Abstract

Background

Differentiating melanoma metastasis from benign cutaneous lesions currently requires biopsy or costly imaging, such as positron emission tomography scans. Melanoma metastases have been observed to be subjectively warmer than similarly appearing benign lesions. We hypothesized that infrared (IR) thermography would be sensitive and specific in differentiating palpable melanoma metastases from benign lesions.

Materials and methods

Seventy-four patients (36 females and 38 males) had 251 palpable lesions imaged for this pilot study. Diagnosis was determined using pathologic confirmation or clinical diagnosis. Lesions were divided into size strata for analysis: 0–5, >5–15, >15–30, and >30 mm. Images were scored on a scale from −1 (colder than the surrounding tissue) to +3 (significantly hotter than the surrounding tissue). Sensitivity and specificity were calculated for each stratum. Logistical challenges were scored.

Results

IR imaging was able to determine the malignancy of small (0–5 mm) lesions with a sensitivity of 39% and specificity of 100%. For lesions >5–15 mm, sensitivity was 58% and specificity 98%. For lesions >15–30 mm, sensitivity was 95% and specificity 100%, and for lesions >30 mm, sensitivity was 78% and specificity 89%. The positive predictive value was 88%–100% across all strata, and the negative predictive value was 95% for >15–30 mm lesions and 80% for >30 mm lesions.

Conclusions

Malignant lesions >15 mm were differentiated from benign lesions with excellent sensitivity and specificity. IR imaging was well tolerated and feasible in a clinic setting. This pilot study shows promise in the use of thermography for the diagnosis of malignant melanoma with further potential as a noninvasive tool to follow tumor responses to systemic therapies.

Keywords: Thermography, Infrared, Melanoma, Palpable, Cutaneous infrared thermography, Infrared imaging, Melanoma metastases, Cutaneous metastases

Introduction

Melanoma metastases are commonly identified in the skin, and may be subcutaneous or intradermal. We have observed that palpable melanoma metastases are typically warm to touch compared to surrounding skin, whether dermal or subcutaneous in location. On the other hand, benign skin lesions such as cysts, dermatofibromas, granulomas, seborrheic keratoses, epidermal inclusion cysts, and scar are routinely isothermic or hypothermic in relation to surrounding skin. Furthermore, melanoma is known to be hypervascular and hypermetabolic, with high glucose uptake for glycolytic energy generation producing heat.[1] Both hypervascularity and these metabolic aberrations may explain increased temperature in these lesions.[2,3] However, thermal findings are difficult to quantify and to document objectively by clinical exam. Imaging of infrared (IR) radiation, or thermography, can permit objective temperature measures. Thermography has been explored for imaging metastatic and primary melanomas since the 1970s, with published work suggesting that it may be helpful in diagnosis of primary and metastatic cutaneous melanomas.[3][4–8] IR thermography studies of primary melanomas suggest that lesion hyperthermia correlates with thickness of primary melanomas and that nodular primary melanomas are consistently hyperthermic.[9,10][11] Additionally, hyperthermic lesions have been associated with increased lymph node positivity.[12] The use of thermography for diagnosis or follow-up of melanoma, though, had been questioned, [13,14], and is not widely applied in the clinical setting.

If IR thermography is effective in differentiating benign lesions from malignant melanoma, it may be a useful tool to quickly diagnose subcutaneous and dermal melanoma metastases. Metastatic melanomas often lose pigmentation and can be difficult to distinguish as malignant. Furthermore, a common area for recurrence is in or near the original scar from surgery, where granulomas or nodular scar tissue can be confused with tumor, leading either to unnecessary biopsies or to delayed diagnosis of recurrence. Infrared imaging of cutaneous lesions may increase diagnostic accuracy of the clinical assessment of skin lesions in melanoma patients without morbidity and with low cost.

