Abstract

Purpose.

Soft tissue calcification is a pathological condition. Matrix Gla (MGP) is a potent mineralization inhibitor secreted by cartilage chondrocytes and arteries' vascular smooth muscle cells. Mgp knock-out mice die at 6 weeks due to massive arterial calcification. Arterial calcification results in arterial stiffness and higher systolic blood pressure. Intriguingly, MGP was highly abundant in trabecular meshwork (TM). Because tissue stiffness is relevant to glaucoma, we investigated which additional eye tissues use Mgp's function using knock-in mice.

Methods.

An Mgp–Cre-recombinase coding sequence (Cre) knock-in mouse, containing Mgp DNA plus an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES)-Cre-cassette was generated by homologous recombination. Founders were crossed with Cre-mediated reporter mouse R26R-lacZ. Their offspring expresses lacZ where Mgp is transcribed. Eyes from MgpCre/+;R26RlacZ/+ (Mgp-lacZ knock-in) and controls, 1 to 8 months were assayed for β-gal enzyme histochemistry.

Results.

As expected, Mgp-lacZ knock-in's TM was intensely blue. In addition, this mouse revealed high specific expression in the sclera, particularly in the peripapillary scleral region (ppSC). Ciliary muscle and sclera above the TM were also positive. Scleral staining was located immediately underneath the choroid (chondrocyte layer), began midsclera and was remarkably high in the ppSC. Cornea, iris, lens, ciliary body, and retina were negative. All mice exhibited similar staining patterns. All controls were negative.

Conclusions.

Matrix Gla's restricted expression to glaucoma-associated tissues from anterior and posterior segments suggests its involvement in the development of the disease. Matrix Gla's anticalcification/antistiffness properties in the vascular tissue, together with its high TM and ppCS expression, place this gene as a strong candidate for TM's softness and sclera's stiffness regulation in glaucoma.

Keywords: Matrix Gla, knock-in mice, reporter mice, trabecular meshwork, peripapillary sclera, glaucoma

Using mouse genetics, we show that the anticalcification/antistiffness gene Matrix Gla is highly expressed and specifically localized to the trabecular meshwork and peripapillary scleral region. The function of this gene might represent a sole mechanism affecting the source of two basic causes of glaucoma: elevated IOP and optic nerve damage.

Glaucoma is a complex optic neuropathy that results in irreversible blindness. It is well-established that elevated IOP is the principal risk factor associated with the development of the disease.1 Physiological and/or elevated IOP is determined by the resistance offered to aqueous humor flow by the trabecular meshwork (TM). The TM is a spongiform soft tissue formed by different types of endothelial-like cells, which use a variety of functions to regulate IOP. One of its most relevant functions is that which controls extracellular matrix (ECM) composition and deposition levels, which has been shown to have a direct correlation with increased flow resistance and glaucoma.2 Collagen and elastic fibers are key components of this extracellular space and contribute to the formation of the scaffold that helps maintaining the TM's unique architecture.3 Other tissues of the anterior segment assist the TM on its IOP regulatory function and contribute to modulations of IOP. Thus, the ciliary muscle, which intertwines posteriorly with the TM, affects IOP by contracting and pulling on the trabecular beams consequently opening spaces in the outflow pathway.4,5 Another tissue, the ciliary body, can modulate the outcome of total IOP by increasing or decreasing secretion of aqueous humor, which would then flow through the TM and cause decrease or increase of IOP. The elevated IOP generated in the anterior segment is transmitted to the back of the eye where the sclera senses the pressure fluctuations and exerts a biomechanical strain on the optic nerve (ON), contributing to the death of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs).6–8 It has been reported that the TM tissue from postmortem glaucoma patients is stiffer than that of controls.9 Also, it has been proposed that the degree of stiffness of the sclera might be an important determinant of the extent of susceptibility of ON damage in glaucoma.10,11

Identification of genes, which are involved in the function and pathology of any of the glaucoma associated eye tissues would not only provide further understanding of the mechanisms of the disease but will open the door to new therapeutics. Early studies from our laboratory had identified the Matrix Gla gene (MGP) among the 10 most highly expressed genes in the human TM.12,13 Transcription of the gene was altered by the mechanical forces of pressure and by other IOP-inducing agents such as TGF-β and dexamethasone.13,14 We had also shown that not only the gene, but the encoded MGP protein, was present in the TM tissue in its active conformation and that the activity of the enzyme responsible for its activation, γ-Carboxylase, was very high in the TM tissue.15

Matrix Gla binds calcium and is a potent inhibitor of calcification.16 While mineralization of bone and tooth is a physiological process, soft tissue calcification is a pathological condition. In cartilage, calcification leads to loss of plasticity and bone formation. In the cartilage, MGP is highly secreted by chondrocytes and is thought to be responsible for keeping the tissue from calcifying. In the arteries, where MGP is highly abundant in the vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) of the tunica media, calcification leads to formation of atherosclerotic plaques and calcified cartilaginous lesions.17,18 In patients, MGP polymorphisms have been linked to coronary artery calcification.19 An autosomal recessive rare disease, Keutel syndrome, has been associated with several mutations in the MGP gene.20–22 Patients develop abnormal soft tissue calcification and stenosis of pulmonary arteries. Although very few ophthalmologic exams have been described, in one case a 6-year-old patient had sudden loss of vision in both eyes at the age 3 and had bilateral ON atrophy.21

Matrix Gla–deficient mice die between 5 and 6 weeks of age due to massive arterial calcification. The mechanisms by which MGP inhibits calcification in the arteries are not totally understood. Earlier, it had been demonstrated that after binding to calcium, MGP binds and sequesters bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2), a potent stimulator of osteochondrogenic differentiation, and thus prevents chondrogenic transformation of the VSMCs.15,23,24 More recently, some investigators have shown that MGP may be inhibiting calcification by a direct effect on elastin. During calcification, the elastic lamina (dense layer of elastic fibers of the vessel wall) of large arteries is the first site of mineral deposition, with elastin, a major elastic lamina protein, acting as a mineral containing scaffold.25,26 Matrix Gla colocalizes with elastin in the arterial elastic lamina.25,26 It is known that calcium overload and calcification of elastic fibers lead to increase arterial stiffness as it was determined by measuring their elastic modulus and isobaric elasticity.27 It was also shown that such stiffness results in higher systolic blood pressure.27

Although gene expression studies by mRNA quantification had identified high expression of MGP in the human TM, attempts to localize the expression of this gene in the eye had met with little success. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry have been unable to detect endogenous MGP in the eye (our own unpublished results). To be able to elucidate a temporal and spatial pattern of expression of this gene in the eye, we made use of a set of mouse genetic tools. Engineered mouse lines carrying the Cre-recombinase bacteriophage gene under the control of a eukaryotic gene's regulatory sequences express the Cre enzyme in the eukaryotic gene's specific cell-type. When these mice are crossed with an engineered mouse line containing loxP sites flanking a STOP signal for a reporter gene, Cre recombines the two loxP sites to remove the STOP signal, which results in expression of the reporter gene. Histologic assessment of the reporter in the offspring of these crosses can reveal expression of the eukaryotic gene and accurately distinguish expression in neighboring cells. Thus, the generation of Cre-expressing mouse lines is extremely valuable for the determination of the desired gene expression in cell types, its temporal distribution during embryonic and adult development and its regulation under disease conditions. An accurate determination of these parameters is essential to establish a mechanistic link between MGP and glaucoma.

Therefore, to elucidate the expression pattern of Mgp in mice, we generated knock-in mice, in which an IRES-Cre recombinase expression cassette was inserted in between the translational Mgp STOP signal and its polyA (pA). This knock-in allele MgpCre was designed to express Cre recombinase only in cells where Mgp is expressed. Here, we describe the expression pattern of the MgpCre allele in the mouse eye.

