Abstract

Low-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (LDPF) chemotherapy with daily radiotherapy (RT) is used as an alternative chemoradiotherapy regimen for locally advanced esophageal carcinoma. We evaluated whether RT plus LDPF chemotherapy had an advantage in terms of survival and/or toxicity over RT plus standard-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (SDPF) chemotherapy in this study. This multicenter trial included esophageal cancer patients with clinical T4 disease and/or unresectable regional lymph node metastasis. Patients were randomly assigned to receive RT (2 Gy/fraction, total dose of 60 Gy) with SDPF (arm A) or LDPF (arm B) chemotherapy. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS). A total of 142 patients (arm A/B, 71/71) from 41 institutions were enrolled between April 2004 and September 2009. The OS hazard ratio in arm B versus arm A was 1.05 (80% confidence interval, 0.78–1.41). There were no differences in toxicities in either arm. Arm B was judged as not promising for further evaluation in the phase III setting. Thus, the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee recommended that the study be terminated. In the updated analyses, median OS and 3-year OS were 13.1 months and 25.9%, respectively, for arm A and 14.4 months and 25.7%, respectively, for arm B. Daily RT plus LDPF chemotherapy did not qualify for further evaluation as a new treatment option for patients with locally advanced unresectable esophageal cancer. This study was registered at the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry as UMIN000000861.

Keywords: Chemoradiotherapy, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, randomized trial, survival, toxicity

Carcinoma of the esophagus is an extremely devastating disease, especially when the cancer is unresectable (direct invasion of adjacent organs; cT4). According to the Comprehensive Registry of Esophageal Cancer in Japan, the incidence of cT4 esophageal carcinoma is approximately 15% among all esophageal cancer patients.1 Curative resection is not feasible in patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer, particularly cT4 cancer, and such cases have an unfavorable prognosis.2–5 Definitive chemoradiotherapy (CRT) without planned esophagectomy is one of the most attractive treatment options currently available for locally advanced esophageal cancer.4–6

The combination of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is currently a standard chemotherapy for esophageal cancer. In Japan, the standard treatment regimen consists of two courses of chemotherapy with cisplatin (70 mg/m2 on days 1 and 29) and 5-FU (700 mg/m2 on days 1–4 and 29–32) administered concurrently with radiotherapy (RT). This widely used regimen is based on the results of a Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) study (JCOG9516).4 Despite a lack of sufficient evidence, RT plus low-dose cisplatin and 5-FU (LDPF) is thought to be an alternative regimen. This regimen is believed to have equivalent efficacy to RT plus standard-dose cisplatin and 5-FU (SDPF), with a low incidence of severe toxicity and the potential to permit cessation of concurrent chemotherapy before severe adverse events occur. The LDPF regimen is thought to be both a radiosensitizer and a biochemical modulator.7–9 Therefore, reports have suggested that LDPF-RT would be more effective than SDPF-RT because of biochemical modulation.

We hypothesized that LDPF-RT is more effective and less toxic than SDPF-RT in patients with locally advanced, unresectable esophageal carcinoma. Because we did not have sufficient toxicity information regarding LDPF-RT at the time this study was planned, we prepared a phase II component within the phase III trial to determine whether the phase III trial would be designed as superiority or a non-inferiority trial (based on the relative toxicities of the two arms). However, the study was terminated at the end of the phase II component; we hereby report the final results of this study.

Patients and Methods

Eligibility

Patients with histologically proven squamous cell, adenosquamous, or basaloid carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus were eligible if they had had any of the following conditions: definite clinical T4 cancer; at least 1 unresectable metastatic regional lymph node due to invasion into an adjacent organ; or computed tomography (CT) evidence of M1 lymph nodes (M1Lym), such as fixed supraclavicular or celiac lymph nodes. Regional lymph nodes were defined on the basis of criteria specified by the 5th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control TNM staging system.10 Other eligibility criteria were as follows: no prior chemotherapy and/or RT for esophageal or any other carcinoma; age 20–75 years; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) of 0–2; and sufficient organ functions. Patients with an esophageal–mediastinal, esophageal–tracheal, or esophageal–bronchial fistulae, distant organ metastases, serious complications (such as ischemic heart disease) within 3 months before registration, severe infection, or mental disorder, were excluded from the study. In addition, consultation with an institutional radiation oncologist was mandatory before enrolment to confirm that definitive radiotherapy was indicated according to the protocol.

