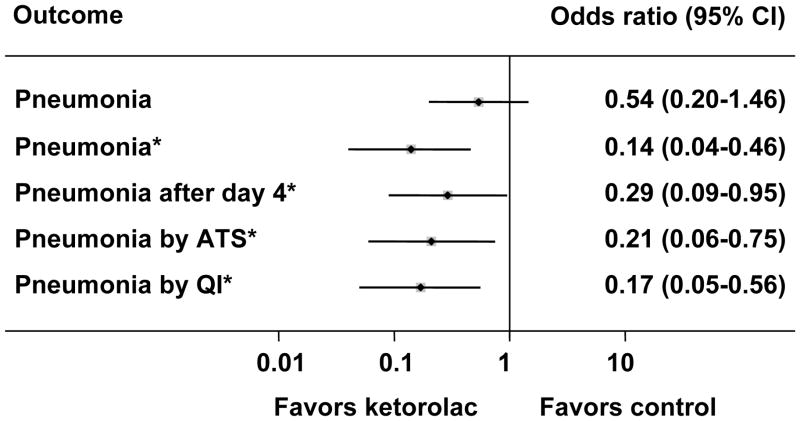

The unadjusted odds ratio of pneumonia with ketorolac was 0.54 (95% confidence interval 0.20–1.46). After adjustment for the number of rib fractures, Abbreviated Injury Scale chest and extremity scores, and comorbid chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the odds ratio decreased to 0.14 (95% confidence interval 0.04–0.46) (Figure 1). Six cases of pneumonia in the control group (and none in the ketorolac group) occurred on hospital day two or three, and six cases in the control group (and none in the ketorolac group) failed to meet American Thoracic Society criteria. Our hospital’s quality improvement committee classified three cases in the control group (and again none in the ketorolac group) as pneumonitis rather than pneumonia. Nonetheless, these alternative definitions of pneumonia did not substantially change the magnitude of association of ketorolac with pneumonia (Figure 1). Additional adjustment for age and sex had no effect on the observed association for any of the definitions of pneumonia. Inter-rater agreement between our study team’s and the quality improvement committee’s ascertainment of pneumonia was excellent (κ=0.93).

Figure 1.

The association of ketorolac with decreased likelihood of pneumonia within 30 days of injury. Results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals, and the asterisks (*) indicate that the odds ratios are adjusted for the number of rib fractures, Abbreviated Injury Scale chest and extremity scores, and the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. “Pneumonia by ATS” refers to diagnoses of pneumonia that met the American Thoracic Society criteria, and “Pneumonia by QI” refers to diagnoses of pneumonia ascertained by a hospital quality improvement committee blinded to this study.

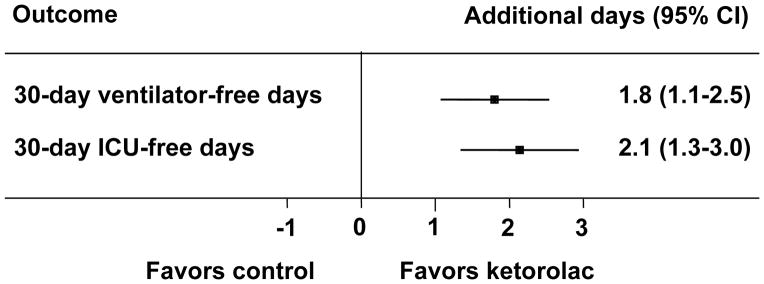

With and without adjustment for confounding factors, both Poisson and linear regression modeling suggested that ketorolac was associated with increased ventilator- and intensive care unit-free days within the first 30 days after presentation. In the adjusted Poisson regression model, ketorolac was associated with a 6% (95% confidence interval 2–9%) increase in time alive and off of the ventilator and a 7% (95% confidence interval 4–11%) increase in time alive and not in the intensive care unit. In the adjusted linear regression model, ketorolac was associated with 1.8 (95% confidence interval 1.1–2.5) more days alive and off of the ventilator and 2.1 (95% confidence interval 1.3–3.0) more days alive and not in the intensive care unit (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The association of ketorolac with increased ventilator- and intensive care unit (ICU)-free days within 30 days of injury. Results are presented as the differences with 95% confidence intervals, adjusted for the number of rib fractures, Abbreviated Injury Scale chest and extremity scores, and the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Important adverse events potentially related to ketorolac use appeared to be rare, with no obvious differences between the groups in the occurrence of acute kidney injury, myocardial infarction, stroke, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and fracture non-union (Table 2). Seven deaths occurred in the control group and none in the ketorolac group (p=0.06, Fisher’s exact test).

