Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether the use of a GlideScope video laryngoscope (GVL) improves first-attempt intubation success compared with the Macintosh laryngoscope (MAC) in the emergency department (ED).

Design

A propensity score-matched analysis of data from a prospective multicentre ED airway registry—the Korean Emergency Airway Management Registry (KEAMR).

Setting

4 academic EDs located in a metropolitan city and a province in South Korea.

Participants

A total of 4041 adult patients without cardiac arrest who underwent emergency intubation from January 2007 to December 2010.

Outcome measures

The primary and secondary outcomes were successful first intubation attempt and intubation failure, respectively. To reduce the selection bias and potential confounding effects, we rigorously adjusted for the baseline differences between two groups using a propensity score matching.

Results

Of the 4041 eligible patients, a GVL was initially used in 540 patients (13.4%). Using 1:2 propensity score matching, 363 and 726 patients were assigned to the GVL and MAC groups, respectively. The adjusted relative risks (95% CIs) for the first-attempt success rates with a GVL compared with a MAC were 0.76 (0.56 to 1.04; p=0.084) and the respective intubation failure rates 1.03(0.99 to 1.07; p=0.157). Regarding the subgroups, the first-attempt success of the senior residents and attending physicians was lower with the GVL (0.47 (0.23 to 0.98), p=0.043). In the patients with slight intubation difficulty, the first-attempt success was lower (0.60 (0.41 to 0.88), p=0.008) and the intubation failure was higher with the GVL (1.07 (1.02 to 1.13), p=0.008).

Conclusions

In this propensity score-matched analysis of data from a prospective multicentre ED airway registry, the overall first-attempt intubation success and failure rates did not differ significantly between GVL and MAC in the ED setting. Further randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm our findings.

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was the largest propensity score-matched analysis of data from a prospective multicentre airway registry to compare the first-attempt intubation success rate between a GlideScope video laryngoscope and a Macintosh laryngoscope in an emergency department setting.

The investigators rigorously adjusted for baseline differences between the two groups using a propensity score matching process. This reduced selection bias and potential confounding effects, and increased the causal inference in this observational study.

Although a propensity score-matched analysis was used for coping with confounders, unknown confounders might not have been adequately adjusted, and hidden biases might have existed because of the influences of these unmeasured confounders.

Introduction

Tracheal intubation is an important resuscitative procedure in emergency departments (EDs), and direct laryngoscopy has been universally used for tracheal intubation in this setting. However, in some situations, visualising the glottis might be difficult or impossible during direct laryngoscopy. To overcome this limitation, various alternative airway devices including video laryngoscopes have been developed.

The GlideScope video laryngoscope (GVL) is the most commonly used video laryngoscope. Compared with direct laryngoscopy, GVL has been associated with improved glottic visualisation; however, intubation with the GVL has not demonstrated superiority to that with the conventional laryngoscope in intubation success.1–5 There are limited studies comparing GVL and conventional laryngoscopes in EDs, so the superiority of a GVL to a conventional laryngoscope in real ED practice could be questionable. Although several studies have compared these devices for tracheal intubation in the ED, most of these studies were observational and only one randomised controlled trial focused on patients with trauma.6–11 It is difficult to conduct a randomised controlled trial comparing these devices in EDs. Thus, to clarify the effectiveness of the GVL in real ED settings, further large observational studies with a propensity score-matched analysis and randomised controlled trials are required.

