Abstract

Background

Mechanical ventilation (MV) is a life-saving measure for patients in respiratory failure. However, prolonged MV results in diaphragm weakness, which contributes to problems in weaning from the ventilator. Therefore, identifying the signaling pathways responsible for MV-induced diaphragm weakness is essential to developing effective countermeasures to combat this important problem. In this regard, the FOXO family of transcription factors is activated in the diaphragm during MV and FOXO-specific transcription can lead to enhanced proteolysis and muscle protein breakdown. Currently, the role that FOXO activation plays in the development of MV-induced diaphragm weakness remains unknown.

Objectives

This study tested the hypothesis that MV-induced increases in FOXO signaling contribute to ventilator-induced diaphragm weakness.

Interventions

Cause and effect was determined by inhibiting the activation of FOXO in the rat diaphragm through the use of a dominant negative FOXO (dnFOXO) adeno-associated virus vector delivered directly to the diaphragm.

Measurements and Main Results

Our results demonstrate that prolonged (12 hrs) MV results in a significant decrease in both diaphragm muscle fiber size and diaphragm specific force production. However, MV animals treated with dnFOXO showed a significant attenuation of both diaphragm atrophy and contractile dysfunction. In addition, inhibiting FOXO transcription attenuated the MV-induced activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, the autophagy/lysosomal system and caspase-3.

Conclusions

FOXO is necessary for the activation of key proteolytic systems essential for MV-induced diaphragm atrophy and contractile dysfunction. Collectively, these results suggest that targeting FOXO transcription could be a key therapeutic target to combat VIDD.

Keywords: respiratory muscles, transcription factor, FOXO, weaning, proteolysis, atrophy

Introduction

Mechanical ventilation (MV) is used clinically to provide sufficient alveolar ventilation in patients incapable of maintaining adequate pulmonary gas exchange. Although MV can be a life-saving intervention for patients with acute respiratory failure, prolonged MV results in the rapid development of ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction (VIDD), which occurs as a result of diaphragm atrophy and contractile dysfunction (1-3). From a clinical perspective, VIDD is important because respiratory muscle weakness is a contributing factor that can predict potential difficulties in weaning patients from the ventilator (4). Weaning difficulties are a dilemma in critical care medicine as 20-30% of mechanically ventilated patients experience weaning problems (5). Therefore, understanding the mechanism(s) leading to MV-induced diaphragm weakness is a critical step toward developing a therapeutic intervention to prevent VIDD.

The development of VIDD occurs rapidly as a result of decreased protein synthesis and increased proteolysis (6, 7). However, because of the rapid development of VIDD, MV-induced increases in diaphragm protein breakdown appear to play the dominant role (3). All four primary proteolytic systems are activated in the diaphragm during MV (i.e. calpain, caspase-3, ubiquitin-proteasome system and the autophagy/lysosomal system) (8-10). However, the trigger signaling the activation of each of these pathways during atrophy conditions remains unknown. In this regard, the forkhead boxO (FOXO) family of transcriptions factors are activated in the diaphragm during MV and appear to control skeletal muscle mass through the regulation of muscle atrophy-related genes (i.e. MuRF1, Atrogin-1/MaFbx, LC3 and BNIP3). Recent evidence suggests that prolonged MV activates the FOXO family of transcription factors in the diaphragm. Specifically, studies in both humans and animals report that prolonged MV results in an upregulation of FOXO signaling (e.g. FOXO1 and FOXO3) in the diaphragm (8, 11, 12). However, whether FOXO activation is required for the development of VIDD remains unknown.

Therefore, this study tested the hypothesis that MV-induced increased FOXO transcription in the diaphragm is a requirement for the development of VIDD. Cause and effect was determined by delivering a dominant negative FOXO (dnFOXO) adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector directly into the diaphragm to inhibit FOXO-specific transcription to elucidate the role that increased FOXO activity plays in the development of VIDD.

Methods

Animals and Experimental Design

Young adult (∼6 month old) female Sprague-Dawley rats were randomly assigned to the following groups (n = 8/group): 1) acutely anesthetized control with GFP; 2) acutely anesthetized control with dnFOXO-GFP; 3) 12 hours of MV with GFP; and 4) 12 hours of MV with dnFOXO-GFP. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Florida approved these experiments.