The primary goal of this study is to obtain preliminary estimates of the sensitivity of infrared imaging for detection of melanoma metastases as a function of diameter. We hypothesized that lesions with larger diameter will be more hyperthermic than surrounding tissue, and lesions with smaller diameter are more likely to be isothermic and therefore more difficult to detect with IR thermography. A secondary aim of this study was to obtain preliminary estimates on the specificity of IR thermography for detection of metastases, primary melanomas and nevi. An additional aim was assessment of feasibility of IR imaging in terms of time, logistic constraints and patient tolerability.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Virginia (IRB number 13564). Patients 18 and over with one or more palpable cutaneous lesions were eligible for this imaging study. Palpable lesions included known melanoma deposits, suspected melanoma deposits prior to biopsy, or nonmelanoma lesions, including benign inflammatory lesions and benign neoplastic lesions (e.g,: lipomas, epidermal cysts, dermatofibromas, or scar). Aside from squamous cell cancer and basal cell cancers of the skin, which wre included in the nonmelanoma group, all other malignancies were excluded from analysis. The study was posted publicly on the NIH clinical trials website (NCT00937690).

Lesion size stratification

Lesion assessment was stratified by lesion diameter (strata a–d): a) 0–5mm, b) >5–15mm, c) >1.5–3mm, and d) >3cm. We expected infrared detection of >50% of melanomas up to 15mm diameter, and >75% of melanomas greater than 1.5cm diameter. For strata a and b, sample sizes of 40 melanoma and 40 nonmelanoma were chosen to achieve at least 80% power to detect the specified stratum difference between the two proportions of 0.20 and 0.50 with a two-sided 5% level significance test. Similarly, sample sizes of 18 melanoma and 18 nonmelanoma achieve at least 90% power to detect a difference of 0.55 between the group proportions of 0.20 and 0.75 with a two-sided 5% level significance test. All comparisons are made within a stratum and not adjusted for comparison across strata.

Imaging procedures and scoring

Lesions were identified, and hypothermic markers were placed around each lesion in a triangulating pattern. IR images were taken using an Amber Radiance 1-T IR camera from Raytheon (Las Vegas, NV). IR images were also taken of the contralateral, unaffected side of the body for comparison, when applicable. Visual light (VL) images were also taken with a hand-held digital camera, both of the lesion and of the contralateral side. VL and IR images were co-registered using hypothermic markers to definitively identify the lesion in question. Lesion data collected included location, diagnosis, method for diagnosis (clinical or biopsy), diameter, color, and depth. Diagnosis was determined using tissue biopsy or clinical diagnosis. The clinical diagnosis needed be one in which the clinician was very confident and biopsy was not indicated clinically. Each lesion was scored by a study investigator at the time of imaging using an infrared scoring system: −1: colder than surrounding skin, 0: no difference from surrounding skin, +1: weakly hotter than surrounding skin, +2: moderately hotter than surrounding skin, and +3: dramatically hotter than surrounding skin (Figure 1). Scores of +1 or greater were considered positive.

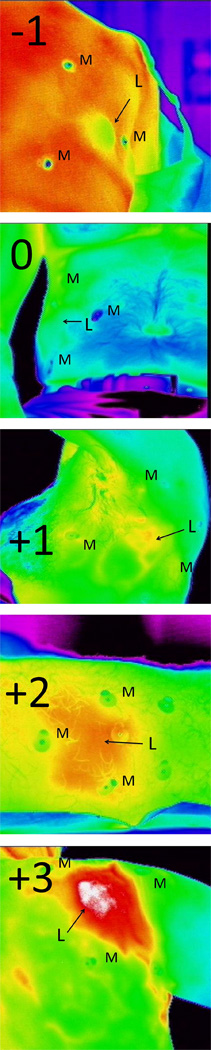

Figure 1.

A visual representation of the scoring system used in this study. M denotes the position of the metallic markers, and L is the position of the lesion. The score is used to determine the IR intensity of the lesion compared with the surrounding tissue.