The aim of this was to evaluate whether the use of the GVL improves first-attempt intubation success compared with the Macintosh laryngoscope (MAC) in the ED. We hypothesised that tracheal intubation with the GVL would be associated with increased successful intubation on first attempt compared with the MAC.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was a retrospective analysis of data from a multicentre prospective airway registry. The registry was formed by a network of 13 academic EDs located in a metropolitan city and a province in an Asian country. Consecutive data from four academic EDs that had been equipped with identical GlideScopes (Verathon Medical, Bothell, Washington, USA), including a specialised rigid stylet (GlideRite), and MAC (German-type blade and fibre-optic light source) were included in this study. Each ED had an average of 30 000–60 000 patient-visits per year. The EDs employ full-time emergency physicians and direct 4-year emergency medical residency training programmes. Tracheal intubations are performed by emergency physicians (residents and attending physicians) or by the physicians (residents) in other specialties in the EDs. All the emergency physicians had participated in the airway management courses run by a local emergency airway management society as trainees or instructors. The courses consisted of lectures, small-group hands-on workshops including training for video laryngoscopes, and patient simulation with computerised mannequin simulators. The choice of devices for tracheal intubation was at the discretion of the intubator considering the patient's condition and clinical situations. However, all the EDs had the same policy that a senior physician must supervise each intubation conducted by a junior physician. The Institutional Review Board of each participating hospital approved this study.

Patients

Patients older than 18 years of age who underwent tracheal intubation at the four EDs during the 48-month period from January 2007 to December 2010 were enrolled in this study. We excluded cardiac arrest cases because the factors that would affect a successful first-attempt tracheal intubation were expected to differ from those in patients without cardiac arrest. We also excluded cases in which devices or approaches other than orotracheal were used for the first intubation attempt.

Data collection

We used a standardised data collection form that was developed during a consensus conference of the investigators. After performing a tracheal intubation, each intubator completed this form according to the registry guide, which included the categories, standard definitions of the variables, and abstraction instructions. The individual data were reviewed every day by a site investigator and entered into a web-based registry system (http://keams.or.kr/keamr). The site investigator compared the recorded data with the case report form of the individual patient and daily ED census to confirm that all data were consecutively collected. A data manager also monitored the comprehensiveness and integrity of the data during the study period, and the author HJC reviewed the original data at the end of the study.

The following variables were collected for this study: the patient-related factors—sex, age, estimated body weight, indications for intubation, and evaluated airway difficulty; the intubator-related factors—the clinical experience level and specialty of the intubator, the use of rapid sequence intubation, and failure to evaluate the intubation difficulty; the number of attempts; the intubation success or failure; and the adverse events. Additionally, we calculated the Intubation Difficulty Scale using the relevant variables recorded in the registry to reflect the actual difficulties experienced during the intubation process.12 A predicted difficult airway was defined as a case with multiple components from the modified LEMON mnemonic (look externally, evaluate mouth opening—thyromental distance—hyothyroidal distance, morbid obesity, obstruction, and neck mobility), an evaluation method for assessment of difficult orotracheal intubations.13 14

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a successful first attempt. An attempt was defined as a single insertion of the laryngoscope past the teeth. The secondary outcome was intubation failure, which was defined as one of the following situations: an oesophageal intubation, a change to a different device or intubator, or an inability to place the tube in more than three attempts.

Statistical analysis

A 10% difference between the groups was considered clinically significant, with a study power of 0.8 and a significance level of 0.05, and the calculations indicated that each group would require 320 patients, based on a previous study that reported 75% and 68% first-attempt intubation success rates with the GVL and the MAC, respectively.10 Given the possibility that patients might be excluded during the propensity score matching process, 500 patients were included in the GVL group.

To reduce the effect of the inherent selection bias in the comparison of the success and failure rates of the laryngoscopes as well as the potential confounding of an observational study, we performed a rigorous propensity score adjustment. The propensity scores were estimated without regard to the outcomes in a multiple logistic regression analysis. A total of 11 covariates were selected for the propensity score model as follows: the patient-related factors (sex, age, estimated body weight, patient type, and evaluated airway difficulty); the intubator-related factors (the clinical experience level of the first intubator, specialty of the first intubator, the use of rapid sequence intubation, and failure to evaluate the intubation difficulty); the Intubation Difficulty Scale rating; and the degree of intubation difficulty. Some patients could not be completely evaluated due to the intubation difficulty in the registry. Missing values (unrecorded data) in the difficult airway assessment section of the registry were regarded as absence of the difficulty predictor. Since these evaluation failures could reflect the urgency of the situation indirectly, we used it as a covariate for the propensity score model.

