Abstract

The National Trajectory Project examined longitudinal data from a large sample of people found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder (NCRMD) to assess the presence of provincial differences in the application of the law, to examine the characteristics of people with serious mental illness who come into conflict with the law and receive this verdict, and to investigate the trajectories of NCRMD–accused people as they traverse the mental health and criminal justice systems. Our paper describes the rationale for the National Trajectory Project and the methods used to collect data in Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia, the 3 most populous provinces in Canada and the 3 provinces with the most people found NCRMD.

Keywords: forensic, mental health, National Trajectory Project, not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder, mental disorder, criminality, violence, review board

Abstract

Les membres du Projet national des trajectoires ont examiné les données longitudinales d’un vaste échantillon de personnes déclarées non criminellement responsables pour cause de troubles mentaux (NCRTM) afin d’évaluer la présence de différences provinciales en matière d’application de la loi, d’étudier les caractéristiques de personnes ayant une maladie mentale grave qui, ayant des démêlés avec la justice, sont déclarées non criminellement responsables, et d’examiner les trajectoires des accusés NCRTM à travers les systèmes de santé mentale et de justice pénale. Le présent document décrit la raison d’être du Projet national des trajectoires et les méthodes utilisées pour recueillir des données au Québec, en Ontario et en Colombie-Britannique, les 3 provinces les plus populeuses du Canada et celles où se trouve la majorité des personnes déclarées NCRTM.

There has been a dramatic growth in the rates of admissions to forensic mental health services in Europe and North America.1 In Europe, there has been a significant increase in the number of hospital beds and other resources dedicated to the forensic population.2 Seto et al3 reported similar findings in Ontario, and described data from the United States showing that an increasing number of psychiatric hospital beds were being occupied by forensic clients, a trend they called forensication of people with SMI. In short, research demonstrates it is increasingly easier to hospitalize someone with SMI, and access other mental health resources, after a criminal charge has been laid than it is to access mental health services through the civil psychiatric system.

The Canadian Context

In Canada, people find themselves in forensic institutions as a result of having been found unfit to stand trial (unable to participate in a criminal proceeding as a result of SMI or other mental disability) or following a verdict of NCRMD.4,5

In line with the common-law principle that it is inappropriate to punish people who did not have criminal intent at the time of the offence, section 16 of the Criminal Code defines the verdict of NCRMD as:

No person is criminally responsible for an act committed or an omission made while suffering from a mental disorder that rendered the person incapable of appreciating the nature and quality of the act or omission or of knowing that it was wrong.6

Review Boards

RBs are independent tribunals established to determine dispositions of accused found unfit to stand trial or NCRMD. At the time the study was conducted, the criteria that governed the RBs’ dispositions in section 672.54 of the Criminal Code required the following:

Where a court or Review board makes a disposition . . . it shall, taking into consideration the need to protect the public from dangerous persons, the mental condition of the accused, the reintegration of the accused into society and the other needs of the accused, make one of the following dispositions that is the least onerous and least restrictive to the accused.6

These dispositions are as follows: 1) absolute discharge; 2) conditional discharge (typically living in the community under conditions set by the RB); or 3) detention in hospital.

