Abstract

Purpose

To compare the self-reported symptoms between IC/BPS and OAB based on patient-reported symptoms on validated questionnaires.

Materials and Methods

Patients diagnosed with IC/BPS (n=26) or OAB (n=53), and healthy controls (n=30), were prospectively recruited to participate in a questionnaire-based study that inquired their lower urinary tract symptoms using the following questionnaires: 1) Genitourinary pain index, 2) Interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index, 3) International consultation on incontinence – overactive bladder, 4) International consultation on incontinence – urinary incontinence short form (ICIQ-UI), 5) Urgency severity scale, 6) numeric rating scales (NRS) of the severity of their bladder “pain, pressure, or discomfort”, and 7) NRS of severity of their urgency and 8) frequency symptoms.

Results

In univariate analyses, IC/BPS patients reported significantly more severe pain symptoms compared to OAB. OAB patients reported significantly more severe urinary incontinence symptoms compared to IC/BPS. There were no differences in the severity of frequency and urgency between IC/BPS and OAB. Surprisingly, 33% of OAB patients reported pain or discomfort when the bladder filled, while 46% of IC/BPS patients reported urgency incontinence. In multivariate analyses, the total scores on the ICIQ-UI Short Form (p=0.01) and the severity (NRS) of bladder pain (p<0.01) distinguished OAB from IC/BPS with a sensitivity of 90.6% and a specificity of 96.1% (OAB has higher ICIQ-UI and lower pain scores on NRS).

Conclusions

There is considerable overlap of self-reported symptoms between IC/BPS and OAB. This overlap raises the possibility that IC/BPS and OAB represent a continuum of a bladder hypersensitivity syndrome.

Introduction

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and overactive bladder (OAB) are clinical syndromes defined primarily by patient-reported symptoms.1, 2 It is generally believed that IC/BPS and OAB can be distinguished based on patient-reported symptoms. Urgency incontinence is considered unusual in IC/BPS while bladder pain is rare in OAB. A concept paper argued that there should be no confusion in distinguishing the two conditions.3 The authors associated urgency and urgency incontinence with OAB, and of frequency/nocturia and bladder pain with IC/BPS. However, clinical observation suggest that there might be some overlap between the two conditions.4, 5 Some IC/BPS patients present with frequency and urgency without pain,6–8 while some OAB patients do not have detrusor overactivity.9

Recent studies have specifically compared the “urgency” symptoms of IC/BPS and OAB.10, 11 These studies showed that OAB patients associated urgency to the fear of incontinence, while IC/BPS patients reported urgency due to pain, pressure, or discomfort. However, there was significant overlap, and the authors concluded that “urgency” could not be used to clearly distinguish OAB from IC/BPS.11

With respect to the broader lower urinary tract symptoms, the degree of overlap and distinction between IC/BPS and OAB remains to be formally defined. How common are bladder pain, pressure or discomfort in OAB patients? How often do IC/BPS patients have incontinence? Does the severity of frequency and urgency differ between the two conditions? Specifically we would like to know whether the two conditions might be distinguished based on self-reported symptoms on validated questionnaires with high sensitivity and specificity. Without definitive diagnostic tests or biomarkers, clinicians rely primarily on patient-reported symptoms to make the clinical diagnosis and treatment decisions. Distinguishing between the two conditions is important since the management strategies differ.2, 12

Materials and Methods

Population

Patients with a diagnosis of IC/BPS or OAB were consented and enrolled by a single clinician (HHL) between October 2012 and March 2014. Data were collected prospectively from the validated questionnaires completed by the patients. Briefly, the enrollment criteria for the IC/BPS patients required an unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than 6 weeks duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes (2011 AUA Guideline).2 For OAB patients, complain of urinary urgency, with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia (2002 ICS definition), and in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes.1 The clinical assessment conformed to the published AUA guidelines.2, 12 Healthy volunteers (controls) were recruited by local advertisement and research database. Controls had no prior diagnosis of OAB or IC/BPS, no significant lower urinary tract symptoms (AUA symptom index less than 7), and no significant bladder or pelvic pain, and no evidence of infection. 26 IC/BPS patients, 53 OAB patients, and 30 healthy controls consented to participate in the study (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics, and univariate comparison of symptoms in the pain, frequency, urgency, and incontinence domains.

