Abstract

Robust sex differences in brain and behaviour exist in zebra finches. Only males sing, and forebrain song control regions are more developed in males. The factors driving these differences are not clear, although numerous experiments have shown that oestradiol (E2) administered to female hatchlings partially masculinises brain and behaviour. Recent studies suggest that an increased expression of Z-chromosome genes in males (ZZ; females: ZW) might also play a role. The Z-gene tubulin-specific chaperone A (TBCA) exhibits increased expression in the lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) of juvenile males compared to females; TBCA+ cells project to the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA). In the present study, we investigated the role of TBCA and tested hypotheses with respect to the interactive or additive effects of E2 and TBCA. We first examined whether E2 in hatchling zebra finches modulates TBCA expression in the LMAN. It affected neither the mRNA, nor protein in either sex. We then unilaterally delivered TBCA small interfering (si)RNA to the LMAN of developing females treated with E2 or vehicle and males treated with the aromatase inhibitor, fadrozole, or its control. In both sexes, decreasing TBCA in LMAN reduced RA cell number, cell size and volume. It also decreased LMAN volume in females. Fadrozole in males increased LMAN volume and RA cell size. TBCA siRNA delivered to the LMAN also decreased the projection from this brain region to the RA, as indicated by anterograde tract tracing. The results suggest that TBCA is involved in masculinising the song system. However, because no interactions between the siRNA and hormone manipulations were detected, TBCA does not appear to modulate effects of E2 in the zebra finch song circuit.

Keywords: sex difference, song system, neural development, sex chromosome

Sex differences in brain and behaviour exist across vertebrates. Developmental oestradiol (E2) commonly masculinises neural structure and function (1). However, the responsible molecular mechanisms are largely unknown (2). Zebra finches represent particularly useful models for investigating these factors. Only males sing, and the brain regions regulating song learning and production are sexually dimorphic. Within the song circuit, the HVC (3) projects to the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA); both are cortical structures that contain more and larger cells in males (4). The lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) also projects to the RA (5). Sexual differentiation of the HVC and RA occurs at a relatively high rate around post-hatching day 25 (D25) and involves cell death in the female RA (6,7). The LMAN remains similar in size between the sexes, although its projection to the RA declines in juvenile females between D25 and adulthood (8). Lesions to the LMAN in juvenile birds cause cell loss in the RA (9,10), which can be rescued with neurotrophins (11), suggesting that input from the LMAN to the RA may normally be critical for RA cell survival.

As in mammalian systems, E2 has masculinising effects in female zebra finches. For example, treatment of hatchlings partially increases the volume of the HVC and RA, as well as cell size and number within them (4). E2 added to female cultures also facilitates the growth of male-specific HVC projections into the RA (12). However, with the exception of this projection, limiting E2 availability (13,14) or action (15,16) in males does not prevent masculine development. Thus, additional factors are likely important (17).

Male birds are homogametic (ZZ; females: ZW) and dosage compensation is limited (18), so Z-genes might contribute to masculinisation of the brain. Microarray and subsequent studies identified several Z-genes that may be involved (19–23). One is tubulin specific chaperone A (TBCA), a protein critical for β-tubulin formation (24,25). A specific sex difference in TBCA expression within the song system exists. In development, but not adulthood, TBCA is increased in males compared to females only in the LMAN. A majority of these TBCA+ cells are neurones, many of which project to the RA (26,27). Thus, TBCA is positioned to influence sexually dimorphic development of RA.

The present studies represent an initial step in evaluating the idea that both E2 and Z-gene(s) are required for full masculinisation of the song circuit. In addition to testing the direct effects of inhibiting TBCA in the LMAN of juvenile birds, we evaluated two ways in which TBCA might interact with E2 to facilitate masculinisation. We investigated whether E2 increases TBCA availability in the LMAN and also tested whether TBCA in the LMAN modulates the ability of E2 to masculinise the song circuit.

Materials and methods

Animals and tissue collection

Zebra finches were reared in walk-in aviaries, each of which contained five to seven male and female pairs with their offspring. Nest boxes were checked every day, and new hatchlings were toe-clipped for unique identification. Portions of the removed toes were used to determine the genetic sex of each individual by polymerase chain reaction (28). Animals were kept under a 12 : 12 h light/dark cycle, and provided seed (Kaytee Finch Feed; Chilton, WI, USA), water, gravel and cuttlebone ad lib. Each week, their diets were supplemented with spinach, oranges, hard-boiled chicken eggs and bread.

For all studies, birds were killed by rapid decapitation, and their brains were removed and immediately frozen in cold methyl-butane. Tissue was stored at −80 °C with desiccant until processing. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institute of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Michigan State University.

Experiment 1: Effects of increasing E2 on TBCA expression in the LMAN

Hormone manipulation

On D3, each male and female bird received a s.c. implant of either E2 or a blank control, in accordance with Tang and Wade (29). Implants were synthesised using a 1 : 5 uniform mixture of 17β-oestradiol (Steraloids, Welton, NH, USA) and silicone sealant (Type A; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA), which was extruded through a 3-ml syringe in a straight line onto waxed paper and dried overnight. The mixture was cut into 1-mm lengths, which were then further divided to provide 100 μg of E2 per pellet. Blank capsules were produced the same way without the addition of the hormone. Brains were collected at D25, as noted above, and processed for either immunohistochemistry (IHC) or in situ hybridisation to detect protein and mRNA, respectively. At this time, all birds were checked to confirm the continued presence of the pellet and that those with oestradiol still contained some crystalline hormone.

Immunohistochemistry

Brains (n = 7 per sex per treatment) were coronally sectioned at 20 μm, and thaw-mounted in six series onto SuperFrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The TBCA primary antibody was validated in accordance with Qi and Wade (27), where the IHC protocol is described in detail. Briefly, one series of slides was warmed to room temperature, rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Tissue was then treated with 0.9% hydrogen peroxide in methanol, incubated in 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100, and finally incubated in TBCA primary antibody (2 μg/ml #SAB1100935; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) in 0.1 M PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% NGS for 24 h at 4 °C. The next day, after rinses in PBS, the tissue was incubated in a biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1 μg/2 ml #BA-1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 2 h at room temperature. The protein was visualised with Elite ABC reagents (Vector Laboratories) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, including diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich) with 0.0024% hydrogen peroxide. After the colour reaction, slides were rinsed in PBS, dehydrated in a series of ethanols and coverslipped with DPX (Sigma-Aldrich).

