Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between diabetes and premature death for Japanese general people.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

The Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study (JPHC study), data collected between 1990 and 2010.

Population

A total of 46 017 men and 53 567 women, aged 40–69 years at the beginning of baseline survey.

Main outcome measures

Overall and cause specific mortality. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate the HRs of all cause and cause specific mortality associated with diabetes.

Results

The median follow-up period was 17.8 years. During the follow-up period, 8223 men and 4640 women have died. Diabetes was associated with increased risk of death (856 men and 345 women; HR 1.60, (95% CI 1.49 to 1.71) for men and 1.98 (95% CI 1.77 to 2.21) for women). As for the cause of death, diabetes was associated with increased risk of death by circulatory diseases (HR 1.76 (95% CI 1.53 to 2.02) for men and 2.49 (95% CI 2.06 to 3.01) for women) while its association with the risk of cancer death was moderate (HR 1.25 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.42) for men and 1.04 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.32) for women). Diabetes was also associated with increased risk of death for ‘non-cancer, non-circulatory system disease’ (HR 1.91 (95% CI 1.71 to 2.14) for men and 2.67 (95% CI 2.25 to 3.17) for women).

Conclusions

Diabetes was associated with increased risk of death, especially the risk of death by circulatory diseases.

Keywords: DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large scale population-based prospective study, the study population was defined as all registered Japanese inhabitants in the 11 public health centre areas, was conducted.

In Japan, the registration of deaths is required by the Family Registration Law and is believed to be complete.

The assessment of diabetes mellitus was based on a self-report. Although the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosed diabetes were reported to be high, the assessment of diabetes by self-report is most likely an underestimate.

The association between mortality and glycaemia was not examined because data about glycaemia were not available for the entire population.

Introduction

Today, Japanese people, especially Japanese women, are one of the people who live longest in the world.1 On the other hand, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes has increased over the past few decades in Japan and the total number of patients with diabetes is estimated to have risen from 7.4 million in 2002 to 9.5 million in 2012.2 Diabetes is an important cause of mortality and morbidity and there are many literatures concerning the association between diabetes and mortality. However, most of these literatures were focused on the Western people and the impact of diabetes on premature death among Japanese people was not well examined. Several genetic and environmental differences as well as causes of death between Japanese and Western people exist and in the present study we examined the association between diagnosed diabetes and premature death for Japanese general people in a large scale population-based cohort study.

Methods

The Japan Public Health Centre-based prospective study (JPHC study) consists of two cohort, Cohort I and Cohort II that comprise five and six prefectural public health centre areas, respectively. The JPHC Study group members are listed in online supplementary appendix. The study population was defined as all registered Japanese inhabitants in the 11 public health centre areas, aged 40–69 years at the beginning of each baseline survey, that is, in 1990 for Cohort I and in 1993 for Cohort II. Details of the study design have been described elsewhere.3 The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the National Cancer Centre.

Initially, 140 420 participants were identified as the study population. Participants with non-Japanese nationality, duplicate enrolment, late report of emigration occurring before the start of follow-up or ineligibility because of incorrect birth date (n=260) were excluded.

Questionnaire

At the baseline survey, each participant completed a self-administered questionnaire that included questions about various lifestyle factors; such as medical history of major diseases, smoking and alcohol drinking status, height and weight and leisure-time physical activity. A similar survey was conducted at 5 and 10 years after the baseline survey.

At baseline, a total of 113 402 participants responded to the questionnaire (response rate 80.9%). Participants whose follow-up period was not determined were excluded from further analysis (n=90). Participants with any of the following conditions at baseline: cardiovascular disease, chronic liver disease, kidney disease and any type of cancer, were also excluded (n=8049). Participants who had missing baseline data for any of the exposure parameters described below (in Statistical Analysis; n=5049) or participants with a body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres) of less than 14 or more than 40 (n=1363) were also excluded, because body mass index less than 14 or more than 40 in Japanese implies potentially unreliable data. After the above exclusions, the remaining cohort consisted of 99 584 participants (46 017 men and 53 567 women).

