Abstract

Arterial endothelial phenotype is regulated by local hemodynamic forces that are linked to regional susceptibility to atherogenesis. A complex hierarchy of transcriptional, translational and posttranslational mechanisms are greatly influenced by the characteristics of local arterial shear stress environments. We discuss the emerging role of localized disturbed blood flow upon epigenetic mechanisms of endothelial responses to biomechanical stress, including transcriptional regulation by proximal promoter DNA methylation, and posttranscriptional and translational regulation of gene and protein expression by chromatin remodeling and noncoding RNA-based mechanisms. Dynamic responses to flow characteristics in vivo and in vitro include site-specific differentially methylated regions of swine and mouse endothelial methylomes, histone marks regulating chromatin conformation, microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs. Flow-mediated epigenomic responses intersect with cis and trans factor regulation to maintain endothelial function in a shear-stressed environment and may contribute to localized endothelial dysfunctions that promote atherosusceptibility.

Keywords: hemodynamics, atherogenesis, endothelial phenotype, epigenetics, DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, disturbed blood flow

Introduction

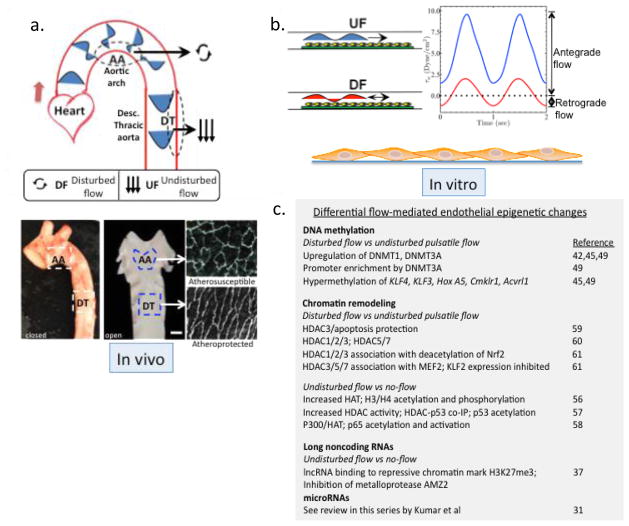

The interface between hemodynamics and the endothelium is profoundly important for the localization of atherosclerosis. Regional transient flow separations, flow reversals, and multidirectional oscillations, collectively referred to as disturbed flow, occur at and near arterial branches, bifurcations and vessel curvatures prone to the development of atherosclerotic lesions1,2. Disturbed arterial flow is associated with metabolic stress in the endothelium that sensitizes the cells to site-specific inflammatory and other pro-pathological changes3,4. In contrast, nearby regions of pulsatile unidirectional flow (undisturbed flow) are atheroprotected (Figure 1). Two broad flow-related mechanisms promote differential endothelial phenotypes at susceptible vs protected sites. First, different patterns of biomechanical cell deformation by hemodynamic forces, primarily shear stress5; regulate endothelial mechanotransduction pathways, and second, flow-related differences in the transport characteristics of labile peptides, metabolic intermediates and free radicals induce potent signaling interactions with the endothelium6,7. The mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. This ATVB in-Focus series (http://atvb.ahajournals.org/cgi/collection/biomechanical_stress_in_vascular_remodeling) is directed to recent advances in vascular cell and molecular responses to biomechanical stress. Several other reviews in the series8–10 discuss mechanisms of atherosusceptibility in relation to spatio-temporal hemodynamics. In our contribution we introduce and discuss emerging epigenomic and epigenetic mechanisms, particularly transcriptional regulation by DNA methylation, in the determination of arterial endothelial phenotype in regions of flow-mediated biomechanical stress and during exposure of endothelial cells to disturbed and undisturbed flow in vitro (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Disturbed and undisturbed flow. a. Site-specific disturbed blood flow in the aorta. Flow separation in the pig aortic arch (AA) defines an atherosusceptible site characterized by disturbed flow. Flow velocity vectors in the aorta illustrating flow separation with reversal in the inner curvature of the AA during the cardiac cycle. Unidirectional pulsatile flow (undisturbed flow) recovers in the atheroprotected descending thoracic (DT) segment. Endothelial morphologies are illustrated in situ at AA and DT locations. Endothelial cells are harvested from these sites for molecular analyses. b. Recapitulation of pulsatile undisturbed (UF) and disturbed (DF) flows for studies of human endothelial cells in vitro. c. Differential flow-mediated endothelial epigenetic changes.

Epigenetics

Epigenetics encompasses heritable changes in nuclear chromatin leading to gene expression changes that cannot be attributed to changes in the primary DNA sequence11. Inherited differences in phenotype that occur when the DNA sequence is identical or unchanging include, for example, differential characteristics of monozygous twins, the editing of gene expression essential for precursor cell differentiation through epigenetic gene silencing, progressive changes of chromatin function during normal aging, the normal development and pathological disruptions of neural circuits and the inactivation of the X chromosome in females12,13. Unlike the stable DNA code, the epigenomic code is dynamic12 with the potential to figure prominently in disease susceptibility and pathogenesis arising from environmental influences independent of, or in concert with, mutations and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) linked to many complex diseases including cardiovascular dysfunction14. Furthermore, a significant fraction of interspecies differences in gene expression are likely attributable to epigenetic variations arising from non-coding regions of the genome than to mutations in the coding genes14,15.

The efforts of the ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) and International Human Epigenome Consortia have uncovered thousands of new putative epigenetic regulatory mechanisms in the non-coding regions of the genome. The epigenome is essentially the interface between the genome and the environment. Hemodynamics is a constantly changing environment to which the arterial circulation is exquisitely sensitive through multiple mechanisms of gene regulation. Given the associative relationships between risk factors and cardiovascular disease, the interplay of mechanotransduction and epigenomic regulation of vascular phenotypes that may lead to novel therapeutic interventions warrants further investigation.

Epigenetic mechanisms

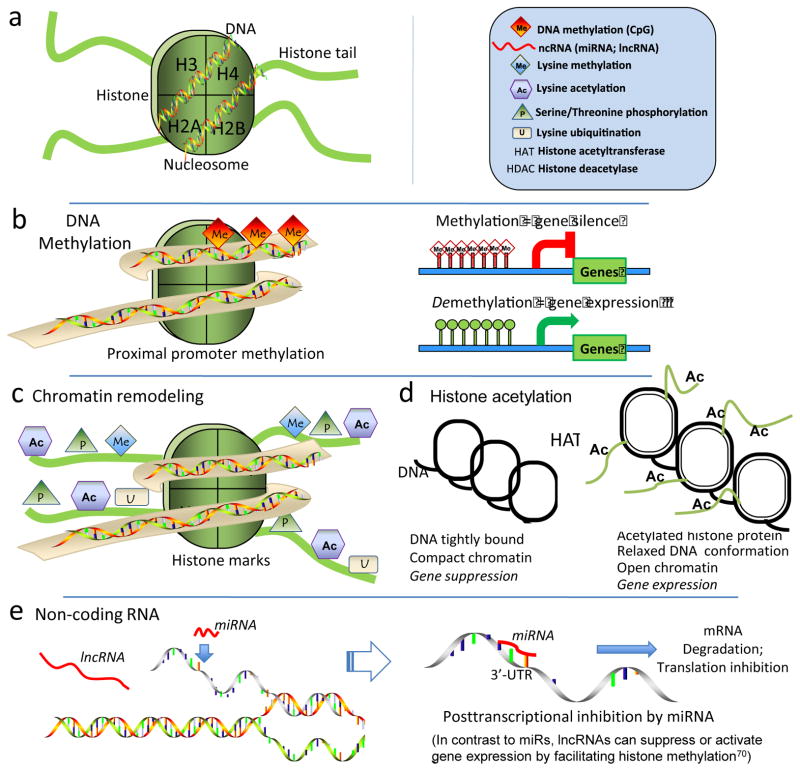

Three major groups of integrated epigenetic mechanisms regulate gene expression: DNA methylation, histone modifications and RNA-associated gene regulation (Figure 2). Several excellent integrated reviews of cardiovascular epigenetics14,16 in the literature include an epigenetics primer for vascular biologists17.

