Abstract

In statistics, pattern recognition and signal processing, it is of utmost importance to have an effective and efficient distance to measure the similarity between two distributions and sequences. In statistics this is referred to as goodness-of-fit problem. Two leading goodness of fit methods are chi-square and Kolmogorov–Smirnov distances. The strictly localized nature of these two measures hinders their practical utilities in patterns and signals where the sample size is usually small. In view of this problem Rubner and colleagues developed the earth mover’s distance (EMD) to allow for cross-bin moves in evaluating the distance between two patterns, which find a broad spectrum of applications. EMD-L1 was later proposed to reduce the time complexity of EMD from super-cubic by one order of magnitude by exploiting the special L1 metric. EMD-hat was developed to turn the global EMD to a localized one by discarding long-distance earth movements. In this work, we introduce a Markov EMD (MEMD) by treating the source and destination nodes absolutely symmetrically. In MEMD, like hat-EMD, the earth is only moved locally as dictated by the degree d of neighborhood system. Nodes that cannot be matched locally is handled by dummy source and destination nodes. By use of this localized network structure, a greedy algorithm that is linear to the degree d and number of nodes is then developed to evaluate the MEMD. Empirical studies on the use of MEMD on deterministic and statistical synthetic sequences and SIFT-based image retrieval suggested encouraging performances.

Keywords: Goodness-of-fit, earth mover’s distance, linear programming, greedy algorithm, pattern matching, content-based image retrieval

1. Introduction

In statistics, pattern recognition and signal processing, and indeed in all fields where statistics has a role to play, e.g. industry, agriculture and bio-medical studies, an effective and efficient distance that can measure the similarity and/or dissimilarity between two distributions, patterns or sequences is of utmost importance. In statistics, to see if two distributions originate from the same source is referred to as goodness-of-fit problem.1 The corresponding test is called test of fit. Two leading methods are χ2-test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The former adds up the L2 distance between two distributions in each bin normalized by the expected bin size, namely,

| (1) |

where ni0 and ni1 are the counts of observed values in bin No. i for distribution 0 and 1, respectively. The latter uses the maximum absolute difference between the corresponding bins of the two cumulative distributions F0 and F1:

| (2) |

These two tests of fit are so important that in most textbooks on statistics, e.g. Refs. 1 (Chap. 25) and 2 (Chap. 10), when the topic of goodness of fit is introduced, only these two measures are discussed. In cases where the large sample size can be obtained the efficacy of these two measures has been mathematically proved and practically confirmed time and again by real world industrial/agricultural/biomedical applications for decades.3

However, in pattern recognition, signal processing, especially image processing and computer vision, with relatively small sample size (N ≪ ∞) and universal presence of rampant noises, the literal application of these two measures is problematic. As a matter of fact, even the bin number i’s for different distributions cannot be assumed to be well aligned. A brief look of the definitions of these two monumental tests of fit, Eqs. (1) and (2), can reveal the fact that the possible mis-matches of bin indexes will cause great trouble to the applicability of these two measures, where the precise bin-wise deviations are the actual bed-stone of the distance measures. Conversely, to address the noise present in these subjects, cross-bin deviations should be taken into account. To answer for this need, Peleg and colleagues4 first introduced linear optimization to gauge the similarity between two gray-scale images in 1989. Mumford5 laid out the foundation for what is needed to measure the perceptive similarity between two shapes and pointed out the usefulness of the Monge–Kantorovich mass transportation distance to this end. In 2000, based on the transportation problem in discrete linear programming6 Rubner and colleagues formulated the earth mover’s distance (EMD), which is the actual discrete version of the Monge–Kantorovich distance.7 Instead of focusing only on corresponding bins between two distributions, or generalized by Rubner et al. as signatures, the counts in each bin being treated as earth or pebbles that can be moved around, the EMD endeavors to find the minimal cost of moving the earth/pebbles from the source signature p to the destination signature q. Formally, let p = {(pi, wpi), i = 1, …, m}, and q = {(qj, wqj), j = 1, …, n}, where the former component pi(qj) is the cluster representative, the latter one wpi (wqj) betokens the weight of cluster pi(qi). Denoting the earth moved from bin i of P to bin j of Q by flow fij, and distance between these two bins as dij, let flow matrix F = [fij], the corresponding transportation problem is then formulated as below:

| (3) |

subject to the following constraints:

- Constraint 1. All flows must be non-negative:

- Constraint 2. Total flow out of source i cannot be larger than its total capacity wpi:

- Constraint 3. Total flow to the destination j cannot be larger than its request wqj:

- Constraint 4. Overall flow must be as large as possible:

Equipped with the optimal flow matrix F, the EMD(p,q) is then defined as the weighted distance normalized by the entire flow:

| (4) |

The problem as formulated in Eq. (3) together with the four constraints is an actual special type of linear programming problem, namely the transportation problem that was discussed in great detail in Chap. 7 of Ref. 6. Instead of applying the general simplex tableau or the interior point method, the the special layout of the constraints can be effectively exploited to arrive at the more efficient transportation simplex method in search of the optimal flow matrix F, which is an algorithm with time complexity of super-cubic, i.e. O(n4 ∩ n3). This flexibility of matching cross-bin values is of crucial interest in pattern recognition, signal processing and related subjects. EMD consequently was employed widely in a great array of successful applications, such as Refs. 8–12, just name a few.

In spite of its immense success, the EMD suffers from two shortcomings:

Immense time complexity: For problems of small or medium size the super-cubic time complexity is acceptable. However, for practical problems in this Internet era n can easily approach millions and larger. The computational burden levied by EMD evaluation is prohibitive. For instance, for an ordinary gray-scale image, the corresponding number of SIFT descriptors (with typical dimension 128),13 one of the most influential visual feature descriptors, is usually at least 200 to 300. If one uses EMD, to decide the similarity between two images several minutes are needed.a If one then wants to find the match in an even small-sized image database with say 100 images for one query image, the time needed has to be measured in weeks, if not months, which is clearly unacceptable for practical use.

- Global cross-bin matching: EMD tries to match two signatures p and q by moving earth from p to q across all possible bins. Constraint 4 dictates that all possible earth must be moved in this matching procedure, regardless of the amount of efforts that are involved. As an extreme example, for two vectors p and q of dimension 256, suppose p is all zeros except the leading element being 1, whereas q is all zeros except the trailing element of value 1, that is,

According to the linear optimization of the EMD, the earth of amount 1 in the first position of p must be moved all the way to the last position of q to fill in the “hole” of the same capacity. The resultant distance normalized by the amount of earth is 255, the distance d0,255 traveled by this movement. This global cross-bin matching dictated by EMD failed to reflect the perceptive similarity between these two vectors as discussed by Mumford5: perceptively p and q are extremely similar except two minor noise at both ends. In this regard, a simple L1 or L2 does a better job, which results in distance 2 and , respectively. Furthermore, as first pointed out by Pele and Werman in Ref. 14 the normalization defined by EMD as dictated by Eq. (4) is also problematic: if one changes the value 1 in both p and q to say 1000, the corresponding EMD is of the same value 255, which is counter-intuitive.

Given the conceptual advantage provided by the EMD framework, in the last decade since its invention sustained efforts have been made by several groups of researchers to combat these two drawbacks.

In Ref. 15, by taking advantage of the special metric nature of the L1 distance, Ling and Okada proposed the EMD-L1 distance that effectively reduced the time complexity of the original EMD from super-cubic to O(n2). Impressive experimental results on image retrieval and shape matching were reported thereof. One drawback of this method is its use of L1 that may not be appropriate for many practical situations where metrics are more desirable. For instance, in the real world commodity transportation or air travel planning systems, L2 could be the more preferable choice. Furthermore, the global nature of EMD remains unchanged. Shirdhonkar and Jacobs developed an approximate EMD in linear time for low dimensional histogram by using wavelet transform.16 This method suffers from the fact that it yields approximate EMD (with elegant bounds though) and good for lower-dimension histogram data only. Like EMD-L1, nothing is done to rein in the global nature of EMD. In a recent paper,17 Li and colleagues developed a sparse representation-based EMD for matching probability density function, which is more efficient and robust than the conventional EMD. Consistently promising results have been achieved for image retrievals and texture classification.

