Abstract

Various treatment options exist for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Clinical registries provide insight into routine treatment and identify changes in treatment over time. The Tumour Registry Lymphatic Neoplasms prospectively collects data on the treatment of patients with lymphoid B-cell neoplasm as administered by office-based haematologists in Germany. Data on patient and tumour characteristics, co-morbidities, systemic treatments, and outcome parameters are recorded. Eight hundred and six patients with CLL were recruited between May 2009 and August 2013. At the start of first-line treatment, median age was 71 years, 64% were male, and 44% had a Binet stage C disease. The most frequently used first-line/second-line regimens were bendamustine + rituximab (BR, 56%/55%), fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab (FCR, 22%/11%), and bendamustine (B, 5%/9%). Chlorambucil was used in only 7% (first-line) and 6% (second-line) of patients. Patients treated with FCR were younger and healthier than patients treated with BR. Overall, 91% of first-line treatments were successful (40% complete response). Real-life patient populations differ considerably from patients treated in randomized controlled trials. BR and FCR dominate the first-line and second-line treatments of CLL by office-based haematologists in Germany. Future analysis will investigate progression-free and overall survival times. © 2014 The Authors. Hematological Oncology Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, registries, ambulatory care, Germany/epidemiology, drug therapy/statistical and numerical data

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL, International Classification of Diseases 10 C91.1), a mature B-cell malignancy, is the most common type of leukaemia in the Western world [1]. In Germany, 4250 patients [2] are estimated to be diagnosed with CLL each year (3.0 per 100 000 according to the world standard population [3]). In the USA [4], the number is calculated to be 16 060 (4.3 per 100 000 according to the world standard population).

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is characterized by lymphocytosis in the peripheral blood, which is often diagnosed during routine check-ups [5]. Adequate immunophenotyping of the circulating lymphoid cells is mandatory to establish the diagnosis [6]. Advanced disease may be accompanied by cytopenias (anaemia or thrombocytopenia), lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly [1].

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia is a disease of the elderly: the median age at diagnosis is about 70 years [2,4], whereas only 10% of patients are younger than 50 years [7]. Course and prognosis of the disease vary widely. From the time of diagnosis, median survival ranges from 2 to over 10 years depending on patient's medical conditions and disease characteristics [8]. In the last decade, several serological, molecular, genetic, and immunophenotypic markers of prognosis have been established [8,9].

Binet's classification is widely used to characterize the status of CLL [10,11], whereas treatment decisions are guided by the International Workshop on CLL (IWCLL) consensus recommendation [6]. Standard treatment for patients with early stage disease (Binet A and B without active disease) is active surveillance (watch-and-wait strategy) [1,5,12]. Advanced as well as active disease (e.g. presence of B symptoms or Binet A with short lymphocyte doubling time or B/C with active disease) is treated systemically by chemotherapy, usually in combination with the CD20 antibody rituximab. The choice of the regimen is affected by multiple factors, such as patient's physical constitution and co-morbidities [1,5].

Currently, the combination of fludarabine with cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR) is recommended for the so-called fit patients [13]. Regimens recommended for all those with relevant co-morbidities are bendamustine based [14–16] or chlorambucil [17]. Allogeneic transplantation may be an option for selected fit, high-risk patients [18].

Today, most treatments of CLL can be delivered on an outpatient basis. In Germany, ambulatory care is predominantly provided by office-based specialists [19]. Patients with haematological malignancies such as CLL account for one of the largest proportions of patients treated by office-based haematologists in Germany [20]. Here, we present data on patients with CLL from the Tumour Registry Lymphatic Neoplasms (TLN) established by German office-based haematologists. This paper addresses the chemotherapeutic and immunotherapeutic treatments and changes since 2009. In addition, we show that patients with CLL in routine care differ in their sociodemographic as well as clinical characteristics from patients treated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Patients and methods

The open, prospective, longitudinal, observational, multicentre study TLN conducted by iOMEDICO in collaboration with the Arbeitskreis Klinische Studien and the Kompetenznetz Maligne Lymphome was established in 2009 to provide insight into the current treatment of lymphatic neoplasms by German office-based haematologists. The study was reviewed by an ethics committee and is registered with ClinicalTrial.gov registry (NCT00889798).

The clinical registry aims to recruit 3750 patients with aggressive or indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, CLL, or multiple myeloma. By the end of 2008, all members of the Association of Haematologists and Oncologists in Private Practice in Germany (BNHO e.V., in total 515 at that time) were asked to participate in the registry.