TBCA protein labelling in the LMAN was quantified using STEREO INVESTIGATOR software (Microbrightfield, Inc., Williston, VT, USA) without knowledge of the animal’s sex or treatment. The optical fractionator function was used to estimate the total number of TBCA positive cells in and the volume of the LMAN. Labelled cells were defined as those with a distinct neuronal morphology exhibiting a brown cytoplasmic reaction product. The borders of the LMAN on one side of the brain (randomly selected) were defined by tracing its edge, and the number of cells within it was determined manually in sampling sites determined by the software. The density of TBCA labelled cells was calculated by dividing the estimate of the total number by the volume of the LMAN. Parameters for acceptable coefficient of errors were based on Slomianka and West (30).

A two-way ANOVA was used (SPSS, version 21.0; IBM Armonk, NY, USA) to analyse the effects of sex and treatment on the estimated total cell number, volume defined by TBCA labelling and density of labelled cells in the LMAN.

In situ hybridisation

Adjacent tissue sections from the same animals used in the IHC study were used for in situ hybridisation. One E2 treated female and one control male were not included because their tissues were used for another study (final sample sizes for males: E2 = 7, blank = 6; females: E2 = 6, blank = 7). Two adjacent sets of tissue sections from each animal were used: one for antisense and one for control, sense probes. The probes and protocol were the same as described in Qi et al. (26). Briefly, the tissue was rinsed in PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and dehydrated in a series of ethanols. The slides were then incubated in pre-hybridisation buffer for approximately 2 h before they were exposed to 33P-UTP-labelled RNA probes overnight (20–24 h). The tissue was washed in saline-sodium citrate buffers to remove excess probe and then dehydrated in a series of ethanols. Representative slides from each group were exposed to a phosphor-imaging screen (Kodak #170-7841; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 16 h and scanned with a Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad) to confirm the signal in the LMAN. Slides were then dipped in NTB emulsion (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) and stored in the dark at 4 °C for 5 weeks. They were then developed using Kodak D-19 developer and fixer (Eastman Kodak) and lightly counter-stained with cresyl violet to facilitate identification of the brain anatomy.

The analysis was also completed in the same manner as that described in Qi et al. (26), without knowledge of each animal’s sex or treatment group. The LMAN was first identified using bright field microscopy, and then captured in dark field using IMAGEJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The threshold function was used to manually define the silver grains covering a box (0.052 mm2) placed over the centre of the LMAN. The software calculated the percentage of this area covered by this labelling. This procedure was used in each section containing LMAN on both the left and right sides of the brain. Background labelling from adjacent sections that were exposed to the sense probe was subtracted from values obtained from anti-sense treated sections. The resulting values were averaged within individuals.

A two-way ANOVA was used to analyse the effects of sex and treatment on the percent area covered by silver grains in the LMAN.

Nissl staining

A final series of sections (n = 7 per sex per treatment) was stained with thionin to validate that the E2 treatment had an effect on the brain. Area X is not normally visible in females, although it becomes distinct after posthatching E2 treatment (31). Females were inspected for the presence or absence of Area X by an observer who was blind to hormone treatment. In addition, because we are unaware of any report of the effects of early E2 on juvenile LMAN volume [but, for adult brains, see Grisham et al. (32)], the volume of this region was quantified in all individuals. Cross-sectional areas were determined by tracing the border of LMAN on each side of the brain using IMAGEJ in each section that it was visible. Unilateral volumes of the brain region were estimated by multiplying the sum of these areas by the sampling interval (0.12 mm). Values for the left and right sides of the brain were averaged. A two-way ANOVA was used to analyse the effects of sex and treatment on LMAN volume.

Experiment 2: Effects of TBCA inhibition and E2 modulation on song system morphology

Validation of TBCA small interfering (si)RNA manipulation

siRNAs were generated by Ambion (Custom Ambion in vivo siRNA; Ambion Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) based on the TBCA mRNA sequence from GenBank (Accession number DQ214986). Three sequences, each of 21 nucleotides, were designed for maximum efficacy and of a size (< 30 nucleotides) that should not initiate nonspecific protein synthesis or RNA degradation. These sequences were combined for transfection into a pseudoviral envelope. This haemagglutinating virus of Japan envelope (HVJ-E; Genome-ONE-Neo EX HVJ-E; Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd, Koto-ku, Tokyo, Japan) is a replication-incompetent vector developed from the Sendai virus (33). The viral genome is inactive, and only the cell membrane fusion properties are intact, allowing effective delivery of siRNAs into cells without eliciting a cytotoxic response (34).

A pilot study (n = 3 males/group) assessed degree of protein knockdown using several siRNA doses (10, 20, 30 pM) across survival times (4, 7, 10 days). The three sequences were first diluted in nuclease free water to achieve the three concentrations, and stored at −20 °C until use. Before surgery, each siRNA dose was transfected into a pellet containing the HVJ-E vector, in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions for the treatment of laboratory animals. A control sequence (Control siRNA-J: sc-44238; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) was prepared in the same way and transfected at the same time. Similar to the other siRNAs, this sequence of comparable length activates the RISC complex but does so without degradation of a target as a result of a lack of complementarity to any known cellular mRNA. Based on the results of this study, a more comprehensive analysis was conducted using the 30 pM dose and the 10-day survival time that included both males (n = 6) and females (n = 7).

For all intracranial injections, birds were anaesthetised with isoflurane, and positioned in a stereotaxic instrument (model 900; KOPF Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). Injections into the LMAN were unilateral, so that one hemisphere received TBCA siRNA, whereas the contralateral side received the control sequence. Injections were 4.8 mm anterior to the bifurcation of the midsaggital sinus (lambda), 2.0 mm lateral to the midline and 1.5 mm ventral from the surface of the skull. siRNA and the control (1 μl each) were infused over 5 min, at a rate of 0.2 μl/min. All animals were returned to their home aviaries until they were killed.

Animals were killed by rapid decapitation, and their brains were immediately frozen in cold methyl-butane and stored at −80 °C until sectioning. Brains were coronally sectioned at 300 μm and thaw-mounted onto Super-Frost Plus slides. As described in Qi and Wade (27), LMAN was removed using a 17-gauge micropunch (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). For each animal, three punches were obtained from the centre of the LMAN in each hemisphere, and were pooled within an animal. Punches from the two sides of the brain were kept separate to distinguish between the siRNA and control treatments. Tissue punches were immediately suspended in cold RIPA lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and homogenised using a sonic dismembrator (Fisher Scientific). Samples were then centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The protein supernatants were collected, and a small volume of each sample was used for concentration quantification using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The remainder of each sample was stored at −20°C until western blot analysis.