Assessment of diabetes

We defined the participant as having diagnosed diabetes if he or she marked on ‘diabetes mellitus’ to the question ‘Has a doctor ever told you that you have any of the following diseases?’ or on ‘anti-diabetic drug’ to the question ‘Do you take any of the following drugs?’ The sensitivity and specificity of diagnosed diabetes was reported as 82.9% and 99.7%, respectively.4 The questionnaire did not distinguish type 1 and type 2 diabetes. However, the participants of the present study were Japanese inhabitants aged 40–69 years and we believe that most of the participants with diagnosed diabetes had type 2 diabetes.

Follow-up

Participants were followed from the baseline survey up to 31 December 2010. All death certificates were forwarded centrally to the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Labor and coded for the National Vital Statistics. In Japan, the registration of deaths is required by the Family Registration Law and is believed to be complete. The underlying cause of death was determined by death certificates and was coded according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10). Until 1995, the cause of death was determined according to the criteria of the ICD-9 and from 1995, the codes were translated into the corresponding ICD-10 codes.

Statistical analysis

Person-years of follow-up were counted from the date of the baseline survey until one of the following end points: the date of emigration from Japan, the date of death or the end of the study period (31 December 2010), whichever comes first. Age-standardised mortality rate was calculated by direct method using 5-year age-specific mortality rate and the total population (participants with and without diabetes) as standard. The association between diabetes and premature death was estimated as HRs using Cox's proportional hazards model with age as the time scale.5 We adjusted potential confounding factors: body mass index (categorised as 14–18.4, 18.5–24.9, 25–29.9 and 30–40), alcohol intake (categorised by weekly ethanol intake as non-drinker, 1–149 g/week, 150–299 g/week, 300–449 g/week and ≥450 g/week for men and the last two categories were combined into a category ≥300 g/week for women), smoking status (categorised as never smoker, past smoker, current smoker at <20 and ≥20 cigarettes per day), leisure-time physical activity (dichotomised as participate in sports at least once a week or not) and history of hypertension. The public health center areas were included in the analysis as strata. Effect of birth cohort was also examined by including birth cohort (birth year of 1920–1929, 1930–1939 and 1940–). Difference of the association between diabetes and mortality by diagnosed period was also examined by including information about diagnosis of diabetes at 5 and 10-year survey for participants who responded to 5 and/or 10-year survey, that is, participants were classified into four groups according to the period of diagnosis of diabetes: diagnosed before baseline, diagnosed between baseline and 5-year survey, diagnosed between 5 and 10-year survey, never diagnosed. Person-years of follow-up of participants diagnosed between baseline and 5-year survey and diagnosed between 5 and 10-year survey were counted from 5 and 10 years after the baseline survey, respectively.

HRs were calculated for death from all cause, circulatory system diseases (ICD-10, I00-I99), all cancer (ICD-10, C00-C97) and site-specific cancer if there were five or more cases in participants with diabetes. Deaths from other than circulatory system disease or cancer were grouped as ‘non-cancer, non-circulatory system disease’ and the HR for this group was also calculated. The proportional hazards assumption was checked graphically and by using Schoenfeld residuals.

All analyses were performed separately for men and women.

Results

The median follow-up period was 17.8 years both for men and women. During the follow-up period, 8223 men and 4640 women have died. The baseline characteristics of the study participants are shown in table 1. At baseline, 6% of men and 2.8% of women had diagnosed diabetes. Among men, age, proportion of participants with leisure-time physical activity and history of hypertension were higher among participants with diabetes. Among women, age, the body mass index, proportion of participants with leisure-time physical activity and history of hypertension were higher among participants with diabetes. Besides these factors, medication about hypercholesterolaemia was higher among participants with diabetes (3.5% among men with diabetes and 1.2% among men without diabetes for and 5.5% among women with diabetes and 1.9% among women without diabetes).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to diagnosed diabetes

| Men (n=46 017) |

Women (n=53 567) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM(−) (n=43 256) |