Barium esophagography, esophagoscopy, and CT of the neck, chest, and abdomen were carried out prior to the study. Involvement of adjacent organs was determined by CT. Tumors were considered to be cT4 if they extended into the lumen or caused a deformity of the airway or if they were attached to the aorta at a contact angle of >90° in over three CT slices.11 This study protocol was approved by the JCOG Clinical Trial Review Committee and the institutional review boards of the participating institutions. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment. This study was registered with the UMIN Clinic Trials Registry (http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/), identification number UMIN000000861.

Treatment

The patients were randomized to receive either SDPF-RT (arm A) or LDPF-RT (arm B). Chemotherapy in arm A consisted of 70 mg/m2 cisplatin given on days 1 and 29 combined with a continuous infusion of 700 mg/m2 5-FU given on days 1–4 and 29–32. Arm B received a 1-h infusion of 4 mg/m2 cisplatin before RT, combined with a continuous infusion of 200 mg/m2 5-FU on the first 5 days of each week. Treatment completion was defined as termination of two courses of chemotherapy and 60 Gy radiotherapy within 63 days.

Radiotherapy using megavoltage equipment was started on day 1 concomitantly with chemotherapy in both groups. Radiotherapy was prescribed to a total dose of 60 Gy in 30 fractions, and the overall treatment period was limited to 40–63 days. For treatment planning, both conventional 2-D X-ray simulation and 3-D CT simulation were allowed. The gross tumor volume was defined as the volume of the primary tumor as indicated on CT scan and/or endoscopy and any metastatic lymph nodes measuring ≥1 cm in greatest dimension. For this trial, the clinical target volume (CTV) for the primary tumor was created to add a 2-cm margin craniocaudally to account for subclinical tumor extension. A CTV margin for metastatic lymph nodes was not added, and the CTV did not include elective irradiation of regional lymph nodes. The planning target volume was defined by adding margins to the CTV at the discretion of the treating radiation oncologists (typically 0.5–1 cm for lateral margins and 1–2 cm for craniocaudal margins, depending on respiratory motion and patient immobilization technique). A dose of 60 Gy to the center of the planning target volume was prescribed. The dose to the spinal cord was kept at ≤44 Gy. The doses to the gastric antrum, duodenum/small intestine, and colon were kept at ≤50 Gy, ≤40 Gy, and ≤45 Gy, respectively. If a tumor was located in the middle or lower thoracic esophagus, treatment using three to four ports was recommended to decrease the risk of cardiac toxicity. For the treatment of tumors in the upper thoracic esophagus and supraclavicular lymph node metastases, the number of ports used was left to the discretion of the radiation oncologists.

Assessment

Toxicities were monitored weekly during treatment according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 2.0). Late toxicity was graded according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer late radiation morbidity scoring scheme. Late toxicity was defined as toxicity occurring more than 31 days after treatment completion.

Primary tumor response was evaluated by endoscopy using the modified criteria of the Japanese Society for Esophageal Diseases. Complete response (CR) was defined when both primary tumors and lymph node metastases disappeared without the presence of ulceration or malignant cells in biopsy specimens at the first evaluation after CRT. Patients with CR were followed without treatment on the basis of post-treatment evaluation. If recurrence was noted after treatment, surgical resection was considered if possible.

Radiotherapy quality assurance review was carried out in this study, and the results have been reported elsewhere.12

Statistical methods

The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS), and the secondary endpoints were the proportion of CR (%CR), the proportion of treatment completion by PS, and toxicity. After confirmation of eligibility criteria, patients were randomly assigned to either arm A (SDPF-RT) or arm B (LDPF-RT) at the JCOG Data Center. A minimization method was used to balance clinical T status (cT4 vs cT1–3), PS (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 0 vs 1 vs 2), and institution.

This study was designed as an adaptive phase II/III trial in which the purpose of the phase II component was to evaluate for futility and to determine the study design of the phase III component. If arm B (LDPF-RT) was inferior to arm A (SDPF-RT) with a one-sided significance level of 0.1 in the phase II component, this study was to be terminated due to futility. In addition, the toxicities of both arms were evaluated at the conclusion of the phase II component. The phase III component was to be a superiority trial if arm B was proven to be more toxic than arm A in the phase II component, whereas it was to be a non-inferiority trial if arm B was less toxic than arm A.