Methods

Mouse Strains

All animal work was performed as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC; Chapel Hill, NC, USA), and conducted in accordance with the ARVO statement on the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic Research.

The mouse strains used in the study were: C57BL/6J albino mouse B6(Cg)-Tyr/J (B6 albino, stock # 000058; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) to obtain the recipient blastocysts, the production of chimeras and for the selection of the germline transmission; flippase recombinase (FLP) mouse B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(FLP1)Dym/RainJ (FLP deleter; stock # 009086; Jackson Laboratory) for the removal of the neomycin resistant gene (Neo) cassette; C57BL/6J (stock # 000664; Jackson Laboratory) for removal of the FLP gene and the Crb1 rd8 mutation; loxP flanked DNA STOP preventing expression of the lacZ gene, strain B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26 Sortm1Sor/J (R26R-lacZ; stock # 003474; Jackson Laboratory), for the production of the Mgp-Cre–mediated reporter expression.

Construction of an Mgp-Cre-Neo Knock-In Targeting Vector

The targeting vector was constructed at the BAC Engineering and Animal Models Core Facilities at UNC. The following steps were conducted to produce the Mgp-IRES-Cre-FRP-flanked PGK-Neo targeting vector: (1) An Mgp DNA fragment of 8.3 kb was retrieved from the C57 BAC RP23-108P5 clone into a pBS-DT plasmid (gift from C. Stewart; National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD, USA) by BAC recombinant technology and gap repair28 to yield a pBS-DT-Mgp, (2) a multielement plasmid carrying an IRES plus the Cre and flippase recognition target site (FRT)-flanked Neo cDNAs, plasmid pBS-IRES-mnCre-FRT-PGK-em7-Neo-FRT, was generated as follows:

a SwaI/SalI fragment from pWP1 (Addgene the nonprofit plasmid repository, https://www.addgene.org; in the public domain) containing the IRES-eGFP sequence was inserted into a pBSII-KS plasmid to produce pBS-IRES-eGFP;

a NcoI/SalI fragment from pmnCre (gift from P. Soriano; Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA) containing the mnCre cDNA, replaced eGFP in pB-IRES-eGFP and yielded pBS-IRES-mnCre; and

an EcoRI cassette from pGEM-FRT-PGK-em7Neo-FRT (gift from J. Cheng; UNC) containing the FRT-flanked PGK-Neo sequence was inserted into pBS-IRES-mnCre at the SalI site to obtain the final multielement construct.

(3) An AscI site was created in the pBS-DT-Mgp vector after the Mgp TAG stop signal, and (4) a Xho/Xho fragment from the multielement plasmid containing the full IRES-Cre-Neo cassette was inserted into the pBS-DT-Mgp plasmid at the AscI site by blunt ligation to generate the final Mgp targeting vector, named hereafter pMgp-Cre-Neo knock-in (Fig. 1A). The 5′ arm of this vector contains 1972 bp Mgp promoter upstream sequences and the entire Mgp gene up to the STOP codon in the fourth exon (total length 5134 bp). The 3′ arm contains 210 bp of 3′UTR including the pA, plus 3022 of 3′ genomic sequences (total length 3232 bp; Fig. 1A). This vector (total 16,176 bp) places the Cre gene under the control of the Mgp promoter and all Mgp internal regulatory sequences. Confirmation of the correctness of the inserted DNA fragments and their junctions was validated by sequencing the inserted cassette and portions of its flanking arms (total of 4828 bp).

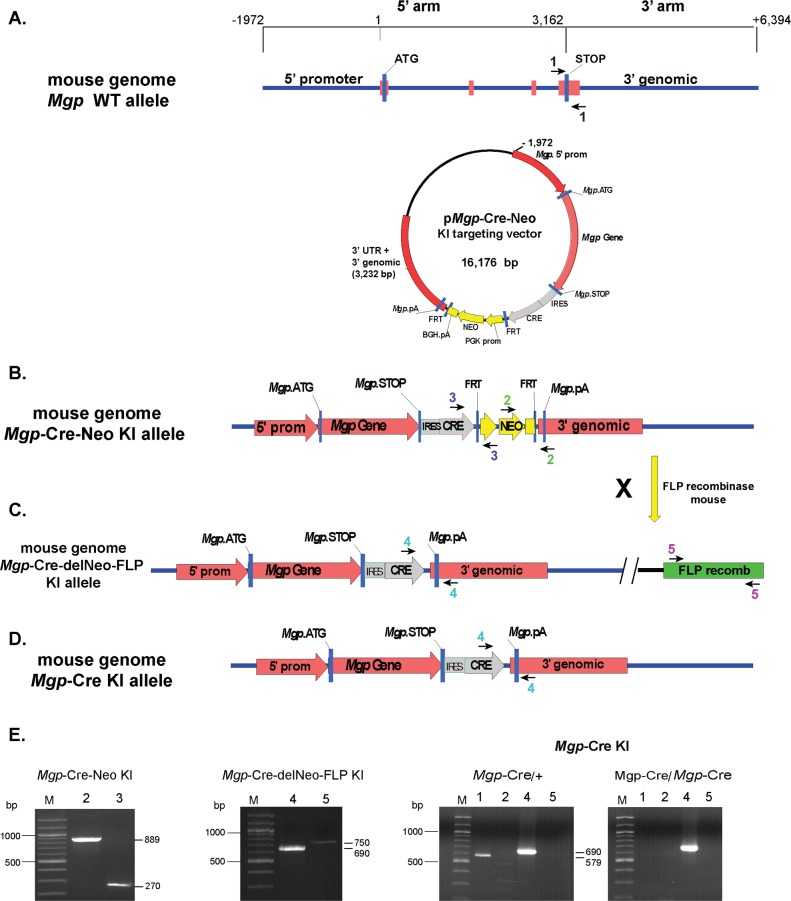

Figure 1.

Diagram of the targeting strategy to generate the Mgp-Cre knock-in allele. (A) The targeting vector consists of homology arms of 1972 promoter bp, exon 1, intron 1, exon 2, intron 2, exon 3, intron 3, exon 4, and of 3022 bp of 3′ genomic sequences (total 8.3 kb). Sequences containing the IRES-Cre-FRT-flanked neomycin resistance gene cassette were inserted between the Mgp STOP signal and the 3′UTR. (B, C) Targeted locus before and after the action of the FLP recombinase. (D) Final targeted locus after removing the FLP recombinase gene. The arrowheads denote the primer pairs used for genotyping (primer sequences in methods). (E) PCR was performed with the indicated primers pairs on genomic DNA from the knock-in lines carrying the corresponding alleles. pA, poly-adenylation sequence; KI, knock-in. All amplimers match the expected sizes.

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed using tail tip DNA, PCR with primers flanking the targeting vector integration sites, and identification of amplimers expected size by gel electrophoresis. Tail DNA extraction and amplification was conducted using a Red Extract-N-Amp Tissue PCR Kit (# XNAT; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, USA) following manufactures' specifications: mix of 10 μL red extract, 1.8 μL tissue extract solution, 1.8 μL neutralization buffer, and 6 μL of 1 μM each corresponding primers. PCR was followed at 94°C 2 minutes, (94°C 45 seconds, 57°C 40 seconds, 72°C 1 minutes) for 38 cycles, and ending at 72°C for 5 minutes before holding the temperature at 4°C.