Figure 2.

Epigenetic mechanisms. a. Nucleosome structural elements. DNA is wrapped around each histone octomer protein that has basic amino acid-rich tail domains. b. Proximal promoter DNA methylation at CpG islands results in gene silencing by transcriptional repression. c. Posttranslational histone marks on N-terminal histone tails constitute a histone code; they include acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation and sumoylation that remodel chromatin by changing histone protein-DNA association which influences transcriptional regulation. d. Chromatin remodeling by HATs and HDACs. Histone acetylation relaxes tightly wound compact DNA to enable access of transcriptional regulators. HDACs deacetylate to restore compact chromatin and prevent transcription. e. Posttranscriptional RNA-based mechanisms include short (microRNAs) and long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). miRNAs usually target the 3′-untranslated region of mRNA promoting transcript degradation and also translation destabilization. lncRNA facilitate changes of histone methylation through complex mechanisms that can result in enhanced or repressed gene expression depending upon the histone mark.

DNA Methylation

DNA methylation is the methylation of the 5-carbon of cytosine residues (5-mC) in DNA usually at cytosine–phosphate-guanine dinucleotides (CpGs) sites18. Clusters of dinucleotides - CpG islands - are associated with approx 50% of gene promoters; they tend to be unmethylated, allowing transcription. Methylation of cytosines at or near the promoter region results in gene silencing by suppression of gene transcription19 (Figure 2b). Proximal promoter DNA methylation induces transcriptional silencing by preventing transcription factors from binding to the promoter or by inducing binding of methyl CpG binding proteins to methylated DNA20. During embryonic development/cell differentiation, DNA methylation status establishes properties of cell identity essential to define broad areas of development; however, a role for environmentally-induced DNA methylation in pathophysiology has emerged. Loss of DNA methylation as well as hypermethylation (silencing) of growth repressors in cancer are leading epigenetic characteristics of cell proliferation21. Dysregulation of gene expression in various disease states such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, neuropsychiatric disorders, homocysteinemia and senescence have been linked to aberrant methylation profiles22. DNA methylation can be evaluated in different functional contexts that range from cell identity to transcriptional activation, use of alternative promoter, transcription efficiency, mRNA splicing and dynamic regulation23, including the transcriptional regulation of some genes as part of the normal management of physiological homeostasis. As mechanisms regulating DNA methylation/demethylation have become better understood, a dynamic role for flow-related endothelial DNA methylation in vascular homeostasis and transition to pathology is emerging.

Central role of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs)

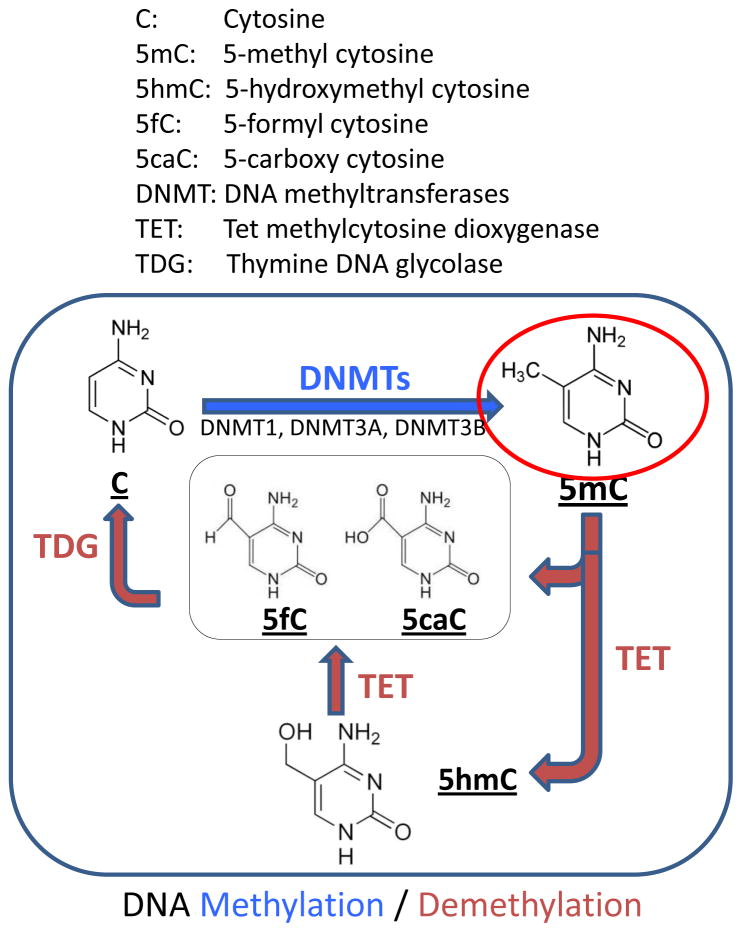

Three active mammalian DNA methyltransferases DNMT1, 3A and 3B promote methylation which is counterbalanced by DNA demethylation in which the TET (tet methylcytosine dioxygenase) pathway plays a central role24 (Figure 3). DNMT1 is primarily a maintenance enzyme to ensure fidelity of methylation pattern during somatic cell division. DNMT3A and 3B are closely related and, with their molecular partners, regulate de novo DNA methylation. Another methyltransferase DNMT3L lacks a catalytic activity and is inactive but may be important for the stabilization of DNMT3A and associated assembly complexes during de novo methylation in germ cells25. Although DNA methylation is generally stable, changes in the expression, targeting and activities of DNMTs and/or TET and their associated factors may alter the promoter methylation status of selective genes; it is unclear whether this is readily reversible. Identification of DNMTs in adaptive methylation in response to flow stimuli is discussed below.

Figure 3.

DNA methylation dynamics. In vertebrates, DNA methylation occurs at carbon 5 of cytosine (5mC) in CpG dinucleotides. Methylation of the promoter regions of genes dramatically suppresses transcription by direct inhibition of transcription factor binding and recruitment of methyl-CpG-binding proteins, which further hinder access to the recognition site of transcription factors. DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) maintains DNA methylation patterns during cell proliferation via methylation of a hemi-methylated nascent DNA strand. DNMT3A and DNMT3B are required for genome-wide de novo methylation and play crucial roles in the establishment of DNA methylation patterns. Methylation by DNMTs is counterbalanced by DNA demethylation. TET (ten-eleven-translocation) oxidizes 5mC to 5hmC and subsequently to 5fC and 5caC. The carboxyl group of 5caC is excised by TDG to restore cytosine.

