Abstract

Background

The objectives of this research were to compare a web-based curriculum to a traditional lecture format on medical students’ cultural competency attitudes using a standardized instrument and to examine the internal consistency of the standardized instrument.

Methods

In 2010, we randomized all 180 first-year medical students into a web-based (intervention group) or a lecture-based (control group) cultural competency training. The main outcome was the overall score on the Health Belief Attitudes Survey (HBAS)(1=lowest, 6=highest). We examined internal consistency with factor analysis.

Results

No differences were observed in the overall median scores between the intervention (median 5.2; 25th percentile [Q1] 4.9, 75th percentile [Q3] 5.5) and the control groups (5.3, Q1 4.9, Q3 5.6)(p=0.77). The internal consistency of the two main sub-components was good (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83) to acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha 0.69).

Conclusions

A web-based and a lecture-based cultural competency training strategies were associated with equally high positive attitudes among first-year medical students. Our findings warrant further evaluation of web-based cultural competency educational interventions.

Keywords: Clinical Clerkship/methods, cultural competence, medical education, educational intervention

BACKGROUND

Cultural competency 1 and cultural competency training are important components of education during medical school. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) recommends an integrated approach for such training.2 Ultimately, an effective cultural competency education allows students to avoid stereotyping and empathize with the cultural norms of patients. To guide medical schools, the AAMC developed the Tool for Assessing Cultural Competency Training (TACCT) to assess the cultural competency content of medical school curricula.2–5 The instrument, designed by an expert panel, provides a framework that assesses five domains of a cultural competence curriculum: (1) rationale, context, and definition; (2) key aspects of cultural competence; (3) understanding the impact of stereotyping on medical decision-making; (4) health disparities and factors influencing health; and (5) cross-cultural clinical skills. The TACCT domains are subdivided into specific objectives for student knowledge, attitudes, and skills.2 While the TACCT instrument provides a valuable assessment tool for cultural competency curricula, it was neither designed to evaluate nor suggest teaching strategies or assess learning outcomes.

Initiatives to integrate cultural competency training in medical school curricula have been implemented in various formats. In meta-analyses, cultural competency training has been shown to improve knowledge, attitudes, and skills among health care providers;6,7 both long and short interventions were successful. However, the meta-analyses also identified shortcomings in study methodology and the need for uniform assessment methods.6,7 Moreover, 2 of the 64 studies included in the meta-analyses used a randomized controlled design and most (n=50) were designed without a comparison group.6,7 An updated review also highlighted the limitations of cultural competency studies with no control groups and nonrandom assignments.8

Despite these limitations, research to date suggests that cultural competency training can effectively sensitize health care professionals to cultural differences. However, important barriers still exist for implementing cultural competency training in medical schools; examples include identifying the time in the curriculum and finding faculty with time to compile and present the information. In addition, assessment instruments have been only partially tested in other settings. Thus, testing the effectiveness of new, short, and standardized approaches for teaching cultural competence is warranted.

Given this framing, we first developed and tested an online web-based curriculum in a prior study – the Cultural Competence Online for Medical Practice (CCOMP).9 The main objectives of the present study were: a) to compare the online web-based curriculum to a traditional lecture format on medical students’ cultural competency attitudes using a standardized instrument; and, b) to examine the internal consistency of the standardized instrument internal consistency with factor analysis. A final objective was to compare the sub-scores of the standardized instrument between the two groups. Some but not all studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of web-based formats to improve knowledge, attitudes, and even clinical outcomes.10–14 However, we are not aware of a randomized controlled study comparing a web-based approach to other formats to teach cultural competency.

METHODS

Design, Setting, and Participants

In a randomized controlled study, all first year medical students (matriculating class of 2010) were randomized to a traditional lecture format (control group) or the online web-based curriculum (intervention group) in September of 2010. The school administration provided aggregated data on race and ethnicity; students identified themselves as white or Caucasian (n=134), Asian or Asian-Indian (n=23), black or African American (n=10), Hispanic (n=4), and nine provided no response. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the study. The study was conducted in the context of a required activity as part of the Introduction to Clinical Medicine curriculum. Participation in the study was reflected in completion of the survey following delivery course content. Students received no incentives or penalties.