Protein (30 μg) per sample was loaded into 4–20% mini-protean TGX gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories) along with a Kaleidoscope pre-stained standard (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Samples were divided among seven gels, although the proteins from the two sides of the brain for each individual were always on the same gel. Male and female samples were run on separate gels because of differences in optimal film exposure times. Separated samples were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) at 4°C. Membranes were then cut in half so that TBCA (13 kDa) and the loading control, actin (43 kDa), could simultaneously be probed.

Each membrane was incubated in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h at room temperature to prevent nonspecific binding. TBCA (2 μg/ml) and actin primary antibodies (1 μg/ml; #SC-1615; Santa-Cruz Biotechnology) were applied to their respective membranes at 4°C overnight. The blots were exposed to horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies for TBCA (dilution 1 : 5000; #7074; Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) and for actin (1 μg/15 ml; #SC-2020; Santa-Cruz Biotechnology). After washes in PBS, the membranes were processed for enzyme-linked chemiluminescent detection (ECL Plus; GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) followed by exposure to autoradiography film (HyBlot CL; Denville Scientific Inc., Metuchen, NJ, USA). The film was developed using Kodak Professional D-19 developer and fixer.

A ratio of the optical densities of TBCA and actin, corrected for neighbouring background, was calculated for each animal using IMAGEJ. Paired t-tests were used to evaluate differences between siRNA and control samples within males and females.

Hormone manipulations in experimental animals

Females were administered either an E2 or blank implant on D3 as in Experiment 1. Also starting on D3, and continuing until they were killed, male birds received daily injections of 20 μg of fadrozole hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) in 10 μl of 0.75% saline into the breast muscle. This manipulation is highly effective in reducing brain aromatase in developing zebra finches (35). Control males received the same volume of 0.75% saline. Each bird then received a manipulation of TBCA in the LMAN. Two studies were conducted: one to assess morphology within the LMAN and RA, and the other to quantify the projection between these regions.

Morphology of the LMAN and RA

Between D15 and D17, males and females received stereotaxic injections of TBCA siRNA and control siRNA into the LMAN, as described above. One bird was eliminated from analysis because of damaged tissue in the LMAN, and two were not used because the injection sites were lateral to the LMAN. Final sample sizes are indicated below. Birds were returned to their home aviaries after surgery and killed 10 days later. Their brains were removed and immediately frozen in cold methyl-butane and stored at −80°C. They were coronally sectioned at 20 μm, and thaw-mounted in six series onto SuperFrost Plus slides.

One series of slides from each animal (final sample sizes for males: fadrozole = 10, saline = 9; females: E2 = 7, blank = 9) was processed for TBCA immunoreactivity to confirm the efficacy of the siRNA treatment in the LMAN. The protocol for TBCA IHC was identical to that used in Experiment 1. Photographs of LMAN were captured using IMAGEJ and each image was coded so that hormone treatment, side of brain and sex were blind to the observer. To obtain an estimate of relative numbers of TBCA+ cells in the LMAN, the cell counter plug-in in IMAGEJ was used to mark individual cells within this region. As in Experiment 1, TBCA+ cells were defined as those with a distinct neuronal morphology exhibiting a brown cytoplasmic reaction product for the DAB. An estimate of relative TBCA+ cell numbers for each side of LMAN was obtained by taking the average of the cell counts through each section in which LMAN was identifiable. The possibility that a cell was counted twice is extremely low because alternate tissue sections were 0.12 mm apart. The average across sections was used because for a few individuals, cells could not be reliably counted in one section because of extremely light labelling.

A second series of slides from each animal (final sample sizes for males: fadrozole = 11, saline = 9; females: E2 = 7, blank = 9) was stained with thionin for confirmation of accurate injections into LMAN and for analysis of morphology in both the LMAN and its target (i.e. RA). Photographs of each section containing the LMAN and RA were captured using IMAGEJ, and the files were coded so that hormone treatment, side of brain and sex were blind to the observer. Cross-sectional areas and volumes of the LMAN and RA were determined as in Experiment 1. Cell counts were obtained in the RA of thionin-stained sections in the same manner as TBCA labelled cells were quantified in the LMAN. However, because these cells were readily quantifiable in every tissue section, a total of the counts was analysed rather than an average per section.

To obtain an estimate of soma size in the RA, the borders of 20 randomly selected cells were traced within each of the three most anterior sections of RA using IMAGEJ. Values from the two sides of the brain were kept separate so that comparisons could be made within each animal. Averages were calculated from the 60 cells per hemisphere.

Mixed model ANOVAs (siRNA within animals, hormone manipulation between individuals) were used to analyse each variable: number of TBCA+cells, volumes of LMAN and RA, as well as RA cell size and number, based on Nissl staining. These analyses were conducted separately for males and females because they received different methods of hormone administration (injections versus implants).

LMAN to RA projection

Between D15 and D17, males and females received stereotaxic injections of TBCA siRNA and its control into LMAN, as described above. In this set of birds, however, immediately after siRNA injections, cannulae were replaced within their guides and 1 μl of 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI; Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; 0.1% in dimethylsulphoxide) was infused over 5 min at a rate of 0.2 μl/min into both sides of the LMAN. Birds were returned to their home aviaries after surgery and killed 10 days later. The brains were removed, immediately frozen in cold methyl-butane, and stored at −80°C. They were coronally sectioned at 20 μm, and thaw-mounted in six series onto SuperFrost Plus slides.

One series of slides from each animal was stained with thionin to confirm that the injection site was limited to the LMAN. Microscopic inspection of the tissue showed that a few animals received DiI ventral to the LMAN, and some exhibited unequal amounts of DiI in the two hemispheres. These were not included in the analysis (final sample sizes were males: fadrozole = 7, saline = 6; females: E2 = 11, blank = 9). A second series of slides was processed for quantification of DiI in the RA. Slides were warmed to room temperature, rinsed in 0.1 M PBS, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. They were then rinsed in PBS, dipped in water and cover-slipped with ProLong Gold mounting medium (Ambion Life Technologies). Slides cured at room temperature for 48 h, and were then stored in the dark at 4°C until analysis.

Photographs of RA were captured using IMAGEJ under a TRITC filter, and the images were coded so that treatment and sex were blind to the observer for analysis. Adjacent tissue sections from the Nissl-stained slides were used to confirm the anatomical resolution of the RA. The border was traced in the fluorescent images in every section in which the brain region was visible. The threshold function (default settings) was then used to manually highlight the DiI labelling within each RA trace. IMAGEJ calculated the percentage of the cross-sectional area for the RA that was covered by DiI. Values within each side of RA in each animal were averaged, and a mixed model ANOVA was used to analyse the effects of siRNA treatment (within animals) and hormone manipulation (between animals). Males and females were also kept separate for these analyses.