The planned sample size in the phase II component was 110 or more to detect a hazard ratio of 1.6 with a one-sided alpha of 0.1 and power of at least 0.85. Assuming a non-inferiority design at the planning of this study, the planned sample size in phase III was 364 patients (including phase II patients) with a power of 80%, a one-sided alpha of 5%, an expected 1-year OS of 40%, and a non-inferiority margin of 1.31 for the hazard ratio. The planned accrual was 4 years, and the follow-up period was 1 year. Overall survival was calculated from the date of randomization to the date of death from any cause and was censored at the time of last follow-up. Overall survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and comparisons between the two arms were carried out using the unstratified log–rank test. Hazard ratios of treatment effects were estimated by using the unstratified Cox regression model. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software, release 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient randomization

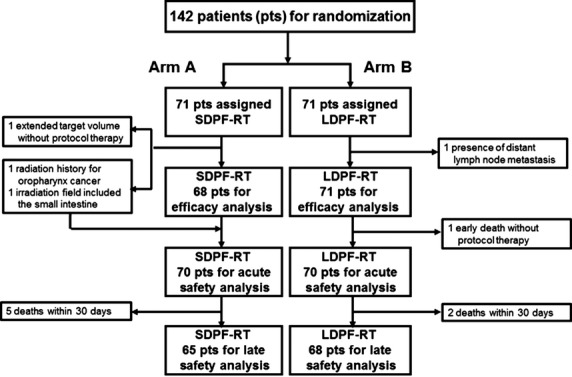

A CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure1. Initially, this study included 25 institutions. Ultimately, the number of institutions was increased to 41. During the period between April 2004 and September 2009, a total of 142 patients were registered. The median number of patients who were registered in each institution was 2 (range, 0–17). The median observation time of all patients and survivors were 13.6 and 54.7 months, respectively. Three of 71 patients in arm A were ineligible. The reasons for ineligibility were: history of radiation for oropharynx carcinoma, extended target volume, and irradiation fields that included the small intestine. Eventually, a total of 139 patients were eligible and were included in the efficacy analysis; the safety analysis was conducted for 140 treated patients, excluding two untreated patients (one in each arm).

Fig 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of a multicenter phase II trial of radiotherapy (2 Gy/fraction, total dose of 60 Gy) and standard-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (SDPF-RT; arm A) or low-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (LDPF-RT; arm B) chemotherapy in esophageal cancer patients with clinical T4 disease and/or unresectable regional lymph node metastasis.

Patient characteristics

The baseline characteristics of each arm are shown in Table1. Histopathological findings from biopsy specimens of all patients indicated squamous cell carcinoma. These patients consisted of 1% (142/14 111) of all patients with thoracic esophageal carcinoma treated in the participating institutions during the study. Thirty-one percent (142/464) of all patients who met the eligibility criteria agreed to participate in this study. The characteristics of patients in both treatment arms were similar.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with unresectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (all randomized; n = 142)

| Arm A (n = 71) | Arm B (n = 71) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median (range) | 63 (37–75) | 62 (43–74) |

| Sex | ||

| Male/female | 67/4 | 61/10 |

| PS (ECOG) | ||

| 0 | 35 | 35 |

| 1 | 35 | 35 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Location† | ||

| Upper | 19 | 21 |

| Middle | 50 | 46 |

| Lower | 2 | 4 |

| cTNM (UICC) | ||

| T | ||

| T1 | 2 | 0 |

| T2 | 6 | 2 |

| T3 | 11 | 13 |

| T4 | 52 | 56 |

| N | ||

| N0 | 10 | 10 |

| N1 | 61 | 61 |

| M | ||

| M0 | 41 | 42 |

| M1a | 11 | 14 |

| M1b | 19 | 15 |

| cStage (UICC) | ||

| IIB | 3 | 1 |

| III | 38 | 41 |

| IVA | 11 | 14 |

| IVB | 19 | 15 |

Lower, lower thoracic esophageal cancer; Middle, middle thoracic esophageal cancer; Upper, upper thoracic esophageal cancer. ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PS, performance status; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control.

Treatment completion

Fifty-six of 68 patients (82%) in arm A and 61 of 71 patients (86%) in arm B completed treatment. The reasons for treatment termination in arm A and arm B included tumor progression (2/3), adverse events (8/3), patient refusal associated with adverse events (0/2), death during treatment (2/1), and other reasons (0/1). The proportion of treatment completion by PS was as follows: PS0 74% (26/35) and 89% (31/35), PS1 91% (29/32) and 86% (30/35), and PS2 100% (1/1) and 0% (0/1) in arm A and arm B, respectively. As a post-therapy, 20 patients (12 in group A and 8 in group B) underwent surgery for residual or recurrent disease.