Packaging and Purification of Recombinant AAV Vectors

The dnFOXO plasmid was a gift of Dr. Andrew Judge (University of Florida, Gainesville) and has been previously described (13). Specifically, the dnFOXO consists of only the DNA-binding domain of FoxO3a (aa 141–266), which allows it to bind to DNA but not activate transcription. Because of the significant homology between the FOXO-DNA binding domains of the FOXO factors, this construct also has the potential to repress FOXO1- and FOXO4-dependent transcription (14-16). The EGFP expressing empty vector, pTRUF12-GFP, was used as a control plasmid for both the acutely anesthetized control group and the 12 hours of MV group. The rAAV9 pTRUF12-dnFOXO-GFP and pTRUF12-GFP were generated, purified and tittered at the University of Florida Gene Therapy Center Vector Core Lab as previously described (17).

Real-time PCR was used to verify expression of the dnFOXO construct in pTRUF12-dnFOXO-GFP treated animals compared to control animals. In addition, western blots for GFP were performed to verify the presence of the constructs in all animals (data not shown).

Experimental Protocol

Surgical Protocol

To prevent MV-induced activation of FOXO transcription in the diaphragm we delivered an AAV vector containing dnFOXO to the costal diaphragm via direct injection. This innovative technique is described in a recent report (18). Specifically, this method of gene transfer was reported to effectively transduce the rat diaphragm with no adverse side effects (18).

Mechanical Ventilation

Control animals were acutely anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg body weight IP). MV animals were tracheostomized and mechanically ventilated with a pressure-controlled ventilator (Servo Ventilator 300, Siemens) for 12 hours as previously reported (19).

Biochemical Measures

Western Blot Analysis

Diaphragm protein extracts were assayed as previously described (20). Membranes were probed for GFP (sc-8334), Bcl-2 (ab7973), cleaved caspase-3 (ab1136812) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), caspase-3 (#9665), beclin-1 (#3738), LC3B (#2775) (Cell Signaling Technology, Carlsbad, CA), cytochrome c (sc-7159) and α-tubulin (sc-58667) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

One microliter of cDNA was added to a 25 μl PCR reaction for real-time PCR using Taqman chemistry and the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection system (ABI, Foster City, CA) as previously described (20).

20S Proteasome Activity

The in vitro chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20S proteasome was measured fluorometrically (20).

Cathepsin L Activity

Cathepsin L activity was measured fluorometrically according to manufacturer's instructions (Abcam).

Measurement of In Vitro Diaphragmatic Contractile Properties

Upon sacrifice diaphragm contractile properties were measured as previously described (2).

Mitochondrial respiration

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption was measured in isolated mitochondria from diaphragm muscle using previously described techniques (21). The respiratory control ratio (RCR) was calculated by dividing state 3 by state 4 respiration.

Histological Measures

Electron Microscopy

Diaphragm samples were treated and prepared for electron microscopy examination and analyzed by the University of Florida ICBR Electron Microscopy Core Lab.

GFP staining

Sections were directly imaged using an inverted fluorescent microscope to visualize GFP expression using a 10X objective lens.

Myofiber Cross-Sectional Area

Sections from frozen diaphragm samples were cut at 10 microns using a cryotome (Shandon Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) and stained as described previously (19). CSA was determined using Scion software (NIH).

LC3 Immunohistochemistry

Diaphragm sections were stained using LC3 primary (Cell Signaling) and secondary (Alexa Fluro 488 goat anti-rabbit) reagents diluted in 1% BSA.

Apoptosis

The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase nick end labeling (TUNEL) method was employed using a histochemical fluorescent detection kit (Roche Applied Scientific, Indianapolis, IN).

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons between groups for each dependent variable were made by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and, when appropriate, a Tukey HSD (honestly significant difference) test was performed post-hoc. Significance was established at p < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Results

Systemic and biologic response to MV

Prior to the initiation of MV, no significant differences existed in body weight between the experimental groups. Importantly, 12 hours of MV did not significantly alter body weight between groups (p<0.05). In addition, heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), arterial partial pressures of O2 (PaO2), CO2 (PaCO2) and pH were all maintained relatively constant during MV with no significant differences existing between groups (Table 1). In addition, the colonic (body) temperature remained relatively constant (36°C-37°C) during MV. At the completion of the MV protocol, there was no visible indication of lung injury and no evidence of infection, indicating that our aseptic surgical technique was successful.

Table 1.