| Controls | OAB | IC/BPS | p-value (IC/BPS vs. OAB, univariate) | Comparing the pain symptoms between OAB and controls; comparing UI between IC/BPS and controls | p-value*** (odds ratio of being in the OAB group instead of IC/BPS, 95% CI, multivariate model) | Individual question on the questionnaire | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients (n) | 30 | 53 | 26 | - | |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 54.2 ± 12.3 | 54.2 ± 11.3 | 44.1 ± 16.6 | 0.005* | p=0.10 (OR=1.07, CI=0.99–1.16) | ||

| Sex, n (%) Female | 17 (56.7%) | 35 (73.6%) | 26 (100%) | 0.003* | |||

|

| |||||||

| Pain symptoms: | p-value** (OAB vs. controls, univariate) | ||||||

| Rate the severity of pain, pressure, or discomfort associated with the bladder and/or pelvic region (NRS 0–10) | 0.20 ± 0.48 | 2.69 ± 2.54 | 6.23 ± 2.37 | <0.001* | <0.001 | Numeric rating scale, 0 to 10 | |

| Rate the pain associated with your bladder (NRS 0–10) | 0 ± 0 | 1.98 ± 2.58 | 6.62 ± 2.12 | <0.001* | <0.001 | p<0.01* (OR 0.29, CI=0.13–0.63) | Numeric rating scale |

| Rate the pressure associated with your bladder (NRS 0–10) | 0.07 ± 0.25 | 3.38 ± 2.88 | 6.00 ± 2.51 | <0.001* | <0.001 | Numeric rating scale | |

| Rate the discomfort associated with your bladder (NRS 0–10) | 0.10 ± 0.31 | 3.63 ± 2.98 | 6.58 ± 2.27 | <0.001* | <0.001 | Numeric rating scale | |

| Have you experienced pain or burning in your bladder? (0–5) | 0.07 ± 0.37 | 0.83 ± 1.35 | 3.44 ± 1.47 | <0.001* | 0.004 | ICSI question 4 | |

| How much has burning, pain, pressure, discomfort in your bladder been a problem? (0–4) | 0.03 ± 0.18 | 1.09 ± 1.53 | 3.24 ± 1.01 | <0.001* | <0.001 | ICPI question 4 | |

| GUPI pain sub-score (0–23) | 0.21 ± 0.79 | 6.1 ± 6.5 | 13.9 ± 4.77 | <0.001* | <0.001 | GUPI pain sub-scale | |

|

| |||||||

| Frequency symptoms: | |||||||

| Rate the severity of your frequency of urination (0–10) | 0.59 ± 0.87 | 6.53 ± 2.66 | 6.23 ± 2.37 | 0.576 | Numeric rating scale | ||

| Have you had to urinate less than 2 hours after you finished urinating? (0–5) | 0.43 ± 0.68 | 3.44 ± 1.34 | 3.48 ± 1.58 | 0.757 | ICSI question 2 | ||

| How often have you most typically get up at night to urinate (0–5) | 1.5 ± 1.43 | 3.04 ± 1.30 | 2.64 ± 1.47 | 0.216 | ICSI question 3 | ||

| How much has frequent urination during the day been a problem for you (0–4) | 0.13 ± 0.35 | 2.89 ± 1.18 | 2.6 ± 1.35 | 0.414 | ICPI question 1 | ||

| How much has getting up at night been a problem for you (0–4) | 0.53 ± 0.68 | 2.98 ± 1.20 | 2.40 ± 1.32 | 0.068 | p=0.40 (OR=0.66, CI=0.25–1.76) | ICPI question 2 | |

| GUPI urinary sub-score (0–10) | 0.73 ± 1.31 | 5.30 ± 2.92 | 5.60 ± 2.75 | 0.702 | GUPI urinary sub-scale | ||

|

| |||||||

| Urgency symptoms: | |||||||

| Rate the severity of your urgency symptoms (0–10) | 0.37 ± 0.61 | 6.32 ± 2.63 | 5.96 ± 2.88 | 0.705 | Numeric rating scale | ||

| How often have you felt the strong need to urinate with little or no warning? (0–5) | 0.17 ± 0.38 | 2.83 ± 1.70 | 2.80 ± 1.73 | 0.922 | ICSI question 1 | ||

| How much has the need to urinate with little warning been a problem for you? (0–4) | 0.10 ± 0.31 | 2.74 ± 1.24 | 2.04 ± 1.37 | 0.037* | p=0.30 (OR=1.59, CI=0.65–3.91) | ICPI question 3 | |

