Abstract

Polymers bearing dynamic covalent bonds may exhibit dynamic properties, such as self-healing, shape memory and environmental adaptation. However, most dynamic covalent chemistries developed so far require either catalyst or change of environmental conditions to facilitate bond reversion and dynamic property change in bulk materials. Here we report the rational design of hindered urea bonds (urea with bulky substituent attached to its nitrogen) and the use of them to make polyureas and poly(urethane-ureas) capable of catalyst-free dynamic property change and autonomous repairing at low temperature. Given the simplicity of the hindered urea bond chemistry (reaction of a bulky amine with an isocyanate), incorporation of the catalyst-free dynamic covalent urea bonds to conventional polyurea or urea-containing polymers that typically have stable bulk properties may further broaden the scope of applications of these widely used materials.

Differing from polymers formed with strong, irreversible covalent bonds and stable bulk properties, polymers prepared through reversible non-covalent interactions or covalent bonds exhibit interesting dynamic properties1–3. The dynamic features of reversible polymers have been employed in the design of self-healing, shape-memory and environmentally adaptive materials4–6. Non-covalent interactions are relatively weak with only a few exceptions such as quadruple hydrogen bonding7,8, high-valence metal chelation9,10 and host-guest interaction11,12. Dynamic covalent bonds, on the contrary, usually have higher strength and more controllable reversibility. Well-known dynamic covalent bonds or structures include hydrazone13, substituted cyclohexenes capable of retro-Diels-Alder reaction14 and thiol radical species amenable to radical association-dissociation15–17. These dynamic chemistries have been used in preparing polymers with unique properties and functions. For instance, self-healing materials, emerging functional materials that can heal the cut or crack with recovered mechanical property18, can be achieved not only through the release of the encapsulated or embedded healing reagents/catalysts19,20, but also through reversible exchange of non-covalent interaction21–28 or dynamic covalent bonding29–34 at the cut or crack interface. Recently, there has been growing interest in the design of dynamic covalent chemistry that can be incorporated with conventional polymers for self-healing application. Along this direction, Guan et al. developed a method to make dynamic poly(butadiene) by activating double bonds with the Grubb’s catalyst35,36. Leibler et al. synthesized dynamic polyesters with metal catalysts to accelerate high temperature esterification37,38. A few catalyst-free, low-temperature dynamic covalent chemistries have also been reported for the synthesis of reversible polymers32,33.

The amide bond forms the basic structure of numerous biological and commodity polymers (e.g., nylon, polypeptide, etc.) and, as such, is one of the most important organic functional groups. It has remarkable stability due to conjugation effects between the lone electron pair on the nitrogen atom and the π-electrons on the carbonyl p-orbital. Reversing the amide bond (amidolysis) usually requires extreme conditions (e.g., highly basic or acidic solutions and/or high temperature) or the presence of special reagents (e.g., enzymes)39. Introducing bulky substituents to an amide nitrogen atom has been reported to weaken the amide bond which results in amidolysis under mild conditions. The addition of a bulky group is believed to disturb the orbital co-planarity of the amide bond, which diminishes the conjugation effect and thus weakens the carbonyl–amine interaction (Fig. 1a)40. However, the dissociated intermediate from amidolysis (ketene), if formed, would be too reactive to show dynamic reversible formation of the amide bond. To make carbonyl-amine structures reversible, it is required that the dissociated carbonyl structure is stable under ambient conditions but still highly reactive with amines. One such functional group that satisfies these requirements is isocyanate. Isocyanate is reasonably stable under ambient conditions and can react with amines rapidly to form a urea bond, a reaction that has been broadly utilized in the synthesis of polyurea and poly(urethane-urea). Similar to the bulky amide bonds described above, urea bonds bearing a bulky group on the nitrogen atom can reversibly dissociate into isocyanate and amine, the reverse process of typical urea bond formation (Fig. 1b)41,42.

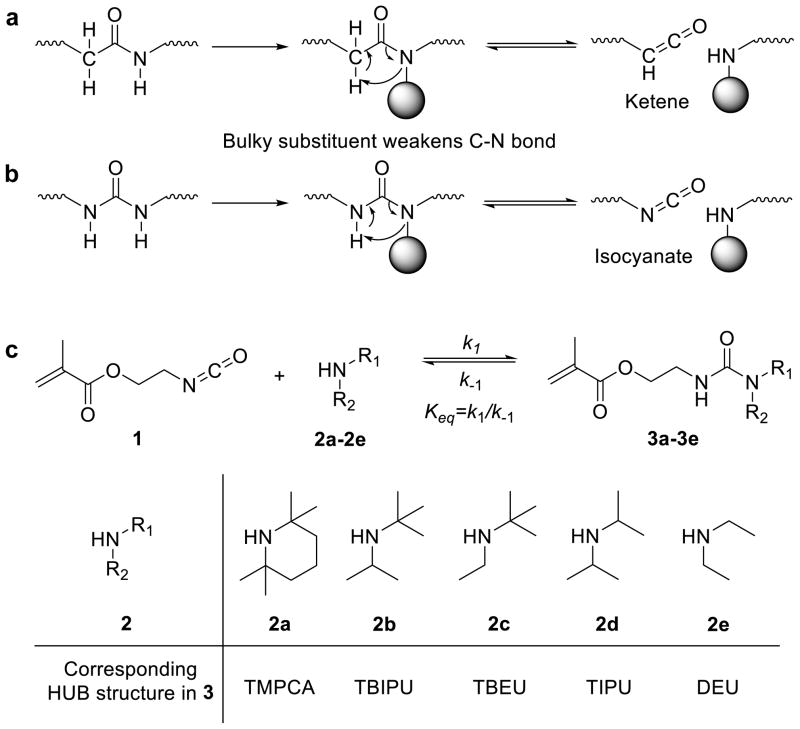

Figure 1. Dissociation of carboxylate/amine bonds bearing bulky N-substituent.

(a) Hindered amide bond dissociates to unstable ketene intermediate. (b) Hindered urea bond (HUB) dissociates to isocyanate, which is stable at low temperature but reactive to amine to reform the HUB bond, making HUB a dynamic covalent bond; (c) Equilibrium between isocyanate 1, bulky amines (2a–e) and corresponding ureas (3a–e), the chemical structures of bulky amines (2a–e), and the urea 3a–e bearing the corresponding HUB: 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinylcarboxyamide (TMPCA), N-tertbutyl-N-isopropylurea (TBIPU), N-tertbutyl-N-ethylurea (TBEU), N,N-diisopropylurea (DIPU) and N,N-diethylurea (DEU).