In a series of papers,14,18 Pele and Werman endeavored to enhance EMD with great insights to address both drawbacks of the EMD framework. Instead of allowing earth to be moved globally, in their the ground distance is thresholded by a prescribed degree d, that is, in the optimization process for each bin i in P, only those bin j’s in Q where dij ≤ d are taken into account. Unmatched earth are simply levied cost d. The corresponding target function, in place of Eq. (3) for the definition of EMD, to be minimized in is as below14:

| (5) |

the four constraints required by EMD stay as is. The mover in this new EMD is essentially a lazy one: any earth movement with distance longer than d is not attempted, instead a constant penalty is applied. Lazy as we may call it, a more reasonable distance is resulted by this laziness. In our afore-mentioned example p and q, where EMD-L1(p, q) = 255, according to this new definition , a far more reasonable similarity measure. As can be seen from Eq. (5) the overall distance is not normalized by the sum of fij any more, as done by EMD, c.f., Eq. (4). If we now change the singular non-zero value in p and q from 1 to 1000, the resultant is 1000d, which correctly represents the dissimilarity between these two vectors. Depicted as a network as done in operations research19 and network flow studies,20 the optimization invoked by EMD corresponds to a bi-partie network where there is an edge between each and every source node p ∈ P and destination node q ∈ Q, as shown in Fig. 1(a). While the network for is illustrated in Fig. 1(b), similar to Fig. 1 of Ref. 18. The number of connecting edges for is clearly smaller than that for EMD by order n. As a matter of fact, by calling the successive shortest path (SSP) algorithm (Chap. 9 of Ref. 20), a variant of the Ford–Fulkerson algorithm21 that successively runs the celebrated Dijkstra’s shortest path search procedure from the grand source node S to the final sink node T in search of the minimal flow, if one uses e.g. Fibonacci heap, the time complexity of SSP is in theory O(n2 log n).b Unlike EMD where it takes more than 6 hours just to evaluate the distance between the SIFT descriptors of two 256 × 256 gray-scale image, the time used in the computation of the corresponding is on average 21.55min,c a considerably reduced time complexity. However, to find a match in a 100-image small DB, several days are still needed. Therefore, to render this new EMD practical, an O(n2 log n) algorithm is not a viable solution, yet more time complexity reduction is definitely needed. SIFTDIST was further developed by Pele and Werman14 to exploit the special layout of SIFT orientation histogram, thus resulting in a procedure of time complexity linear to n.

Fig. 1.

Network structure for EMD (a), (b) and MEMD (c). Notations: •: original source and destination bins; ■: additional nodes needed in the optimization process. The singular grand source node S and grand destination node T are added to facilitate optimization procedures such as successive shortest path and most minimum flow algorithms.

By introducing the concept of thresholded ground distance, tackled the global nature of EMD and reduced the time complexity by order of magnitude, which as a result significantly expanded the usefulness of the EMD, it is therefore a major development within the EMD family. It resolved counter-intuitive distances between two signatures arrived at by the EMD, it however has its own problems for other instances. As discussed before,

which is resulted by moving the 1000 earth from the first position of vector p to the last position of vector q by the thresholded ground distance d, not 255 as dictated by EMD. This distance is a perfectly reasonable similarity measure between these two vectors. However, according to the mathematical formulation of , c.f., Eq. (5), we also have the following distance value:

that is, if we change the last element of q from 1000 to 0, we obtain the same distance, which was not caused by moving the earth around, but by the second term of the right-hand side of Eq. (5): α |∑i pi − ∑j qj |d when α = 1 as suggested by the authors of Ref. 18. Intuitively the second distance should be smaller than the first one. Indeed if one sets α < 1, this desired smaller value can be achieved, which is then 1000 αd. However, by setting α < 1 the benefit it generates is worse than the troubles it may cause. Consider the next distance according to d:

due to the fact that the non-zero bin in q″ is outside the thresholded ground distance. The much larger magnitude of than that of is undesirable now: we can move the amount of 1000 from p to q″ by ground distance 2, this effort should not be larger than when p has extra earth of amount 1000. That is probably the reason why the authors carefully set the default value of α at 1 in their papers and implementations, which conforms to the thresholded ground distance elegantly: the efforts involved when there are extra or deficit earth between the source and destination nodes are the same as those made by moving earth more than the threshold ground distance.

Now that there is no choice but fixing α at 1, another strange distance given by demonstrates itself:

where the last value x in vector q‴ is any value in-between [0, 1000]. That is, whatever value x assumes in q‴, its distance to p is the same. In this situation certainly has much to be desired. Interestingly, in these situations the seemingly simplistic L1 and L2 distances make more sense, i.e. L1(p, q‴) = 1000+x, whereas .

The foregoing example is an over-simplified example just to reveal the difficulty faced by the original EMD and , this undesirable behavior is even more severe in more complex applications. In light of the pros and cons of the original EMD and, by using the technique of additional dummy source and destination nodes in linear optimization,6 we propose a new transportation flow minimization formulation within the linear programming framework with the network configuration illustrated in Fig. 1(c). The corresponding distance is referred to as Markov EMD (MEMD), the fact that it is an actual metric can be proved mathematically. The prohibitive processing time required by linear programming procedure, be it simplex tableau, Karmarkar’s interior point approach6 or Barrier methods of nonlinear optimization methods (Chap. 16 of Ref. 22), renders it a necessity to exploit the special topology of our MEMD in order to significantly curtail the processing time. Toward this end a greedy procedure to evaluate the MEMD with the desired linear time complexity is developed and statistically established. This novel localized EMD that can effectively reflect the similarity between two signatures and meanwhile be evaluated within O(n) is of great interest in measuring the similarity between two distributions, patterns and sequences.

This paper is organized as below. The MEMD is introduced in Sec. 2. Section 3 presents the greedy algorithm to evaluate the MEMD between two sequences. Section 4 presents empirical evidences for the efficacy of MEMD by token of synthetic as well as real world examples. We conclude this paper with more discussions and remarks in Sec. 5.

2. Formulation of Markov Earth Mover’s Distance

In this section, the new MEMD is first introduced as a transportation problem with additional dummy source and destination nodes. Several propositions are established to indicate the mathematical properties of the MEMD. Issues regarding the computation of MEMD are addressed in Sec. 2.1.

2.1. MEMD as a transportation problem with dummy source and destination nodes

Transportation problem is one of the most important types of linear programming problems that have been widely employed in industry and military applications.19,20 It concerns itself with the determination of optimally transporting goods from sources p to destinations q under a certain set of constraints such as the four constraints for EMD. Two assumptions, following the notations used in the formulation of EMD in Eq. (3), are made in the transportation problem model:

Requirements assumption: Each source has a fixed amount of supplies, while each destination has a fixed amount of demands, namely, all wpi’s and wqj’s are of fixed values.

Cost assumption: The cost of transporting units from a source to a particular destination is in direct proportions to the number of transported units. This unit transportation cost form pi to qj is denoted by d(i, j).

The corresponding wpi, wqj and dij are the actual set of parameters for the transportation problem model.

The transportation problem model is then formulated as below:

| (6) |

subject to the following constraints:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

which are similar to the first three constraints dictated by EMD, only the inequalities in EMD are replaced by equalities.

In order for a transportation problem model to have a solution, the following property should be satisfied, which has been mathematically established in operations research:

Feasibility solutions property

A transportation problem has a feasible solutions if and only if the equality below holds true:

| (10) |

In the formulation of EMD as given in Sec. 1, when an additional dummy destination node d, as shown in Fig. 1(a), is added to enforce the foregoing feasibility property. Mathematically the addition of either a dummy source node or a dummy destination node is dictated by the fourth constraint of EMD, i.e. the total flow is the smaller value of total supplies and total demands. The inequalities present in the first three constraints are caused by this additional special constraint dictated by EMD. The constraints 2–4 for this case of EMD can be rewritten into equality constraints in the same vein as Eqs. (8) and (9) in the standard formulation of transportation problem model as below:

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

where the wid is the earth transported from supply node i to the dummy destination d, Eq. (13) is essentially an equivalent re-formulation of constraint 4 of EMD.

Conversely when a dummy source s node can be added and the equality constraints can be given in a manner similar to Eqs. (11)–(13). No dummy node is needed when .

The special structural property of the source and demand constraints present in the transportation problem model entails a streamlined simplex method, the so-called transportation simplex method, which significantly strikes out the time complexity required by the general simplex tableau method. As reported by Rubner et al.,7 the corresponding time complexity is super-cubic O(n3 ∩ n4), already a major improvement over general simplex method.

Whereas in one dummy source and one dummy destination node are added, which essentially guarantees the existence of the optimal solution to the linear programming problem. There is however a main structural changes in the formulation of though: the connection between pi’s to the node r and node d to qi’s as illustrated in Fig. 1(b) disqualifies the as a transportation problem, indeed as pointed out by Pele and Werman,18 the optimization involved in the evaluation of between two signatures is now a transhipment problem,20 a close cousin of transportation problem under the class of minimum flow problem in general combinatorial optimization.23 Consequently the additional nodes r and d introduced by are not strictly dummy source and destination nodes used in the transportation problem model. The resultant network of is not a bi-partie graph any longer. By successively calling Dijkstra’s procedure to find the shortest path from the grand source S to the grand destination T over the current augmented network as dictated by the Ford–Fulkerson method, which is the SSP algorithm, the time complexity to compute is reduced to O(n2 log n).

The addition of dummy source and destination nodes widely exercised in operations research is targeted to satisfy the feasibility property of transportation problem model, as done by EMD. In EMD, the earth is allowed to be transported globally from all source bin i to destination bin j, thus resulting in the complete bi-partie connection in Fig. 1(a). If we want to introduce the localization as achieved by , then the links whose unit costs, or ground distance in the EMD notation, are larger than a prescribed threshold d are removed. Any extra supplies in qi that cannot be transported to its local adjacent destination bins qj’s are then dumped to the dummy destination node D2 depicted in Fig. 1(c). Similarly any un-satisfied demands asked for by destination bin qj is virtually satisfied by taking corresponding earth units from the dummy source bin D1 (Fig. 1(c)). The transportation cost u = d(i, D2) is set at a value larger than the ground distance threshold d or else the minimization effort made by Eq. (6) will prefer to move earth units to the dummy bin D1 first, likewise we have υ = dD1,j > d. Although in theory u and υ can be different, in our experiments we set u = υ = c for simplicity.