| Urgency severity scale (0–3) | 0.52 ± 0.57 | 2.07 ± 0.73 | 1.96 ± 0.81 | 0.662 | IUSS | ||

|

| |||||||

| Incontinence symptoms: | p-value** (IC/BPS vs. controls, univariate) | ||||||

| How often do you leak urine? (0–5) | 0.30 ± 0.47 | 3.23 ± 1.38 | 1.62 ± 1.55 | <0.001* | <0.001 | ICIQ-UI question 3 | |

| How much urine do you usually leak? (0–6) | 0.60 ± 0.93 | 2.83 ± 1.49 | 1.77 ± 1.42 | 0.006* | 0.001 | ICIQ-UI question 4 | |

| How much does leaking urine interfere with your daily life? (0–10) | 0.35 ± 0.63 | 6.38 ± 3.10 | 2.96 ± 3.09 | <0.001* | <0.001 | ICIQ-UI question 5 | |

| ICIQ-UI Short Form total score (0–21) | 1.38 ± 1.98 | 12.4 ± 4.9 | 6.3 ± 5.7 | <0.001* | <0.001 | p=0.01* (OR=1.68, CI=1.13–2.50) | |

|

| |||||||

| Total scores on questionnaires: | |||||||

| GUPI total score (0–45) | 1.80 ± 2.77 | 18.9 ± 10.9 | 27.4 ± 9.3 | 0.005* | |||

| ICSI total score (0–20) | 2.17 ± 1.98 | 10.2 ± 3.7 | 12.4 ± 5.0 | 0.077 | |||

| ICPI total score (0–16) | 0.80 ± 1.00 | 9.7 ± 3.4 | 10.3 ± 4.1 | 0.550 | |||

| ICIQ-OAB (0–16) | 2.03 ± 1.54 | 9.3 ± 2.7 | 7.3 ± 4.2 | 0.029* | |||

NRS = numeric rating scale, 0 to 10. Mean ± SD. OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval.

Statistical significance (p<0.05).

The pain symptoms were compared between OAB and controls. The incontinence symptoms were compared between IC/BPS and controls. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used.

The final multivariate model was chosen as the most informative model using exactly one variable representative of each of the four symptom categories of interest (pain, frequency, urgency, and incontinence) as well as a covariate of interest (age).

Assessment

All participants completed the following validated questionnaires: 1) Genitourinary pain index (GUPI)13, 2) Interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index (ICSI, ICPI)14, 3) International consultation on incontinence modular questionnaire – overactive bladder (ICIQ-OAB)15, 4) International consultation on incontinence modular questionnaire – urinary incontinence short form (ICIQ-UI)16, 5) Urgency severity scale (IUSS) to assess the severity of urgency symptoms17, 6) numeric rating scales (NRS, 0 to 10) of the severity of “pain, pressure, or discomfort” in the bladder or pelvic region, and 7) NRS (0 to 10) of the severity of their urgency symptoms, and 8) frequency symptoms. All participants signed an informed consent. The Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Statistical Analyses

Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare survey results from IC/BPS, OAB and controls. p<0.05 was considered significant. Missing data was ignored for the univariate results.

There were 324 omitted answers out of 5609 possible for the variables of interest (5.8%). Multivariate imputation was used on the missing data for the multivariate analysis. The number of imputations was set to 10. Multivariate logistic regression was used on the imputed datasets with diagnosis type (OAB or IC) as the response variable. Because of the large number of variables available and high correlation between many of those variables, many models were examined using a variety of combinations of independent variables. The final most informative multivariate model chosen used exactly one variable representative of each of the four symptom categories of interest (pain, frequency, urgency, and incontinence) as well as a covariate of interest (age). The variables that showed statistical significance in the final model had no omitted answers. All statistical analysis was completed in the statistical package R v2.15.1 primarily using the package MICE for multivariate imputation and analysis.18

Results

In univariate analyses (see Table 1), the pain symptoms of OAB were significantly less than those of IC/BPS (p<0.001), but they were worse than those of healthy controls. The incontinence symptoms of IC/BPS were significantly less than those of OAB (p≤0.006), but they were worse than those of healthy controls. There were no differences in the severity of frequency and urgency symptoms between IC/BPS and OAB (both higher than controls).