Here we report the design of dynamic hindered urea bonds (HUBs) and their application in the design and synthesis of polyureas and poly(urethanes-urea), some of the widely used materials in the coating, fibre, adhesive and plastics industries, that are capable of catalyst-free dynamic property change and autonomous repairing at low temperature.

Results

Design of HUBs and evaluation of their binding constants

Reversible chemistry does not necessarily lead to polymers with dynamic properties. To render reversible chemistry dynamic and practical for the synthesis of polymers with bulk properties, two criteria must be met. First, both the forward and the reverse reactions should be fast (large k1 and k−1, Fig. 1c). Second, the equilibrium must favour the formation of the polymer (large Keq = k1/k−1)43. In the design of dynamic polyurea, it is therefore crucial to identify a HUB with a properly selected substituent on the amine group so that the corresponding HUB can meet these two requirements.

We first performed equilibrium studies using 2-isocyanatoethyl methacrylate (1) and amines with different steric hindrance to identify such HUBs (Fig. 1c and Table 1). 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine (2a), a bulky amine containing two tert-butyl equivalent groups, was selected and mixed with 1 in CDCl3 in attempts to synthesize 3a bearing a HUB moiety—2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinylcarboxyamide (TMPCA) (Fig. 1c). As expected, TMPCA is reversible and the coexistence of 1, 2a and 3a was observed in CDCl3 based on 1H NMR analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, the three compounds were in thermodynamic equilibrium with a binding constant Keq of 88 M−1 at room temperature, independent of the concentration of 1 and 2a (Supplementary Figs 1–2). By reducing the substituent bulkiness on the amine by using N-isopropyl-2-methylpropan-2-amine (2b) to replace 2a, a larger binding constant was observed (Keq = 5.6 × 103 M−1, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 1). While the reversibility of 1-(tert-butyl)-1-isopropylurea (TBIPU), the corresponding HUB, is reduced compared to TMPCA and the reaction is more prone toward the formation of the urea bond, the Keq is still too small to be of practical use. If HUBs with such small Keq values were used in the design of polymers via condensation reactions, the resulting polymer would have a low degree of polymerization (DP) and limited bulk mechanical property43. Thus, although 3a and 3b are both reversible HUBs, they are clearly not the ideal dynamic bonds to be used in the preparation of dynamic polyureas with applicable bulk properties.

Table 1.

Equilibrium constant and dissociation rate of HUBs.

| HUB structure in 3 | TMPCA (3a) | TBIPU (3b) | TBEU (3c) | DIPU (3d) | DEU (3e) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keq (M−1) | 88 | 5.6×103 | 7.9×105 | >107 | >107 |

| k−1 (h−1) | - | - | 0.042(0.21a) | 0.0015a | 0.0011a |

Experiments performed at 37°C

To obtain a larger Keq, we further reduced the bulkiness of the N-substituents on the amine and used tert-butyl-ethylamine (2c), diisopropyl amine (2d) and diethylamine (2e) to react with 1 to prepare 3c–3e containing the corresponding HUBs: 1-(tert-butyl)-1-ethylurea (TBEU), 1,1-diisopropylurea (DIPU) and 1,1-diethylurea (DEU), respectively (Fig. 1c). These HUBs showed much larger binding constants than 3a and 3b (Keq = 7.9 × 105 for TBEU, Keq > 107 M−1 for DIPU and DEU, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 1). We went on to determine their dissociation constants (k−1) through intermediate trapping experiments (Supplementary Figs 5–7). As expected, 3c has the largest k−1 among these three HUBs (0.042 h−1 at room temperature, Table 1 and Supplementary Fig 5), while 3d and 3e have much smaller k−1 even at elevated temperature (Table 1). Because TBEU has both large Keq (k1) and k−1, we next designed experiments to study whether it could serve to control bond exchange and re-formation under mild conditions in TBEU-containing small molecules and polymers.

Dynamic exchange of HUBs in small molecules and polymers

We first studied the dynamic exchange of TBEU by mixing 3c with t-butylmethyl amine (2f), a compound with very similar N-substituent steric bulkiness as 2c. We monitored the ratio change of each compound in CDCl3 through 1H NMR. Although the concentration of 1, the isocyanate intermediate, was too low to be observed, t-butylmethyl urea (3f) and t-butylethyl amine (2c) were produced and detected by NMR. This observation verified the exchange reaction through the isocyanate intermediate 1 (Fig. 2a). As shown in Fig. 2b, the concentration of compound 3f and 2c increased over time while the concentration of compound 3c and 2f decreased until equilibrium was reached. Linear regression of the reaction kinetics proved the reversible exchange mechanism of these species (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 8). The time needed to reach complete equilibrium was about 20 h at 37 °C and the dissociation rate was determined to be 0.21 h−1 (t1/2 = 3.3 h) (Fig. 2c and Table 1). Thus, these experiments clearly demonstrated dynamic urea bond exchange in small molecules containing the TBEU moiety.

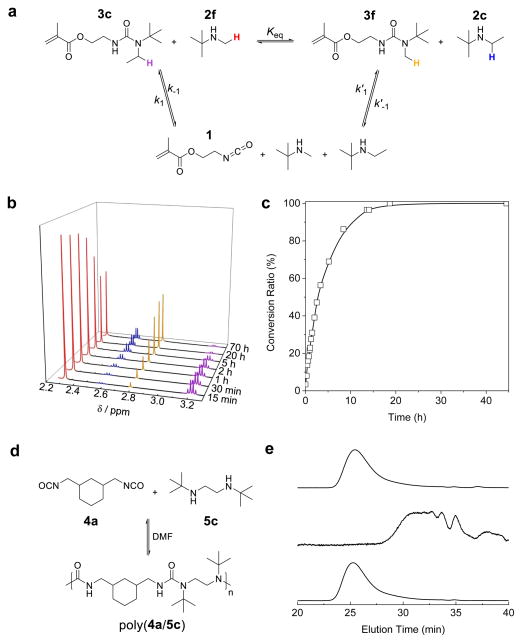

Figure 2. Dynamic exchange reactions in TBEU-bearing small molecule or polymer.