Toxicity

Toxicities that occurred during treatment among the 70 treated patients in each arm are listed in Table2. The proportion of grade 3 or 4 hematological toxicities in arm A and arm B included leukopenia (26/21%), neutropenia (19/7%), anemia (14/6%), thrombocytopenia (4/3%), and hyponatremia (17/13%). Other grade 4 hematological adverse events included elevation of AST (n = 1), elevation of ALT (n = 2), hypernatremia (n = 1), and hyperkalemia (n = 1) in arm A and hypokalemia (n = 1) in arm B. The proportion of most common grade 3–4 non-hematological toxicities in arm A and arm B included included dysphasia/esophagitis/odynophagia (23/29%), anorexia (20/21%), infection without neutropenia (9/13%), and fistula formation (9/7%).

Table 2.

Proportion of grade 3–4 toxicities during treatment of patients with unresectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with radiotherapy and standard-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (arm A) or low-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (arm B)

| Arm A (n = 70), n (%) | Arm B (n = 70), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic adverse events | ||

| Leukopenia | 18 (26) | 15 (21) |

| Neutropenia | 13 (19) | 5 (7) |

| Anemia | 10 (14) | 4 (6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Non-hematologic adverse events | ||

| Dysphagia/esophagitis/odynophagia | 16 (23) | 20 (29) |

| Anorexia | 14 (20) | 15 (21) |

| Nausea | 6 (9) | 2 (3) |

| Vomiting | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Hyponatremia | 12 (17) | 9 (13) |

| Infection without neutropenia | 6 (9) | 9 (13) |

| Infection with neutropenia | 4 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Fistula formation | 6 (9) | 5 (7) |

Grade 3–4 late toxicities that occurred 30 days after completion of treatment in 65 and 68 assessable patients in arm A and arm B, respectively, included fistula formation (18/22), dysphasia/esophagitis/odynophagia (11/10), dyspnea (14/18), pneumonitis (9/9), and pericardial effusion (3/0) (all percentages), as shown in Table3.

Table 3.

Proportion of grade 3–4 late toxicities in patients with unresectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with radiotherapy and standard-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (arm A) or low-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (arm B)

| Arm A (n = 65), n (%) | Arm B (n = 68), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fistula formation | 12 (18) | 15 (22) |

| Dysphasia/esophagitis/odynophagia | 7 (11) | 7 (10) |

| Dyspnea | 9 (14) | 12 (18) |

| Pneumonitis | 6 (9) | 6 (9) |

| Pericarditis | 2 (3) | 0 (0) |

Grade 3–4 fistula formation occurred frequently in both arms, affecting 15 patients in arm A and 17 patients in arm B. In total, fistula formation occurred in 32 of 140 patients (23%) during or after treatment. Thirteen patients in each arm had cT4 disease before treatment. Intercurrent deaths occurred in two patients in arm A and one patient in arm B. The causes of death in arm A were massive bleeding precipitated by an esophageal–aortic fistula and pneumonia due to an esophageal–pulmonary fistula. In arm B, the single intercurrent death was caused by massive bleeding due to an esophageal–tracheal fistula.

Before the analysis of the phase II component, the participating investigators, while remaining blinded to the efficacy data for each arm, discussed the advantages and disadvantages of both arms and concluded that both arms were equally toxic but that arm B (RT plus LDPF) had disadvantages that included a longer time spent receiving continuous infusion chemotherapy and longer hospital stays. Thus, they declared to the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee that the phase III component should be a superiority trial of arm B over arm A.

Efficacy

In May 2009, the OS among patients receiving LDPF-RT was slightly inferior to patients treated with SDPF-RT (hazard ratio, 1.05; 80% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–1.41; unstratified one-sided log-rank P for non-inferiority =0.42). Eventually, the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee of JCOG recommended that the study be terminated due to futility rather than moved forward to the phase III component. The study was therefore terminated after the phase II component was completed.