Highlights

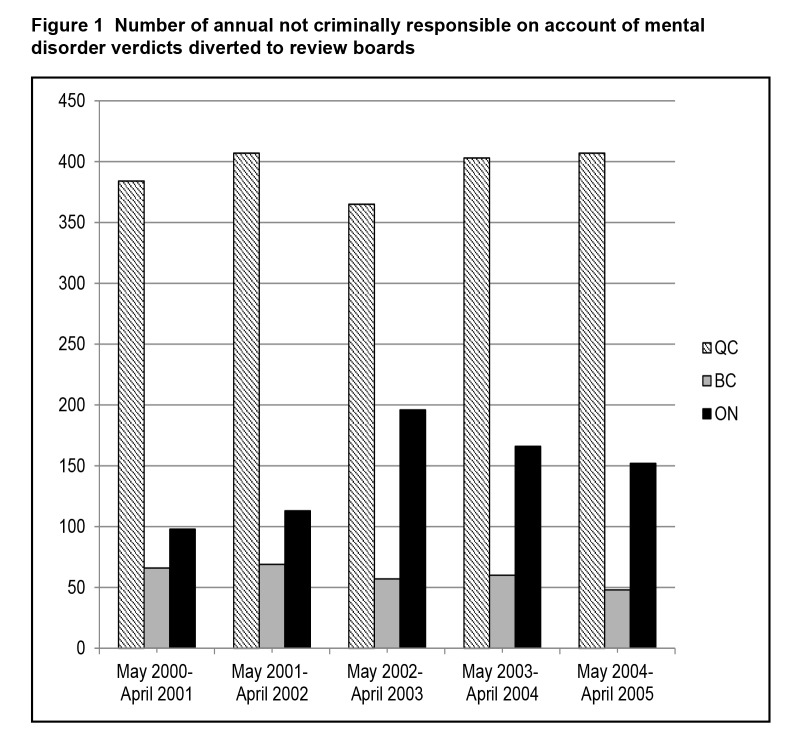

Significant interprovincial differences are observed in the number of people found NCRMD per criminal court verdict annually.

Different trends over time are observed across each province in the number of NCRMD–accused people entering the provincial RB systems.

Although there has been an overall national increase in the number of people found NCRMD in Canada,4 there are some interprovincial differences. In Quebec, there were more than twice as many NCRMD findings in 2005 (n = 407) as in 1992 (n = 177).7 In fiscal year 2011/12, there were 540 new verdicts of NCRMD in Quebec (Carmelle Beaulieu, May 9, 2013, personal communication). There also has been a steady increase in Ontario, with 170 new NCRMD–accused cases diverted to the RB in 2010–2011.5,8 However, some provinces, such as British Columbia, have seen smaller increases.5 After an initial increase in the early 1990s,9 the annual number of new NCRMD findings has been on a steady gradual decline in British Columbia since 1999. This suggests there are potentially important differences in the way that the law is being applied across provinces.

Organization of Forensic Mental Health Services

In Quebec, in addition to the provincial forensic psychiatric hospital, there are over 50 mental health settings designated to receive NCRMD–accused people. Thus many NCRMD–accused people are in custody of civil psychiatric hospitals that are not specialized for risk assessment and risk management. There is one interregional forensic services group and one Montreal intersectoral services group who meet regularly to ensure interagency communication and training.

British Columbia has a highly integrated network of forensic services. The BC FPSC is a multi-site organization that provides and coordinates specialized clinical services at the BC Forensic Psychiatric Hospital and 6 regional clinics across the province. All people sent for NCRMD or fitness assessments, as well as all people found unfit or NCRMD by the courts, are treated and managed by the FPSC.

The forensic mental health system in Ontario is different from British Columbia and Quebec. People found NCRMD are treated and managed by 1 of 10 designated forensic facilities for adults. These facilities operate independently, but the staff and services are specialized and their directors meet regularly through a forensic directors group, thereby informally coordinating services. Ontario represents a middle ground between forensic systems in Quebec (highly distributed, with many nonforensic professionals involved) and British Columbia (specialized and centrally coordinated by a single organization).

The National Trajectory Project

The main goals of the NTP10 were to provide a representative portrait of people found NCRMD during an extended period of time, and to examine their trajectories through the RB system. This study was conducted in the 3 most populated Canadian provinces: Ontario (39%), Quebec (23%), and British Columbia (13%),11 which also encompass most NCRMD cases4 and operate under different provincial forensic mental health service models.12,13

The primary objectives of the NTP were as follows:

Describe the demographic, psychosocial, and criminological profiles of NCRMD accused in Canada.

Evaluate the reporting of violence risk factors and assessments presented to the RBs.

Distinguish the rationales for RB dispositions.

Examine rehospitalization and recidivism outcomes.

Track the migration patterns of people found NCRMD.

Identify the individual and organizational factors associated with these geographic and processing trajectories.

Examine the use of mental health services by the accused people prior to the NCRMD verdict, under the RB, and following discharge.

Examine each of these findings with respect to culture and gender.

Learn how the Criminal Code and the RB process are perceived and experienced by people adjudicated NCRMD, their families, and professionals across Canada.

