Abstract

Objective

To determine if urinary lipoarabinomannan (LAM) may serve as a biomarker to monitor antituberculosis (TB) therapy response, and whether LAM results before and after treatment are predictive of patient outcomes.

Design

Prospective cohort.

Setting

Outpatient referral clinic and tertiary hospital in South Africa.

Participants

Adults (≥18 years) with ≥2 TB-related symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss, night sweats) for ≥2 weeks being initiated on anti-TB therapy.

Interventions

On enrolment, we obtained urine and nebulised sputum specimens, offered HIV testing and started participants on anti-TB therapy for ≥6 months. We collected urine samples after the 2-month intensive treatment phase and at the completion of anti-TB therapy. Positive LAM results were graded from 1 (low) to 5 (high). Participants were followed for >3 years.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was change in urine LAM results during anti-TB therapy. The secondary outcome was all-cause mortality.

Results

Among 90 participants, 57 (63%) had culture-confirmed pulmonary TB. Among the 88 participants tested, 82 (93%) were HIV-infected with median CD4 168/mm3 (IQR 89–256/mm3). During anti-TB therapy, the percentage of LAM-positive participants decreased from baseline to 2 months (32% to 16%), and from baseline to 6-months (32% to 10%) (p values <0.005). In multivariate longitudinal analyses, urine LAM positivity and grade decreased among those with culture-confirmed pulmonary TB (p<0.0001), and had no change in sputum culture-negative participants. At the 2-month visit, participants with positive laboratory-based LAM or rapid LAM with ≥2+ grade had a significantly greater risk of mortality. In analyses adjusted for age, sex, baseline Karnofsky score and HIV status, participants with a rapid LAM ≥2+ grade after 2 months of anti-TB therapy had a 5.6-fold (95% CI 1.2 to 25.2) greater risk of mortality.

Conclusions

Rapid urine LAM testing may be a valuable tool to monitor anti-TB therapy response and to assess prognosis of patients being treated for pulmonary TB in HIV-endemic regions.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Stored urine samples were retrieved from a freezer for rapid lipoarabinomannan (LAM) testing.

The sample size was not powered to detect differences in measures of clinical improvement, which had not reached statistical significance.

An induced sputum sample for culture is an imperfect gold standard test for pulmonary tuberculosis (TB), which may have caused misclassification of urine LAM tests.

The primary strengths of our study were the longitudinal assessment of urine LAM during anti-TB therapy and the long follow-up period to assess patient outcomes.

Introduction

In 2012, approximately 1.3 million people died from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) worldwide, many of whom were coinfected with HIV.1 In South Africa, nearly two-thirds of people diagnosed with active TB are also coinfected with HIV.2 The HIV/AIDS epidemic has spurred a resurgence of TB, and new diagnostic tools are needed for diagnosing TB, monitoring a patient's response to treatment and evaluating the efficacy of various TB regimens.2–4 Reducing the global burden of TB may rely on improved diagnostics for initial case identification and monitoring response to anti-TB therapy, particularly among HIV-infected individuals.5 6

The estimated rate of treatment failure or disease relapse among patients receiving a standard 6-month regimen for drug-susceptible TB is 10%.5 A sputum specimen after the initial 2-month intensive treatment phase has been previously recommended as a prognostic marker of successful treatment.6 However, a recent meta-analysis found sputum smear microscopy for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and mycobacterial culture status after the intensive phase of therapy to be poor predictors of treatment failure or disease relapse.7 Consequently, the WHO recently downgraded sputum smear microscopy for AFB at the completion of the 2-month intensive phase of treatment to a conditional recommendation.8

A rapid clinic-based test for a pathogen biomarker might serve as a diagnostic tool for monitoring anti-TB therapy response and assessing a patient's prognosis.4 6 The Xpert MTB/RIF assay is more sensitive than sputum smear microscopy,9 but the assay's high cost and placement in centralised reference laboratories has reduced its potential clinical impact.10 Furthermore, since the Xpert assay is unable to discriminate between live and dead bacteria, it is not recommended for monitoring a patient's response to anti-TB therapy.11 Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) is a prominent glycolipid in the cell wall of TB and may serve as a useful pathogen biomarker to assess response to anti-TB therapy, particularly among HIV-infected adults.12 Therefore, we sought to determine if urinary LAM may serve as a biomarker to monitor anti-TB therapy response, and whether a positive LAM result after the 2-month intensive phase of therapy predicts mortality in an HIV-endemic region.