With respect to the composite scores on validated questionnaires, IC/BPS patients had higher total scores on the GUPI (Genitourinary pain index, p=0.005), and lower total scores on the ICIQ-UI (p<0.001) and on the ICIQ-OAB (p=0.029) compared to OAB patients. There were no differences in the total scores on the ICSI, ICPI, or IUSS between IC/BPS and OAB.

Because of the surprising report of pain in OAB patients and incontinence in IC/BPS patients, we examined their responses on the GUPI and ICIQ-UI questionnaires in greater details. 33% of OAB patients reported pain or discomfort when the bladder fills (one of hallmark features of IC/BPS, see Table 2). 28% of OAB patients reported their pain or discomfort was reduced by urination. 25% of OAB patients reported pain or burning during urination. 28% of OAB patients reported pain below their waist, in the suprapubic and bladder area. As shown in Table 3, 69% of IC/BPS patients reported some incontinence in the past four weeks: 46% had urgency incontinence while >42% had stress incontinence.

Table 2.

Types of pelvic pain (self-reported) based on responses on the GUPI Questionnaire.

| Types of pelvic pain (GUPI Questionnaire): | OAB | IC/BPS | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Pain or burning during urination | 25.0% | 77.8% | 0.0002* |

| Pain or discomfort during or after sexual intercourse | 16.3% | 60.0% | 0.0023* |

| Pain or discomfort as your bladder fill | 32.6% | 73.3% | 0.0050* |

| Pain or discomfort reduced by voiding | 27.9% | 78.9% | 0.0003* |

|

| |||

| Location of pain or discomfort: | |||

|

| |||

| 1) Urethra | 16.3% | 68.0% | <0.001* |

| 2) Below you waist, in your pubic or bladder area | 27.9% | 96.0% | <0.001* |

| 3) Entrance to vagina [females only] | 21.2% | 50.0% | 0.023* |

| 4) Vagina [females only] | 13.8% | 60.9% | <0.001* |

| 5) Area between rectum and testicles, in the perineum [males only] | 7.7% | No males | N/A |

| 6) Testicles [males only] | 7.7% | No males | N/A |

Chi-square tests of independence or Fisher’s exact test.

Statistical significance

Table 3.

Types of incontinence (self-reported) based on responses on the ICIQ-UI Questionnaire.

| Types of incontinence (ICIQ-UI Questionnaire): | OAB | IC/BPS | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Never – does not leak | 1.9% | 30.8% | <0.001* |

| Leaks before you can get to the bathroom | 75.5% | 46.2% | 0.010* |

| Leaks when you cough or sneeze | 41.5% | 42.3% | 0.946 |

| Leaks when you are asleep | 17.0% | 3.8% | 0.153 |

| Leaks when you are physically active/exercise | 35.8% | 38.5 | 0.821 |

| Leaks when you have finished urinating and are dressed | 37.7% | 15.4% | 0.067 |

| Leaks for no obvious reasons | 24.5% | 11.5% | 0.239 |

| Leaks all the time | 5.7% | 7.7% | 1.000 |

Statistical significance.