DM(+) (n=2761) |

DM(−) (n=52 042) |

DM(+) (n=1525) |

|||||

| Age | 50 | (44–56) | 53 | (49–59) | 50 | (44–57) | 56 | (50–62) |

| BMI | 23.5 | (2.8) | 23.7 | (3.0) | 23.3 | (3.1) | 24.4 | (3.6) |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Never | 10 175 | (23.5) | 577 | (20.9) | 47 347 | (91.0) | 1363 | (89.4) |

| Past | 10 106 | (23.4) | 713 | (25.8) | 942 | (1.8) | 45 | (3.0) |

| Current (<20 cigarettes/day) | 5913 | (13.7) | 398 | (14.4) | 2422 | (4.7) | 64 | (4.2) |

| Current (≥20 cigarettes/day) | 17 062 | (39.4) | 1073 | (38.9) | 1331 | (2.6) | 53 | (3.5) |

| Alcohol | ||||||||

| Non-drinker | 13 248 | (30.6) | 944 | (34.2) | 44 844 | (86.2) | 1386 | (90.9) |

| 1–150 g/week | 9667 | (22.4) | 575 | (20.8) | 5609 | (10.8) | 103 | (6.8) |

| 150–300 g/week | 9032 | (20.9) | 511 | (18.5) | 996 | (1.9) | 16 | (1.0) |

| 300–450 g/week (≥300 week for women) | 5325 | (12.3) | 273 | (9.9) | 593 | (1.1) | 20 | (1.3) |

| ≥450 g/week | 5984 | (13.8) | 458 | (16.6) | ||||

| Physical activity (active) | 8188 | (18.9) | 682 | (24.7) | 9629 | (18.5) | 381 | (25.0) |

| Hypertension (+) | 7218 | (16.7) | 795 | (28.8) | 8145 | (15.7) | 545 | (35.7) |

DM, diabetes mellitus.

Among men without diabetes, 1744 participants died from circulatory system disease, 3093 participants died from cancer and 2530 participants died from other causes, while among men with diabetes, these numbers were 230, 283 and 343, respectively. Among women without diabetes, 1084 participants died from circulatory system disease, 1841 participants died from cancer and 1370 participants died from other causes, while among women with diabetes, these numbers were 123, 71 and 151, respectively.

HRs for major causes of death were shown in table 2. As shown in table 2, diabetes was associated with increased risk of death both for men and women. The HR was high for circulatory system disease (ischaemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease) among men and especially high for ischaemic heart disease and cerebral infarction among women. The association between diabetes and the risk of death from cancer was moderate and the HRs were not high except some types of cancer (liver cancer both among men and women and pancreas, kidney and bladder cancer among men), while death from ‘multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms’ in men and ‘malignant neoplasm of breast’ in women was markedly lower among participants with diabetes (46/0 cases for multiple myeloma and 135/1 cases for neoplasm of breast). Diabetes was also associated with increased risk of death for ‘non-cancer, non-circulatory system disease’. These results were almost unchanged when the deaths during the first 5 years were excluded. The major causes of death for ‘non-cancer, non-circulatory system disease’ among participants with diabetes were ‘unspecified diabetes mellitus’ (E14) (men 17.8%, women 22.5%), ‘pneumonia, organism unspecified’ (J18) (men 13.7%, women 13.9%) and ‘unknown causes’ (men 6.4%, women 10.6%).

Table 2.

Mortality according to diagnosed diabetes

| Men | DM(−) (n=43 256) | DM(+) (n=2761) | HR |

Excluding cases during first 5 years |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Rate* | Cases | Rate* | Crude |