Histone modifications

Histones are the principal proteins of the nucleosome, the stable chromosomal DNA-protein complex composed of ~146 bp of DNA wrapped around a histone octameric core26. The octameric core contains two copies of the histones H2A, H2B, H3 and H4, the amino terminal domains of which extend from the core as basic amino acid-rich ‘tails’ (Figure 2a). The arrangement of DNA as it winds around histones is instrumental in allowing or preventing transcription. The DNA-histone physical association is markedly affected by post-translational modifications of the tails primarily by acetylation/deacetylation and methylation of lysine residues. By influencing chromatin structure, histone acetylation and methylation determine the accessibility of transcriptional regulators to cis-DNA binding domains. Acetylation (of lysines) is usually permissive for transcription by relaxing DNA compaction whereas tightly condensed chromatin associated with deacetylated histone prevents DNA transcription11 as outlined for histone acetylation in Figure 2d. Histone acetylases (HAT) and deacetylases (HDAC) catalyze the net state usually in conjunction with multi-protein complexes.

Histone lysine and arginine N-terminal methylation is a posttranslational modification driven by histone-N-methyltransferases27. Each step requires a specific set of enzymes with various substrates and cofactors. Whether histone methylation prevents or promotes transcription is complex and is dependent on the combinations of particular methylated histone tail residues and their degree of methylation. Histone modifications or ‘marks’ are designated by the histone (H) and amino acid, e.g. lysine (K) combination and there are many permutations, e.g. H3K4 trimethylation (me3) and H3K27 methylation are transcription activating and repressing marks respectively. Although histone acetylation and methylation are most studied, other histone tail covalent modifications include serine phosphorylation and lysine ubiquitylation and sumoylation. The net effect of all of these modifications - believed to be in constant flux - is the accessibility to DNA of other regulatory proteins, cofactors and transcriptional inhibitors (Figure 2c).

RNA-associated gene regulation

DNA methylation and histone modifications cooperate in controlling gene expression. However a third important mechanism to add to posttranscriptional epigenetic regulation is that of RNA derived from non-coding sequences that can regulate gene expression through the activities of short interfering RNA (siRNA), microRNA (miRNA) and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA). Of these, miRNAs28 are the most extensively studied and play important roles in flow-induced responses of the endothelial cell both in vivo29,30 and in vitro10,31. miRNAs are highly-conserved noncoding small RNAs of 19–26 nucleotides that regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. Mammalian miRNAs usually bind to the 3′ untranslated region of target mRNAs, promoting mRNA degradation and/or inhibiting translation of the protein-coding genes28 (Figure 2e). Evolutionarily conserved Watson–Crick pairing between cognate mRNA 3′ UTR and miRNA 5′ regions centered on seed nucleotides (2–7nt) primarily determines miRNA target selection32. Individual miRNAs fine-tune the synthesis of many genes and miRNA-mediated proteomes are typically mirrored by transcriptomes. Given the widespread scope but modest repression of transcriptomes/proteomes by individual miRNAs, phenotypical consequences are likely achieved by coordinated actions on multiple targets by single miRNAs or integrated regulation of key pathways by multiple miRNAs33.

miRNAs in epigenetics

miRNAs function at the posttranscriptional level. There are many interactions between miRNAs, DNA methylation and chromatin remodeling34. miRNAs can be involved in establishing DNA methylation for example by targeting the key DNA methylation enzymes DNMT1, 3a, and 3b35. In turn, DNMT inhibitors such as 5-aza that inhibit DNA methylation can affect miRNA expression, e.g. upregulation of miR12736. Similar reciprocities were reported with respect to chromatin structure through miRNA regulation of key histone modifiers such as HDAC4; at the same time 4-phenylbutyric acid, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase, upregulated some miRNAs. Collectively, these miRNA epigenetic interactions represent complex dynamic regulation at multiple levels. It is likely that many of the flow-sensitive miRNAs identified to date contribute to epigenetic chromatin structure-function via mechanotransduction-specific DNA methylation and histone modifications.

miRNAs in flow

Flow-sensitive miRNAs, including mechanosensitive miRNAs implicated in atherogenesis, are reviewed by Kumar et al (2014)10 in this ATVB In-Focus series; these will not be further reviewed here. An earlier excellent review by Zhou et al (2011)31 that integrates shear stress-related miRNAs into epigenetics is also recommended.

lncRNAs

There is currently intense interest in epigenetic regulation by lncRNAs (>100 nucleotides) of which there are at least several thousand in the mammalian genome. Estimates are that each annotated gene is overlapped by ~10 isoforms that can interact with the biology of the cell at multiple levels and with great complexity via cis and trans targeting, enhancement, decoy, scaffold, conformational and coactivation/corepressor mechanisms15. Functional interpretation is difficult and frequently confounded by redundancies.

In contrast to miRNAs, lncRNAs are only recently under investigation in flow mechanotransduction. Interesting preliminary data were recently reported in abstract form37 demonstrating that shear stress (steady flow vs no-flow in vitro) regulates the expression of candidate lncRNAs in endothelial cells. Downstream effects on metalloprotease AMZ2 expression via lncRNA binding to the repressive chromatin mark H3K27me3 were reported.

Epigenetic changes in atherosclerotic lesions

Unsurprisingly, DNA methylation changes and chromatin structural modifications are readily detectable in atherosclerotic tissue. Administration of the HDAC inhibitor Trichostatin A (TSA) to LDLR−/− mice exacerbated atherosclerosis38. Unfortunately interpretation of cell-specific mechanisms is confounded by the comparison between complex lesions that develop in the arterial intima vs undiseased vessel wall composed almost entirely of medial smooth muscle cells. For example, a significant hypomethylation of CpG dinucleotides was measured in the coding region of extracellular superoxide dismutase from rabbit aortic atherosclerotic lesion when compared with normal intima-media39. However this likely reflects a comparison between monocyte-derived macrophages in the lesion vs the smooth muscle cell (SMC)-rich media in normal aorta. More instructive epigenetic data have been obtained when the tissue cell types can be identified or when in vitro manipulations of cell cultures can be used. Hiltunen and Yla-Herttuala (2003)40 likened atherosclerotic lesions to benign vascular tumors because of the proliferation and monoclonality of intimal SMC; they demonstrated the development of hypomethylation during transition of SMC from a contractile to a synthetic, proliferative state in vitro. Lund et al (2004)41 reported aberrant methylation patterns in apoE−/− mice aortas before any sign of lesion development and separately demonstrated that atherogenic lipoproteins induced global DNA hypermethylation in a human monocytic cell line. An important recent study by Dunn et al (2014)42 induced disturbed flow and subsequently atherosclerosis in mouse carotid artery, a vessel normally protected from lesion development. However, infusion of the pan-DNMT inhibitor 5-Aza-2-deoxycytidine (5-Aza) significantly reduced atherosclerosis suggesting an epigenetic mechanism linking disturbed flow and DNMT-mediated DNA methylation to overall lesion progression (expanded discussion below).