Feasibility assessment

A ‘logistic questionnaire’ containing 15 questions was developed to assess investigator opinion of the feasibility and usefulness of the IR camera. Patients scored the overall tolerability of the process. Specific toxicity assessments that were scored included irritation by the skin markers, desquamation of skin at the site of the skin markers, allergic reaction to the skin markers, discomfort because of room temperature, other unforeseen toxicities, and the identification of other suspicious lesions on IR imaging not otherwise suspected. Logistical challenges scored included digital camera failure, difficulty labeling lesions, equipment availability, time available for imaging, participant willingness, markers failing to work appropriately, and heterogeneity of skin temperature leading to difficult analysis. Each of the questions was answered on a scale of 1–9 by the same surgical team for each participant with a score of 1 denoting “outstanding” and that of 9 denoting “prevented the completion of the study.” Additionally, after the conclusion of imaging, each patient was asked to score the tolerability of the imaging process. The average of these questions resulted in a participant-specific total score.

Statistics

Summary statistics including N, mean, standard deviation, and % were produced for all demographic and clinical factors, as applicable. For each stratum (0–5 mm, >5–15 mm, >1.5–3 cm, and >3 cm), the sensitivity and 95% confidence interval of hyperthermic imaging were calculated based on the available metastatic lesions. In similar fashion, the specificity of hypothermic imaging was estimated based on the nonmelanoma samples. Chi-square tests of association were performed to assess whether rates of hyperthermic lesions differed between benign and metastatic samples within each stratum. The summary statistics were produced for feasibility data.

Results

Demographics and lesion characteristics

Seventy-four patients (36 female and 38 male) had 251 lesions imaged using the infrared camera. Table 1 gives the breakdown of lesions imaged by size stratum. Median age was 58 (22–89). The vast majority of patients were Caucasian (71); there was one African-American and two of other race. Trunk lesions (117) and extremity lesions (110) were most common. Melanomas were more likely to be located on the extremities, whereas nonmelanoma lesions were more commonly on the trunk (p=0.001, Table 1). Most lesions were subcutaneous (134, 53%), although 117 were cutaneous (dermal and epidermal; 47%). Melanomas were more often subcutaneous, while nonmelanoma lesions were more commonly cutaneous (p=0.0001). Mean lesion size was 14.8mm (SD 16.5mm). 123 lesions were nonmelanoma, and 128 were melanoma. Diagnosis was obtained using either clinical diagnosis (205) or tissue biopsy (46). Biopsy type was most commonly FNA (20), followed by excisional biopsy (18), punch biopsy (6), incisional biopsy (1), and shave biopsy (1) (Table 2). Melanomas were more likely to be biopsied than nonmelanoma lesions (p=0.012). The most common nonmelanoma lesions were lipomas, seborrheic keratoses, and dysplastic nevi. These and others are listed in Table 3. Malignant lesions included both metastatic melanoma and primary melanoma.

Table 1.

Number of patients imaged per size stratum

| Stratum, mm | Non-melanoma | Melanoma |

|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | 40 | 46 |

| >5–15 | 46 | 43 |

| >15–30 | 19 | 19 |

| >30 | 18 | 18 |

Table 2.

Lesion detail.

| Nonmelanoma (n=123) |

Melanoma (n=128) |

All | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic method | Clinical | 111 | 94 | 205 |

| Excisional | 8 | 10 | 18 | |

| FNA | 2 | 18 | 20 | |

| Incisional | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Punch | 2 | 4 | 6 | |

| Shave | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Location | Extremity | 39 | 71 | 110 |

| Torso | 76 | 47 | 123 | |

| Other Face Scalp Neck |

10 7 1 2 |

8 2 6 0 |

18 9 7 2 |

|

| Depth | Cutaneous | 75 | 42 | 117 |

| Subcutaneous | 50 | 84 | 134 |

Table 3.

