Abstract

The 1997 Indonesian financial crisis resulted in severe economic dislocation and political upheaval, and the detrimental consequences for economic welfare, physical health, and child education have been established in several studies. The crisis also adversely impacted the psychological well-being of the Indonesian population. Comparing responses of the same individuals interviewed before and after the crisis, we document substantial increases in several different dimensions of psychological distress among male and female adults across the entire age distribution. In addition, the imprint of the crisis can be seen in the differential impacts of the crisis on low education groups, the rural landless, and residents in those provinces that were most affected by the crisis. Elevated levels of psychological distress persist even after indicators of economic well-being such as household consumption had returned to pre-crisis levels, suggesting the deleterious effects of the crisis on the psychological well-being of the Indonesian population may be longer lasting than the impacts on economic well-being.

I. Introduction

The 1997 Asian currency crisis, arguably one of the most disruptive global economic events in several decades, caused severe economic damage across much of East and Southeast Asia. No country was more affected than Indonesia. After several decades of sustained economic growth with low inflation, a stable exchange rate and three decades of President Suharto in power, the Indonesian society and economy were fractured by the 1997 crisis. The Indonesian Rupiah collapsed, falling from around Rp 2,500 per US$ in late 1997 to Rp 15,000 per US$ in mid 1998. GDP declined 12 percent in 1998 and the economy did not grow again until 2000. Prices spiraled up with inflation in 1998 reaching 80% while food prices increased by 160%. Economic upheaval was accompanied by political turmoil. President Suharto resigned after street protests in early 1998 which presaged historic changes in the system of national and local government. The vast majority of Indonesian households struggled to cope with both the immediate economic adversities they faced at the onset of the crisis as well as tremendous uncertainty over their economic, social, and political futures. Living through the stresses of the crisis potentially took a substantial toll on the psychological well-being of the population. This study examines the evidence and seeks to identify those subgroups of the Indonesian population who paid the highest price in terms of their psychological health.

The impacts of the crisis on economic well-being were far from uniform. By several measures, the crisis was centered in urban areas and disadvantaged urban households bore the brunt of the crisis (Frankenberg et al., 1999; Friedman and Levinsohn, 2002). Household consumption declines and increases in poverty rates were much greater in urban areas than in rural areas. For example, it is estimated that between 1997 and 1998, household per capita expenditure declined by 34% among those living in urban areas and by 13% among rural households (Frankenberg et al., 1999)1 Among rural males who were self-employed – mostly farmers – real hourly earnings declined by 11% but among those working in the market sector, real wages declined by more than 50% in one year. Rural wage earners are primarily landless laborers and government workers (whose wages were set in nominal terms prior to the onset of the crisis). In the urban sector, real hourly earnings of males declined by 50% in both the market and self-employed sectors. While hourly earnings collapsed, employment rates remained remarkably stable although there was some migration from urban to rural areas. (Smith, et al., 2002.) These facts are a reflection of the rise in the relative price of food, particularly rice, which benefited food producers, and the concomitant collapse of real wages which took its greatest toll on urban workers and the rural landless.

The economic impacts of the crisis also varied dramatically across the 27 Indonesian provinces and numerous island groups even within urban and rural areas (Levinsohn et al., 2003). More urbanized provinces in Java, such as Jakarta and West Java, suffered the largest contractions whereas the deleterious economic effects of the crisis were substantially more muted in those provinces that produced exports and export-related services such as tourism (in Bali, for example) and the production of oil, timber, and fishing (on Sumatra). Variation across provinces and between rural and urban areas was a fundamental aspect of Indonesia’s economic crisis and these patterns are important for understanding how the economic crisis affected psychological well-being.

A series of studies have described the effects of the crisis on multiple dimensions of the economic well-being and physical health of the Indonesian population. Taken together, those studies indicate a dramatic but short-lived decline in the economic well-being of most Indonesians suggesting an enormously resilient population that took great efforts to weather the storm.2 In sharp contrast, the impact of the financial crisis on psychological and mental health has not been explored to our knowledge. The goal of this paper is to provide empirical evidence on the extent to which the manifold upheavals and associated stresses of the Indonesian crisis affected the psychological health of the Indonesian population and whether any such effects were long-lasting. In so doing, we contribute new evidence on the psychosocial costs of economic insecurity in developing countries.

Das et al. (2008) review the limited population-level evidence of psycho-social disability in developing countries. Typically, the highest levels of psychological pathologies are found in countries emerging from conflict, where levels of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are high among the general population (Joop et al., 2001). Populations in regions that have suffered from natural disaster also suffer significantly more psychological distress in terms of depression, somatization, and anxiety (Wang et al., 2000; Frankenberg et al., 2008). Given this evidence, it is plausible to suppose that severe economic dislocation may have adverse effects on health in general and psychological health in particular. Tangcharoensathien et al. (2000) show that, after the onset of the financial crisis in Thailand, severe stress, suicidal ideation and hopeless feelings are more prevalent among unemployed, relative to employed people. However, in the absence of any information prior to the crisis, it is not known how much of these gaps are related to the crisis or what the impact of the crisis was on the psychological well-being of the general population. Before describing the evidence in Indonesia, where the crisis was both deeper and longer-lasting, we describe our data which is population-based and where we have interviewed the same people before and after the financial crisis.

II. Data

Using data from the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS), we track indicators of psychological distress of the same individuals who were assessed in up to three interviews over a period before, during and after the onset of the crisis. The IFLS is an on-going multi-purpose individual-, household- and community-level longitudinal survey. The first wave of IFLS was fielded in 1993 and collected information on over 30,000 individuals living in 7,200 households. The original sample covered 321 communities in 13 provinces and is representative of the population residing in those provinces, about 83% of the national population. (Outlying provinces were excluded from the sample for cost reasons.)