Endothelial methylome in vivo: Disturbed and undisturbed flow sites

Whole or partial genome sequencing of the endothelial DNA methylome in vivo provides a high-level view of site-specific differential methylation regions (DMRs) in endothelium in vivo without discriminating between developmentally stable epigenetics and that which may be under dynamic regulation. We performed comparative genome sequencing of endothelium from well-characterized arterial flow sites of disturbed (susceptible) and undisturbed (protected) blood flow in swine to create a DMR atlas. Using methylated DNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeDIP-seq) the genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in endothelial cells from pig aortic arch (athero-susceptible) and descending thoracic aorta (athero-resistant) were examined in detail. A total of 5517 DMRs with an average length of 804 ± 45 bp were identified in somatic chromosomes representing about 0.2% of the (swine) genome. 4019 regions were hypomethylated while 1498 regions were hypermethylated in aortic arch relative to thoracic aortia endothelium. Methylated regions and DMRs predominantly overlapped with gene- and CGI-rich regions. Enrichment in the 5′UTR suggests a functional role for DMRs in the transcriptional activity of genes. DMR-associated genes are involved in ER stress and superoxide radical degradation, pathways that have been identified as common features in disturbed flow atherosusceptible regions of swine arteries43,44. The association of DMRs with specific cytosines/CpG islands in and near the promoters of annotated genes provided insightful guidance for mechanistic experiments. MeDIP-seq experiment annotation and data have been uploaded into ArrayExpress (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/) with accession number E-MTAB-1930 and into the European Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) with accession ERP004025.

Flow characteristics have been successfully manipulated in mouse carotid arteries by selective ligation of branch arteries. Dunn et al (2014)42 introduced disturbed flow in a normally undisturbed flow region to demonstrate upregulation of DNMT1 in endothelium. Using partial genome sequencing they identified hypermethylation of a subset of potentially important endothelial molecules, including transcription factors, by cross-referencing transcriptomic and DNA methylomic datasets. Several DMRs in the promoters of the gene subset contained cyclic AMP Response Elements (CRE) sites that were hypermethylated suggesting a possible cooperative regulatory role for CRE binding protein. Using in situ immunostaining protocols in rats, Zhou et al (2014)45 also reported increased endothelial DNMT1 expression and enhanced DNA methylation in partially ligated mouse carotid arteries.

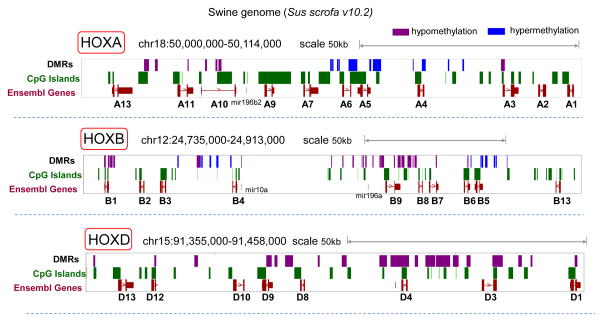

DMR and HOX genes in vivo

DMR comparisons between athero-susceptible and protected sites in normal swine methylome revealed a sharp distinction in the HOX loci (Figure 4). These loci are associated with previously identified differentially expressed HOX genes, including HOXA4/5/7/10/11, HOXB5/6/7/13, HOXD104 and the regulatory microRNA mir-10a/b29. HOX transcription factors, master regulators of body patterning46, have been reported to specify cell identity and position in arterial blood vessels47. The HOX genes regulate endothelial cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, morphogenesis and permeability during development and vascular remodeling in adults. HOXA3/9, HOXB3/5 and HOXD3 regulate endothelial cell activation, whereas HOXA5 and HOXD10 sustain quiescent endothelial phenotype and are increased during the maturation of endothelial cells48. HOXA3 and HOXD3, which promote a proliferative and migrative phenotype, are induced in the early phase of endothelial differentiation.

Figure 4.

The UCSC Genome Browser (Sus scrofa v10.2) was used to visualize differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and CpG islands at HOXA, B and D loci (chr18, chr12 and chr15 respectively). DMRs are shown as blue and purple regions, which represent hypermethylation and hypomethylation in aortic arch respectively (n=12, FDR<0.1).

Endothelial DMR and HoxA5 gene expression were also linked in vivo following induction of disturbed flow in carotid artery of apoE−/− mice42, possibly by enhanced DNMT1 expression; 5Aza inhibited HoxA5 hypermethylation. Of eleven mechanosensitive genes whose promoters were hypermethylated under disturbed flow conditions in this mouse study, HoxA5 was robustly silenced by DNA methylation and rescued by 5-Aza. It is noteworthy that HoxA5 was the most hypermethylated DMR and the most suppressed Hox transcript in steady state disturbed flow in swine aortic arch endothelium. Collectively these DMR studies in pigs and mice identified endothelial Hox genes, and specifically HoxA5, as putative DMR-sensitive epigenomic targets associated with site-specific disturbed flow in vivo. Regulation of endothelial HOX gene expression by DNA methylation may underlie important regulatory mechanisms of regional endothelial diversities in the cardiovascular system and some, such as HoxA5, may show selective plasticity to flow characteristics.

Flow-induced plasticity of endothelial DNA methylation in vitro

Changes in DNMT1 and DNMT3A by disturbed flow in vitro

The application of different flow characteristics to cultured human arterial and umbilical vein endothelial cells (HAEC and HUVEC respectively) allows mechanisms of disturbed and undisturbed flow to be addressed under controlled and accessible conditions. Flow waveforms that capture the dominant characteristics of human arterial hemodynamics can readily be generated in vitro1,2 (Figure 1). All flow in large arteries is unsteady (pulsatile). The defining feature of disturbed flow regions is the presence of a flow reversal phase during the cardiac cycle – sometimes referred to as oscillating shear – that creates multidirectional flow vectors within complex laminar flow regions. In contrast, undisturbed flow accelerates and decelerates the blood always in the antegrade direction. Recapitulation of arterial flow characteristics in vitro show HUVEC DNMT1 transcript and protein expressions to be significantly upregulated by disturbed flow42. Monocyte adhesion, a functional in vitro assay for pro-inflammatory activation, was significantly enhanced. Inhibition of DNMTs by 5-Aza and siRNA (directed to DNMT1) inhibited monocyte adhesion to HUVEC. Other DNMTs were unchanged by disturbed flow. Zhou et al (2014)45 also exposed HUVEC to disturbed flow; DNMT1 mRNA was increased 1.9-fold and immunocytochemistry revealed enhanced nuclear localization of DNMT1 in disturbed flow. Immuno-slot blot indicated an overall increased methylation by disturbed flow at 24h. However, in HAEC subjected to disturbed and undisturbed flow waveforms for 48h Jiang et al (2014)49 reported no significant changes in mRNA expression of the methyltransferases DNMT1, 3A, and 3B, nor enzymes involved in cytosine demethylation – TET1, 2, 3; TDG1; GADD45B; MBD4; SMUG1 – following exposure to disturbed flow; DNMT3L expression was undetectable. However, a significant increase in DNMT3A protein was detected. An increase in DNMT3A protein without change of the mRNA levels suggests a post-transcriptional and/or post-translational mechanism (eg. sumoylation)50 of DNMT3A regulation by flow.