The amount wD1 of supplies for the dummy source bin D1 is set at , while wD2 of the demands for the dummy destination bin D2 takes the value of . Therefore the feasibility property is naturally satisfied, i.e.

| (14) |

Hence the optimal solution for this localized transportation problem model is in theory guaranteed. We denote it by MEMD due to the fact that only localized transportation is taken into account in the evaluation of this distance. The network geometry of MEMD is diagrammatically demonstrated in Fig. 1(c). The grand source S and destination D are added to ensure that there is only one source and destination that is conveniently assumed in most minimal flow algorithm, such as SSP and Ford–Fulkerson algorithm.20 As a result, pi’s/D1 and qj’s/D2 are no longer treated as source and destination bins, respectively, but as regular intermediate nodes now. All supplies are uniquely assigned to S, while all demands are given to D. Due to this formulation, the supplies provided in S and demands requested by T are both the total sum of original wpi’s and wqj’s, namely, the total flow T as defined in Eq. (14). The feasibility property of transportation problem model is thus still satisfied.

One necessary information that must be provided for any transportation problem model is the cost assignment table. In MEMD the distance d(i, j) between regular bins pi and qj can be any metric system as long as the properties of a metric distance is satisfied,24 namely, d(i, i) = 0, d(i, j) = d(j, i), d(i, j) ≤ d(i, k) + d(k, j). For the additional structural nodes S, D, D1 and D2, the costs on involved edges are defined as below:

| (15) |

The costs for those non-linking pairs of nodes are set to ∞. The resultant cost matrix is denoted by C.

To facilitate the ensuing optimization procedure, the maximal units, referred to as the capacity, that can be transported on all links should be assigned. The capacities of the edges from S and to D are set at their given fixed supplies or demands, namely,

| (16) |

| (17) |

For edges linking bin pi in p and qj in q,

| (18) |

The reason why cij is assigned the larger one between wpi and wqj is due to the fact that although the original flow direction is from pi to qj, in the middle of minimal flow algorithm such as SSP and Ford–Fulkerson method the augmenting path may reverse the direction in search of an optimal solution, the capacity of the connecting edge should thus be set at the maximal value of the two values. One desirable side effect of this capacity assignment is that it renders the resultant network symmetric, that is, if one reverses the original flow direction from D to S, the capacity values are the same. As will be seen shortly, this symmetry has a positive role to play in our justification of the fact that MEMD is a metric distance.

For edges associated with the dummy source D1 and dummy destination D2:

| (19) |

The flow in-between D1 and D2 is at most min{wD1, wD2}, its capacity is hence assigned accordingly. Again if one reverses the roles played by D1 and D2, the corresponding capacity assignment remains unchanged, which is of importance in establishing the metric property of MEMD. If there is no edge connecting two bins x and y, the corresponding capacity is then set to 0. These capacity values are gathered in a capacity matrix C.

Summarizing, the conceptual evaluation of the MEMDd(p, q) between two given signatures or patterns p and q for a prescribed degree d goes through the following steps:

Add auxiliary nodes S, D, D1 and D2 to form the network dictated by the degree d, as shown in Fig. 1(c).

Form the capacity matrix C as determined by Eqs. (16)–(19), and cost matrix D as defined in Eq. (15).

- MEMDd(p, q) is defined as the minimal cost of the flow fij weighted by the corresponding cost d(i, j), i.e.

subject to the following three constraints(20) (21) (22)

cij and d(i, j) are the elements of capacity matrix C and cost matrix D, respectively.(23)

We are now ready to establish the desirable properties of MEMD.

Proposition 1

MEMD is feasible.

Proof

The total flow constraint satisfies the feasibility property of transportation problem model, the optimization process involved in the MEMD computation is therefore feasible.

Next we establish the metric property of MEMD.24

Proposition 2

MEMD is a metric distance.

Proof

(1) Reflectivity:

| (24) |

If p = q, then m = n and wpi = wqi, by transporting all units from pi to qi, noticing that dij = 0 if and only if i = j due to the metric nature of d(·, ·), the overall cost is precisely 0.

If MEMD(p, q) = 0, all supplies in p must be transported to q with 0 cost, and all demands of q must be satisfied through 0 cost transportation. Therefore m = n and wpi = wqi which results in p = q. Equation (24) is thus justified.

(2) Symmetry:

| (25) |

By carefully checking the definitions of the capacity assignments, c.f., Eqs. (16)–(19), the capacity values are symmetric, namely, cx,y = cy,x for all possible edges xy in the configuration of MEMD. Furthermore, the cost d(x, y) is also symmetric, d(x, y) = d(y, x) due to the metric nature of ordinary dpi,qj and structural nodes defined in Eq. (15). To evaluate MEMD(q, p) what is needed is simply reverse the roles played by S and D, pi and qj, D1 and D2, the symmetry of both capacity function c·, · and cost function d(·, ·) assures the equivalence of these two networks. We thus substantiated Eq. (25).

(3) Triangular inequality:

| (26) |

According to the optimization involved in MEMD, MEMD(s, t) is the minimal cost subject to the three sets of constraints, i.e. Eqs. (7)–(9). While the distance MEMD(p,w) + MEMD(w, q) on the right-hand side of Eq. (26) can be viewed as finding the MEMD(p, q) with the normal three constraints plus one additional constraint: an intermediate signature w must be matched in the optimization process. This additional constraint will increase the minimal value that can be attained by the linear optimization in evaluating MEMD(p, q). Equation (26) hence holds true.

The preceding three items formally proved that MEMD(·, ·) is a metric distance.

2.2. Computation of MEMD

The MEMD formulated in the preceding subsection can be viewed as a standard linear programming problem whose evaluation can be achieved in most popular computational software packages. For instance, by simply filling out the equality constraints based on supply and demand constraints, one can call linprog provided by the optimization toolbox in Matlab to obtain the MEMD. However, the time complexity due to the general linear programming procedure call is prohibitive. It takes linprog of Matlab r2007b on a 2.20GHz Pentium 0.61 s to evaluate the MEMD2(p, q) for two 128-dimension vectors p and q.

This high computational cost in a general linear programming procedure was well taken by researchers in mathematical programming. By exploiting the special structures involved in the transportation problem model, a streamlined transportation simplex method is developed which eliminates almost all the simplex table (Chap. 8 of Ref. 19). This was employed in Rubner et al.’s original EMD computation with reportedly super-cubic time complexity.7 For the same two 128-dimension vectors on the same machine with the same version of Matlab, the EMD evaluation only needs 0.07 s, an impressive reduction of processing time indeed.

The transportation tableau method is further improved by ,14,18 where the ground distance was thresholded, where, as seen in Fig. 1(b), the number of edges are reduced from O(n2) to O(n), to order dn to be more precise, d is the threshold. The SSP20 can then be called upon to effect a time complexity of O(n2 log n). For two 128-dimension vectors, based on Pele’s FastEMD-2 implementation, the processing time is reduced to 0.013 s on the same machine with the same Matlab version. By exploiting the special L1 metric, EMD-L1 delivered an EMD computation with quadratic time complexity O(n2). The evaluation of the same two 128-dimension vectors costs EMD-L1 0.0048 s under otherwise exactly the same condition based on the software provided by the authors.e Although the theoretical time complexity of and EMD-L1 differs only by a factor of log n, the overhead in the maintenance of the Fibonacci heap popularly used in the implementation of SSP is indeed quite costly, which explains why the actual time difference between and EMD-L1, 0.013 vs. 0.0048, is more than the theoretical logarithmic factor.

The SSP can be easily plugged in the evaluation of MEMD as done by , each iteration finds the shortest path from S to D by Dijkstra’s greedy procedure and the augmenting path is then added, which reversed the recorded flow direction with the same amount of flow just discovered, for the preparations of the next search of shortest path. Given that the MEMD is a special case of transshipment problem, the optimality of SSP as firmly established by Ahuja et al.41 results in the following proposition regarding the evaluation of MEMD.

Proposition 3

MEMD is evaluated correctly by SSP.

The time needed by MEMD2 for the same two 128-dimension vectors under the same computational resources is 0.012 s, somewhere between and EMD-L1 but much closer to the former: After all in theory the SSP for MEMD should be of the time complexity O(n2 log n).

3. Greedy Approximations of MEMD

In this section, two greedy procedures, GAM and apx, to evaluate the MEMD in a time complexity O(n) are first developed. We next perform a Monte Carlo study to gain insights into the degree of approximations that can be attained by these two approximation algorithms.

3.1. Greedy approximation algorithms of MEMD

As briefly discussed in Sec. 1, to make practical use of the similarity measure between signatures/patterns, where both the dimensionality of the descriptors and the number of the descriptors combined can give rise to a problem where the size n can easily exceed the order of tens of thousands and even more, e.g. the SIFT signature for an ordinary gray-scale image with a mere size 256 × 256 “Lena” sets n at about half million (375 × 128 = 48 000). The O(n2 log n) time complexity is then measured at least in terms of billions that is not ignorable even for the fastest computers, thus causing trouble for its practical utility. A search that can only be answered after several hours or days by a system is certainly not attractive. Consequently more work needs to be done to further reduce the processing time, despite the immense computational power of the current computers.