Results

Experiment 1: E2 does not increase TBCA mRNA or protein

In situ hybridisation

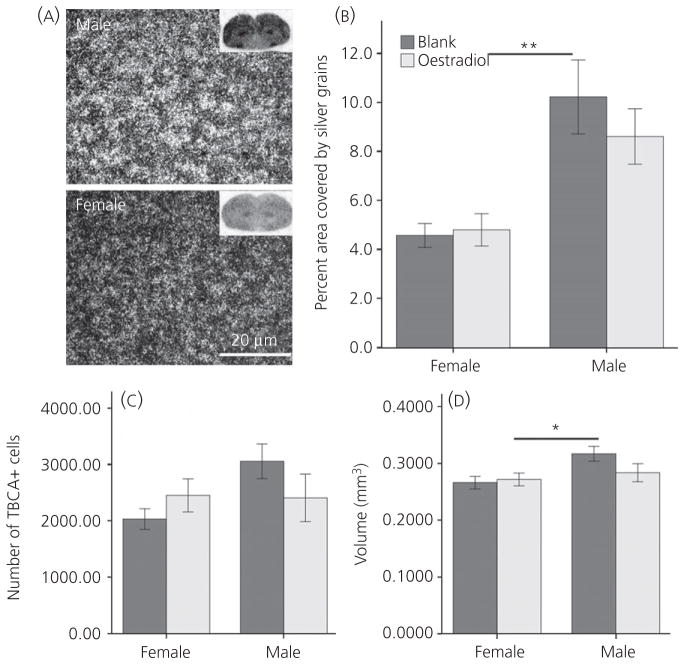

As expected, increased TBCA mRNA was detected in the LMAN of males compared to females, as indicated by a main effect of sex in silver grain density (F1,22 = 21.92, P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A,B). However, no effect of treatment (F1,22 = 0.470, P = 0.500) or interaction between sex and treatment (F1,22 = 0.832, P = 0.372) was observed.

Fig. 1.

In situ hybridisation and immunohistochemistry for tubulin-specific chaperone A (TBCA) in the lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) after oestradiol manipulation. (A) Darkfield images of silver grains from the centre of the LMAN with inserts from a phosphor-imager screen of full coronal sections. (B) Relative densities of silver grain labelling. (C) Stereologically estimated number of TBCA+ cells. (D) Volume of the LMAN defined by TBCA immunoreactivity. All values represent the mean ± SE; main effects of sex: *P = 0.024, **P < 0.001.

Immunohistochemistry

Effects of sex and treatment were not detected on the estimated number of cells expressing TBCA protein, and the variables did not interact (all F1,24 < 2.91, P > 0.100) (Fig. 1C). However, the volume defined by this labelling was greater in males than in females (F1,24 = 5.844, P = 0.024) (Fig. 1D). Neither an effect of E2, nor an interaction between E2 and sex was detected on this measure (both F1,24 < 2.26, P > 0.145). There were no main effects of sex or hormone treatment on the density of labelled cells, and the variables did not interact (all F1,24 < 1.66, P > 0.200; not shown).

Nissl staining

No effects of sex or E2 were detected on the volume of LMAN (all F1,24 < 2.47, P > 0.128; not shown).

Experiment 2: TBCA siRNA in the LMAN effectively inhibits local protein expression, and demasculinises the LMAN and RA, as well as the projection between them

siRNA effectiveness

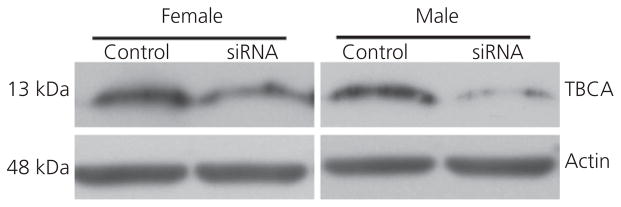

Western blot analyses used to validate the treatment paradigm indicated that TBCA-specific siRNA significantly decreased relative levels of this protein, compared to the control treatment, in both females (t6 = 4.144, P = 0.006) and males (t5 = 2.631, P = 0.046) (Fig. 2). In females, protein was decreased by 59% on average and, in males, it was decreased by 71%. Analysis of the loading control, actin, alone indicated no effect of the siRNA manipulation in either females (t6 = 0.493, P = 0.640) or males (t5 = 1.256, P = 0.265), suggesting specificity of the manipulation.

Fig. 2.

Western blots using protein extracted from micropunches of the lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) from two zebra finches. In each bird, the LMAN on one side of the brain received a control sequence and the other received the tubulin-specific chaperone A (TBCA) small interfering (si)RNA.

In alternate sections used for the quantification of morphology (see below), we used IHC to confirm effectiveness of the siRNA manipulation in experimental animals. This treatment significantly reduced the average number of detectable TBCA+ cells per section of LMAN in both females (F1,14 = 8.234, P = 0.012) and males (F1,17 = 15.81, P = 0.001; not shown).

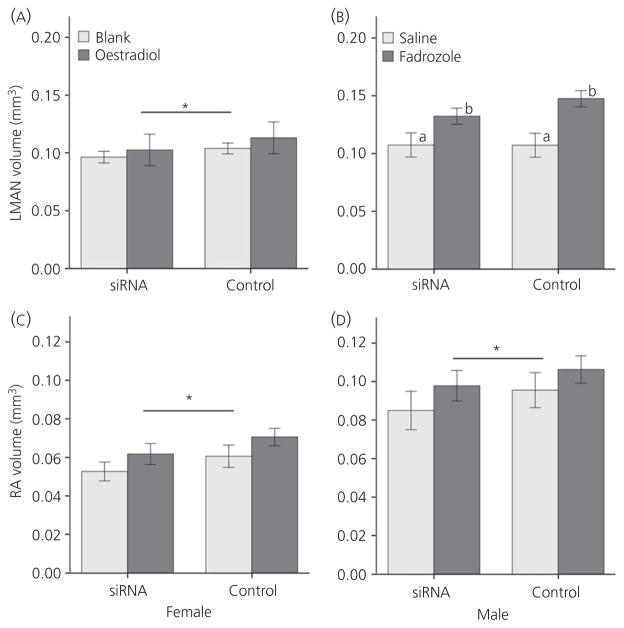

Effects of siRNA and hormone manipulation on LMAN volume

In females, TBCA siRNA significantly decreased LMAN volume in thionin-stained tissue (F1,14 = 5.325, P = 0.037) (Fig. 3A), although there was no main effect of hormone treatment (F1,14 = 0.377, P = 0.549) or interaction between the variables (F1,14 = 0.142, P = 0.712). In males, the TBCA siRNA manipulation did not reduce LMAN volume (F1,18 = 2.261, P = 0.150) (Fig. 3B) and no interaction between siRNA and hormone treatments was detected (F1,18 = 2.375, P = 0.141). There was, however, a main effect of hormone treatment, such that the volume of LMAN was greater in males treated with fadrozole than saline (F1,18 = 8.672, P = 0.009).