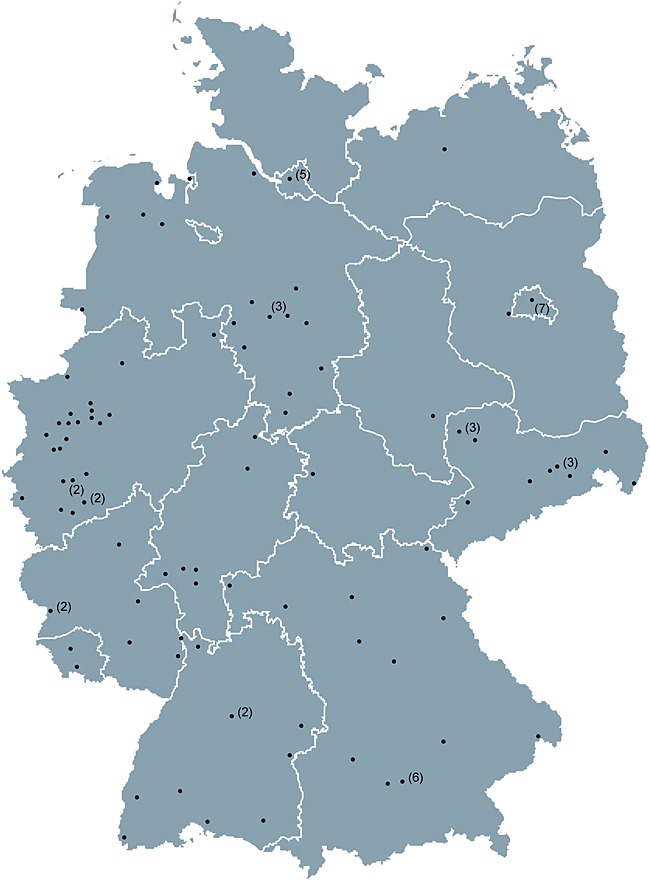

The TLN started recruiting in May 2009. By August 2013 (date of the present analysis), 115 study sites were actively participating. The distribution of the study sites across Germany is shown in Figure 1. Overall, 281 physicians are recruiting patients, accounting for over 30% of all office-based specialists within the field of haematology and oncology in Germany [19].

Figure 1.

Distribution of participating study sites across Germany. Numbers in brackets represent number of sites located in the same town

Patients of ≥18 years at the start of their first-line or second-line treatment are eligible for enrolment. Study sites recruit consecutively. Treatment starts within a period of 4 weeks prior until 8 weeks after written informed consent is signed.

At the time of enrolment data on patients' sociodemographics, tumour history, clinical parameters, and concomitant disorders are documented. Co-morbidity is assessed using the Charlson Co-morbidity Index [21]. During therapy, all systemic antineoplastic treatments (medication type and duration) as well as radiotherapies and/or surgeries are documented. Treatment outcome parameters include the best clinical tumour response according to the assessment performed by the study site, time to progression, and time of death by any cause.

Different from clinical trials, this study performed response evaluation on the basis of physical examination and blood cell count. It usually does not mandatorily include marrow biopsy as recommended for proper definition of complete remissions [1,6]. Clinical complete response (CR) as assessed in routine practice is based on normalized blood count and the absence of hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy.

Patients' data are transferred from medical records to a secure Web-based electronic case report form (eCRF) by physicians or trained study nurses and updated after any examination, change in therapy, or at least every 6 months. For quality assurance, data plausibility checks and queries are performed automatically by the eCRF software. To ensure the reliability of the database, site monitoring and checks on data completeness and plausibility are regularly performed by monitors and the data management.

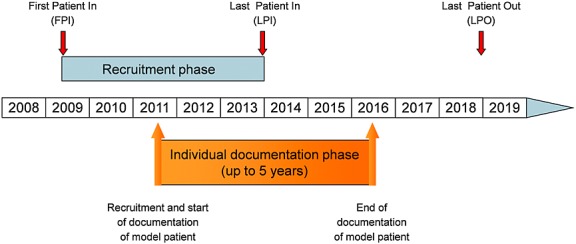

Patients are treated according to physicians' choice based on the patients' individual needs and schedules. No specifications are imposed to the physicians' assessment for treatment at any time. All patients are followed for 5 years from enrolment (or until death, loss to follow-up, or withdrawal of consent). Figure 2 shows an overview of the study time frame.

Figure 2.