The same respondents were re-interviewed in 1997 (IFLS2), a few months before the beginning of Indonesia’s currency crisis, and again in 2000 (IFLS3). About one-quarter of the respondents were re-interviewed in 1998 (IFLS2+) in order to measure the immediate impacts of the crisis.3 Attrition is low in both resurveys.4

In addition to collecting extensive information on the socio-economic and demographic characteristics of respondents and their families, IFLS assesses the psychological well-being of its respondents using a common interview-based survey instrument of the type outlined in Das et al. (2008). The particular IFLS psychological health questions are adapted from the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) and attempt to measure symptoms of two globally common categories of psychiatric disorder – depression and anxiety (Goldberg, 1972). Appendix Table 1 presents the IFLS questions used in this study. They focus on general feelings of sadness or anxiety as well as specific symptoms of distress.5 These questions have been translated and back-translated to ensure accuracy, as well as extensively tested in the field in order to ensure comprehension among study subjects. Appendix Table 1 also includes a question on self-perceived general health status. This standard health survey question is a summary measure of health that encompasses physical and non-physical domains of well-being. In the subsequent analysis, general self-reported health status, as a broader summary of health, will provide a useful comparison with psychological health indicators and emphasize the potentially unique impacts of the crisis on psychological well-being.

Appendix Table 1.

IFLS psychological and general physical health status questions

| Indicators of Psychological distress | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| In the last four weeks, have you… | |||

| a. experienced sadness? | 1. often | 2. sometimes | 3. never |

| b. experienced anxiety or fear? | 1. often | 2. sometimes | 3. never |

| c. had a hard time sleeping? | 1. often | 2. sometimes | 3. never |

| d. felt fatigue or exhaustion?* | 1. often | 2. sometimes | 3. never |

| e. been short-tempered or hypersensitive?* | 1. often | 2. sometimes | 3. never |

| f. felt bodily pains?* | 1. often | 2. sometimes | 3. never |

| Indicator of general health status | ||

|---|---|---|

| In general, how is your health? | 1. very healthy | 2. somewhat healthy |

| 3. somewhat unhealthy | 4. very unhealthy | |

not asked in 2000

In terms of survey implementation, the psychological health questions were assessed in full in the 1993 and 1998 survey waves and a subset of the questions were assessed in the 2000 wave. (The subset is marked with an asterisk in Appendix Figure 1). Unfortunately, the psychological health questions were not included in the 1997 wave.

For much of the analysis, we exploit the panel nature of the data to contrast the general psychological health of each individual at two points in time, 1993 and 2000 (the 1998 results from the 25% sub-sample will also be used). This seven year period brackets the financial, political, and social crisis which, given its magnitude, is likely the dominant factor underlying changes in psychological health over this period. An important advantage of using 1993 for comparison is that our estimates will not be contaminated by the impact of expectations regarding an impending crisis.

III. Results

Psychological distress, pre- and post-crisis

We begin with an overview of our psychological well-being indicators before and after the onset of the 1997 crisis. Table 1 reports the overall prevalence of psychological distress in the population of adults age 20 and above at the time of each wave of the survey along with the percentage of respondents who state they were in poor general health status.6 The upper panel reports results for males and the lower panel for females. The left hand panel reports estimates that draw on reports from all respondents in each wave of the survey. The estimates are weighted so that they are representative of the underlying population.7

Table 1.

Prevalence of psychological distress and poor health

Percentage of male and female respondents aged 20 and older reporting health problems

| Males | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health indicator | All respondents | Panel respondents | |||

| 1993 | 1998 | 2000 | 1993 | 2000 | |

| Psychological health | |||||

| Sad | 12.0 | 28.9* | 27.5* | 11.4 | 24.2* |

| Anxious | 4.6 | 19.7* | 18.4* | 4.6 | 15.5* |

| Sad or anxious | 13.8 | 32.7* | 32.4* | 13.5 | 28.6* |

| Insomnia | 18.3 | 31.4* | 27.4* | 18.6 | 28.4* |

| Fatigue | 25.5 | 47.2* | -- | 25.2 | -- |

| Short temper | 11.8 | 28.7* | -- | 11.7 | -- |

| Somatic pain | 17.4 | 57.9* | -- | 17.0 | -- |

| General health status | |||||

| Poor general health | 10.7 | 11.4 | 11.6* | 9.7 | 15.1* |

| Sample size | 5,629 | 2,928 | 10,128 | 4,598 | 4,598 |

| Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health indicator | All respondents | Panel respondents | |||

| 1993 | 1998 | 2000 | 1993 | 2000 | |

| Psychological health | |||||

| Sad | 15.8 | 41.0* | 37.5* | 17.1 | 37.6* |

| Anxious | 7.3 | 25.9* | 24.4* | 8.5 | 23.6* |

| Sad or anxious | 17.9 | 44.1* | 42.7* | 19.9 | 42.2* |

| Insomnia | 22.3 | 35.0* | 32.6* | 23.6 | 35.9* |

| Fatigue | 26.3 | 54.0* | -- | 28.5 | -- |

| Short temper | 16.6 | 39.5* | -- | 18.1 | -- |

| Somatic pain | 20.1 | 62.0* | -- | 21.6 | -- |

| General health status | |||||

| Poor general health | 10.9 | 13.4* | 14.3* | 11.3 | 17.1* |

| Sample size | 6,892 | 3,222 | 11,271 | 5,957 | 5,957 |

Note: Prevalence estimates weighted to be population representative. Panel sample includes respondents aged at least 20 years in 1993 and interviewed in both 1993 and 2000. Asterisk (*) indicates column is significantly different from 1993 prevalence at 1% level.

Psychological distress indicators measured in IFLS are dramatically higher after the onset of the 1997 crisis. For both males and females, between 1993 and 1998, the prevalence of distress almost doubles for each indicator except one, difficulty sleeping, which increases by about 50%. To illustrate, in 1993 about 12% of men report feeling sad in the prior four weeks; in 1998, nearly 30% of men report feeling sad. Women are slightly more likely to feel sad than men are in 1993 (16%) and much more likely to feel sad in 1998 (41%). There were even larger proportionate increases in the prevalence of anxiety which rose three- to four-fold (from a lower base). Combining both markers into an index identifying those who report feeling either sad or anxious, about one in six respondents report such feelings in 1993. In 1998, one in three males and almost one of every two females report these feelings. In 1993, one in five respondents has difficulty sleeping and by 1998 this affects one in three adults. The prevalence of fatigue nearly doubles and short temper more than doubles. For both males and females, the prevalence of reported somatic pain triples from around 20% to 60% of respondents.