(a) Exchange reaction between 3c and 2f produces 3f and 2c with isocyanate 1 as the intermediate. (b) 1H NMR spectra after mixing 3c and 2f for different durations at 37°C. The proton peak intensities of 3c and 2f gradually decreased over time, along with the gradual increase of proton peak intensities of 3f and 2c until an equilibrium of the exchange reaction was reached at approximate 20 h. The protons subject to analysis from these four compounds were labelled with different colours in Fig. 2a, which correspond to the colours of peaks in Fig. 2b. (c) Conversion of 3c toward reaching equilibrium (Conversion ratio = ([3c]0 − [3c]t)/[3c]0 − [3c]eq, [3c]0 = initial concentration of 3c, [3c]t = concentration of 3c at time t, [3c]eq = equilibrium concentration of 3c). (d) Poly(4a/5c), TBEU-bearing dynamic polymers, prepared via the polycondensation of 4a and 5c. (e) Dynamic tuning of poly(4a/5c) shown by GPC analysis (signal from light scattering detector). Firstly, polymer solution was prepared by mixing 4a and 5c with [4a]0:[5c]0=1:1 ([4a]0 (or [5c]0) at 1.0 M in DMF), and the GPC experiment was performed after 2 h incubation at 37°C (upper curve). One additional equiv 5c was then added to tune the [4a]0:[5c]0 ratio to 1:2 and the GPC experiment was performed after 12 h incubation of the mixture at 37 °C (middle curve). Finally, one additional equiv 4a was added to restore the [4a]0:[5c]0 ratio back to 1:1. DMF was also added to keep [4a]0 (or [5c]0) at 1.0 M. GPC experiment was performed after 2 h incubation of the mixture at 37 °C (lower curve).

We next tested the dynamic behaviour of TBEU in polymers by mixing 1,3-bis(isocyanatomethyl)cyclohexane (4a) and N,N′-di-tert-butylethylenediamine (5c, a bisfunctional analogue of 2c) at 1:1 stoichiometry and [4a]0 (or [5c]0) concentration of 1.0 M in DMF (Fig. 2d). We used the β-branched diisocyanate 4a instead of a linear diisocyanate in order to increase the solubility of the corresponding polymers. Several HUBs formed with cyclohexanemethyl isocyanate (1″), a monofunctional analogue of 4a, have similar dynamic properties (especially nearly identical k−1) as those prepared from 1, indicating that β-substitution/branching of isocyanate has limited effect on dynamic property of HUBs (Supplementary Table 1). Poly(4a/5c) was formed with an Mn of 1.7 × 104 g/mol as analysed by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (see the mono-modal light scattering peak in the upper curve, Fig. 2e). The addition of another equivalent of 5c resulted in degradation of the polymer to very low molecular weight (MW) molecules after 12 h incubation at 37 °C (middle curve, Fig. 2e). Interestingly, when one equivalent 4a was added to the reaction solution to restore the 4a:5c ratio back to 1:1 (DMF was also added to keep [4a]0 (or [5c]0) at 1.0 M), the low MW light scattering peaks completely disappeared and a new, higher MW, monomodal GPC curve which overlays nearly perfectly with the original poly(4a/5c) GPC curve was observed (lower curve, Fig. 2e). In a separate experiment, we mixed two poly(4a/5c) samples with distinctly different MWs (Mn1 = 13.0 × 103 g/mol and Mn2 = 2.8 × 103 g/mol) in DMF solutions. After stirring the solution for 12 h at 37 °C, the two original GPC light scattering peaks disappeared and a new monomodal light scatting peak corresponding to an Mn of 4.8 × 103 g/mol was observed (Supplementary Fig. 9). These experiments demonstrate that the TBEU bonds are in fast dynamic exchange in both TBEU-containing small molecules and polymers. In several control experiments, we studied the condensation polymerization of 4a with bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidyl) sebacate (5a, a more bulky amine compared to 5c and a bisfunctional analogue of 2a) and N,N′-di-iso-propylethylenediamine (5d, a less bulky amine compared to 5c and a bisfunctional analogue of 2d). As expected, the mixture of 4a and 5a at 1:1 ratio in DMF only yielded very low MW polymer because of its low Keq (Supplementary Fig. 10). The mixture of 4a and 5d at 1:1 ratio in DMF yielded high MW polyurea (poly(4a/5d)) with very stable urea bond. No detectable dynamic bond exchange was observed when the formed poly(4a/5d) was treated with 5d at 37°C for 12 h (Supplementary Fig. 11). Thus, the dynamic change of HUBs can be controlled by tuning the steric bulkiness of the substituent attached to the urea bonds.

Synthesis and study of self-healing HUB-containing polymers

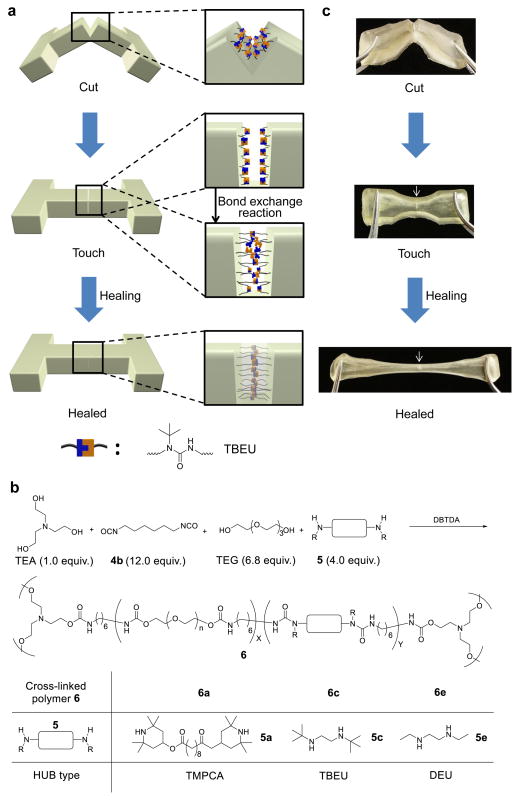

After demonstrating the dynamic property and bond exchange features of HUBs, we next attempted to use HUBs in the design of catalyst-free, low-temperature self-healing materials (as illustrated in Fig. 3a). Specifically, we designed cross-linked poly(urethane-ureas) containing HUBs and tested their self-healing property (Fig. 3b). Triethanolamine (TEA) was used as the cross-linker and tetra(ethylene glycol) (TEG) was used as the chain extender. Hindered diamines 5a, 5c and 5e were used to form the corresponding HUB motifs (TBEU, TMPCA and DEU) in the desired network polymers 6a, 6c and 6e, respectively. TEA, TEG and diamine were allowed to react with hexamethylene diisocyanate (4b) in DMF with dibutyltin diacetate (DBTDA) as the catalyst to yield cross-linked poly(urethane-urea)17. The molar ratio of TEA:4b:TEG:5 was set at 1:12:6.8:4 for the synthesis of the self-healing material. The cross-linking density (determined by the amount of TEA), dynamic moiety concentration (determined by the amount of 5) and polymer flexibility (determined by the amount of TEG) were optimized to ensure efficient self-healing with the optimal mechanical stiffness17. The hydroxyl and amine groups were included in excess of the isocyanate groups to improve the material stability against hydrolysis by increasing the free amine concentration (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figs 12–14).