The primers designed to identify the wild-type (WT) allele (Mgp+) were #1f 5′tgttctgggggaagagctctc3′ and #1r 5′atgtggttacacctccacac3′, which yields a 579 bp amplimer (Fig. 1A). For genotyping the Mgp-Cre-Neo knock-in allele (MgpCre-Neo), we used two sets of primers: #2f 5′aggatctcctgtcatctcaccttgctcct3′ and #2r 5′agtggatcctagcttggctgg3′, expanding Neo-Mgp 3′arm and yielding an 889 amplimer; #3f 5′ctggagtttcaataccggag3′ and #3r 5′ctcctcttcagacctgaagt3′, expanding Cre-Neo and yielding a 270 amplimer (Fig. 1B). For the Mgp-Cre-deleted Neo allele (MgpCre-delNeo, hereafter called MgpCre allele), #4f 5′ctggagtttcaataccggag3′ and #4r 5′atgtggttacacctccacac3′, which yields 690 bp amplimer. For the R26-FLP allele (R26FLP), we used #5f 5′cactgatattgtaagtagtttgc3′ and #5r 5′ctagtgcgaagtagtgatcagg3′, which amplify the FLP gene and yield a 750 bp amplimer (Fig. 1C).

For the R26R-lacZ nonrecombined allele (R26R+), we used #6f 5′ggagcgggagaaatggatatg3′ and #6r 5′aaagtcgctctgagttgttat3′, which yield a 650 bp amplimer. For the R26R-lacZ recombined allele (R26RlacZ), we used #7f 5′gcgaagagtttgtcctcaacc3′ and #7r 5′aaagtcgctctgagttgttat3′, which yield a 340 bp amplimer (in the public domain, http://jaxmice.jax.org/protocolsdb/f?p=116:2:::NO:2:P2_MASTER_PROTOCOL_ID,P2_JRS_CODE:13844,003474).

For the Crb1 WT allele (Crb1+), #8f 5′gtgaagacagctacagttctgatc3′ and #8r 5′ gccccatttgcacactgatga3′, which yield a 220 bp amplimer.29 For the rd8 mutation allele in the Crb1 gene (Crb1rd8), we used #9f 5′gcccctgtttgcatggaggaaacttggaagacagctacagttcttctg3′ and #9r 5′gccccatttgcacactgatga3′, which yield a 241 bp amplimer.

Tissue Collection and Histochemical Staining for β-galactosidase (β-gal)

Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation immediately prior to tissue collection. Whole globes were enucleated and incubated in fresh fixative (PBS containing 1% paraformaldehyde [PFA], 0.2% glutaraldehyde, 0.02% NP40, and 0.01% sodium deoxycholate) at 4°C for 1 hour. Eyes were then extensively washed with PBS and assayed for β-gal activity by incubating at 37°C overnight as described30 using solutions from the in situ β-Gal Staining kit (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Some of the globes were bisected at the equator before the staining. Isolated lens were also immersed in staining solution after carefully ripping apart the lens capsule and directly exposing the inside of the lens to the X-gal solution. After staining, tissues were washed again with PBS, post-fixed in cold 4% PFA for 30 minutes, washed with PBS/3% dimethyl sulfoxide, followed by PBS, rinse in distilled water, and transferred to 70% ethanol for delivery to the UNC histology core for paraffin embedding. Some of the stained whole eyes were post-fixed with 4% PFA, 2.5% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4°C, and embedded in Technovit GMA resin with Technovit GMA 7100 Hardener II (Heraeus Kulzer, GmbH, Bensheim, Germany) following described procedure.31,32

Histology

Paraffin blocks were sectioned at 5 μm by meridional orientation, sections mounted on glass slides (Superfrost Plus; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Technovit plastic blocks were equally sectioned at 3 to 5 μm on a Microm HM 355S Microtome (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sections were dried for 5 minutes on a 55°C hot plate (C&A Scientific, Manassas, VA, USA), stained with toluidine blue and cover-slipped with Permount mounting medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were taken on a model IX71 Olympus microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) equipped with a digital DP70 camera (Olympus) and software package (Olympus). Digital images were arranged with image analysis software (Photoshop CS; Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Results

Generation of an Mgp-Cre Knock-In Mouse Line

Molecular expression analyses have revealed that the MGP is one of the most abundant genes in the human TM,12,15,33,34 a level of expression that also translates into the mouse (our own unpublished data). However the localization and distribution of the MGP expression in the eye, and therefore the elucidation of its relevance in eye disease is unknown. This prompted us to use mouse genetics technology to generate an Mgp-Cre knock-in line that upon crosses with Cre-mediated reporter strains would allow to accurately determine the spatial and temporal expression of Mgp in the eye tissues. To do this we designed a targeting vector where an expression cassette containing an IRES-Cre-FRT-flanked Neo cDNA cassette was inserted in between 5′ and 3′ arms of the Mgp gene, rendering the Cre under the transcriptional control of the Mgp gene (Methods and Fig. 1A). The linearized vector was electroporated into Prx-B6N#1(C57BL6/N) ES cells and G418 resistant clones were screened for the gene targeting event. Correct targeting G418 resistant, positive-selected ES clones were confirmed by Southern Blot. Nine correctly targeted ES clones were injected into B6 albino recipient blastocysts to produce chimeras. Five chimeras were bred with B6 albino mice, and of these, two showed germline transmission of the MgpCre-Neo knock-in allele (Mgp-Cre-Neo line). The Neo cassette was subsequently excised from the two founder lines by crossing them with the FLP deleter mice to produce the line MgpCre-delNeo/+;FLP−/+ (Mgp-Cre-delNeo-FLP line). The introduced FLP gene was removed by intercrosses of the MgpCre-delNeo/+;FLP−/+ mice to produce the MgpCre-delNeo/+;FLP−/− mouse line (hereafter called MgpCre allele and Mgp-Cre knock-in line). Genotyping by PCR of all intermediate and final mouse lines (Methods) confirmed the presence and/or absence of each of the corresponding alleles. Thus, the Mgp-Cre-Neo knock-in line showed the 890 and 270 bp amplimers (Figs. 1B, 1E); the Mgp-Cre-delNeo-FLP line showed the 690 and 750 bp amplimers (Figs. 1C, 1E) and the final Mgp-Cre knock-in line showed the absence of the 890 and 750 bp amplimers and the presence of the 690 bp amplimers (Figs. 1B–E).

C57BL6/N mice have been recently shown to harbor the rd8 mutation in the Crb1 gene, which in the homozygous state causes retina degeneration.29 Because the ES cells used here to generate chimeras were from a 6/N mouse, the Mgp-Cre knock-in line was crossed with C57BL/6J WT mice to select for the absence of the rd8 mutation (MgpCre; Crb1+/+). Male and female cohorts exhibiting the 220 bp WT allele and lacking the 241 bp amplimer representative of the rd8 mutation were selected and bred for the maintenance of the Mgp-Cre knock-in line.

While Mgp KO mice die 5 to 6 weeks after birth, heterozygous MgpCre/+ and homozygous, MgpCre/Cre mice were viable, fertile, normal in size and phenotypically identical to their wild-type littermates, indicating that the transgenic knock-in was producing the correct Mgp protein.

