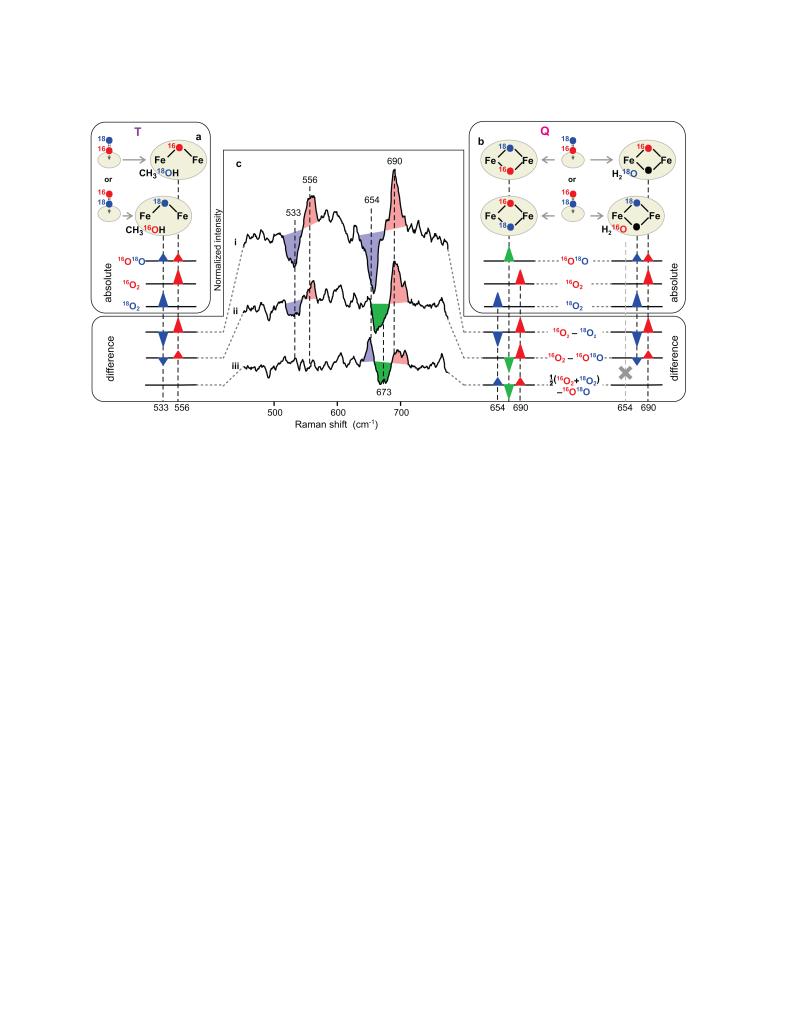

Figure 2. Fingerprinting cluster structure using 16O18O mixed oxygen isotope.

a, b, Asymmetrically labelled 16O18O can initially bind in two equiprobable orientations, yielding an even mixture of two isotopomers in T or Q (panels a and b, top) exhibiting characteristic vibrations (panels a and b, bottom). Two scenarios are possible for Q, depending on whether two (left) or one (right) O2-derived atoms (red and blue) are incorporated into the cluster. If only one atom is incorporated, then the second oxygen atom in the core structure would derive from solvent (black). Water and methanol exemplify a departing oxygen atom while other ligands are omitted for simplicity. Since the two isotopomers of T (a) and those of singly labelled Q (b, right) have identical composition as corresponding 16O2 and 18O2 derivatives, they will exhibit both vibrations simultaneously at half the intensity. Doubly labelled Q (panel b, left) will be different from both symmetrically labelled derivatives and thus, c, will exhibit a new vibration (green), as illustrated by isotope difference spectra (c). The 16O2 – 16O18O difference (ii) in singly labelled cluster (a, b right) will appear as the 16O2 – 18O2 difference (i) with reduced intensity. The 16O18O derivative will be identical to the average of symmetrical isotopomers, yielding no signal in trace iii, as observed experimentally for T. The new frequency in doubly labelled Q should appear in both difference (ii) and (iii), and can, indeed, be seen in experimental data at 673 cm−1. Spectral superimposition inflates the apparent isotopic shift when frequencies of isotopomers are close (traces (ii) and (iii), right), but not when bands are well separated (trace (i)).