Animal heart rates, systolic blood pressure, arterial blood gas tensions, and arterial pH at the completion of 12 hours of mechanical ventilation. Values are means ± SE. Note that no significant differences existed between the experimental groups in any of these physiological variables.

| Physiological variable | MV | MV+dnFOXO |

|---|---|---|

|

Heart rate (beats/min) |

352±9 | 365.7±6 |

|

Systolic blood pressure (mm/Hg) |

103.2±4.7 | 109±2.9 |

|

Arterial PO2 (mm/Hg) |

85.0±3.2 | 81.5±2.5 |

| Arterial PCO2 | 33.8±2.4 | 35.4±1.6 |

| Arterial pH | 7.46±0.02 | 7.45±0.01 |

Inhibition of FOXO attenuates VIDD

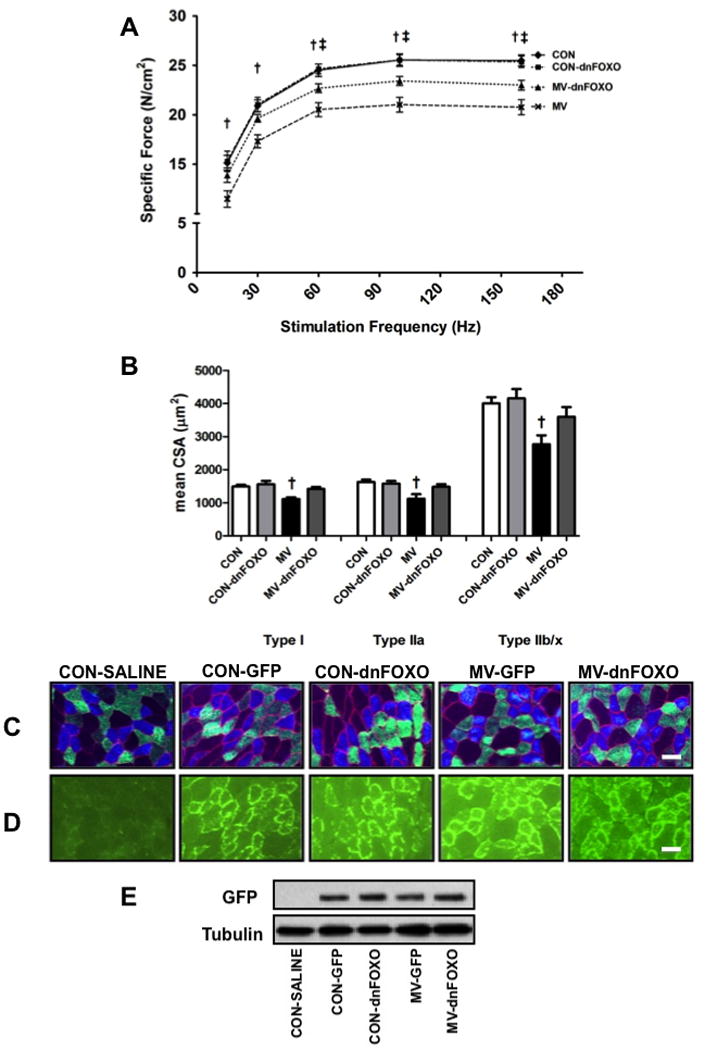

To determine if inhibition of FOXO transcription protects against VIDD we measured diaphragm muscle specific force production and diaphragm muscle fiber cross-sectional area (CSA). Similar to published reports, 12 hours of MV resulted in a significant reduction in diaphragm muscle force production. Importantly, treatment of control animals with dnFOXO resulted in no significant differences in diaphragm force production compared to control animals. Finally, treatment of MV animals with dnFOXO prevented the VIDD-associated decrease in diaphragm specific force production (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

A) Diaphragm muscle force-frequency response. B) Diaphragm muscle cross-sectional area in diaphragm skeletal muscle myofibers expressing myosin heavy chain (MHC) I (Type I), MHC IIa (Type IIa), and MHC IIb/IIx (Type IIb/IIx).. Values are mean ± SEM. Representative fluorescent staining of MHC I (DAPI filter / blue), MHC IIa (FITC filter / green), and dystrophin (Rhodamine filter / red) proteins in diaphragm samples are shown below the graph. Scale bars represent 50 μm. † MV significantly different versus all groups (p<0.05). ‡ MV-dnFOXO significantly different versus CON (p<0.05). C) Representative images depicting fiber type distribution. D) Representative images demonstrating fiber type localization of GFP. E) Representative GFP western blot. Groups represent: control (saline injected (no GFP)) animals (CON-SALINE), control GFP injected animals (CON-GFP), control dnFOXO injected animals (CON-dnFOXO), MV GFP injected animals (MV-GFP) and MV dnFOXO injected animals (MV-dnFOXO).

Diaphragm muscle CSA was also maintained in mechanically ventilated animals treated with dnFOXO compared to control animals (Figure 1B). Specifically, 12 hours of MV resulted in a significant reduction in muscle fiber CSA and treatment of mechanically ventilated animals with dnFOXO prevented the MV-induced diaphragm atrophy. In addition, treatment of control animals with dnFOXO did not result in any significant changes compared to the empty vector-injected control animals.