In Ref. 14, by taking advantage of the special circular neighborhood system used in the SIFT orientation histogram, SIFTDIST was developed to deliver the linear time complexity, which was achieved by incrementally saturate the links in the ascending order of their associated costs. For general , given its nonbi-partie nature and relatively complex connections as seen in Fig. 1(b), no linear time computation was proposed by its inventors. In MEMD, given its strict bi-partie feature and localized connections in the absence of any loops or circular links, a greedy approximation procedure is developed next to attain a time complexity linear to the possible number of edges between pi, D1 and qj, D2, which is O(n), where n is taken to be the (larger) size of p and q.

Let’s now first formulate the approximation algorithm. The size of p and q is assumed to be the same without loss of generality since otherwise one can pad the short one to increase its length. Since edges starting from S and ending at D are all of cost 0, cf. Eq. (15), they can be saturated in the preprocessing step thus our procedure focuses on edges linking between p[1, n] and q[1, n]. Arrays s[1, n] and d[1, n] are employed to respectively keep track of supplies for pi’s and qj’s, which are changed dynamically as the procedure proceeds. In the algorithm, edge (i, j) is called saturated if one of the following three conditions is satisfied:

either fij = cij, the flow assigned reaches its designated capacity; or

s[i] = 0, no supplies are available at pi; or

d[j] = 0, no demands are requested by node qj any longer.

To saturate an un-saturate edge, one only has to add min{cij, s[i], d[j]} to fij.

Algorithm.

greedyApproxMEMD.

| (1) Initialization: | ||

| Set all fij = 0 where cij > 0; | ||

| Set s[i] = wpi, d [i] = wqi, i = 1, 2,…, n; | ||

| (2) Incremental saturation: | ||

| for μ = 0 to 2d with increment δ | ||

| Saturate all un-saturated edges (I, j) of cost μ along the ascending order of i: | ||

|

||

| (3) Saturate remaining edges: | ||

| saturate remaining edges associated with D1 and D2. | ||

| (4) Termination: | ||

| Return Σij fijd(i, j) as MEMD | ||

| END greedyApproxMEMD | ||

In this algorithm, we are proceeding by considering edges according to the ascending order of their costs, an edge of higher cost will not be taken into account unless all edges of lower costs were already evaluated, i.e. we are making greedy choice along our optimality searching process. This is an actual greedy algorithm,25 a well-established efficient algorithmic design that was widely applied in Huffman encoding, minimum-spanning-tree problem and task scheduling. Instead of relying on Dijkstra’s procedure to successively find the shortest path in the graph where the searching process could be complex in the presence of augmenting paths, edges added to allow for possible reversal of previous flows. We register the shortest path in each iteration by taking the shortest possible one currently available to us, it is thus an approximation of the SSP-based algorithm to evaluate MEMD. Our algorithm is thus referred to as greedyApproxMEMD (GAM).

In the incremental saturation step of algorithm greedyApproxMEMD, the paths collected for μ ∈ [0, d] are the greedy version employed by MEMD, the latter may make some readjustments in later iterations by using augmenting paths thus reducing the cost. Consequently the corresponding number of units transported, denoted by GAM[0,d] and MEMD[0,d], respectively, has the inequality below due to the optimality of SSP:

| (27) |

As an illustration, for two binary strings p = 0010110 and q = 1001001 with d = 3, then GAM[0,d] only consists of two units due to the flow from p3 → q4 and p6 → q7. Whereas the SSP employed by the evaluation of MEMD will have three units by p3 → q1 (with cost 2), p5 → q4 (with cost 1) and q6 → q7 (with cost 1), more units are transported with less costs in MEMD thus resulting in smaller overall cost, since the total units to be transported for both are the same. Indeed in the first two iterations of SSP, the shortest paths found are the same as the two in GAM[0,d], that is, p3 → q4 and p6 → q7. In the third and final iteration, the augmenting path p5 → q4 → p3 → q1 with cost 2 is discovered since the cost for the reversed flow q4 → p3 is −1, which essentially transports p5 to q4 and returns the unit from q4 to p3 that was done in the preceding iteration and then move it to q1. Summarizing these three flows, the overall cost is thus 4. If we carry out the greedy flow search only based on the links defined by the network of MEMD, d(p5, q1) > d, thus 2c is levied for these two nodes. Since c = d+δ, where δ is of magnitude less than half of the difference of any two different metric distancesf (in our experiments, δ = 0.1), the overall cost then is 8.2 (2 * 1 + 2 * 3.1), more than doubled the true MEMD.

Therefore, due to Inequality (27) the greedy search with μ ∈ [0, d] is a poor approximation of the MEMD with value significantly larger than MEMD. Denoting this simplistic approximation ofMEMD as apx, we will perform a Monte Carlo study presently together with GAM. To remedy this lack of approximation, in GAM flows for μ ∈ (d, 2d] are also employed in spite of the fact that there is no edges between pi and qj if d(pi, qj) > d in the definition of MEMD. The rationale for us to further saturate these non-existing edges is that, when the Markov neighborhood size d is not too small, say, d ≥ 2, given the dense connections present in-between pi and qj dictated by MEMD, the probability for at least one of them to be labeled in earlier iterations and thus reversed in the augmented graph by SSP was extremely high, a flow from pi to qj is thus possible by crossing the reversed links with high probability. Returning to our illustrating example, although d(p5, q1) > d = 3, GAM still dictates a flow from p5 to q1 with cost 4. The resultant total cost produced by GAM is 6 (2 * 1 + 4), which reduced the error of apx by half with the same O(n) time complexity, although still two units larger than the optimal MEMD distance (4). Cases when d(pi, qj) > 2d are not of interest to us since simply connecting them to D1 or D2 will have a cost 2c = 2d + 2δ, which is smaller than any subsequent possible distance due to our choice of δ, namely, less than half of the smallest possible metric distance. The iteration for μ hence ends at 2d.

The GAM distance between two signatures is no larger than its corresponding apx distance. Indeed apx is the first part of GAM where μ ∈ [0, d], after-wards all un-matched units in both p and q are penalized by the cost c = d + δ. Conversely, in GAM, instead of simply taking units from D1 to fill out un-satisfied demands in q or dumping unused units in p to D2, for pi and qj where d(pi, qj) ∈ (d, 2d], a saturation step is attempted. If min{wpi, wqj} > 0, then a cost d(pi, qj) ≤ 2d is applied, which is strictly less than 2c = 2(d + δ) the indiscriminate cost levied by apx. Therefore the following inequality holds true:

| (28) |

So both MEMD and GAM yield a distance measure between two signatures no larger than apx. Next let’s compare the relation between MEMD and GAM. We must admit that perfect agreement between the flows generated by GAM and those by MEMD cannot be attained due to the reasons given below:

Case 1: The units with cost no larger than d transported by MEMD are larger than those of the same property by GAM, i.e. Ineq. (27).

Case 2: The lengths of a path assigned by SSP differ from those designated by GAM.

-

Case 3: No augmenting paths exist for some pi and qj when d(pi, qj) ∈ (d, 2d].

Case 4: The bottle neck for the existing augmenting path is less than the units GAM assigned, namely, min{wpi, wqj}.

Case 1 holds as remarked for the performance of apx. In case 2, the length of a path connecting pi and qj in GAM when d(pi, qj) > d is larger than that assigned by MEMD since in an augmenting path some links are of negative cost. These two cases give rise to relatively larger GAM than MEMD. The chance for these two cases to present is significant.

Case 3 is not a highly probable event for d ≥ 2 as just discussed. Again due to the exceedingly dense connections present between pi and qj when d is not too small, more than one augmenting path exists, their combined capacities are likely to exceed min{wpi, wqj}, hence Case 4 occurs as well with small probability. In both cases, should they occur, the resulting GAM is of distance shorter than MEMD. For example case 1 GAM2(1000, 0001) = 3 < MEMD2(1000, 0001) = 4.2; for case 2 GAM2(4111, 1114) = 9 < MEMD2(4111, 1114) = 10.2. Unlike apx that is always no less than MEMD, GAM does have a positive probability, especially when d ≤ 2, to be of smaller value than MEMD, especially when both signature size n and neighborhood degree d are small, which will be evidenced shortly in our Monte Carlo study.

These two different trends may hedge against each other and we may end up with similar overall distance between two signatures. Given the larger probability of the first two cases and relatively smaller chance of the last two cases, the GAM distance is larger than MEMD with high probability.

3.2. Monte Carlo studies of GAM and apx

At the end of the preceding subsection, we laid out heuristic arguments that GAM may be a valuable approximation of MEMD. This line of arguments is statistical that cannot be justified mathematically in a deterministic manner.26 We thus resort to a massive Monte Carlo study27,28 to statistically justify our heuristic arguments.