After specific genes are shown to be methylated by disturbed flow, it is necessary to conduct detailed studies assessing the methylation status of individual CpG sites in the promoter and gene body sequences. This approach has recently been described for the important endothelial transcription factor Kruppel-like Factor 4 (KLF4)49.

DMR and Kruppel-like factor 4

KLF4 is a member of the zinc-finger regulatory transcription factor family; it targets gene networks that confer atheroprotective51, anti-inflammatory52 and anti-thrombotic53 properties to the endothelium. Localized dysfunction and suppression of KLF4 are therefore pro-pathological and are characteristic of atherosusceptible endothelium at sites of disturbed flow in vivo49. Since endothelial nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and thrombomodulin (THBD) are downstream targets of KLF4, its suppression in endothelium may have important downstream pro/anti-inflammatory consequences. Having identified an endothelial DMR site close to the promoter of KLF4 that was hypermethylated in the atherosusceptible aortic arch of swine, Jiang et al (2014)49 exposed HAEC to disturbed flow in vitro for 48h to demonstrate hypermethylation of the human KLF4 promoter when compared to undisturbed flow. Differential CpG site methylation was measured by methylation specific PCR (MSP), bisulfite pyrosequencing and methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme-PCR. Disturbed flow increased DNA methylation of CpG islands within the KLF4 promoter, significantly contributing to suppression of KLF4 transcription. The DNMT inhibitors 5-Aza and RG108 prevented disturbed flow-induced methylation of the KLF4 promoter, extending 1.5kb upstream of the transcription start site (TSS). As noted above, disturbed flow induced a modest increase of DNMT3A protein in HAEC. However, when chromatin loading of DNMT3A enzyme at the KLF4 promoter was examined by ChIP-PCR assay, a specific 11-fold DNMT3A enrichment of the KLF4 promoter was identified in disturbed flow over undisturbed flow49. TET1 enrichment was equivalent in disturbed and undisturbed flow.

The human KLF4 promoter contains a single myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) binding site. To test if hemodynamic forces could regulate the methylation status of CpG in and near the MEF2 binding sequence, the methylation levels at individual CpG sites were measured by bisulfite pyrosequencing. Disturbed flow further enhanced CpG methylation close to the MEF2 binding sequence49. Consistent with this, disturbed flow reduced the chromatin loading of MEF2 protein to the KLF4 promoter by 80%, confirming that MEF2-enhanced KLF4 gene transcription is impeded by methylation of the KLF4 promoter. Sustained knock-down with shDNMT3A blocked methylation of the MEF2 binding region, demonstrating DNMT3A specificity. Thus competitive inhibition by DNMT3A-mediated hypermethylation of a MEF2 binding region in the KLF4 promoter near the TSS significantly contributes to transcriptional suppression of KLF4 in disturbed flow as outlined in Figure 5.

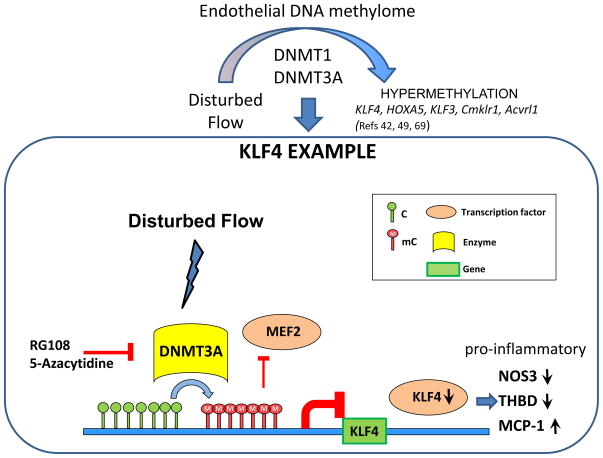

Figure 5.

Disturbed flow influences endothelial DNA hypermethylation via DNMT142,45 and DNMT3A49 pathways. A mechanism regulating KLF4 promoter methylation that contributes to suppression of transcription49 is illustrated. Disturbed flow-induced DNMT3A enrichment of endothelial KLF4 promoter near the TSS increases CpG methylation. The resulting hypermethylation of KLF4 promoter induces gene silencing by preventing the chromatin binding of MEF2 to the KLF4 promoter. Decreased KLF4 expression inhibits its transcription targets Thrombomodulin (THBD) and Nitric Oxide Synthase 3 (NOS3) and de-represses expression of Monocyte Chemoattractant Factor-1 (MCP-1) leading to a pro-inflammatory, pro-atherosclerosis phenotype. Intervention by DNMT inhibitors (RG108; 5-Azacytidine) rescues this pathway. Cmklr1: chemokine-like receptor 1 ; Acvrl1: activin receptor-like kinase 1.

The above mechanisms have downstream consequences for KLF4 transcription targets. Disturbed flow-induced KLF4 hypermethylation in HAEC inhibited the athero-protective expression of NOS3, THBD and upregulated pro-inflammatory MCP-1 (which is normally inhibited by KLF4)49 (Figure 5). All 3 genes are KLF4-targets and appear to be resistant to changes of DNA methylation. For example, the resilience of the human NOS3 gene to hypermethylation is attributed to its hypomethylated status being a critical determinant of endothelial cell identity established during development54. Other EC-restricted genes17,55 may also be more readily regulated by pleiotropic transcription factors that are sensitive to transcriptional regulation by DNA methylation.

Flow-mediated endothelial HDAC/HAT activity in vitro

Prescient in vitro experiments by IIli et al (2003)56 first established the molecular basis for epigenetic histone modification by shear stress in endothelial cells. The application of laminar shear stress to HUVECs activated histone H3 phosphorylation and acetylation and H4 acetylation that were further increased by the HDAC inhibitor TSA. Flow stimulated CREB/CBP transcriptional complex formation that resulted in enhanced HAT activity; the HAT/HDAC balance presumably determines net acetylation. Selective inhibition studies suggested that the flow-dependent phosphorylation and acetylation of histones were independently regulated by different signaling pathways. Parallel experiments on chromatin remodeling by growth factors in the same study suggested that although shear stress and growth factors may share signaling pathways, histone modifications remain distinct to each stimulus.

Zeng et al (2003)57 investigated the mechanisms by which flow regulates p53 and p21Waf1 in endothelial cells. Laminar flow suppression of endothelial cell cycle at the transition from the G1 to S phase is associated with an increase in the expression of p21Waf1. Undisturbed laminar flow led to an increase in p53 acetylation at Lys-382 but a deacetylation at Lys-320 and Lys-373 contributing to the activation of p21Waf1. HDAC1 co-immunoprecipitated with p53 and HDAC activity of the immunoprecipitate was increased significantly by laminar flow.