FOXO inhibition protects against MV-induced alterations to diaphragm ultrastructure

Electron microscopy images were obtained to visualize alterations to diaphragm ultrastructure that occur as a result of MV. Visual analysis of diaphragm muscle images from MV animals revealed: A) damage to the sarcomeric structure; B) an accumulation of lipid droplets; C) increased apoptotic mitochondria; and D) increased formation of autophagic vacuoles (Figure 2A-D). Administration of dnFOXO to mechanically ventilated animals maintained myofibrillar stability, organization of mitochondrial structure and reduced vacuole formation within the muscle. However, dnFOXO appeared to have no affect on the formation of lipid droplets in the diaphragm.

Figure 2.

Representative diaphragm muscle electron microscopy images for CON = control; non-ventilated, MV = mechanically ventilated for 12 hours, and MV-dnFOXO = mechanically ventilated for 12 hours; rAAV dnFOXO. A) White arrows depict the Z-line and black arrows depict the location of the A band (dark) and I band (light) of the sarcomere. B) White arrows depict lipid droplets. C) White arrows depict apoptotic mitochondria. D) White arrows depict autophagic vacuoles. Scale bars represent 2 μm.

FOXO-dependent regulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system during MV

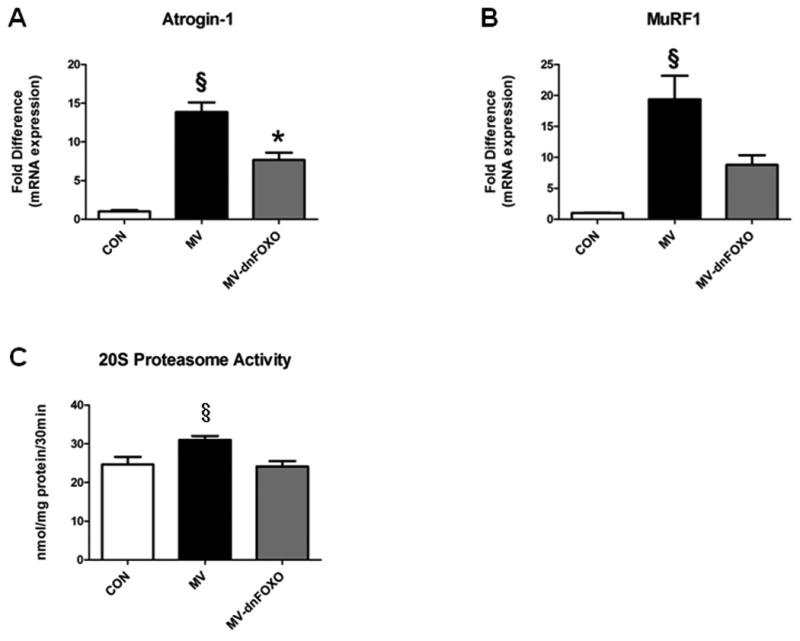

Atrogin-1/MaFbx and MuRF-1 are two muscle specific E3 ligases that are transcriptionally induced by FOXO. In this regard, our data demonstrates that MV results in a significant increase in the mRNA expression of both Atrogin-1/MaFbx and MuRF-1 and that inhibition of FOXO-specific translation results in an attenuation of these increases (p<0.05). However, expression of Atrogin-1/MaFbx was still elevated compared to control animals (Figure 3A-B). Finally, we also measured the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20S proteasome. Our results demonstrate that MV results in a significant increase in the activity of the 20S proteasome. However, this increase is significantly attenuated when FOXO activity is blocked (p<0.05) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

A-B) mRNA expression of Atrogin-1/MaFbx and MuRF-1. C) Chymotrypsin-like 20S proteasome activity. Values are mean ± SEM. § Significantly different versus CON and MV-dnFOXO (p<0.05). * Significantly different versus CON (p<0.05).

FOXO-dependent regulation of the autophagy/lysosomal system during MV

The autophagy/lysosomal system is responsible for the degradation of long-lived proteins, organelles and bulk cytoplasm by the formation of double membrane vesicles called autophagosomes, whose contents are degraded by lysosomal proteases (22). Initiation of autophagosome formation begins with the activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase complex Beclin-1/Vps34/Vps15. Prolonged MV increases the mRNA expression of Beclin-1 in the diaphragm, which is significantly attenuated in the MV-dnFOXO animals (p<0.05) (Figure 4A). However, no differences existed in the protein expression of Beclin-1 in the diaphragm between groups (Figure 4B). We also measured the diaphragm protein expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, which forms a complex with Beclin-1 to inhibit autophagy. Our results demonstrate a significant reduction in the protein levels of Bcl-2 in the MV group compared to CON and MV-dnFOXO animals (p<0.05) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

A) Beclin-1 mRNA expression. B) Beclin-1 protein expression. C) Bcl-2 protein expression. Values are mean ± SEM. Representative images are shown above the graph. § Significantly different versus CON and MV-dnFOXO (p<0.05).

