Abstract

Conversion of one cell type into another cell type by forcibly expressing specific cocktails of transcription factors (TFs) has demonstrated that cell fates are not fixed and that cellular differentiation can be a two-way street with many intersections. These experiments also illustrated the sweeping potential of TFs to “read” genetically hardwired regulatory information even in cells where they are not normally expressed and to access and open up tightly packed chromatin to execute gene expression programs. Cellular reprogramming enables the modeling of diseases in a dish, to test the efficacy and toxicity of drugs in patient-derived cells and ultimately, could enable cell-based therapies to cure degenerative diseases. Yet, producing terminally differentiated cells that fully resemble their in vivo counterparts in sufficient quantities is still an unmet clinical need. While efforts are being made to reprogram cells nongenetically by using drug-like molecules, defined TF cocktails still dominate reprogramming protocols. Therefore, the optimization of TFs by protein engineering has emerged as a strategy to enhance reprogramming to produce functional, stable and safe cells for regenerative biomedicine. Engineering approaches focused on Oct4, MyoD, Sox17, Nanog and Mef2c and range from chimeric TFs with added transactivation domains, designer transcription activator-like effectors to activate endogenous TFs to reprogramming TFs with rationally engineered DNA recognition principles. Possibly, applying the complete toolkit of protein design to cellular reprogramming can help to remove the hurdles that, thus far, impeded the clinical use of cells derived from reprogramming technologies.

Keywords: cellular reprogramming, protein design, protein engineering, synthetic transcription factors, transactivation

SWITCHING CELL FATES WITH TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR PROTEINS

The notion that organismic development does not stubbornly follow a predetermined path but is a rather plastic process has been made long before DNA was recognized as the carrier of inheritable information.1 Nearly 100 years later, cellular reprogramming was first demonstrated when live tadpoles arose after transferring the nuclei of frog intestine derived somatic cells into oocytes.2 This observation led to the realization that even fully differentiated cells must still contain the complete genetic blueprint required to build a whole organism. That transcription factors (TFs) are remarkably powerful to drive cellular reprogramming, that is to convert one cell type into another, was first demonstrated by turning a mouse fibroblast into a muscle cell with a cDNA encoding a single TF, MyoD (Myod1).3 Subsequently, a cocktail of four TFs, Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4), c-Myc, Sry (sex determining region y) box2 (Sox2) and octamer binding protein 4 (Oct4), was discovered to induce pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) when forcibly expressed in fibroblasts of mouse4 and human.5,6 Since this seminal work, cellular reprogramming has become a mainstream research activity. Like embryonic stem cells derived from the blastocyst, iPSCs can be passaged in culture for indefinite periods and given appropriate growth conditions, can be differentiated into all cell types of the body.7 The latter can straightforwardly be demonstrated by transplanting iPSCs back into blastocysts, but it is a challenge to recapitulate this process in vitro.

The MyoD experiment already demonstrated that differentiated cells do not have to be pushed up all the way the “Waddington canal”8 to a completely undifferentiated cell type before subsequent re-specification to an alternative cell fate. Instead, the MyoD conversion of fibroblasts directly to muscle indicates that direct transdifferentiation can be accomplished without a pluripotent intermediate. Yet, analogous to the MyoD example, lineage conversion was initially only reported between cell types originating from a similar developmental trajectory such as the interconversion of two immune cell types, B cells (lymphoid cells) to macrophages (myeloid cells),9 exocrine to endocrine pancreatic cells,10 glial cells to neurons,11 brown fat to muscle cells12 and fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes.13 All of these transdifferentiation events are within the same germ layer (i.e. mesoderm to mesoderm or neurectoderm to neurectoderm). Eventually, conversions between cells originating from different germ layers could also be achieved as fibroblast as well as hepatocytes could be directly converted into functional neurons with defined TF cocktails.14,15,16 Apparently, even pronounced reprogramming barriers separating very distant cellular states can be crossed with small sets of lineage specifying TF proteins. The appreciation of this astonishing developmental plasticity sparked a plethora of studies attempting to re-direct cell fates. For example, blood cells,17 endothelial cells,18 hepatocytes,19,20,21 sertoli cells22 and thymic epithelial cells23 could be successfully generated with TF cocktails. Readers are referred to excellent reviews that discuss the progress of cellular reprogramming and lineage conversions in more detail.24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 Remarkably, particularly potent reprogramming factors such as Oct4 were found to be able to induce reprogramming alone in certain cell types and other cell types with small molecule supplementation.34,35,36 Moreover, a few studies have reported that TFs can be omitted altogether as induced pluripotent or neuronal cells could be produced solely with small molecules.37,38 However, efficiency of chemical reprogramming is considerably lower than TF based approaches and applications currently remain limited to mice. Hence, TF based cell lineage conversions continue to be the most effective and versatile approach. Therefore, we will focus our discussion on efforts to enhance TF based cell lineage conversions through protein engineering.

ROADBLOCKS ON THE WAY TO FUNCTIONAL CELLS

The excitement sparked by cellular reprogramming is catalyzed by its promise to lead to new clinical applications. One strategy is to conduct “in vitro clinical trials.”26,39 That is, cells obtained from patients through biopsies, blood or urine samples are differentiated into disease-relevant cell types. Next, preselected drugs or drug libraries can be assessed for their toxicity and potential to exert curative effects on those cells. It is hoped that this approach will accelerate personalized therapies, facilitate drug discovery and avoid the prescription of drugs that are toxic or ineffective to certain patient populations. Moreover, reprogramming technologies can be used to model human diseases in a dish. Here, the behavior of cells derived from patients is compared to cells from healthy donors. If disease-causing mutations are known, the mutation can be engineered using genome editing technologies and genetically matched isogenic cell lines can be studied. This way, diseases can be understood at an unprecedented depth, cellular pathways can be mapped, biomarkers can be discovered and therapeutic strategies can be developed. Lastly, the holy grail of stem cell research is to produce functional cells that can be transplanted back into patients to remedy degenerative diseases.40 Encouragingly, diseases could be cured through cell therapies in animal models. For example, gene-corrected iPSC derived hematopoietic progenitors transplanted back into humanized sickle cell anemia mouse models could cure the animals.41 This has led to the hope that diseases caused by deficiencies in well-defined cell types such as type 1 diabetes,42 Parkinson's disease43 and retinal degeneration44 are curable with cell-based therapies. Though, hematopoietic stem cells have been used in bone marrow transplants since the 1950's, cell therapies in humans still pose major challenges, and daunting roadblocks remain. Most importantly, safety has to be rigorously assessed before transplanting the reprogrammed cells. iPSCs resemble cancer cells in many ways and are teratogenic when injected into mice. This poses a significant risk as incomplete differentiation, and remnant pluripotent cells could potentially lead to cancerous growth.45,46 Collectively, avoiding insertional mutagenesis, oncogenic TFs and pluripotent reprogramming intermediates could solve this problem. Furthermore, it is often problematic to terminally differentiate cells so that they fully replicate the function of the cells matured in vivo. Cells have to be stable and need to be expandable so that they can be produced in sufficient quantities needed to support transplantation medicine. Ideally, reprogramming strategies should leave the genome unscathed, utilize cells that are genetically matched to the recipient with just the disease-causing loci corrected and produce an epigenetic state identical to the tissue embedded cell they are meant to replace. While optimized factor cocktails, novel culture conditions and small molecule compounds will likely further advance reprogrammed cells toward the clinic, we surmise that the engineering of the reprogramming TFs themselves provides a viable strategy to be further explored.