Figure 3. Design of HUB-based self-healing materials.

(a) Illustration of the self-healing process of TBEU(N-tertbutyl-N-ethylurea)-based poly(urethane-urea). (b) Chemical structures and ratios of components used for the synthesis of HUB-based cross-linked poly(urethane-urea). (c) Selected snapshots during the course of the self-healing experiment of TBEU-based poly(urethane-urea) 6c. The cut pieces was gently pressed together and left to heal for 12 h at 37°C. The gel was then stretched. No fracture at the cut region was observed, showing efficient recovery of mechanical properties at the cut interface. The arrow indicates the position being cut.

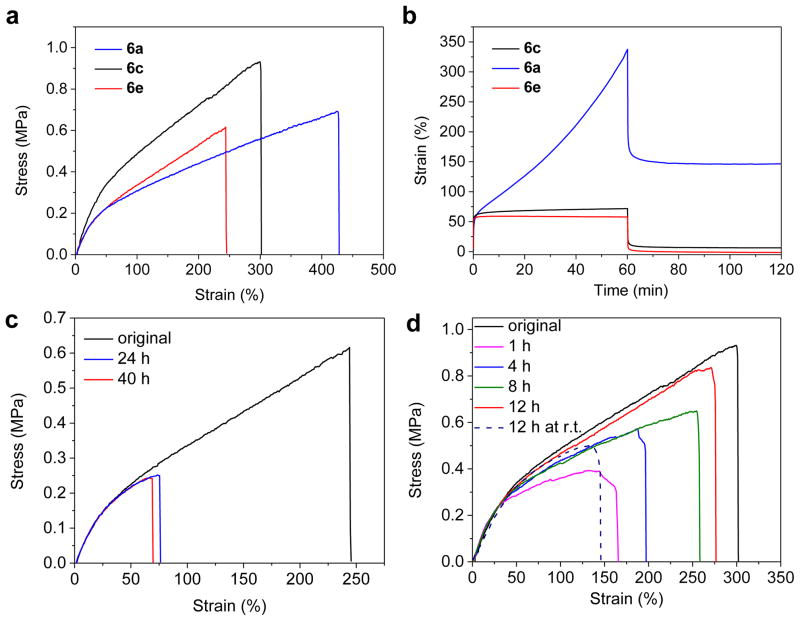

All three samples behaved as elastic gels with good mechanical stiffness (with Young’s modulus around 1 MPa, see Fig. 4a and Table 2) and thermal stability (Supplementary Fig. 15). They all have subambient glass transition temperatures (Tg, Supplementary Fig. 16), which provides sufficient chain mobility for bond exchange. Swelling experiments demonstrated that these polymers were cross-linked network. Both 6a and 6c could be dissolved in DMF containing 2f, substantiating the dynamic bond exchange property of the built-in HUBs (Supplementary Fig. 17). Next, we examined the creep-recovery behaviours to further understand the elastomeric property of these three samples (Fig. 4b)23,27. As expected, 6a showed completely different behaviour from 6c and 6e. When a stress of 0.08 MPa was applied to 6a and held for 60 min, the strain increased from 50% to ~350% (strain increase of 6.3% per min). After the stress was released, the gel could not return to its original length and had a residual strain as high as ~150% (blue trace, Fig. 4b). This phenomena can be explained by the weak strength of TMPCA bonds in 6a, thereby making the material behave like a physically cross-linked rubber that yields upon stretching. For 6e under the same condition, very slow strain increase was observed. After stress was released, the material recovered its original dimension with negligible residual strain (red trace, Fig. 4b). This experiment demonstrated that the DEU bonds in 6e are strong with very poor dynamic exchange property. Compared to 6e, 6c showed a slightly elevated strain increase (0.09% per minute) and residual strain (6%) (black trace, Fig. 4b), both of which were much smaller than those of 6a. This experiment showed that even with chain exchange, 6c is still strong enough to maintain satisfactory dimensional stability under externally applied stress.

Figure 4. Mechanical characterization of HUB-based cross-linked poly(urethane-urea).

(a) Stress-strain curves of 6a, 6c and 6e. (b) Creep-recovery of 6a, 6c and 6e with initial strain of 50%. (c) Inefficient recovery of the breaking strain of 6e after long period of healing. (d) Recovery of breaking strain of sample 6c under various healing conditions. The breaking strain of the cut and healed 6c was efficiently and largely restored after 12 h self-healing (87%) at 37°C. The healing at room temperature is less efficient (dotted line).

Table 2.

Physical properties of cross-linked poly(urethane-urea) with different HUBs.

| Tg (°C) | Young’s modulus (MPa) | Before cutting | After cutting and healing | Breaking strain recovery (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Breaking stress (MPa) | Breaking strain (%) | Breaking stress (MPa) | Breaking strain (%) | ||||

| 6a | −49 | 0.87±0.04 | 0.69±0.05 | 426±20 | / | / | / |

| 6c | −52 | 1.22±0.12 | 0.93±0.06 | 301±12 | 0.71±0.05 | 268±13 | 87±4 |

| 6e | −78 | 0.87±0.20 | 0.62±0.02 | 243±21 | 0.32±0.08 | 68±4 | 29±2 |

We next tested the self-healing behaviour of these three poly(urea-urethane) materials containing HUB moieties. We cured the polymers in a dog-bone shaped mould and cut the polymer as illustrated in Fig. 3a with a razor blade. We then gently brought the two pieces back in contact for 1 min and let the materials cure without external force and protection with inert gas. TMPCA-based 6a showed fast self-healing because of the highly reversible urea bond. After the two cut pieces were brought in contact for just 5 min at room temperature and stress was then immediately applied to the healed materials without further curing, strong reconnection of these two pieces and good recovery of mechanical strength were observed. However, complete recovery of the breaking strain in the self-repaired 6a can never be achieved. Because of the low binding constant (88 M−1, Table 1) and fast dynamicity of the TMPCA bonds, there should be substantial amount of free isocyanate groups in 6a without being used to form the TMPCA bonds. These free isocyanate groups are susceptible to hydrolysis, in particular for those at the surfaces of the cut pieces that are more exposed to the moisture in air, and irreversibly transform to amine groups after decarboxylation that can react with free isocyanate groups to form irreversible non-dynamic urea bonds. As such, 6a is expected to gradually lose self-healing property and prolonged healing is expected to lead to reduced instead of increased breaking strain, which was exactly what we have observed (Supplementary Fig. 18). We also noticed that the gel 6a was transparent initially but became turbid after several hours under ambient conditions, suggesting substantial material property change presumably due to the hydrolysis of the isocyanate groups.