Time frame of the Tumour Registry Lymphatic Neoplasms study

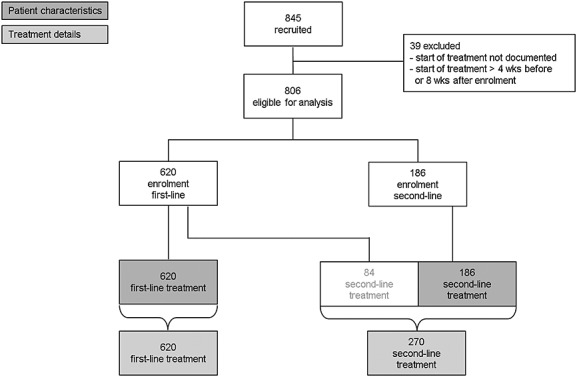

The present analysis is based on 806 patients with CLL recruited by 115 study sites between May 2009 and August 2013. Data on patients' characteristics are documented at the onset of treatment and are available for 620 first-line and 186 second-line patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Patient recruitment and treatment. Wks, weeks

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at the start of first-line treatment

Table 1 presents sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with CLL at the start of first-line treatment. Characteristics are shown for the entire cohort and for patients treated with one of the three most frequent regimens. Sixty-four per cent of patients are male. Median age at the time of diagnosis is 68 years and 71 years (range 21.3–92.1 years) at the onset of first-line treatment. Average body mass index (BMI) is 26 (men and women); 15% of patients are obese according to the World Health Organization definition (BMI > 30); 69% of patients have at least one co-morbidity, with cardiovascular disorders (44%) and diabetes (16%) recorded mostly. The average Charlson Co-morbidity Index of 0.8 and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (91% ECOG 0 or 1) indicate that at the start of treatment, most patients are in good general condition. Patients requiring therapy were in clinical stage Binet C (44%) or Binet B (36%) or symptomatic Binet A (20%). B symptoms are present in 29% of patients. The predominant B symptom is night sweats (23% of all patients). Splenomegaly is present in 63% of patients, and 66% of patients have more than two enlarged lymph node regions.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at time of enrolment

| Enrolment at first-line treatment |

Enrolment at second-line treatment |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 620) |

BR (n = 348) |

FCR (n = 137) |

B (n = 33) |

Total (n = 186) |

BR (n = 107) |

FCR (n = 21) |

B (n = 20) |

|||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age at primary diagnosis (n)a | 616 | 346 | 136 | 33 | 185 | 106 | 21 | 20 | ||||||||

| Median (years) | 67.8 | 68.0 | 61.3 | 74.0 | 66.3 | 66.6 | 60.1 | 67.2 | ||||||||

| Range (years) | 20.9–91.7 | 31.1–91.7 | 20.9–75.5 | 64.7–85.5 | 34.6–87.2 | 39.4–87.2 | 34.6–71.9 | 48.0–86.6 | ||||||||

| Age at start of therapy (n)b | 620 | 348 | 137 | 33 | 186 | 107 | 21 | 20 | ||||||||

| Median (years) | 70.8 | 71.2 | 64.6 | 77.6 | 72.5 | 72.4 | 67.0 | 73.0 | ||||||||

| Range (years) | 21.3–92.1 | 31.7–92.1 | 21.3–81.9 | 69.9–86.3 | 38.4–93.7 | 46.2–88.8 | 38.4–81.0 | 55.4–93.7 | ||||||||

| Male (%) | 64.2 | 65.2 | 71.5 | 54.5 | 57.0 | 57.0 | 57.1 | 50.0 | ||||||||

| BMI (n)a | 604 | 341 | 135 | 33 | 183 | 105 | 20 | 20 | ||||||||

| Mean ± SD (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 4.1 | 26.1 ± 3.9 | 26.2 ± 3.5 | 26.5 ± 5.4 | 26.3 ± 4.8 | 26.6 ± 5.1 | 26.3 ± 6.3 | 24.6 ± 2.2 | ||||||||

| Obese >30 (%) | 15.4 | 14.7 | 17.0 | 18 | 16.4 | 18.1 | 20.0 | — | ||||||||

| ECOG performancea | 571 | 320 | 131 | 28 | 165 | 94 | 18 | 18 | ||||||||

| 0 | 226 | 39.6 | 131 | 40.9 | 57 | 43.5 | 8 | 28.6 | 51 | 30.9 | 33 | 35.1 | 9 | 50.0 | 6 | 33.3 |

| 1 | 292 | 51.1 | 162 | 50.6 | 67 | 51.1 | 15 | 53.6 | 93 | 56.4 | 54 | 57.4 | 9 | 50.0 | 10 | 55.6 |

| 2 | 48 | 8.4 | 26 | 8.1 | 7 | 5.3 | 2 | 7.1 | 21 | 12.7 | 7 | 7.4 | — | — | 2 | 11.1 |

| 3 | 5 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.3 | — | — | 3 | 10.7 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Tumour stagea | 608 | 340 | 135 | 32 | 177 | 101 | 21 | 18 | ||||||||