Table 2.

Adverse outcomes among 619 patients with rib fractures who received or did not receive ketorolac within the first four days after injury.

| Adverse outcome | Control (N=417) | Ketorolac (N=202) | Odds ratio* (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute kidney injury, n (%) | 19 (5) | 6 (3) | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | — |

| Stroke, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | — |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, n (%) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.1–22.3) |

| Fracture non-union, n (%) | 3 (0.7) | 2 (1) | 2.3 (0.3–15.6) |

| Death, n (%) | 7 (2) | 0 (0) | 6.2 (0.5–76.4) |

Adjusted for the number of rib fractures, Abbreviated Injury Scale chest and extremity scores, and the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that administration of ketorolac early after injury significantly decreases the risk of pneumonia among patients with rib fractures. It also appeared to reduce time on the ventilator and in the intensive care unit without any prominent increase in such known or hypothesized risks of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as acute kidney injury, myocardial infarction, stroke, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or fracture non-union. Because pneumonia was a relatively rare outcome, the odds ratio approximates the relative risk, suggesting possibly a seven-fold reduction in risk of pneumonia with ketorolac use. This degree of risk reduction—and the lack of an increase in adverse effects, including fracture non-union in this and other analyses28—suggests that efforts to control pain with ketorolac should prevail over concerns about its orthopedic effects in injured patients.

Though non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been studied extensively in other settings, relatively few studies have examined their effectiveness in controlling pain or reducing pulmonary morbidity following rib fractures. Several studies have focused on regional techniques for pain control after rib fractures but few have been methodologically rigorous enough to support broad practice changes.9 Bulger et al. concluded from their randomized trial of patients with multiple rib fractures that epidural use decreased the risk of pneumonia and time on the ventilator, though the size of the study was modest and the findings were significant only in an adjusted analysis.12 Furthermore, contraindications to epidural analgesia are frequent among injured patients, begging the question of which intervention(s) are best when it is not an option.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs clearly reduce pain and opioid use following thoracic, orthopedic, and abdominal operations.15 Among post-thoracotomy patients, some studies have also shown better postoperative pulmonary function or improved pain control during breathing exercises with ketorolac or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.17, 18, 26, 27 Although we could not characterize pain severity or pulmonary function well from review of medical records in this study, these benefits may explain why ketorolac was associated with reduced pneumonia.

We used an inclusive definition of rib fractures in which we considered pleuritic pain sufficient to make the diagnosis because 50% or more of rib fractures may be missed on plain chest x-rays.33 This may explain the relatively low rate of pneumonia we observed (2.5% in the ketorolac group and 4.6% in the control group) as most studies have focused on patients with radiographically apparent fractures. However, with restriction to the subpopulations evaluated in other studies, we observed a comparable incidence: Among patients with three or more fractured ribs, approximately 8% of patients less than 65 years of age and 17% of those 65 or older developed pneumonia.

We defined the ketorolac group based on receiving the medication within the first four days post-injury both to ensure that it was administered during a relevant time frame for prevention of pneumonia and because inflammation typically peaks within the first few days post-injury. We excluded patients who received ketorolac for less than 24 hours on the grounds that such limited administration would be unlikely to have a significant clinical effect. The ketorolac doses we observed were much lower than the maximal safe dose of 30 mg intravenously every six hours for five days as described in the medication package insert. This and the fact that our study had minimal power to detect rare events may explain why we did not detect adverse effects of ketorolac.