Multivariate-adjusted* |

Multivariate-adjusted* HR |

||||

| All-cause | 7367 | 98.0 | 856 | 163.9 | 1.65 | (1.54–1.77) | 1.60 | (1.49–1.71) | 1.59 | (1.47–1.71) |

| All circulatory system diseases (ICD-10:I00-I99) | 1744 | 23.2 | 230 | 43.6 | 1.88 | (1.63–2.15) | 1.76 | (1.53–2.02) | 1.79 | (1.54–2.09) |

| Ischaemic heart disease (ICD-10:I20-I25) | 434 | 5.8 | 76 | 14.2 | 2.47 | (1.93–3.15) | 2.30 | (1.80–2.95) | 2.32 | (1.78–3.03) |

| Cerebrovascular disease (ICD-10:I60-I69) | 705 | 9.4 | 88 | 16.7 | 1.78 | (1.43–2.23) | 1.68 | (1.34–2.10) | 1.75 | (1.37–2.23) |

| Cerebral infarction (ICD-10:I63) | 176 | 2.3 | 27 | 4.9 | 2.07 | (1.38–3.11) | 1.87 | (1.24–2.82) | 1.76 | (1.09–2.82) |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage (ICD-10:I61) | 227 | 3.0 | 27 | 5.6 | 1.86 | (1.25–2.78) | 1.73 | (1.16–2.59) | 2.00 | (1.30–3.07) |

| All-cancer (ICD-10:C00-C97) | 3093 | 41.2 | 283 | 53.6 | 1.28 | (1.13–1.45) | 1.25 | (1.11–1.42) | 1.22 | (1.06–1.39) |

| All sites excluding the liver | 2850 | 37.9 | 244 | 46.0 | 1.20 | (1.05–1.37) | 1.18 | (1.03–1.34) | 1.16 | (1.00–1.34) |

| All sites excluding the liver and pancreas | 2652 | 35.3 | 216 | 40.5 | 1.14 | (0.99–1.31) | 1.12 | (0.97–1.29) | 1.11 | (0.95–1.29) |

| Oesophagus (ICD-10:C15) | 171 | 2.3 | 16 | 3.0 | 1.35 | (0.80–2.25) | 1.31 | (0.78–2.20) | 1.01 | (0.53–1.93) |

| Stomach (ICD-10:C16) | 543 | 7.2 | 37 | 7.2 | 0.95 | (0.68–1.32) | 0.92 | (0.66–1.29) | 0.73 | (0.49–1.11) |

| Colon (ICD-10:C18) | 172 | 2.3 | 19 | 3.6 | 1.62 | (1.01–2.61) | 1.61 | (1.00–2.60) | 1.73 | (1.04–2.87) |

| Rectum (ICD-10:C19-C21) | 146 | 1.9 | 12 | 2.3 | 1.20 | (0.66–2.16) | 1.17 | (0.65–2.12) | 1.29 | (0.67–2.47) |

| Liver (ICD-10:C22) | 243 | 3.2 | 39 | 7.6 | 2.20 | (1.57–3.10) | 2.12 | (1.50–2.98) | 1.89 | (1.27–2.80) |

| Bile duct (ICD-10:C23-C24) | 133 | 1.8 | 17 | 3.1 | 1.78 | (1.07–2.96) | 1.76 | (1.06–2.92) | 1.68 | (0.96–2.94) |

| Pancreas (ICD-10:C25) | 198 | 2.6 | 28 | 5.4 | 1.98 | (1.33–2.95) | 1.95 | (1.31–2.91) | 1.80 | (1.15–2.81) |

| Lung (ICD-10:C33-C34) | 778 | 10.4 | 49 | 9.1 | 0.85 | (0.64–1.14) | 0.84 | (0.63–1.13) | 0.87 | (0.64–1.19) |

| Kidney (ICD-10:C64-C66, C68) | 51 | 0.7 | 10 | 2.1 | 2.75 | (1.39–5.43) | 2.50 | (1.26–4.98) | 2.32 | (1.09–4.98) |

| Bladder (ICD-10:C67) | 39 | 0.5 | 10 | 1.8 | 3.38 | (1.68–6.81) | 3.29 | (1.63–6.65) | 3.63 | (1.78–7.39) |

| Prostate (ICD-10:C61) | 107 | 1.4 | 10 | 1.7 | 1.29 | (0.67–2.47) | 1.24 | (0.65–2.39) | 1.31 | (0.68–2.53) |

| Non-cancer, non-circulatory system disease | 2530 | 33.6 | 343 | 66.7 | 1.96 | (1.75–2.19) | 1.91 | (1.71–2.14) | 1.90 | (1.67–2.15) |