Methods

Study design and participant selection

We conducted a prospective cohort study of patients being initiated on anti-TB therapy at the Infectious Diseases referral clinic of King Edward VIII Hospital in Durban, South Africa from November 2008 to December 2010. The parent study was designed to assess the diagnostic value of an overnight oesophageal string, and has been previously reported.13 In brief, eligible participants were ≥18 years old, had a high probability of pulmonary TB based on the presence of at least two of four TB-related symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss, night sweats)14 for at least 2 weeks, and were either unable to produce a respiratory sputum sample or had at least two negative expectorated sputum samples for AFB by smear microscopy. We excluded patients who had a Karnofsky performance score <50, had taken anti-TB medications within the past 3 months, or had respiratory distress, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cardiac failure. We excluded any patients who improved after a short course of empiric amoxicillin, which was common practice for sputa smear-negative TB suspects in South Africa. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study procedures

On enrolment, we obtained a detailed social and medical history of participants who were admitted to the hospital for observation. For all participants, we performed early-morning sputum induction with 5% hypertonic saline using an ultrasonic nebuliser and obtained a urine sample. Respiratory samples were tested by smear microscopy for AFB and mycobacterial culture. All participants were then started on a standard, weight-based, fixed-dose combination of isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. Participants returned to the clinic each month, where nurses measured participants’ weight and recorded the number of TB-related symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss, night sweats). After each clinical encounter, a physician recorded whether, in their judgement, the participant was clinically improving or not. We collected additional urine samples at the end of the intensive treatment phase (2-month visit) and at the completion of anti-TB therapy (6-month visit). Sputum samples were obtained at the 2-month and 6-month visits among participants with a productive cough or clinical deterioration, which followed standard-of-care practices for TB treatment follow-up in South Africa. Participants who had improved after 2 months of standard anti-TB therapy were switched to isoniazid and rifampin for four additional months of anti-TB therapy. All participants were referred for initiation of antiretroviral therapy in accordance with South African guidelines.15

Laboratory testing

Direct microscopy for AFB was performed with both Ziehl-Nielsen and auramine stains. Mycobacterial culture was performed with liquid culture media (BACTEC MGIT BD, Sparks, MD, USA) and solid culture media. Positive cultures were identified as M. tuberculosis using the niacin test. All laboratory investigations were performed at accredited laboratories by technicians registered with the Health Professions Council of South Africa, and laboratory technicians evaluating specimens for positive mycobacterial smear and/or culture did not have access to LAM results.

Laboratory-based urine LAM testing was performed using an ELISA test, measured with a 340–750 nm spectral range microplate reader (Bio Rad Inc., Hercules, USA), and conducted by the same operator. Rapid LAM testing was performed on stored, frozen urine samples using the Determine TB LAM test (Alere Inc., Waltham, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's specifications.16 In brief, frozen urine specimens were brought to room temperature and centrifuged at 10 000 g for at least 5 min prior to testing. Using a sterile pipette, 60 µL of the clear supernatant of the urine sample was transferred to the test strip. Two readers (PKD and LG) independently interpreted the LAM test results after 25 min. Positive tests were graded from 1+ (lowest intensity) to 5+ (highest intensity), using the manufacturer's original reference guide with five positive categories. During rapid urine LAM testing, both readers were blind to participants’ identification and medical information.

Statistical analyses

Induced sputum culture for M. tuberculosis was the gold-standard diagnostic test for active pulmonary TB. For this pilot study, the estimated sample size was calculated with 30% urine LAM-positive at baseline and a 30% decrease in test positivity was observed after 2 months of therapy. Results were stratified by HIV-infection and CD4 count. We used Fisher's exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test to compare baseline characteristics between those rapid urine LAM positive and negative. We compared the urine LAM test results, both by percentage of participants LAM-positive and mean LAM grade, for follow-up visits against the baseline values using McNemar's test for paired binary outcomes and paired Student's t tests for continuous outcomes. We assessed clinical improvement by weight gain, evaluating resolution of TB-related symptoms, and physician assessment for clinical improvement independent of LAM results, in the month following urine LAM testing. We used multivariate repeated measure logistic and linear regression models for dichotomous and continuous measures stratified by sputum culture status. The urine LAM test grade was natural log transformed to approximate a normal distribution for regression analyses. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to display survival among participants by rapid urine LAM status after 2 months of anti-TB therapy; curves were compared using a log-rank test. We used Cox proportional hazard regression to assess relationships between laboratory-based and rapid urine LAM tests at baseline, 2 and 6 months of anti-TB therapy. Mortality from any cause was determined through the South Africa Department of Home Affairs national death registry. All regression models were adjusted for age and gender. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard regressions were also adjusted for baseline Karnofsky performance score and HIV status. Since CD4 count was not measured for all participants, we conducted separate multivariate Cox proportional hazard regressions with additional adjustment for baseline CD4 count. We provided 95% CIs, used two-tailed α<0.05 as significant, and conducted analyses using SAS (V.9.2).