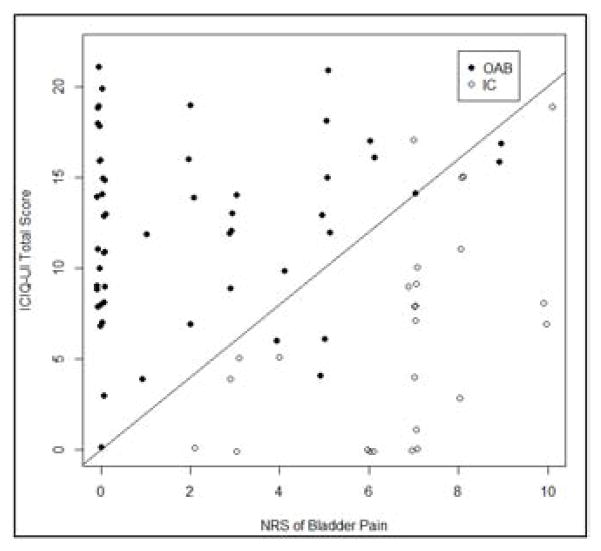

In multivariate analyses (Table 1), OAB patients reported significantly higher total scores on the ICIQ-UI (p=0.01) and less severe bladder pain on the NRS (p<0.01) compared to IC/BPS patients. When we plotted the numeric rating scale (NRS) of bladder pain (0 to 10) on the x-axis, the ICIQ-UI Short Form total score (0 to 21) on the y-axis, and drew a straight line with a slope of two as shown in Figure 1, the IC/BPS and OAB groups separated roughly across this line. Responses on ICIQ-UI Short Form and the severity (NRS) of bladder pain distinguished OAB from IC/BPS with a sensitivity of 90.6% and a specificity of 96.1%.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of the distribution of OAB and IC/BPS patients. A hypothetical line with a slope of 2 was drawn in the scatterplot for reference. (X-axis = NRS of bladder pain symptoms 0 to 10, Y-axis = ICIQ-UI Short Form total score 0 to 21, solid circle = OAB, open circle = IC/BPS). Sensitivity of OAB = 90.6% and specificity = 96.1%.

Discussion

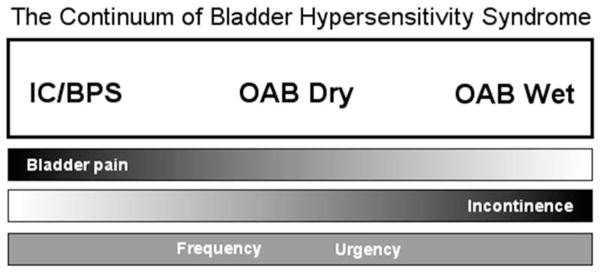

It is generally believed that pain is the distinguishing feature of IC/BPS while urgency and urgency incontinence are the hallmark feature of OAB.3 However, we think this distinction is far from absolute but rather it represents a continuum of a bladder hypersensitivity syndrome. Our data showed that the pain symptoms of OAB were intermediate between IC/BPS and controls, while the incontinence symptoms of IC/BPS were intermediate between OAB and controls. Up to one-third of our OAB patients (~33%) reported symptoms that are classically associated with IC/BPS (e.g. pain with bladder filling, pain reduced by urination, pain in the bladder area), while close to half of IC/BPS patients (~46%) reported urgency incontinence. While we anticipated some overlap between the two conditions, this high degree of overlap of self-reported symptoms is very surprising to us. Our conceptual model is depicted in Figure 2. On one end of the continuum is “OAB Wet” characterized by urgency incontinence, and on the other end is “IC/BPS” characterized by bladder pain, and in-between we have varying degree of frequency and urgency (leaning towards IC/BPS with frequency, and towards “OAB Dry” with urgency).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the overlap and distinction between IC/BPS and OAB.

While a single lower urinary tract symptom (like pain or incontinence alone) may not reliably distinguish IC/BPS from OAB, using a combination of pain scores and incontinence scores may distinguish the two conditions. In the multivariate analyses, ICIQ-UI and NRS bladder pain scores remained significantly different between IC/BPS and OAB. Patients with high incontinence and low pain scores are more likely to have OAB. This concept is illustrated in Figure 1, which plotted the ICIQ-UI total scores against the NRS pain scores. A line with a slope of two distinguished OAB from IC/BPS with high sensitivity and specificity (90.6% and 96.1%, respectively). Since this calculation was based on 79 subjects, a formal validation study using larger number of participants should be conducted in the future to validate the findings.

The incontinence finding in IC/BPS is germane. Clinically, one cannot rule out IC/BPS if incontinence is present. IC/BPS patients tend to structure their lives to be close to bathroom at all times, and generally make it to a bathroom with strong urgency. However, if for practical reason they cannot find a bathroom quickly, and the bladder becomes distended and the pain reaches an intolerable level (pain increases with distention19), some IC/BPS patients may voluntarily pass a small amount of urine to reduce the distention and to ease the pain temporarily, so they have drops of urinary incontinence on the way to bathroom. This type of incontinence may be different from the classic urge incontinence of OAB (large gush of urine with an involuntary bladder contraction). Unfortunately, our validated instruments cannot discern this difference, but we suspected this might explain some of the overlap. Another potential cause for urgency incontinence in IC/BPS patients may be due to urethral instability. Since up to 80% have high tone pelvic floor dysfunction20 that can manifest as urethral instability during urodynamic studies, spontaneous relaxation with urgency and urgency incontinence can be seen. Of note, >42% of IC/BPS patients also have stress incontinence.