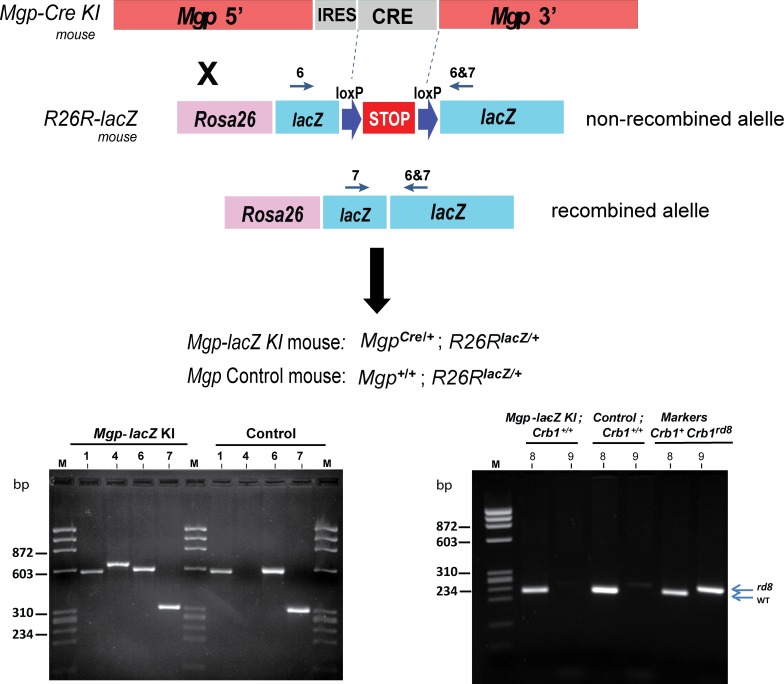

Functional Recombination of the Mgp-Cre Knock-In Mouse Line in the Mouse Eye

To determine the spatial and temporal pattern of expression of the Mgp gene (Cre activity) in the mouse, rd8 mutation-free mice (heterozygous and homozygous) knock-in progenies (MgpCre/+ and MgpCre/Cre) were crossed with the Cre-mediated reporter mouse line R26R-lacZ.35 This reporter mouse contains a STOP signal for the reporter gene β-gal flanked by loxP sites. The Cre recombinase, expressed under the Mgp control, recombines the two loxP sites to remove the STOP signal of the R26R allele, which results in expression of β-gal. This Cre-mediated recombination event is irreversible, therefore β-gal reporter expression can be identified in all cells expressing the Mpg gene. The mouse progeny obtained by crossing the Mgp-Cre line with the R26R-lacZ reporter was termed Progeny P (double heterozygous MgpCre/+; R26RlacZ/+; hereafter called Mgp-lacZ knock-in; Fig. 2, top). For this mouse, genotyping results showed the corrected amplimer's size for the four alleles: 579 (WT), 690 (Cre-delNeo Knock-in), 650 (R26R nonrecombined allele), and 340 bp (R26R recombined allele; Fig. 2, bottom left). Control mice, Mgp+/+; R26RlacZ/+ lacked the Mgp-Cre knock-in allele and were termed progeny Q (Fig. 2, bottom left). Confirmation of the rd8 mutation-free status for progeny P was obtained by genotyping its DNA with primer pairs #8 and #9 (Methods), using positive and negative controls (Fig. 2, bottom right).

Figure 2.

Generation of the recombinant Mgp-lacZ knock-in mouse. Top, an schematic representation of the cross between the Mgp-Cre Knock-in mouse and the Cre-mediated reporter R26R-lacZ to generate the Mgp-lacZ mouse. Bottom, genotyping of the genomic DNA from the Mgp-lacZ and control mice: left; primer pairs 1, 4 (Fig. 1) 6, and 7 (Jackson laboratories); right, primer pairs 8 and 9 to identify the rd8 mutation (primer sequences in methods).29 All amplimers match the expected sizes. Mgp-lacZ mouse does not harbor the rd8 mutation in the Crb1 gene. lacZ, β-galactosidase.

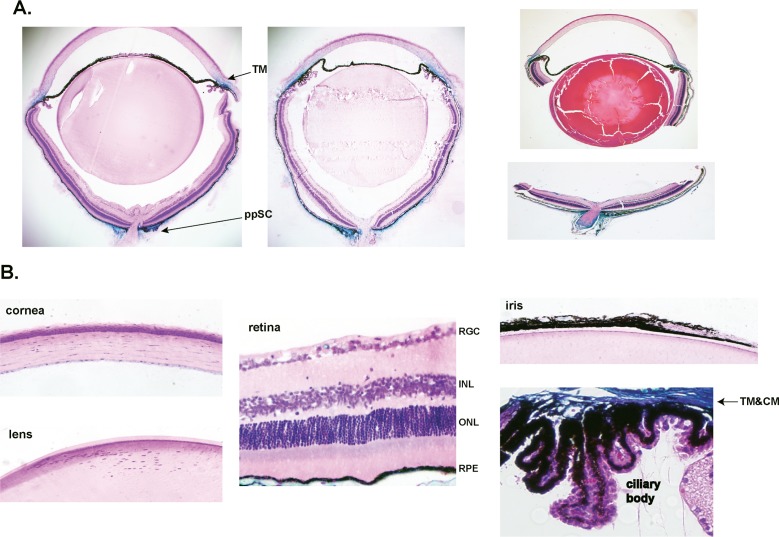

All mice from Progeny P showed functional recombination in the eye. In total, we examined and confirmed Cre-mediated expression in 43 experimental and eight control mice, ages 1 to 8 months from different breeding pairs and from two founders. The blue β-gal staining indicative of high levels of Cre activity was intense and consistently present in just two areas of the eye globe. The first area comprised the TM region, extending to the ciliary muscle and the suprascleral zone above the Schlemm's canal. The second area included the sclera tissue that surrounds the eye, in particular at the ppSC region surrounding the ON. The staining was equally observed when tissues were stained as whole globes (Fig. 3A, left) or after bisecting them (Fig. 3A, right). Both these areas, TM and ppSC region are well-established glaucomatous-relevant tissues. No expression was observed in the cells of the retina, iris, ciliary body, cornea, or lens (Fig. 3B). Blood vessels piercing through the retina were stained blue (VSMCs; see below, Fig. 6). Staining of lens cells was also negative after opening the capsule previous to X-gal treatment, in two double heterozygous positively blue mice (n = 4 lens; not shown).

Figure 3.

Functional recombination in Mgp-lacZ knock-in mouse line. Five-μm meridional sections from X-gal–stained MgpCre/+; R26RlacZ/+ eyes from 4- to 6-weeks old, and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections were from three different breeding pairs of one founder. (A) Stained whole globes embedded in Technovit plastic resin (two left images) and stained bisected eyes embedded in paraffin (right image). The expression of lacZ is readily detectable in only two regions of the eye: the anterior segment TM and the posterior segment ppSC. lacZ expression is also observed in the inner layer of the midsclera. (B) Detailed meridional sections of the cornea, lens, retina, and ciliary body from the same mouse. No lacZ staining was observed in these tissues. Occasional blue staining is seen in capillaries crossing the RGC cell layer. There is a clear demarcation between the ciliary body (not stained) and the TM, heavily stained. Expression of lacZ is limited to two glaucoma-relevant tissues. Original magnifications: (A) ×40 (B) ×200. INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; CM, ciliary muscle.

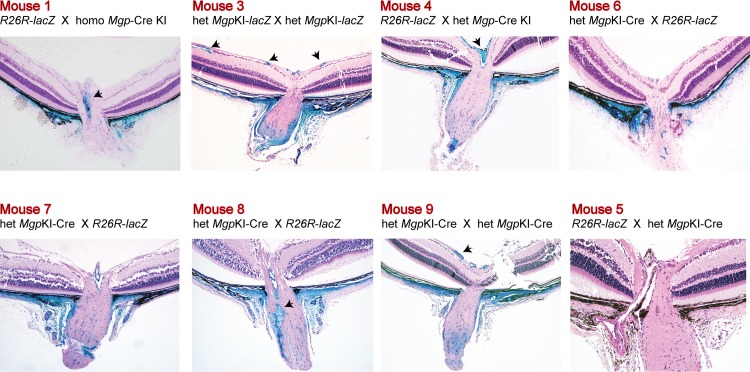

Figure 6.