Fig. 3.

Brain region volumes after tubulin-specific chaperone A (TBCA) small interfering (si)RNA and hormone manipulations. (A) Lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) values in females and (B) data from this area in males. Robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA) volumes are also depicted for (C) females and (D) males. All values represent the mean ± SE; *significant main effect of siRNA, and the different lowercase letters in (B) represent a main effect of fadrozole.

Effects of siRNA and hormone manipulation on the RA

Parallel to its influence on the LMAN, TBCA siRNA reduced RA volume in females as quantified in Nissl-stained tissue (F1,14 = 23.14, P < 0.001) without a main effect of hormone treatment or an interaction between the variables (both F1,14 < 1.72, P > 0.211) (Fig. 3C). Here, the effect was the same in males, with TBCA siRNA reducing RA volume (F1,18 = 13.01, P = 0.002). No main effect of fadrozole or interaction between the siRNA and fadrozole manipulations existed (both F1,18 < 1.02 P > 0.326) (Fig. 3D).

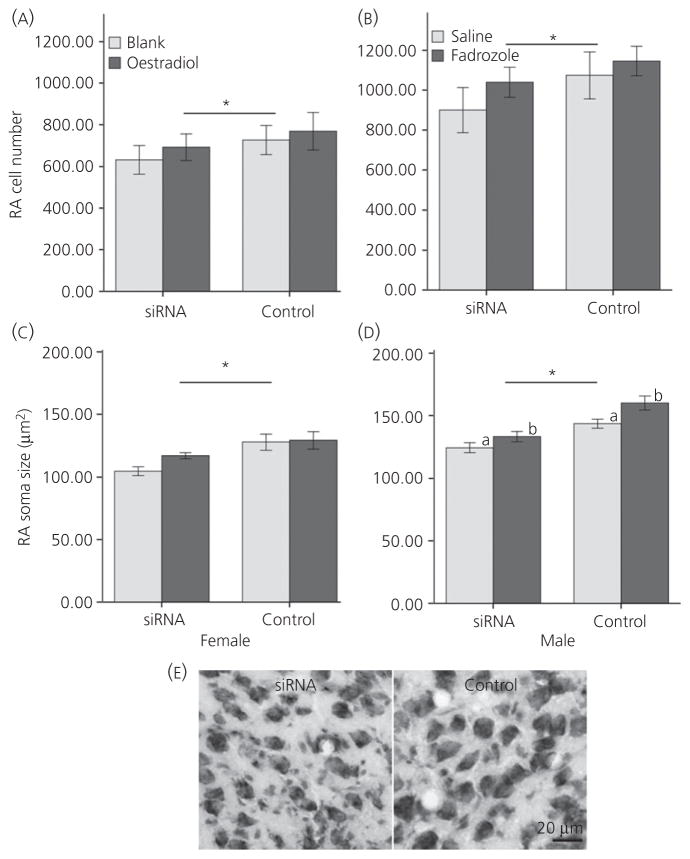

The estimate of relative cell number in the RA was also decreased in females by the TBCA siRNA manipulation (F1,14 = 10.78, P = 0.005), without a main effect of hormone treatment or an interaction between E2 and the siRNA (both F1,14 < 0.26, P > 0.619) (Fig. 4A). The pattern was the same in males, with a main effect of siRNA treatment reducing RA cell number (F1,18 = 21.22, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B) and no effect of hormone manipulation or interaction between the two variables (both F1,18 < 1.23, P > 0.282).

Fig. 4.

Estimated relative numbers of cells in the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA) are depicted in (A) females and (B) males. These values represent the sum of cells counted in every sixth section through the rostrocaudal extent of the brain region. Soma size in this region is indicated for (C) females and (D) males. (E) Representative images of Nissl-stained sections through the centre of RA in a saline-treated male that received tubulin-specific chaperone A small interfering (si)RNA (left) and its control on the opposite side of the brain (right). All values represent the mean ± SE; *significant main effect of siRNA, and the different lowercase letters in (D) represent a main effect of fadrozole.

Finally, RA soma size was also reduced in females as a result of the siRNA compared to control treatment (F1,14 = 16.97, P = 0.001), with no effect of hormone treatment or interaction between the variables (both F1,14 < 1.67, P > 0.217) (Fig. 4C). A parallel main effect of the siRNA existed in males (F1,18 = 47.33, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4D,E). Fadrozole also increased this measure (F1,18 = 5.290, P = 0.034), although no interaction between siRNA and hormone treatment was detected (F1,18 = 1.366, P = 0.258).

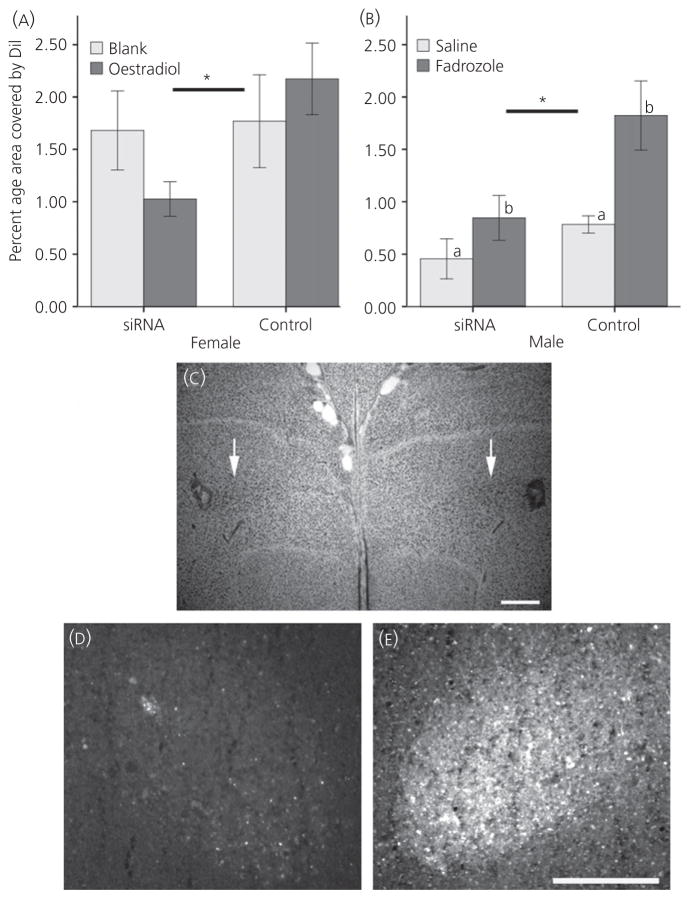

Effects of siRNA and hormone manipulation on the projection from the LMAN to the RA

The percentage of area covered by DiI in the RA after administration to LMAN was diminished by TBCA siRNA treatment in both females (F1,18 = 5.378, P = 0.032) (Fig. 5A,C–E) and males (F1,11 = 7.105, P = 0.022) (Fig. 5B). In females, there was no main effect of E2 treatment (F1,18 = 0.102, P = 0.753) or interaction between siRNA and hormone (F1,18 = 3.953, P = 0.062). However, in males, fadrozole significantly increased the percentage area of RA covered by DiI (F1,11 = 10.26, P = 0.008). No interaction existed between siRNA and fadrozole treatment (F1,11 = 1.760, P = 0.211).