The phraseology “pain, pressure, or discomfort” is commonly used to describe IC/BPS.2, 21 When we de-constructed the phrase “pain, pressure, or discomfort” into its three discrete descriptors and asked the questions separately (“pain”, “pressure”, “discomfort”), significant differences were noted in all three descriptors in univariate analyses. However, in multivariate analyses, only the response to the bladder “pain” question remained statistically significant (p<0.01). Bladder “pain” is the discriminative descriptor of IC/BPS, while reference to bladder “pressure” or “discomfort” appears to be less specific. It is conceivable that the sudden “urgency” in OAB may be considered “discomfort” or “pressure” by some patients. From patients’ perspective, the distinction between “urgency”, “urge”, “pressure”, and “discomfort” is not always clear and may vary among individuals. All of these can be considered a continuum of noxious urinary sensation.

Nevertheless, the observation of pain complaints in OAB patients is intriguing. MacDiarmid and Sand suggested that women with detrusor overactivity and good sphincter function may be able to voluntarily contract their pelvic muscle during an involuntary bladder contraction to prevent incontinence, but this habitual pelvic floor overactivity may cause pain from high pressure detrusor contractions against a closed outlet.5 Another possible explanation is the clinical presentation of IC/BPS can be quite variable and may evolve over time. At the time of presentation, only 7% of IC/BPS patients will describe the entire spectrum of symptoms that they will ultimately develop.7 42% of IC/BPS women reported frequency as the only prodromal symptom, that was, they specifically denied any bladder pain, pressure, discomfort or pelvic pain prior to the onset of IC/BPS.22 IC/BPS patients may initially present with frequency/urgency symptoms and are assigned a working diagnosis of OAB. Patients with milder form of IC/BPS may report intermittent or mild discomfort or pressure, instead of characterizing it as pain. However, they may later progress to have pain.6–8 In the current study, we did not have any IC/BPS patients who reported no pain. However, in a previous Interstitial Cystitis Data Base (ICDB) cohort study in which pain was not an absolute entry criteria, 10% of patients with a clinical diagnosis of IC/BPS did not report pain.23

It would be difficult to distinguish IC/BPS and OAB based on urgency and frequency symptoms since: 1) they are present in both conditions, 2) their severity are similar [as shown in this study], and 3) their descriptors overlapped. Clemens et al showed that 42% of OAB patients reported urgency due to “pain, pressure, or discomfort”, while 11% of IC/BPS patients associated urgency to the fear of incontinence.11 Greenberg et al reported that 21% of IC/BPS cases associated urgency to prevent incontinence.10 Kim et al compared the objective response on 3-day voiding diaries between IC/BPS and OAB, and showed a difference in night-time frequency but not in day-time frequency.24

There are several potential explanations of the considerable overlap of lower urinary tract symptoms between IC/BPS and OAB. One possibility is that OAB and IC/BPS represent truly different conditions, and patients in the gray zone simply have both conditions. It is also possible that during a short clinical encounter, both the patient and the clinician are so focused on the chief complaints that the full spectrum of other symptoms has not been solicited. There is a risk of diagnostic error particularly for syndromes like IC/BPS and OAB where there are no definitive diagnostic tests or biomarkers, and the diagnosis is assigned primarily based on patient-reported symptoms. In academic research centers like ours that tend to attract larger volume of IC/BPS patients and “refractory OAB cases”, it is possible that refractory “OAB Dry” patients may be mislabeled and actually have IC/BPS. There is evidence in the literature of mislabeling IC/BPS patients as having OAB.25 Therefore it is critically important to reassess the working diagnosis if patients fail conventional treatments. In “refractory OAB” cases, the diagnosis of IC/BPS should be considered, since some “refractory OAB patients” may respond to IC/BPS treatments.5, 26

Based on our data, it is distinctly possible that “OAB Wet”, “OAB Dry”, and IC/BPS might represent a continuum of a bladder hypersensitivity syndrome as previously described (see Figure 2). From a mechanistic point of view, it is possible that IC/BPS and OAB share common pathophysiological processes, molecular or genetic markers, giving rise to the continuum.

This report has several strengths: 1) validated questionnaires were used uniformly to all three patient groups, and 2) it compared broader urinary storage symptoms besides “urgency”. Potential weaknesses of this study include: 1) the smaller number of participants, even though many of the comparisons have reached significance, 2) most of the OAB patients had urinary incontinence (weighed heavily towards “OAB Wet”), 3) the reliance of ICIQ questionnaire modules to assess incontinence (instead of using other instruments such as the UDI-6 and IIQ-7), and 4) the need for further validation of the construct presented in Figure 1.