Mgp Cre–mediated lacZ expression in the ONH region. Five-μm meridional sections from X-gal–stained eyes from 4- to 6-week-old and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mice 1, 3, and 4 are posterior segments of specimens shown in Figure 4. Mice 6 to 9 were from different breeding pairs. Mice 7 and 8 and 4 and 5 were littermates. Mouse 5 is the no Cre allele control (Mgp+/+; R26RlacZ/+). Eyes from mice 1, 6, 7, and 8 were stained as whole globes, with 1 and 6 embedded in Technovit plastic resin and 7 and 8 in paraffin. Mice 9 and 5 were stained as bisected specimens and embedded in paraffin. X-gal staining is very intense all across the sclera at the ppSC region indicating high expression of Mgp cre–mediated lacZ. Arrowheads: vascular smooth muscle cells from RGC vessels (mice 3 and 9) and retinal central artery (mice 1, 4, and 8) express abundant Mgp. All crosses resulted in a similar expression pattern. Original magnification: ×100.

Expression of Mgp-Cre in the Anterior Segment Is Restricted to Trabecular Meshwork and Immediate Surrounding Tissues

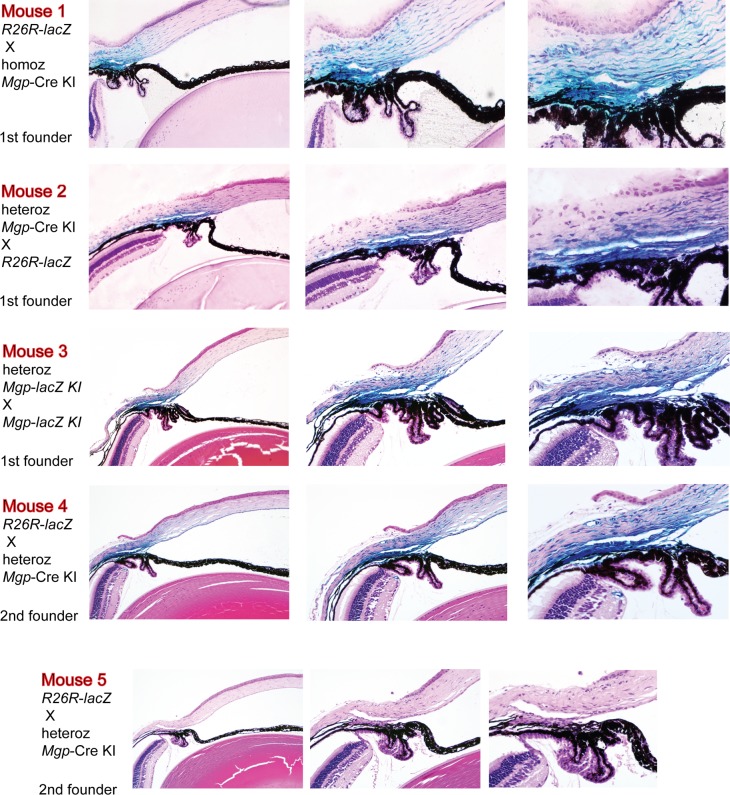

High resolution plastic- and paraffin-embedded sections from the anterior segment showed that the expression of Cre-mediated Mgp was specifically targeted to the entire outflow region including cells from the inner and outer walls of the Schlemm's canal, inner and outer walls, and scleral cells located above the outflow drainage area (Fig. 4). The Cre-mediated expression was remarkably intense in all layers of the TM. Cells from uveal, trabecular, and juxtacanalicular layers appeared deeply blue, indicating a high transcription level of the Mgp gene. The expression was sharply stopped just below the inferior region of the TM marking a clear expression/no-expression line in between the outflow tissue and the ciliary body. Likewise, expression was also clearly stopped at the anterior TM region and no cells of the cornea endothelium showed Cre-mediated activity. The ciliary muscle, which intertwines with the posterior region of the TM was also heavily stained. The location of expression was well conserved in all mice of the Mgp-lacZ line. Figure 4 shows a representative set of mice, all 4- to 6-weeks old, which originated from different breeding pairs, different combinations of homozygous and heterozygous Mgp-Cre knock-in, and from mice from a second founder, all mated with R26R-lacZ mice. Mice 1 to 4 were heterozygous progeny P (MgpCre/+; R26R lacZ/+), while mouse 5 was a progeny Q control (Mgp+/+; R26RlacZ/+). The localization of the Mgp Cre–mediated expression was nearly identical in all offspring. These histologic localization results allowed us to finely tune and define the original observation that the mRNA abundance of the MGP/Mgp's gene in the human and mouse from dissected TM tissue was among the highest expressed genes,12,13,33,34 and unpublished.

Figure 4.

Mgp Cre–mediated lacZ anterior segment expression. Five-μm meridional sections from X-gal–stained eyes from 4- to 6-week-old mice counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mice 1 through 4 were from different breeding pairs. Mice 4 and 5 originated from a second founder. Mouse 4 is the Mgp-lacZ double heterozygous (MgpCre/+;R26RlacZ/+) and mouse 5 is the littermate no Cre allele control (Mgp+/+;R26RlacZ/+). Eyes from mice 1 and 2 were stained as whole globes and embedded in Technovit plastic resin. Mice 3, 4, 5 were stained as bisected specimens and embedded in paraffin. All crosses resulted in a similar expression pattern. lacZ expression was confined to the TM region. Al layers of the TM were heavily stained with X-gal, including the Schlemm's canal inner and outer wall. High lacZ expression was also observed in the ciliary muscle and on the sclera cells above the outflow region. Original magnifications: left column: ×100, middle column: ×200, right column: ×400.

Expression of Mgp-Cre in the Posterior Segment Is Highly Efficient at the Peripapillary Scleral Region