LC3 also plays an important role in autophagosome formation and is transcriptionally regulated by FOXO. Our data demonstrates that MV results in a significant increase in the mRNA expression of LC3 as well as the ratio of LC3II to LC3I in the diaphragm. In addition, MV also causes an increase in the appearance of LC3 punctae in diaphragm muscle cross-sections. However, administration of dnFOXO to the diaphragm of animals prior to MV results in a significant attenuation in the mRNA expression of LC3 (p<0.05) as well as the appearance of LC3 punctae (Figure 5A-C).

Figure 5.

Diaphragm LC3 expression. A) LC3 mRNA expression. B) Ratio of LC3II/LC3I. Representative images are shown above the graph. C) Formation of LC3 punctae. Representative images depicting the formation of LC3 punctae within the diaphragm muscle fibers are shown above the graph. Sections were stained for myonuclei (blue) and LC3 (green). Arrows denote LC3 punctae. Values are mean ± SEM. § Significantly different versus CON and MV-dnFOXO (p<0.05). * Significantly different versus CON (p<0.05).

Finally, cathepsins are lysosomal proteases essential for degradation of the contents of the autophagosome. Specifically, cathepsin L has been demonstrated to be active in the diaphragm during MV and is also under transcriptional control of FOXO. Our data reveal that cathepsin L mRNA and activity in the diaphragm is significantly increased following 12 hours of MV compared to CON and treatment with dnFOXO resulted in a significant reduction of cathepsin L activity compared to MV. However, mRNA expression remained elevated compared to CON (p<0.05) (Figure 6A-B).

Figure 6.

A) Cathepsin L mRNA expression. B) Cathepsin L activity. Values are mean ± SEM. § Significantly different versus CON and MV-dnFOXO (p<0.05). * Significantly different versus CON (p<0.05).

FOXO-dependent alterations to MV-induced mitochondrial function and apoptosis

It has been demonstrated that MV results in diaphragmatic mitochondrial dysfunction and increased apoptosis (9, 21). Our results confirm these findings as prolonged MV resulted in a significant decrease in the RCR of diaphragm mitochondria (Table 2), and a significant increase in caspase-3 activity (Figure 7B). However, our results demonstrate that inhibiting FOXO transcription in the diaphragm during prolonged MV is sufficient to protect mitochondrial function as well as prevent caspase-3 activation. In regards to FOXO transcription, the pro-apoptotic mitochondrial protein BNIP3 is a known target of FOXO. Our results demonstrate that inhibiting FOXO transcription in the diaphragm during MV results in a significant reduction in the mRNA expression of BNIP3 and BNIP3L, compared to MV animals (Figure 7C-D). In addition, dnFOXO also results in a significant reduction in the MV-induced increases in cytosolic cytochrome c protein levels as well as the appearance of TUNEL positive nuclei in the diaphragm (Figure 7E; Figure 8)

Table 2.

Mitochondrial respiratory function in CON, MV, and MV-dnFOXO animals. These data were obtained using pyruvate/malate as substrates. Values are means ± SEM.

| CON | MV | MV-dnFOXO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| State 3 respiration (nmoles O2/mg/min) | 11.0 ± 0.35 | 7.76 ± 0.43§ | 10.9 ± 0.32 |

| State 4 respiration (nmoles O2/mg/min) | 2.2 ± 0.11 | 2.48 ± 0.10 | 2.6 ± 0.10 |

| RCR | 5.2 ± 0.13 | 3.2 ± 0.14§ | 4.4 ± 0.23* |

MV significantly different than CON and MV-dnFOXO (p<0.05).

MV-dnFOXO significantly different from CON (p<0.05).

Figure 7.

A) Procaspase-3. B) Cleaved caspase-3. C) BNIP3 mRNA expression. D) BNIP3L mRNA expression. E) Cytochrome C. Values are mean ± SEM. Representative images are shown above the graph. § Significantly different versus CON and MV-dnFOXO (p<0.05). * Significantly different versus CON (p<0.05).

Figure 8.

TUNEL positive nuclei. Values are mean ± SEM. Representative images of immunostained diaphragm tissue are shown above the graph. Sections were stained for nuclei (blue), TUNEL-positive nuclei (green), dystrophin (red). Arrows denote TUNEL positive nuclei. Scale bars represent 50 μm. § Significantly different versus all CON and MV-dnFOXO (p<0.05).

