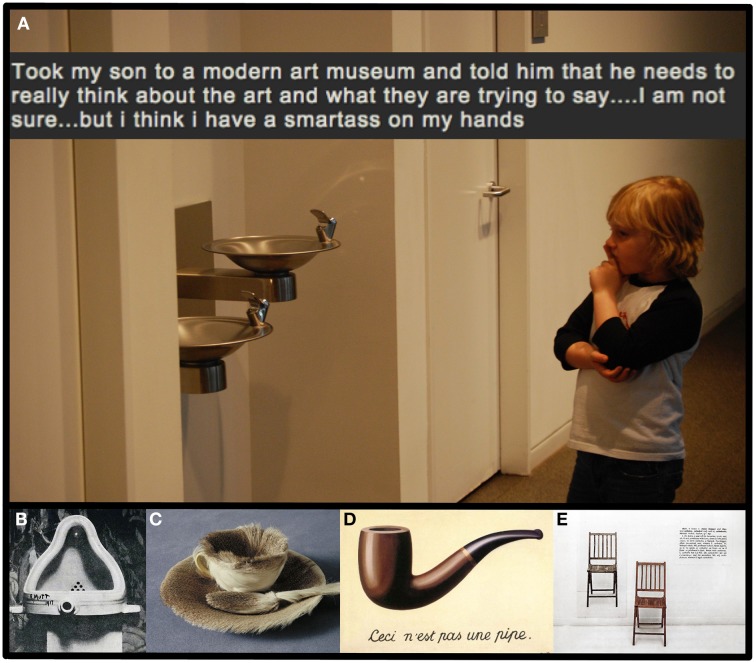

Figure 1.

The production and consumption of conceptual art tap into an interpretative stance that is older, and more basic than the genre itself. (A) Took my son to a modern art museum, Simon1972 (2013). The moment captured in this photo and caption suggests that understanding the difference between art objects and utilitarian ones-along with the critical stance associated with conceptual art-can appear relatively early in childhood. (B–E) Uses of both reduction and contrast can be seen in iconic conceptual art pieces from a variety of time periods and movements (e.g., Dada, Surrealism, Minimalism, and contemporary Conceptual art). Works like (B) Fountain by Duchamp (1917) and (C) Object by Oppenheim (1936) place simple objects in novel contexts. Whereas (D) The Treachery of Images by Magritte (1928–1929) and (E) One and Three Chairs by Kosuth (1965) assemble representations of common objects in distinct formats. The use of reduction and contrast lend themselves to meaningful visual images that are salient and psychologically digestible. (All low-resolution images of art works were obtained from Wikipedia with reproduction here constituting fair use for academic and educational purposes in an open access journal.)