The model discrimination was assessed using c-statistics, and the calibration was assessed using Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics. Using the Greed 5:1 digit-matching algorithm, we created propensity score-matched pairs without replacements (a 1:2 match). To verify the covariate balancing after the propensity score matching, the standardised difference before and after the application of the propensity score matching was calculated. Additionally, the propensity scores were subdivided into quintiles. The effect was estimated separately within each quintile, and the quintile estimates were combined to yield an overall estimate of the effect. The statistics were presented as medians (ranges) for the continuous variables and frequencies (%) for the categorical variables. The comparison between the groups before the propensity score matching was conducted with the Wilcoxon rank-sum and χ2 tests. The comparison after the propensity score matching was conducted with the Wilcoxon signed-rank and McNemar’s tests. The adjusted risk ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs were calculated for the outcomes between the laryngoscopes. For exploratory analyses, we also performed a subgroup analysis with respect to the two major confounders (the level of the clinical experience of the intubator and the degree of intubation difficulty). The statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, V.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the patients

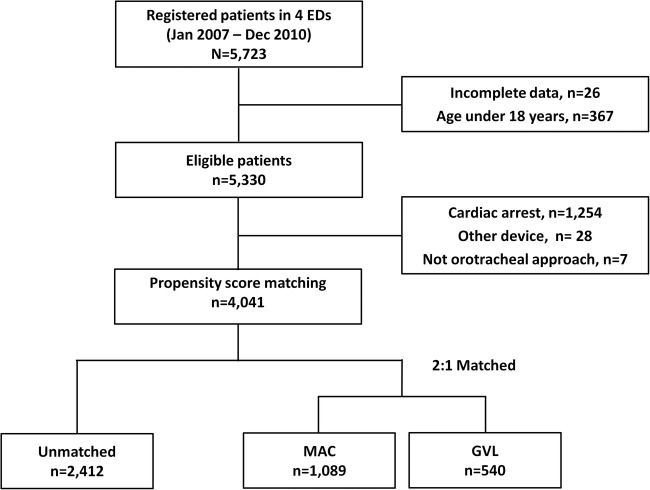

A total of 4041 eligible patients were enrolled in this study (figure 1). Of those, a GVL was used for the initial attempt in 540 patients (13.4%). An examination of the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the MAC and GVL groups revealed significant differences between the groups in all the variables except for sex, morbid obesity and the presence of an obstruction (table 1). When the groups were propensity score-matched according to the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, a total of 1089 patients were matched, and the MAC and GVL groups were found to be balanced for all the covariates.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for patient selection (ED, emergency department; GVL, GlideScope video laryngoscope; MAC, Macintosh laryngoscope).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of unmatched and propensity score-matched groups

| Unmatched group |

Propensity score-matched group |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVL (n=540) |

MAC (n=3501) |

p Value | GVL (n=363) |

MAC (n=726) |

p Value | |

| Age, year (range) | 59 (18–92) | 63 (18–107) | 0.001 | 62 (19–92) | 61 (18–106) | 0.321 |

| Male, n (%) | 337 (62.4) | 2124 (60.7) | 0.441 | 223 (61.4) | 452 (62.3) | 0.791 |

| Body weight, kg (range) | 65 (40–150) | 60 (30–177) | 0.001 | 65 (40–90) | 60 (30–100) | 0.215 |

| Patient type | <0.001 | 0.452 | ||||

| Medical, n (%) | 314 (58.2) | 2710 (77.4) | 251 (69.2) | 518 (71.4) | ||

| Trauma, n (%) | 226 (41.8) | 791 (22.6) | 112 (30.8) | 208 (28.6) | ||

| Difficult evaluation | ||||||

| Look, n (%) | 68 (12.6) | 97 (2.8) | <0.001 | 8 (2.2) | 12 (1.7) | 0.523 |

| Evaluate 3-3-2, n (%) | 90 (16.7) | 379 (10.8) | <0.001 | 35 (9.6) | 62 (8.5) | 0.547 |