Methods

Design and Study Period

The NTP used a longitudinal design to study a cohort of people found NCRMD in British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec, retrospectively. The sample selection start date considered the Winko decision,14 which could have influenced the characteristics of NCRMD–accused people and RB decisions about absolute discharges.15 The study end date allowed for a minimum of a 3-year follow-up for all cases, up to a maximum of 8 years. Note, the Winko decision clarified that the verdict of NCRMD is neither one of guilt nor acquittal and further elaborated on the notion of significant threat to public safety and underlined the importance of the least restrictive and least onerous disposition.16,17

Sample Selection

The sample selection period spanned May 1, 2000, to April 30, 2005. Quebec had a significantly higher number of NCRMD verdicts per year than both Ontario and British Columbia (Figure 1). Averaged across 5 years, NCRMD verdicts accounted for 6.08 per 1000 decisions in Quebec criminal courts, compared with 0.95 in Ontario and 1.34 in British Columbia. No significant changes in the number of general criminal court cases were observed during this 5-year period.18 The number of NCRMD–accused people by province was also stable.

Figure 1.

Number of annual not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder verdicts diverted to review boards

For every person found NCRMD and under an RB, the first NCRMD verdict within the province’s time frame was identified as the index verdict. Owing to time and budgetary constraints, time frames varied across provinces.

In Quebec, there were a total of 2389 NCRMD verdicts between May 1, 2000, and April 30, 2005, corresponding to 1964 people. To obtain a geographically representative sample of all 17 justice administrative regions of Quebec, a random sampling procedure was applied for each region using a finite population correction factor. Therefore, the descriptive analyses are weighted.

The Ontario sample was comprised of all adults with an NCRMD verdict between January 1, 2002, and April 30, 2005 (n = 484). Data collection started with the same end date as Quebec and then files were coded backwards in time. Coding was completed to January 1, 2002. The British Columbia sample was comprised of 222 NCRMD–accused people registered with the BC RB between May 1, 2001, and April 30, 2005.

For the Quebec sample, preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure that potential differences between provinces would not be attributable to different data collection time frames. No statistically significant differences in the psychosocio-criminal characteristics of people found NCRMD in Quebec for the 2000 to 2002 and the 2002 to 2005 time frames were observed. Thus the full Quebec sample was used for all analyses.

In summary, the full population of people found NCRMD is represented for British Columbia and Ontario, whereas for Quebec, a random sample of people was selected, stratified by region. Normalized weights are attributed to the Quebec sample and the total sample when presenting total population rates. This normalized weighting may result in a slightly different number (±2) of valid cases in the various descriptive analyses because cell counts are rounded. The final national sample size was 1800.

Procedures

For each case, RB files 5 years prior to the index verdict were reviewed and then coded forward until December 31, 2008. In British Columbia, RB files dated before November 2001 had been destroyed; thus the 7 cases from May 2000 until October 31, 2001, were accessed from files kept at the British Columbia Forensic Psychiatric Hospital. The hospital files generally contain the same reports and documents found in RB files. Research assistants were instructed to code only from the file content that would have been generally found in RB files, to maintain comparability with other cases and the other provinces.

Trained research assistants coded and entered RB data into a bilingual computerized database to ensure standardization of data collection across study sites. Throughout the study, quality checks included meetings to discuss data collection issues. A password-protected blog was maintained on the NTP website to allow discussions between research assistants, project coordinators, and investigators about challenging or unusual cases.

Measures and Sources of Information

Five categories of information were coded: sociodemo-graphic information (for example, age at verdict, gender, and marital status); clinical information (for example, age at first psychiatric hospitalization, diagnosis at NCRMD verdict); criminal history (for example, offences leading to the index NCRMD verdict, past convictions, or NCRMD verdicts); details of the risk assessments presented at each RB hearing; contextual factors and processing through the RB system (for example, RB dispositions and associated reasons).

Psychopathology

Diagnoses were coded from court-ordered psychiatric evaluations for the index verdict and annual reports submitted to the RBs. Diagnoses were rarely identified using standard codes from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual19 or the International Classification of Diseases20 and often included nonstandard descriptors. Eight broad diagnostic categories were coded: psychosis; mood; organic (for example, dementia); anxiety; substance use; personality; other (for example, intellectual disabilities and autism); and none (the reports specify there is no diagnosis). Percentages add up to more than 100% because people could have more than 1 diagnosis.

In 8.1% (n = 153) of NCRMD assessments presented to the courts, no psychiatric diagnosis was mentioned. Therefore, we used psychiatric diagnoses from the 3 hearings following the verdict on the assumption that there would be less missing information at subsequent hearings; further clinical evaluation could clarify the primary diagnosis(es); and diagnosis would be stable over time. In 13 cases, no diagnostic information was available because no psychiatric evaluations were found in the RB files. Therefore, the distribution of diagnoses for this report was calculated on 1787 instead of 1800 people.