The diagnosis of pneumonia is fraught with uncertainty.31 For the primary outcome we used an attending physician diagnosis because it is likely the most relevant criterion standard at our center. Our trauma surgery service only infrequently obtained distal airway invasive cultures (bronchoscopic or blind technique) in either ventilated or non-ventilated patients with suspected pneumonia during the study period; thus, the fact that only 54% of pneumonia cases were microbiologically confirmed is not surprising. In the absence of microbiologic confirmation from the distal airway, we felt that attending physician judgment was the best option to minimize non-specificity from clinical criteria and cultures of the proximal airway. In practical terms, all 24 patients diagnosed with pneumonia were treated as such. Furthermore, alternative definitions of the primary outcome—whether by restricting cases to those with an attending physician diagnosis and that met American Thoracic Society clinical criteria or as ascertained by our hospital’s quality improvement committee—confirmed our primary findings. Nonetheless, evaluation of ketorolac in a setting that uses routine invasive diagnosis of pneumonia would be worthwhile.

The ketorolac and control patients were similar in several characteristics, including age and sex, but the characteristics that differed tended, if anything, to promote pneumonia in the ketorolac group. Patients who received ketorolac had a greater Abbreviated Injury Scale chest score, a greater likelihood of radiographic rib fractures, more rib fractures, and greater prevalence of smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Treating physicians may have used ketorolac to be more aggressive in managing the pain of these higher-risk patients. Accordingly, the reduction in the risk of pneumonia associated with ketorolac only became more impressive with adjustment for these imbalances. The control group had greater Abbreviated Injury Scale head and abdomen scores as well as initial creatinine levels and prevalence of chronic kidney disease. We postulate that these differences reflect reluctance to risk potential bleeding and renal impairment from ketorolac. However, post hoc adjustment for these differences did not change the association of ketorolac with a reduced risk of pneumonia (analyses not shown).

Our study has limitations. As a non-randomized comparison, it may involve residual confounding from hidden differences or selection biases that we could not conceptualize or measure retrospectively. Time-dependent co-interventions such as ventilator use, opioids, and other analgesic measures are particularly hard to tease apart from the effects of ketorolac. Partly because the effects of ketorolac could be partially mediated by the use or non-use of these other interventions, we did not attempt to account for these factors in our analyses. However, even a construct of baseline opiate use (e.g., during the first 24 hours) would be a problematic surrogate for the pain the patient experiences because it can be influenced by non-chest wall injuries, the mental state of the patient, and other factors that have little or no relationship to chest wall pain. Alternatively, epidural catheter and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use both were infrequent enough that they appeared to have little influence on the risk of pneumonia in our cohort. These issues and the aforementioned challenges of using pneumonia as an outcome emphasize that our study should be considered more a source of future study hypotheses than definitive evidence. If ketorolac indeed reduces the risk of pneumonia seven-fold, even if pneumonia were an infrequent outcome, future randomized trials may be able to detect such a difference with enrollment of approximately 500–800 subjects.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this comparison is the first to evaluate the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs specifically for patients with rib fractures. It suggests that early administration of ketorolac is associated with a decreased likelihood of pneumonia, increased ventilator-free days, and increased intensive care unit-free days, all without a notable increase in adverse effects.

SUMMARY.

The effectiveness of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug ketorolac in reducing pulmonary morbidity following rib fractures remains largely unknown. In this retrospective cohort study of 202 patients who received ketorolac and 417 who did not, ketorolac use was associated with decreased pneumonia [odds ratio 0.14 (95% confidence interval 0.04–0.46)] and increased ventilator- and intensive care unit-free days [1.8 (95% confidence interval 1.1–2.5) and 2.1 (95% confidence interval 1.3–3.0) days, respectively] within 30 days, without apparent adverse events such as acute kidney injury, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or fracture non-union.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the University of California Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center for assistance with data management.

This publication was made possible by Grant Number UL1 RR024146 from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Center for Research Resources or National Institutes of Health. Information on the National Center for Research Resources is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp.

Footnotes

Reprints will not be made available by the authors.