Chen et al (2008)58 demonstrated that the binding of NFkB subunits p50 and p65 to NOS3 promoter by steady undisturbed flow was dependent on activation of p300/HAT that acetylates p65 and histones close to the NOS3 shear stress response element. P300/HAT activation was essential for increased NOS3 transcription, an important protective response associated with undisturbed laminar flow. Inhibition or knockdown of p300/HAT completely prevented shear-induced NOS3 increase.

The above studies compared static conditions to simple laminar flow rather than measurements of disturbed flow vs undisturbed flow analogous to arterial flow in vivo (which is never static). The first comparative study of disturbed flow effects on HDAC activity arose from immunohistochemical staining of endothelial HDAC expression in situ. Having noted by immunostaining that HDAC3 expression of mouse arterial endothelial cells was enhanced near branches (disturbed flow), Xu and colleagues (2010)59 demonstrated that disturbed flow, but not undisturbed shear stress, increased HDAC3 expression in HUVEC. Neither flow profile increased deacetylase activity. HDAC3 knockdown, however, promoted apoptosis. Stabilization of HDAC3 in disturbed flow was potentiated by a strengthening of a complex formed between HDAC3 and the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt via increased phosphorylation of HDAC3. Overexpression of HDAC3 upregulated Akt phosphorylation and Akt kinase activity, and overexpression of Akt partially rescued the HDAC knockdown-induced apoptosis. Therefore disturbed flow-induced HDAC3 appears to protect against apoptosis, promoting cell survival in a complex biomechanical stress environment.

Lee et al (2012)60 expanded the involvement of HDACs in endothelial responses to flow, demonstrating that disturbed flow characteristics increase expression and activities of multiple HDACs. In direct comparisons of oscillatory and pulsatile undisturbed (unidirectional) shear stress, the expression and nuclear accumulation of HDAC1/2/3 and HDAC5/7 was upregulated in disturbed flow whereas undisturbed flow promoted nuclear export of HDACs 5 and 7. Immunostaining in rat aortic arch and in a stenosed disturbed flow region of abdominal aorta identified local HDAC2/3/5 expression. HDAC1/2/3 are also involved with endothelial atheroprotection through regulation of oxidative status. KLF2 and the antioxidant transcription factor NF-E2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) are upregulated by undisturbed flow but suppressed by disturbed flow; these transcription factors are estimated to regulate a significant fraction of atheroprotective shear stress-induced gene sets in endothelium61. Nrf2 binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) in the promoter region of antioxidant genes, including NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1), to induce their expression62. Co-immunoprecipitation demonstrated that disturbed flow increased the association of Nrf2 with HDAC-1/2/3 resulting in deacetylation of Nrf2, reduced binding to NQO1 ARE, lowered expression of NQO1 and consequently greater susceptibility to oxidative stress61. A similar approach demonstrated a disturbed flow-induced HDAC 3/5/7 association with MEF2, a transcription factor that binds to the KLF2 promoter; deacetylation of MEF2 led to inhibition of KLF2 expression.

Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a NAD-dependent histone deacetylase that protects against oxidative stress by deacetylating forkhead transcription factors63,64 and p5365, thereby inhibiting their ability to induce apoptosis, is also implicated in flow-mediated endothelial regulation of eNOS66. Pulsatile unidirectional undisturbed flow induced SIRT1 deacetylase activity in HUVECs whereas expression was unchanged by disturbed flow (oscillating shear stress). Consistent with the in vitro findings, endothelial SIRT1 expression in the undisturbed region of mouse thoracic aorta was elevated in comparison to the aortic arch (disturbed flow). Sirt1 elevation was linked to increased mitochondrial biogenesis and its attendant key regulators. SIRT1 was shown to associate with eNOS resulting in deacetylation and increased availability of nitric oxide. Since disturbed flow is associated with chronically increased ROS and oxidative stress induces SIRT1, why is SIRT1 not elevated in disturbed flow? Chen et al (2010)66 suggest that in contrast to oscillatory disturbed flow, pulsatile undisturbed flow has a transitory effect on ROS elevation that is more effective in inducing SIRT1. Consistent with this idea is that short exposure to hydrogen peroxide induces SIRT1 whereas longer exposure does not. They suggest that high ROS levels in disturbed flow activate poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) resulting in NAD+ depletion that inhibits SIRT1. Although further clarification of these competing mechanisms in a very complex cell survival scenario is warranted, it is nevertheless clear that atheroprotected regions of mouse aorta express much higher levels of SIRT1 than the atherosusceptible aortic arch despite much higher ROS in the arch.

Perspectives

The endothelium is a dynamic complex metabolic interface, the biology of which is exquisitely sensitive to local biophysical forces generated by constantly flowing blood. Flow separation-induced disturbances result in adaptive cellular responses that predispose the artery to atherogenesis at specific sites but do not induce pathology unless accompanied by additional risk factors. Instead, susceptibility is related to the chronic adaptation of cellular phenotype that allows continuation of the major functions of endothelium. Whether this is dysfunction or an adaptive resetting of the rate constants for many different cellular pathways (allowing an extended but still normal range of functional activity) is a semantic point. Susceptible phenotype matters because it is the template that determines transition to pathology whereas elsewhere the artery wall is protected against lesions either by the absence of susceptibility or the presence of additional specific protective mechanisms.

There have been extensive cell and molecular studies of biomechanical responses in endothelial cells. Many have investigated the effect of simple (often steady) flow vs no-flow for which there is no arterial flow equivalent; yet, remarkably, pathways and major regulatory molecules have been identified of great relevance to regional arterial differences in vivo, e.g. KLF267. More recently, flow characteristics in vitro and in vivo are being closely matched to allow direct comparison of disturbed vs undisturbed flow. Furthermore, with advances in 4-dimensional flow visualization and computation68, the dynamic environment of endothelium at specific arterial sites is established. Cell phenotype profiles obtained from in vivo sites can then be used to establish candidate targets of interest for in vitro investigations; e.g. microRNAs28,31. Access to efficient and economical sequencing methodologies has expanded the opportunities to analyze flow-related regulation of endothelial biology in great detail. While it was realized a decade ago that epigenetic/epigenomic pathways can regulate endothelial responses to shear stress, only relatively recently has the emergence of ENCODE and the Human Epigenome Consortium revealed the vast potential of dynamic epigenomic regulation of gene expression, including that by physical stimuli such as biomechanical stress. The recent demonstrations of endothelial KLF4 and HOXA5 proximal promoter DNA hypermethylation by disturbed flow are an emerging epigenomic mechanism69 of flow-associated transcriptional regulation to add to posttranscriptional regulation by histone remodeling and non-coding RNAs. Further studies will determine if transcriptional regulation by DNA methylation plasticity to flow is common at the many DMRs identified in the endothelial methylome. Collectively, epigenetics has greatly expanded our understanding of the complex hemodynamic-arterial endothelial biology interface and its role in susceptibility to cardiovascular disease.

Significance.