Breakdown of lesion diagnosis

| Lesion type | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Nonmelanoma lesions | Lipoma | 38 |

| Seborrheic keratosis | 26 | |

| Dysplastic Nevus | 21 | |

| Other | 9 | |

| Skin Tag | 7 | |

| Hemangioma | 6 | |

| Abscess | 4 | |

| Other nevus | 4 | |

| Keratoacanthoma | 3 | |

| Dermatofibroma | 2 | |

| Squamous cell cancer | 2 | |

| Actinic Keratosis | 1 | |

| Melanoma lesions | Metastatic melanoma | 126 |

| Primary melanoma | 2 |

Sensitivity and specificity of imaging

Average imaging time was 14 minutes. Representative examples of IR images obtained are in Figure 2. The sensitivity and specificity of imaging lesions of each size category are shown in Table 4. For 0–5 mm lesions, scores varied from 0 to 3 for melanomas and from −1 to 0 for nonmelanomas. For >5–15 mm lesions, scores varied from −1 to +3 for melanomas and from −1 to +2 for nonmelanomas. For >15–30 mm lesions, scores varied from 0 to +3 for melanomas and from −1 to 0 for nonmelanomas. For lesions >30 mm, scores varied from 0 to 3 for melanomas and −1 to +3 for nonmelanomas. Specificity was very high for all size lesions (89%–100%). The sensitivity was high for lesions ≥1.5 cm (95% and 78%) but was low for smaller lesions.

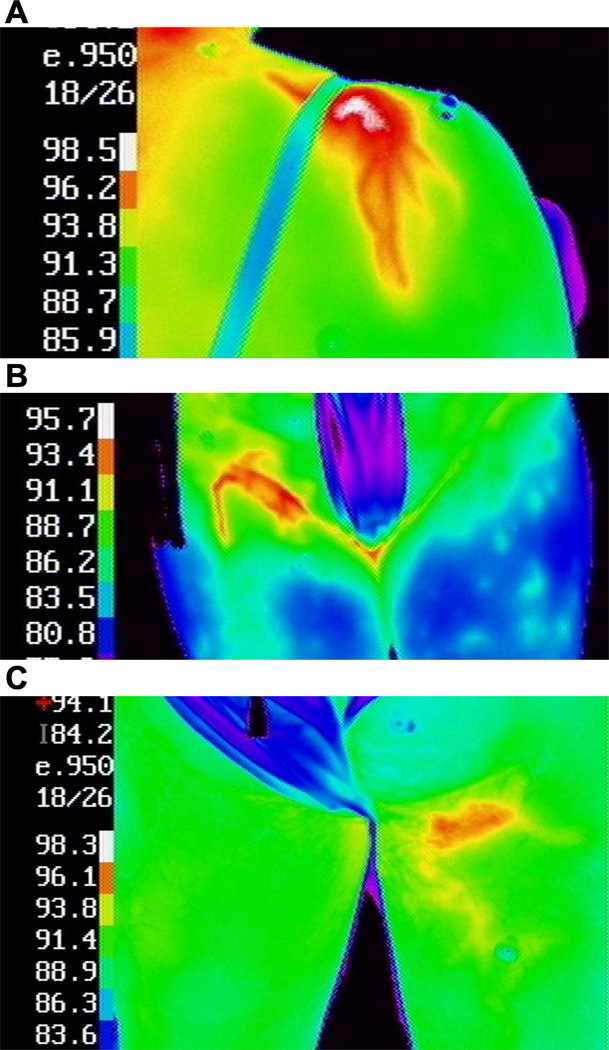

Figure 2.

Examples of hyperthermic melanoma metastases are shown (A) on the top of the left shoulder, (B) in the right groin, and (C) in the upper left thigh. The temperature (°F) for each color is shown on the left side of each image. Normothermic contralateral sites are included in images (B) and (C).

Table 4.

Sensitivity and Specificity

| Size | Specificity | Sensitivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 95% CI) | N | 95% CI | |

| 0–5 mm | 40 | 1.00 (0.91–1.00) | 46 | 0.39 (0.25–0.55) |

| >5–15 mm | 46 | 0.98 (0.88–1.00) | 43 | 0.58 (0.42–0.73) |

| >15–30 mm | 19 | 1.00 (0.82–1.00) | 19 | 0.95 (0.74–1.00) |

| >30 mm | 18 | 0.89 (0.65–0.99) | 18 | 0.78 (0.52–0.94) |

CI = confidence interval

Among lesions greater than 15mm, misclassified nonmelanoma tumors included an abscess in the 5–15 mm group and a seroma and lipoma in the >30 mm group. The misclassified malignant tumors >15 mm (all metastatic melanoma) included a subcutaneous lesion in the >15–30 mm group, three subcutaneous lesions in the >30 mm group, and one cutaneous lesion in the >30 mm group. Trunk, extremity, and other locations were represented (Table 5). The positive predictive value of IR thermography for the detection of melanoma metastases ranged from 88% to100% across the four lesion strata. The negative predictive value was low for lesions 0–15 mm in diameter but was 95% for 15–30 mm lesions and 80% for larger lesions.