Results

Among the 90 participants, the mean age was 36.9 years (SD±9.3 years) and 44 of the participants (49%) were woman (table 1). At enrolment, the mean body mass index was 21.8 kg/m2 (±3.5 kg/m2), 37 participants (41%) had a Karnofsky score ≤90 and 75 (83%) participants had 4 of 4 TB-related symptoms. Of the 88 participants tested for HIV, 82 (93%) were HIV-infected with a median CD4 cell count of 168/mm3 (IQR 89–256/mm3). Within this cohort, those eligible and started on antiretroviral therapy were started at a mean duration of 138.2 (SD±92.1) days after initiation of anti-TB therapy. Induced sputum samples from 14 participants (16%) were AFB smear-positive, and 57 (63%) participants had sputum culture-confirmed pulmonary TB.

Table 1.

Baseline cohort characteristics by rapid urine LAM test result (N=90)

| LAM negative (N=61) | LAM positive (N=29) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 37.6 (10.2) | 35.4 (7.3) | 0.25 |

| Female (%) | 28 (45.9) | 16 (55.2) | 0.50 |

| Clinical | |||

| Mean weight, kilograms (SD) | 59.8 (10.1) | 58.6 (11.4) | 0.69 |

| Mean BMI, kilograms/meter2 (SD) | 21.9 (3.4) | 21.5 (3.8) | 0.68 |

| Karnofsky performance score | 0.0008 | ||

| 100 (%) | 43 (70.5) | 10 (34.5) | |

| 90 (%) | 13 (21.3) | 6 (20.7) | |

| ≤80 (%) | 4 (6.6) | 12 (41.4) | |

| Number of tuberculosis symptoms* | 0.17 | ||

| 4 (%) | 48 (78.7) | 27 (93.1) | |

| 3 (%) | 8 (13.1) | 2 (6.9) | |

| 2 (%) | 5 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

| HIV testing (N=88) | |||

| HIV-infected (%) | 54 (91.5) | 28 (96.6) | 0.66 |

| Median CD4 count/mm3 among HIV+ (IQR) | 198 (102–270) | 106 (44–218) | 0.03 |

| Tuberculosis testing by sputum induction | |||

| AFB Smear Microscopy positive (%) | 8 (13.1) | 6 (20.7) | 0.39 |

| Culture positive (%) | 33 (54.1) | 24 (82.8) | 0.004 |

Data are proportion of participants (%), unless otherwise indicated.

*Includes cough, fever, night sweats, weight loss.

AFB, acid-fast bacilli; BMI, body mass index (calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres); LAM, lipoarabinomannan.

In total, we tested 213 urine samples by both the laboratory-based and rapid LAM antigen assays, and we have previously reported the diagnostic accuracy of these tests.17 In brief, 20 (22%) and 29 (32%) participants had a positive baseline laboratory-based test and rapid urinary LAM test, respectively. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the laboratory-based urine LAM test were 32% (95% CI 20% to 45%) and 94% (95% CI 79% to 99%). The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the rapid urine LAM test were 42% (95% CI 29% to 56%) and 85% (95% CI 68% to 95%). Participants with a positive rapid urine LAM result at baseline had significantly lower Karnofsky performance scores and a significantly lower median CD4 count, compared to rapid urine LAM-negative participants (table 1).

Participants were followed for a median of 49 months (IQR 45.8–50.9 months) from the date of enrolment. All 90 participants who returned for follow-up visits provided a urine sample for LAM testing. Following South Africa's standard-of-care practices, 8 of 73 (11%) and 11 of 50 (22%) participants provided an expectorated sputum sample at the 2-month and 6-month follow-up visits, respectively. During the 3-year follow-up period, 25 (28%) participants died; 5 (6%) died while still receiving anti-TB therapy.

Urine LAM to monitor response to anti-TB therapy

During the course of anti-TB therapy, the overall percentage of rapid urine LAM-positive participants decreased from baseline to 2 months (32% to 16%), and from baseline to 6 months (32% to 10%) (table 2). Eighteen of the 29 (62%) LAM-positive participants at baseline became LAM-negative at the 2-month follow-up visit (p=0.0009). One person, who was LAM-negative and sputum culture-negative at baseline, became LAM-positive at the 2-month visit. After 6 months of anti-TB therapy, only five participants were LAM-positive. This included two participants who became LAM-positive for the first time at the 6-month visit. Therefore, 26 of the 29 (90%) LAM-positive participants at baseline became LAM-negative after 6 months of anti-TB therapy (p=0.004). The overall mean urine LAM test grade decreased from 0.7 (±1.3) at baseline to 0.5 (±1.3) at 2 months to 0.2 (±0.7) at the 6-month visit (both p<0.01). Similar results occurred among HIV-infected participants, and when stratified by CD4 above/below 100 cell/mm3.