Control Group

The lecture-based format consisted of a 33-slide presentation, presented in a single lecture, focusing on the importance of clear communication, overcoming language barriers and eliciting the patient’s perspective on his or her own illness. The lecture included the use of a video recording of a clinical interaction focusing on the impact of cultural issues on a patient outcome, and a large group discussion of these issues. The lecture, akin to a ‘usual care’ group in a clinical trial, was the same one delivered for the previous two years. The content of the lecture was different than the web-based activity. Attendance was required.

Intervention Group

The web-based training consisted of four highly interactive case-based modules emphasizing cross-cultural approaches to care for African-American patients with cardiovascular disease, especially hypertension. Students were required to complete all cases in an independent study fashion.

The web-based curriculum, Cultural Competence Online for Medical Practice (CCOMP), was designed and implemented after a rigorous formative evaluation process.9 Designed for practicing physicians, residents, and medical students, the website is available in the public domain (www.c-comp.org). Briefly, the site is organized in four areas: patient’s background, provider and health care, cross-culture, and resources to manage cultural diversity. As the formative evaluation indicated greater importance of the first two domains, the four case-based modules are embedded in the patient’s background and provider and health care areas. The cases include videos with portions of stories from real-life patients15 and interactive questions. After each question was answered, participants received immediate feedback of their responses as compared to the response by others participants. A correct answer was not the goal of the question; rather, feedback was provided in the form of comparison with the responses of others. We based this approach from the social cognitive approach of learning16 and peer-comparison from the quality improvement literature.14,17 Each case took approximately 5–15 minutes to complete. Table 1 shows a general overview and educational objectives for each case.

Table 1.

Online Training. Overview and Educational Objectives.

| Domain/Case/Main Objective | Description | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Patient’s Perspective | ||

| Case #1. Cultural Background. | ||

| To define race, ethnicity, and culture and identify patients’ cultural and social background | Highlights religion’s impact on patient reactions to diagnosis, coping mechanisms, and its importance in forming a therapeutic alliance | 3 stories from real patients (video, duration 30 sec to 1.5 min); 9 objectives; 3 patient interviews; 3 Likert-style multiple choice questions and 1 short answer question, including explanations; module summary |

| Case #2. Diet and Exercise. | ||

| To identify how race and culture relate to health, care-seeking behaviors-health beliefs, and adherence | Highlights the role of food in culture, barriers to diet changes and adherence and the importance of the DASH diet in African Americans | 4 stories from real patients (video, duration 1 min to 1.5 min); 10 objectives; 4 patient interviews; 3 Likert-style multiple choice questions and 1 short answer question, including explanations; module summary |

| About Providers | ||

| Case #3. Explore Stereotyping. | ||

| To identify physician stereotyping | Highlights the importance of eliciting a thorough patient history in order to recognize and avoid stereotyping in patients with cardiovascular disease | One interactive case-vignette (text); 15 objectives; 1 clinical scenario; 3 multiple choice questions, 3 Likert-style multiple choice questions and 1 short answer question, including explanations; module summary |

| Case #4. Explore Biases. | ||

| To identify physician bias, describe own bias, list how it affects clinical care, and demonstrate strategies to address/reduce physician bias | Highlights how even a subconscious bias may affect the care of patients with cardiovascular disease | One interactive case-vignette (text); 14 objectives; 1 clinical scenario; 1 multiple choice and 4 Likert-style multiple choice and 1 short answer question, including explanations; module summary |

Main Outcome

For the primary objective, the main outcome was the overall attitude score on the Health Beliefs Attitudes Survey (HBAS) – a standardized instrument to assess cultural competency attitudes.18,19 Students completed the HBAS within two weeks after completion of their respective cultural competency training. The HBAS consists of 15 items, scored on a 6-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=moderately disagree, 3= mildly disagree, 4=mildly agree, 5= moderately agree, 6= strongly agree; higher score indicates more culturally competent attitudes). The HBAS assesses various aspects of students’ attitudes on the relationship of cultural competency to quality healthcare and has been partially tested (excellent internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha 0.79 – 0.86; previously reported mean values of 4.4 – 5.4). The survey was not anonymous and was not graded.