Police reports and other documents were also coded for psychiatric symptoms during the commission of the offence: unspecified psychotic symptoms, hallucinations, delusions, suicidal ideation, attempted suicide, self-harming behaviour, homicidal ideation, and substance use.

Risk Assessments

Research assistants coded the presence or absence of items from 2 widely used violence risk assessment tools (VRAG21 and HCR-2022) to ascertain the extent to which risk assessment measures were used and reported by clinicians to inform the RB dispositions and conditions.

Historical-Clinical-Risk Management-20

The HCR-2022 was used to structure coding of risk factors presented by clinicians to RBs. It has strong psychometric properties and has been studied and used internationally.23–27 It has also been validated in French.28 The 20 items on the HCR-20 are divided into 3 sections: H for 10 historical or static variables that do not or seldom change with time; C for 5 clinical variables that are amenable to intervention; and R for 5 risk management variables that should be the focus of attention to reduce violence. For our study, coding was modified to the following: present, absent, mentioned but uncodable, or not mentioned.

Violence Risk Appraisal Guide

The VRAG29–30 is a 12-item actuarial measure that uses historical information, such as offence history and victim characteristics, to estimate long-term risk of violence.21 The measure has very good interrater reliability, been validated in both forensic and correctional populations, and very good predictive accuracy.29–31 Though the VRAG items are usually weighted, they were coded as present, absent, mentioned but uncodable, or not mentioned for this study.

Research assistants coded whether HCR-20 or VRAG items were mentioned in clinical reports submitted to the RB. The intention of this approach was to examine what information clinicians brought as explicit evidence to the RBs. A limitation to this coding approach is that items could be considered by clinicians without being specifically mentioned. Moreover, there is an asymmetry of information because it is easier to code the presence of a factor than its absence, because the natural tendency is to mention presence (for example, “He has a history of substance use problems.”) rather than to specifically mention absences (for example, “There is no evidence he ever had substance use problems.”).

Interrater Reliability

A total of 1835 RB reports associated with 573 NCRMD–accused people were submitted to interrater reliability testing for the HCR-20 and the VRAG regarding the expert reports to the RBs and RB justifications for their decisions. For the expert reports to the RBs, the average kappa for the HCR-20 was 0.78 (0.84 for the H factor, 0.75 for the C factor, and 0.69 for the R factor) and 0.68 for the VRAG. For the RB justification for their decisions, the total HCR-20 yielded an average kappa coefficient of 0.76 (0.83 for the H factor, 0.73 for the C factor, and 0.67 for the R factor) and 0.72 for the VRAG.

Criminal Behaviour

Criminal History

Information on lifetime criminal convictions was obtained from the CPIC. Given that NCRMD verdicts are not recorded in CPIC records in a systematic fashion, we also coded NCRMD verdicts from RB files.

Index Offence

In many instances, an accused person had been charged with more than one offence leading to the index NCRMD verdict. All charges were coded, but only the most serious charge was selected as the index offence for the purpose of this study, ensuring consistency across provinces. Index offences were aggregated into 13 categories (Table 1) corresponding to the UCR2.32

Table 1.

Categories of offences

| Causing death or attempting to cause death |

| Sex offences |

| Assaults |

| Deprivation of freedom (for example, forcible confinement) |

| Threats, and other offences against the person |

| Property offences (for example, theft) |

| Prostitution and (or) gambling |

| Offensive weapons |

| Administration of justice (for example, failure to attend court and breach of probation) |

| Disturbing the peace |

| Drug possession and (or) trafficking |

| Dangerous driving and (or) operation of a motor vehicle |

| Other federal and (or) provincial statutes |

Categories 1 to 5 are offences against the person, category 6 are crimes against property, and the remaining categories fall under other Criminal Code violations.

Victims

For offences against the person, the relation between the accused and the victim was assigned to 1 of 6 categories (Table 2).

Table 2.