Table 2.

Rapid urine LAM test result during 6 months of anti-TB treatment

| Baseline (N=90) | 2-Month follow-up (N=73) | p Value (baseline vs 2 months) | 6-Month follow-up (N=50) | p Value (baseline vs 6 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid urine LAM positive | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| All participants | 29 (32.2) | 12 (16.4)* | 0.0009 | 5 (10.0)† | 0.004 |

| HIV+ | 28 (34.1) | 12 (17.6) | 0.002 | 5 (10.6) | 0.007 |

| HIV+ and CD4 ≥100/mm3 | 14 (25.5) | 4 (8.2) | 0.01 | 3 (8.6) | 0.11 |

| HIV+ and CD4 <100/mm3 | 14 (51.9) | 8 (42.1) | 0.25 | 2 (16.7) | 0.06 |

| Rapid urine LAM grade | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | Mean±SD | ||

| All participants | 0.7±1.3 | 0.5±1.2 | 0.005 | 0.2±0.7 | 0.006 |

| HIV+ | 0.8±1.4 | 0.5±1.3 | 0.007 | 0.2±0.8 | 0.008 |

| HIV+ and CD4 ≥100/mm3 | 0.5±1.0 | 0.2±0.8 | 0.007 | 0.1±0.3 | 0.04 |

| HIV+ and CD4 <100/mm3 | 1.3±1.8 | 1.3±1.9‡ | 0.31 | 0.5±1.4 | 0.08 |

*1 culture-negative participant with negative baseline rapid urinary LAM became positive at the 2-month follow-up visit.

†2 culture-positive participants with negative baseline rapid urinary LAM became positive at the 6-month follow-up visit.

‡1 culture-positive participant with 1+ grade at baseline rapid urinary LAM became 3+ at the 2 month follow-up visit; this participant died during the study.

LAM, lipoarabinomannan; TB, tuberculosis.

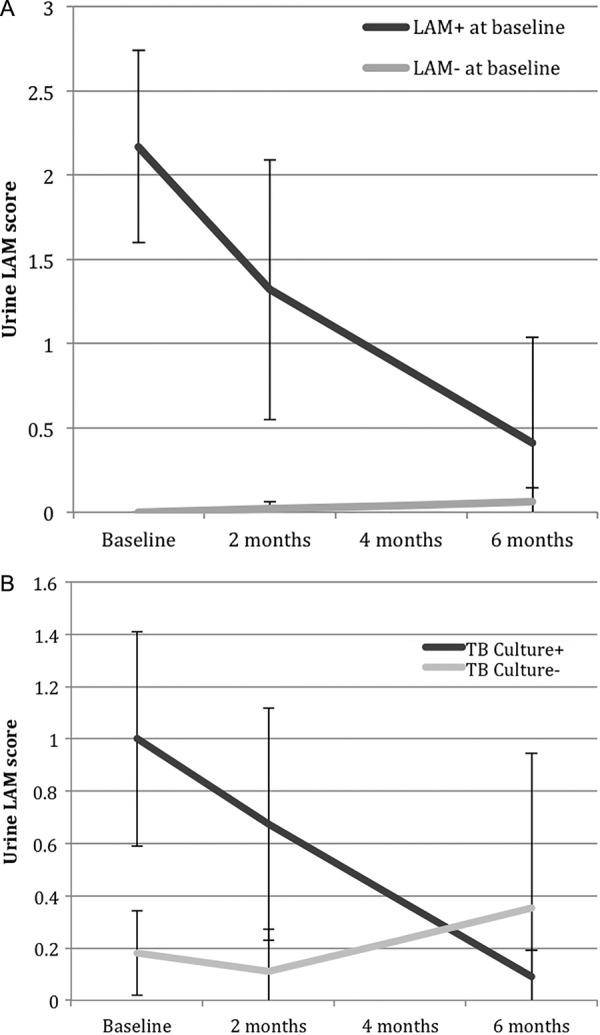

Among LAM-positive participants at baseline, the mean urine LAM grade decreased from 2.2 (±1.5) at baseline to 1.3 (±1.9) at 2 months to 0.4 (±1.2) at the 6-month visit (figure 1A). Within our cohort, only one LAM-positive participant at baseline had an increase in urine LAM grade during the study period (1+ to 3+ at the 2-month visit); this person died during the 6-month study period. Among LAM-negative participants at baseline, there was no appreciable change in LAM score during 6 months of anti-TB therapy. However, one participant had a 1+ grade at the 2-month visit, and two participants had a 1+ grade at the 6-month visit. In multivariate longitudinal regression models, rapid urine LAM test positivity and test grade decreased among LAM-positive participants at baseline (both p=0.0001), and had no significant change among LAM-negative participants at baseline, during 6 months of anti-TB therapy.