| Morbid obesity, n (%) | 9 (1.8) | 38 (1.3) | 0.345 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.6) | 0.310 |

| Obstruction, n (%) | 14 (2.6) | 70 (2.0) | 0.369 | 9 (2.5) | 12 (1.7) | 0.350 |

| Neck mobility, n (%) | 111 (20.6) | 333 (9.5) | <0.001 | 39 (10.7) | 63 (8.7) | 0.270 |

| Use of RSI, n (%) | 271 (50.2) | 1172 (33.5) | <0.001 | 152 (41.9) | 315 (43.4) | 0.634 |

| Evaluation failure, n (%) | 50 (9.3) | 580 (16.6) | <0.001 | 43 (11.9) | 65 (9.0) | 0.132 |

| First intubators’ specialty | <0.001 | 0.892 | ||||

| EM, n (%) | 527 (97.6) | 2938 (83.9) | 354 (97.5) | 707 (97.4) | ||

| Others, n (%) | 13 (2.4) | 563 (16.1) | 9 (2.5) | 19 (2.6) | ||

| First intubators’ grade | <0.001 | 0.689 | ||||

| Junior (≤PGY 3), n (%) | 351 (65.0) | 2720 (77.7) | 269 (74.1) | 555 (76.5) | ||

| Senior (PGY 4, 5), n (%) | 124 (23.0) | 708 (20.2) | 90 (24.8) | 163 (22.4) | ||

| Attending, n (%) | 65 (12.0) | 73 (2.1) | 4 (1.1) | 8 (1.1) | ||

| Intubation Difficulty Scale | 1 (0–12) | 2 (0–14) | <0.001 | 1 (0–7) | 1 (0–14) | 0.215 |

| Degree of intubation difficulty | <0.001 | 0.106 | ||||

| Easy (IDS 0), n (%) | 232 (43.0) | 1171 (33.5) | 137 (37.7) | 306 (42.1) | ||

| Slight (IDS 1–5), n (%) | 288 (53.3) | 2070 (59.1) | 213 (58.7) | 381 (52.5) | ||

| Moderate-to-major (IDS>5), n (%) | 20 (3.7) | 260 (7.4) | 13 (3.6) | 39 (5.4) | ||

EM, emergency medicine; GVL, GlideScope video laryngoscope; IDS, Intubation Difficulty Scale; MAC, Macintosh laryngoscope; PGY, postgraduate year; RSI, rapid sequence intubation.

Main results

The overall first-attempt success rates were not significantly different, with 85.7% in the GVL group and 82.3% in the MAC group (p=0.051); and the intubation failure rates did not also differ between the groups (GVL vs MAC, 8.3% vs 10.0%; p=0.195) in the crude analysis. Using propensity score matching, 1089 patients were assigned to each group as follows: 726 in the MAC and 339 in the GVL groups. The RRs for the first-attempt success and failure rates in the GVL group vs the MAC group were 0.76 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.04) and 1.03 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.07), respectively (table 2).

Table 2.

First-attempt success and intubation failure rates in unmatched and propensity score-matched groups

| GVL | MAC | GVL vs MAC (reference) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | p Value | |||

| All patients (n=4041) | ||||

| First-attempt success rate, n (%) | 463 (85.7) | 2880 (82.3) | 1.24 (0.99 to 1.55) | 0.051 |

| Intubation failure rate, n (%) | 45 (8.3) | 350 (10.0) | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.195 |

| Propensity score-matched patients (n=1089) | ||||

| First-attempt success rate, n (%) | 307 (84.6) | 641 (88.3) | 0.76 (0.56 to 1.04) | 0.084 |

| Intubation failure rate, n (%) | 32 (8.8) | 46 (6.3) | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.07) | 0.157 |

GVL, GlideScope video laryngoscope; MAC, Macintosh laryngoscope; RR, risk ratio.