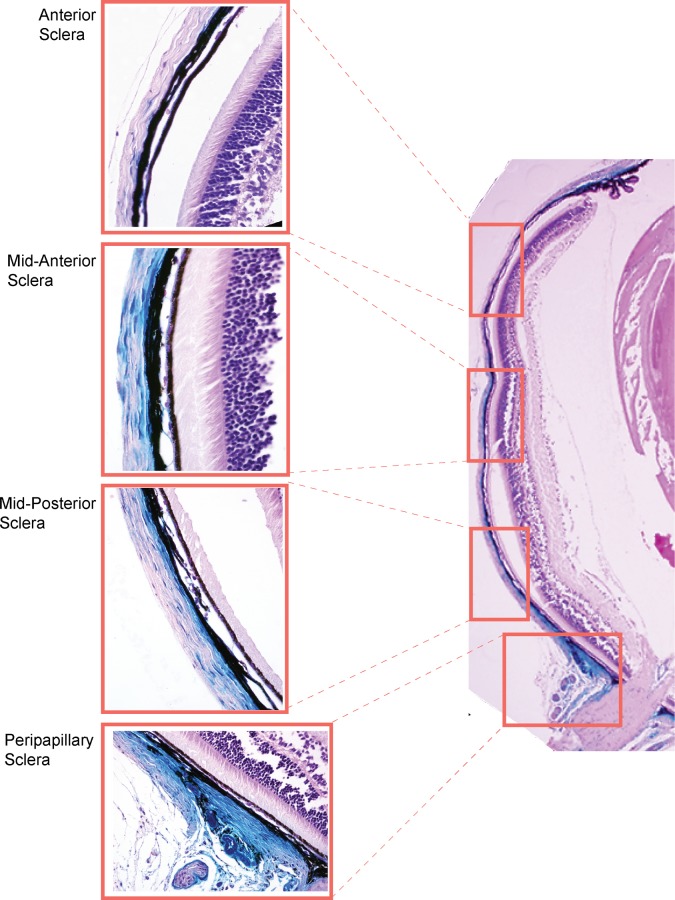

In the posterior segment, expression was restricted to the sclera. None of the cells of the retina, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), photoreceptors, glia, or RGCs show Mgp-Cre–mediated expression. In the sclera, staining was not observed at the periphery and started to be seen at the midanterior and posterior regions. The Mgp-Cre–mediated expression increased posteriorly and was mainly restricted to the sclera cell layer localized immediately underneath the choroid, while most of the outer scleral cells were not stained (Fig. 5). This particular scleral cell layer has been described as to be formed by chondrocytes in several animal species.36,37 Chondrocytes in other tissues, such as cartilage, exhibit high expression levels of the Mpg gene, which is responsible for maintaining their tissue softness. As it approached the ON region the whole width of the sclera was heavily stained, and the ppSC region surrounding the ON was completely blue (Fig. 6). As above, we examined eyes from different breeding pairs, from Mgp-Cre homozygous and heterozygous crosses with the R26R-lacZ mouse and from two founders. Figure 6 shows a representative set of seven eyes cross-sectioned through the ON and all of them exhibiting the same general expression pattern. All mice except mouse 5 were progeny P double heterozygous eyes. Mouse 5 was a progeny Q control which does not carry the Cre allele. We also observed Mgp-driven Cre expression in occasional sectioned vessels piercing through the retinal ganglion cell layer as well as in the retinal central artery. This observation fits well with the established known expression of this gene in the arteries, whose calcification leads to the death of the Mgp-KO mouse at 5 to 6 weeks of age. Together, these results indicate that the Mgp gene is an important component of the scleral region supporting the ON and that, given its natural function of inhibiting calcification, could have a key role in regulating the stiffness at the ppSC region.

Figure 5.

Mgp Cre–mediated lacZ expression in the sclera. Five-μm meridional section from representative MgpCre/+; R26RlacZ/+ 4.5-week-old mouse stained as a whole globe with X-gal, embedded in paraffin and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Expression of lacZ is not observed at the anterior sclera. It is beginning to show at the mid sclera and is highly expressed at the ppSC region. In the mid sclera, expression is mostly seen in the cell layer immediately underneath the choroid (chondrocyte layer).

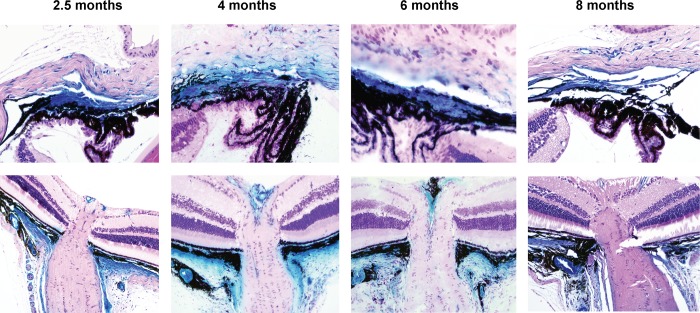

Mgp-Cre Activity Continues to Be Strong at 6 Months and Appears to Diminish at 8 Months

The Mgp-driven Cre expression, evaluated by the β-gal reaction, was observed at the same sites in mice of 2.5, 4, and 6 months while it appears to be diminished at 8 months (Fig. 7). This result indicates that the expression of the Mgp gene in the TM and supporting sclera is constantly required during adulthood. Confirmation of the localization of expression restricted to the TM and scleral supporting the ON was obtained by the same in situ enzymatic assay for β-gal in mice obtained from crossing the second founder with the R26R-lacZ mouse (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Mgp Cre–mediated lacZ expression with age. Five-μm meridional sections from representative X-gal–stained eyes from 2.5- to 8-months old and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Top row: TM region; bottom row: ONH region. The 2.5-month-old mouse images (TM and ONH) were from littermates, stained as bisected tissues and embedded in paraffin. The TMs and ONHs images of the 4- and 6-month-old mice were each from the same eye. The 4- and 6-month-old mice were from different breeding pairs, stained as whole globes, and embedded in Technovit resin. The 8-month-old mouse images are also from the same eye, stained as bisected tissues and embedded in paraffin. The 2.5- and 6 month-old mice are from the same litter. Expression of lacZ is very high up to 6 months of age and begins to diminish at 8 months, last time point tried. Original magnifications: Top row: ×400; bottom row: ×200.

Discussion

In living animals, the efficiency of a Cre-mediated recombination is very high, with only four Cre molecules required for one recombination event.38 Thus, detection of gene expression using the Cre-mediated expression approach is well above conventional methods and makes this technology an ideal tool to study specific and, most important, localized gene expression in living animals. In this study, an IRES-Cre gene was knocked-in into the Mgp gene of a living mouse after its translational STOP signal (Mgp-Cre knock-in line). In this engineered mouse, expression of Cre is under the control of the entire Mgp regulatory regions, and thus its expression represents a true Mgp-tissue specific expression. Crossing the knock-in mouse with the R26R-lacZ reporter, we demonstrated that the Mgp anticalcification/antistiffness gene in the eye is highly expressed in the glaucoma-associated tissues TM, ciliary muscle, and ppSC. This pattern of expression was consistent among mice from different breeding pairs and from different germline founders indicating a real Mgp localization in the mouse eye. Also, in the recombinant mouse, Mgp expression in noneye cartilaginous tissues agreed well with the known distribution pattern of the gene (unpublished results), supporting the same function of the gene in the eye.

In the TM, high levels of MGP expression and MGP IOP response have been shown by us and others to occur in dissected TM tissue/TM primary cells of humans and pigs using biochemical and molecular methods.12,13,15,33,34,39,40 By the same methods, our laboratory showed that such high presence in the TM was extended to the mouse eye (unpublished). However, histologic localization of gene expression is key for understanding a gene's role in disease and no MGP localization data was available for the eye of any species. Here, we show that Mgp expression is not strictly limited to the TM cells, but that it extends, albeit in a confined manner, to the immediately surrounding areas such as the ciliary muscle and sclera region above the Schlemm's canal. Given the anticalcification/antistiffness functions of the MPG gene in all other body systems, our results suggest that the presence of this gene in the outflow pathway and outflow surrounding regions is needed to maintain the appropriate softness and elasticity required to facilitate aqueous humor flow. Thus, the expression of Mgp not only in the TM, but on the ciliary muscle and immediate sclera above the canal emphasizes the importance of this gene in coordinating tissues involved in the regulation of IOP.

The second main site of Mgp gene expression in the eye was the sclera, in particular, the ppSC. Blue cells started appearing on the midsclera and were restricted to the layer immediately underneath the choroid. The expression continued to increase toward the posterior sclera and had the highest intensity and expansion at the ppSC supporting the ON. This result would indicate that the ppSC region is in need of a stronger protection from stiffness/calcification, and that would be mediated by the increased expression of Mgp. Because MGP is recognized as a key cartilage gene,17,20,41 our findings fit with, and also elucidate earlier sclera reports on the nature of scleral cells. It has been known that the inner portion of the sclera of many vertebrate species contains a cartilaginous layer in addition to the fibrous layer found in mammals.42 This scleral characteristic has been well-studied in myopia models in birds37,43 where chondrocytes were identified in the sclera of myopic eyes. Further, similar to what we observed on the mouse sclera with Mgp, it has been noted that the presence of chondrocytes displays regional differences, and is increased in the posterior sclera.43 Primary chondrocytes have also been isolated and characterized from the chick embryo sclera.44

In mammals, the presence of a cartilaginous sclera has been reported in rodents,45,46 and more recently in sheep, where it locates posterior to the tapetal fundus.36 Interestingly, a microarray hierarchical clustering analyses performed on cultured scleral cells from postmortem human donors showed a similar gene profile between the human sclera and cartilage tissues.47 In Fisher rats, the scleral cartilage is further converted to bone, and 95% of the rats showed a calcified sclera, a condition that increased with age and stress, and appeared to be sex dependent.46 It is worth noting that sclera calcification in humans had been reported as early as 1958 by David Cogan48 and that it has since been described several times during normal aging, and associated with disease conditions.49,50 Our findings, revealing the sclera expression pattern of the anticalcification Mgp gene, provide a first explanation of the likely mechanism responsible for the long observed eye sclera calcification.