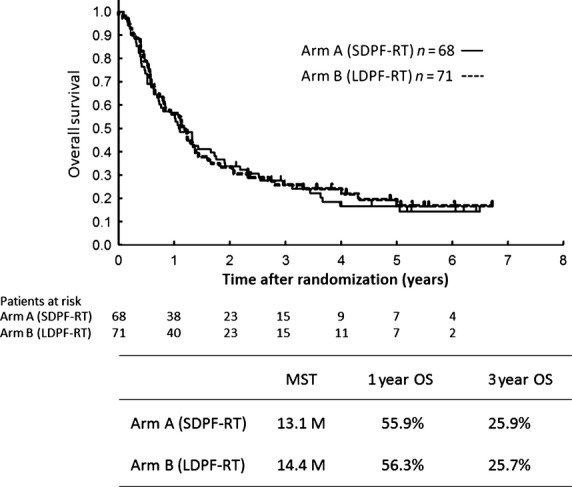

In the updated analyses in November 2011, none of the 68 patients in arm A achieved CR, whereas of the 71 patients in arm B, 1 attained CR (%CR, 1.4%). The 1- and 3-year OS rates were 55.9% and 25.9% in arm A and 56.3% and 25.7%, respectively, in arm B. The median survival time was 13.1 months for arm A and 14.4 months for arm B. Arm B was not superior to arm A in terms of OS (hazard ratio, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.64–1.37; Fig.2).

Fig 2.

Overall survival (OS) of 139 eligible patients with esophageal cancer with clinical T4 disease and/or unresectable regional lymph node metastasis treated with radiotherapy (2 Gy/fraction, total dose of 60 Gy) and standard-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (SDPF-RT; arm A) or low-dose cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (LDPF-RT; arm B). M, months; MST, median survival time.

Discussion

We carried out a randomized phase II study that compared LDPF-RT (arm B) with SDPF-RT (arm A) for patients with cT4 or M1Lym esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Enrolment of patients was planned to continue as phase III if arm B showed advantages in efficacy and/or toxicity over arm A in the randomized phase II. However, findings revealed that LDPF-RT had no advantage over SDPF-RT in terms of efficacy or toxicity, and this study was terminated in the phase II component.

Although SDPF-RT has been the standard treatment regimen with modest toxicities for esophageal cancer, a less toxic regimen is preferred for more advanced stage cT4 disease.13–15 In Japan, LDPF-RT is believed to be less toxic and more effective, despite insufficient supporting evidence,16–23 because LDPF has a theoretical radiosensitizing effect and low toxicity. Moreover, should adverse effects occur, LDPF can be stopped immediately. Because of these perceived advantages, LDPF has begun to prevail in Japan as a treatment for esophageal cancer. Therefore, this study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of LDPF-RT in patients with locally advanced, unresectable esophageal cancer.

Our study showed that the primary endpoint of OS was nearly equivalent in both treatment arms. Therefore, our results suggest that LDPF-RT had no survival advantage over SDPF-RT. The 2-year OS of 33.6% in the 139 eligible patients in this study was close to the 2-year OS (31.5%) reported in our previous study (JCOG9516) of SDPF.4 Similarly, the 3-year OS of 25.9% in the 139 eligible patients in this study was roughly equivalent to the 3-year OS (approximately 23%) reported by other studies.6,24,25 We noted that the treatment completion rate was slightly higher in arm B (86%) than in arm A (82%); we speculated that this difference in completion rate might have been due to the difference in the total dose of cisplatin, which was slightly lower in arm B (120 mg/m2) than in arm A (140 mg/m2).

The CR rate in this study was markedly lower than the rate reported in previous studies;6,24,25 however, OS was equivalent between the two treatment arms. JCOG9516 was a phase II trial of SDPF-RT (the same protocol as arm A in this study) in patients with cT4 or M1Lym advanced esophageal cancer4 and demonstrated relatively low %CR (15%) with an acceptable 2-year survival (31.5%), fairly similar to the rates reported in the present study. In contrast to the JCOG trials (this study and JCOG9516), another trial conducted in Japan by Ohtsu et al.6 reported a higher %CR (33%) and a nearly equivalent 3-year survival (23%) compared to the current study. The discrepancy between the JCOG trials and other trials might be due to differences in the definitions of CR among these studies.

Regarding toxicity, in this study, LDPF-RT was not associated with decreased toxicity compared with SDPF-RT. Although the incidence of hematological toxicity during treatment was low in arm B, there were no significant differences in the incidences of either non-hematological toxicity or late toxicities. Finally, there was no significant difference in the incidence of fistula formation between the two arms. These findings show that LDPF-RT had no advantage over SDPF-RT in terms of efficacy and toxicity.