| Binet A | 123 | 20.2 | 66 | 19.4 | 27 | 20.0 | 8 | 25.0 | 35 | 19.8 | 18 | 17.8 | 4 | 19.0 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Binet B | 218 | 35.9 | 123 | 36.2 | 61 | 45.2 | 7 | 21.9 | 63 | 35.6 | 39 | 38.6 | 11 | 52.4 | 3 | 16.7 |

| Binet C | 267 | 43.9 | 151 | 44.4 | 47 | 34.8 | 17 | 53.1 | 79 | 44.6 | 44 | 43.6 | 6 | 28.6 | 12 | 66.7 |

| Splenomegalya | 595 | 337 | 130 | 32 | 167 | 94 | 19 | 19 | ||||||||

| Presence | 374 | 62.9 | 216 | 64.1 | 80 | 61.5 | 24 | 75.0 | 91 | 54.5 | 55 | 58.5 | 8 | 42.1 | 10 | 52.6 |

| Co-morbiditiesa | 620 | 348 | 137 | 33 | 185 | 106 | 21 | 20 | ||||||||

| Presence | 429 | 69.2 | 237 | 68.1 | 85 | 62.0 | 27 | 81.8 | 135 | 73.0 | 80 | 75.5 | 10 | 47.6 | 16 | 80.0 |

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index, mean ± SD (0–34) | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 0.9 ± 1.2 | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | ||||||||

| Cardiovascular disorders | 274 | 44.2 | 147 | 42.2 | 50 | 36.5 | 19 | 57.6 | 76 | 41.1 | 44 | 41.5 | 4 | 19.0 | 10 | 50.0 |

| Diabetes | 99 | 16.0 | 53 | 15.2 | 22 | 16.1 | 10 | 30.3 | 29 | 15.7 | 12 | 11.3 | 3 | 14.3 | 6 | 30.0 |

| Renal disorders | 31 | 5.0 | 18 | 5.2 | 3 | 2.2 | 3 | 9.1 | 22 | 11.9 | 11 | 10.4 | — | — | 4 | 20.0 |

| Other tumour | 57 | 9.2 | 31 | 8.9 | 9 | 6.6 | 4 | 12.1 | 21 | 11.4 | 13 | 12.3 | 3 | 14.3 | 3 | 15.0 |

| B symptomsa | 606 | 341 | 132 | 33 | 184 | 106 | 20 | 20 | ||||||||

| Presence of B symptoms | 176 | 29.0 | 98 | 28.7 | 38 | 28.8 | 10 | 30.3 | 48 | 26.1 | 32 | 30.2 | 4 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.0 |

| Fever | 15 | 2.5 | 11 | 3.2 | 1 | 0.8 | — | — | 4 | 2.2 | 3 | 2.8 | 1 | 5.0 | — | — |

| Night sweats | 139 | 22.9 | 73 | 21.4 | 34 | 25.8 | 10 | 30.3 | 38 | 20.7 | 25 | 23.6 | 4 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.0 |

| Weight loss | 62 | 10.2 | 37 | 10.9 | 10 | 7.6 | 6 | 18.2 | 17 | 9.2 | 10 | 9.4 | — | — | 1 | 5.0 |

| Enlarged lymph node regionsa | 386 | 219 | 89 | 18 | 100 | 60 | 14 | 8 | ||||||||

| ≥3 | 256 | 66.3 | 149 | 68.0 | 68 | 76.4 | 10 | 55.6 | 67 | 67.0 | 42 | 70.0 | 12 | 85.7 | 2 | 25.0 |

B, bendamustine ± prednisone; BR, bendamustine + rituximab ± prednisone; FCR, fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab ± prednisone; BMI, body mass index; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; SD, standard deviation.

Number of patients with available data on the respective parameter at time of enrolment.

Start of therapy at enrollment.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics at the start of second-line treatment

Table 1 presents characteristics of patients at the start of second-line treatment. Fifty-seven per cent of patients are male. Patients receiving second-line treatment are 66 years at diagnosis and 73 years (range 38.4–93.7 years) at the onset of second-line treatment (median age). Most patients' clinical and laboratory parameters are comparable with those of patients at the start of first-line treatment. However, at the start of second-line treatment, patients present with slightly more co-morbidities compared with patients at the start of first-line treatment: 73% of second-line patients have at least one co-morbidity. The rate of cardiovascular disorders among this group is 41%, and 16% of patients suffer from diabetes. The rate of renal impairment is markedly higher than in the previously untreated cohort (12% vs 5%). Overall, the average Charlson Co-morbidity Index of 0.9 and the high rate of patients with ECOG 0 or 1 (87%) indicate that at the start of second-line treatment, most patients are in good general health but afflicted with more pre-existing conditions than patients at the start of first-line treatment. For further details, see Table 1.

