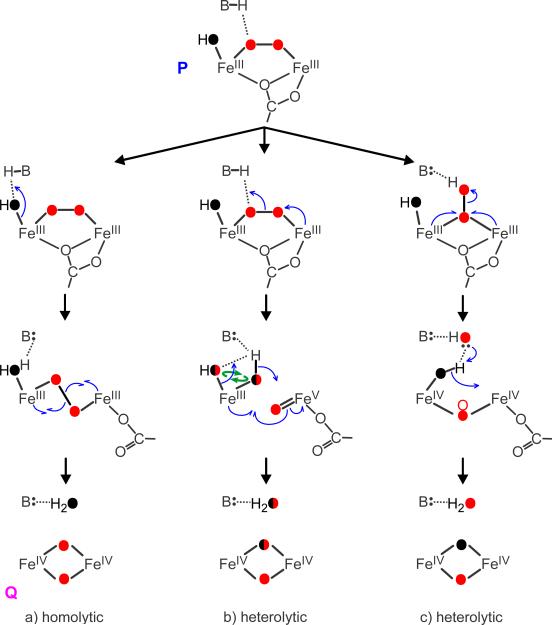

Extended Data Figure 5. Potential O-O bond cleavage mechanisms in the dinuclear centre of MMO.

The most divergent mechanisms are shown along with expected isotopic composition of oxygen derived from O2 (red) and solvent (black). All mechanisms are triggered by proton-dependent rearrangement of P10,33. The monodentate carboxylate bridge (E243) found in the diferrous enzyme34 is likely to maintain this position in P, but return to the non-bridging position in Q, as found in the resting enzyme, to accommodate the diamond core structure. The catalytic base B, which mediates proton dependency, has not been definitively identified. Based on structural similarity to other di-iron O2-activating enzymes and DFT computations for P-analogues in those systems11,35,36, we have proposed11 that E114 (a ligand to solvent-coordinated iron in P), is this base. Other ligands not directly involved in cleavage are omitted for clarity (see Fig. 3). Equal intensities of Q-16O2 and Q-18O2 modes, and the absence of Q-16O18O mode in Fig. 2c, (i) argue against isotope scrambling in Q formation. This and all other experimental results reported to date are in full accord with the nominally concerted homolytic cleavage mechanism. We postulate that the loss of E243 bridge facilitates the conversion of cis-μ-peroxo adduct in P to the trans-μ-peroxo conformation and the ensuing O-O bond cleavage (a) to form the diamond core structure detected here. This transition is supported by DFT computations37. In contrast, the stepwise, end-on heterolytic cleavage mechanism (c) (analogous to formation of compound I in cytochrome P450) leads to the mixed isotope cluster in Q-18O2 and can be ruled out. Heterolytic cleavage of trans-μ-peroxo is essentially isoelectronic to and experimentally indistinguishable from the homolytic mechanism (a). The proton-assisted heterolytic cleavage of cis-μ-peroxo bridge (b) cannot be ruled out yet, but several observations argue against it. (1) We did not observe isotope scrambling (curved green arrows), which is expected upon formation of two terminal oxygenic ligands on the same iron. While scrambling may not occur if ligands are highly stabilized, structural basis for such putative stabilization is not apparent. Scrambling may also not be observed if formation of diamond core is fast following bond cleavage, in which case mechanism (b) becomes, in essence, a stepwise, proton-assisted homolytic cleavage, also indistinguishable from (a). (2) Two iron atoms in di-ferric P and di-ferryl Q are in the same oxidation states and in indistinguishable electronic environments2,20. Such symmetry is unfavourable for O-O bond polarization and charge separation in the FeIII/FeV state during heterolytic cleavage. The deprotonated state of the peroxo bridge in P also argues against overall polarity of the site that would aid heterolytic cleavage.