The crude analysis of the first-attempt success rates with both devices according to the experience levels of the first intubators revealed that within the junior resident group, the GVL success rate was 1.298-fold higher than the MAC success rate, a significant difference (p=0.047). However, within the senior resident and attending physician groups, there was no difference in the success rates of the devices. A propensity score-matching analysis revealed a significantly higher first-attempt success rate with the MAC than with the GVL (p=0.043) in the senior and attending groups. However, no similar significant difference was observed in the junior group. No group exhibited a significant difference in the intubation failure rate (table 3).

Table 3.

First-attempt success and intubation failure rates in unmatched and propensity score-matched groups by the first intubators’ grade

| First intubators’ grade | GVL | MAC | GVL vs MAC (reference) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | p Value | ||||

| All patients (n=4041) | |||||

| First-attempt success rate, n (%) | Junior (n=3071) | 297 (84.6) | 2177 (80.0) | 1.30 (1.00 to 1.68) | 0.047 |

| Senior/attending (n=970) | 166 (87.8) | 703 (90.0) | 0.82 (0.53 to 1.27) | 0.376 | |

| Intubation failure rate, n (%) | Junior (n=3071) | 33 (9.4) | 301 (11.1) | 0.98 (0.95 to 1.02) | 0.316 |

| Senior/attending (n=970) | 12 (6.4) | 49 (6.3) | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.04) | 0.970 | |

| Propensity score-matched patients (n=1089) | |||||

| First-attempt success rate, n (%) | Junior (n=824) | 227 (84.4) | 482 (86.9) | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.20) | 0.338 |

| Senior/attending (n=265) | 80 (85.1) | 159 (93.0) | 0.47 (0.23 to 0.98) | 0.043 | |

| Intubation failure rate, n (%) | Junior (n=824) | 26 (9.7) | 40 (7.2) | 1.03 (0.98 to 1.08) | 0.247 |

| Senior/attending (n=265) | 6 (6.4) | 7 (4.1) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.09) | 0.439 | |

GVL, GlideScope video laryngoscope; MAC, Macintosh laryngoscope; RR, risk ratio.

The crude analysis of the first-attempt success rates of the devices according to the degree of intubation difficulty, which was determined using the Intubation Difficulty Scale that reflected the difficulty of orotracheal intubation, found no difference between the groups. However, after propensity score-matching, higher first-attempt success rate and lower failure rate were achieved with the MAC relative to the GVL in slightly difficult cases (p=0.008 and 0.008, respectively). Moreover, in the moderate-to-extremely difficult cases, no first attempts were successful, and no significant difference was found between the intubation failure rates of the groups (table 4).

Table 4.

First-attempt success and intubation failure rates in unmatched and propensity score-matched groups by the degree of intubation difficulty

| Degree of intubation difficulty | GVL | MAC | GVL vs MAC (reference) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | p Value | ||||

| All patients (n=4041) | |||||

| First-attempt success rate, n (%) | Easy (n=1403) | 232 (100.0) | 1171 (100.0) | – | 0.999 |

| Slight (n=2358) | 231 (80.2) | 1709 (82.6) | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.13) | 0.323 | |

| Moderate to major (n=280) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | 0.999 | |

| Intubation failure rate, n (%) | Easy (n=1403) | 4 (1.7) | 24 (2.1) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) | 0.732 |

| Slight (n=2358) | 31 (10.8) | 189 (9.1) | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.06) | 0.401 | |

| Moderate to major (n=280) | 10 (50.0) | 137 (52.7) | 0.95 (0.60 to 1.49) | 0.812 | |

| Propensity score-matched patients (n=1089) | |||||

| First-attempt success rate, n (%) | Easy (n=443) | 137 (100.0) | 306 (100.0) | – | 0.999 |

| Slight (n=594) | 170 (79.8) | 335 (87.9) | 0.60 (0.41 to 0.88) | 0.008 | |

| Moderate to major (n=52) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | 0.999 | |

| Intubation failure rate, n (%) | Easy (n=443) | 2 (1.5) | 7 (2.3) | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.02) | 0.535 |

| Slight (n=594) | 24 (11.3) | 18 (4.7) | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.13) | 0.008 | |

| Moderate to major (n=52) | 6 (46.2) | 21 (53.9) | 0.86 (0.47 to 1.57) | 0.619 | |