First-line treatment

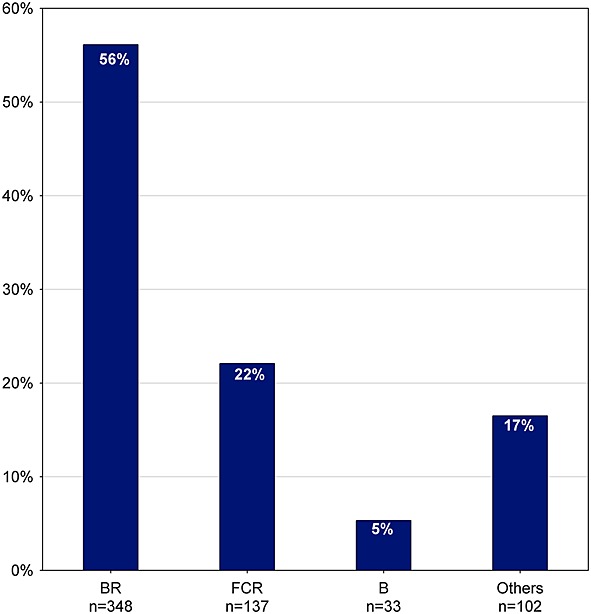

Figure 4 presents the first-line regimens most frequently used. Bendamustine + rituximab (BR) is the most common regimen, given to 56% of patients (n = 348), followed by FCR used in 22% (n = 137) and bendamustine (B) used in 5% (n = 33) of patients. The choice of treatment seems to be affected by age and clinical characteristics. Patients treated with FCR are on average younger and healthier. As shown in Table 1, these patients have a better ECOG performance status, have fewer co-morbidities, and present less often in Binet stage C disease as compared with patients treated with other first-line regimens.

Figure 4.

Frequency of first-line treatment (n = 620). B, bendamustine ± prednisone; BR, bendamustine + rituximab ± prednisone; FCR, fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab ± prednisone; others, regimens with frequency <5%

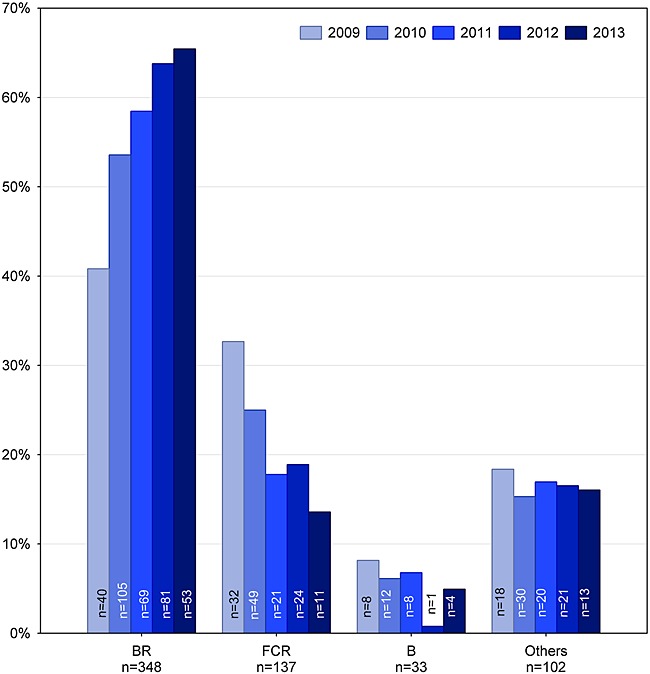

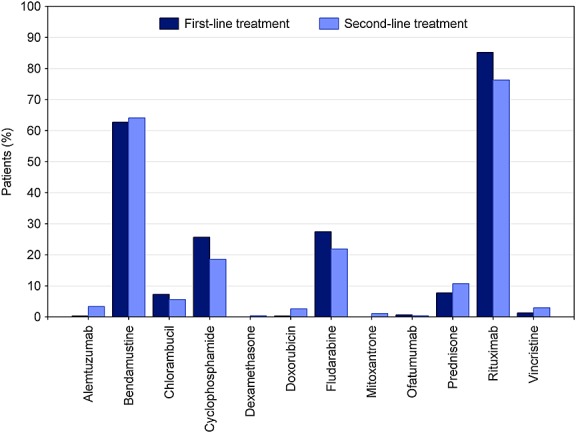

Since 2009, first-line treatment has changed considerably (Figure 5). While BR was used in 41% of patients in 2009, the rate increased to 65% in 2013. In contrast, the use of FCR decreased from 33% in 2009 to 14% in 2013. Substance use in first-line treatment is shown in Figure 6. Rituximab is used in 85% (n = 528) of all patients, bendamustine in 63% (n = 389), fludarabine in 27% (n = 170), cyclophosphamide in 26% (n = 159), prednisone in 8% (n = 48), and chlorambucil in 7% (n = 45). Chlorambucil was administered in 12% (n = 39) of patients aged 70 years and older (n = 337).