Figure 1.

(A) Rapid urine LAM grade during 6 months of anti-TB therapy for urine LAM-positive and LAM-negative participants at baseline. Error bars represent 95% CIs. We used natural-log transformed values of urine LAM grade to assess significant decrease for longitudinal regression models. (B) Rapid urine LAM grade during 6 months of anti-TB therapy for sputum culture-positive and culture-negative for pulmonary TB participants at baseline. Error bars represent 95% CIs. We used natural-log transformed values of urine LAM grade to assess significant decrease for longitudinal regression models (LAM, lipoarabinomannan; TB, tuberculosis).

Urine LAM positivity and grade decreased among those with culture-confirmed pulmonary TB during the course of anti-TB therapy (figure 1B). Among TB culture-positive participants at baseline, the proportion of those who were LAM-positive decreased from 27% at baseline to 14% at 2 months to 6% at the 6-month follow-up visit. Among those who were TB culture-positive, the mean urine LAM grade decreased from 1.0 (±0.4) at baseline to 0.5 (±0.4) at 2 months to 0.2 (±0.1) at the 6-month visit (figure 1B). In multivariate longitudinal regression models, culture-positive participants had a significant decrease in urine LAM test positivity and grade (both p<0.0001), while there was no significant change in urine LAM test positivity or grade among culture-negative participants.

We assessed the correlation between changes in the urine LAM result and clinical signs of response to treatment, including weight gain, resolution of TB-related symptoms and physician assessment for clinical improvement (table 3). Over the month following each clinical visit, LAM-negative participants had more average weight gain, better resolution of TB-related symptoms and a higher perception of clinical improvement by the physician, as compared to LAM-positive participants. However, these markers of clinical improvement did not reach statistical significance in this pilot study.

Table 3.

Clinical improvement by rapid urine LAM test result

| N | Weight change in the following month (kg) (mean±SD) | p Value | TB symptoms NOT resolving in the following month (mean±SD) | p Value | Clinical improvement in the following month (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline visit | |||||||

| Rapid LAM negative | 56 | 0.8±2.7 | 0.6±0.9 | 96.4 | |||

| Rapid LAM positive | 29 | −0.1±3.0 | 0.17 | 0.9±1.2 | 0.17 | 89.7 | 0.33 |

| 2-month follow-up | |||||||

| Rapid LAM negative | 60 | 0.7±2.4 | 0.6±1.0 | 90.0 | |||

| Rapid LAM positive | 12 | −0.5±3.6 | 0.16 | 0.8±1.1 | 0.41 | 83.3 | 0.61 |

| 6-month follow-up* | |||||||

| Rapid LAM negative | 45 | 1.0±1.8 | 0.2±0.5 | 100 | |||

| Rapid LAM positive | 5 | 0.4±0.9 | 0.52 | 0.4±0.9 | 0.41 | 100 | 1.00 |

*Data represent change from the 5-month to the 6-month follow-up visits.

LAM, lipoarabinomannan; TB, tuberculosis.