Fistula formation is associated with massive bleeding and pneumonia and can be the primary cause of treatment-related death. In this study, esophageal fistulae developed in 15 (21%) of the 70 treated patients in arm A and 17 (24%) of the 70 treated patients in arm B. This incidence was relatively high compared to incidences of 9–29% reported in other studies6,26–28 involving patients with similar stages of esophageal cancer. There are two possible explanations for this high rate of fistula formation. First, data regarding delayed toxicities, including disease progression, were prospectively collected for our secondary endpoints. Second, cT4 cancer was defined as a tumor that invades adjacent organs and is technically impossible to resect curatively.

Similar to our findings, Sai et al.29 also concluded that daily low-dose cisplatin with a continuous infusion of 5-FU had no advantage over standard-dose cisplatin with 5-FU in terms of survival, local control, or toxicity. Furthermore, Nishimura et al.27 maintained that LDPF-RT might have curative potential, but that this regimen had high toxicity for patients with cT4 esophageal cancer. Although a certain level of toxicity inevitably occurs during and after cancer treatment, a large number of treatment-related deaths is not acceptable. Results from KROSG0101, a randomized phase II trial comparing LDPF-RT to SDPF-RT regimens in clinical stage II–IVA esophageal cancer patients, also showed that LDPF-RT was not superior to the SDPF-RT regimen.30 The 2- and 5-year overall survival rates for SDPF-RT were 46% and 35% (95% CI, 22–48%), whereas those for LDPF-RT were 44% and 22% (95% CI, 11–35%), respectively. Toxicity was similar in both arms. This means that the efficacy of the PF-RT regimen is similar in efficacy and toxicity irrespective of a method.

Another difficulty with LDPF-RT was that all patients in arm B required hospitalization at least until the end of the treatment period because they were receiving continuous infusions of cisplatin and 5-FU. However, 19 (27%) of the 70 patients in arm A could be treated in the outpatient clinic, except for the period when they received chemotherapy in the hospital.

In summary, on the basis of this study, we conclude that the conventional treatment regimen for locally advanced, unresectable esophageal cancer should be considered the standard treatment. Although LDPF-RT prevails in Japan, we have not been able to identify an obvious advantage for this CRT regimen over the SDPF-RT regimen in terms of efficacy, compliance, or toxicity. Therefore, the development of more effective and safe CRT regimens is necessary.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the JCOG Data Center/Operations Office for their support: Ms. Aya Kimura, Ms. Hiromi Katsuki, and Ms. Chikako Aibara for data management; Mr. Taro Shibata and Junki Mizusawa for statistical analysis; and Dr. Hiroshi Katayama for medical writing. This study was supported by a Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant for Clinical Research for Evidence-Based Medicine (H14-35), a Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant for Clinical Cancer Research (H17-33), and Grants-in-Aid for Cancer Research (14S-3, 14S-4, 17S-3, 17S-5, 20S-3, and 20S-6) from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan. This study was also supported by National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds (23-A-16, 23-A-18, and 26-A-4).

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Comprehensive Registry of Esophageal Cancer in Japan (1998, 1999) & Long-Term Results of Esophagectomy in Japan (1988–1997. 3rd edn. Tokyo: The Japanese Society for Esophageal Diseases; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara T, Ueda M, Kokubo N, et al. Role of esophagectomy in treatment of esophageal carcinoma with clinical evidence of adjacent organ invasion. World J Surg. 2001;25:279–84. doi: 10.1007/s002680020060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Ishida K, Sato N, et al. Chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for thoracic esophageal cancer potentially or actually involving adjacent organs. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14:197–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2001.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida K, Ando N, Yamamoto S, et al. Phase II study of cisplatin and 5- fluorouracil with concurrent radiotherapy in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a Japan Esophageal Oncology Group(JEOG)/Japan Clinical Oncology Group Trial(JCOG 9516) Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:615–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H, Sueyoshi S, Tanaka T, et al. Esophagectomy: is it necessary after chemoradiotherapy for a locally advanced T4 esophageal cancer? Prospective nonrandomized trial comparing chemoradiotherapy with surgery versus without surgery. World J Surg. 2005;29:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7590-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsu A, Boku N, Muro K, et al. Definitive chemoradiotherapy for T4 and /or M1 lymph node squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2915–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon KJ, Newman EM, Lu Y, et al. Biochemical basis for cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil synergism in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8923–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano G, Troger V, Courdi A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of cisplatin given at a daily low dose as a radiosensitiser. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1990;27:55–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00689277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byfield JE. Combined modality infusing chemotherapy with radiation. In: Lokich JJ, editor. Cancer Chemothrapy by Infusion. 2nd edn. Chicago, IL: Percepta Press; 1990. pp. 521–51. [Google Scholar]