Figure 5.

Frequency of first-line treatment over time (n = 620). B, bendamustine ± prednisone; BR, bendamustine + rituximab ± prednisone; FCR, fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab ± prednisone; others, regimens with frequency <5%; n(8 months in 2009) = 98, n(12 months in 2010) = 196, n(12 months in 2011) = 118, n(12 months in 2012) = 127, n(8 months in 2013) = 81

Figure 6.

Frequency of active substances in both treatment lines (first-line treatment: n = 620, second-line treatment: n = 270)

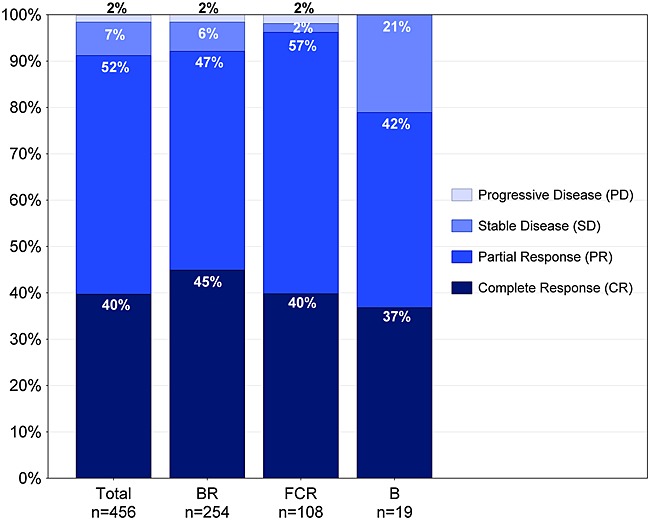

Data on best clinical response were available for 74% (n = 456) of first-line treatments (Figure 7). Overall objective response rate (ORR) was 91% (Figure 7), including 40% clinical CR and 52% partial responses (PR). Progressive disease was documented in 2% of the patients (Figure 7). In more detail, ORR for BR is 92% (n = 254; 45% CR, 47% PR), 97% for FCR (n = 108; 40% CR, 57% PR), and 79% for bendamustine B (n = 19; 37% CR, 42% PR) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Best clinical response of first-line treatment Patients with completed first-line treatment and available parameter on best clinical response. CR, clinical CR as assessed in study sites by physical examination and blood count (does usually not include marrow biopsy as recommended in clinical trials)

Second-line treatment

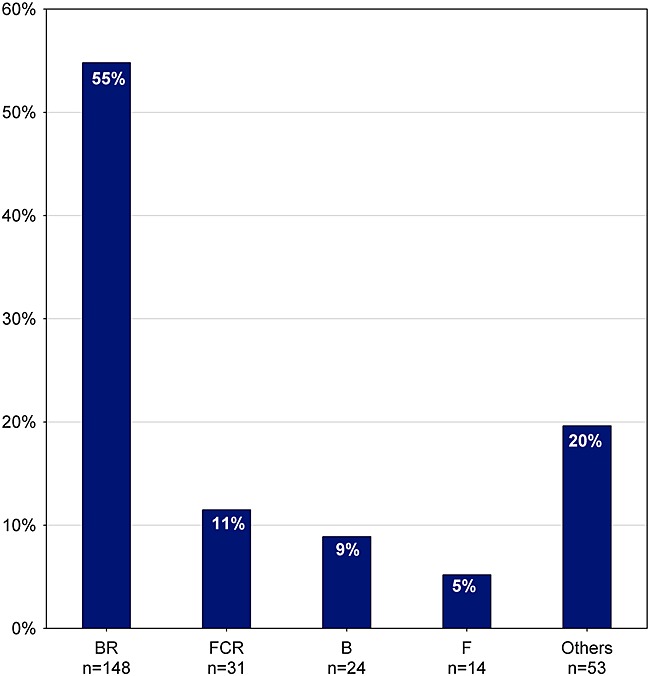

Figure 8 presents the most frequently used second-line regimens. BR is used in 55% of the patients (n = 148), followed by FCR used in 11% (n = 31) and B used in 9% (n = 24) of patients. Overall, regimens and substances used in second-line treatment are very similar to those used in first-line treatment (Figures 4 and 5). Again, choice of (second-line) treatment seems to be affected by age and clinical characteristics (Table 1). Patients treated with FCR are younger and healthier than patients treated with other regimens. Analyses on treatment changes over time are not warranted yet because of the small number of second-line treatments by then.