GVL, GlideScope video laryngoscope; MAC, Macintosh laryngoscope; RR, risk ratio.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the largest propensity score-matched analysis of data from a multicentre prospective registry to compare the first-attempt success rates between two laryngoscopes (the GVL vs MAC) in the ED setting. Our study group has previously published a descriptive study about the use of GlideScope in EDs using the data from six hospitals from 2006 to 2008. In the study including 303 patients who underwent intubation with a GVL, the first-attempt success rate was 80.8%, which was higher than the 78.3% success rate with direct laryngoscopy, despite the lack of significance.7 Although we enrolled all patients consecutively, the study was observational and had the possibility of selection bias. Furthermore, the number of cases was not sufficient to run the propensity score-matched analysis. To overcome the limitations of the previous study, we gathered more data to perform the analysis. This attempt to increase the causal inference in an observational study could be viewed as a strength of this study.

In the crude analysis, the GVL tended to yield a higher first-attempt success rate compared with the MAC, but there was no statistically significant difference. After propensity score matching, no statistically significant difference was found in the first-attempt success rates between the two groups (84.6% of the first-attempt success rate with a GVL, 88.6% of that with a MAC). Additionally, the intubation failure rates were not also significantly different between the two groups. The results for primary outcome are similar to the results of a prospective observational study conducted by Platts-Mills et al8 of 280 patients in an ED (81% of the first-attempt success rate with a GVL, 84% for direct laryngoscopy) and a randomised controlled trial by Yeatts et al9 of patients with trauma in a trauma receiving unit (80% of the first-attempt success rate with a GVL and 81% for direct laryngoscopy).

On the other hand, our results are different from those of recent retrospective single-centre studies.10 11 Sakles et al10 reported that the first-attempt success rate with the GVL in 360 patients was 75%, which was better than the rate of 68% for direct laryngoscopy during the same period; this difference was greater in cases with two or more difficult airway predictors. A multivariate logistic regression analysis conducted by Mosier et al11 showed that the adjusted OR for GVL success was 2.20 (95% CI 1.51 to 3.19), indicating a significantly higher value. However, in our study, no difference was observed when the Intubation Difficulty Scale, which indicates the actual intubation difficulty, was used to compare the devices. In senior residents and the attending physician group, the MAC exhibited a better first-attempt success rate under identical conditions. However, in the junior residents group, no significant relationship was observed between the device type and the first-attempt success rate. The number of intubation experiences to achieve 90% predicted success with the MAC is at least 17, but the GVL requires less intubation encounters than the MAC.15 16 Thus, despite their relatively lesser experience with the GVL, the junior residents could show similar performance. On the other hand, since the senior residents and attending physicians have more experience with the MAC, they might exhibit a better performance in the first intubation attempt with the MAC than with the GVL. Given the added benefit of achieving better glottic visualisation, it is possible that the GVL might have been used preferentially over the MAC in difficult intubation cases. This possibility, however, was not measured as a predictive factor in this study.