DESIGNING BETTER PROTEINS

Bioengineering proteins to either enhance their activity or to install completely novel functions has been successfully accomplished in numerous instances. Day-to-day laboratory operations utilize a range of artificially enhanced proteins. Those include DNA polymerases with thoroughly optimized fidelity,47,48,49 proteases with engineered activity and substrate specificity50 and fluorescent proteins with increased brightness.51,52 Likewise, protein therapeutics are often rationally improved. In particular coagulation factors to treat bleeding disorders were bioengineered in a variety of ways.53 For example, factor IX was engineered to have prolonged activity by fusing it to a Fc fragment54 and the coagulation factor VIIIa was rationally mutagenized for inactivation resistance and optimized secretion profiles.55,56 More ambitious goals include the engineering of whole pathways leading to the biotechnological synthesis of new products.57,58

What are the methods protein designers use to achieve their engineering goals? A rather simple way is to concatenate functional protein domains or even whole proteins. Examples include fusions of green fluorescent protein with antibody fragments that increase their brightness59 or attaching effector domains such as nucleases to artificial TFs with customized DNA sequence preferences.60 In addition, functional regions such as phosphorylation sites, protease cleavage sites, and signaling sequences can be rationally modified to install desired properties.55,56 Most commonly, rational and randomization strategies are combined to achieve the desired results. Using the knowledge of the protein's structure, sequence conservation and functional insights gained from site-directed mutagenesis experiments can lead to the selection of functionally important structural elements. Such elements could be individual or a small set of amino acids, secondary structure elements or subdomains. Frequently, design efforts target catalytic centers, substrate binding pockets or macromolecular contact interfaces. Those elements can then be modified taking biophysical parameters such as charge, size, and hydrophobicity, as well as functional data and sequence information of homologs into account. Yet, rationally predicting how a specific structural modification affects protein activity is a daunting task as our understanding about the structural basis for protein function remains limited. Therefore, protein designers often subject, structural elements earmarked for protein optimization to directed evolution.61 This strategy requires a carefully designed randomization strategy, which can include error-prone polymerase chain reaction,62 site-directed mutagenesis with randomized oligos63 and “chimeragenesis,” that is the recombination of protein fragment libraries.64 Libraries of modified proteins now undergo a screening and selection procedure to identify variants with improved functionality. Selection systems include binding assays such as phage display,65 ribosome display,66 enzymatic assays,67 tests for protein stability,68 genetic complementation combined with phenotypic read-outs69 and in vitro compartmentalization.70 Obviously, selection system design is critical as desired protein variants would escape detection if the screen cannot rigorously discriminate between enhanced and unwanted variants of the designed protein.61

Remarkably, efforts are being made to design proteins entirely from scratch using fragment libraries of nonnatural peptide sequences with minimal architectural constraints. Given the mindboggling number of theoretically possible protein sequences this seems like a herculean feat. Nevertheless, de novo design has led to the creation of some functional sequences.71,72 Thus far, examples for the engineering of TF proteins are still rather rare. Here we ask whether the toolkit of protein engineering could be employed to design reprogramming TFs to more effectively engineer cell lineage conversions and to bring progress to regenerative biomedicine.

ENGINEERING SYNTHETIC REPROGRAMMING FACTORS

Enhancing reprogramming efficiency with potent transactivation domains

The optimization of reprogramming strategies has been a priority for many laboratories as the original protocol was rather inefficient. Efficiency enhancements could be achieved by supplementing the media,73 altering the factor cocktails,74,75,76,77 changing the sequence of factor addition,78 adding small molecules35,79,80,81,82,83,84 or removing reprogramming roadblocks.85,86 In addition, some studies resorted to protein engineering to improve reprogramming (Table 1). Based on the assumption that reprogramming TFs mainly act by inducing mRNA synthesis of their target genes, several engineering efforts were made to increase the transactivation potential of TFs by fusing them to potent transactivation domains (TADs) (TAD-TFs, Figure 1).

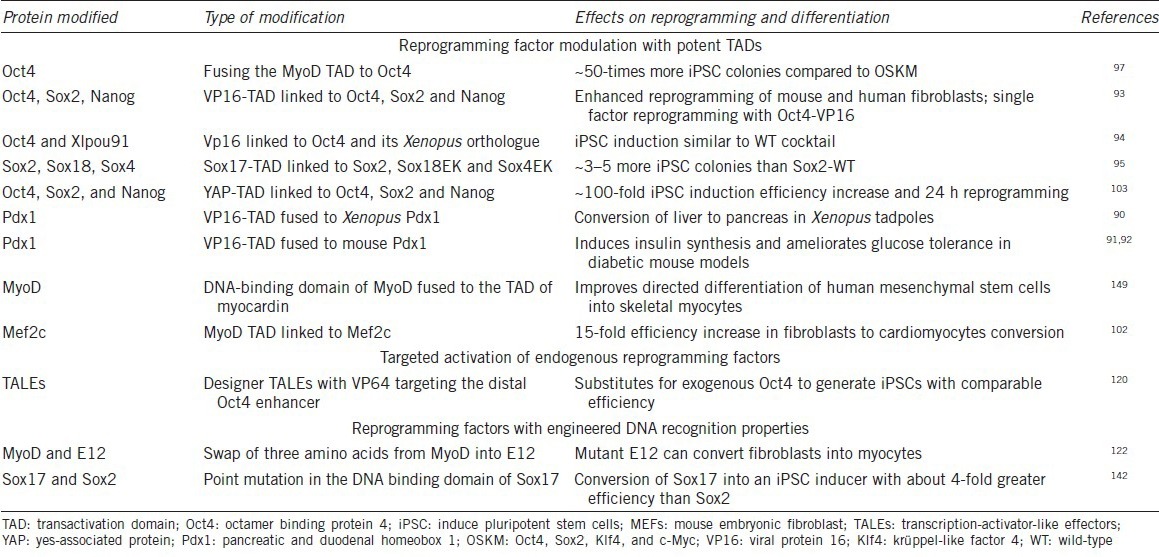

Table 1.

Engineered reprogramming factors

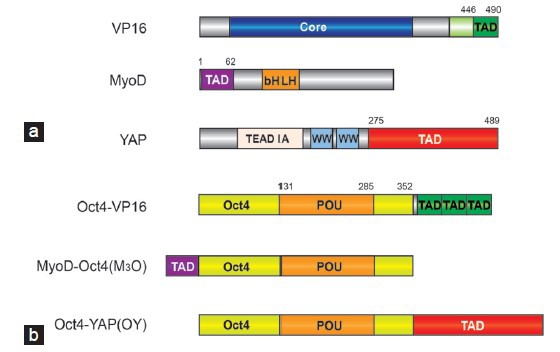

Figure 1.

Enhancing reprogramming efficiency with TAD-TF chimeras. (a) Domain structure of VP16, MyoD and YAP from which TADs were derived. (b) Domain structure of chimeric Oct4-TAD proteins demonstrated to potently enhance the reprogramming of somatic cells to iPSCs.93,97,103 YAP1 was drawn according to Uniprot-ID P46938 and VP16 and MyoD according to Hirai et al.,99 2010. TAD: transactivation domain; bHLH: basic helix-loop-helix domain; POU: Pit1-Oct-Unc-86 related domain; TEAD-IA: interaction region with the TF TEAD; TFs: transcription factors; Oct4: octamer binding protein 4; iPSCs: induce pluripotent stem cells; VP16: viral protein 16; YAP: yes-associated protein.