Figure 8.

Frequency of second-line treatment (n = 270). B, bendamustine ± prednisone; BR, bendamustine + rituximab ± prednisone; F, fludarabine; FCR, fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab ± prednisone; others, regimens with frequency <5%

Discussion

Clinical registries provide insight into real-life treatment of real-life patients. They mirror routine practice and show how the choice of treatment changes over time. Clinical registries are essential to assess the effectiveness of treatments in a real-world setting, where patients' sociodemographic and medical characteristics often differ from those of patients in RCTs. Furthermore, such registries are useful tools for post-approval drug assessments.

The TLN exclusively recruits patients in need for treatment, and thus, the characteristics of our patients differ from those of the cohort of all patients diagnosed with CLL described in epidemiological registries [2]. In the TLN, median age at diagnosis is 68 years, whereas it is 71 years for all patients with CLL in Germany [22]. Standard treatment for patients with early stage disease (Binet A and B without active disease) is active surveillance (watch-and-wait strategy) [1,5,12]. In the original series of patients that led to the establishment of the current staging system, Binet et al. found a distribution of 52–58% patients with stage A, 29–34% with stage B, and 13–14% with stage C disease [11]. The Barcelona series described a distribution of 80% patients with Binet stage A, 13% with Binet stage B, and 7% with Binet stage C disease for the 1995–2004 sample [23]. It has been estimated that approximately one third to even half of the patients will never require treatment during the course of their disease [10,11,23]. Our data show that 20% of real-life patients in need for treatment are with Binet stage A, 36% with Binet stage B, and 44% with Binet stage C disease at the start of first-line treatment.

The real-life patient population differs considerably from patients in RCTs. Median age at the start of first-line treatment is 71 years in our cohort compared with about 60–65 years in RCTs [13,14,16]. In clinical studies, the majority of patients are with Binet stage B disease [13,17,24], whereas in the TLN, most patients start first-line treatment with Binet stage C disease. Furthermore, ECOG score and number of co-morbidities indicate that the general state of health of our patients is less favourable compared with that of patients in RCTs [13,17].

These data highlight that registries can provide substantial data on the treatment of older, co-morbid, or otherwise compromised patients generally excluded from clinical trials.

Current European guidelines recommend FCR as first-line treatment for so-called fit patients with CLL, but chlorambucil or dose-reduced fludarabine and cyclophosphamide or bendamustine (either with or without rituximab) for patients with co-morbidities [1,5]. Recommendations for treatment of relapsed CLL consider the time to progression after first-line therapy. In case of late relapse (>12–24 months after monotherapy or >24–36 months after chemoimmunotherapy), the first-line treatment may be repeated, whereas treatment of early relapse should utilize new drugs or combinations different from first-line treatment [1].

The combination of BR is the predominant regimen used in our patient cohort. Since 2009, a shift from fludarabine-based to bendamustine-based regimens as the preferred first-line treatment is apparent. Recent data from phase II trials (first-line [16] and second-line [25]) indicate that BR induces high overall remission rates that compare favourably with those achievable with FCR. So, BR may also be a reliable option to treat so-called physically fit patients. The efficacy and safety of BR compared with FCR are currently under investigation in a phase III trial by the German CLL Study Group (CLL10, NCT00769522).

Of note, chlorambucil-based regimens are administered only in a small minority of patients. In general, chlorambucil does not seem to be accepted as preferred treatment in patients considered not fit enough for FCR.

A key question in clinical research is to what degree clinical efficacy shown in RCTs translates into clinical effectiveness in daily routine practice. Because of the long survival of patients with CLL, median follow-up in the TLN is yet too short to present data on progression-free or overall survival. However, data on overall response rates indicate that first-line treatments, particularly BR and FCR, seem to be highly active in real-life patients with CLL.

It is essential to consider differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in comparing outcome data between RCT and real-life patients, as well as outcome data between different groups of real-life patients. Our data reveal that multiple patient characteristics seem to affect the choice of treatment. In future analyses, the heterogeneity of our cohort may enable us to identify subgroups of patients that particularly benefit from a certain treatment. More in-depth analyses about treatment sequences and their effectiveness are ongoing within the TLN study group.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members of the TLN Study Group and all patients in the study sites for their participation in the study. Special thanks go to Martina Jänicke, Andrea Kiemen, and Victoria Smith-Machnow for their review and support with the manuscript and to Johanna Harde for updating the data of the original manuscript. The TLN Study Group collaborates with the Arbeitskreis Klinische Studien and the Kompetenznetz Maligne Lymphome.