Conclusions

There is considerable overlap of lower urinary tract symptoms between IC/BPS and OAB. The overlap raises the possibility that IC/BPS and OAB represent a continuum of a bladder hypersensitivity syndrome. Ultimately we need comparative mechanistic studies of IC/BPS and OAB to understand how the two syndromes are similar and different. Results from the current study called for a re-thinking of the relationship between symptom clusters and presumptive clinical diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

The study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers P20-DK-097798 and K08-DK-094964. The study was conducted as a part of the Washington University Biorepository and Informatics Grid for Benign Urological Diseases (BIGBUD) project. We would like to thank Aleksandra Klim and Vivien Gardner to recruit participants into the study, Mary Hoffmann for assistance with regulatory approvals, and Alathea Paradis for data management.

Abbreviations

- GUPI

genitourinary pain index

- IC/BPS

interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome

- ICIQ-UI

International consultation on incontinence – urinary incontinence

- ICSI

interstitial cystitis symptom index

- ICPI

interstitial cystitis problem index

- IUSS

Urgency severity scale

- NRS

numeric rating scale

- OAB

overactive bladder

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:116. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.125704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. AUA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. J Urol. 2011;185:2162. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams P, Hanno P, Wein A. Overactive bladder and painful bladder syndrome: there need not be confusion. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:149. doi: 10.1002/nau.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott CS, Payne CK. Interstitial cystitis and the overlap with overactive bladder. Curr Urol Rep. 2012;13:319. doi: 10.1007/s11934-012-0264-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macdiarmid SA, Sand PK. Diagnosis of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome in patients with overactive bladder symptoms. Rev Urol. 2007;9:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porru D, Politano R, Gerardini M, et al. Different clinical presentation of interstitial cystitis syndrome. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15:198. doi: 10.1007/s00192-004-1129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166:2118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons CL. Interstitial cystitis: epidemiology and clinical presentation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:242. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200203000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SH, Kim TB, Kim SW, et al. Urodynamic findings of the painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: a comparison with idiopathic overactive bladder. J Urol. 2009;181:2550. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenberg P, Brown J, Yates T, et al. Voiding urges perceived by patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27:287. doi: 10.1002/nau.20516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemens JQ, Bogart LM, Liu K, et al. Perceptions of “urgency” in women with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome or overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:402. doi: 10.1002/nau.20974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188:2455. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clemens JQ, Calhoun EA, Litwin MS, et al. Validation of a modified National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index to assess genitourinary pain in both men and women. Urology. 2009;74:983. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49:58. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson S, Donovan J, Brookes S, et al. The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire: development and psychometric testing. Br J Urol. 1996;77:805. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, et al. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2004;23:322. doi: 10.1002/nau.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nixon A, Colman S, Sabounjian L, et al. A validated patient reported measure of urinary urgency severity in overactive bladder for use in clinical trials. J Urol. 2005;174:604. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165461.38088.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Multivariate Imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45:1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren JW, Langenberg P, Greenberg P, et al. Sites of pain from interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2008;180:1373. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters KM, Carrico DJ, Kalinowski SE, et al. Prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction in patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2007;70:16. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van de Merwe JP, Nordling J, Bouchelouche P, et al. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. Eur Urol. 2008;53:60. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren JW, Wesselmann U, Greenberg P, et al. Urinary Symptoms as a Prodrome of Bladder Pain Syndrome/Interstitial Cystitis. Urology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Propert KJ, Schaeffer AJ, Brensinger CM, et al. A prospective study of interstitial cystitis: results of longitudinal followup of the interstitial cystitis data base cohort. The Interstitial Cystitis Data Base Study Group. J Urol. 2000;163:1434. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SH, Oh SA, Oh SJ. Voiding diary might serve as a useful tool to understand differences between bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis and overactive bladder. Int J Urol. 2014;21:179. doi: 10.1111/iju.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parsons CL. The role of a leaky epithelium and potassium in the generation of bladder symptoms in interstitial cystitis/overactive bladder, urethral syndrome, prostatitis and gynaecological chronic pelvic pain. BJU Int. 2011;107:370. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung MK, Butrick CW, Chung CW. The overlap of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome and overactive bladder. JSLS. 2010;14:83. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12674612014743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]