Viral protein 16-transactivation domain

The viral protein 16 (VP16) is a 490 amino acids TF protein of the herpes simplex virus with strong transactivating activity (Figure 1a). Its potent TAD was mapped and molecularly dissected more than 25 years ago and found to consist of an acidic C-terminal region spanning approximately 80 amino acids.87,88 Immediately after its discovery the VP16-TAD has been utilized to engineer chimeric TFs with enhanced activity.89 More recently, VP16 has also been utilized to enable cellular reprogramming. When the VP16-TAD was fused to the Xenopus ortholog of the pancreatic and duodenal homeobox1 (Pdx1), a chimeric protein could induce the conversion of liver cells to pancreatic cell in transgenic tadpoles.90 A similar Pdx1-VP16 fusion induced insulin biosynthesis and ameliorated glucose tolerance in mouse diabetic models.91,92 In an effort to enhance iPSC formation the VP16-TAD was fused to pluripotency reprogramming factors.93 In this study, a core fragment of the VP16-TAD (residues 446-490) was attached to Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and Nanog TFs separated by a glycine-rich linker (Figure 1a). With the exception of Klf4, the engineered TAD-TFs substantially outperformed the wild-type proteins with regards to both the efficiency and the kinetics of iPSC generation in mouse and human cells. Moreover, Oct4-VP16 alone could efficiently reprogram mouse embryonic fibroblasts into germline-competent iPSCs.93 An Oct4 construct containing three C-terminal VP16 copies arranged in tandem exhibited the highest efficiency (Figure 1b).

A separate study also reported that fusions of VP16 to mouse Oct4, human Oct4 and Xenopus Xlpou91 could support reprogramming as well as rescue Oct4 null ESCs.94 However, the authors did not observe a substantial enhancement in the reprogramming efficiency by the engineered proteins. The differences between the two studies could be caused by variations in the reprogramming conditions and construct design as different VP16 fragments, linkers, and VP16 copy numbers were used. The potency of the VP16-TAD for iPSC generation was again highlighted when it could be shown that fusions of VP16 to the truncated DNA binding high-mobility group (HMG) domain of Sox2 imparted some reprogramming activity to the otherwise inactive HMG fragments.95

MyoD-transactivation domain

Inspired by the remarkable potency of MyoD to single-handedly convert fibroblasts into muscle cells96 Hirai et al.97 asked whether the TAD of MyoD can enhance reprogramming to pluripotency. MyoD, a TF of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family,98 contains a ~60 amino acid TAD at its N-terminus99 (Figure 1a). The authors generated a series of MyoD TAD fragments and generated chimeric proteins by attaching them to the full-length mouse Oct4 protein. A chimeric protein consisting of a MyoD fragment (residues 1–62) attached to the N-terminus of Oct4 (termed M3O, Figure 1b) was found to strongly amplify the number of iPSC colonies in reprogramming assays using mouse and human cells. However, increasing the copy number of the M3 fragment was detrimental to iPSC generation. Notably, neither Klf4 nor Sox2 could be enhanced with the M3 fragment. Rather M3 Sox2 and M3 Klf4 fusions inhibited reprogramming. Likewise, replacing M3 with the TADs of Gata4, Mef2c, Tax and Tat eliminated the reprogramming activity of Oct4. Collectively, the engineered M3O factor appears to support reprogramming in a more specific and context-dependent manner in contrast to the VP16 fusions that allow a more flexible design.97 It was subsequently found that when culturing the cells in serum-free media at low density, M3O containing cocktails could enhance iPSC formation to 26% and 7% of the transfected mouse or human cells, respectively.100 Moreover, when tested side-by-side, the M3O construct outperformed Oct4-VP16 fusions.100 Consistently, in a study done by another group, M3O was found to accelerate reprogramming based on a cocktail using modified messenger RNAs.101 Motivated by the success in using the M3 domain to optimize Oct4 activity, Hirai et al.102 went on to ask whether factors involved in cardiac transdifferentiation can be improved through M3 chimeras. While M3 fusions to Gata4, Tbx5 and Hand2 had either no or adverse consequences, M3-Mef2c chimeras lead to a 15-fold increase in the number of beating clusters of induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs). Mef2c-VP16 fusions also showed some increase in iCM formation, albeit to only 20% of the M3Mef2c levels.

Yes-associated protein-transactivation domain

More recently, the TAD of the yes-associated protein (YAP) was used to engineer iPSC inducing TFs (Figure 1a).103 YAP is a downstream effector of the Hippo signaling pathway and co-activates transcription in concert with TFs of the TEAD family by recruiting histone methyltransferases.104 YAP promotes oncogenesis as well as the self-renewal of ESCs via its potent transactivation activity.105,106 Its C-terminal TAD was found to activate reporter genes as potently as the VP16 TAD.107 Zhu et al.103 fused the C-terminal YAP residues 275-489 to the C-termini of Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog to generate the engineered proteins Oy, Sy and Ny (Figure 1b). When this cocktail was used for iPSC induction in combination with native Klf4, the reprogramming efficiency rose from <1% to ~40%. Furthermore, the reprogramming kinetics was markedly accelerated with iPSC colonies appearing on the day after switching the transfected fibroblasts to ESC medium. The Sox2-YAP fusion was reported to be most critical for the acceleration among the three modified TFs.

What do the three TADs used to engineer reprogramming TFs have in common? They consist of predominantly acidic and hydrophobic residues leading to a strongly negative net charge. However, none of the TADs has been structurally characterized presumably due to their flexible structure in the absence of binding partners. Therefore, the molecular details of how those TADs create a chromatin environment instructive for the mRNA synthesis of nearby genes remains unclear. While a series of TAD interaction partners were previously detected,99,108 the affinity and selectivity of those TADs for co-regulators such as p300 or the mediator complex has not yet been studied in a systematic manner. Hence, whether those TADs mediate a general, or a TAD specific mechanism of transcriptional activation awaits further exploration. Collectively, there appear to be no obvious rules of how TAD-TF chimeras should be designed to engineer lineage converting TFs. Rather, optimal constructs had to be empirically produced for each TAD-TF combination.93,94,97 For example, increasing TAD copy numbers can either boost93 or impede TAD-TF activity.94,97,109 Further parameters to be optimized include the length of the TAD fragment used, the position of the TADs at either the N- or C-termini of the TFs, and the inclusion of linker sequences.

Inducing endogenous reprogramming factors with TAL effectors

Artificial proteins based on C2-H2 zinc-finger proteins (ZFPs), transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) and RNA-guided clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) Cas (CRISPR associated) can be designed to target genomic loci with high specificity. Typically, those proteins are constructed to contain nuclease effector domains that enable genome editing at single base-pair resolution (reviewed in110,111). While off-target effects had been a lurking concern, whole genome sequencing studies demonstrated that unwanted modifications are very rare.112,113 Recently, designer TALEs (dTALEs) and ZFPs have also been used to engineer transcriptional activators.114,115 TALEs consist 33-34 amino acid repeat domains with hypervariable residues at position 12 and 13.116 The identity of the dipeptide at positions 12/13 determines a recognition code (HD = C, NG = T, NI = A, NS = A, C, G or T, NN = A or G), which allows to rationally create dTALEs that recognize DNA sequences of choice.116 As up to 33 TALE repeat domains can be arranged in tandem, genomic loci can be targeted with high precision. Although, dTALE design is somewhat more straightforward than ZFP design, initial efforts were undertaken using ZFP-VP16 fusions constructed to target a sequence proximal to the transcriptional start site of Oct4.117 In another attempt, the fusion of a KRAB domain fused to a designer ZFP could activate endogenous Oct4 protein in series of cell lines.118 This was a surprising observation because the KRAB conventionally acts as transcriptional repressor. dTALE-VP16 fusions designed to bind proximal promoter sequences of SOX2, Klf4, c-MYC and Oct4 could activate reporter constructs, but only dTALEs targeting Klf4 and SOX2 could also activate the endogenous genes in 293FT cells.60 Moreover, dTALEs targeting the proximal promoter of Oct4 could activate the gene in NSCs where it is otherwise silenced. However, this strategy required the addition of histone deacetylase or DNA methyltransferase inhibitors suggesting that some chromatin loosening is needed for the dTALE-TF to access its target site.119