| Women | (n=52 042) |

(n=1525) |

||||||||

| All-cause | 4295 | 45.9 | 345 | 102.3 | 2.11 | (1.89–2.35) | 1.98 | (1.77–2.21) | 2.02 | (1.79–2.28) |

| All circulatory system diseases (ICD-10:I00-I99) | 1084 | 11.6 | 123 | 36.6 | 2.82 | (2.33–3.40) | 2.49 | (2.06–3.01) | 2.56 | (2.09–3.13) |

| Ischaemic heart disease (ICD-10:I20-I25) | 196 | 2.1 | 42 | 13.4 | 5.10 | (3.64–7.13) | 4.52 | (3.21–6.37) | 4.56 | (3.17–6.57) |

| Cerebrovascular disease (ICD-10:I60-I69) | 479 | 5.1 | 38 | 11.3 | 2.08 | (1.49–2.90) | 1.72 | (1.23–2.40) | 1.72 | (1.19–2.47) |

| Cerebral infarction (ICD-10:I63) | 98 | 1.1 | 18 | 5.5 | 4.31 | (2.60–7.15) | 3.43 | (2.05–5.74) | 3.61 | (2.12–6.15) |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage (ICD-10:I61) | 136 | 1.5 | 9 | 3.2 | 1.93 | (0.98–3.81) | 1.64 | (0.83–3.24) | 1.71 | (0.83–3.54) |

| All-cancer (ICD-10:C00-C97) | 1841 | 19.6 | 71 | 22.6 | 1.08 | (0.85–1.37) | 1.04 | (0.82–1.32) | 1.05 | (0.81–1.36) |

| All sites excluding the liver | 1730 | 18.4 | 61 | 19.9 | 1.00 | (0.77–1.29) | 0.96 | (0.74–1.24) | 0.93 | (0.70–1.24) |

| All sites excluding the liver and pancreas | 1540 | 16.4 | 52 | 17.3 | 0.97 | (0.73–1.27) | 0.93 | (0.71–1.23) | 0.90 | (0.66–1.23) |

| Stomach (ICD-10:C16) | 224 | 2.4 | 8 | 3.4 | 1.05 | (0.52–2.13) | 1.10 | (0.54–2.24) | 1.21 | (0.57–2.60) |

| Colon (ICD-10:C18) | 160 | 1.7 | 5 | 1.7 | 0.84 | (0.35–2.06) | 0.81 | (0.33–2.00) | 0.79 | (0.29–2.15) |

| Liver (ICD-10:C22) | 111 | 1.2 | 10 | 2.6 | 2.30 | (1.20–4.40) | 2.21 | (1.15–4.27) | 2.66 | (1.37–5.17) |

| Pancreas (ICD-10:C25) | 190 | 2 | 9 | 2.6 | 1.22 | (0.62–2.39) | 1.10 | (0.56–2.16) | 1.17 | (0.57–2.39) |

| Lung (ICD-10:C33-C34) | 228 | 2.4 | 8 | 2.1 | 1.00 | (0.49–2.02) | 0.95 | (0.47–2.40) | 0.95 | (0.35–2.61) |

| Non-cancer, non-circulatory system disease | 1370 | 14.7 | 151 | 43.2 | 2.79 | (2.35–3.30) | 2.67 | (2.25–3.17) | 2.66 | (2.22–3.19) |

Rate*: per 10 000 person-years (age-standardised).

Multivariate-adjusted*: adjusted for age, BMI (<18, 18–20.9, 21–22.9, 23–24.9, 25–26.9, ≥27), alcohol intake (non-drinker, <150, 150–299, 300–450, ≥450 g/week (women, ≥300 g/week)), smoking (never, past, <20, ≥20 cigarettes /day), history of hypertension, leisure-time physical activity. Stratified by area.

BMI, body mass index.

The HR of diabetes on mortality was larger among participants with diabetes diagnosed before baseline than among participants diagnosed after baseline (table 3). Differences of HRs between participants diagnosed between baseline and 5-year survey and participants diagnosed between 5 and 10-year survey were not clear.