Discussion

These experiments provide new and important information regarding the role that FOXO signaling plays in ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction. Our results reveal that MV-induced increases in FOXO signaling are sufficient to contribute to diaphragm atrophy and contractile dysfunction. Specifically, activity of the FOXO family of transcription factors contributes to VIDD, at least in part, by increasing the expression of proteins required for the activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, the autophagy/lysosomal system and caspase-3. A detailed discussion of these findings follows.

Mechanical ventilation-induced contractile dysfunction and atrophy are linked to FOXO transcription

The FOXO family of transcription factors plays a significant role during various conditions that promote skeletal muscle atrophy (15, 23, 24). While four FOXO family members exist in mammalian cells, only FOXO1, FOXO3a and FOXO4 are present in skeletal muscle. In this regard, only FOXO1 and FOXO3a have been shown to increase during conditions that promote skeletal muscle wasting (i.e. fasting, cancer cachexia, disuse, MV and aging) (15). In this regard, it has been demonstrated that inhibition of FOXO transcriptional activity during immobilization-induced skeletal muscle wasting results in prevention of almost half of the inactivity-induced muscle fiber atrophy (24). Similarly, other groups have demonstrated a requirement for FOXO activity in limb muscle atrophy (16, 23, 25, 26). Importantly, the current experiments provide the first evidence that MV-induced diaphragm atrophy and contractile dysfunction is significantly attenuated when FOXO transcription is inhibited. However, disruption to sarcolemmal morphology and permeability, calcium homeostasis and release, or contractile protein concentrations may be responsible for the observed incomplete preservation of diaphragm specific force production compared to cross-sectional area.

Mechanisms of FOXO activation

While it is well established that FOXO is necessary for skeletal muscle atrophy during many conditions, the mechanisms leading to FOXO activation are not well defined. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that increased oxidative stress is an upstream regulator of FOXO signaling (27) and Hussain et al. recently hypothesized that both the autophagic and ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated protein degradation is triggered by oxidative stress and the upregulation of FOXO (8).

Additionally, FOXO is activated through alterations to AKT phosphorylation. During basal conditions, FOXO is targeted for phosphorylation by AKT, which results in reductions in transcriptional activity (8). Inhibition of AKT-mediated phosphorylation mobilizes FOXO factors to the nucleus where they induce gene expression (16, 23, 28). In this context, numerous studies of both animal and human patients suggest that MV alters AKT phosphorylation status (8, 11, 12).

Finally, Beharry et al. recently demonstrated FOXO acetylation status may also regulate FOXO transcriptional activity (29). These new findings suggest that FOXO is repressed under normal conditions by reversible lysine acetylation, and deacetylation of FOXO is sufficient to induce muscle atrophy (29).

Activation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by FOXO

The ubiquitin-proteasome system is activated in skeletal muscle to remove sarcomeric proteins during periods of accelerated proteolysis. While the importance of the E3 ligases are not well described during MV, several models of limb skeletal muscle atrophy have demonstrated that increased transcription of Atrogin-1/MaFbx and MuRF-1 contribute to skeletal muscle wasting (30-32). Additionally, both the mRNA and protein expression of Atrogin-1/MaFbx and MuRF-1 are increased in the diaphragm during prolonged MV (8, 9, 20, 33). Finally, during experimental conditions (i.e. antioxidant administration) where their expression is preserved at control levels, MV-induced diaphragm atrophy and contractile dysfunction are ameliorated (9, 20, 34). Therefore, it is feasible that the expression of the E3 ligases may contribute to the development of VIDD.

MV-induced activation of the autophagy/lysosomal system in the diaphragm is regulated by FOXO

In skeletal muscle, autophagy is a constitutively active process that is strongly induced during fasting, oxidative stress and denervation, resulting in significant muscle protein degradation (23, 28, 35, 36). Hussein et al. were the first to report the appearance of autophagosomes in the diaphragm of human MV patients, which was coincident with the significant induction of autophagy-related genes (8). However, the factors controlling the activation of these genes during MV have not been determined. In this context, our data demonstrates a significant induction of autophagy in the diaphragm during prolonged MV, which is inhibited if FOXO activation is knocked down. Specifically, the autophagy genes LC3, BNIP3 and cathepsin L are established FOXO target genes (16, 23, 38, 39). More importantly, our results reveal that prolonged MV promotes a significant increase in the expression of these genes in the diaphragm and this expression was attenuated in animals treated with dnFOXO. In addition, knockdown of FOXO was also sufficient to attenuate the increased appearance of LC3 punctae as well as autophagic vacuoles within the diaphragm muscle fibers. Together, these findings indicate that FOXO specific transcription of autophagy genes appears to play a significant role in increased autophagy in the diaphragm during MV.