Sample Size

The sample size for a difference in HBAS scores between groups of 0.5 and a SD of 0.6 to 0.8 was 30 to 54 per group (alpha 0.05, beta 0.20). Thus, the entire class of students (n=180) had enough power to detect differences in scores between groups of 0.3 (SD 0.6) to 0.5 (SD 1.0). We estimated the effect size from a prior before- and after- study of the lecture (unpublished observation).

Randomization

To maintain approximate equal sized groups, we used random variable block randomization (Pascal’s triangle; 1:4:6:4:1; STATA 11.2 software, College Station, Texas, USA). The allocation was not concealed or blinded. Each student received an electronic communication indicating the allocation.

Statistical Approach

For the primary objective, main outcome, we computed the overall HBAS score by calculating the mean of all 15 questions (Table 2).18,19 Following instructions from the original report, the scale was reversed for four questions (questions 3, 5, 7, 15; Table 2); the four questions were written in the negative to minimize social desirability. We used the intention-to-treat principle to compare medians between the intervention and control groups with the Mann-Whitney U test (data was not normally distributed).

Table 2.

Health Beliefs Attitudes Survey (HBAS). Factor Analysis.

| Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha if removed | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor #1. Importance of Understanding and Utilizing Patient Perspective (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83) | ||

| Role of Patient Perspectives and Opinions in Diagnosis | ||

| 1 Physicians should ask patients for their opinions about illnesses or problems. | 0.504 | 0.83 |

| 2 It is important to know the patients’ points of view for the purpose of diagnosis. | 0.519 | 0.84 |

| 6 Understanding patients’ opinions about their illnesses helps physicians provide better care. | 0.523 | 0.83 |

| Understanding Patient Beliefs: Using Clinical Skills to Eliminate Bias | ||

| 4 Understanding patients’ opinions about their illnesses helps physicians reach the correct diagnosis. | 0.618 | 0.83 |

| 8 Physicians should ask their patients what they believe is the cause of their problem/illness. | 0.615 | 0.83 |

| 10 Physicians can learn from their patients’ perspectives on their illnesses or problems. | 0.627 | 0.82 |

| 11 Physicians should ask their patients why they think their illness has occurred. | 0.750 | 0.82 |

| Context of the Illness: A Key Component of the Medical Interview | ||

| 9 A physician should learn about their patients’ cultural perspective. | 0.497 | 0.83 |

| 14 Physicians should ask patients for their feeling about their illnesses or problems. | 0.615 | 0.82 |

| Factor #2. Importance of Patient Perspective in Patient-Physician Relationship (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.69) | ||

| Building the Professional Relationship and Quality of Care | ||

| 3* Patients may lose confidence in the physician if the physician asks their opinion about their illness or problem. | 0.385 | 0.69 |

| 5* A physician can give excellent care without knowing patients’ opinions about their illnesses or problems. | 0.696 | 0.63 |

| 7* A physician can give excellent health care without knowing a patient’s understanding of his or her illness. | 0.664 | 0.64 |

| 15* Physicians do not need to ask about patients’ personal lives or relationships to provide good health care. | 0.502 | 0.66 |

| Determining Impact on the Patient’s Life and Expressing Empathy | ||

| 12 Physicians should ask about how an illness is impacting a patients’ life. | 0.473 | 0.67 |

| 13 Physicians should make empathetic statements about their patients’ illnesses or problems. | 0.427 | 0.67 |

Scale reversed for questions 3, 5, 7, and 15.

For the secondary objective, to examine the internal consistency of the standardized instrument, we performed factor analysis. We grouped the questions based on factors with Eigenvalues greater or equal than one and questions with rotated factors loading greater than 0.3 with each sub score having equal weights. We also explored a four factor solution as prior work has suggested four domains.19 We assessed internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha.

For the final objective, we compared the sub-scores of the standardized instrument (HBAS) between the two groups with the Mann-Whitney U test.

We used STATA 11.2 software (College Station, Texas, USA) for analyses and defined statistical significance at a p value <0.05.