Gao et al.120 asked whether dTALE-TFs can replace conventionally used reprogramming TFs by activating their endogenous counterparts. The authors used VP64-TADs (four tandem repeats of VP16) to engineer designer transcription activators (A-dTF) that target distal enhancers of reprogramming factors.120 Indeed, a A-dTF designed to activate endogenous Oct4 could replace exogenous Oct4 and induce iPSCs in combination with c-Myc, Klf4 and Sox2. While reprogrammed cells appeared faster when using the A-dTF the overall iPSC colony yield was higher when Oct4 was used directly.120 The authors went on to show that A-dTF, targeting a distal Nanog enhancer could convert epiblast stem cells into ESCs. This study provides an elegant proof-of-concept that TALE-based TFs can replace native reprogramming factors. However, as the sole function of dTALE-TFs is to activate endogenous reprogramming factors that would eventually have to finish the job, it remains to be demonstrated whether this method can enhance cell lineage conversions.

Engineering chromatin association of reprogramming factors

Turning E12 into a myogenic transcription factor

The TAD-TFs and TFs endogenously activated by A-dTFs will likely engage the genome in the same manner as the native TFs as the DNA recognition domain is not modified. So far, only a few engineering efforts focused on protein interfaces involved in DNA recognition that would alter their genomic binding profile. Still, several swap experiments that install new functions and create engineered reprogramming TFs have been successful. The reprogramming pioneer Weintraub had provided the first evidence that lineage conversion activity of reprogramming TFs can be radically interchanged with strategically placed point mutations at the DNA contact interface.121,122 Following the seminal discovery that MyoD alone can induce a myogenic program in fibroblasts,3 Weintraub et al. continued to dissect the molecular basis of its specific activity. MyoD belongs to the bHLH family of TFs whose members bind to short palindromic CANNTG E-box motifs as homo-or heterodimers. By adopting a scissor-like architecture, bHLH TFs bind the major groove of the DNA through the basic regions of helix198 (Figure 2a). The E-box can be bound by most bHLH with similar affinity and many amino acids contacting the DNA are highly conserved. Nevertheless, some subtly different sequence preferences have recently been detected which could contribute to distinctive roles of bHLH TFs in cell fate determinations.123 Weintraub compared the DNA recognition and the reprogramming potential of MyoD and E12, another bHLH factor that is ubiquitously expressed and does not trigger myogenesis.121,122 By grafting just three amino acids from MyoD into E12: N114A and N115T of the basic region and D124K of the linker (MyoD numbering; residues 6,7 and 17 – numbering according to current bHLH conventions), E12 acquired the ability to convert fibroblasts into muscle cells121,122 (Figure 2a). As the Ala-Thr dipeptide is conserved in myogenic bHLH TFs, this sequence is critical for executing a myogenic gene expression program. Surprisingly, the large degree of sequence variation between MyoD and E12 outside the bHLH domain did not contribute to their cell type specific functions (Figure 2a). Rather, just three amino acids at the DNA interaction surface specify their functional diversity. Subsequent studies suggested that the Ala-Thr dipeptide affects the conformation of Arg-111 in the basic region and thereby modulates the access of Arg-111 to the major groove of the DNA binding site.124 Those rearrangements at the DNA-binding interface could translate into allosteric events at other interfaces, such as binding sites for chromatin modifiers, and thereby influence the functional consequences of the binding event.125

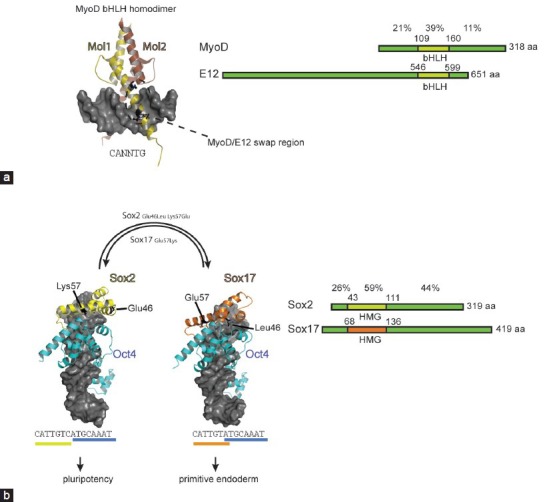

Figure 2.

Rational engineering how reprogramming factors read genomes. (a) Dimeric MyoD structure bound to DNA (pdb-ID 1 mdy98). The DNA is shown as a gray surface plot and the two MyoD molecules forming the dimer as yellow and brown cartoon. Residues engrafted from MyoD into E12 to turn E12 into a myogenic protein are shown as black ball-and-sticks and are highlighted with a dashed oval. (b) Structural models showing heterodimers of Oct4 (light blue) and Sox2 (yellow) on the canonical motif and Oct4-Sox17 (orange) on the compressed motif. Sox residues that determine the discriminative heterodimerization with Oct4 on canonical and compressed motifs are shown as black ball-and-sticks. Transplanting Lys57 from Sox2 into Sox17 alone turns Sox17 into a potent inducer of pluripotency.142 The structural models were constructed as described in146 based on coordinates derived from pdb-IDs 3f27 and 1 gt0.129,130,145 To the right of the structural cartoons the domain structure of MyoD versus E12 and Sox2 versus Sox17 is compared. The percentages above the domain plots indicate the amino acid identity between the protein pairs in the N-terminal, DNA binding and C-terminal region. The alignment was performed using sequences derived from Uniprot: MyoD P10085; E12:P15806; Sox2:P48432; Sox17:Q61473. Oct4: octamer binding protein 4.