The increase in prevalence of psychological problems between 1993 and 1998 suggests a substantial rise in underlying psychological and emotional distress over this period which, as shown in the third column of the table, persists well beyond the onset of the crisis. There is only a small decline in the prevalence of psychological distress between 1998 and 2000 for both men and women. This persistence is noteworthy since by 2000 the Indonesian economy had begun to recover and mean household consumption levels had already returned to the pre-crisis levels of 1997 (Ravallion and Lokshin, 2007).

In contrast to the increase in psychological problems, self-reported general health status changes very little over the entire seven year period. Around 11% of males and between 11 and 14% of females report themselves as being in poor health. The relative stability of this general health measure suggests that the psychological distress indicators identify a change in a different dimension of health and well-being than general health and that the crisis differentially affected these separate dimensions.

The analyses thus far provide evidence on the prevalence of health problems in the population. It is useful to explore transitions in health over this period which requires following the same individual over time. The right hand panel of Table 1 reports the prevalence of psychological problems and poor general health among respondents who were individually assessed in both 1993 and 2000 and were age at least 20 in the 1993 baseline. Over 80% of the 1993 respondents were also interviewed in 2000. Comparing prevalence rates for the population (in the first column) with the rates for the panel sample at baseline (in the fourth column) provides insights into the representativeness of the panel sample. For both males and females, the prevalence rates in 1993 are very similar across the columns. The rates in 2000 are not directly comparable in the cross-section and panel samples because the respondents are seven years older in the latter. For the psychological indicators, the rates are still close in value. Thus the panel sample replicates the large increase in psychological distress between 1993 and 2000 that was observed in the cross-section sample. In contrast, in the panel sample, a larger fraction of respondents report themselves as being in poor general health relative to the cross-section sample. This is largely a reflection the fact that poor health rises with age and provides further evidence that time effects are minor relative to age effects in the case of general health status.

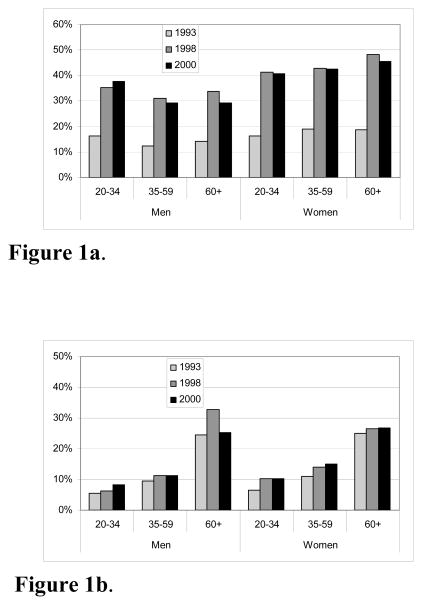

To explore the variation in psychological distress over the life course, Figure 1a provides a snapshot of the relationship between reported sadness or anxiety and age for males and females. The prevalence of sadness or anxiety varies little with age although prevalence rates are slightly higher among younger and older males in 1993 and among older females in all three years of observation. These modest age differences are dwarfed by the dramatic overall increase in prevalence between 1993 and either 1998 or 2000. At every age group, the prevalence of sadness or anxiety approximately doubles between 1993 and 1998 indicating a profound increase in psychological distress for adults across the entire age distribution. The estimates for 1998 and 2000 are roughly identical which indicates the persistence of crisis effects on psychological health across all ages, even as the Indonesian economy has begun to recover.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Incidence of sadness or anxiety in 1993, 1998, and 2000 by age and sex of respondent

Figure 1b. Incidence of poor general health in 1993, 1998, and 2000 by age and sex of respondent

These results in Figure 1a stand in contrast to those in Figure 1b, which present the same snapshot for general health status. A clearer age gradient is readily observed in Figure 1b – as respondents age they are more likely to report poor general health. This result, consistent with the broader empirical literature, highlights the different domains of well-being identified by GHS and by the psychological health questions. Another difference concerns the relative lack of change in the GHS measure over the 1993–2000 period. There does appear to be an increase in reported poor general health in 1998 in comparison to 1993, although one not close to the magnitude witnessed for the psychological distress measures. The general and sustained rise in the population’s psychological distress is not mirrored by changes in the population’s perceived general health.

Individual transitions in psychological distress and the crisis

Taking advantage of the longitudinal nature of IFLS, we investigate the rates at which individuals transition into and out of psychological distress. Table 2 summarizes the results for transitions between 1993 and 2000. For each measure of psychological distress, the percentage of people in each of four possible categories is listed – those who report psychological distress in both survey years, those who report no distress in either year, those who transition into distress, and those who transition out of distress.

Table 2.