Categories of victims

| Stranger |

| Professionals (that is, police or security officer, mental health professional, and landlord) |

| Family (that is, offspring, parents, current and ex-partner or spouse, and other family members) |

| Roommate or co-resident |

| Friend and acquaintance |

| Other |

Severity of Offences

Descriptions of the offences were coded using the UCR2.32 A severity score was also assigned to each index offence using the Crime Severity Index, which is based on average sentence lengths.33

Recidivism

New charges and convictions were also coded from the CPIC records and the RB files. There is generally a significant time lapse owing to administrative delays between the date an offence is committed and the final verdict. This has important implications for our analysis of prior criminal offences and future criminality. For example, a verdict for offence X might occur after a verdict for offence Y, despite offence X actually being perpetrated before offence Y. Therefore, what may be identified as recidivism may be an artefact of delayed processing. Given that criminal records provide Court dispositions and do not provide offence dates, the following algorithm was applied to paint an accurate portrait of criminal history and recidivism: for each Court decision, we subtracted the median justice processing delay by province and matched for most severe offence; this is measured using the median time between the first and last hearing of a Court case.18

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the investigators’ primary institutions and renewed annually according to Tri-Council Guidelines.34,35

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal cohort study comparing provincially representative samples of NCRMD–accused people since the 1992 changes to the Criminal Code. It is clear there are differences across provinces in the likelihood of an NCRMD verdict; using data from Statistics Canada and the number of people found NCRMD, Quebec had 6.4 times the number of cases diverted to the RB system than Ontario, and 5 times that of British Columbia. British Columbia had 1.5 times the number of cases of Ontario when considering all criminal court decisions. Historically, Quebec courts have always yielded higher rates of NCRMD verdicts (or previously, Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity)36,37 and the gap appears to be increasing. As of 2012, the annual rate of NCRMD cases had increased in Quebec and stands at 9.27 per 1000 cases, it has stabilized in Ontario at 1.07 cases per 1000, and has decreased in British Columbia to 0.8 per 1000 criminal court cases.18 These differences may be due to differences in prosecutorial discretion, legal aid, and civil mental health resources and legislation, and Quebec may be using the NCRMD defence as a criminal justice diversion option.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has the advantage of a large sample, allowing us to examine interesting subgroups (for example, gender and diagnosis), low base rate characteristics, and recidivism rates. To our knowledge, the NTP is the first study to analyze detailed RB file content and the information on which RBs make their decisions. It also comprises one of the largest samples of people found NCRMD studied to date. The NTP entails a lengthy follow-up period and integrates official criminal records in addition to RB files to assess recidivism rates and predictors. Finally, this is also the only study to systematically examine provincial differences in the extent to which clinicians in forensic psychiatric practice have embedded evidence-based risk assessment measures into their clinical decision making.38

In terms of limitations, some information was not available in RB files in this archival study. This limited our ability to obtain details about symptoms at the time of the index offence, recovery while under the RBs, detailed diagnostic information, and violence risk assessments. In some cases, missing information could be interpreted as the absence of a factor. For example, one would not expect mention of someone’s non-Aboriginal status, thus no mention of Aboriginal status was coded as non-Aboriginal status. This results in a conservative estimate of missing data, as it is possible information was truly missing in some cases that were coded as factor absence. Variables with more than 10% missing data were dropped from multivariate analyses.39 Further, file data quality and quantity differed within and across provinces, over time and between RB hearings.

Conclusion

Given there are no current indications of increased criminality and court cases in Canada that could help explain the increased number of NCRMD cases over time,4 the profile of the NCRMD population is increasingly diversified. This increasing heterogeneity is evident regarding both criminal behaviour and clinical profile. The next 4 NTP papers, published in this special issue, examine the psychosocio-criminological profiles of NCRMD people, their processing across provinces, outcomes, as well as gender differences, in NCRMD profiles.40–43

Acknowledgments

This research was consecutively supported by grant #6356-2004 from Fonds de recherche Québec—Santé (FRQ-S) and by the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC). Dr Crocker received consecutive salary awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), FRQ-S, and a William Dawson Scholar award from McGill University while conducting this research. Dr Nicholls acknowledges the support of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the CIHR for consecutive salary awards. Yanick Charette acknowledges the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada in the form of a doctoral fellowship.

This study could not have been possible without the full collaboration of the Quebec, British Columbia, and Ontario Review Boards (RBs), and their respective registrars and chairs. We are especially grateful to attorney Mathieu Proulx, Bernd Walter, and Justice Douglas H Carruthers and Justice Richard Schneider, the Quebec, British Columbia, and consecutive Ontario RB chairs, respectively. We thank Carmelle Beaulieu from the Quebec RB for providing recent annual statistics. Ms Beaulieu has provided written permission to publish the information she sent to us at our request.