To carry out our Monte Carlo study, we randomly, using rand() in C++ or rand in Matlab, draw two vector pairs p and q of dimension 256, and then use SSP to evaluate its MEMD distance MEMD(p, q). Next call GAM to evaluate its approximate distance, denoted by GAM(p, q). To pose as a comparison, the apx part of GAM, that is, μ ∈ [0, d], is also invoked and the corresponding similarity measure is denoted by apx(p, q). To measure the difference between MEMD and GAM/apx, the following two relative errors are employed:

| (29) |

| (30) |

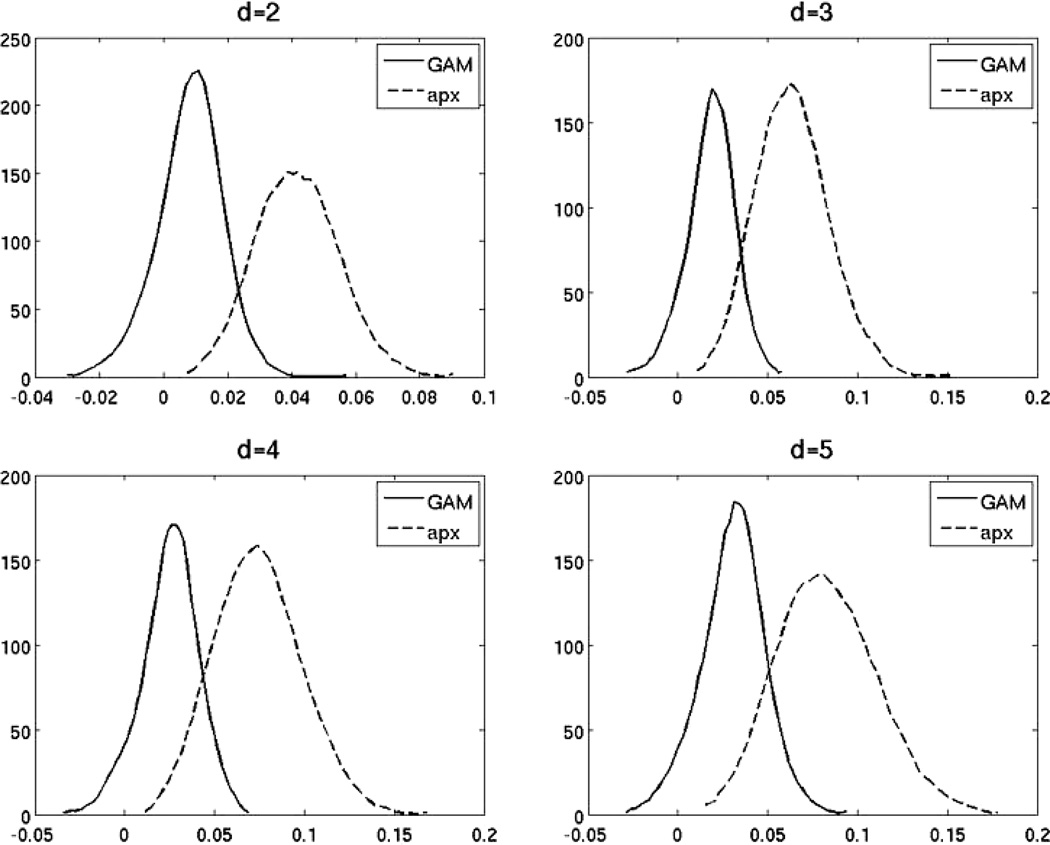

Our Monte Carlo study evaluates these two errors for the MEMD, GAM and apx for a large set of randomly drawn p and q to see if our heuristic arguments concerning the approximating power of GAM make sense. In Fig. 2, the εGAM and εapx for d = 2, 3, 4, and 5 for 5000 i.i.d. uniformly distributed random pairs are illustrated on the four panels. As can be clearly observed on all four panels, for all four thresholds εGAM is statistically significantly smaller than εapx, the addition of μ ∈ (d, 2d] enhances the approximating power considerably, which confirms our claim made in Ineq. (28). For d ≤ 4 the relative errors due to GAM is consistently less than 5%, indeed even for the worst case d = 4, the average relative error added by 1.64 standard deviations, the one-sided 95% confidence level, is still slightly less than 5%. In Fig. 2, a typical run of 5000 random pairs of vectors (individually) for all four cases is reported. We conduct this test for many more times with similar statistical results. Therefore, at least for relatively small d, we can safely claim that the difference between GAM(p, q) and MEMD(p, q) is statistically insignificant.

Fig. 2.

Statistical studies of the greedy approximation of MEMD for different neighborhood size d conducted over 5000 pairs of random vectors. Depicted are the histograms of the relative errors εapx as defined in Eq. (30) due to apx: the part of greedyApproxMEMD with μ ∈ [0, d] and εGAM as defined in Eq. (29) for GAM: the actual greedyApproxMEMD with μ ∈ [0, 2d] as given in Algorithm GAM.

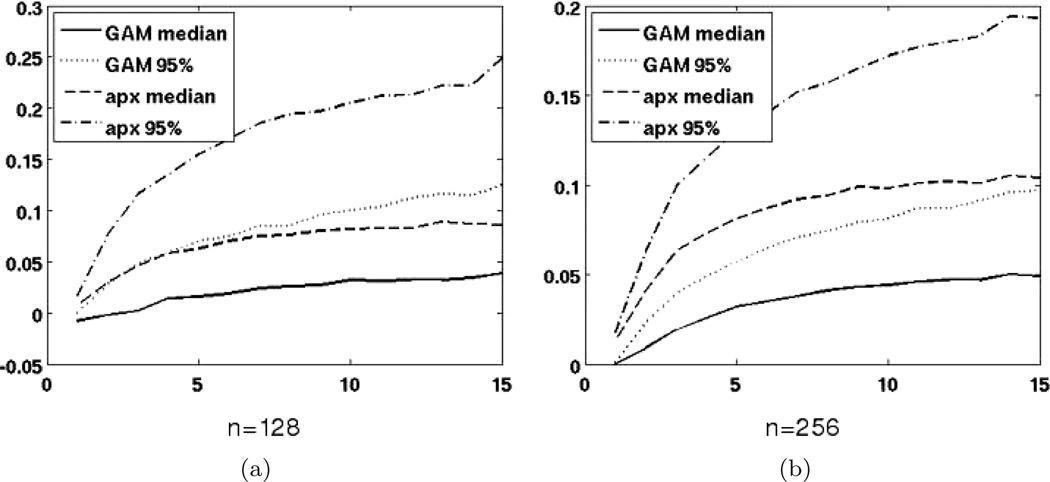

The statistical properties for different threshold d’s are demonstrated in Fig. 3(a) where the horizontal axis is the chosen threshold from 1 to 15, the vertical axis is the relative errors. The median relative error as well as the one-sided 95% confidence level are depicted for both GAM and apx. Where it can be observed that even for the worst case where d is of very large value 15, more than 95% of the relative errors for both cases are still below 0.1. The statistical properties for different vector sizes are similar to each other, the two cases n = 128 and n = 256 are illustrated on the two panels of this figure. For smaller threshold choices GAM is a fairly close approximation of MEMD.

Fig. 3.

Statistical properties for different vector sizes and threshold choices. (a) Relative errors (vertical axis) for size n = 128 with different thresholds (horizontal axis) from 1 to 15. (b) Relative errors for size n = 256 with different thresholds in [1, 15].

By contrast, for apx where μ ∈ [0, d] is employed, the resultant errors are significantly larger than GAM. Even for d = 2, the average relative error is already larger than 5%, it is thus a poor approximation of MEMD. It can only be a candidate for cases where d is very small, say less than 3.

With this Monte Carlo study we can have the following series of inequalities regarding the relationship among MEMD, GAM and apx:

| (31) |

where the first inequality ≼p indicates the fact that the GAM distance is no smaller than or approximates GAM distance by a high probability, while the second inequality is deterministic.

In our Monte Carlo studies, the metric system used is L1 since we are mostly concerned with vectors. In our formulation of MEMD any metric system can be plugged in to serve as d(;). We tested on L2 with similar statistical results.

In Markov chains29 and Markov Random Field,30 one rarely assigns too large a degree, usually d = O(1). Our probabilistic discussion as supported by Monte Carlo studies suggest that GAM is a reasonable approximation of MEMD with statistically insignificant relative errors. The processing time of GAM is all due to the Incremental saturation step, which is evidently (2d+1)n, since d = O(1), the time complexity of GAM is thereby O(n), a linear time algorithm. For instance, the time needed to evaluate the MEMD whose time complexity is O(n2 log n) between two 128-dimension vectors for d = 2 is 0.012 s on Pentium 2.20GHz, while for GAM it is only about 0.001 or less on the same machine. In cases where intensive computation is needed, GAM is a valuable approximation of MEMD given its close distance with significant reduction in time complexity. Interesting, although statistically a poor approximation of MEMD, apx is also a valuable approximation of MEMD in cases where d is of small magnitude, which is to be shown in our next empirical studies. Its time complexity is clearly O(n), smaller than GAM by a constant factor. Consequently apx is also tested as a viable alternative of the approximation of MEMD.

4. Experiments

In this section, experimental results using MEMD and its greedy approximations GAM and apx are presented for both synthetic and real world signatures. Comparisons with other related distances such as EMD, , EMD-L1, L1 and L2 are also given.

4.1. Synthetic examples

4.1.1. Deterministic synthetic examples

In our first set of synthetic studies, as tabulated in Table 1, several short and simple deterministic vectors are used to gain an initial understanding of the newly developed distance measure, namely MEMD, GAM and apx, as compared with other measures, EMD, , EMD-L1, L1 and L2.

Table 1.