Transitions in psychological well-being of panel respondents between 1993 and 2000

Percentage of respondents

|

All panel respondents (N = 10,524)

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instance of measure in year: | Psychological distress measure | Poor GHS [7] |

|||||

| 1993 [1] |

2000 [2] |

Sadness [3] |

Anxiety [4] |

Sad/anxious [5] |

Diff sleep [6] |

||

| No transition | |||||||

| No | No | 60.4 | 75.3 | 55.2 | 56.3 | 77.0 | |

| Yes | Yes | 6.8 | 2.2 | 8.6 | 10.3 | 3.7 | |

| Transition | |||||||

| No | Yes | 25.0 | 17.9 | 27.7 | 22.3 | 12.5 | |

| Yes | No | 7.9 | 4.6 | 8.5 | 11.1 | 6.9 | |

|

Male panel respondents (N = 4,586)

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instance of measure in year: | Psychological distress measure | Poor GHS | |||||

| 1993 | 2000 | Sadness | Anxiety | Sad/anxious | Diff sleep | ||

| No transition | |||||||

| No | No | 69.0 | 81.1 | 63.9 | 61.7 | 78.7 | |

| Yes | Yes | 4.6 | 1.2 | 6.0 | 8.6 | 3.5 | |

| Transition | |||||||

| No | Yes | 19.6 | 14.4 | 22.5 | 19.7 | 11.6 | |

| Yes | No | 6.9 | 3.4 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 6.2 | |

|

Female panel respondents (N = 5,938)

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instance of measure in year: | Psychological distress measure | Poor GHS | |||||

| 1993 | 2000 | Sadness | Anxiety | Sad/anxious | Diff sleep | ||

| No transition | |||||||

| No | No | 53.8 | 70.8 | 48.5 | 52.2 | 75.6 | |

| Yes | Yes | 8.4 | 2.9 | 10.6 | 11.6 | 3.9 | |

| Transition | |||||||

| No | Yes | 29.2 | 20.7 | 31.7 | 24.2 | 13.2 | |

| Yes | No | 8.6 | 5.6 | 9.3 | 11.9 | 7.3 | |

A substantial fraction of males and females transition into psychological distress during the observed period. However, over half the population – and in some cases three-quarters – experience no transition with the vast majority of these people never reporting they feel psychological distress. A small fraction of the population moves out of feeling distressed during this period. For example, among the 12% of males who feel sad in 1993, over half do not feel sad in 2000. Among the 17% of women who feel sad, half do not feel sad in 2000. At the same time, about 20% of males and 30% of females move from not feeling sad in 1993 to feeling sad in 2000. The patterns are broadly similar for the other indicators of psychological well-being.8 Females are more likely to transition into and out of distress. In general, the fraction of the population that transitions into psychological distress during this period is between 2 and 5 times greater than the fraction that transitions out of distress. In contrast with the psychological indicators, relatively few people transition into poor health while comparatively more transition out – two-thirds of those who are in poor health in 1993 report they are not in poor health in 2000, again underscoring a difference in this measure with the others in the table.

Psychological distress and individual characteristics

The combination of measures of psychological well-being along with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of individuals collected in IFLS provides unique opportunities to identify those sub-groups of the population who are at elevated risk of suffering from psychological distress during times of economic and political uncertainty. We use multivariate regression to identify susceptible groups before and after the onset of the crisis as well as those groups who are in psychological distress in both waves of the survey and those who are likely to transition into or out of psychological distress.

Individual characteristics include gender, age, and education – all of which are measured in 1993. Not all changes between 1993 and 2000 can be attributed to the 1997 crisis. We exploit the fact that the impact of the 1997 crisis differed dramatically across the Indonesian archipelago and relate differences in responses to the crisis to markers of the magnitude of the crisis for the area in which each respondent was living in 1993. Specifically, we distinguish not only province of residence but also those living in urban and rural areas and, among individuals in rural areas, we further distinguish respondents living in households that owned farm businesses from those that did not. The latter include landless laborers who relied on wage work as well as government workers such as teachers, public health workers and local administrators most of whose wages were set in nominal terms prior to the onset of the crisis and severe inflation. As noted above, because food prices rose faster than other prices, farmers were partially protected from the deleterious impact of the crisis whereas rural wage-earners and urban dwellers saw massive cuts in their real hourly earnings. Under the plausible assumption that the crisis was unanticipated in 1993, the impact of location of residence in 1993 on psychological distress can be interpreted as capturing impacts unaffected by behavioral responses to the crisis.

Regression results are reported in Table 3 for three indicators of psychological distress – sadness, anxiety, and difficulty sleeping – and also for poor general health using the sample of respondents who were age 20 in 1993 and interviewed in both 1993 and 2000. Columns 1 and 2 in each block examine the correlates associated with psychological distress or poor health in 1993 and 2000, respectively. We report odds ratios from logistic regressions with the dependent variable being unity if the respondent reports being in poor psychological or physical health. Columns 3, 4 and 5 in each block report the results of a transition model across the 1993 – 2000 which are estimated by multinomial logistic regression. We report risk ratios relative to not being in poor psychological or general health in both 1993 and 2000. Asymptotic t statistics are based on estimated standard errors that are robust to heteroskedasticity of arbitrary form and take into account correlations of unobserved factors that are common within households. The table presents results for gender, age, education, and rural/urban location. Differences by province will be summarized in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Demographic and socio-economic influences of psychological distress and general health, cross-sectional and panel estimates. Sample includes all male and female panel respondents age 20 and above in 1993

| Sadness | Anxiety | Sleep difficulties | Poor general health | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Select demographic/ socio-economic measures in 1993 |