Table 5.

Misclassified lesions

| Diagnosis | Size (mm) | Layer | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | MM | 18 | SQ | Torso |

| MM | 38 | SQ | Torso | |

| MM | 35 | C | Scalp | |

| MM | 55 | SQ | Extremity | |

| MM | 45 | SQ | Torso | |

| Nonmelanoma | Abscess | 14 | SQ | Torso |

| Seroma | 60 | SQ | Extremity | |

| Lipoma | 130 | SQ | Neck |

SQ= subcutaneous; C=cutaneous; MM= metastatic melanoma

Safety and feasibility of IR thermography

There were no adverse events. Operator opinion of the feasibility and usefulness of the IR camera was assessed with the logistic questionnaire immediately after each surgical case. Each question was scored on a 9-point scale, with 1 being best (outstanding and no impact on imaging) and 9 being worst (prevented the completion of the study). The mean score for overall tolerability and ease of use was 1.07 (range, 1–3 points).

Discussion

This study aimed to obtain preliminary estimates of the sensitivity and specificity of IR imaging for the detection of melanoma metastases as a function of diameter. As hypothesized, melanoma lesions with larger diameter (>15 mm) were more readily detected as hyperthermic compared with the surrounding normal tissue. Melanoma lesions with smaller diameter were not as frequently hyperthermic, although they were more often hyperthermic than nonmelanoma lesions of a similar diameter. Potential explanations for the lack of positive IR imaging with smaller lesions include limited neovascularity of smaller tumors or rapid dissipation of heat.

Another aim of this study was to obtain preliminary estimates of the specificity of IR imaging for the detection of primary and metastatic melanoma lesions. The IR imaging modality was highly specific (>85%), regardless of the lesion size. It was sensitive particularly for large (>15 mm) lesions (78%–95%). Only two primary melanomas were evaluated for this study, but the low sensitivity for the detection of small lesions suggests that IR thermography is not likely to help with the diagnosis of primary melanomas, which are typically <1 cm in diameter at the time of diagnosis.

We determined that IR imaging was well tolerated by all patients and highly feasible in a clinic setting. Imaging added an average of 14 min to each patient visit. The setup of the camera required a small area of space, and it was able to be moved with relative ease. The cost was not calculated for this study, but commercially available IR cameras are available for <$10,000. The cost of an additional 15 min of personnel time for imaging and analysis of imaging was fairly low cost. In retrospect, the use of a Likert scale running from 1 to 9 was a bit unnecessary as the vast majority of the time imaging was straightforward. We will likely modify this to a 1–5 or smaller scale in the future.

There are some limitations to the present study. The use of clinical diagnosis for most lesions could be considered a limitation, although the clinicians adhered to the standard of care and biopsied any lesion in which the diagnosis was questioned. This study was designed to enroll patients and lesions that represent a wide range of presentations, not the more limited subset for which surgical biopsy is indicated. However, given the promising findings, a valuable follow-up study may include biopsy of melanoma, to enable the assessment of histologic or gene expression correlates that may aid in defining to what extent metabolic or angiogenic processes contribute to the increased temperature of these lesions. Of particular interest is the mitotic index, which we would hypothesize would be higher in lesions that are detectable using IR imaging. Another limitation is the semiquantitative integer scale for reporting IR lesion detection, which is subject to interpretation. However, IR imaging defines a temperature for individual areas imaged; thus, in the future, it would be possible to calculate a baseline temperature for skin surrounding a lesion, from which to calculate the temperature increase in the lesion. Finally, the assessment of lesions was done by the camera operators and not based on quantitative imaging data. Further research into an automated imaging assessment would add strength to the technique and further streamline the IR imaging and assessment process.