The distribution of atherosclerosis is closely associated with arterial branches, bifurcations and curvatures where the blood flow creates local complex flow reversals in vortices and eddies, collectively referred to as disturbed flow (DF). DF sensitizes the endothelium to the initiation of atherosclerosis if/when risk factors are added. DF sites are ‘atherosusceptible’, a pre-pathological state of stress adaptation to the local hemodynamic environment. Many endothelial transcription factors, co-activators and repressors are responsive to the biomechanical stresses associated with flow and contribute to the DF phenotype. Epigenetic mechanisms are also powerful regulators of gene expression and are flow-sensitive. Flow characteristics mediate endothelial gene expression by epigenomic DNA methylation of promoters, post-transcriptional histone modifications, and non-coding RNA-based mechanisms. We summarize recent evidence of hemodynamic regulation of endothelial gene expression by epigenomic mechanisms that contribute to the atherosusceptible endothelial phenotype, its function and dysfunction. Furthermore, the complex epigenomic mechanisms represent potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

Supported by AHA Postdoctoral Fellowship 13POST14070010 (Y-ZJ), NIH grant P01 HL62250 from the National Heart Lung & Blood Institute (PFD, EM), NIH grant K25 HL107607 (JMJ), andthe Robinette Foundation Endowed Professorship in Cardiovascular Medicine (PFD).