Cross-section association |

Transitions across the two periods |

Cross-section association |

Transitions across the two periods |

Cross-section association |

Transitions across the two periods |

Cross-section association |

Transitions across the two periods |

|||||||||||||

| 1993 [1] |

2000 [2] |

Enter [3] |

Exit [4] |

Persist [5] |

1993 [1] |

2000 [2] |

Enter [3] |

Exit [4] |

Persist [5] |

1993 [1] |

2000 [2] |

Enter [3] |

Exit [4] |

Persist [5] |

1993 [1] |

2000 [2] |

Enter [3] |

Exit [4] |

Persist [5] |

||

| Male | 1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

|

| Female | 1.57 [8.04] |

1.89 [14.95] |

1.91 [13.71] |

1.59 [6.21] |

2.38 [10.18] |

1.95 [7.88] |

1.67 [10.11] |

1.63 [9.23] |

1.89 [6.30] |

2.85 [6.69] |

1.36 [6.41] |

1.45 [8.76] |

1.48 [7.94] |

1.41 [5.23] |

1.67 [7.41] |

1.21 [2.94] |

1.22 [3.57] |

1.25 [3.66] |

1.28 [3.07] |

1.21 [1.82] |

|

| 20–34 years | 1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

|

| 35–59 years | 1.08 [1.25] |

1.12 [2.29] |

1.11 [1.95] |

1.07 [0.74] |

1.19 [1.90] |

0.86 [1.75] |

1.00 [0.03] |

1.00 [0.03] |

0.84 [1.65] |

0.90 [0.74] |

1.21 [3.41] |

1.35 [6.09] |

1.31 [4.72] |

1.13 [1.67] |

1.56 [5.46] |

1.78 [6.97] |

1.77 [8.44] |

1.65 [6.73] |

1.59 [4.86] |

3.00 [7.03] |

|

| 60 years and above | 1.09 [0.91] |

1.38 [4.22] |

1.41 [4.04] |

1.12 [0.83] |

1.37 [2.23] |

0.79 [1.55] |

1.23 [2.34] |

1.23 [2.25] |

0.75 [1.54] |

1.02 [0.06] |

1.37 [3.71] |

1.88 [8.50] |

1.79 [6.83] |

1.20 [1.53] |

2.30 [7.19] |

3.96 [13.18] |

3.98 [15.26] |

3.76 [12.82] |

3.66 [10.05] |

9.66 [13.01] |

|

| Less than primary | 1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

|

| Primary graduate | 0.89 [1.74] |

0.87 [2.71] |

0.86 [2.63] |

0.86 [1.66] |

0.83 [1.93] |

1.06 [0.64] |

0.90 [1.83] |

0.88 [2.07] |

1.02 [0.14] |

1.08 [0.48] |

1.01 [0.08] |

0.95 [0.94] |

0.94 [1.10] |

0.99 [0.16] |

0.98 [0.24] |

0.79 [2.98] |

0.90 [1.56] |

0.95 [0.70] |

0.84 [1.93] |

0.70 [2.79] |

|

| Secondary graduate | 0.82 [1.99] |

0.82 [2.72] |

0.80 [2.73] |

0.77 [2.04] |

0.76 [1.94] |

1.49 [3.35] |

0.80 [2.58] |

0.79 [2.57] |

1.55 [3.11] |

1.17 [0.73] |

0.79 [2.76] |

0.72 [4.56] |

0.70 [4.15] |

0.78 [2.35] |

0.65 [3.48] |

0.53 [5.02] |

0.61 [4.88] |

0.71 [3.21] |

0.66 [2.98] |

0.23 [5.26] |

|

| Rural landed | 1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

1.00 -- |

|

| Rural landless | 1.04 [0.41] |

1.19 [2.60] |

1.19 [2.36] |

1.02 [0.12] |

1.20 [1.45] |

0.97 [0.25] |

1.18 [2.16] |

1.16 [1.84] |

0.86 [0.87] |

1.32 [1.19] |

1.08 [1.04] |

1.05 [0.68] |

1.09 [1.09] |

1.17 [1.59] |

1.05 [0.42] |

1.06 [0.54] |

1.13 [1.44] |

1.12 [1.18] |

1.01 [0.09] |

1.22 [1.23] |

|

| Urban | 1.34 [4.02] |

1.14 [2.31] |

1.13 [1.92] |

1.36 [3.31] |

1.43 [3.49] |

1.48 [3.86] |

1.12 [1.75] |

1.09 [1.37] |

1.44 [3.12] |

1.66 [2.79] |

1.17 [2.47] |

1.08 [1.48] |

1.09 [1.34] |

1.20 [2.28] |

1.19 [2.04] |

1.03 [0.37] |

1.03 [0.39] |

1.02 [0.27] |

1.03 [0.26] |

1.06 [0.42] |

|

Note: Odds ratios reported for logistic regression results in columns [1] and [2]. Dependent variable is 1 if respondent reports condtion, 0 otherwise. Relative risk ratios for multinomial logistic regression estimates in [3] to [5]. Excluded category is not reporting condition in either period. Entrants report condition in 2000 but not in 1993, exits report condition in 1993 but not in 2000, and and persisters report condition in borth periods. Excluded categories are male, age 20–34 years, less than completed primary school, and rural landed. Other controls include province of residence. Asymptotic t-statistics in brackets are robust to heteroskedasticity and take into account within-household correlations. Sample size is 10,555 respondents.

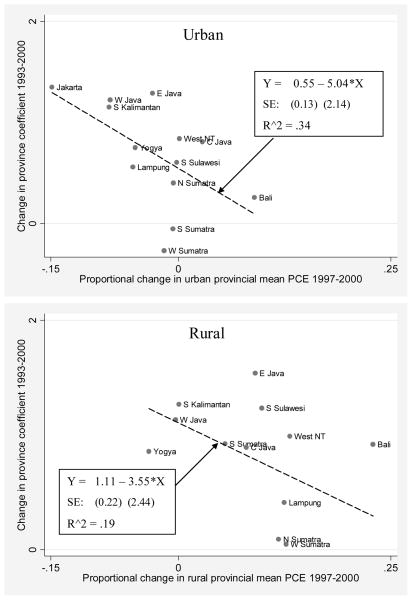

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of change in province conditional prevalence of sadness or anxiety, 1993–2000, and change in province mean per capita expenditure, 1997–2000, with fitted regression line

Gender plays an important role in both the prevalence of psychological distress and transitions across states of distress over time. In both 1993 and 2000, females are significantly more likely than males to report feeling sad, anxious, suffering from sleep difficulties, and being in poor general health, after controlling other characteristics. Relative to males, there is more churning among females and they are more significantly likely to transition between states of poor psychological or general health (in either direction). These transition rates are not large enough to offset the higher risks of being in poor health among females and so, relative to males, females are also more likely to be in poor health in both waves.