Turning Sox17 into a pluripotency inducer

Our laboratory has made efforts to scrutinize the mechanism how proteins of the 20-member Sox family recognize their DNA target sites. Confusingly, all Sox proteins bind a near-identical CATTGT-like sequence126,127 and engage DNA by binding to the minor groove to induce a 70° kink using a conserved set of amino acids.128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136 How then can individual members select specific gene-sets to initiate characteristic cell fate decisions? The DNA binding HMG domain of Sox protein not only mediates sequence-specific DNA recognition but is also the main determinant of a partner code enabling selective interactions with other TFs.137,138,139,140,141 By conducting quantitative electrophoretic mobility shift assays to study the HMG mediated partnership with the Pit1-Oct-Unc-86 (POU) domain of Oct4, we observed different propensities of Sox-family members to heterodimerize with Oct4 on a series of differently configured composite sox-oct binding sites.133,142 In particular an unusual “compressed” element-where one nucleotide separating the sox and oct half sites is removed – still recruits Sox17/Oct4 dimers, whereas Sox2/Oct4 dimers can no longer assemble (Figure 2b). Conversely, the Sox2/Oct4 pair dimerizes markedly better on the canonical motif than the Sox17/Oct4 pair. In the search for the structural basis for these differences, a single amino-acid at position 57 of the HMG caught our attention. This residue, a Lys in Sox2 and a Glu in Sox17, shows a high degree of sequence variation amongst paralogous Sox proteins although it occupies a critical position at the Oct4 interaction interface.129,130,132,133 By exchanging this residue between Sox2 and Sox17 to produce Sox17EK and Sox2KE proteins, highly cooperative dimer formation of the Sox17EK/Oct4 complex on the canonical motif is installed. The wild type Sox2 normally partners with Oct4 in OKSM4,5 or OSNL (OS plus Nanog and Lin28)6 cocktails to activate the pluripotency circuitry. By contrast, the wild-type Sox17 induces endoderm differentiation when overexpressed in ESCs. The activity of the engineered factors was, therefore, studied in iPSC generation assays.142,143 When we replaced Sox2 with Sox17EK in OSKM cocktails, we could induce iPSCs with improved efficiency in both mouse142 and human cells.95 An analogously modified Sox7EK protein showed a similar behavior, whereas Sox4 and Sox18 needed additional TAD engineering for their conversion into reprogramming TFs.95 Using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing, we found that Sox17EK and Sox2 show a very similar binding profile when overexpressed in mouse ESCs.144 Both proteins pair with Oct4 on many genomic loci earmarked with canonical sox-oct motifs. By contrast, Sox17 partners with Oct4 on enhancers containing the compressed motif. Apparently, a single point mutation drastically changed how Sox proteins co-select their target genes by partnering with Oct4. Yet, the converse Sox2KE mutant could neither effectively dimerize with Oct4 on the canonical nor on the compressed sequence. This puzzle was resolved more recently when a novel Oct4 crystal structure and molecular dynamics simulation suggested an additional discriminatory interaction between residue 46 of Sox proteins with an Oct4 specific helix in the POU linker.145,146 Indeed, a rationally designed Sox2E46LK57E double mutant now cooperatively dimerizes with Oct4 on the compressed motif. It will be of interest to explore the activity of this engineered Sox factor in lineage conversion experiments.

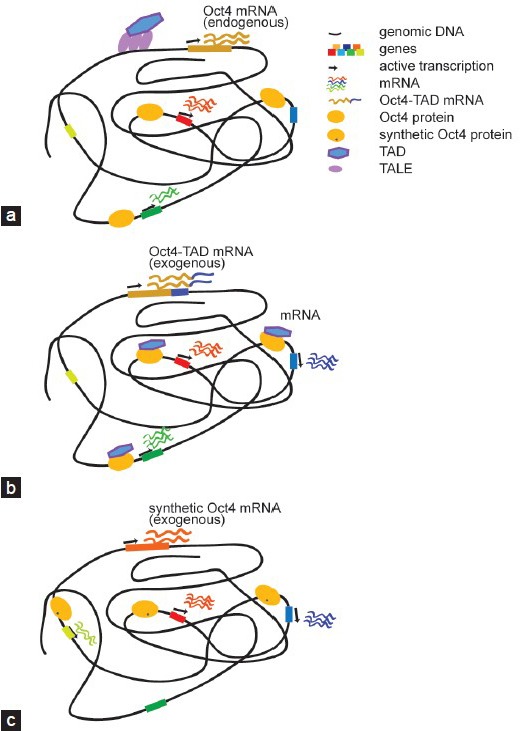

Collectively, the MyoD and Sox17EK examples show that the cell fate conversion potential of reprogramming TFs can be drastically changed with rather minimal modifications at structurally critical interfaces. We surmise that these insights could be utilized to engineer more potent and safer reprogramming TFs. Contrary to the TAD-TF and the TALE-TF approach; TFs with engineered DNA-binding domain likely engage the genome in a new manner (Figure 3). This way, it could be possible to break reprogramming barriers more effectively and to direct cells trapped in a local minimum of the Waddington landscape towards a desired state of differentiation.

Figure 3.

Regulatory outcome of different categories of engineered reprogramming TFs. (a) TALEs coupled with TADs can be engineered to switch on otherwise silenced reprogramming TFs. By targeting the distal enhancer of Oct4 its expression is activated. The resulting gene expression program is expected to resemble the wild-type scenario. (b) When potent TADs are fused to reprogramming TFs the chimeric protein is expected to target genomic regions reminiscent of the unmodified wild-type protein (a). However, the presence of a potent TAD elevates expression levels as compared to the wild-type and may also trigger the activation of genes that would otherwise be silent. (c) Rationally placed point mutations within the DNA binding domain can modify DNA recognition principles and alter the genomic binding profile. The cartoon represents a synthetic Oct4 with modified binding preferences that leads to the activation of genes that the wild-type protein would not switch on. TFs: transcription factors; TALEs: transcription activator-like effectors; TAD: transactivation domain; Oct4: octamer binding protein 4.