Abbreviations

- 5-Aza

5-Aza-2-deoxycytidine

- 5hmC

5-hydroxymethylcytosine

- 5mC

5-methylcytosine

- CpG

cytosine–phosphate-guanine dinucleotides

- DF

disturbed flow

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- DMR

differential methylation regions

- ENCODE

Encyclopedia of DNA Elements

- HAEC

human aortic endothelial cell

- HAT

histone acetylases

- HDAC

histone deacetylases

- HOX

homeobox gene

- KLF4

Kruppel-like factor 4

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- miRNA

microRNA

- NOS3

nitric oxide synthase 3

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

- TET

Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase

- TSA

Trichostatin A

- UF

undisturbed flow

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Davies PF. Hemodynamic Shear Stress and the Endothelium in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. Nature Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:16–26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu JJ, Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis of and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:327–387. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00047.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajra L, Evans AI, Chen M, Hyduk SJ, Collins T, Cybulsky MI. The NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway in aortic endothelial cells is primed for activation in regions predisposed to atherosclerotic lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9052–9057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Passerini AG, Polacek DC, Shi C, Francesco NM, Manduchi E, Grant GR, Pritchard WF, Powell S, Chang GY, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Davies PF. Coexisting proinflammatory and antioxidative endothelial transcription profiles in a disturbed flow region of the adult porcine aorta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2482–2487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305938101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies PF. Flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:519–560. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dull RO, Tarbell JM, Davies PF. Mechanisms of flow-mediated signal transduction in endothelial cells: Kinetics of ATP surface concentrations. J Vasc Res. 1992;29:410–419. doi: 10.1159/000158959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones CI, 3rd, Han Z, Presley T, Varadharaj S, Zweier JL, Ilangovan G, Alevriadou BR. Endothelial cell respiration is affected by oxygen tension during shear exposure: role of mitochondrial peroxynitrite. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C180–191. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00549.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J, Li Y-S, Chien S. Shear Stress–Initiated Signaling and Its Regulation of Endothelial Function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2191–2198. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryan MT, Duckles H, Feng S, Hsiao ST, Kim HR, Serbanovic-Canic J, Evans PC. Mechanoresponsive Networks Controlling Vascular Inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2199–2205. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, Kim CW, Simmons RD, Jo H. Role of flow-selective microRNAs in endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2104;34:2206–2216. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mau T, Yung R. Potential of epigenetic therapies in non-cancerous conditions. Front Genet. 2014;5:438. doi: 10.3389/fgene. eCollection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet. 2003;33:245–254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maunakea AK, Chepelev I, Zhao K. Epigenome mapping in normal and disease states. Circ Res. 2010;107:327–339. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webster ALH, Yan MS-C, Marsden PA. Epigenetics and cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JT. Epigenetic regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Science. 2012;338:1435–1439. doi: 10.1126/science.1231776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Turgeon PJ, Sukumar AN, Marsden PA. Epigenetics of cardiovascular disease: a new ‘beat’ in coronary artery disease. Med Epigenet. 2014;2:37–52. doi: 10.1159/000360766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matouk CC, Marsden PA. Epigenetic regulation of vascular gene expression. Circ Res. 2008;102:873–887. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.171025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Severin PMD, Zou X, Gaub HE, Schulten K. Cytosine methylation alters DNA mechanical properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:8740–8751. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber M, Davies JJ, Wittig D, Oakeley EJ, Haase M, Lam WL, Schubeler D. Chromosome-wide and promoter-specific analyses identify sites of differential DNA methylation in normal and transformed human cells. Nat Genet. 2005;37:853–862. doi: 10.1038/ng1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nan X, Ng H-H, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denis H, Ndlovu MN, Fuks F. Regulation of mammalian DNA methyltransferases: a route to new mechanisms. EMBO Reports. 2011;12:647–656. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Hagan HM, Wang W, Sen S, Destefano Shields C, Lee SS, Zhang YW, et al. Oxidative damage targets complexes containing DNA methyltransferases, SIRT1, and polycomb members to promoter CpG Islands. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:606–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nature Rev Genetics. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhutani N, Burns DM, Blau HM. DNA demethylation dynamics. Cell. 2011;146:866–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia D, Jurkowska RZ, Zhang X, Jeltsch A, Cheng X. Structure of DNMT3A bound to DNMT3L suggests a model for de novo DNA methylation. Nature. 2007;449:248–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell. 1999;98:285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Histone methylation: recognizing the methyl mark. Methods Enzymol. 2004;376:269–288. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)76018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang Y, Shi C, Manduchi E, Civelek M, Davies PF. MicroRNA-10a regulation of proinflammatory phenotype in athero-susceptible endothelium in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13450–13455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002120107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang Y, Davies PF. Site-Specific MicroRNA-92a Regulation of Kruppel-Like Factors 4 and 2 in Atherosusceptible Endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:979–987. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.244053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou J, Lim SH, Chiu J-J. Epigenetic regulation of vascular endothelial biology/pathobiology and response to fluid shear stress. Cell Mol Bioengineering. 2011;4:560–578. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang M. MicroRNA: a new entrance to the broad paradigm of systems molecular medicine. Physiol Genomics. 2009;38:113–115. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00080.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chuang JC, Jones PA. Epigenetics and microRNAs. Pediatric Res. 2007;61:24R–29R. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180457684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajewsky N. microRNA target predictions in animals. Nat Genet. 2006;38:S8–S13. doi: 10.1038/ng1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito Y, Liang G, Egger G, Friedman JM, Chuang JC, Coetzee GA, Jones PA. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartung CT, Michalik KM, You X, Chen W, Zeiher AM, Boon RA, Dimmeler S. Regulation and function of the laminar flow-induced non-coding RNAs in endothelial cells. Circulation. 2014;130:A18783. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi JH, Nam KH, Kim J, Baek MW, Park JE, Park HY, Kwon HJ, Kwon OS, Kim DY, Oh GT. Trichostatin A exacerbates atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2404–2409. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000184758.07257.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laukkanen MO, Kivelä A, Rissanen T, Rutanen J, Karkkainen MK, Leppanen O, Bräsen JH, Yla-Herttuala S. Adenovirus-mediated extracellular superoxide dismutase gene therapy reduces neointima formation in balloon-denuded rabbit aorta. Circulation. 2002;106:1999–2003. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031331.05368.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiltunen MO, Ylä-Herttuala S. DNA methylation, smooth muscle cells, and atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1750–1753. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000092871.30563.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lund G, Andersson L, Lauria M, Lindholm M, Fraga MF, Villar-Garea A, Ballestar E, Esteller M, Zaina S. DNA methylation polymorphisms precede any histological sign of atherosclerosis in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29147–29154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunn J, Qiu H, Kim S, Jjingo D, Hoffman R, Kim CW, Jang I, Son DJ, Kim D, Pan C, Fan Y, Jordan IK, Jo H. Flow-dependent epigenetic DNA methylation regulates gene expression and atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3187–3199. doi: 10.1172/JCI74792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Civelek M, Manduchi E, Riley R, Stoeckert CJ, Davies PF. Chronic endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-stress activates unfolded protein response (UPR) in arterial endothelium in regions of susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2009;105:453–461. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.203711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies PF, Civelek M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, redox, and a proinflammatory environment in athero-susceptible endothelium in vivo at sites of complex hemodynamic shear stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1427–1432. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou J, Li Y-S, Wang K-C, Chien S. Epigenetic mechanism in regulation of endothelial function by disturbed flow: Induction of DNA hypermethylation by DNMT1. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2014;7:218–224. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0325-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearson JC, Lemons D, McGinnis W. Modulating Hox gene functions during animal body patterning. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:893–904. doi: 10.1038/nrg1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pruett ND, Visconti RP, Jacobs DF, Scholz D, McQuinn T, Sundberg JP, Awgulewitsch A. Evidence for Hox-specified positional identities in adult vasculature. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Douville JM, Wigle JT. Regulation and function of homeodomain proteins in the embryonic and adult vascular systems. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85:55–65. doi: 10.1139/y06-091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang Y-Z, Jiménez JM, Ou K, McCormick ME, Davies PF. Differential DNA methylation of endothelial Kruppel-like Factor 4 (KLF4) promoter in response to hemodynamic disturbed flow in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res. 2014;115:32–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ling Y, Sankpal UT, Robertson AK, McNally JG, Karpova T, Robertson KD. Modification of de novo DNA methyltransferase 3a (DNMT3a) by SUMO-1 modulates its interaction with histone deacetylases (HDACs) and its capacity to repress transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:598–610. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villarreal G, Jr, Zhang Y, Larman HB, Gracia-Sancho J, Koo A, García-Cardeña G. Defining the regulation of KLF4 expression and its downstream transcriptional targets in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2010;391:984–989. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamik A, Lin Z, Kumar A, Balcells M, Sinha S, Katz J, Feinberg MW, Gerzsten RE, Edelman ER, Jain MK. Kruppel-like factor 4 regulates endothelial inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13769–13779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700078200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou G, Hamik A, Nayak L, Tian H, Shi H, Lu Y, Sharma N, Liao X, Hale A, Boerboom L, Feaver RE, Gao H, Desai A, Schmaier A, Gerson SL, et al. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4727–4731. doi: 10.1172/JCI66056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan Y, Fish JE, D’Abreo C, Lin S, Robb GB, Teichert AM, Karantzoulis-Fegaras F, Keightly A, Steer BM, Marsden PA. The cell-specific expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: a role for DNA methylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35087–35100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shirodkar AV, St Bernard R, Gavryushova A, Kop A, Knight BJ, Yan MS-C, Man H-SJ, Sud M, Hebbel RP, Oettgen P, Aird WC, Marsden PA. A mechanistic role for DNA methylation in endothelial cell-enriched gene expression: relationship with DNA replication timing. Blood. 2013;121:3531–3540. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-479170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Illi B, Nanni S, Scopece A, Farsetti A, Biglioli P, Capogrossi MC, Gaetano C. Shear stress mediated chromatin remodeling provides molecular basis for flow-dependent regulation of gene expression. Circ Res. 2003;93:155–161. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000080933.82105.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zeng L, Zhang Y, Chien S, Liu S, Shyy JY. The role of p53 deacetylation in p21Waf1 regulation by laminar flow. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24594–24599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301955200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen W, Bacanamwo M, Harrison DG. Activation of p300 histone acetyltransferase activity is an early endothelial response to laminar shear stress and is essential for stimulation of eNOS mRNA transcription. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16293–16298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801803200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zampetaki A, Zeng L, Margariti A, Xiao Q, Li H, Zhang Z, Pepe AE, Wang G, Habi O, deFalco E, Cockerill G, Mason JC, Hu Y, Xu Q. Histone deacetylase 3 is critical in endothelial survival and atherosclerosis development in response to disturbed flow. Circulation. 2010;121:132–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.890491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee D-Y, Lee CI, Lin TE, Lim SH, Zhou J, Tseng Y-C, Chien S, Chiu J-J. Role of histone deacetylases in transcription factor regulation and cell cycle modulation in endothelial cells in response to disturbed flow. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121214109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fledderus JO, Boon RA, Volger OL, Hurttila H, Ylä-Herttuala S, Pannekoek H, Levonen AL, Horrevoets AJ. KLF2 primes the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 for activation in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1339–1346. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nioi P, McMahon M, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Hayes JD. Identification of a novel Nrf2-regulated antioxidant response element (ARE) in the mouse NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 gene: Reassessment of the ARE consensus sequence. Biochem J. 2003;374:337–348. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Motta MC, Divecha N, Lemieux M, Kamel C, Chen D, Gu W, Bultsma Y, McBurney M, Guarente L. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116:551–563. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavasky R, Cohen HY, Hu LS, Cheng HL, Jedrychowski MP, Gygi SP, Sinclair DA, et al. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luo J, Nikolaev AY, Imai S, Chen D, Su F, Shiloh A, Guarente L, Gu W. Negative control of p53 by Sir2alphapromotes cell survival under stress. Cell. 2001;107:137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00524-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Z, Peng I-C, Cui X, Li Y-S, Chien S, Shyy JY-J. Shear stress, SIRT1 and vascular homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10268–10273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003833107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dekker RJ, van Soest S, Fontijn RD, Salamanca S, de Groot PG, VanBavel E, Pannekoek H, Horrevoets AJ. Prolonged fluid shear stress induces a distinct set of endothelial cell genes, most specifically lung Kruppel-like factor (KLF2) Blood. 2002;100:1689–1698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Markl M, Kilner PJ, Ebbers T. Comprehensive 4D velocity mapping of the heart and great vessels by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:7. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davies PF, Manduchi E, Stoeckert CJ, Jimenez JM, Jiang Y-Z. Emerging topic: flow-related epigenetic regulation of the atherosusceptible endothelial phenotype through DNA methylation. Vascul Pharmacol. 2014;62:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang KC, Yang YW, Liu B, Sanyal A, Corces-Zimmerman R, Chen Y, Lajoie BR, Protacio A, Flynn RA, Gupta RA, Wysocka J, Lei M, Dekker J, Helms JA, Chang HY. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]