Compared to 6a, 6e showed much slower healing as a result of its reduced dynamicity of the urea bonds (DEU, Fig. 3b). After a dog-bone shaped 6e was cut, the two pieces were brought back in contact and the polymer was allowed to heal for 24 h at 37°C, approximately 30% of the original breaking strain was recovered (Fig. 4c). Extended curing did not improve healing (red vs. blue trace, Fig. 4c). Stretching of the cured 6e resulted in fracture at the cut site.

Self-healing experiments with TBEU-based 6c revealed that this HUB has an advantageous balance of dynamicity (much large k-1 than that of DEU of 6e) and urea bond strength (much higher binding constant than that of TMPCA of 6a, Table 1). The self-healing experiment of 6c was similarly performed as 6a and 6e. The cut of 6c could self-heal at room temperature with moderately high recovery breaking strain (~50% after 12 h curing, dotted trace, Fig. 4d). At elevated temperature (37 °C), the materials showed much faster and better self-healing property. A breaking strain of 50% was recovered after putting the two cut pieces back in touch for 1 min and curing the materials for just 1 h. Longer curing time led to improved self-repairing and increased breaking strains (Fig. 4d). After 12 h of curing at 37 °C, the extensibility of the cured 6c had recovered 87% of its initial strain (Fig. 4d) and did not always fracture at the cut position (Supplementary Movie 1).

Discussion

Integrating dynamic moieties to polymers, especially those capable of dynamic covalent bonding in widely-used conventional polymers are of tremendous interest. In one particular application, for example, materials bearing such dynamic moieties may theoretically self-heal for unlimited times if the healing is directed by the reversible exchange of dynamic covalent bonds. However, bringing dynamic properties to conventional polymers often involves special dynamic moieties13–17 that may require tedious synthesis and/or use of external stimuli such as catalyst35,36 or high temperature37,38 for dynamic property activation and control. In this study we report the design of dynamic polyureas and poly(urethane-urea)s by attaching bulky substituents to the urea nitrogen to create the so-called hindered urea bonds (HUBs, Fig. 1). As HUBs are synthesized through the reaction of isocyanate and amine, conventional polyureas and poly(urea-urethane)s with stable bulky properties can thus be readily made dynamic by replacing regular amine with bulky amines (amines containing bulky substituents). By screening five HUBs with different substituent bulkiness, we identified N-tertbutyl-N-ethylurea (TBEU) as a promising HUB and successfully demonstrated its application in making dynamic polymers (Fig. 2e) and self-healing materials (Fig. 4d). Polymer chain reshuffling was observed for a linear polyurea based on TBEU (Fig. 2e). We incorporated TBEU moieties into a cross-linked poly(urethane-urea) to obtain catalyst-free self-healing materials under mild condition with good mechanical strength, dimensional rigidity and chemical stability. TBEU has a large Keq for retaining strong bonding and a reasonably large k−1 for efficient dynamic bond exchange under mild conditions (Table 1). Very bulky N-substituent in HUBs may result in faster dynamic bond exchange, as shown in the case of TMPCA, but its weak bond strength (smaller Keq, Table 1) makes it less favoured for self-healing applications (Supplementary Fig. 18). HUBs present a number of desirable properties for the synthesis of dynamic and self-healing polymers. They can be easily synthesized through the reaction of an isocyanate and a hindered amine, both of which are widely available and inexpensive. The dynamic properties of HUBs can be well controlled by adjusting bulkiness of the substituents. HUBs possess a hydrogen-bonding motif via its urea bond that can increase the mechanical strength of polymers, a property that most of other dynamic covalent chemistries lack. We anticipate that HUB structure and chemistry can be readily integrated in the design of a wide range of materials, bringing modular and tuneable dynamic properties to conventional polyureas and urea-containing polymers.

Methods

General

2-Isocyanatoethyl methacrylate was purchased from TCI America (Portland, OR, USA) and used as received. Anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) was dried by a column packed with 4Å molecular sieves. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) was dried by a column packed with alumina. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and used as received unless otherwise specified. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian U400 (400 MHz), a U500 (500 MHz) a VXR-500 (500 MHz), a UI500NB (500 MHz), or a UI600 (600 MHz) spectrometer. Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) experiments were performed on a system equipped with an isocratic pump (Model 1100, Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA), a DAWN HELEOS multi-angle laser light scattering detector (MALLS detector, Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) and an Optilab rEX refractive index detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). The detection wavelength of HELEOS was set at 658 nm. Separations were performed using serially connected size exclusion columns (100 Å, 500 Å, 103 Å and 104 Å Phenogel columns, 5 μm, 300 × 7.8 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) at 60 °C using DMF containing 0.1 M LiBr as the mobile phase. Creep-recovery experiments were performed on DMA Q800 (TA instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). Stress-strain experiments were performed on a custom built bi-directional screw driven rail table assembled by IMAC Motion Control Group (Elgin, IL, USA) with translation stage from Lintech (Monrovia, CA, USA), motor from Kollmorgen (Radford, VA, USA), load cell from Honeywell Sensotech (Columbus, OH, USA). Glass transition temperatures were tested by differential scanning calorimetry (Model 821e, Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA)

Synthesis of model hindered ureas 3b~3f

Urea compounds 3b~3f were synthesized by mixing 1 (1.0 mmol) with equal molar 2b~2f (1.0 mmol) in DCM (5 mL) at room temperature. After 1 h, the crude compound was purified by flash column with EtOAc as the eluent. Compounds 3b~3f were obtained quantitatively. Note: Because of the low binding constant, we could not get pure 3a under ambient condition.