For example, females are 57% more likely than men to be sad in 1993; this gap increases to an 89% higher probability in 2000. This is reflected in the transition rates, reported in columns 3–4, which indicate that, relative to males, females are 95% more likely to become sad but 59% more likely to leave the sad state. Hence the larger gender gap in 2000. In contrast, the gender gap in risk of feeling anxious declines between 1993 and 2000 from 95% to 67%; relative to men, females are 89% more likely to exit the anxious state and 63% more likely to become anxious. Clearly there is more mobility into and out of psychological distress among women than men although, as column 5 indicates, women remain much more likely than men to be in sad or anxious in both waves.

Age is specified as a categorical variable with three groups, those aged 20–34, 35–59, and 60 years or greater (the youngest age group is the excluded category in Table 3). The influence of age varies with the particular psychological distress indicator. For example, feelings of sadness appear unrelated to age, conditional on other observed characteristics, in 1993. However by 2000, a clear age gradient emerges with those respondents in the oldest category 38% more likely to report sadness than the youngest category. This is largely because the likelihood of transitioning from not being sad to being sad is significantly higher for those aged 60 and over, as well as those in the middle age range. A similar patterns holds for feelings of anxiety – no clear age gradient in 1993 yields to a significantly positive gradient in 2000 where the oldest group is 23% more likely to report anxious feelings (and more likely to transition into feelings of anxiety). These general results echo the information in Figure 1a, where there is little evidence that age is associated with the risk of being sad or anxious before the onset of the crisis, however an age gradient does appear, at least for women, by 2000. In terms of the other well-being measures, both sleep difficulties and poor general health status tend to increase with age and older adults are more likely to transition into suffering from sleep difficulties or poor health as expected.

Education, which is an indicator of socio-economic status, is also measured as a categorical variable. Here respondents are grouped into 3 categories: those who have not completed primary school (including those with no formal education), primary school graduates (including those with some years of secondary schooling), and secondary graduates or higher. Education appears to have a slight negative relation to feelings of sadness in 1993 with secondary graduates 18% less likely to report sadness relative to the excluded category of those who have not finished primary schooling. This gradient is largely unchanged in 2000, although it becomes more precise with even primary graduates in 2000 13% less likely to report sadness than the excluded category..

Feelings of anxiety follow a different pattern. In 1993, there is a significant positive gradient between education and anxiety with those in the highest education category 49% more likely to report anxiety than the excluded category. In contrast in 2000 we observe a significant negative gradient where secondary graduates are 20% less likely to report anxiety than those without primary. Over the crisis period, those who have not attained primary school are significantly more likely to transition into anxiety while, conversely, secondary graduates or greater are significantly more likely to transition out of anxiety. Thus the crisis period witnessed a disproportionate increase in anxiety among the less educated. Studies cited earlier suggest the most vulnerable groups during the 1997 crisis were the poorer and less educated groups. This is reflected in our evidence for anxiety which likely most closely reflects concerns about economic insecurity.

The pattern for sleep difficulties and poor general health are relatively similar to each other. The better educated are less likely to have difficulty sleeping both before and after the onset of the crisis and they are less likely to experience a transition into or out of sleeping difficulties. The better educated tend to report better general health in 1993 and 2000 and they are also less likely to experience a transition into or out of poor general health.

The last three rows of Table 3 investigate the relationship between psychological health and area of residence, as well as landed status, prior to the onset of the crisis. Rural dwellers who owned land in 1993 are the reference category. They are, on average, the group that is most protected from the deleterious impact of the crisis because they tend to be food producers and the relative price of foods rose dramatically during the crisis. Within the rural sector, the landless are substantially more vulnerable to the negative impact of the crisis since they rely on (mostly non-farm) wage labor during a time when wages collapsed.

This difference in crisis vulnerability is apparent in the increasing relative likelihood of sadness and anxiety for the rural landless. Before the crisis, the rural landless were neither more nor less likely to report feelings of sadness or anxiety than the rural landed. Post-crisis, the landless were significantly more likely to be sad (19% more likely) or anxious (18% more likely) and significantly more likely to transition into sadness or anxiety. The buffer of land assets most likely helped to protect landed households from severe income shocks and increased psychological distress.9

Urban residents have a consistently higher likelihood to report sadness, anxiety, or sleep difficulties than landed rural residents before the crisis, and this remains true for feelings of sadness after the crisis as well (for both anxiety and sleep difficulties in 2000 urban residents still have a higher likelihood of distress, although the difference does not meet standard levels of significance). Urban residents are also more likely to transition across states of psychological distress and non-distress, and to remain in a state of psychological distress, than their rural counterparts. In contrast to the results with psychological health, urban location does not influence the self-report of poor general health (nor, for that matter, does rural landless status).

Clearly, urban status influences psychological distress indicators and constitutes an important conditioning variable however the relative importance of urban residence in determining psychological health does not change over the crisis period, at least in relation to landed rural households. If urban areas were more adversely affected by the crisis than rural areas, this impact does not translate into relatively higher psychological distress conditional on other observables. This is in part due to our separation of the rural population into landed and landless, where the results in Table 3 suggest that the rural landless bore the heaviest psychological burden of the crisis, as well as the fact that overall psychological distress was lower in rural areas in 1993. It is also possible that a high degree of heterogeneity in crisis impacts across Indonesia’s cities may mask any such crisis effect in the regression framework. Regional differences in crisis impact and their relation to changes in psychological distress are investigated in the next subsection.10

Regional variations in psychological health transitions

Besides education or rural landlessness, provincial location is another variable that mediated the severity of crisis exposure. The previously cited studies note large geographic variations in crisis indicators such as inflation or declines in real household resources. This highlights the important role of location within Indonesia in assessing the impact of the crisis on well-being. For example provinces on the island of Java were among the most affected while Bali, due to it’s reliance on tourism, and certain provinces in Sumatra and in the east of Indonesia, due to the importance of resource-intensive export industries, were comparatively less affected.