Fig. 5.

Percentage of the area of the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA) filled by DiI after injection in the lateral magnocellular nucleus of the anterior nidopallium (LMAN) in (A) females and in (B) males. All values values represent the mean ± SE; *main effect of small interfering (si)RNA treatment in both sexes, and different lowercase letters in (B) represent an effect of fadrozole in males. (C) Low magnification photo of a Nissl-stained coronal section in an oestradiol-treated female, where the white arrows point to dorsal borders of the LMAN; injection sites are visible in each hemisphere of the LMAN near the edges of the image. Fluorescent images of RA from the same animal are depicted for the (D) siRNA treated side of the brain and (E) control. To be conservative, the quantification of labelling included only the individual, bright puncta that likely represented projections to specific cells, and did not include the general background fill that was common on the control side of RA. Scale bars: (C) 500 μm; (E) 200 μm for both (D) and (E). Dil, 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first set of studies to document specific effects of a sex chromosome gene on avian brain development. Inhibition of TBCA in the LMAN demasculinised soma size and cell number in the RA, as well as RA volume. It also diminished the projection from the LMAN to the RA. Parallel effects occurred in females, with an additional reduction in LMAN volume. However, the role of E2 remains unclear. Although we had considered additive or interactive effects of this hormone and TBCA on masculinisation, the results suggest that neither occurs.

TBCA is involved in song system masculinisation

TBCA is conserved across vertebrates and is one of several chaperones required for the generation of α/β tubulin (36). Human mutations in a β-tubulin gene, TUBB2B, are associated with defective TBCA and result in reduced tubulin heterodimers and abnormal brain development (37). TBCA silencing in mammalian cell lines causes a reduction in soluble tubulin and, eventually, the death of these cells (38). Thus, TBCA in mammalian systems is important for cell survival and normal brain maturation.

The present data on TBCA inhibition are consistent with similar roles in zebra finches. Effects were detected in both sexes despite lower endogenous TBCA levels in females (26,27), suggesting that this Z-gene acts in a similar manner regardless of the genetic sex of the brain and its relative availability likely influences sex differences in song system morphology. The results parallel those from electrolytic lesions of LMAN (9) and ibotenic acid lesions of MAN (10) in juvenile males, which reduce the volume of and cell number in RA. LMAN cells can transport neurotrophins, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), to RA, and infusion of these proteins into RA rescues cell death after deafferentation (11). Thus, the projection from LMAN to RA likely facilitates RA cell survival by providing trophic support. Future work should assess the direct effects of TBCA inhibition in LMAN on BDNF transport to the RA.

The present results differed a bit from Akutagawa and Konishi (10) in that a reduction in RA cell size was not seen after their MAN lesions. It is difficult to speculate on why our relatively specific manipulation in the LMAN produced an effect not seen with the more global destruction of a brain region. However, the difference on this measure may be related to timing, as that previous study manipulated the brain region several days later than we did (D20) and collected the tissue far later (in adulthood). The RAs analysed in our experiment would not yet have received input from the HVC, although they would have in the earlier work; the projection develops in males at approximately 1 month of age.

E2 does not affect TBCA expression in the LMAN

E2 treatment did not modulate TBCA mRNA or protein in the LMAN of juvenile birds of either sex. We had hypothesised that one mechanism by which E2 might facilitate masculinisation, at least when administered to females, is via up-regulation of this protein that is important for neural development. However, the data from Experiment 1 indicate that an increase in circulating levels of this steroid has no effect on TBCA expression in the LMAN of either sex.

Consistent with previous results from juvenile zebra finches (27), TBCA mRNA was greater in the LMAN of males in the present study, although the number of TBCA immunoreactive cells in this brain region did not differ between the sexes. The volume defined by this labelling but not Nissl staining was greater in males. Similarly, a previous assessment of changes in the volume of LMAN in Nissl-stained tissue produced no main effect of sex and parallel developmental trajectories in males and females (39). In our earlier experiment (27), western blot analysis showed a greater concentration of protein in the LMAN of males compared to females at D25. Collectively, these results suggest that the quantity of TBCA per cell may be greater in males. Such a result might make individual cells appear larger in immunostained tissue, which could affect the detection of the borders of the LMAN.

Manipulation of E2 availability produced some novel results

Previous work has documented effects of post-hatching E2 in females on masculinising RA morphology (4) that were not seen in Experiment 2. All females treated with E2 in the present study had an Area X, which is normally not visible without early exposure to E2, whereas none of those receiving blank capsules did. Thus, the steroid functioned in the brains of these birds. Although sites of E2 action on song system structure are not clear, during the period of treatment described in the present study, oestrogen receptor (ER) α mRNA has been detected in the HVC and RA but not in the LMAN or Area X (40). Cells in the HVC and RA are also immunoreactive for the G-protein-coupled membrane bound ER, GPR30, across several juvenile ages (41).

One possibility for the lack of effects in the RA is that mechanical injury caused by inserting cannulae into the LMAN up-regulated aromatase (42). Recent studies in mice suggest that such an increase in oestrogen synthesis can even propagate to beyond the site of injury (Saldanha CJ, Mehos CJ, Blackshear K, and Duncan KA, unpublished observations). Thus, it is possible that E2 levels were increased in both the LMAN and RA in all of the subjects, which minimised any effects that might have been a result of exogenous hormone manipulation.

In males, aromatase inhibition increased RA cell size and LMAN volume, as well as the transport of DiI from the LMAN to the RA. This information on LMAN volume and the projection to the RA is new; these variables had not been evaluated previously after experimental blockade of post-hatching oestradiol synthesis. Data on RA volume in the present study are consistent with earlier work (13); neither study found an effect of fadrozole treatment of juvenile males. However, unlike the present study, the earlier experiment also found no effect on RA cell size. The reason for the difference across the studies is not obvious. The doses were identical, although the earlier experiment treated males from D1 to D30, whereas the present birds were injected from D3 to D25–27. The ages of injected birds are different, although it is unlikely that a shorter duration would have a more potent outcome.