Table 3.

Difference of the association between diabetes and mortality by diagnosed period (All-cause mortality)

| Men |

Women |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed period | n | Cases | Adjusted HR* |

n | Cases | Adjusted HR* |

||

| Never | 41 036 | 6975 | 1 | 50 555 | 4106 | 1 | ||

| Before baseline | 2761 | 856 | 1.59 | (1.48–1.71) | 1525 | 345 | 2.00 | (1.79–2.23) |

| Between baseline and 5-year survey | 1341 | 254 | 1.20 | (1.05–1.36) | 861 | 123 | 1.55 | (1.29–1.86) |

| Between 5 and 10-year survey | 879 | 138 | 1.22 | (1.03–1.44) | 626 | 66 | 1.45 | (1.14–1.86) |

Adjusted HR*: adjusted for BMI (<18, 18–20.9, 21–22.9, 23–24.9, 25–26.9, ≥27), alcohol intake (non-drinker, <150, 150–299, 300–450, ≥450 g/week (women, ≥300 g/week)), smoking (never, past, <20, ≥20 cigarettes /day), history of hypertension, leisure-time physical activity. Stratified by area.

BMI, body mass index.

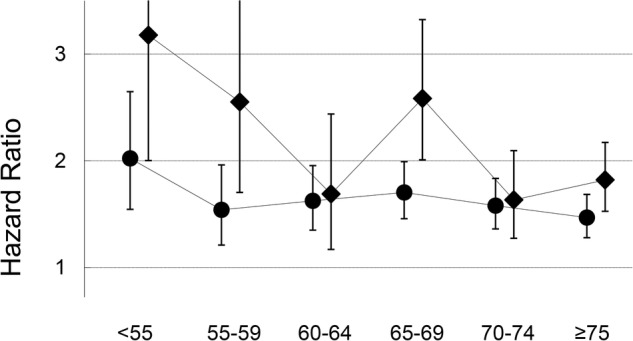

No significant interaction was observed between adjustment factors and the results were essentially unchanged by including the effect of birth cohort. Further adjustment for medication for hypercholesterolaemia had little impact on our results. We found no violation of proportionality assumption. However, although it was not confirmed statistically, there was a tendency that the HR of diabetes for death decreased as age increased (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes of HR of diabetes according to age (all-cause mortality; Men, circle; Women, diamond).

Discussion

In this population-based prospective study of middle-aged Japanese, we observed the increased risk of death for participants with diabetes. As for the cause of death, diabetes was associated with increased risk of death by circulatory system diseases and ‘non-cancer, non-circulatory system disease’, while the association with the risk of death from cancer was moderate.

There are many literatures about diabetes and mortality and substantial numbers of these results were combined into the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration (ERFC).6 In ERFC, the HRs among participants with diabetes compared with participants without diabetes were reported as 1.80 for all-cause mortality, 1.25 for death from cancer, 2.32 for death from vascular causes and 1.73 for death from other causes.

Results of another large prospective cohort study of one million US adults (CPS-II) was also published.7 In the study, relative risk of all-cause mortality was 1.73 for men and 1.90 for women and that of cancer death was 1.07 for men and 1.11 for women and that of cardiovascular system death was 1.92 for men and 2.09 for women.

Recently published meta-analysis also reported increased mortality among participants with diabetes and the relative risk for all-cause mortality was 1.57 for men and 2.00 for women and that of cardiovascular mortality was 1.76.8

Although the results were almost similar, there is a difference of major causes of death between our study and these studies. In the present study, 41% and 25% of all deaths were caused by cancer and circulatory system disease, respectively, while these numbers were 34% and 36% in the ERFC and 15% and 50% in the CPS-II, respectively. This tendency that Japanese die from cancer more than from circulatory system disease and that this is opposite for western people (although ERFC was a collation of over 100 prospective studies, about 90% of the participants were from North America or Europe), is also observed in the world statistics.9 As discussed above, diabetes was associated with increased risk of death by circulatory system disease more than death by cancer. This may seem as if the association between diabetes and mortality is stronger in a population among which the major cause of death was circulatory system disease, that is, the association is stronger among western people than Japanese. However, this is not true because ‘non-cancer, non-circulatory system disease’ plays an unignorable part of mortality.