Distances according to MEMD, GAM, apx as compared with EMD, , EMD-L1 for a deterministic set of synthetic vectors.

| p | q | MEMD2 | GAM2 | apx2 | EMD | EMD-L1 | L1 | L2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,1,1,1,0 | 0,1,1,1,1 | 4 | 4 | 4.2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1.4 |

| 2 | 5,5,5,5,0 | 0,5,5,5,5 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 1 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 7.1 |

| 3 | 1,0,0,0,0 | 0,0,0,0,1 | 4.2 | 4 | 4.2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1.4 |

| 4 | 5,0,0,0,0 | 0,0,0,0,5 | 21 | 20 | 21 | 4 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 7.1 |

| 5 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 1 | 2 | 255 | 2 | 1.4 | ||

| 6 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 1 | 10 | 1275 | 10 | 7.1 | ||

| 7 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 255 | 2 | 255 | 2 | 1.4 | ||

| 8 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 255 | 10 | 1275 | 10 | 7.1 | ||

| 9 | 5,0,0,0,0 | 0,0,0,0,0 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.5 | NAP | 10 | 20 | 5 | 5 |

| 10 | 5,0,5,0,5,0 | 0,5,0,5,0,5 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 15 | 15 | 30 | 12.2 |

| 11 | 5,5,5,0,0,0 | 0, 0,0,5,5,5 | 41 | 41 | 47 | 3 | 25 | 45 | 30 | 12.2 |

| 12 | 5,5,5,0,0,0 | 0,0,15,0,0,0 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 12.2 |

| 13 | 5,0,5,0,5,0 | 0,0,15,0,0,0 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 1.33 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 12.2 |

| 14 | 0, 0,1,1,1,1 | 0,1,1,1,0,0 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1.7 |

| 15 | 0, 0,1,1,1,10 | 0,1,1,1,0,0 | 24 | 24 | 25.2 | 1 | 22 | 3 | 12 | 10.1 |

In the first four rows of Table 1, the p and q in the 2nd and 4th rows are five times of those in the 1st and 3rd row, all but EMD give rise to distances five times larger. Due to the normalization step utilized in the definition of EMD, cf. Eq. (4), this desired proportional distance is not produced: EMD(11110, 01111) = EMD(55550, 05555) = 1, and EMD(10000, 00001) = EMD(50000, 00005) = 4. EMD’s closest variant EMD-L1 performs in a manner similar to others such as MEMD and in this group of vector pairs.

In the next group of four distances, Rows 5–8, for vectors of length 256, the global nature of EMD-L1 generates distance of very large magnitude that is not in agreement with common sensible definition of the corresponding pair of vectors. EMD-L1 thus fails to have a desirable distance measure for this group of data. In both groups L1 and L2 distances reflect their true distance nicely. In these distance evaluations, the differences among MEMD, GAM and apx are extremely small. also performs well.

Compare rows 5 and 9, as discussed in Sec. 1, the distance according to is problematic:

While it is preferable that vector 50000 should be closer to 00000 than 00005. EMD is not working in this case since there is no flow involved in this case and the normalization dictated by EMD gives rise to the division error. EMD-L1, like , fails to discriminate these two cases as well. The three distances in the MEMD group behave like L1 and L2 for these cases, which rightly assign larger distance between 50000 and 00005.

In row 10, 050505 is a local reversal of 505050. Whereas in Row 11, 000555 is a global reversal of 555000. In these two cases, the distances for the global reversal according to MEMD, GAM, apx, EMD and EMD-L1 are roughly three times of their corresponding distances for the local reversal. for the global reversal case is 25, less than twice of its value (15) in the local reversal case, which is not very desirable. Both L1 and L2 are not working for these cases at all: the distances for both reversals are the same. Indeed the simplistic L1 and L2 pay no heed to the local context and thus unable to tell the difference between these two cases, χ2-test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test have the same problem, this is the actual reason why EMD was developed and received great attention shortly in a wide range of research communities.7 In rows 12 and 13, the q’s are the same, 0, 0, 15, 0, 0, 0, where q3 is the sum of all elements of p’s, one is 555000, the other is 505050. Here again L1 and L2 entirely missed the difference between these two cases. All other distances correctly reflected the efforts to be made in transporting the earth from p to q.

In the last two rows, only MEMD, GAM, and approximately apx can handle the shift of the three 1 patterns with a varying values at the last position in p. EMD-L1 incorrectly comes up with the same distance for both cases.

In all 15 pairs of vectors, the MEMD and its two approximations GAM and apx align with the desired similarities fairly closely. While other distance measures made mistakes for some subset of cases.

4.1.2. Random synthetic examples

In a manner similar to editing actions in strings as we intensively researched in our work on Markov Edit Distance,31,32 where dynamic programming33 is used to evaluate similarities between two categorical patterns,34,35 in this section, we are about to study random errors that may often arise in numerical sequences such as adjacent data swapping, random data dropping or deletion, data insertion, data splitting or merging, global chunk swapping, global shift, and numerical sequences corrupted by Gaussian and salt/pepper noises. One sample pair for each of these eight cases with their distances according to MEMD, GAM, apx, EMD, , EMD-L1, L1 and L2 are shown in the eight rows in Table 2.

In row 1, to simulate the adjacent data swapping case, for a 10-d random vector (rand()%11) each position is swapped with its immediate neighbor with probability 0.7. Here except L1 and L2, all distances are of the similar value 12, which correctly reflected the number of units to be transported. Indeed by token of their dictated rule, all six distances in the EMD group can effectively handle this local swapping case.

Random data dropping/deletion is simulated in row 2, 0’s are padded to ensure the same size of both vectors. Here the 3 versions of our MEMD methods and are of similar distances around 50 to compensate for the three deleted values, namely, p3(8), p4(9) and p7(6). EMD-L1 produces a distance doubling this value for its global searching nature. The context-insensitive nature of both L1 and L2 makes their distances smaller than it should be.

To emulate random data insertions, with chance 0.3, a new random value (modula 10) is added after each element within vector p, one such realization is depicted in row 3. Similar to the prior data deletion case, the MEMD methods together with works fine for this case, while EMD-L1 and L1/L2 overly increases or reduces the due distance, respectively.

In the fourth row, a random splitting and merging are applied to a random vector, here like the swapping case the three MEMD methods, and EMD-L1 generate the same distance value given that they transported the same number of earth units.

In row 5, a global chunk swapping, which is usually employed in data management by Operating Systems, is effected by swapping the top five elements with the bottom ones in a 10-d random vector. The distances evaluated by MEMD, GAM, apx and EMD-L1 are similar. Whereas reduced the distances too much to merely 36, like a L1 distance (40) for this case, which failed to reflect the actual large global difference between these two vectors.

Row 6 simulates the global shift whereof the entire vector p is shifted to the left by three positions. Here the three MEMD approaches and yield similar distances at about 40. Conversely, EMD-L1 comes up with a very large value since it tries to globally find every possible match. Whereas L1 and L2 have relatively small value for its sheer ignorance of local contexts.

To simulate the Gaussian noise corruption cases, in row 7 a Gaussian noise process ~𝒩(0, 10) is added to a uniformly distributed 10-d vector that is uniformly distributed in [0, 100]. In theory the Markov nature of MEMD methods and should yield distances slightly larger than L1 since in the former distances local earth transportation is attempted. The MEMD and GAM reach the same distance 84.4 while apx yields a distance 94 since the latter only searches a subset of possible optimal paths. has a value (74) almost half-way in-between MEMD/GAM (84.4) and L1 (60). This is as expected since does not make an effort to tell the large distances between positions and the possible difference for the total mass of earth in the two signatures, cf. Eq. (5).

The last row simulates the random corruption by salt and pepper noise, here “salt” and “pepper” are 100, the largest possible value, and 0, the smaller possible value in p, respectively. In this case, the three MEMD methods and behave in like manner with significantly larger value than L1 given the considerably larger magnitude of the salt/pepper noise than Gaussian ones where the magnitudes are subdued at one-tenth of salt/pepper.

Table 2.

Distances according to MEMD, GAM, apx as compared with EMD, , EMD-L1, L1 and L2 for a set of random vectors pi and qi, i = 1, …, 6 that are shown in the second panel.

| p | q | MEMD2 | GAM2 | apx2 | EMD | EMD-L1 | L1 | L2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) swapping | p1 | q1 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 0.27 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 7.6 |

| (2) deletion | p2 | q2 | 52.3 | 52.3 | 52.3 | 0.09 | 50 | 98 | 31 | 11.8 |

| (3) insertion | p3 | q3 | 61.8 | 61.8 | 61.8 | 0.06 | 59 | 106 | 34 | 12.2 |

| (4) splitting/merging | p4 | q4 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 0.69 | 29 | 29 | 58 | 23.7 |

| (5) global change | p5 | q5 | 64 | 64 | 66.8 | 1.68 | 36 | 84 | 40 | 13.3 |

| (6) global shift | p6 | q6 | 40.7 | 40.7 | 40.7 | 0.15 | 39 | 118 | 25 | 10.1 |

| (7) Gaussian noise | p7 | q7 | 84.4 | 84.4 | 94 | 0.05 | 74 | 167 | 60 | 27.6 |

| (8) outliers | p8 | q8 | 247.2 | 247.2 | 252 | 0.02 | 232 | 709 | 120 | 70.1 |

| i | pi | qi |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6,8,6,10,6,2,0,3,3,0 | 8,6,6,6,10,2,3,3,0,0 |