RESULTS

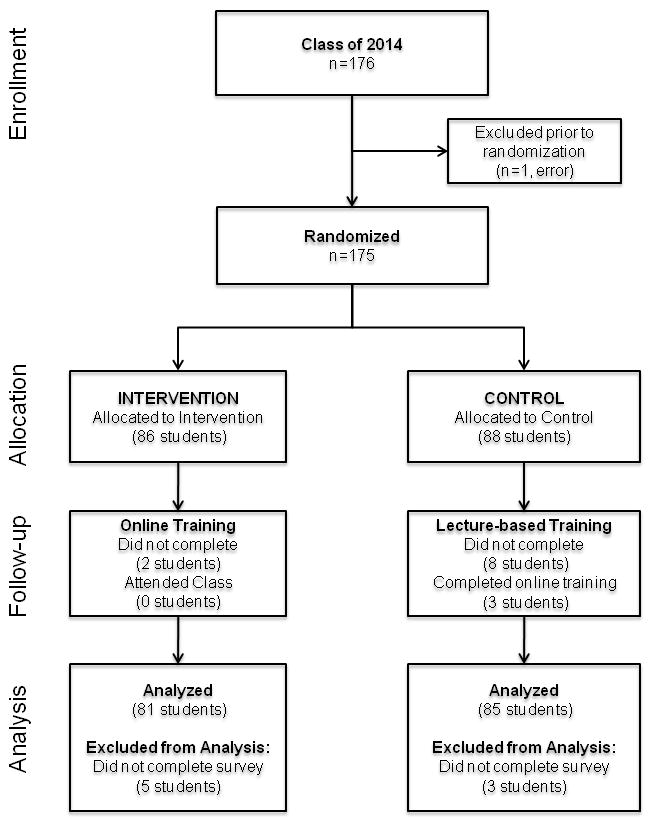

The matriculating class of 2010 consisted of 180 students (four did not complete registration), including 104 males and 76 females. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram of the participants is shown in Figure 1. Of the 176 students, one was not randomized in error, 86 were allocated to the intervention group and 88 were allocated to the control group. The randomization resulted in balanced gender distribution between groups (intervention, 44.2% females; control, 39.8% females; p= 0.56). Individual age and race data were not available. The HBAS survey was completed by 94.9% (166/175).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram

Main Outcome – Overall HBAS Scores

We did not observe differences in the overall median scores between the intervention (median 5.2; 25th percentile [Q1] 4.9, 75th percentile [Q3] 5.5) and the control groups (5.3, Q1 4.9, Q3 5.6)(p=0.77).

Internal Consistency - HBAS Instrument

The rotated factor loadings for each question organized by two factors are shown in Table 2. The two-factor solution explained 84.4% of the variance with Eigenvalues of 4.34 and 1.37 respectively. By reviewing the wording of the questions for the two factors, we conceptualize Factor #1 as the “Importance of understanding and utilizing patients’ perspective” and Factor #2 as the “Importance of patients’ perspective in the patient-physician relationship;” the Cronbach’s alpha (internal consistency) were 0.83 and 0.69, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha did not change by removing any of the questions (see Table 2, last column).

A four-factor solution 19 explained 107.9% of the variance with Eigenvalues of 4.34, 1.37, 0.92, and 0.70, respectively. The four-factor solution helped conceptualize sub-headings for the two-factor solution.

HBAS Sub-Components

We did not observe differences in the medians between the intervention and control groups for any of the sub-scores for either the two-factor solution (p=0.22, p=0.53) or the four-factor solution (p=0.22, p=0.42, p=0.50, p=0.24), see Table 3.

Table 3.

Health Beliefs Attitudes Survey (HBAS). Subcomponents scores between the Intervention (web-based) and Control (lecture-based) groups.

| Component | Questions | Intervention (n=80) | Control (n=83) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two Factors | ||||

| Factor #1 | 1, 2, 6 4, 8, 10, 11 9, 14 |

5.4 [5.0, 5.7] | 5.6 [5.0, 5.9] | 0.22 |

| Factor #2 | 3, 5, 7, 15 12, 13 |

5.0 [4.6, 5.5] | 5.0 [4.3, 5.5] | 0.53 |

| Four Factors | ||||

| Factor #1 | 4, 8, 10, 11 | 5.1 [4.5, 5.8] | 5.5 [4.8, 6.0] | 0.22 |

| Factor #2 | 9, 14, 12, 13 | 5.8 [5.4, 6.0] | 5.8 [5.5, 6.0] | 0.42 |

| Factor #3 | 3, 5, 7, 15 | 4.5 [4.1, 5.3] | 4.8 [3.8, 5.3] | 0.50 |

| Factor #4 | 1, 2, 6 | 5.7 [5.3, 6.0] | 5.7 [5.0, 6.0] | 0.24 |

Values are medians and 25th–75th percentiles [Q1, Q3]. HBAS Likert scale: 1=strongly disagree, 2=moderately disagree, 3= mildly disagree, 4=mildly agree, 5= moderately agree, 6= strongly agree; scale reversed for questions 3, 5, 7, and 15.