2-(3-(tert-Butyl)-3-isopropylureido)ethyl methacrylate (3b)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.11 (dq, J = 1.6, 1.0 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 5.57 (dq, J = 1.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H, COC(Me)=CH2), 4.80 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.26 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H, O-CH2), 3.65 (h, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H, CH(CH3)2), 3.52 (q, J = 5.1 Hz, 2H, NH-CH2), 1.94 (dd, J = 1.0, 1.6 Hz, 3H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 1.32 (s, 9H, -C(CH3)3), 1.25 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H, -CH(CH3)2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.4, 160.1, 136.2, 126.0, 64.2, 56.3, 45.7, 39.5, 29.1, 23.4, 18.5. ESI-MS (low resolution, positive mode): calculated for C14H26N2O3, m/z, 271.2 [M + H]+; found 271.2 [M + H]+.

2-(3-(tert-Butyl)-3-ethylureido)ethyl methacrylate (3c)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.11 (dq, J = 1.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 5.58 (dq, J = 1.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 4.74 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.27 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H, O-CH2), 3.51 (q, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H, NH-CH2), 3.23 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, -CH2CH3), 1.94 (dd, J = 0.9, 1.6 Hz, 3H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 1.41 (s, 9H, -C(CH3)3), 1.15 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H, -CH2CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.8, 158.3, 136.3, 126.0, 64.4, 56.2, 40.2, 39.2, 29.7, 18.5, 16.6. ESI-MS (low resolution, positive mode): calculated for C13H24N2O3, m/z, 257.2 [M + H]+; found 257.2 [M + H]+.

2-(3,3-Diisopropylureido)ethyl methacrylate (3d)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.11 (dq, J = 1.7, 0.9 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 5.58 (dq, J = 1.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 4.57 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.27 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H, O-CH2), 3.89 (h, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, CH(CH3)2), 3.55 (q, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H, N-CH2), 1.94 (dd, J = 0.9, 1.7 Hz, 3H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 1.22 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 12H, CH(CH3)2). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.6, 157.1, 136.2, 126.0, 64.4, 45.1, 40.1, 21.5, 18.5. ESI-MS (low resolution, positive mode): calculated for C13H24N2O3, m/z, 257.2 [M + H]+; found 257.2 [M + H]+.

2-(3,3-Diethylureido)ethyl methacrylate (3e)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.09 (dq, J = 1.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 5.56 (dq, J = 1.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 4.74 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.25 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H, O-CH2), 3.51 (q, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H, N-CH2), 3.22 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H, -CH2CH3), 1.92 (dd, J = 1.6, 0.9 Hz, 3H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 1.10 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 6H, -CH2CH3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.7, 157.1, 136.2, 126.0, 64.3, 41.3, 40.4, 18.4, 13.9. ESI-MS (low resolution, positive mode): calculated for C11H20N2O3, m/z, 229.2 [M + H]+; found 229.2 [M + H]+.

2-(3-(tert-Butyl)-3-methylureido)ethyl methacrylate (3f)

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.10 (dq, J = 1.6, 0.9 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 5.56 (dq, J = 1.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 4.67 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, NH), 4.23 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H, O-CH2), 3.48 (q, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H, N-CH2), 2.79 (s, 3H, -CH3), 1.92 (dd, J = 0.9, 1.6 Hz, 3H, COC(CH3)=CH2), 1.37 (s, 9H, C(CH3)3). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.7, 159.0, 136.2, 126.0, 64.4, 55.7, 40.1, 31.7, 29.1, 18.4. ESI-MS (low resolution, positive mode): calculated for C12H22N2O3, m/z, 243.2 [M + H]+; found 243.2 [M + H]+.

Determination of equilibrium constants

Equilibrium constants at different initial ratios of amine and isocyanate

1 and 2a were dissolved in CDCl3 (0.5 mL) with three different ratios and added to the NMR tubes (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for details of the concentrations). 1H NMR spectra were collected 30 min after 1 and 2a were mixed at room temperature when equilibrium was reached (Supplementary Fig. 1). Concentration of each species was calculated based on the integral ratios of the 1H NMR signals and the initial concentrations of 1 and 2a. The equilibrium constants were calculated as:

| (1) |

Equilibrium constants at different temperatures

1 (8.5 mg, 0.055 mmol) and 2a (7.5 mg, 0.054 mmol) were dissolved in CDCl3 (0.5 mL) for NMR analysis. 1H NMR spectra were collected at different temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 2). Concentration of each species was calculated according to the integral ratios of 1H NMR signals and the initial concentrations of 1 and 2a. The equilibrium constants were calculated as equation 1.

Dissociation kinetics of TBEU, DIPU and DEU

Determination of dissociation rates of TBEU, DIPU and DEU

Butyl isocyanate (compound 1′) was added to 3c, 3d or 3e and the consumption rates of 3c, 3d or 3e were monitored by 1H NMR at room or higher temperature. The dissociation rates were calculated based on those data (Supplementary Figs 5–7).

Study of TBEU bond exchange with an amine

Urea 3c (11.3 mg, 0.044 mmol) that has a TBEU moiety and tert-butylmethylamine 2f (8.8 mg, 0.102 mmol) were mixed in CDCl3 (0.5 mL), quickly transferred to a NMR tube, and heated to 37°C. 1H NMR spectra were collected at selected time intervals until chemical equilibrium was reached.

Dynamic property of TBEU-based polymers

TBEU-based poly(4a/5c)

Equal molar 1,3-bis(isocyanatomethyl)cyclohexane (4a, 437 mg, 2.25 mmol) and N,N′-di-tert-butylethylene-diamine (5c, 387 mg, 2.25 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (2.0 mL). The mixture was stirred at 37 °C for 2 h vigorously and analysed by GPC to check if poly(4a/5c) was formed. Next, another equiv 5c (378 mg, 2.20 mmol) in DMF (0.90 mL) was added. The reaction was allowed to proceed for an additional 20 h. The solution was analysed by GPC to check if poly(4a/5c) was depolymerized to form oligomers at the [4a]0:[5c]0 ratio of 1:2. Finally, one equiv 4a (427 mg, 2.20 mmol) in DMF (1.05 mL) were added to the reaction solution to bring the [4a]0:[5c]0 ratio back to 1:1. Two hours later, the solution was analysed by GPC to check if higher molecular weight poly(4a/5c) was re-formed (Fig. 2e).