The authors sincerely thank Erika Jansman-Hart and Dr Cathy Wilson, Ontario and British Columbia coordinators, respectively, as well as our dedicated research assistants who coded RB files and Royal Canadian Mounted Police criminal records: Erika Braithwaite, Dominique Laferrière, Catherine Patenaude, Jean-François Morin, Florence Bonneau, Marlène David, Amanda Stevens, Stephanie Thai, Christian Richter, Duncan Greig, Nancy Monteiro, and Fiona Dyshniku.

Finally, the authors extend their appreciation to the members of the Mental Health and the Law Advisory Committee of the MHCC, in particular Justice Edward Ormston and Dr Patrick Baillie, consecutive chairs of the committee as well as the NTP advisory committee for their continued support, advice, and guidance throughout this study and the interpretation of results.

Abbreviations

- CPIC

Canadian Police Information Centre

- FPSC

Forensic Psychiatric Services Commission

- HCR-20

Historical-Clinical-Risk Management-20

- NCRMD

not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder

- NTP

National Trajectory Project

- RB

review board

- SMI

serious mental illness

- UCR2

Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (1988)

- VRAG

Violence Risk Appraisal Guide

References

- 1.Jansman-Hart EM, Seto MC, Crocker AG, et al. International trends in demand for forensic mental health services. Int J Forensic Ment Health. 2011;10:326–336. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priebe S, Badesconyi A, Fioritti A, et al. Reinstitutionalisation in mental health care: comparison of data on service provision from six European countries. BMJ. 2005;330:123–126. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38296.611215.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seto MC, Lalumière ML, Harris GT, et al. Demands on forensic mental health services in the province of Ontario. Toronto (ON): 2001. [publisher unknown]; Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latimer J, Lawrence A. The review board systems in Canada: overview of results from the Mentally Disordered Accused Data Collection Study. Ottawa (ON): Department of Justice Canada; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider RD, Forestell M, MacGarvie S. Statistical survey of provincial and territorial review boards. Ottawa (ON): Department of Justice Canada; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.1985. Criminal Code, R.S.C., c. C-46.

- 7.Tribunal Administratif du Québec. Rapport annuel de gestion 2006–2007 [Internet] Quebec (QC): Tribunal Administratif du Québec; 2008. [cited 2005 Jan 3]. Available from: http://www.taq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/publications-documentation/publications/depliants-guides-et-rapports2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ontario Review Board. Annual report, fiscal year: 2010–2011 [Internet] Toronto (ON): Ontario Review Board; 2011. [cited 2005 Jan 3]. Available from: http://www.orb.on.ca/scripts/en/annualreports.asp2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Livingston JD, Wilson D, Tien G, et al. A follow-up study of persons found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in British Columbia. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(6):408–415. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crocker AG, Nicholls TL, Seto MC, et al. The National Trajectory Project (NTP) [Internet] Montreal (QC): NTP; [year of publication unknown; cited 2015 Jan 1]. Available from: https://ntp-ptn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Canada. Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables. 2006 Census. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2007. Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, 2006 and 2001 censuses—100% data (table) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crocker AG, Braithwaite E, Nicholls TL, et al. To detain or to discharge? Predicting dispositions regarding individuals declared not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder. Oral presentation at the 10th Annual conference of the International Association of Forensic Mental Health Services; Vancouver, BC. 2010 May 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livingston JD. A statistical survey of Canadian forensic mental health inpatient programs. Health Q. 2006;9(2):56–61. doi: 10.12927/hcq..18104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Winko v British Columbia (Forensic Psychiatric Institute). 2 S.C.R. 6251999.