Hypermasculinising effects after manipulation of oestrogenic systems have been detected in zebra finches. Administering the oestrogen receptor blockers tamoxifen, LY117018 or CI628 to males increases a variety of aspects of song system morphology (15,16). Although the mechanisms are unclear, it appears that increased oestrogen availability or action in males has some opposing effects in males and females. These ideas warrant further investigation.

Fadrozole might also have affected brain morphology in the present study by increasing androgen availability. Androgen receptor mRNA is found in both the RA and LMAN of zebra finches (43). Inhibiting aromatase activity increases available testosterone because less of this substrate is metabolised (44,45). Similar to the data from studies on E2, the results from manipulations of androgen or its ability to act are somewhat paradoxical. Treatment of juvenile female zebra finches with 5α-dihydrotestosterone, a non-aromatisable metabolite of testosterone, can increase RA soma size and cell number (46,47). However, data obtained after administration of the anti-androgen flutamide are inconsistent. In one study, treatment of developing males with this drug had no effect on numerous measures of song system morphology, including RA soma size (48). In another, it hypermasculinised volume and neurone number in the RA (47). In a third, castration of juvenile males combined with treatment with the anti-androgen, flutamide, decreased LMAN volume (49). Some, but not all of these data, are consistent with the hypermasculinising effects that we detected in the LMAN and RA after fadrozole treatment; more work is needed to isolate specific mechanisms.

Details regarding the increase in the projection from the LMAN to the RA as a result of fadrozole treatment also need to be further evaluated. However, we can conclude that the mechanisms are different than those involved in masculinising the projection from the HVC to the RA. This male-specific innervation (50,51) is critical for normal RA development in older birds (10) and it does appear to require E2 produced in the brain (12).

Future directions

The history of research into the mechanisms underlying sexual differentiation of the zebra finch song system suggests that both Z-genes and E2 may be important for masculinisation. The present studies demonstrate that inhibition of a specific Z-gene, TBCA, influences song system development. Although siRNA manipulation did not fully demasculinise morphology, several reliable effects were detected in both the LMAN and its target (i.e. RA), suggesting a role for TBCA in maturation of the neural song system.

At least two factors likely account for the magnitude of the effects we detected. The first reflects technology: TBCA protein was not completely eliminated. The second involves biological mechanisms in that numerous additional genes are likely responsible for particular aspects of song system differentiation. Some of these genes may be on the Z-chromosome; candidates are currently under investigation. Importantly, although TBCA does not appear to be regulated by E2, and it does not modulate the effects of E2 in the brain, other Z-genes may interact with this hormone to influence masculinisation of the song system. Tyrosine kinase receptor B (TrkB), the high affinity receptor for BDNF, is one possibility. Expression of both the ligand and receptor in the song system is sexually dimorphic and modulated by E2 (29,52). Finally, not only is it possible that multiple Z-genes influence masculinisation, but W-genes, which are specific to females, may facilitate feminisation. The present work represents an initial series of steps in determining the role of sex chromosome genes in the development of brain and behaviour. These ideas must now be investigated more broadly.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the present study was provided by NIH R01-MH096705. We thank Dr Yu Ping Tang and Camilla Peabody for technical assistance.