Our results were also almost consistent with the Japanese large scale cohort study (Takayama study).10 The most remarkable difference between the Takayama study and the present study was the risk of death by coronary heart disease among women. In the Takayama study, the risk of death by coronary heart disease among women were lower in participants with diabetes than participants without diabetes (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.07 to 3.57). As shown in the wide CI, this difference may come from the very low number of cases (only two cases) of coronary heart disease death among women with diabetes. The collaborate study in Asia11 and meta-analysis including this collaborate study12 and its update13 reported the increased risk of coronary heart disease among women with diabetes and our results were consistent with these reports. Our study revealed that the effect of diabetes on the risk of cardiovascular death was greater among women than among men. This is also consistent with the aforementioned meta-analysis.12 13 Although several possible explanations, such as (1) a heavier burden of cardiovascular risk factors, (2) a major impact of some cardiovascular risk factors and/or diabetes per se on cardiovascular disease, (3) differences in the structure and function of heart and vessels and (4) disparities in medical treatment as well as gender differences in treatment response, are postulated, the underlying mechanism of this sex difference in the impact of diabetes on cardiovascular disease is not elucidated well.14

As for the death from cancer, our results were almost consistent with the report about the incidence of cancer in the same JPHC study.15 In the case of incidence, diabetes moderately increased the risk of all cancer and the risk was especially high for cancer of the liver, pancreas and kidney among men and for cancer of the stomach, liver and ovary among women. In the present study, a similar tendency was observed among men, however the number of death from cancer was small among women and the increased mortality risk associated with diabetes was observed only in liver cancer.

We found that the association between diabetes and mortality was stronger among participants diagnosed before baseline than among participants diagnosed after baseline. This result suggests that the effect of diabetes on mortality becomes stronger as duration of diabetes becomes longer.

We also found, although not confirmed statistically, that the HR of diabetes for death decreased as age increased. The similar phenomenon was observed in the ERFC. The reason is unclear. However, one possible explanation is that patients with diabetes who lived long managed their diabetes relatively well. Another possible explanation is that the patients with diabetes with older age included more recently developed diabetes because the risk of diabetes increases as age increases and, as stated above, the association between diabetes and mortality was relatively weaker in newly developed diabetes.

The strength of our study was the large number of participants. The number of participants was about 3.4 times that of the Takayama study. Another strength of the present study was that it was based on the general population in Japan. Although this study was conducted on participants who responded to the baseline questionnaire, we believe that the high-response rate (80.9%) makes it possible to assess the association between diabetes and mortality in the general population. In addition, the age-specific mortality rates in the present study were similar to those of Japanese general population. For example, age-specific mortality rates (per 10 000 person-years) in the present study in men were 15.5, 36.3, 83.0 and 224.0 for 40, 50, 60 and 70-years-old, respectively, and those of Japanese general population (Abridged Life Tables For Japan 2005) were 14.4, 35.8, 89.4 and 213.8. In women, the age-specific mortality rates (per 10 000 person-years) in the present study were 5.3, 17.4, 33.2 and 87.2 for 40, 50, 60 and 70-years-old, respectively and those of Japanese general population were 7.5, 17.7, 36.6 and 89.3. No large discrepancies in mortality rates exist between our study and Japanese general population and this may also support the representativeness of our cohort.

There are several methodological limitations in the present study. The assessment of diabetes mellitus was based on a self-report. Although the sensitivity (82.6%) and specificity (99.7%) of diagnosed diabetes were reported to be high, the proportion of participants with diabetes at baseline (6% for men and 2.8% for women) was low compared with the estimates in the same period (9.9–13.1% for men and 9.1–11.5% for women).16 The assessment of diabetes by self-report, therefore, is most likely an underestimate and our results may have been distorted toward null by this misclassification. However, in the aforementioned meta-analysis, sensitivity analyses were performed and no difference was found in the ratio of the relative risks for diabetes between the method of diabetes diagnosis (self-report vs glucose measured).12 Previous studies have revealed the association between mortality and glycaemia in patients with diabetes 17 and this association holds even in the non-diabetic range of glycaemia.7 18 Since we have no data about glycaemia, we could not assess the association between mortality and glycaemia in the present study.