In another experiment, two batches of poly(4a/5c) were prepared. One polymer (poly(4a/5c)-1) was prepared by mixing 4a (338 mg, 1.74 mmol) and 5c (299 mg, 1.74 mmol) in DMF (1.5 mL) and the other polymer (poly(4a/5c)-2) was prepared by mixing 4a (338 mg, 1.74 mmol) and 5c (337 mg, 1.96 mmol) in DMF (1.5 mL). They were analysed by GPC with Mn of 13.0 × 103 g/mol and 2.8 × 103 g/mol, respectively. Next, equal volume (500 μL) of the solution of poly(4a/5c)-1 and poly(4a/5c)-2 were mixed and stirred vigorously at 37°C for 12 h. The mixture was analysed by GPC to verify if the polymer chain reshuffling happened which would result in a polymer with intermediate MW (lower than that of poly(4a/5c)-1 and higher than that of poly(4a/5c)-2) and monomodal GPC distribution (Supplementary Fig. 9).

TMPCA-based poly(4a/5a)

Equal molar of 1,3-bis(isocyanatomethyl)cyclohexane (4a, 152 mg, 0.78 mmol) and bis(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidyl) sebacate (5a, 376 mg, 0.78 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (1.0 mL). The mixture was stirred at 37 °C for 2 h vigorously and analysed by GPC (Supplementary Fig. 10).

DIPU-based poly(4a/5d)

Equal molar 1,3-bis(isocyanatomethyl)cyclohexane (4a, 203 mg, 1.05 mmol) and N,N′-di-iso-propylethylene-diamine (5d, 151 mg, 1.05 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (1.0 mL). The mixture was stirred at 37 °C vigorously for 2 h. The sample was analysed by GPC for the formation of poly(4a/5d). To the mixture was then added another equivalent 5d (153 mg, 1.06 mmol) with DMF (0.43 mL) to make the [4a]0:[5d]0 ratio 1:2. The reaction solution was stirred for 20 h and analysed by GPC (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Synthesis and study of self-healing HUB-containing polymers

Synthesis of 6a

In a typical experiment, hexamethylene diisocyanate (1.280 g, 7.6 mmol) and DMF (0.380 g, 15% weight ratio) were charged in a glass vial and cooled to 4 °C. Diamine 5a (1.220 g, 2.54 mmol) was slowly added to form oligo-urea. After the solution was brought to room temperature, TEA (0.094 g, 0.63 mmol) and TEG (0.829 g, 4.27 mmol) were added and the solution was vigorously homogenized. Then the pre-polymer was charged to a dog-bone shaped mould (dimension shown in Supplementary Fig. 19) followed by addition of dibutyl tin diacetate (DBTDA, 1 drop, ~10 mg). The polymer was allowed to cure at room temperature for 24 h under N2.

Synthesis of 6c

In a typical experiment, hexamethylene diisocyanate (1.380 g, 8.2 mmol) and DMF (0.317 g, 15% weight ratio) were charged in a glass vial and cooled to 4 °C. Diamine 5c (0.471 g, 2.74 mmol) was slowly added to form oligo-urea accompanied with significant heat release. After cooling the mixture to room temperature, TEA (0.102 g, 0.69 mmol) and TEG (0.897 g, 4.62 mmol) were added and the solution was vigorously homogenized. Then the pre-polymer was charged to a dog-bone shaped mould followed by addition of DBTDA (1 drop, ~10 mg). The polymer was allowed to cure at room temperature for 12 h and then at 60 °C for another 12 h under the protection of inert gas.

Synthesis of 6e

In a typical experiment, hexamethylene diisocyanate (1.450 g, 8.6 mmol) and DMF (0.707 g, 30% weight ratio) were charged in a glass vial and cooled to 4 °C. Diamine 5e (0.330 g, 2.84 mmol) was slowly added to form oligo-urea. After the solution was cooled to room temperature, TEA (0.107 g, 0.72 mmol) and TEG (0.939 g, 4.84 mmol) were added and the solution was vigorously homogenized. Then the pre-polymer was charged to a dog-bone shaped mould followed by addition of DBTDA (1 drop, ~10 mg). The polymer was allowed to cure at room temperature for 12 h and then at 60 °C for another 12 h under the protection of inert gas.

Swelling and amine-induced degradation of 6c

6c was immersed in DMF with or without the addition of amine 2f (2 equiv relative to TBEU bond in 6c), and then incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

Stress-strain experiments

Stress-strain experiments were performed on a custom-built bidirectional screw driven rail table that allows tensile testing of samples with both grips translating simultaneously and in opposite directions, keeping the centre of mass of the sample stationary. The samples were extended at the speed of 2 mm s−1. Load was measured via a 22 N capacity load cell.

Creep-recovery experiments

The samples were fixed by the grips, pulled to a certain strain (~50%) and held for 60 min. After that, the stress was released and the samples were allowed to relax for another 60 min.

Self-healing experiments

The samples were cut by a blade and then the cut pieces were gently pressed in touch for 1 min, left to heal at 37 °C for selected healing times without the protection of inert gas, and then subject to stress-strain experiments to test the recovery of their breaking strains.

Statistical analysis

Data are given as mean ± s.e.m.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the supports from the United States National Science Foundation (CHE 1153122) and the United States National Institute of Health (Director’s New Innovator Award 1DP2OD007246-01). We thank Professor Nancy Sottos for letting us use her laboratory equipment for the mechanical analysis of the polymer materials and Brett Beiermann in the Sottos group for training H.Y. to use the instrument and analyse the mechanical properties of the materials. We also would like to thank Catherine Yao for helping on preparing schematic illustrations.

Footnotes

Author contributions

H. Y. and J.C. planned the project and designed experiments. Y.Z. contributed to the project design. H. Y. carried out the experiments and collected data. H. Y. and J.C. analysed the experimental data, prepared figures and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecommunications

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permission information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Brunsveld L, Folmer BJB, Meijer EW, Sijbesma RP. Supramolecular polymers. Chem Rev. 2001;101:4071–4098. doi: 10.1021/cr990125q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowan SJ, Cantrill SJ, Cousins GRL, Sanders JKM, Stoddart JF. Dynamic covalent chemistry. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2002;41:898–952. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020315)41:6<898::aid-anie898>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehn JM. Dynamers: dynamic molecular and supramolecular polymers. Prog Polym Sci. 2005;30:814–831. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wojtecki RJ, Meador MA, Rowan SJ. Using the dynamic bond to access macroscopically responsive structurally dynamic polymers. Nat Mater. 2011;10:14–27. doi: 10.1038/nmat2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kloxin CJ, Scott TF, Adzima BJ, Bowman CN. Covalent Adaptable Networks (CANS): A Unique Paradigm in Cross-Linked Polymers. Macromolecules. 2010;43:2643–2653. doi: 10.1021/ma902596s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habault D, Zhang H, Zhao Y. Light-triggered self-healing and shape-memory polymers. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:7244–7256. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35489j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sijbesma RP, et al. Reversible polymers formed from self-complementary monomers using quadruple hydrogen bonding. Science. 1997;278:1601–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hentschel J, Kushner AM, Ziller J, Guan ZB. Self-Healing Supramolecular Block Copolymers. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:10561–10565. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burnworth M, et al. Optically healable supramolecular polymers. Nature. 2011;472:334–337. doi: 10.1038/nature09963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bode S, et al. Self-Healing Polymer Coatings Based on Crosslinked Metallosupramolecular Copolymers. Adv Mater. 2013;25:1634–1638. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harada A, Kobayashi R, Takashima Y, Hashidzume A, Yamaguchi H. Macroscopic self-assembly through molecular recognition. Nat Chem. 2011;3:34–37. doi: 10.1038/nchem.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakahata M, Takashima Y, Yamaguchi H, Harada A. Redox-responsive self-healing materials formed from host-guest polymers. Nat Commun. 2011;2:551. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skene WG, Lehn JMP. Dynamers: Polyacylhydrazone reversible covalent polymers, component exchange, and constitutional diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8270–8275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401885101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen XX, et al. A thermally re-mendable cross-linked polymeric material. Science. 2002;295:1698–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.1065879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott TF, Schneider AD, Cook WD, Bowman CN. Photoinduced plasticity in cross-linked polymers. Science. 2005;308:1615–1617. doi: 10.1126/science.1110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amamoto Y, Kamada J, Otsuka H, Takahara A, Matyjaszewski K. Repeatable photoinduced self-healing of covalently cross-linked polymers through reshuffling of trithiocarbonate units. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:1660–1663. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amamoto Y, Otsuka H, Takahara A, Matyjaszewski K. Self-Healing of Covalently Cross-Linked Polymers by Reshuffling Thiuram Disulfide Moieties in Air under Visible Light. Adv Mater. 2012;24:3975–3980. doi: 10.1002/adma.201201928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy EB, Wudl F. The world of smart healable materials. Prog Polym Sci. 2010;35:223–251. [Google Scholar]

- 19.White SR, et al. Autonomic healing of polymer composites. Nature. 2001;409:794–797. doi: 10.1038/35057232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toohey KS, Sottos NR, Lewis JA, Moore JS, White SR. Self-healing materials with microvascular networks. Nat Mater. 2007;6:581–585. doi: 10.1038/nmat1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palleau E, Reece S, Desai SC, Smith ME, Dickey MD. Self-healing stretchable wires for reconfigurable circuit wiring and 3D microfluidics. Adv Mater. 2013;25:1589–1592. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holten-Andersen N, et al. pH-induced metal-ligand cross-links inspired by mussel yield self-healing polymer networks with near-covalent elastic moduli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2651–2655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015862108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Kushner AM, Williams GA, Guan Z. Multiphase design of autonomic self-healing thermoplastic elastomers. Nat Chem. 2012;4:467–472. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang L, et al. Multichannel and repeatable self-healing of mechanical enhanced graphene-thermoplastic polyurethane composites. Adv Mater. 2013;25:2224–2228. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, et al. High-water-content mouldable hydrogels by mixing clay and a dendritic molecular binder. Nature. 2010;463:339–343. doi: 10.1038/nature08693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phadke A, et al. Rapid self-healing hydrogels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4383–4388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201122109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cordier P, Tournilhac F, Soulie-Ziakovic C, Leibler L. Self-healing and thermoreversible rubber from supramolecular assembly. Nature. 2008;451:977–980. doi: 10.1038/nature06669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fox J, et al. High-strength, healable, supramolecular polymer nanocomposites. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5362–5368. doi: 10.1021/ja300050x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh B, Urban MW. Self-repairing oxetane-substituted chitosan polyurethane networks. Science. 2009;323:1458–1460. doi: 10.1126/science.1167391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imato K, et al. Self-healing of chemical gels cross-linked by diarylbibenzofuranone-based trigger-free dynamic covalent bonds at room temperature. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:1138–1142. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adzima BJ, Kloxin CJ, Bowman CN. Externally triggered healing of a thermoreversible covalent network via self-limited hysteresis heating. Adv Mater. 2010;22:2784–2787. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reutenauer P, Buhler E, Boul PJ, Candau SJ, Lehn JM. Room temperature dynamic polymers based on Diels-Alder chemistry. Chem-Eur J. 2009;15:1893–1900. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oehlenschlaeger KK, et al. Fast and catalyst-free hetero-Diels-Alder chemistry for on demand cyclable bonding/debonding materials. Polym Chem. 2013;4:4348–4355. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng PW, McCarthy TJ. A Surprise from 1954: Siloxane Equilibration Is a Simple, Robust, and Obvious Polymer Self-Healing Mechanism. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2024–2027. doi: 10.1021/ja2113257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu YX, Guan Z. Olefin metathesis for effective polymer healing via dynamic exchange of strong carbon-carbon double bonds. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:14226–14231. doi: 10.1021/ja306287s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu YX, Tournilhac F, Leibler L, Guan Z. Making insoluble polymer networks malleable via olefin metathesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8424–8427. doi: 10.1021/ja303356z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montarnal D, Capelot M, Tournilhac F, Leibler L. Silica-Like Malleable Materials from Permanent Organic Networks. Science. 2011;334:965–968. doi: 10.1126/science.1212648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capelot M, Montarnal D, Tournilhac F, Leibler L. Metal-Catalyzed Transesterification for Healing and Assembling of Thermosets. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7664–7667. doi: 10.1021/ja302894k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basso A, De Martin L, Ebert C, Gardossi L, Linda P. High isolated yields in thermodynamically controlled peptide synthesis in toluene catalysed by thermolysin adsorbed on Celite R-640. Chem Commun. 2000:467–468. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutchby M, et al. Switching pathways: room-temperature neutral solvolysis and substitution of amides. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:548–551. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stowell JC, Padegimas SJ. Urea Dissociation. A Measure of Steric Hindrance in Secondary Amines. J Org Chem. 1974;39:2448–2449. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hutchby M, et al. Hindered Ureas as Masked Isocyanates: Facile Carbamoylation of Nucleophiles under Neutral Conditions. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:8721–8724. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao D, Moore JS. Nucleation-elongation: a mechanism for cooperative supramolecular polymerization. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:3471–3491. doi: 10.1039/b308788c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.