OUTLOOK — NOVEL APPROACHES FOR REPROGRAMMING FACTOR DESIGN

To produce cells for clinical applications, the process should be tightly controlled, fast and exclude undesired by-products. In particular, reprogramming to pluripotency has witnessed a multitude of studies aimed to improve the efficiency of iPSC generation (excellent reviews by Papp and Plath28 and Soufi31). Initially, iPSC generation was rather slow and only a small number of cells transfected with a cocktail of reprogramming TFs could be reprogrammed.4 Confusingly, it appeared that there is a high degree of randomness in cell populations and by simple chance a small subset of cells enters a path leading to the successive progression towards pluripotency in a more deterministic fashion.147,148 Yet, as roadblocks toward the pluripotency continue to be removed; fully controlled and efficient iPSC generation could soon be achieved.85,86 As the quality of iPSCs produced by engineered reprogramming factors was validated by examining their contribution to embryonic development and the capacity for germline transmission, synthetic TFs could still contribute to the ultimate cocktail.93,97,100,103,120 However, iPSCs are only an intermediary by-product on the way towards transplantation-grade functional cells. To lower the risk of cancerogenesis, a pluripotent intermediate should be avoided altogether or, minimally, complete differentiation of formerly pluripotent cells has to be ensured. Reproducibly generating functional cells to cure degenerative diseases will remain a challenge in the years to come. We anticipate that protein engineering techniques can help to overcome reprogramming barriers and better control cell lineage conversions to produce functional cells more safely and with properties more closely matching their in vivo counterparts (Figure 3). While widely used in fields such as enzymology and immunology, protein engineering is still in its infancy in cellular reprogramming. This is partly because of our incomplete understanding of how TFs work. Our structural knowledge is mostly restricted to isolated domains bound to short stretches of DNA. The mechanism of DNA target site selection, chromatin opening and how TFs stimulate mRNA synthesis remains largely unclear. Nevertheless, the studies highlighted in this review testify the promise of the approach and warrant further exploration as to whether protein engineering can bring stem cell biology closer to the bedside.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our laboratory is supported by the people's government of Guangzhou municipality Science and Technology Project 2011Y2-00026 and by a 2013 MOST China-EU Science and Technology Cooperation Program, Grant No. 2013DFE33080. V.M. thanks the CAS-TWAS President's Fellowship and UCAS for financial and infrastructure support. We thank Andrew Hutchins, Jiekai Chen, Ajaybabu Pobbati, Swaine Chen and Jörg Kahle for insightful comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haeckel EH. Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Siphonophoren. Utrecht: C. Van Der Post Jr. 1869 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurdon JB. The developmental capacity of nuclei taken from intestinal epithelium cells of feeding tadpoles. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1962;10:622–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis RL, Weintraub H, Lassar AB. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell. 1987;51:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai J, Zhang Y, Liu P, Chen S, Wu X, et al. Generation of tooth-like structures from integration-free human urine induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Regen (Lond) 2013;2:6. doi: 10.1186/2045-9769-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waddington CH. Organisers and Genes. The University Press; 1940 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie H, Ye M, Feng R, Graf T. Stepwise reprogramming of B cells into macrophages. Cell. 2004;117:663–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00419-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J, Melton DA. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells. Nature. 2008;455:627–32. doi: 10.1038/nature07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heins N, Malatesta P, Cecconi F, Nakafuku M, Tucker KL, et al. Glial cells generate neurons: the role of the transcription factor Pa×6. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:308–15. doi: 10.1038/nn828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008;454:961–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang ZP, Yang N, Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Fuentes DR, et al. Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature. 2011;476:220–3. doi: 10.1038/nature10202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP, Kokubu Y, Südhof TC, et al. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 2010;463:1035–41. doi: 10.1038/nature08797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marro S, Pang ZP, Yang N, Tsai MC, Qu K, et al. Direct lineage conversion of terminally differentiated hepatocytes to functional neurons. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:374–82. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo E, Rampalli S, Risueño RM, Schnerch A, Mitchell R, et al. Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to multilineage blood progenitors. Nature. 2010;468:521–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.1Margariti A, Winkler B, Karamariti E, Zampetaki A, Tsai TN, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into endothelial cells capable of angiogenesis and reendothelialization in tissue-engineered vessels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13793–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205526109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang P, He Z, Ji S, Sun H, Xiang D, et al. Induction of functional hepatocyte-like cells from mouse fibroblasts by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:386–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang P, Zhang L, Gao Y, He Z, Yao D, et al. Direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts to functional and expandable hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:370–84. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:390–3. doi: 10.1038/nature10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buganim Y, Itskovich E, Hu YC, Cheng AW, Ganz K, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into embryonic Sertoli-like cells by defined factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:373–86. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bredenkamp N, Ulyanchenko S, O’Neill KE, Manley NR, Vaidya HJ, et al. An organized and functional thymus generated from FOXN1-reprogrammed fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:902–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellin M, Marchetto MC, Gage FH, Mummery CL. Induced pluripotent stem cells: the new patient? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:713–26. doi: 10.1038/nrm3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graf T. Historical origins of transdifferentiation and reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:504–16. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grskovic M, Javaherian A, Strulovici B, Daley GQ. Induced pluripotent stem cells – opportunities for disease modelling and drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:915–29. doi: 10.1038/nrd3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanna JH, Saha K, Jaenisch R. Pluripotency and cellular reprogramming: facts, hypotheses, unresolved issues. Cell. 2010;143:508–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papp B, Plath K. Epigenetics of reprogramming to induced pluripotency. Cell. 2013;152:1324–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabour D, Schöler HR. Reprogramming and the mammalian germline: the Weismann barrier revisited. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:716–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sánchez Alvarado A, Yamanaka S. Rethinking differentiation: stem cells, regeneration, and plasticity. Cell. 2014;157:110–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soufi A. Mechanisms for enhancing cellular reprogramming. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2014;25:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induced pluripotent stem cells in medicine and biology. Development. 2013;140:2457–61. doi: 10.1242/dev.092551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vierbuchen T, Wernig M. Molecular roadblocks for cellular reprogramming. Mol Cell. 2012;47:827–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JB, Greber B, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, Meyer J, Park KI, et al. Direct reprogramming of human neural stem cells by OCT4. Nature. 2009;461:649–3. doi: 10.1038/nature08436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Cao N, Spencer CI, Nie B, Ma T, et al. Small molecules enable cardiac reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts with a single factor, Oct4. Cell Rep. 2014;6:951–60. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu G, Schöler HR. Role of Oct4 in the early embryo development. Cell Regen (Lond) 2014;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2045-9769-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng L, Hu W, Qiu B, Zhao J, Yu Y, et al. Generation of neural progenitor cells by chemical cocktails and hypoxia. Cell Res. 2014;24:665–79. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, Liu C, Guan J, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341:651–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heilker R, Traub S, Reinhardt P, Schöler HR, Sterneckert J. iPS cell derived neuronal cells for drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:510–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daley GQ. The promise and perils of stem cell therapeutics. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:740–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318:1920–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pagliuca FW, Melton DA. How to make a functional ß-cell. Development. 2013;140:2472–83. doi: 10.1242/dev.093187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buttery PC, Barker RA. Treating Parkinson's disease in the 21st century: can stem cell transplantation compete? J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:2802–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.23577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin ZB, Takahashi M. Generation of retinal cells from pluripotent stem cells. Prog Brain Res. 2012;201:171–81. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59544-7.00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohnishi K, Semi K, Yamamoto T, Shimizu M, Tanaka A, et al. Premature termination of reprogramming in vivo leads to cancer development through altered epigenetic regulation. Cell. 2014;156:663–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Patel PH, Kawate H, Adman E, Ashbach M, Loeb LA. A single highly mutable catalytic site amino acid is critical for DNA polymerase fidelity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5044–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Summerer D, Rudinger NZ, Detmer I, Marx A. Enhanced fidelity in mismatch extension by DNA polymerase through directed combinatorial enzyme design. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:4712–5. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leconte AM, Patel MP, Sass LE, McInerney P, Jarosz M, et al. Directed evolution of DNA polymerases for next-generation sequencing. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:5921–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yi L, Gebhard MC, Li Q, Taft JM, Georgiou G, et al. Engineering of TEV protease variants by yeast ER sequestration screening (YESS) of combinatorial libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:7229–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215994110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cormack BP, Valdivia RH, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–8. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heim R, Cubitt AB, Tsien RY. Improved green fluorescence. Nature. 1995;373:663–4. doi: 10.1038/373663b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fogarty PF. Biological rationale for new drugs in the bleeding disorders pipeline. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2011;2011:397–404. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2011.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peters RT, Low SC, Kamphaus GD, Dumont JA, Amari JV, et al. Prolonged activity of factor IX as a monomeric Fc fusion protein. Blood. 2010;115:2057–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swaroop M, Moussalli M, Pipe SW, Kaufman RJ. Mutagenesis of a potential immunoglobulin-binding protein-binding site enhances secretion of coagulation factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24121–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pipe SW, Kaufman RJ. Characterization of a genetically engineered inactivation-resistant coagulation factor VIIIa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11851–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schiel-Bengelsdorf B, Dürre P. Pathway engineering and synthetic biology using acetogens. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rohlin L, Oh MK, Liao JC. Microbial pathway engineering for industrial processes: evolution, combinatorial biosynthesis and rational design. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:330–5. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirchhofer A, Helma J, Schmidthals K, Frauer C, Cui S, et al. Modulation of protein properties in living cells using nanobodies. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:133–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang F, Cong L, Lodato S, Kosuri S, Church GM, et al. Efficient construction of sequence-specific TAL effectors for modulating mammalian transcription. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:149–53. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Romero PA, Arnold FH. Exploring protein fitness landscapes by directed evolution. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:866–76. doi: 10.1038/nrm2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cadwell RC, Joyce GF. Randomization of genes by PCR mutagenesis. PCR Methods Appl. 1992;2:28–33. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Irague R, Tarquis L, André I, Moulis C, Morel S, et al. Combinatorial engineering of dextransucrase specificity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hiraga K, Arnold FH. General method for sequence-independent site-directed chimeragenesis. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:287–96. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00590-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simon MD, Sato K, Weiss GA, Shokat KM. A phage display selection of engrailed homeodomain mutants and the importance of residue Q50. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:3623–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hanes J, Plückthun A. In vitro selection and evolution of functional proteins by using ribosome display. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4937–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo J, Gaj T, Barbas CF., 3rd Directed evolution of an enhanced and highly efficient FokI cleavage domain for zinc finger nucleases. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Asial I, Cheng YX, Engman H, Dollhopf M, Wu B, et al. Engineering protein thermostability using a generic activity-independent biophysical screen inside the cell. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2901. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suzuki M, Baskin D, Hood L, Loeb LA. Random mutagenesis of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I: concordance of immutable sites in vivo with the crystal structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9670–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tawfik DS, Griffiths AD. Man-made cell-like compartments for molecular evolution. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:652–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith BA, Hecht MH. Novel proteins: from fold to function. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:421–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fisher MA, McKinley KL, Bradley LH, Viola SR, Hecht MH. De novo designed proteins from a library of artificial sequences function in Escherichia coli and enable cell growth. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15364. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Esteban MA, Wang T, Qin B, Yang J, Qin D, et al. Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:71–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Feng B, Jiang J, Kraus P, Ng JH, Heng JC, et al. Reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with orphan nuclear receptor Esrrb. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:197–203. doi: 10.1038/ncb1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Han J, Yuan P, Yang H, Zhang J, Soh BS, et al. Tb×3 improves the germ-line competency of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;463:1096–100. doi: 10.1038/nature08735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heng JC, Feng B, Han J, Jiang J, Kraus P, et al. The nuclear receptor Nr5a2 can replace Oct4 in the reprogramming of murine somatic cells to pluripotent cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:167–74. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jiang J, Chan YS, Loh YH, Cai J, Tong GQ, et al. A core Klf circuitry regulates self-renewal of embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:353–60. doi: 10.1038/ncb1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu X, Sun H, Qi J, Wang L, He S, et al. Sequential introduction of reprogramming factors reveals a time-sensitive requirement for individual factors and a sequential EMT-MET mechanism for optimal reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:829–38. doi: 10.1038/ncb2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ichida JK, Blanchard J, Lam K, Son EY, Chung JE, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of tgf-Beta signaling replaces so×2 in reprogramming by inducing nanog. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li K, Zhu S, Russ HA, Xu S, Xu T, et al. Small molecules facilitate the reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts into pancreatic lineages. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:228–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nie B, Wang H, Laurent T, Ding S. Cellular reprogramming: a small molecule perspective. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:784–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shi Y, Desponts C, Do JT, Hahm HS, Schöler HR, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Oct4 and Klf4 with small-molecule compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:568–74. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhu S, Ambasudhan R, Sun W, Kim HJ, Talantova M, et al. Small molecules enable OCT4-mediated direct reprogramming into expandable human neural stem cells. Cell Res. 2014;24:126–9. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhu S, Li W, Zhou H, Wei W, Ambasudhan R, et al. Reprogramming of human primary somatic cells by OCT4 and chemical compounds. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:651–5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen J, Liu H, Liu J, Qi J, Wei B, et al. H3K9 methylation is a barrier during somatic cell reprogramming into iPSCs. Nat Genet. 2013;45:34–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rais Y, Zviran A, Geula S, Gafni O, Chomsky E, et al. Deterministic direct reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Nature. 2013;502:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Triezenberg SJ, Kingsbury RC, McKnight SL. Functional dissection of VP16, the trans-activator of herpes simplex virus immediate early gene expression. Genes Dev. 1988;2:718–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Triezenberg SJ, LaMarco KL, McKnight SL. Evidence of DNA: protein interactions that mediate HSV-1 immediate early gene activation by VP16. Genes Dev. 1988;2:730–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.6.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sadowski I, Ma J, Triezenberg S, Ptashne M. GAL4-VP16 is an unusually potent transcriptional activator. Nature. 1988;335:563–4. doi: 10.1038/335563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Horb ME, Shen CN, Tosh D, Slack JM. Experimental conversion of liver to pancreas. Curr Biol. 2003;13:105–15. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kaneto H, Nakatani Y, Miyatsuka T, Matsuoka TA, Matsuhisa M, et al. PDX-1/VP16 fusion protein, together with NeuroD or Ngn3, markedly induces insulin gene transcription and ameliorates glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 2005;54:1009–22. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nagaya M, Katsuta H, Kaneto H, Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC. Adult mouse intrahepatic biliary epithelial cells induced in vitro to become insulin-producing cells. J Endocrinol. 2009;201:37–47. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang Y, Chen J, Hu JL, Wei XX, Qin D, et al. Reprogramming of mouse and human somatic cells by high-performance engineered factors. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:373–8. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hammachi F, Morrison GM, Sharov AA, Livigni A, Narayan S, et al. Transcriptional activation by Oct4 is sufficient for the maintenance and induction of pluripotency. Cell Rep. 2012;1:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aksoy I, Jauch R, Eras V, Chng WB, Chen J, et al. Sox transcription factors require selective interactions with Oct4 and specific transactivation functions to mediate reprogramming. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2632–46. doi: 10.1002/stem.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Weintraub H. The MyoD family and myogenesis: redundancy, networks, and thresholds. Cell. 1993;75:1241–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hirai H, Tani T, Katoku-Kikyo N, Kellner S, Karian P, et al. Radical acceleration of nuclear reprogramming by chromatin remodeling with the transactivation domain of MyoD. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1349–61. doi: 10.1002/stem.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ma PC, Rould MA, Weintraub H, Pabo CO. Crystal structure of MyoD bHLH domain-DNA complex: perspectives on DNA recognition and implications for transcriptional activation. Cell. 1994;77:451–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hirai H, Tani T, Kikyo N. Structure and functions of powerful transactivators: VP16, MyoD and FoxA. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:1589–96. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103194hh. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hirai H, Katoku-Kikyo N, Karian P, Firpo M, Kikyo N. Efficient iPS cell production with the MyoD transactivation domain in serum-free culture. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Warren L, Ni Y, Wang J, Guo X. Feeder-free derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells with messenger RNA. Sci Rep. 2012;2:657. doi: 10.1038/srep00657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hirai H, Katoku-Kikyo N, Keirstead SA, Kikyo N. Accelerated direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocyte-like cells with the MyoD transactivation domain. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100:105–13. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhu G, Li Y, Zhu F, Wang T, Jin W, et al. Coordination of engineered factors with TET1/2 promotes early-stage epigenetic modification during somatic cell reprogramming. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2:253–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Qing Y, Yin F, Wang W, Zheng Y, Guo P, et al. The Hippo effector Yorkie activates transcription by interacting with a histone methyltransferase complex through Ncoa6. Elife. 2014:3. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lian I, Kim J, Okazawa H, Zhao J, Zhao B, et al. The role of YAP transcription coactivator in regulating stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1106–18. doi: 10.1101/gad.1903310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Overholtzer M, Zhang J, Smolen GA, Muir B, Li W, et al. Transforming properties of YAP, a candidate oncogene on the chromosome 11q22 amplicon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12405–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605579103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yagi R, Chen LF, Shigesada K, Murakami Y, Ito Y. A WW domain-containing yes-associated protein (YAP) is a novel transcriptional co-activator. EMBO J. 1999;18:2551–62. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.9.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hauri S, Wepf A, van Drogen A, Varjosalo M, Tapon N, et al. Interaction proteome of human Hippo signaling: modular control of the co-activator YAP1. Mol Syst Biol. 2013;9:713. doi: 10.1002/msb.201304750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Marcus GA, Horiuchi J, Silverman N, Guarente L. ADA5/SPT20 links the ADA and SPT genes, which are involved in yeast transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3197–205. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gaj T, Gersbach CA, Barbas CF., 3rd ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2013;31:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kim H, Kim JS. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:321–34. doi: 10.1038/nrg3686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Suzuki K, Yu C, Qu J, Li M, Yao X, et al. Targeted gene correction minimally impacts whole-genome mutational load in human-disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cell clones. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Veres A, Gosis BS, Ding Q, Collins R, Ragavendran A, et al. Low incidence of off-target mutations in individual CRISPR-Cas9 and TALEN targeted human stem cell clones detected by whole-genome sequencing. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Geissler R, Scholze H, Hahn S, Streubel J, Bonas U, et al. Transcriptional activators of human genes with programmable DNA-specificity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Morbitzer R, Römer P, Boch J, Lahaye T. Regulation of selected genome loci using de novo-engineered transcription activator-like effector (TALE)-type transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21617–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013133107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Boch J, Scholze H, Schornack S, Landgraf A, Hahn S, et al. Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-type III effectors. Science. 2009;326:1509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1178811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bartsevich VV, Miller JC, Case CC, Pabo CO. Engineered zinc finger proteins for controlling stem cell fate. Stem Cells. 2003;21:632–7. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-6-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Juárez-Moreno K, Erices R, Beltran AS, Stolzenburg S, Cuello-Fredes M, et al. Breaking through an epigenetic wall: re-activation of Oct4 by KRAB-containing designer zinc finger transcription factors. Epigenetics. 2013;8:164–76. doi: 10.4161/epi.23503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bultmann S, Morbitzer R, Schmidt CS, Thanisch K, Spada F, et al. Targeted transcriptional activation of silent oct4 pluripotency gene by combining designer TALEs and inhibition of epigenetic modifiers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5368–77. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gao X, Yang J, Tsang JC, Ooi J, Wu D, et al. Reprogramming to pluripotency using designer TALE transcription factors targeting enhancers. Stem Cell Reports. 2013;1:183–97. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Weintraub H, Dwarki VJ, Verma I, Davis R, Hollenberg S, et al. Muscle-specific transcriptional activation by MyoD. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1377–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Davis RL, Weintraub H. Acquisition of myogenic specificity by replacement of three amino acid residues from MyoD into E12. Science. 1992;256:1027–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1317057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.De Masi F, Grove CA, Vedenko A, Alibés A, Gisselbrecht SS, et al. Using a structural and logics systems approach to infer bHLH-DNA binding specificity determinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:4553–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Huang J, Weintraub H, Kedes L. Intramolecular regulation of MyoD activation domain conformation and function. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5478–84. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Meijsing SH, Pufall MA, So AY, Bates DL, Chen L, et al. DNA binding site sequence directs glucocorticoid receptor structure and activity. Science. 2009;324:407–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1164265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, van Norren K, Clevers H. Sox-4, an Sry-like HMG box protein, is a transcriptional activator in lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1993;12:3847–54. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Harley VR, Jackson DI, Hextall PJ, Hawkins JR, Berkovitz GD, et al. DNA binding activity of recombinant SRY from normal males and XY females. Science. 1992;255:453–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1734522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jauch R, Ng CK, Narasimhan K, Kolatkar PR. The crystal structure of the So×4 HMG domain-DNA complex suggests a mechanism for positional interdependence in DNA recognition. Biochem J. 2012;443:39–47. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Palasingam P, Jauch R, Ng CK, Kolatkar PR. The structure of So×17 bound to DNA reveals a conserved bending topology but selective protein interaction platforms. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:619–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Reményi A, Lins K, Nissen LJ, Reinbold R, Schöler HR, et al. Crystal structure of a POU/HMG/DNA ternary complex suggests differential assembly of Oct4 and So×2 on two enhancers. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2048–59. doi: 10.1101/gad.269303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Werner MH, Huth JR, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Molecular basis of human 46X, Y sex reversal revealed from the three-dimensional solution structure of the human SRY-DNA complex. Cell. 1995;81:705–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Williams DC, Jr, Cai M, Clore GM. Molecular basis for synergistic transcriptional activation by Oct1 and So×2 revealed from the solution structure of the 42-kDa Oct1.So×2.Hoxb1-DNA ternary transcription factor complex. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1449–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ng CK, Li NX, Chee S, Prabhakar S, Kolatkar PR, et al. Deciphering the Sox-Oct partner code by quantitative cooperativity measurements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4933–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Jauch R, Kolatkar PR. What makes a pluripotency reprogramming factor? Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:806–14. doi: 10.2174/1566524011313050011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.King CY, Weiss MA. The SRY high-mobility-group box recognizes DNA by partial intercalation in the minor groove: a topological mechanism of sequence specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11990–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Phillips NB, Racca J, Chen YS, Singh R, Jancso-Radek A, et al. Mammalian testis-determining factor SRY and the enigma of inherited human sex reversal: frustrated induced fit in a bent protein-DNA complex. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36787–807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kamachi Y, Kondoh H. Sox proteins: regulators of cell fate specification and differentiation. Development. 2013;140:4129–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.091793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kamachi Y, Uchikawa M, Kondoh H. Pairing SOX off: with partners in the regulation of embryonic development. Trends Genet. 2000;16:182–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sarkar A, Hochedlinger K. The sox family of transcription factors: versatile regulators of stem and progenitor cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wilson M, Koopman P. Matching SOX: partner proteins and co-factors of the SOX family of transcriptional regulators. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:441–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bernard P, Harley VR. Acquisition of SOX transcription factor specificity through protein-protein interaction, modulation of Wnt signalling and post-translational modification. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:400–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Jauch R, Aksoy I, Hutchins AP, Ng CK, Tian XF, et al. Conversion of So×17 into a pluripotency reprogramming factor by reengineering its association with Oct4 on DNA. Stem Cells. 2011;29:940–51. doi: 10.1002/stem.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Niakan KK, Ji H, Maehr R, Vokes SA, Rodolfa KT, et al. So×17 promotes differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells by directly regulating extraembryonic gene expression and indirectly antagonizing self-renewal. Genes Dev. 2010;24:312–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.1833510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Aksoy I, Jauch R, Chen J, Dyla M, Divakar U, et al. Oct4 switches partnering from So×2 to So×17 to reinterpret the enhancer code and specify endoderm. EMBO J. 2013;32:938–53. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Esch D, Vahokoski J, Groves MR, Pogenberg V, Cojocaru V, et al. A unique Oct4 interface is crucial for reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:295–301. doi: 10.1038/ncb2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Merino F, Ng CK, Veerapandian V, Schöler HR, Jauch R, et al. Structural basis for the SOX-dependent genomic redistribution of OCT4 in stem cell differentiation. Structure. 2014;22:1274–86. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Buganim Y, Faddah DA, Cheng AW, Itskovich E, Markoulaki S, et al. Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell. 2012;150:1209–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Buganim Y, Faddah DA, Jaenisch R. Mechanisms and models of somatic cell reprogramming. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:427–39. doi: 10.1038/nrg3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Gonçalves MA, Janssen JM, Nguyen QG, Athanasopoulos T, Hauschka SD, et al. Transcription factor rational design improves directed differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells into skeletal myocytes. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1331–41. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]