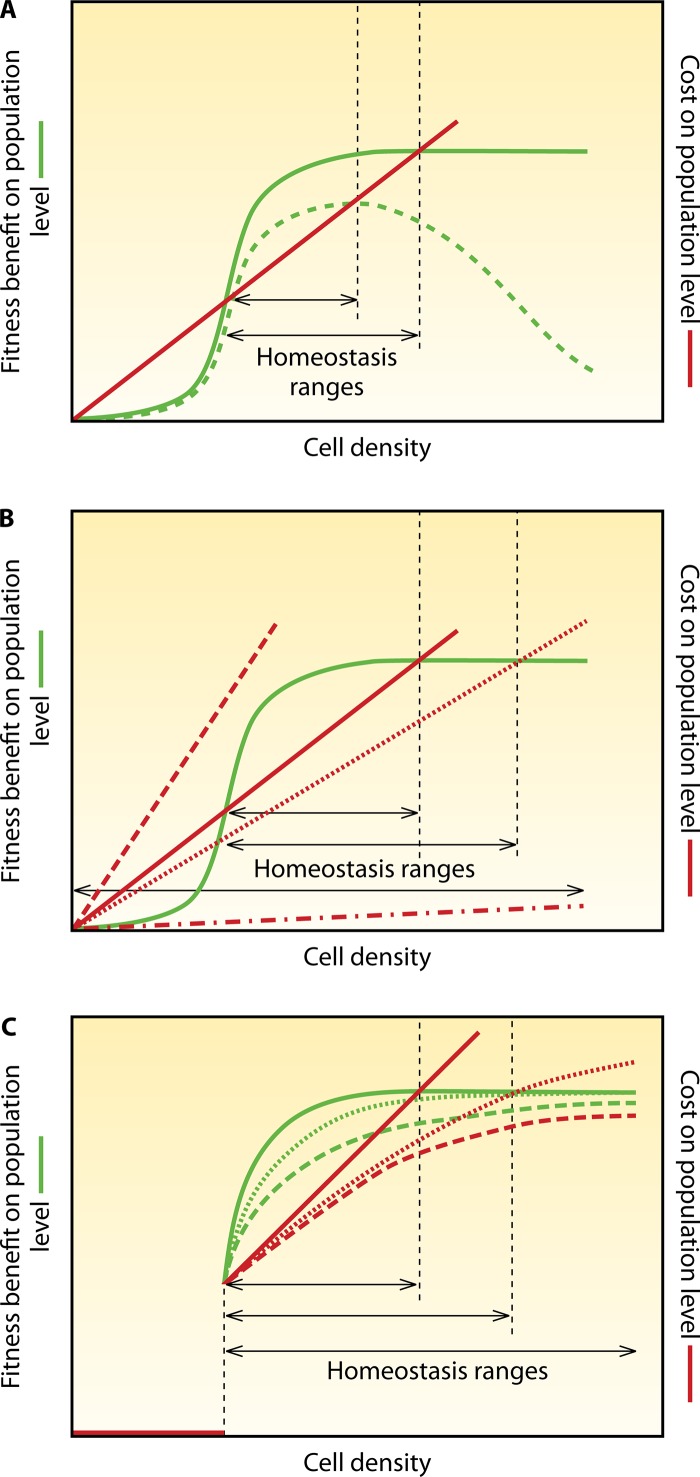

FIG 5.

Costs, benefits, and homeostasis in cooperative activities. (A) Variation in benefits. Shown are sketches of fitness benefit and cost, calculated as the sum of all individuals in a population over cell density (or cell number in the case of colonies). For simplicity, costs per cells are assumed to be constant; i.e., each cell contributes equally to cooperation. The benefit curve eventually approaches saturation, e.g., if all substrate is degraded by exoenzymes (green continuous line), or declines, e.g., if high concentrations of released toxins harm the producers (green dashed line). Consequently, the cell density range in which cooperation pays off changes (homeostasis range [indicated by arrows]); here, AI induction of cooperative activity can be expected. (B) Variation in costs. Different costs of cooperative behaviors (e.g., production of exoenzymes or antibiotics) influence the homeostasis range. The dashed line indicates cooperation that never pays off, and the dashed dotted line indicates cooperation that always pays off; in both cases, no AI regulation is required. The continuous and dotted lines indicate cooperation that pays off only in a certain cell density range (shown by the arrows). Here, AI control of cooperative activity can be expected. According to the metabolic prudence concept, the cost of cooperation can also vary for the same activity (162). In fact, variation in AI control in accordance with the metabolic prudency concept has been observed (125). (C) AI control of costs and benefits. AI control avoids the costs of cooperative behavior for low cell densities (continuous lines). Once induced by AIs, populations can subsequently reduce costs (dashed and dotted lines) and thus widen the homeostasis range, e.g., by downregulating the production of public goods by AIs in a density-dependent manner. If this is realized by individual cells switching from the producing to the nonproducing subpopulation, in principle, the homeostasis range can be infinite (dashed lines). However, if it is realized by decreasing the average production of public goods per cell, the cost curve will at some point cross the benefit curve, because the costs for the effector production machinery cannot be below a certain minimum value, and the regulatory machinery is costly (dotted lines). Note that these idealized graphs are meant to visualize principles. The same applies to Fig. 6 and 9. These graphs do not consider additional, interfering effects such as negative feedback via AI-regulated public goods or nutrient depletion.