Despite these limitations, our present study revealed the association between diabetes and mortality in the Japanese general population. Recent increase in patients with diabetes will influence the longevity of Japanese people in the future and we believe that our study would provide useful information both for further research and treatment of diabetes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Mayako Takemoto for her support in preparing the manuscript in English.

Footnotes

Contributors: MK analysed data, drafted the manuscript, reviewed and edited the manuscript and contributed to discussion. MN and ST conducted, designed and supervised the study, and contributed to discussion. TM, AG, YT, YM, AN, HI, MI and NS reviewed the manuscript and contributed to discussion. MN is the guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The present study was supported by National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (23-A-31(toku) and 26-A-2) (since 2011) and a Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (from 1989 to 2010) and a Health Sciences Research Grant (Research on Comprehensive Research on Cardiovascular Diseases H19-016) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Competing interests: MI is the beneficiary of a financial contribution from the AXA Research fund as a chair holder on the AXA Department of Health and Human Security, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo.

Ethics approval: National Cancer Center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics, 2011.

- 2.National Institute of Health and Nutrition. Outline of the National Health and Nutrition Survey Japan 2007.

- 3.Tsugane S, Sobue T. Baseline survey of JPHC study—design and participation rate. Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study on Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases. J Epidemiol 2001;11(6 Suppl):S24–9. 10.2188/jea.11.6sup_24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato M, Noda M, Inoue M et al. . Psychological factors, coffee and risk of diabetes mellitus among middle-aged Japanese: a population-based prospective study in the JPHC study cohort. Endocr J 2009;56:459–68. 10.1507/endocrj.K09E-003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korn EL, Graubard BI, Midthune D. Time-to-event analysis of longitudinal follow-up of a survey: choice of the time-scale. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:72–80. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A et al. . Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med 2011;364:829–41. 10.1056/NEJMoa1008862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saydah S, Tao M, Imperatore G et al. . GHb level and subsequent mortality among adults in the U.S. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1440–6. 10.2337/dc09-0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nwaneri C, Cooper H, Bowen-Jones D. Mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus: magnitude of the evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2013;13:192–207. 10.1177/1474651413495703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Health statistics and health information systems: mortality data. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/mortality/en/index.html.

- 10.Oba S, Nagata C, Nakamura K et al. . Self-reported diabetes mellitus and risk of mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer in Takayama: a population-based prospective cohort study in Japan. J Epidemiol 2008;18:197–203. 10.2188/jea.JE2008004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodward M, Zhang X, Barzi F et al. . The effects of diabetes on the risks of major cardiovascular diseases and death in the Asia-Pacific region. Diabetes Care 2003;26:360–6. 10.2337/diacare.26.2.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huxley R, Barzi F, Woodward M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2006;332:73–8. 10.1136/bmj.38678.389583.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters SE, Huxley R, Woodward M. Diabetes as risk factor for incident coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 64 cohorts including 858,507 individuals and 28,203 coronary events. Diabetologia 2014;57:1542–51. 10.1007/s00125-014-3260-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivellese AA, Riccardi G, Vaccaro O. Cardiovascular risk in women with diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2010;20:474–80. 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Otani T et al. . Diabetes mellitus and the risk of cancer: results from a large-scale population-based cohort study in Japan. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1871–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuzuya T. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in Japan compiled from literature. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1994;24(Suppl):S15–21. 10.1016/0168-8227(94)90222-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA et al. . Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321: 405–12. 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khaw KT, Wareham N, Luben R et al. . Glycated haemoglobin, diabetes, and mortality in men in Norfolk cohort of European Prospective Investigation of Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Norfolk). BMJ 2001;322:15–18. 10.1136/bmj.322.7277.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]