- 15.Balachandra K, Swaminath S, Litman LC. Impact of Winko on absolute discharges. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2004;32(2):173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desmarais S, Hucker S. Multi-site follow-up study of mentally disordered accused: an examination of individuals found not criminally responsible and unfit to stand trial. Ottawa (ON): Research and Statistics Divisions, Department of Justice Canada; 2005. p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider RD, Glancy GD, Bradford JM, et al. Canadian landmark case, Winko v. British Columbia: revisiting the conundrum of the mentally disordered accused. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2000;28(2):206–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics Canada. CANSIM Table 252-0055. Adult criminal courts, cases by median elapsed time in days, annual (number unless otherwise noted) [Internet] Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2013. Jun 12, [cited 2015 Jan 7]. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26;jsessionid=059C768E01E654D5F8C079EBE190D890?id=2520055&pattern=&p2=31&p1=1&tabMode=dataTable&stByVal=1&paSer=&csid=&retrLang=eng&lang=eng2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text rev. Washington (DC): APA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization (WHO) ICD-10 international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Geneva (CH): WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris GT, Rice ME, Quinsey VL. Violent recidivism of mentally disordered offenders. Crim Justice Behav. 1993;20(4):315–335. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webster CD, Douglas KS, Eaves D, et al. HCR-20: assessing risk for violence, version 2. Vancouver (BC): Mental Health Law and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grann M, Belfrage H, Tengström A. Actuarial assessment of risk for violence: predictive validity of the VRAG and the historical part of the HCR-20. Crim Justice Behav. 2000;27(1):97–114. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tengström A. Long-term predictive validity of historical factors in two risk assessment instruments in a group of violent offenders with schizophrenia. Nord J Psychiatry. 2001;55(4):243–249. doi: 10.1080/080394801681019093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroner DG, Mills JF. The accuracy of five risk appraisal instruments in predicting institutional misconduct and new convictions. Crim Just Behav. 2001;28(4):471–489. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas KS, Webster CD. The HCR-20 violence risk assessment scheme: concurrent validity in a sample of incarcerated offenders. Crim Just Behav. 1999;26(1):3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douglas KS, Reeves KA. Historical-Clinical-Risk Management-20 (HCR-20) Violence risk assessment scheme: rationale, application, and empirical overview. In: Otto RK, Douglas KS, editors. Handbook of violence risk assessment. New York (NY): Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2010. pp. 147–186. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Côté G, Hodgins S. Les troubles mentaux et le comportement criminel. In: Leblanc M, Ouimet M, Szabo D, editors. Traité de criminologie. 3ième ed. Montreal (QC): Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal; 2003. pp. 501–546. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinsey VL, Harris GT, Rice ME, et al. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quinsey VL, Harris GT, Rice ME, et al. Violent offenders: appraising and managing risk. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice ME, Harris GT, Hilton NZ. The Violence Risk Assessment Guide and Sex Offender Risk Appraisal Guide for violence risk assessment and the Ontario Domestic Assault Risk Assessment and Domestic Violence Risk Appraisal Guide for wife assault risk assessment. In: Otto RK, Douglas KS, editors. Handbook of violence risk assessment. New York (NY): Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics Policing Services Program. Uniform Crime Reporting Incident-Based Survey, reporting manual. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallace M, Turner J, Matarazzo A, et al. Measuring crime in Canada: introducing the Crime Severity Index and improvements to the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Tri-council policy statement: ethical conduct for research involving humans. Ottawa (ON): Interagency Secretariat on Research Ethics, Government of Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canadian Institutes of Health Research Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Social Sciences and Humanities. Tri-council policy statement: ethical conduct for research involving humans. Ottawa (ON): Research Council of Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodgins S, Webster CD. The Canadian database: patients held on lieutenant-governors’ warrants. Ottawa (ON): Research and Statistics Divisions, Department of Justice Canada; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodgins S, Webster CD, Paquet J. Canadian database: patients held on lieutenant-governors’ warrants. Ottawa (ON): Research and Statistics Divisions, Department of Justice Canada; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Côté G, Crocker AG, Nicholls TL, et al. Risk assessment instruments in clinical practice. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(4):238–244. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langkamp DL, Lehman A, Lemeshow S. Techniques for handling missing data in secondary analyses of large surveys. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(3):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crocker AG, Nicholls TL, Seto MC, et al. The National Trajectory Project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 2: the people behind the label. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(3):106–116. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crocker AG, Charette Y, Seto MC, et al. The National Trajectory Project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 3: trajectories and outcomes through the forensic system. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(3):117–126. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charette Y, Crocker AG, Seto MC, et al. The National Trajectory Project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 4: criminal recidivism. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(3):127–134. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicholls TL, Crocker AG, Seto MC, et al. The National Trajectory Project of individuals found not criminally responsible on account of mental disorder in Canada. Part 5: how essential are gender-specific forensic psychiatric services? Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(3):135–146. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]