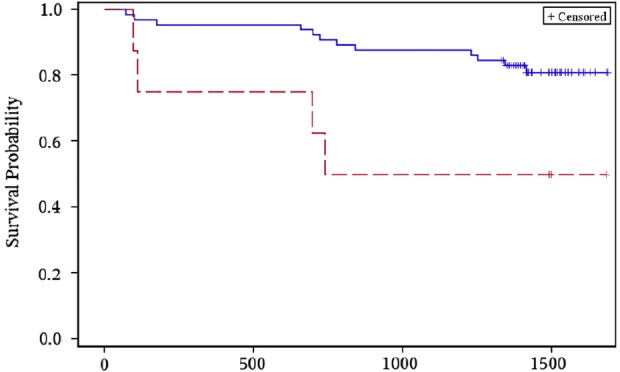

Urine LAM as a predictor of mortality

Participants with a positive laboratory-based or rapid LAM test result after the 2-month intensive treatment phase had a greater risk of mortality during the 3-year follow-up period (table 4). Participants with a strongly positive rapid urine LAM result (≥2+ grade) at the 2-month visit had an earlier median time to death (35.9 months), compared to participants with a weakly positive (1+ grade) or negative rapid urine LAM test (42.0 months) (p=0.02; figure 2). In univariate analyses, a positive laboratory-based LAM test or a rapid LAM grade ≥2+ at the 2-month visit was each significantly associated with all-cause mortality. In multivariate analyses adjusted for age, gender, Karnofsky performance score and HIV status, participants with a positive lab-based LAM test or a rapid LAM grade ≥2+ had a 4.13 (95% CI 0.88 to 19.4) and 5.58 (95% CI 1.24 to 25.2) hazard risk of death from any cause. Adjusting for the baseline CD4 count in the multivariate proportional hazard regression for the rapid LAM grade ≥2+ led to similar significant results (HR=5.01; 95% CI 1.05 to 23.9). Participants with a positive rapid LAM test at the 6-month visit had an adjusted hazard risk of 42.1 (95% CI 1.87 to 952) for mortality during the follow-up period. The HR remained significant when adjusting the same multivariate regression analysis for baseline CD4 count (HR=55.3; 95% CI 2.06 to 1484). The lab-based or rapid LAM test results at baseline were not significantly associated with mortality during the 3-year follow-up period.

Table 4.

Urine LAM as a predictor of mortality among participants receiving anti-TB therapy

| Predictor | Number of deaths/number at risk (%) | Univariate HR (95% CI) | p Value | Multivariate HR* (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline visit | |||||

| Laboratory-based LAM negative | 19/70 (27.1) | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| Laboratory-based LAM positive | 6/20 (30.0) | 1.13 (0.45–2.83) | 0.79 | 1.19 (0.40–3.55) | 0.75 |

| Rapid LAM negative | 16/61 (31.0) | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| Rapid LAM positive | 9/29 (31.0) | 1.22 (0.54–2.76) | 0.63 | 1.41 (0.54–3.70) | 0.49 |

| Rapid LAM score <2 | 21/76 (27.6) | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| Rapid LAM score ≥2 | 4/14 (28.6) | 1.04 (0.36–3.04) | 0.66 | 0.99 (0.28–3.58) | 0.99 |

| 2-month visit | |||||

| Laboratory-based LAM negative | 12/64 (18.8) | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| Labratory-based LAM positive | 4/9 (44.4) | 3.05 (0.98–9.48) | 0.05 | 4.13 (0.88–19.4) | 0.07 |

| Rapid LAM negative | 12/61 (19.7) | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| Rapid LAM positive | 4/12 (33.3) | 2.00 (0.65–6.21) | 0.23 | 1.99 (0.52–7.65) | 0.32 |

| Rapid LAM grade <2 | 12/65 (18.5) | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| Rapid LAM grade ≥2 | 4/8 (50.0) | 3.63 (1.17–11.3) | 0.03 | 5.58 (1.24–25.2) | 0.03 |

| 6-month visit | |||||

| Rapid LAM negative | 4/45 (8.9) | 1.00 (reference) | – | 1.00 (reference) | – |

| Rapid LAM positive | 2/5 (40.0) | 5.56 (1.00–30.7) | 0.05 | 42.1 (1.87–952) | 0.02 |

*Models adjusted by age, gender, Karnofsky performance score and HIV status.

Rapid LAM result modelled as negative (grade <1) versus positive (grade ≥1), and grade <2 versus grade ≥2.

LAM, lipoarabinomannan; TB, tuberculosis.

Figure 2.

Rapid urine LAM grade <2 (solid blue line) versus ≥2+ grade (dashed red line) after 2 months of anti-TB therapy and time-to-event for all-cause mortality (LAM, lipoarabinomannan; TB, tuberculosis).

Discussion

In our setting, urinary LAM decreased during the 6 months of anti-TB therapy among TB culture-positive patients, and participants who were LAM-positive after completing the intensive phase of anti-TB therapy had a greater risk of mortality. The rapid urine LAM test returned results within 25 min and did not require additional reagents, machinery or highly trained laboratory microscopists. The results from this pilot study suggest that the rapid urine LAM assay may be a convenient, accessible tool to monitor anti-TB therapy response and to assess prognosis of patients being treated for pulmonary TB in HIV-endemic regions.

The diagnostic accuracy of the rapid LAM test has been reported in other hospital-based studies.18–22 In a retrospective study of hospitalised HIV-infected TB suspects in Cape Town, the rapid LAM test had a sensitivity of 66% and specificity of 66%, which increased to 90% when using a non-TB control group.18 Among hospitalised HIV-infected suspects in South Africa and Uganda, the rapid urine LAM test had a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 62–63% and 78–88%, respectively.19 20 Although these cohorts have generally included sicker hospitalised patients, the reported diagnostic test characteristics have been similar. Our study is unique in assessing the urinary LAM as a potential biomarker to monitor response to anti-TB therapy and assess prognosis of patients being treated for pulmonary TB. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to evaluate the rapid urine LAM test in this manner.