We presented findings from this study at the Surgical Forum, American College of Surgeons Annual Clinical Congress, October 3, 2012, in Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Mayberry JC, Trunkey DD. The fractured rib in chest wall trauma. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1997;7:239–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziegler DW, Agarwal NN. The morbidity and mortality of rib fractures. J Trauma. 1994;37:975–9. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199412000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirmali M, Turut H, Topcu S, et al. A comprehensive analysis of traumatic rib fractures: morbidity, mortality and management. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24:133–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wisner DH. A stepwise logistic regression analysis of factors affecting morbidity and mortality after thoracic trauma: effect of epidural analgesia. J Trauma. 1990;30:799–804. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199007000-00006. discussion 804–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holcomb JB, McMullin NR, Kozar RA, et al. Morbidity from rib fractures increases after age 45. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:549–55. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01894-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnea Y, Kashtan H, Skornick Y, et al. Isolated rib fractures in elderly patients: mortality and morbidity. Can J Surg. 2002;45:43–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulger EM, Arneson MA, Mock CN, et al. Rib fractures in the elderly. J Trauma. 2000;48:1040–6. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200006000-00007. discussion 1046–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho AM, Karmakar MK, Critchley LA. Acute pain management of patients with multiple fractured ribs: a focus on regional techniques. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:323–7. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328348bf6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karmakar MK, Ho AM. Acute pain management of patients with multiple fractured ribs. J Trauma. 2003;54:615–25. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000053197.40145.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karmakar MK, Critchley LA, Ho AM, et al. Continuous thoracic paravertebral infusion of bupivacaine for pain management in patients with multiple fractured ribs. Chest. 2003;123:424–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oncel M, Sencan S, Yildiz H, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for pain management in patients with uncomplicated minor rib fractures. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:13–7. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulger EM, Edwards T, Klotz P, et al. Epidural analgesia improves outcome after multiple rib fractures. Surgery. 2004;136:426–30. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrier FM, Turgeon AF, Nicole PC, et al. Effect of epidural analgesia in patients with traumatic rib fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2009;56:230–42. doi: 10.1007/s12630-009-9052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu CL, Jani ND, Perkins FM, et al. Thoracic epidural analgesia versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia for the treatment of rib fracture pain after motor vehicle crash. J Trauma. 1999;47:564–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199909000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moote C. Efficacy of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the management of postoperative pain. Drugs. 1992;44 (Suppl 5):14–29. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199200445-00004. discussion 29–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joris J. Efficacy of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 1996;47:115–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavy T, Medley C, Murphy DF. Effect of indomethacin on pain relief after thoracotomy. Br J Anaesth. 1990;65:624–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/65.5.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keenan DJ, Cave K, Langdon L, et al. Comparative trial of rectal indomethacin and cryoanalgesia for control of early postthoracotomy pain. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983;287:1335–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.287.6402.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senard M, Deflandre EP, Ledoux D, et al. Effect of celecoxib combined with thoracic epidural analgesia on pain after thoracotomy. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:196–200. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Cosmo G, Aceto P, Gualtieri E, et al. Analgesia in thoracic surgery: review. Minerva Anestesiol. 2009;75:393–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koehler RP, Keenan RJ. Management of postthoracotomy pain: acute and chronic. Thorac Surg Clin. 2006;16:287–97. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCrory C, Diviney D, Moriarty J, et al. Comparison between repeat bolus intrathecal morphine and an epidurally delivered bupivacaine and fentanyl combination in the management of post-thoracotomy pain with or without cyclooxygenase inhibition. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16:607–11. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2002.126957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carretta A, Zannini P, Chiesa G, et al. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine and extrapleural intercostal nerve block on post-thoracotomy pain. A prospective, randomized study. Int Surg. 1996;81:224–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Power I, Bowler GM, Pugh GC, et al. Ketorolac as a component of balanced analgesia after thoracotomy. Br J Anaesth. 1994;72:224–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/72.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lippmann M, Ginsburg R. Ketorolac for post-thoracotomy pain relief. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:281. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.2.281-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh H, Bossard RF, White PF, et al. Effects of ketorolac versus bupivacaine coadministration during patient-controlled hydromorphone epidural analgesia after thoracotomy procedures. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:564–9. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199703000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rhodes M, Conacher I, Morritt G, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs for postthoracotomy pain. A prospective controlled trial after lateral thoracotomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodwell ER, Latorre JG, Parisini E, et al. NSAID exposure and risk of nonunion: a meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010;87:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9379-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Randelli P, Randelli F, Cabitza P, et al. The effects of COX-2 anti-inflammatory drugs on soft tissue healing: a review of the literature. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2010;24:107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livingston DH, Shogan B, John P, et al. CT diagnosis of Rib fractures and the prediction of acute respiratory failure. J Trauma. 2008;64:905–11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181668ad7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]