Inhibition of FOXO transcription attenuates MV-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in the diaphragm

Prolonged MV results in VIDD due to increased mitochondrial ROS emission, which serves as a signal for activation of numerous proteolytic systems. Specifically, previous data demonstrates that mitochondria from the diaphragm of mechanically ventilated animals exhibit respiratory dysfunction as evidenced by impaired coupling (i.e., decreased RCR) (9, 21, 33). Damage to mitochondria can result in the enhancement of ROS production at complexes I and III (21). In addition, damage to mitochondria ultrastructure can alter mitochondrial membrane potential and result in mitochondria destruction due to rupture of the mitochondrial membrane and selective autophagy (i.e. mitophagy) of damaged mitochondria.

BNIP3 is transcriptionally regulated by FOXO and can contribute to mitochondrial damage (40, 41). Specifically, BNIP3 and its homolog BNIP3L are members of a subfamily of Bcl-2 related proteins that regulate apoptosis from both mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial sites by selective Bcl-2/Bcl-xL interactions. Under normal conditions endogenous BNIP3 is loosely associated with the mitochondrial membrane, but during conditions of cell stress, BNIP3 fully integrates into the mitochondrial outer membrane leading to mitochondrial dysfunction that is characterized by opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Therefore, increased transcription of BNIP3/BNIP3L may contribute to MV-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. In addition, our data also show an MV-induced increase in cytochrome c release, caspase-3 activity and the appearance of TUNEL positive nuclei, which is indicative of myonuclear apoptosis in the diaphragm. Importantly, inhibition of FOXO rescued the diaphragm from MV-induced mitochondrial dysfunction potentially due to a reduction in autophagic and apoptotic signaling.

Conclusions

VIDD is an important clinical problem that contributes to morbidity and mortality outcomes in patient populations experiencing weaning difficulties. This investigation provides the first evidence that increased transcription of atrophy-related genes by FOXO is necessary for the activation of key proteolytic systems essential for MV-induced diaphragm atrophy and contractile dysfunction. In the current study, inhibition of FOXO-specific transcription resulted in significant attenuation of target genes. However, mRNA levels of both Atrogin-1/MaFbx and Cathepsin L in the diaphragm remained elevated compared to controls. Therefore, it appears that these genes can be regulated through an alternate signaling pathway and this hypothesis warrants future exploration. Finally, while there are currently no clinically approved methods for targeting FOXO transcription due to the numerous cellular functions of FOXO, further insight into the function of FOXO in various disease states is essential to provide further understanding for the use of FOXO antagonists in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health awarded to S.K. Powers (R21 AR063805)

Drs. Smuder and Powers received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R21 AR063805). Dr. Sollanek's institution received grant support from the NIH.