DISCUSSION

In a randomized controlled study, we found no differences between a web-based and a lecture-based cultural competency training approach on first year medical students’ attitudes, which were assessed using a standardized instrument (HBAS). Also, the HBAS internal consistency of the two main sub-components was good (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83) to acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha 0.69). Finally, we did not find differences among the sub-components of the instrument. Although we did not find differences in outcome between the groups, this study is novel in that it tested a short and standardized approach (web-based).

Since the web-based intervention is both short and standardized, it could be easily disseminated. The web-based cultural competency intervention does not require ongoing significant faculty time and lecture preparation. Of note, our study was not designed to test the independent contributions of content (material included) or delivery form between the groups (web-based vs. lecture format). After a standardized intervention early in medical education, students might have a strong framework for enriching cultural competency through more individualized but less reproducible experiences such as small group discussions and patient encounters.

In cultural competency training, a randomized design to test the effectiveness of interventions is rarely used. In one such study, Genao et al, conducted a randomized controlled trial among third year medical students to determine the effect of cultural competency training on student knowledge.20 The cultural competency group (n=62) used clinical vignettes and open discussion to cover seven main areas (health disparities, incidence and prevalence, stereotyping, exploring culture, perception of health and illness, communication and language, and gender issues). The control group (n=47) received lectures on other general medical topics. Genao et al found that knowledge scores improved by 19% in the intervention group as compared to 4% in the control group (p<0.01). However, the interventions evaluated in this study required intensive faculty time and are unlikely to be reproduced by other institutions or by the same institution from year to year.

For our main outcome, we acknowledge that others may have a different interpretation of the factors identified in the HBAS scale. In this study, we grouped items using factor analysis into two main factors, labeled as “Importance of understanding and utilizing patients’ perspective” and “Importance of patients’ perspective in the patient-physician relationship.” Other studies19 of the HBAS instrument defined four factors or domains: a) opinion: importance of assessing patients’ perspectives and opinions; b) belief: importance of determining patients’ beliefs for history taking and treatment; c) context: importance of assessing patients’ psychosocial and cultural contexts; and, d) quality: importance of knowing the patients’ perspective for providing good health care. In this study,19 the authors measured pretest and posttest attitudes among 91 medical students following completion of two cultural competency interventions (“Art of Medicine” and “History and Physical Exam” courses). Student pre vs. post mean sub-scores improved for opinion (4.88, 5.10; p=0.01) and belief (4.49, 5.08; p<0.001), but not for context or quality.19 In our study, we found similarly high scores.

We acknowledge limitations in our study. We used a single institution and explored a short-term outcome on attitudes. Student responses may have demonstrated a ceiling effect (high scores). However, with revision, the HBAS instrument could serve as an instrument to track student attitudes over time. Although contamination between the two groups may have occurred (and explain a no-difference between groups), this seems unlikely as medical students are immersed with other courses, basic science classes, and service activities. We did not measure attitudes before the study and students may have had different scores prior to this study. Finally, the study was not designed to assess skills, knowledge21 or patient outcomes.

In conclusion, in a randomized controlled-randomized study, we found no differences between web-based and lecture-based cultural competency training approach on first year medical students’ attitudes using a standardized instrument. Our findings warrant further evaluation of web-based cultural competency educational interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding and Support: This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K07 HL081373-01) to Dr. Estrada.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Other Disclosures: None

Disclaimer: The Department of Veterans Affairs Quality Scholars Fellowship (VAQS) is funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA). The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Contributor Information

Dr. Riley Carpenter, Email: riley.carpenter@phhs.org, Senior medical student at the University of Alabama School of Medicine, Birmingham, Alabama, USA, at the time the work was conducted and is now resident in Anesthesiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, USA.