Our encouraging preliminary data support the value of IR thermography for the diagnosis of melanoma metastases at least 15 mm in diameter. This may be useful in considering whether to do a biopsy. Other methods of diagnosis exist that are feasible in a clinic, such as fine-needle aspiration, but thermography offers an advantage of being noninvasive. Even for small lesions, the positive predictive value of thermography was very high; for larger lesions, the negative predictive value was also very high. Thus, this may be helpful for the diagnosis of clinically indeterminate lesions.

Perhaps more valuable could be its use for rapid assessment of clinical response to systemic therapy. One of the most important challenges in oncology today is the growing number of promising therapies for melanoma without efficient approaches for testing response to them rapidly. Currently, the clinical response is commonly defined by assessing changes in tumor diameter 2–3 mo after initiation of therapy, using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). For a disease that has a median survival measured in months, this dramatically reduces the number of attempts a patient has at finding an effective therapy. However, if effective, both cytotoxic therapies and new targeted therapies should induce dramatic changes in the metabolic activity and/or blood flow in melanoma deposits only hours or days after initiation of therapy. Biopsies of such tumors may be useful for the evaluation of biologic effect to predict clinical response, but less invasive methods such as IR thermography may be ideal. Positron emission tomography scanning is an appealing technology for this purpose, but its expense and radiation exposure prohibit frequent use.

In summary, this study evaluated dermal and cutaneous melanoma metastases with an IR camera, finding that lesions >15 mm were able to be differentiated from nonmelanoma lesions with excellent sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, IR imaging was well tolerated and highly feasible in a clinic setting. Finally, we see great potential of IR imaging in the assessment of tumor response to systemic therapy.

References Cited

- 1.Santa Cruz GA, Bertotti J, Marin J, Gonzalez SJ, Gossio S, Alvarez D, et al. Dynamic infrared imaging of cutaneous melanoma and normal skin in patients treated with BNCT. Appl Radiat Isot. 2009;67:S54–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.03.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Button TM, Li H, Fisher P, Rosenblatt R, Dulaimy K, Li S, et al. Dynamic infrared imaging for the detection of malignancy. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:3105–3116. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/14/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buzug TM, Schumann S, Pfaffmann L, Reinhold U, Ruhlmann J. Functional infrared imaging for skin-cancer screening. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2006;1:2766–2769. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.259895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Carlo A. Thermography and the possibilities for its applications in clinical and experimental dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:329–336. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00073-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mikulska D. Thermographic examination of cutaneous melanocytic nevi. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2009;55:31–38. discussion 38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novak OP, Bilyns'kyi BT. Thermography in the complex examination of patients with skin melanoma. Lik Sprava. 1992:66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serrano Ortega S, Garcia Mellado JV. Thermographic diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1982;73:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tapernoux B, Hessler C. Thermography of malignant melanomas. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1977;3:299–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1977.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bilynskii BT, Novak OP, Iolych MM. Use of thermography in the differential diagnosis of pigmented neoplasms. Klin Khir. 1990:28–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bilynskii BT, Novak OP, Ivantsiv RV, Iolych MM, Gubych RS. The importance of thermography in the diagnosis of oncologic diseases. Vrach Delo. 1990:95–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michel U, Hornstein OP, Schonberger A. Infrared thermography in malignant melanoma. Diagnostic potential and limits. Hautarzt. 1985;36:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michel U, Hornstein OP, Schonberger A. Thermographico-histologic study of the lymph drainage areas in malignant melanoma. Hautarzt. 1986;37:12–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cristofolini M, Perani B, Piscioli F, Recchia G, Zumiani G. Uselessness of thermography for diagnosis and follow-up of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Tumori. 1981;67:141–143. doi: 10.1177/030089168106700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diem E, Wolf G. Contact thermographic studies on primary cutaneous melanomas. Hautarzt. 1977;28:475–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]