Footnotes

Copyright form disclosures: The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Levine S, Nguyen T, Taylor N, et al. Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibers in mechanically ventilated humans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(13):1327–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers SK, Shanely RA, Coombes JS, et al. Mechanical ventilation results in progressive contractile dysfunction in the diaphragm. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92(5):1851–1858. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00881.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanely RA, Zergeroglu MA, Lennon SL, et al. Mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragmatic atrophy is associated with oxidative injury and increased proteolytic activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1369–1374. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200202-088OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tobin MJ, Laghi F, Jubran A. Ventilatory failure, ventilator support, and ventilator weaning. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(4):2871–2921. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laghi F, Cattapan SE, Jubran A, et al. Is weaning failure caused by low-frequency fatigue of the diaphragm? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(2):120–127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1246OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanely RA, Van Gammeren D, Deruisseau KC, et al. Mechanical ventilation depresses protein synthesis in the rat diaphragm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(9):994–999. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-575OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Betters JL, Criswell DS, Shanely RA, et al. Trolox attenuates mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction and proteolysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(11):1179–1184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-939OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussain SN, Mofarrahi M, Sigala I, et al. Mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragm disuse in humans triggers autophagy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(11):1377–1386. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0234OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powers SK, Hudson MB, Nelson WB, et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants protect against mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragm weakness. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(7):1749–1759. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182190b62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson WB, Smuder AJ, Hudson MB, et al. Cross-talk between the calpain and caspase-3 proteolytic systems in the diaphragm during prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(6):1857–1863. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318246bb5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine S, Biswas C, Dierov J, et al. Increased proteolysis, myosin depletion, and atrophic AKT-FOXO signaling in human diaphragm disuse. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(4):483–490. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1487OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClung JM, Kavazis AN, Whidden MA, et al. Antioxidant administration attenuates mechanical ventilation-induced rat diaphragm muscle atrophy independent of protein kinase B (PKB Akt) signalling. J Physiol. 2007;585(Pt 1):203–215. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.141119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed SA, Senf SM, Cornwell EW, et al. Inhibition of IkappaB kinase alpha (IKKalpha) or IKKbeta (IKKbeta) plus forkhead box O (Foxo) abolishes skeletal muscle atrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;405(3):491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dijkers PF, Birkenkamp KU, Lam EW, et al. FKHR-L1 can act as a critical effector of cell death induced by cytokine withdrawal: protein kinase B-enhanced cell survival through maintenance of mitochondrial integrity. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(3):531–542. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reed SA, Sandesara PB, Senf SM, et al. Inhibition of FoxO transcriptional activity prevents muscle fiber atrophy during cachexia and induces hypertrophy. FASEB J. 2012;26(3):987–1000. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-189977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, et al. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell. 2004;117(3):399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Zolotukhin I, et al. Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods. 2002;28(2):158–167. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smuder AJ, Falk D, Sollanek KJ, et al. Delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors to rat diaphragm muscle via direct intramuscular injection. Hum Gene Ther Methods. 2013 doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2013.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whidden MA, Smuder AJ, Wu M, et al. Oxidative stress is required for mechanical ventilation-induced protease activation in the diaphragm. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(5):1376–1382. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00098.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smuder AJ, Hudson MB, Nelson WB, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB signaling contributes to mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragm weakness*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):927–934. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182374a84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kavazis AN, Talbert EE, Smuder AJ, et al. Mechanical ventilation induces diaphragmatic mitochondrial dysfunction and increased oxidant production. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(6):842–850. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandri M. Protein breakdown in muscle wasting: Role of autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(10):2121–2129. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao J, Brault JJ, Schild A, et al. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 2007;6(6):472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senf SM, Dodd SL, Judge AR. FOXO signaling is required for disuse muscle atrophy and is directly regulated by Hsp70. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298(1):C38–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00315.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee D, Goldberg AL. SIRT1 by blocking the activities of FoxO1 and 3 inhibits muscle atrophy and promotes muscle growth. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.489716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandri M, Lin J, Handschin C, et al. PGC-1alpha protects skeletal muscle from atrophy by suppressing FoxO3 action and atrophy-specific gene transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(44):16260–16265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607795103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dodd SL, Gagnon BJ, Senf SM, et al. Ros-mediated activation of NF-kappaB and Foxo during muscle disuse. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41(1):110–113. doi: 10.1002/mus.21526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mammucari C, Milan G, Romanello V, et al. FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 2007;6(6):458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beharry AW, Sandesara PB, Roberts BM, et al. HDAC1 activates FoxO and is both sufficient and required for skeletal muscle atrophy. J Cell Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1242/jcs.136390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294(5547):1704–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1065874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baehr LM, Furlow JD, Bodine SC. Muscle sparing in muscle RING finger 1 null mice: response to synthetic glucocorticoids. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 19):4759–4776. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.212845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cong H, Sun L, Liu C, et al. Inhibition of atrogin-1/MAFbx expression by adenovirus-delivered small hairpin RNAs attenuates muscle atrophy in fasting mice. Hum Gene Ther. 2011;22(3):313–324. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smuder AJ, Min K, Hudson MB, et al. Endurance exercise attenuates ventilator-induced diaphragm dysfunction. J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(3):501–510. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01086.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClung JM, Whidden MA, Kavazis AN, et al. Redox regulation of diaphragm proteolysis during mechanical ventilation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(5):R1608–1617. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00044.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bechet D, Tassa A, Taillandier D, et al. Lysosomal proteolysis in skeletal muscle. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37(10):2098–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobrowolny G, Aucello M, Rizzuto E, et al. Skeletal muscle is a primary target of SOD1G93A-mediated toxicity. Cell Metab. 2008;8(5):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147(4):728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waddell DS, Baehr LM, van den Brandt J, et al. The glucocorticoid receptor and FOXO1 synergistically activate the skeletal muscle atrophy-associated MuRF1 gene. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(4):E785–797. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00646.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamazaki Y, Kamei Y, Sugita S, et al. The cathepsin L gene is a direct target of FOXO1 in skeletal muscle. Biochem J. 2010;427(1):171–178. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441(7095):885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Romanello V, Sandri M. Mitochondrial biogenesis and fragmentation as regulators of muscle protein degradation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12(6):433–439. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]