Dr. Carlos A. Estrada, Email: cestrada@uab.edu, Director, Veterans Affairs Quality Scholars Program, Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and Professor of Medicine and Director, Division of General Internal Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Dr. Martha Medrano, Email: Dr.MMedrano@CommuniCareSA.org, Assistant Dean of Continuing Medical Education, as well as Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Assistant Professor of Family Practice and Psychiatry at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and Director of the Medical Hispanic Center of Excellence, San Antonio, TX, USA.

Ann Smith, Email: annsmith@uabmc.edu, Program Director in Preventive Medicine and the UAB Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Center, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Dr. F. Stanford Massie, Jr., Email: smassie@uab.edu, Professor of Medicine and director of the Introduction to Clinical Medicine course for first and second year medical students at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

References

- 1.Genao I, Bussey-Jones J, Brady D, Branch WT, Jr, Corbie-Smith G. Building the case for cultural competence. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326(3):136–140. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AAMC. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) [Accessed August 4, 2014];Using Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT) 2005 https://www.aamc.org/download/54336/data/usingtacct.pdf.

- 3.Lie D. Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT) [Accessed August 4, 2014];MedEdPORTAL. 2006 Available at: https://www.mededportal.org.

- 4.Lie D, Boker J, Cleveland E. Using the tool for assessing cultural competence training (TACCT) to measure faculty and medical student perceptions of cultural competence instruction in the first three years of the curriculum. Acad Med. 2006;81(6):557–564. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000225219.53325.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lie DA, Boker J, Crandall S, et al. Revising the Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT) for curriculum evaluation: Findings derived from seven US schools and expert consensus. Med Educ Online. 2008 Jan 1;13:1–11. doi: 10.3885/meo.2008.Res00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43(4):356–373. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156861.58905.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach MC, Cooper LA, Robinson KA, et al. Strategies for improving minority healthcare quality. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2004;90:1–8. doi: 10.1037/e439452005-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lie DA, Lee-Rey E, Gomez A, Bereknyei S, Braddock CH., 3rd Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Mar;26(3):317–325. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crenshaw K, Shewchuk RM, Qu H, et al. What should we include in a cultural competence curriculum? An emerging formative evaluation process to foster curriculum development. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):333–341. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182087314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fordis M, King JE, Ballantyne CM, et al. Comparison of the Instructional Efficacy of Internet-Based CME With Live Interactive CME Workshops: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2005;294(9):1043–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore DE, Jr, Pennington FC. Practice-based learning and improvement. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003 Spring;23 (Suppl 1):S73–80. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340230411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis N, Davis D, Bloch R. Continuing medical education: AMEE Education Guide No 35. Med Teach. 2008;30(7):652–666. doi: 10.1080/01421590802108323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Wall T, et al. Multicomponent Internet continuing medical education to promote chlamydia screening. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(3):285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Williams OD, Person SD, Weaver MT, Weissman NW. Improving quality improvement using achievable benchmarks for physician feedback: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285(22):2871–2879. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houston TK, Allison JJ, Sussman M, et al. Culturally appropriate storytelling to improve blood pressure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):77–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Grez L, Valcke M, Roozen I. The impact of an innovative instructional intervention on the acquisition of oral presentation skills in higher education. Computers & Education. 2009;53:112–120. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houston TK, Wall T, Allison JJ, et al. Implementing achievable benchmarks in preventive health: a controlled trial in residency education. Acad Med. 2006;81(7):608–616. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000232410.97399.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobbie AE, Medrano M, Tysinger J, Olney C. The BELIEF Instrument: a preclinical teaching tool to elicit patients’ health beliefs. Fam Med. 2003;35(5):316–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crosson JC, Deng WL, Brazeau C, Boyd L, Soto-Greene M. Evaluating the effect of cultural competency training on medical student attitudes. Family Medicine. 2004;36(3):199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genao I, Bussey-Jones J, St George DM, Corbie-Smith G. Empowering Students With Cultural Competence Knowledge: Randomized Controlled Trial of a Cultural Competence Curriculum for Third-Year Medical Students. J Nat Med Assoc. 2009;101(12):1241–1246. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31135-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bussey-Jones J, Genao I, George DMS, Corbie-Smith G. Knowledge of cultural competence among third-year medical students. J Nat Med Assoc. 2005;97(9):1272–1276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]