The TLN Registry is funded by iOMEDICO. The analysis was supported by Mundipharma GmbH.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interest.

Author contributions

N. M. and W. K. conceptualized and designed the registry. R. G. coordinates the registry. W. K., R. G., and H. H. elaborated the concept for this paper, analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. M. M. did the statistical analysis and generated the figures. W. K., W. A., D. M., S. D., and N. M. recruited patients and collected and documented data. All authors reviewed and approved the submitted manuscript.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web site.

Supporting info item

References

- 1.Eichhorst BF, Dreyling M, Robak T, Montserrat E, Hallek M On behalf of the ESMO Guidelines Working Group. ESMO-guidelines chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:vi50–vi54. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koch-Institut Robert. 2012. Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V., editors. Krebs in Deutschland 2007/2008. 8. Ausgabe. Berlin.

- 3.Doll R, Payne P, Waterhouse JAH. Cancer incidence in five continents. I. Geneva, France: Union Internationale Contre le Cancer; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute. 2013. SEER stat fact sheets: chronic lymphocytic leukemia [Internet]. [cited 2013 Jan 14]; Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/clyl.html.

- 5.Wendtner CM, Dreger P, Gregor M, et al. 2012. DGHO-Leitlinie Chronische Lymphatische Leukämie (CLL) [Internet]. [cited 2012 Feb 24]. Available from: http://www.dgho-onkopedia.de/onkopedia/leitlinien/cll.

- 6.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute–Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregor M. Chronische lymphatische Leukämie—Epidemiologie, Diagnostik, prognostische Marker, Therapie. Onkologie. 2008;4:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binet JL, Caligaris-Cappio F, Catovsky D, et al. Perspectives on the use of new diagnostic tools in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:859–861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Döhner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Binet JL, Leporrier M, Dighiero G, et al. A clinical staging system for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Prognostic significance. Cancer. 1977;40:855–864. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197708)40:2<855::aid-cncr2820400239>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Binet JL, Auquier A, Dighiero G, et al. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer. 1981;48:198–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810701)48:1<198::aid-cncr2820480131>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zirlik K, Burger JA, Finke J. Das Rote Buch—Hämatologie und Internistische Onkologie. Heidelberg, Germany: ecomed Medizin; 2010. Chronische lymphatische Leukämie (CLL) pp. 648–655. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hallek M, Fischer K, Fingerle-Rowson G, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knauf WU, Lissichkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Phase III randomized study of bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4378–4384. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knauf WU, Lissitchkov T, Aldaoud A, et al. Bendamustine compared with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: updated results of a randomized phase III trial. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:67–77. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer K, Cramer P, Busch R, et al. Bendamustine in combination with rituximab for previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a multicenter phase II trial of the German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3209–3216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eichhorst BF, Busch R, Stilgenbauer S, et al. First-line therapy with fludarabine compared with chlorambucil does not result in a major benefit for elderly patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:3382–3391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-206185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schetelig J, van Biezen A, Brand R, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion: a retrospective European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5094–5100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bundesärztekammer. Tätigkeitsbericht 2011 der Bundesärztekammer [Activity report of the German medical association 2011] [Internet]. Nürnberg: 2012. Available from: http://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/downloads/Taetigkeit2011.pdf.

- 20.Berufsverband der Niedergelassenen Hämatologen und Onkologen in Deutschland (BNHO) e.V. Qualitätsbericht der onkologischen Schwerpunktpraxen 2010 [Quality report of the oncology outpatient-centers 2009] [Internet]. 2011. Available from: https://www.winho.de/fileadmin/2012/Qualitaetsbericht_2010.pdf.

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerdemann U, Pritzkuleit R, Katalinic A. Häufigkeiten [Internet]. Chronische Lymphatische Leukämie (CLL)—Onkopedia2011 [cited 2013 Feb 5]; Available from: http://www.dgho-onkopedia.de/de/onkopedia/leitlinien/cll.

- 23.Abrisqueta P, Pereira A, Rozman C, et al. Improving survival in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (1980–2008): the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona experience. Blood. 2009;114:2044–2050. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-214346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catovsky D, Richards S, Matutes E, et al. Assessment of fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (the LRF CLL4 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:230–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cramer P, Fink A-M, Busch R, et al. Second-line therapies after treatment with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) or fludarabine and cyclophosphamid alone (FC) for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) within the CLL8-protocol of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2011;118(21):2863. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting info item