The spatial pattern in the changes in psychological distress indicators largely reflects these geographic differences in crisis severity. The models reported in Table 3 include controls for province of residence in 1993 (results not shown). As expected given the previous discussion, there are pronounced differences in the psychological distress indicators by province of residence. This is the case even after controlling for gender, age, education, and urban/rural location. In order to provide a context for interpreting the differences in estimated risk ratios for provinces, we relate those differences to a common measure of the impact of the financial crisis – the proportional change in mean real per capita household expenditure (PCE) observed for each provincial urban/rural cell.

These results are graphically summarized in Figure 2 which relates the change in the estimated province effect between 1993 and 2000 to the proportional change in regional PCE between 1997 and 2000. The change in the estimated province effect can be interpreted as the change in mean psychological distress in that province, conditional on population observables. The province effects are based on logistic regressions of the form reported in Table 3 except here they are estimated separately for urban and rural households. The measure of psychological distress is the combined measure of sadness and anxiety.11

The results show a similar pattern for rural and urban areas although the relationship is more pronounced in urban areas. Moving from left to right on either x-axis in Figure 2 indicates greater growth in PCE and, therefore, a more mild impact of the crisis. Almost all urban areas experience negative growth in PCE between 1997 and 2000. For example Jakarta experiences a 15% decline in PCE while PCE increases only for urban Central Java and urban Bali. PCE growth iss generally greater in rural areas, only three provinces – Yogyakarta, West Java, and South Kalimantan – experience a decline in PCE. Moving from bottom to top on either y-axis indicates an increase in the conditional provincial mean of sadness or anxiety from 1993 to 2000.

Even at this aggregate level, there is a clear positive relationship between crisis severity and change in the relative prevalence of psychological distress. The urban areas that experience the largest declines in mean income also exhibit the largest rise in relative prevalence of sadness or anxiety. At the other end of the spectrum, Bali fares relatively well over the crisis period and also posts one of the smallest increases in overall prevalence. This general relationship between crisis severity and change in prevalence is also apparent in the fitted regression line which has a significant negative slope (in spite of the small sample size of 13) and an R2 statistic of 0.34. While the crisis affects the psychological health of many urban Indonesians, those that live in cities most affected by crisis experiences the greatest increases in distress. 12

Rural residents in areas most affected by crisis also experience the greatest increases in psychological distress although the relationship is not as pronounced as that for urban residents, even after we exclude the outlier of rural Bali (where relative distress increases a good deal even though mean household incomes increased by almost 25%). The rural areas that experience negative or zero mean income growth over the 1997–2000 period witness some of the largest increases in psychological distress. In contrast North and West Sumatra, which experience healthy growth in PCE, also experience the smallest increases in distress. The overall relation between PCE growth and psychological distress is slightly weaker in the rural areas than urban; indeed the slope of the rural fitted regression line is distinctly negative by not significant at conventional levels. This weaker relation may in part be due to the fact that population in rural areas in total did not fare as poorly over the crisis period for the reasons discussed earlier.

IV. Conclusions

The 1997 financial crisis was the most disruptive socio-economic event to confront Indonesians for at least three decades. The effects of the crisis were wide ranging. While some households prospered given the new opportunities afforded by rapid price changes, shifts in the structure of the economy, and the political landscape, overall poverty increased and mean incomes fell. This study is the first to look at the Indonesian crisis impacts on psychological health and it does so using a high quality longitudinal socio-economic survey. We find that the severe economic dislocation and political uncertainty engendered by the crisis adversely impacted psychological health in the overall population.

We document substantial increases in distress indicators at all ages and for either gender over the crisis period. In addition, the imprint of the crisis on psychological well-being can be seen in the relatively large increase in poor psychological health for those groups most adversely affected: the less educated, the rural landless, and residents in cities hit hardest by crisis. Our analysis has focused on characteristics such as age, gender, education, and location prior to the crisis in order to avoid the complications that arise from the co-determinacy between psychological health and economic outcomes such as labor force participation or income. Hence we do not attempt to estimate and interpret correlations with characteristics that might respond to the crisis.

An additional important observation that emerges from this research concerns the persistence of psychological distress from the immediate post-crisis period in 1998 to the recovery period in 2000. By 2000 mean national household consumption has already recovered to 1997 levels and the overall economy returned to pre-crisis growth rates, however psychological distress remains at elevated levels. The result that psychological distress persists even after income and consumption have recovered suggests that economic dislocation has longer-lasting effects on psychological well-being than on economic status. Of course, it is too early to tell what the long-term effects of the shock will be with the current data ending in 2000, two years after the crisis; those issues will be addressed with the next wave of IFLS, collected in 2007/2008. Nonetheless, the evidence presented here suggests that psychological well-being does not go hand in hand with standard measures of welfare based on economic status and that a more complete picture of the consequences of the economic crisis is provided by also examining the impact on psychological health..

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NICHD grant HD040245.

Footnotes

Poverty rates more than doubled in urban areas while rising about 50% in rural areas (Suryahadi et al. 2003).

Studies have described the impact of the crisis on of poverty, consumption and wealth, labor supply, wages and earnings, schooling, physical health and health care utilization (Frankenberg et al. 1999; Suryahadi et al. 2003; Frankenberg et al. 2003; Thomas et al. 2004; Strauss et al., 2004).

The sample for the 1998 wave comprised 25% of the IFLS enumeration areas which were purposively selected to span the socio-economic and demographic diversity of the country. The 1998 sample achieves over 80% efficiency relative to the entire IFLS sample.

Considerable attention has been placed on minimizing attrition in IFLS. In each re-survey, about 95% of households have been re-contacted, thus minimizing data concerns that can arise from selective attrition. Around 10–15% of households moved from the location in which they were interviewed in the previous wave and concerted effort was made to track these households to their new location. In addition, individuals who moved out of their original IFLS household have been followed. This has added around 1,000 households to the sample in 1997 and about 3,000 households in 2000.

The questions ask about a broad array of symptoms and although validation studies with the US based GHQ have concluded that if a clustering of symptoms within an individual is identified, psychiatrists are likely to make a diagnosis, the IFLS data do not provide diagnostic information and we interpret out measures as indicative of general psychological well-being in the population.