| 2 | 8,4,8,10,9,7,6,6,3,4 | 0,8,4,10,7,6,3,4,0,0 |

| 3 | 5,8,3,8,3,8,1,6,4,0,0,0,0 | 5,8,3,10,9,8,3,8,1,6,4,4,5 |

| 4 | 8,2,9,2,2,6,1,4,3,5 | 0,19,0,0,10,0,0,8,0,5 |

| 5 | 5,9,7,7,5,7,5,3,1,1 | 7,5,3,1,1,5,9,7,7,5 |

| 6 | 3,5,7,2,4,7,5,5,9,3 | 0,0,0,3,5,7,2,4,7,5 |

| 7 | 16,97,96,49,80,14,42,92,79,96 | 14,104,90,71,79,15,53,93,78,88 |

| 8 | 73,49,58,24,46,100,55,52,0,49 | 73,100,100,24,46,96,55,52,23,49 |

Both Tables 1 and 2 are used to offer interesting illustrations concerning with the efficacy of the MEMD methods, they are anything but the proof of the discriminating power of this new distance measure, these examples are merely anecdotal evidence. To provide more statistically solid evidence, we first collect and compute its statistical properties of diid (p, q for two vectors p and q that are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), and then gather the same statistical properties for drel when p and q are related by actions that often arise in real numerical sequences, such as local swapping, data dropping, shift, etc. We then compute a ratio similar to t-score40 to quantify the discriminative power of the distance measure d(·, ·)

| (32) |

where μ and σ refer to the mean value and standard deviation, respectively. The larger rd is, which betokens the fact that the editing actions as flagged by rel is better singled out by the distance measure d(·, ·), the more discriminative power d(·, ·) encompasses.

To compare different distance measures d’s using rd, we conduct another Monte Carlo study. First 5000 pairs of 128-d iid vector (by calling rand()%100) p and q are randomly drawn and the corresponding μiid and σiid are evaluated. Next 5000 128-d iid vector p are randomly drawn, possible data corruptions or editing actions as detailed below:

Deletion: Any pi is dropped with probability 0.2 to yield qj’s.

Gaussian noise corruption: qi = pi + ε, where ε ~ 𝒩 (0, 10).

Global shifting: Shift the entire vector to the left or right by a random step (rand()%11-5).

Random insertion: Insert a new value rand()%100 with probability 0.2 at each position i.

Random outlier corruption: Replace a pi by salt(100) or pepper(0) with probability 0.2, i.e. pi = 100 rand()%2.

Random data splitting and merging: by probability 0.2, split one element (qi = pi * (rand()%10/10), and qi+1 = pi − qi, or merge two adjacent elements qi = pi + pi+1, qi+1 = 0.

Random data swapping: qi = pi+1 and qi+1 = pi with probability 0.2 for every i.

Moving average: , d is taken to be 2.

Median filtering: qi = med{pi−2, pi−1, pi, pi+1, pi+1}, for i = [3, n − 2].

The resultant vector is the actual q to be used to evaluate drel(p, q). We then evaluate the μrel and σrel, the corresponding rd’s for d to be MEMD, GAM, apx, EMD, , EMD-L1, L1 and L2 are tabulated in Table 3. As can be observed in this table, although not always the best distances for all cases, the three new distance measures perform consistently well in all cases. It is worth pointing out that although approximations of MEMD, apx and especially GAM, arrived at a performance exceedingly similar to MEMD for all cases. , within the same Markov framework, delivered valuable results as well — indeed it attains the best discriminative power in the deletion case while only failed one case, global shift with , which is not a miserable failure either, since the best ratio achieved by MEMD in this case is 0.95. L1 and L2, the simplest and presumably the worst distance measures, are not bad at all: in cases where the contextual dependence is not of crucial importance, such as splitting/merging, on-site Gaussian noise corruption and local median filtering, they beat other sophisticated distance measures, as such they are still competitive distance measures in the presence of so many mathematically sophisticated distance measures. For moving average, the popular smoothing operation for time series, they outperformed EMD, and EMD-L1, and are only slightly worse than MEMD and its two approximations. Furthermore, in the outlier case L2 has the best ratio since the negative impacts of the salt/pepper noises are suppressed by the square root operator. In these cases that are favorable to L1 and L2, the three MEMD methods trail not far behind, and interestingly, the apx, with more localized search, takes the leading role over GAM and MEMD. While lags far behind since it does not punish those faraway transportations as severely as done by the three MEMD methods. EMD and EMD-L1 are not working altogether in these cases given its global attempt to find matches. By contrast, if contextual dependence is involved, such as random data dropping or global data shifting, L1 and L2 offer little assistance.

Table 3.

rd’s as defined in Eq. (32) to according to MEMD, GAM, apx as compared with EMD, , EMD-L1, L1 and L2 for a set of random vector pairs.

| MEMD2 | GAM2 | apx2 | EMD | EMD-L1 | L1 | L2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) swapping | 3.46 | 3.37 | 3.36 | 1.22 | 2.63 | 1.61 | 1.80 | 1.15 |

| (2) deletion | 1.30 | 1.25 | 1.22 | 0.47 | 1.45 | 1.31 | 0.43 | 0.62 |

| (3) insertion | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.45 | 0.74 | 1.41 | 0.99 | 1.29 | 0.89 |

| (4) splitting/merging | 2.89 | 2.85 | 2.84 | 1.10 | 2.82 | 0.15 | 3.52 | 4.60 |

| (5) global shift | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| (6) Gaussian noise | 1.72 | 1.75 | 1.76 | 0.38 | 1.51 | 0.34 | 2.43 | 2.57 |

| (7) outliers | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.46 | 0.31 | 2.46 |

| (8) moving average | 2.71 | 2.76 | 2.81 | 1.23 | 1.76 | 0.59 | 1.86 | 2.08 |

| (9) median filtering | 1.34 | 1.42 | 1.43 | 0.55 | 0.83 | 0.08 | 1.72 | 1.50 |

4.2. Real world examples

To further explore the performances of different distance measures, in this section we apply these distance measures in content-based image retrieval (CBIR) applications.36,37 SIFT as developed by Lowe,13 one of the most influential image descriptors for CBIR purposes,38 is used as the content descriptors for images. Due to their rich visual effects, the Oxford image data setg that is used in Ref. 38 is employed. There are eight folders in this data set, each containing six images of the same scene going through various changes such as contrast and affine transformations. We use three images (Nos. 4–6) from each folder as the model images, one model image from each of the eight folders being shown in Fig. 4. The first three images from each folder serve as the foundation of our test images. To inspect the performance of different distance measures, each of the first three images from the eight folders go through various image processing, e.g. histogram equalization (histeq), filtering (imfilter), and noise corruption (imnoise), e.g. salt and pepper noise, provided by the image processing toolbox of Matlab. These are the actual images in our test folder upon which our performance results are based. The test images associated with “Bike 1” are depicted in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4.

Sample model images from the Oxford image datasets, one from each folder. Three images from each of the eight folders are used as the model images.

Fig. 5.

Sample test images for Bark 1 from the Oxford image datasets. Three images from the eight folders are chosen to be the test images, each test image spawns 10 test images after going through the image processing step such as filtering, noise corruption and rotation as provided by the image processing toolbox of Matlab.

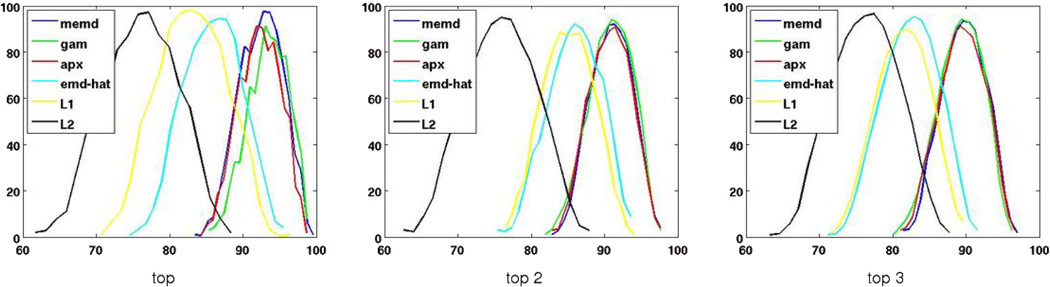

The SIFT descriptors for all images in the model and test folders are then computed by using Lowe’s original sift.m that is available at Lowe’s seminal SIFT Keypoint Detector website in UBC (www.cs.ubs.ca/~lowe/keypoints), which are the actual visual content-based representations for the model and test images. The distance d(t, mi) between each test image t and model image mi is then computed according to their corresponding SIFT descriptors. If the top match mt, that is, mt = argminmi d(t, mi), comes from the same original folder as test image t, it is counted as a correct match. The percentages of correct models present in the top 1, 2 and 3 matches for different distance measure d(·, ·) can effectively reflect its discriminative power. The computations involved in this experiment are exceedingly immense. We thus conduct a bootstrapping study as advanced by Efron28 in order to gain better statistical insights. Toward that end, we first evaluate the distances between 2000 pairs of test and model images randomly drawn from the test and model folders.h To perform the bootstrapping studies, we then randomly choose 100 test images with replacement from this distance pool and compute the percentages of correct models among the top 1, 2 and 3 matches. As dictated by bootstrapping policy28 this random choice with replacement is repeated 1000 times, the mean μ and standard deviation σ for each measure on each case is then evaluated. In Fig. 6, the histograms of the number of correct models in top 1, 2 and 3 matches for all eight measures are demonstrated. Table 4 tabulates the corresponding statistics for this bootstrapping study. The average running time for Oxford image set by all methods are reported in Table 5, where the theorectial time complexities are also given as a comparison.

