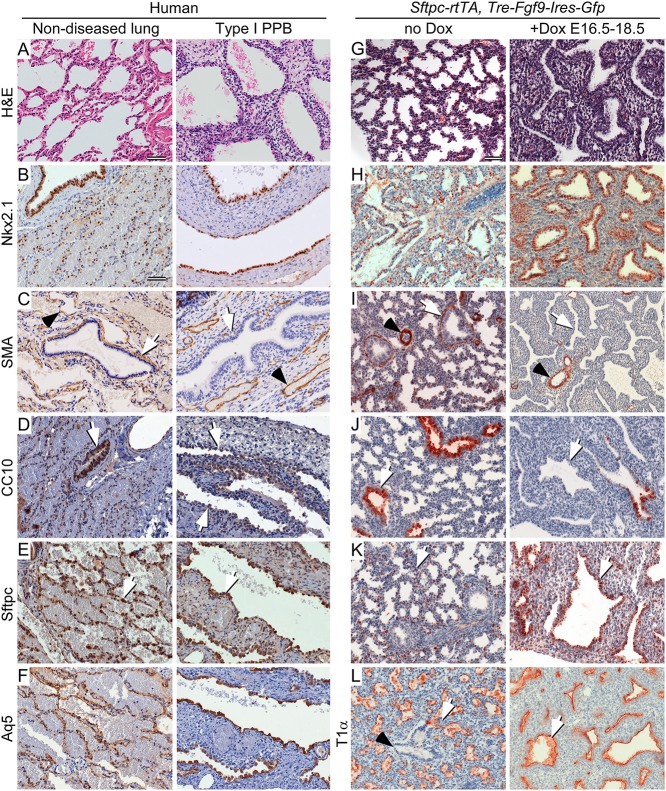

Fig 6. Type I PPB and induced late gestation expression of epithelial FGF9 in mice have similar histopathology and cell differentiation.

(A-F) Comparison of non-diseased human lung (left) and Type I PPB (right). (G-L) Comparison of normal (no Dox) E18.5 mouse lung (left) and mouse lung from Sftpc-rtTA, Tre-Fgf9-Ires-eGfp double transgenic mice induced (+Dox) to overexpress Fgf9 from E16.5 to E18.5 (right). (A and G) H&E stained histological sections. (B and H) Immunostaining for Nkx2.1 to identify lung epithelium. (C and I) Immunostaining for smooth muscle actin (SMA). Peri-bronchiolar SMA immunostaining (white arrow) and perivascular SMA immunoreactivity (black arrowhead) are differentially affected. (D and J) Immunostaining for Club cell secretory protein (CC10) showing reduced expression of CC10 in proximal lung epithelium (white arrow) compared to that of non-diseased human lung and uninduced mouse lung, respectively. (E and K) Immunostaining for surfactant protein C (Sftpc) showing expanded proximal expression (white arrow) in all cystic lung epithelium in human Type I PPB and Fgf9-induced mouse lung. In non-diseased human lung and uninduced mouse lung, Sftpc immunostaining (white arrow) was consistent with expression in Type II pneumocytes. (F and L) Immunostaining for the distal lung Type I pneumocyte marker Aquaporin 5 (Aq5, human) and T1α (mouse). In human, Aq5 was expressed in distal alveoli of non-diseased lung tissue and in Type I PPB associated epithelium. T1α was similarly expressed in distal mouse lung and throughout the epithelium of Fgf9-induced mouse lung (white arrow). (A) Three month-old female. (B-F) Three month-old female. Scale bar: A, 20 μm, B-L, 50 μm.