Our findings suggest that urinary LAM may be a valuable pathogen biomarker to monitor response to anti-TB therapy among patients being treated for pulmonary TB. Sputum culture has been used for treatment monitoring and as a surrogate measure for drug approval,23 but is a poor predictor of treatment failure or disease relapse.7 The early stoppage of a study of shorter treatment duration among patients who converted sputum culture after 2 months of therapy highlighted the limited role of sputum monitoring.24 Other studies have measured the rate of decline of viable TB in sputum during therapy as colony counts on agar, time to positivity in liquid culture or levels of TB antigen 85 and 85B RNA in sputum, but these tests are currently not suited to rapid clinic-based testing.25–28 In our study, few participants could provide an expectorated sputum sample at the 2-month and 6-month visits, but nearly all participants were capable of providing a urine sample. Measuring a pathogen biomarker in urine with a point-of-care lateral flow assay has many additional advantages over conventional sputum microscopy and culture, including reduced risk of transmission to healthcare workers.

These findings are biologically plausible, since patients with LAM being excreted in urine are likely to have a high bacillary load of TB.29 In our cohort, participants who were urine LAM positive at baseline had lower Karnofsky scores, more TB-related symptoms and a lower median CD4 count, all consistent with a higher burden of TB disease. However, decreasing urine LAM levels may simply represent a change in the balance between LAM release by dead or dying bacilli and limited renal excretion. A positive urine LAM after the intensive phase of anti-TB therapy may prompt further clinical evaluations, including drug-resistance TB and/or medication adherence. Since endogenous TB relapse may be a failure to eradicate metabolically less active bacilli remote from cavity sources, urine LAM testing may also be well suited to detect extrapulmonary bacilli.30

Our study has several strengths and limitations. We thawed stored urine samples for rapid LAM testing, which may not give the same results as fresh urine specimens. Since this was a pilot study, the sample size was not powered to detect differences in the clinical improvement of participants. An induced sputum sample for culture is an imperfect gold standard test for pulmonary TB; the cause of a participant's death was not available. Finally, we evaluated urine LAM as an outpatient diagnostic test among predominantly HIV-infected TB suspects in a TB-endemic region, and these results may not be generalisable to other populations or areas with low TB rates. The primary strengths of our study were the longitudinal assessment of urine LAM during anti-TB therapy and the long follow-up period to assess patient outcomes.

In conclusion, urine LAM testing may be an accessible method to monitor response to anti-TB therapy among patients being treated for TB in HIV-endemic, resource-limited settings. Rapid urine LAM test characteristics improved among HIV-infected people at risk of mortality and identified those in need of close observation. Since urine LAM testing has several appealing properties and may be used at the clinical point-of-care, a larger clinical trial is warranted to determine if a persistently positive urine LAM is associated with drug-resistant TB, poor medication adherence or absence of a therapeutic response.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the excellent work and valuable contributions of our research staff and nurses, and Thirumalai Govender for assistance in the chemical pathology laboratory. The authors graciously thank all of the men and women who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: PKD, LG, FS and M-YSM designed the study. PKD, LG, FS and M-YSM collected and assembled the data. PKD and AG performed the statistical analysis. PKD wrote the report, with inputs from PKD, LG, AG, FS, IVB and M-YSM. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Funding: This study was funded by the Medical Research Council of South Africa, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the KwaZulu-Natal Research Institute for TB and HIV (K-RITH), and the UK's Department for International Development. Dr Drain was supported by the Harvard Global Health Institute, the Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988), the Infectious Disease Society of America Education & Research Foundation (IDSA ERF) and National Foundation for Infectious Diseases (NFID), The Program in AIDS Clinical Research Training Grant (T32 AI007433), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (K23 AI108293), the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI060354) and the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research. Dr Bassett was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH090326 (IVB) and the Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award (IVB).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Biomedical Research Ethics Committees of the University of KwaZulu-Natal approved the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The participant data set and statistical code are available from the corresponding author (Paul Drain, MD, MPH; pdrain@partners.org).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global TB Report 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Joint TB/HIV Interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Getahun H, Harrington M, O'Brien R et al. . Diagnosis of smear negative pulmonary tuberculosis in people with HIV infection or AIDS in resource constrained settings: informing urgent policy changes. Lancet 2007;369:2042–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60284-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallis RS, Pai M, Menzies D et al. . Biomarker and diagnostics for tuberculosis: progress, needs, and translation into practice. Lancet 2010;375:1920–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60359-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dye C, Watt CJ, Bleed DM et al. . Evolution of tuberculosis control and prospects for reducing tuberculosis incidence, prevalence, and deaths globally. J Amer Med Assoc 2005;293:2767–75. 10.1001/jama.293.22.2767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keeler E, Perkins MD, Small P et al. . Reducing the global burden of tuberculosis: the contribution of improved diagnostics. Nature 2006;444(Suppl 1):49–57. 10.1038/nature05446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horne DJ, Royce SE, Gooze L et al. . Sputum monitoring during tuberculosis treatment for predicting outcome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:387–94. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70071-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Programme. Treatment of Tuberculosis guidelines. 4th edn. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boehme CC, Nabeta P, Hillemann D et al. . Rapid molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin resistance. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1005–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawn SD, Brooks SV, Kranzer K et al. . Screening for HIV-associated tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance before antiretroviral therapy using the Xpert MTB/RIF assay: a prospective study. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001067 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miotto P, Bigoni S, Migliori GB et al. . Early tuberculosis treatment monitoring by Xpert MTB/Rif. Euro Resp J 2013;39:1269–71. 10.1183/09031936.00124711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamasur B, Bruchfeld J, Haile M et al. . Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis by detection of mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan in urine. J Micro Methods 2001;45:41–52. 10.1016/S0167-7012(01)00239-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahid F, Thumbiran NV, Gounder L et al. . Diagnosis of smear negative HIV associated pulmonary tuberculosis: a comparison of sputum obtained by a novel intra-oesophageal device with induced sputum. Seattle: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: principles and recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. (WHO/HTM/TB/2013.04). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. Clinical guidelines for the management of HIV & AIDS in adults and adolescents. South Africa: Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alere Inc. DetermineTM TB LAM test. Waltham, USA. http://www.alere.com/au/en/product-details/determine-tb-lam.html (accessed 22 Mar 2013).