Fig. 6.

Bootstrapping studies for different distance measures conducted on the Oxford image datasets. Legend: the horizontal axis is the percentage of correct model images that are present in the top one, two and three matches for the left, middle and right panels. The vertical axis is the counts (histogram) of a specific number of matches from the 1000 run of bootstrapping cases.

Table 4.

| MEMD2 | GAM2 | apx2 | L1 | L2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | μ | σ | |

| top match | 92.7 | 2.57 | 93.6 | 2.51 | 92.4 | 2.58 | 86.2 | 3.43 | 82.8 | 3.73 | 76.4 | 4.34 |

| top two matches | 91.1 | 2.54 | 91.0 | 2.68 | 90.9 | 2.65 | 86.2 | 3.13 | 85.0 | 3.16 | 76.0 | 4.17 |

| top three matches | 89.8 | 2.58 | 89.5 | 2.73 | 89.6 | 2.72 | 82.7 | 3.24 | 81.5 | 3.21 | 76.5 | 3.81 |

Table 5.

Average processing time used by all methods for the Oxford image dataset over a Pentium 2.20GHz CPU with 8GB RAM.

| MEMD2 | GAM2 | apx2 | EMD | EMD-L1 | L1 | L2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time complexity | O(n2 log n) | O(n) | O(n) | O(n3) | O(n2 log n) | O(n2) | O(n) | O(n) |

| mean time (seconds) | 809.87 | 1.17 | 0.94 | 5117.43 | 422.73 | 18.59 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

EMD and EMD-L1 are not reported in this CBIR study given their infeasibility in SIFT-based CBIR efforts, as already pointed out by Pele and Werman in Ref. 18 and confirmed by our experiments as well. However, to be fair with EMD and EMD-L1, this cannot be viewed as an entire failure at all since after all SIFT by itself is of local nature: it is a concatenation of a sequence of orientation histograms, the global search across all orientation histograms as done by EMD and EMD-L1 is hence infeasible.

It can be observed that although the time complexity of GAM and apx are reduced from MEMD’s O(n2 log n) to O(n), the recognition power of GAM and apx is not worse than MEMD: Indeed the performances attained by these three measure are so close that they are actually statistically indistinguishable as predicted by our statistical study conducted in the preceding section, c.f., Table 3, that is, the difference between the SIFT descriptors for different images is more predominant than that between MEMD and GAM/apx, especially when the Markov degree d is small (2) in our empirical studies. Just based on the numerical value tabulated in Table 4, MEMD is even worse than GAM and apx in two and one case, respectively.

5. Conclusion

Due to the small sample size and rampant noises, the goodness-of-fit methods such as χ2-test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test that are widely used in statistics are infeasible to measure the similarity/dissimilarity between signals and patterns due to the practical difficulty to perfectly align the two signals/patterns and take the context into account. A decade ago Rubner and colleagues7 formulated the EMD between two signatures as a transportation problem where earth or pebbles are transported from the source signature to the destination one. This flexibility of allowing across-bin movements entailed by EMD instantly finds a wide array of applications in many research communities. In spite of its great success, EMD suffers from several drawbacks such as global search of matches, normalization of flows and immense time complexity in a super-cubic order. To reduce its time complexity, EMD-L1 was developed to give rise to a O(n2) algorithm by taking advantage of the special L1 geometry.15 Even more exciting progress was made in by Pele and Werman14,18 where the global movements of earth are avoided by a transshipment procedure thus resulting in a more reasonable reflection of signatures at a significantly reduced time complexity O(n2 log n). In view of some short-comings of , we developed the MEMD within the transportation problem model by introducing the dumb source and destination nodes to handle the un-balanced supplies and demands whereof more reasonable distances are produced. The resultant MEMD is of time complexity O(n2 log n) that is still a computationally prohibitive procedure in the current era of multimedia world. We then developed two approximation procedures for MEMD, one is apx, the greedy search within the neighborhood system designated by MEMD. The other is GAM, the greedy approximation of MEMD, which searches matches in a neighborhood doubling the size dictated by MEMD. Intensive deterministic as well as Monte Carlo studies on synthetic and real world examples are conducted, MEMD and its approximations demonstrate promising performances in a consistent manner.

The GAM and apx is of a time complexity O(n) that is reasonably fast for most applications. However, when n is large, e.g. for digital library applications of great data volume,39 even a linear procedure is not a feasible solution. The inheritant local nature of MEMD and its approximations GAM and apx naturally entails the hierarchical computation. That is, one can represent vectors p and q in multiple resolutions such as Gaussian pyramid, Laplacian pyramid, wavelet transforms or k–d trees, the GAM or apx can be invoked hierarchically from the highest resolution all the way down to the lowest resolution, which can greatly reduce the time complexity needed to compute the distance for large n. When the degree d of the Markov neighborhood system needs to be large under certain circumstances, hierarchical evaluations can be carried out with smaller d′ in like manner that can cut the time complexity drastically.

Biography

Jie Wei received his B.Sc from University of Science and Technology of China, M.Sc from Institute of Software, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China, Ph.D from Simon Fraser University, Canada, in 1989, 1992 and 1999, respectively, all in computer science.

Since 1999 he has been on the faculty of Dept. of Computer Science, Grove School of Engineering, The City College of New York, where is now an associate professor. His research interests are image processing, computer vision and machine learning.

Footnotes

Based on M. Alipour’s EMD implementation (www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/12936), it takes 6.26 h on average over a Pentium 2.20GHz to compute the distance between the SIFT descriptors of two 256 × 256 gray-scale images. In this paper, all performance results for EMD are collected from this implementation.

The overhead involved in the set-up and maintenance of Fibonacci heap is not negligible, thus for small or medium size problems one may not want to use it algother.

Based on df2.m of package FastEMD-2 provided by Pele that is publicly available in www.cs.huji.ac.il/~ofirpele/FastEMD/code/. All performance results for in this paper are based on this original implementation.

Here the maximal distance allowed is set at 2. Indeed by putting the non-zero bin at any given max{dij} will result in the same arguments.

Ling and Okada’s EMD-L1 implementation is publicly available at www.ist.temple.edu/~hbling/code data.htm.

For L1, δ < 0.5; generally for Ln with degree d, .

The data set is publicly available at www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~vgg/research/affine.

These 2000 distances, mostly by MEMD and , already take the Pentium 2.20GHz CPU to run for more than three weeks continuously.

References

- 1.Stuart A, Ord K, Arnold S. Kendall’s Advanced Theory of Statistics: Classical Inference and the Linear Model. Vol. 2. London, NW1 3BH, UK: Hodder Arnold; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsen R, Marx M. An Introduction to Mathematical Statistics and Its Applications. 4th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ 07458: Prentice-Hall; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snedecor G, Cochran W. Statistical Methods. Ames, Iowa 50014: Blackwell Publishing; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peleg S, Werman M, Rom H. A unified approach to the change of resolution: Space and gray-level. IEEE Trans. PAMI. 1989;11(7):739–742. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mumford D. Mathematical theories of shape: Do they model perception? SPIE Vol. 1570 Geometric Methods in Computer Vision. 1991:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillier F, Lieberman G. Introduction to Mathematical Programming. New York, NY 10020: McGraw-Hill; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubner Y, Tomasi C, Guibas L. The earth mover’s distance as a metric for image retrieval. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2000;40(2):99–121. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen S, Guibas L. The earth mover’s distance under transformation sets. Proc. ICCV’99. 1999;2 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu D, Yan S, Luo J. Face recognition using spatially constrained earth mover’s distance. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2008;17(11):2256–2260. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2008.2004430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grauman K, Darrell T. Fast contour matching using approximate earth mover’s distance. Proc. CVPR’04. 2004;1:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indyk P, Thaper N. Fast image retrieval via embeddings. Proc. 3rd Int. Workshop on Statistical and Computational Theories of Vision. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lv Q, Charikar M, Li K. Image similarity search with compact data structures. ICIKM’04. 2004:8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe D. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant key-points. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004;60(2):91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pele O, Werman M. A linear time histogram metric for improved sift matching. ECCV. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ling H, Okada K. An efficient earth mover’s distance algorithm for robust histogram comparison. IEEE Trans. PAMI. 2007;29(5):840–853. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2007.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirdhondar S, Jacobs D. Approximate earth mover’s distance in linear time. Proc. CVPR’08. 2008:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li P, Wang Q, Zhang L. A novel earth mover’s distance methodology for image matching with gaussian mixture models. Proc. ICCV 2013. 2013:1689–1696. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pele O, Werman M. Fast and robust earth mover’s distances. ICCV. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillier FS, Lieberman GJ. Introduction to Operations Research. 7th edn. New York, NY 10020: McGraw-Hill; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahuja R, Magnanti T, Orlin J. Network Flows: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Upper Saddle River, NJ 07458: Prentice-Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinberg J, Tardos E. Algorithm Design. Boston, MA 02116: Addison-Wesley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griva I, Nash S, Sofer A. Linear and Nonlinear Optimization. Pheladelphia, PA 19104: SIAM; 2009. [Google Scholar]