For ease of exposition, we have dichotomized the psychological distress and general health status questions. We combine respondents that report the experience of a particular psychological distress indicator either often or sometimes over the past four weeks. Likewise if a respondent reported their general health status as ‘somewhat unhealthy’ or ‘very unhealthy’ we recode to being in ‘poor general health’. An alternative approach to measurement of health problems with survey data is to aggregate responses to several questions and create a summary index (see Das et al. (2007) for an example in psychological health). We present results for two domains of psychological problems – feeling sad or anxious – and suffering from sleep difficulties. Those are the only questions that are repeated across all three survey waves. Our results are qualitatively unchanged if we combine all six questions into an index and compare 1993 with 1998 or if we combine the three common questions across the three surveys into an index and compare 1993 with 1998 and 2000.

The sample sizes vary across the waves due to the survey design. In 1993, a subsample of adults was interviewed in each household. In 1998 and 2000, all adults were individually interviewed. Recall the 1998 wave was restricted to a 25% sub-sample of enumeration areas.

The patterns are also similar for transitions in the 25% sub-sample over the 1993 – 1998 period. When looking at the 1998 – 2000 period, the relative persistence of distress in contrast to either the 1993 – 2000 or the 1993 – 1998 period is significantly more pronounced, indicating greater stability in the psychological measures over this shorter post-crisis period.

An alternative explanation for this finding may arise if landless rural respondents are more likely than landed respondents to migrate to urban areas, where psychological distress is higher in general. However when we condition the analysis on individuals who have never migrated, identical results are obtained.

The data affords more generous regression specifications that can include a broader set of socio-economic characteristics in the models such as marital status and religion of respondents, living arrangements, wealth and household resources as well as employment status. However it is not clear how one might interpret estimates from these models since these characteristics are potentially correlated with other, unobserved, factors that also influence psychological well-being. While marital status, work status and wealth accumulation have all been shown to be associated with psychological well-being, the direction of causality has not been established (Ettner et al., 1997; Dooley et al., 2000). We prefer to report a parsimonious specification under the assumption that the characteristics we include, educational attainment, location of residence, and ownership of land, are largely fixed before psychosocial well-being in 1993 is determined.

The conclusions are unchanged if we look at the prevalence of sadness or anxiety separately, or pool urban and rural households. Additionally, similar analysis that investigates the association of changes in GHS with provincial measures of crisis impact does not find any relationship, consistent with earlier results.

An alternative to the analysis described here is to regress individual changes in psychological health directly on the measured changes in mean provincial income. This approach finds similar results – respondents in provinces with larger contractions in mean income are significantly less likely to transition out of sadness or anxiety, given an initial state of psychological distress, then their counterparts in regions less affected by the crisis and hence these regions experience an increase in relative psychological distress.

Contributor Information

Jed Friedman, World Bank.

Duncan Thomas, Duke University.

References

- Das Jishnu, Do Quy Toan, Friedman Jed, McKenzie David. Policy Research Working Paper Series. The World Bank; 2008. Mental Health Patterns and Consequence: Results from Survey Data in Five Developing Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Das Jishnu, Toan Do Quy, Friedman Jed, McKenzie David, Scott Kinnon. Poverty and Mental Health in Developing Countries: Revisiting the Relationship. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;65(3):467–480. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley D, Prause J, Ham-Rowbottom KA. Underemployment and Depression: Longitudinal Relationships. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(4):421–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner Susan L, Frank Richard G, Kessler Ronald C. The Impact of Psychiatric Disorders on Labor Market Outcomes. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 1997;51(1):64–81. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg Elizabeth, Thomas Duncan, Beegle Kathleen. RAND Working Paper No. 99-04. Santa Monica, Calif: 1999. The Real Costs of Indonesia’s Economic Crisis: Preliminary Findings from the Indonesia Family Life Surveys. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg Elizabeth, Smith James P, Thomas Duncan. Economic Shocks, Wealth, and Welfare. Journal of Human Resources. 2003;38(2):280–321. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg Elizabeth, Friedman Jed, Gillespie Thomas, Ingwersen Nick, Pynoos Robert, Sikoki Bondan, Steinberg Alan, Sumantria Cecep, Suriastiini Wayan, Thomas Duncan. Mental Health in Sumatra after the Tsunami. American Journal of Public Health. 2008 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120915. forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Jed, Levinsohn James. The Distributional Impacts of Indonesia’s Financial Crisis on Household Welfare: A ‘Rapid Response’ Methodology. The World Bank Economic Review. 2002;16(3):397–423. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire. London: Oxford University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Joop TV, de Jong M, et al. Lifetime Events and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in 4 Postconflict Settings. JAMA. 2001;286(5):555–562. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinsohn James, Berry Steven, Friedman Jed. The Impacts of the Indonesian Economic Crisis: Price Changes and the Poor. In: Dooley Michael, Frankel Jeffrey A., editors. Managing Currency Crises in Emerging Markets. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2002. pp. 393–428. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion Martin, Lokshin Michael. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 2008. Lasting Local Impacts of an Economywide Crisis. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss John, Beegle Kathleen, Dwiyanto Agus, et al. Indonesian Living Standards Three Years after the Crisis: Evidence from the Indonesia Family Life Survey. RAND Press; 2002. Get full cite. [Google Scholar]

- Suryahdi Asep, Sumarto Sudarno, Pritchett Lant. The Evolution of Poverty During the Crisis in Indonesia, 1996–1999. Asian Economic Journal. 2003;17(3):221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien Viroj, et al. Health Impacts of Rapid Economic Changes in Thailand. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:789–807. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Duncan, Beegle Kathleen, Frankenberg Elizabeth, Sikoki Bondan, Strauss John, Teruel Graciela. Education in a Crisis. Journal of Development Economics. 2004;74(1):53–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Xiangdong, et al. Post-earthquake quality of life and psychological well-being: Longitudinal evaluation in a rural community sample in Northern China. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2000;54:427–433. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2000.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]