- UICC. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 5th edn. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Picus D, Balfe DM, Kochler RE, et al. Computed tomography in the staging of esophageal carcinoma. Radiology. 1983;146:433–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.146.2.6849089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanuki N, Ishikura S, Shinoda M, et al. Radiotherapy quality assurance review for a multi-center randomized trial of locally advanced esophageal cancer: the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) trial 0303. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012;17:105–11. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikura S, Ohtsu A, Shirao K, et al. A phase I/II study of nedaplatin and 5-fluorouracil with concurrent radiotherapy in patients with T4 esophageal cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial (JCOG9908) Esophagus. 2005;2:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- Herskovic A, Martz K, Al-Sarraf M, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1593–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206113262403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sarraf M, Martz K, Herskovic A, et al. Progress report of combined chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:277–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Harskamp G, Boven E, Vermorken JB, et al. Phase II trial of combined radiotherapy and daily low-dose cisplatin for inoperable, locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13:1735–8. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaake-Koning C, Maat B, van Houtte P, et al. Radiotherapy combined with low-dose cis-diamimine dichloroplatinum (II) (CDDP) in inoperable nonmetastatic non- small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a randomized three arm phase II study of the EORTC lung cancer and radiotherapy cooperative groups. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 1990;19:967–72. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90020-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerbroek NA, Fossella FV, Rich TA, et al. Low-dose continuous infusion cisplatin combined with external beam irradiation for advanced colorectal adenocarcinoma and unresectable non-small cell lung carcinoma. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 1991;20:351–5. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90119-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazuka MB, Crowley JJ, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Daily low-dose cisplatin plus concurrent high-dose thoracic irradiation in locally advanced unresectable non-small cell lung: Results of a phase II Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1814–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.9.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KN, Rotman M, Aziz H, et al. Locally advanced paranasal sinus and nasopharynx tumors treated with hyperfractionated radiation and concomitant infusion cisplatin. Cancer. 1991;67:2748–52. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910601)67:11<2748::aid-cncr2820671106>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeremic B, Shibamoto Y, Milicic B, et al. Hyperfractionated radiation therapy with or without concurrent low-dose cisplatin in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1458–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki K, Inakoshi H, Sueyama H, et al. Concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy with protracted continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil in inoperable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 1995;31:921–7. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raoul JL, Prise EL, Meunier B, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and hyperfractionated radiotherapy with concurrent low-dose chemotherapy for squamous cell esophageal carcinoma. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 1998;42:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasamoto R, Sakai K, Inakoshi H, et al. Long-term results of chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced esophageal cancer, using low-dose 5-fluorouracil and cis-diammine-dichloroplatinum (CDDP) Int J Clin Oncol. 2007;12:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s10147-006-0617-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagawa R, Kunisaki C, Makino H, et al. Efficacy of chemoradiothrapy with low-dose cisplatin and continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil for unresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:482–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko K, Inakoshi H, Konishi K, et al. Definitive chemoradiotherapy for patients with malignant stricture due to T3 or T4 squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:18–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Suzuki M, Nakamatsu K, et al. Prospective trial of concurrent chemoradiotherapy with protracted infusion of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for T4 esophageal cancer with or without fistula. Int J Radiation Oncology Biol Phys. 2002;53:134–9. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel A, Cheze S, Jacob JF, et al. Radiation therapy in esophageal carcinoma with broncho-tracheal involvement (BTI): The Center Francois Baclesse (CFB) experience. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1995;14:191a. abstr438. [Google Scholar]

- Sai H, Mitsumori M, Yamauchi C, et al. Concurrent chemoraditherapy for esophageal cancer: comparison between intermittent standard dose cisplatin with 5-fluorouracil and daily low dose cisplatin with continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004;9:149–53. doi: 10.1007/s10147-004-0385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura Y, Hiraoka M, Koike R, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized Phase II study of cisplatin/5-FU concurrent chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer (KROSG0101/JROSG021) Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:807–12. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]