- 17.Drain PK, Gounder L, Grobler A, et al Point-of-Care Urine Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) for Diagnosis and Treatment Response of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Sputum Smear-Negative Suspects. 44th Union World Conference on Lung Health on November 2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peter JG, Theron G, van Zyl Smit R et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of a urine LAM strip-test for TB detection in HIV-infected hospitalized patients. Eur Respir J 2012;40:1211–20. 10.1183/09031936.00201711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorman S, Manabe Y, Nicol M et al. . Accuracy of Determine TB-Lipoarabinomannan lateral flow test for diagnosis of TB and HIV+ adults: Interim results from a multicenter study. Abstract of the 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infection Seattle, WA, 2012 Abstract #149aLB. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah M, Ssengooba W, Armstrong D et al. . Comparative performance of urinary lipoarabinomannan assays and Xpert MTB/RIF in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS 2014;28:1307–14. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakiyingi L, Moodley VM, Manabe YC et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid urine lipoarabinomannan test for tuberculosis in HIV-infected adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66:270–9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balcha TT, Winqvist N, Sturegard E et al. . Detection of lipoarabinomannan in urine for identification of active tuberculosis among HIV-positive adults in Ethiopian health centres. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:734–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avorn J. Approval of a tuberculosis drug based on a paradoxical surrogate measure. J Am Med Assoc 2013;309:1349–50. 10.1001/jama.2013.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson JL, Hadad DJ, Dietze R et al. . Shortening treatment in adults with noncavitary tuberculosis and 2-month culture conversion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:558–63. 10.1164/rccm.200904-0536OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein MD, Schluger NW, Davidow AL et al. . Time to detection of Mtb tuberculosis in sputum culture correlates with outcome in patients receiving treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. Chest 1998;113:379–86. 10.1378/chest.113.2.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallis RS, Perkins M, Phillips M et al. . Induction of the antigen 85 complex of M. tuberculosis in sputum: a determinant of outcome in pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 1998;178:1115–21. 10.1086/515701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davies GR, Brindle R, Khoo SH et al. . Use of nonlinear mixed-effects analysis for improved precision of early pharmacodynamic measures in tuberculosis treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006;50:3154–6. 10.1128/AAC.00774-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rustomjee R, Diacon AH, Allen J et al. . Early bactericidal activity and pharmacokinetics of the Diarylquinoline TMC 207 in pulmonary tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008;52:2831–5. 10.1128/AAC.01204-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorman S, Manabe Y, Nicol M et al. . Accuracy of Determine TB-Lipoarabinomannan lateral flow test for diagnosis of TB and HIV+ adults: Interim results from a multicenter study. 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infection Seattle, 2012 Abstract #149aLB. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boshoff HI, Barry CE III. Tuberculosis—metabolism and respiration in absence of growth. Nat Rev Microbiol 2005;3:70–80. 10.1038/nrmicro1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]