The degree of stiffness of the sclera has great relevance in glaucoma. The sclera is the principal load-bearing structure of the eye and its biomechanical response to elevated IOP controls the extent of force applied on the optic nerve head (ONH)51,52 Deformation of the ONH due to the IOP-stresses is a clinical landmark of glaucoma and affects the axons and survival of the RGC cells. In the ppSC, scleral collagen and elastic fibers are circumferentially oriented around the ONH and provide a mechanical support in this region.10 Measurements of modulus of elasticity and tensile strength have determined that the elasticity of the sclera diminishes with age, thus increasing its stiffness.53,54 In the mouse, the structure of the sclera changes with pressure elevation showing alteration in fibrillar content and orientation, which would be consistent with increased stiffness.8,55 The presence of an anticalcification/antistiffness protein in the same specific scleral area where stiffness has proved to be an issue is intriguing, and a strong indication of the role of Mpg in protecting such region from elevated IOP and glaucoma. It would be logical to assume that a less stiff, more flexible sclera would be able to shock-absorb better IOP fluctuation forces and protect the ON.

Even using this sensitive expression technology, Mgp expression is not observed in the cornea, lens, iris, ciliary epithelium, or in any of cells of the layers of the retina. Although it has been described that the lens undergoes a calcification process with age and during cataract formation,56 no expression of Mgp was observed in the lens cells. This would agree with the authors' interpretation that calcification in the lens had no cellular participation.56 Overall, the lack of MGP expression in other than the glaucoma-associated tissues also indicate that the property of stiffness is not as important for them as it could be for the TM, ciliary muscle, and ppSC.

Although the majority of this first set of studies was targeted to the 1-month-old mouse, we examined mice up to 8 months of age. The fact that Mgp expression continues to be very strong at 6 months indicates the continuous need of preserving the softness of those glaucomatous-relevant tissues during adulthood. Although at this time quantification measurements are not available, there appears to be a decline in the expression observed at 8 months. If ratified, this decline would parallel the increased scleral stiffness found to occur with age in all species studied.8,10,53,53,55

Finally, there is always the possibility that MGP could have a totally novel function in the eye, and that the specific expression we are seeing would be responsible for a different outcome. However, given the extensive number of studies in the vascular and cancer field with this gene/protein, such speculation would seem unlikely. Even if that were to be the case, because the observed Mgp expression in the eye is restricted to glaucoma-associated tissues, it would be logical to assume that such new hypothetical function would also be involved in preventing the development of the disease. The fact that in the eye, MGP is expressed in tissues where calcification/stiffness could significantly alter their primary function is another indication that MGP uses its known function in the eye.

Experiments to investigate the function of the gene in knock-out mice are ongoing. The phenotype of this mouse though makes the study very limited.17 The reduced size of the animals, compromised breathing and premature death precludes an accurate analysis. The generation of an Mgp floxed mouse to circumvent early death is in progress.

In summary, using mouse genetics we have generated an Mgp-Cre knock-in mouse where the Cre recombinase is under the control of most, if not all regulatory sequences of the Mgp gene. Crosses of this mouse with a lacZ reporter strain have allowed for the first time to elucidate the location of expression of this gene in the mouse eye. In addition to its known presence in the TM, our study revealed specific Mgp expression in the sclera, which becomes particularly strong in the ppSC region. To our knowledge, Mgp is the first gene exclusively expressed in anterior and posterior tissues relevant for the development of glaucoma, strongly supporting the presence of a joint calcification/stiffness mechanism and offering the possibility of single targeting. As a key cartilage gene, Mgp would contribute to both, maintain the softness of the outflow region, and prevent the stiffness of the ONH area. The availability of this Mgp-Cre knock-in mouse is extremely valuable to investigate the response to glaucomatous insults in both regions of the eye in vivo. Future crosses of Mgp-Cre knock-in with fluorescent reporter mice will further allow performing such studies up longitudinally, in the same animal. Because Mgp's only known function (in the vascular, kidney, and cancer fields) is that of an anticalcification/antistiffness gene, our findings support that Mgp is a strong candidate for regulation of stiffness in glaucoma-associated tissues.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the UNC BAC Engineering and Animal Models core facilities for their guidance during the generation of the mouse strain and to members of the laboratory, Brandon Lane and Renekia Elliot for their support in the project.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY11906 (TB) and EY13126 (TB; Bethesda, MD, USA) and by an unrestricted grant from the Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY, USA) to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Disclosure: T. Borrás, None; M.H. Smith, None; L.K. Buie, None