Many researchers agree that the GVL provides better glottis visualisation than a conventional laryngoscope. However, numerous studies have reported difficulty in intubation with the GVL because of the steep blade curvature, despite the better view provided by this device.1 17 18 Also, the glottic view may be impaired by condensation of water vapour on the lens or obscured by mucus, blood or vomit, which is the primary cause of failure.10 Although a GVL might prove more advantageous for securing a view of the glottis, the conventional laryngoscope remains the primary tracheal intubation device in EDs; the video laryngoscope remains an alternative device because of the lack of support for its exclusive use.19 20 Video laryngoscopes with user-friendlier MAC-like blades have recently begun to exhibit better ED performances, and the role of video laryngoscopes in ED settings is expected to increase because of the educational advantages and potential telemedical uses.21–23 If intubators could have gained sufficient experience with respect to video laryngoscopes, as they did with direct laryngoscopes, the results of this study might have differed.

Our study has several limitations. First, intubators at multiple EDs registered the data. Although a standard data form and registration guide for site investigators were used, and also a site investigator at each hospital and a data manager monitoring the data completeness and quality, a self-reporting bias might inevitably be present in a registry-based study. Second, regardless of using a propensity score-matched analysis, our study results were not equivalent to those of a randomised controlled trial. Although a propensity score-matched analysis was used for coping with confounders, unknown confounders might not have been adequately adjusted, and hidden biases might have existed because of the influences of these unmeasured confounders. Thus, further multicentre randomised controlled trials are warranted to determine the efficacy of the GVL compared with the MAC in ED settings. Third, no time variables (time to glottic exposure or time to tube delivery) were included because of the logistical difficulty of the multicentre registry. Thus, exact reasons for intubation failure of the GVL could not be clearly identified. Fourth, although we used a popular mnemonic method, the prediction of difficult airways might have been subjective. In addition, the Intubation Difficulty Scale may perform less well with indirect laryngoscopes than the MAC and use of the Intubation Difficulty Scale or the degree of intubation difficulty as matching covariates may introduce a form of incorporation bias.24 Since the predicted difficult airway could not often reflect the actual difficulty during emergency intubation and unpredicted factors made the intubation difficult, we thought that the Intubation Difficulty Scale and degree of the intubation difficulty could reflect the actual difficulty during intubation. Therefore, additional studies with a more reliable difficult airway prediction method or a tool to reflect the actual difficulties during intubation in emergency situations are required. Finally, this study analysed intubations performed at four academic EDs in an Asian country during an early implementation period of the GVL and may therefore have limited generalisability because recently emergency physicians would be more familiar with the GVL.

Conclusion

In this propensity score-matched analysis of data from a prospective multicentre ED airway registry, the overall first-attempt intubation success and failure rates did not significantly differ between GVL and MAC in the ED setting. Further randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the Korean Emergency Airway Management Registry (KEAMR) investigators, the coordinators and the emergency medicine residents who worked in the EDs for their help with data input during the registry project.

Footnotes

Collaborators: The Korean Emergency Airway Management Registry (KEAMR) investigators.

Contributors: Y-MK and HJC conceived and designed the study. Y-MK, HJC, YMO and HGK collected and managed the data and performed the quality control. SHJ and HWY assisted with the study design and conducted the statistical analysis. Y-MK, HJC, YMO, HGK and HWY interpreted the results. HJC drafted the manuscript, and all the authors contributed substantially to its revision.