References

- 1.Wright CL, Schwarz JS, Dean SL, McCarthy MM. Cellular mechanisms of estradiol-mediated sexual differentiation of the brain. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:553–561. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy MM, Arnold AP. Reframing sexual differentiation of the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:677–683. doi: 10.1038/nn.2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiner A, Perkel DJ, Mello CV, Jarvis ED. Songbirds and the revised avian brain nomenclature. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1016:77–108. doi: 10.1196/annals.1298.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wade J, Arnold AP. Sexual differentiation of the zebra finch song system. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1016:540–559. doi: 10.1196/annals.1298.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenowitz EA, Margoliash D, Nordeen KW. An introduction to birdsong and the avian song system. J Neurobiol. 1997;33:495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordeen E, Nordeen K. Sex and regional differences in the incorporation of neurons born during song learning in zebra finches. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2869–2874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02869.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirn JR, DeVoogd TJ. Genesis and death of vocal control neurons during sexual differentiation in the zebra finch. J Neurosci. 1989;9:3176–3187. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-09-03176.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordeen E, Grace A, Burek M, Nordeen K. Sex-dependent loss of projection neurons involved in avian song learning. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:671–679. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson F, Bottjer SW. Afferent influences on cell death and birth during development of a cortical nucleus necessary for learned vocal behavior in zebra finches. Development. 1994;120:13–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akutagawa E, Konishi M. Two separate areas of the brain differentially guide the development of a song control nucleus in the zebra finch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12413–12417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson F, Hohmann SE, DiStefano PS, Bottjer SW. Neurotrophins suppress apoptosis induced by deafferentation of an avian motor-cortical region. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2101–2111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-02101.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holloway CC, Clayton DF. Estrogen synthesis in the male brain triggers development of the avian song control pathway in vitro. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:170–175. doi: 10.1038/84001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wade J, Arnold AP. Post-hatching inhibition of aromatase activity does not alter sexual differentiation of the zebra finch song system. Brain Res. 1994;639:347–350. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91752-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wade J, Swender DA, McElhinny TL. Sexual differentiation of the zebra finch song system parallels genetic, not gonadal, sex. Horm Behav. 1999;36:141–152. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathews GA, Brenowitz EA, Arnold AP. Paradoxical hypermasculinization of the zebra finch song system by an antiestrogen. Horm Behav. 1988;22:540–551. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(88)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathews GA, Arnold AP. Antiestrogens fail to prevent the masculine ontogeny of the zebra finch song system. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1990;80:48–58. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(90)90147-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agate RJ, Grisham W, Wade J, Mann S, Wingfield J, Schanen C, Palotie A, Arnold AP. Neural, not gonadal, origin of brain sex differences in a gynandromorphic finch. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4873– 4878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0636925100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoh Y, Melamed E, Yang X, Kampf K, Wang S, Yehya N, Van Nas A, Replogle K, Band MR, Clayton DF, Schadt EE, Lusis AJ, Arnold AP. Dosage compensation is less effective in birds than in mammals. J Biol. 2007;6:2. doi: 10.1186/jbiol53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wade J, Peabody C, Coussens P, Tempelman RJ, Clayton DF, Liu L, Arnold AP, Agate R. A cDNA microarray from the telencephalon of juvenile male and female zebra finches. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;138:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wade J, Tang YP, Peabody C, Tempelman RJ. Enhanced gene expression in the forebrain of hatchling and juvenile male zebra finches. J Neurobiol. 2005;64:224–238. doi: 10.1002/neu.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Y, Wade J. Sexually dimorphic expression of the genes encoding ribosomal proteins L17 and L37 in the song control nuclei of juvenile zebra finches. Brain Res. 2006;1126:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang YP, Peabody C, Tomaszycki ML, Wade J. Sexually dimorphic SCAMP1 expression in the forebrain motor pathway for song production of juvenile zebra finches. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:474–482. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomaszycki ML, Peabody C, Replogle K, Clayton DF, Tempelman RJ, Wade J. Sexual differentiation of the zebra finch song system: potential roles for sex chromosome genes. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian G, Huang Y, Rommelaere H, Vandekerckhove J, Ampe C, Cowan NJ. Pathway leading to correctly folded beta-tubulin. Cell. 1996;86:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conde C, Caceres A. Microtubule assembly, organization and dynamics in axons and dendrites. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:319–332. doi: 10.1038/nrn2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi LM, Mohr M, Wade J. Enhanced expression of tubulin specific chaperone protein a, mitochondrial ribosomal protein S27, and the DNA excision repair protein XPACCH in the song system of juvenile male zebra finches. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72:199–207. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi LM, Wade J. Sexually dimorphic and developmentally regulated expression of tubulin-specific chaperone protein A in the LMAN of zebra finches. Neuroscience. 2013;247:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agate RJ, Perlman WR, Arnold AP. Cloning and expression of zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) steroidogenic factor 1: overlap with hypothalamic but not with telencephalic aromatase. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1127–1133. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang YP, Wade J. 17β-Estradiol regulates the sexually dimorphic expression of BDNF and TrkB proteins in the song system of juvenile zebra finches. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slomianka L, West MJ. Estimators of the precision of stereological estimates: an example based on the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of rats. Neuroscience. 2005;136:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wade J. Zebra finch sexual differentiation: the aromatization hypothesis revisited. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;54:354–363. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grisham W, Lee J, Park SH, Mankowski JL, Arnold AP. A dose–response study of estradiol’s effects on the developing zebra finch song system. Neurosci Lett. 2008;445:158–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lund PE, Hunt RC, Gottesman MM, Kimchi-Sarfaty C. Pseudovirions as vehicles for the delivery of siRNA. Pharm Res. 2010;27:400–420. doi: 10.1007/s11095-009-0012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato F, Yagi T, Fujieda T, Kondo Y, Yamaguchi T, Miyata K, Kaneda Y. Hemagglutinating virus of Japan envelope vectors as high-performance vehicles for delivery of small RNAs. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther. 2013;4:178. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wade J, Schlinger BA, Hodges L, Arnold AP. Fadrozole: a potent and specific inhibitor of aromatase in the zebra finch brain. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1994;94:53–61. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1994.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian G, Cowan NJ. Tubulin-specific chaperones: components of a molecular machine that assembles the α/β heterodimer. Methods Cell Biol. 2013;115:155–171. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407757-7.00011-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaglin XH, Poirier K, Saillour Y, Buhler E, Tian G, Bahi-Buisson N, Fallet-Bianco C, Phan-Dinh-Tuy F, Kong XP, Bomont P, Castelnau-Ptakhine L, Odent S, Loget P, Kossorotoff M, Snoeck I, Plessis G, Parent P, Beldjord C, Cardoso C, Represa A, Flint J, Keays DA, Cowan NJ, Chelly J. Mutations in the β tubulin gene TUBB2B result in asymmetrical polymicrogyria. Nat Genet. 2009;41:746–752. doi: 10.1038/ng.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nolasco S, Bellido J, Goncalves J, Zabala JC, Soares H. Tubulin cofactor A gene silencing in mammalian cells induces changes in microtubule cytoskeleton, cell cycle arrest and cell death. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3515–3524. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nixdorf-Bergweiler BE. Divergent and parallel development in volume sizes of telencephalic song nuclei in and female zebra finches. J Comp Neurol. 1996;375:445–456. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961118)375:3<445::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobs EC, Arnold AP, Campagnoni AT. Developmental regulation of the distribution of aromatase- and estrogen-receptor-mRNA-expressing cells in the zebra finch brain. Dev Neurosci. 1999;21:453–472. doi: 10.1159/000017413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Acharya KD, Veney SL. Characterization of the G-protein coupled membrane bound estrogen receptor GPR30 in the zebra finch brain reveals a sex difference in gene and protein expression. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;72:1433–1446. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peterson RS, Saldanha CJ, Schlinger BA. Rapid upregulation of aromatase mRNA and protein following neural injury in the zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata) J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:317–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim Y-H, Perlman WR, Arnold AP. Expression of androgen receptor mRNA in zebra finch song system: developmental regulation by estrogen. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:535–547. doi: 10.1002/cne.11033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schlinger BA, Lane NI, Grisham W, Thompson L. Androgen synthesis in a songbird: a study of Cyp17 (17α-hydroxylase/C17,20-Lyase) activity in the zebra finch. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1999;113:46–58. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soma KK, Sullivan KA, Tramontin AD, Saldanha CJ, Schlinger BA, Wingfield JC. Acute and chronic effects of an aromatase inhibitor on territorial aggression in breeding and nonbreeding male song sparrows. J Comp Physiol A. 2000;186:759–769. doi: 10.1007/s003590000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gurney ME. Hormonal control of cell form and number in the zebra finch song system. J Neurosci. 1981;1:658–673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-06-00658.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlinger BA, Arnold AP. Androgen effects on the development of the zebra finch song system. Brain Res. 1991;561:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90754-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grisham W, Park SH, Hsia JK, Kim C, Leung MC, Kim L, Arnold AP. Effects of long term flutamide treatment during development in zebra finches. Neurosci Lett. 2007;418:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bottjer SW, Hewer SJ. Castration and antisteroid treatment impair vocal learning in male zebra finches. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:337–353. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Konishi M, Akutagawa E. Neuronal growth, atrophy and death in a sexually dimorphic song nucleus in the zebra finch brain. Nature. 1985;315:145–147. doi: 10.1038/315145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mooney R, Rao M. Waiting periods versus early innervation: the development of axonal connections in the zebra finch song system. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6532–6543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06532.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen X, Agate RJ, Itoh Y, Arnold AP. Sexually dimorphic expression of trkB, a Z-linked gene, in early posthatch zebra finch brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:7730–7735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408350102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]