References

- 1.Kass MA,, Heuer DK,, Higginbotham EJ,, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002; 120: 701–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lütjen-Drecoll E,, Shimizu T,, Rohrbach M,, Rohen JW.Quantitative analysis of ‘plaque material' in the inner- and outer wall of Schlemm's canal in normal- and glaucomatous eyes. Exp Eye Res. 1986; 42: 443–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lütjen-Drecoll E.Functional morphology of the trabecular meshwork in primate eyes. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999; 18: 91–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rohen JW,, Lutjen E,, Barany E.The relation between the ciliary muscle and the trabecular meshwork and its importance for the effect of miotics on aqueous outflow resistance. A study in two contrasting monkey species, Macaca irus and Cercopithecus aethiops. Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1967; 172: 23–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bárány EH.The mode of action of pilocarpine on outflow resistance in the eye of a primate (Cercopithecus ethiops). Invest Ophthalmol. 1962; 1: 712–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Downs JC,, Roberts MD,, Burgoyne CF.Mechanical environment of the optic nerve head in glaucoma. Optom Vis Sci. 2008; 85: 425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigal IA,, Ethier CR.Biomechanics of the optic nerve head. Exp Eye Res. 2009; 88: 799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cone-Kimball E,, Nguyen C,, Oglesby EN,, Pease ME,, Steinhart MR,, Quigley HA.Scleral structural alterations associated with chronic experimental intraocular pressure elevation in mice. Mol Vis. 2013; 19: 2023–2039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Last JA,, Pan T,, Ding Y,, et al. Elastic modulus determination of normal and glaucomatous human trabecular meshwork. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 2147–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girard MJ,, Suh JK,, Bottlang M,, Burgoyne CF,, Downs JC.Scleral biomechanics in the aging monkey eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 5226–5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen C,, Cone FE,, Nguyen TD,, et al. Studies of scleral biomechanical behavior related to susceptibility for retinal ganglion cell loss in experimental mouse glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 1767–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez P,, Zigler JS, Jr,, Epstein DL,, Borrás T.Identification and isolation of differentially expressed genes from very small tissue samples. Biotechniques. 1999; 26: 884–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comes N,, Borrás T.Individual molecular response to elevated intraocular pressure in perfused postmortem human eyes. Physiol Genomics. 2009; 38: 205–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez P,, Epstein DL,, Borrás T.Characterization of gene expression in human trabecular meshwork using single-pass sequencing of 1060 clones. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 3678–3693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue W,, Wallin R,, Olmsted-Davis EA,, Borrás T.Matrix GLA protein function in human trabecular meshwork cells: inhibition of BMP2-induced calcification process. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallin R,, Wajih N,, Greenwood GT,, Sane DC.Arterial calcification: a review of mechanisms, animal models, and the prospects for therapy. Med Res Rev. 2001; 21: 274–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo G,, Ducy P,, McKee MD,, et al. Spontaneous calcification of arteries and cartilage in mice lacking matrix GLA protein. Nature. 1997; 386: 78–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speer MY,, Yang HY,, Brabb T,, et al. Smooth muscle cells give rise to osteochondrogenic precursors and chondrocytes in calcifying arteries. Circ Res. 2009; 104: 733–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crosier MD,, Booth SL,, Peter I,, et al. Matrix Gla protein polymorphisms are associated with coronary artery calcification in men. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2009; 55: 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munroe PB,, Olgunturk RO,, Fryns JP,, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the human matrix Gla protein cause Keutel syndrome. Nat Genet. 1999; 21: 142–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hur DJ,, Raymond GV,, Kahler SG,, Riegert-Johnson DL,, Cohen BA,, Boyadjiev SA.A novel MGP mutation in a consanguineous family: review of the clinical and molecular characteristics of Keutel syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2005; 135: 36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khosroshahi HE,, Sahin SC,, Akyuz Y,, Ede H.Long term follow-up of four patients with Keutel syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2014; 164A: 2849–2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zebboudj AF,, Shin V,, Bostrom K.Matrix GLA protein and BMP-2 regulate osteoinduction in calcifying vascular cells. J Cell Biochem. 2003; 90: 756–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallin R,, Cain D,, Hutson SM,, Sane DC,, Loeser R.Modulation of the binding of matrix Gla protein (MGP) to bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). Thromb Haemost. 2000; 84: 1039–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaartinen MT,, Murshed M,, Karsenty G,, McKee MD.Osteopontin upregulation and polymerization by transglutaminase 2 in calcified arteries of Matrix Gla protein-deficient mice. J Histochem Cytochem. 2007; 55: 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spronk HM,, Soute BA,, Schurgers LJ,, et al. Matrix Gla protein accumulates at the border of regions of calcification and normal tissue in the media of the arterial vessel wall. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001; 289: 485–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niederhoffer N,, Lartaud-Idjouadiene I,, Giummelly P,, Duvivier C,, Peslin R,, Atkinson J.Calcification of medial elastic fibers and aortic elasticity. Hypertension. 1997; 29: 999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bouvier J,, Cheng JG.Recombineering-based procedure for creating Cre/loxP conditional knockouts in the mouse. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2009; Chapter 23:Unit. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Mattapallil MJ,, Wawrousek EF,, Chan CC,, et al. The Rd8 mutation of the Crb1 gene is present in vendor lines of C57BL/6N mice and embryonic stem cells, and confounds ocular induced mutant phenotypes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 2921–2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borrás T,, Rowlette LL,, Erzurum SC,, Epstein DL.Adenoviral reporter gene transfer to the human trabecular meshwork does not alter aqueous humor outflow. Relevance for potential gene therapy of glaucoma. Gene Ther. 1999; 6: 515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borrás T,, Buie LK,, Spiga MG,, Carabana J.Prevention of nocturnal elevation of intraocular pressure by gene transfer of dominant-negative RhoA in rats. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015; 133: 182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith RS,, Zabaleta A,, John SW,, et al. General and specific histopathology. : Smith RS, Systemic Evaluation of the Mouse Eye. New York, NY: CRC Press; 2002; 265–297. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wirtz MK,, Samples JR,, Xu H,, Severson T,, Acott TS.Expression profile and genome location of cDNA clones from an infant human trabecular meshwork cell library. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002; 43: 3698–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomarev SI,, Wistow G,, Raymond V,, Dubois S,, Malyukova I.Gene expression profile of the human trabecular meshwork: NEIBank sequence tag analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 2588–2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soriano P.Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999; 21: 70–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith JD,, Hamir AN,, Greenlee JJ.Cartilaginous metaplasia in the sclera of Suffolk sheep. Vet Pathol. 2011; 48: 827–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kusakari T,, Sato T,, Tokoro T.Visual deprivation stimulates the exchange of the fibrous sclera into the cartilaginous sclera in chicks. Exp Eye Res. 2001; 73: 533–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo FB,, Yu XJ.Re-prediction of protein-coding genes in the genome of Amsacta moorei entomopoxvirus. J Virol Methods. 2007; 146: 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vittitow J,, Borrás T.Genes expressed in the human trabecular meshwork during pressure-induced homeostatic response. J Cell Physiol. 2004; 201: 126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vittal V,, Rose A,, Gregory KE,, Kelley MJ,, Acott TS.Changes in gene expression by trabecular meshwork cells in response to mechanical stretching. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 2857–2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loeser R,, Carlson CS,, Tulli H,, Jerome WG,, Miller L,, Wallin R.Articular-cartilage matrix gamma-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein. Characterization and immunolocalization. Biochem J. 1992; 282(Pt 1); 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gottlieb MD,, Joshi HB,, Nickla DL.Scleral changes in chicks with form-deprivation myopia. Curr Eye Res. 1990; 9: 1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kusakari T,, Sato T,, Tokoro T.Regional scleral changes in form-deprivation myopia in chicks. Exp Eye Res. 1997; 64: 465–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seko Y,, Tanaka Y,, Tokoro T.Scleral cell growth is influenced by retinal pigment epithelium in vitro. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994; 232: 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshitomi M,, Boorman G.Eye and associated glands. : Boorman G, ed Pathology of the Fisher Rat. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1990; 239–259. [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Steen WK,, Brodish A.Scleral calcification and photoreceptor cell death during aging and exposure to chronic stress. Am J Anat. 1990; 189: 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seko Y,, Azuma N,, Takahashi Y,, et al. Human sclera maintains common characteristics with cartilage throughout evolution. PLoS One. 2008; 3: e3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cogan DG,, Hurlbut CS,, Kuwabara T.Crystalline calcium sulphate (gypsum) in scleral plaques of a human eye. J Histochem Cytochem. 1958; 6: 142–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong S,, Zakov ZN,, Albert DM.Scleral and choroidal calcifications in a patient with pseudohypoparathyroidism. Br J Ophthalmol. 1979; 63: 177–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patrinely JR,, Green WR,, Connor JM.Bilateral posterior scleral ossification. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982; 94: 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Downs JC,, Roberts MD,, Burgoyne CF.Mechanical environment of the optic nerve head in glaucoma. Optom Vis Sci. 2008; 85: 425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sigal IA,, Ethier CR.Biomechanics of the optic nerve head. Exp Eye Res. 2009; 88: 799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Avetisov ES,, Savitskaya NF,, Vinetskaya MI,, Iomdina EN.A study of biochemical and biomechanical qualities of normal and myopic eye sclera in humans of different age groups. Metab Pediatr Syst Ophthalmol. 1983; 7: 183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Friberg TR,, Lace JW.A comparison of the elastic properties of human choroid and sclera. Exp Eye Res. 1988; 47: 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pijanka JK,, Kimball EC,, Pease ME,, et al. Changes in scleral collagen organization in murine chronic experimental glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014; 55: 6554–6564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fagerholm P,, Lundevall E,, Trocme S,, Wroblewski R.Human and experimental lens repair and calcification. Exp Eye Res. 1986; 43: 965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]