Funding: This study was supported in part by the internal research fund from Hanyang University (HY-2013-MC).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of each participating hospital approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sun DA, Warriner CB, Parsons DG et al. . The GlideScope video laryngoscope: randomized clinical trial in 200 patients. Br J Anaesth 2005;94:381–4. 10.1093/bja/aei041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nouruzi-Sedeh P, Schumann M, Groeben H. Laryngoscopy via Macintosh blade versus GlideScope: success rate and time for tracheal intubation in untrained medical personnel. Anesthesiology 2009;110:32–7. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318190b6a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griesdale DE, Liu D, McKinney J et al. . Glidescope® video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for tracheal intubation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anesth 2012;59:41–52. 10.1007/s12630-011-9620-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griesdale DE, Chau A, Isac G et al. . Video-laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy in critically ill patients: a pilot randomized trial. Can J Anesth 2012;59:1032–9. 10.1007/s12630-012-9775-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YK, Chen CC, Wang TL et al. . Comparison of video and direct laryngoscope for tracheal intubation in emergency settings: a meta-analysis. J Acute Med 2012;2:43–9. 10.1016/j.jacme.2012.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim HC, Goh SH. Utilization of a Glidescope videolaryngoscope for orotracheal intubations in different emergency airway management settings . Eur J Emerg Med 2009;16:68–73. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328303e1c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi HJ, Kang HG, Lim TH et al. . Tracheal intubation using a GlideScope video laryngoscope by emergency physicians: a multicentre analysis of 345 attempts in adult patients. Emerg Med J 2010;27:380–2. 10.1136/emj.2009.073460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platts-Mills TF, Campagne D, Chinnock B et al. . A comparison of GlideScope video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy intubation in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:866–71. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00492.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeatts DJ, Dutton RP, Hu PF et al. . Effect of video laryngoscopy on trauma patient survival: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;75:212–19. 10.1097/TA.0b013e318293103d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakles JC, Mosier JM, Chiu S et al. . Tracheal intubation in the emergency department: a comparison of GlideScope(R) video laryngoscopy to direct laryngoscopy in 822 intubations. J Emerg Med 2012;42:400–5. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosier JM, Stolz U, Chiu S et al. . Difficult airway management in the emergency department: GlideScope videolaryngoscopy compared with direct laryngoscopy. J Emerg Med 2012;42:629–34. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adnet F, Borron SW, Racine SX et al. . The Intubation Difficulty Scale (IDS): proposal and evaluation of a new score characterizing the complexity of tracheal intubation. Anesthesiology 1997;87:1290–7. 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aziz MF, Healy D, Kheterpal S et al. . Routine clinical practice effectiveness of the Glidescope in difficult airway management: an analysis of 2,004 Glidescope intubations, complications, and failures from two institutions. Anesthesiology 2011;114:34–41. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182023eb7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed AP. The unanticipated difficult intubation with adequate mask ventilation. Mount Sinai J Med 1995;62:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarasi PG, Mangione MP, Wang HE. Endotracheal intubation skill acquisition by medical students. Med Educ Online 2011;16:7309 10.3402/meo.v16i0.7309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savoldelli GL, Schiffer E, Abegg C et al. . Learning curves of the Glidescope, the McGrath and the Airtraq laryngoscopes: a manikin study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2009;26:554–8. 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283269ff4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupanovic M, Diachun CA, Isaacson SA et al. . Intubation with the GlideScope videolaryngoscope using the “gear stick technique”. Can J Anesth 2006;53:213–14. 10.1007/BF03021834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones PM, Turkstra TP, Armstrong KP et al. . Effect of stylet angulation and tracheal tube camber on time to intubation with the GlideScope. Can J Anesth 2007;54:21–7. 10.1007/BF03021895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilcox SR, Brown DF, Elmer J. Video laryngoscopy is a valuable adjunct in emergency airway management but is not sufficient as an exclusive method of training residents. Ann Emerg Med 2013;61:252–3. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.07.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothfield KP, Russo SG. Videolaryngoscopy: should it replace direct laryngoscopy? A pro-con debate. J Clin Anesth 2012;24:593–7. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakles JC, Mosier J, Chiu S et al. . A comparison of the C-MAC video laryngoscope to the Macintosh direct laryngoscope for intubation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:739–48. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakles JC, Patanwala AE, Mosier JM et al. . Comparison of video laryngoscopy to direct laryngoscopy for intubation of patients with difficult airway characteristics in the emergency department. Intern Emerg Med 2014;9:93–8. 10.1007/s11739-013-0995-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenland KB, Brown AF. Evolving role of video laryngoscopy for airway management in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas 2011;23:521–4. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01487.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McElwain J, Simpkin A, Newell J et al. . Determination of the utility of the Intubation Difficulty Scale for use with indirect laryngoscopes. Anaesthesia 2011;66:1127–33. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06891.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]