Abstract

Background and objectives

Vital signs are usually recorded at 4–8 h intervals in hospital patients, and deterioration between measurements can have serious consequences. The primary study objective was to assess agreement between a new ultra-low power, wireless and wearable surveillance system for continuous ambulatory monitoring of vital signs and a widely used clinical vital signs monitor. The secondary objective was to examine the system's ability to automatically identify and reject invalid physiological data.

Setting

Single hospital centre.

Participants

Heart and respiratory rate were recorded over 2 h in 20 patients undergoing elective surgery and a second group of 41 patients with comorbid conditions, in the general ward.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were limits of agreement and bias. The secondary outcome measure was proportion of data rejected.

Results

The digital patch provided reliable heart rate values in the majority of patients (about 80%) with normal sinus rhythm, and in the presence of abnormal ECG recordings (excluding aperiodic arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation). The mean difference between systems was less than ±1 bpm in all patient groups studied. Although respiratory data were more frequently rejected as invalid because of the high sensitivity of impedance pneumography to motion artefacts, valid rates were reported for 50% of recordings with a mean difference of less than ±1 brpm compared with the bedside monitor. Correlation between systems was statistically significant (p<0.0001) for heart and respiratory rate, apart from respiratory rate in patients with atrial fibrillation (p=0.02).

Conclusions

Overall agreement between digital patch and clinical monitor was satisfactory, as was the efficacy of the system for automatic rejection of invalid data. Wireless monitoring technologies, such as the one tested, may offer clinical value when implemented as part of wider hospital systems that integrate and support existing clinical protocols and workflows.

Keywords: GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study presented here was conducted between 22 October 2009 and 15 July 2010, and consisted of an early evaluation of the agreement between a miniature, wireless, ‘digital patch’ system and a widely used clinical monitor for the reporting of respiration and heart rate.

The patient population comprised one group of patients who were undergoing elective surgery and one group of patients with a variety of relevant comorbid conditions.

Agreement between the two methods was generally good for the majority of situations tested. The current form of the patch was not found to be suitable for use in patients with aperiodic arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation.

Clinical and statistical review of the data confirmed that the digital patch algorithm was rejecting invalid heart rate and respiratory rate data appropriately. The device would need to be used as part of a wider system and nursing workflow.

The techniques for monitoring respiratory rate used different physical principles; neither would be regarded as a ‘gold’ standard. However, both techniques are in wide current use and so the comparison is clinically relevant.

Introduction

Patients continue to suffer unanticipated adverse events despite innovations such as early warning and scoring systems. In most hospital patients, ‘vital signs’ measurements are taken manually and recorded only intermittently, commonly at 8 h intervals, unless they have previously been identified as at particular risk of deterioration.

Therefore, deterioration can have serious consequences before it is recognised. Recent reports1 2 have highlighted that many patients still fall through this ‘safety net’, resulting in significant illness and even death, which might have been averted had the deterioration been identified earlier. This has led to a focus on early warning scoring systems designed to identify such deteriorations and deliver faster care to the patient. However, such systems are limited by the frequency with which vital signs can practicably be measured.

A landmark study from East London3 identified physiological evidence of impending deterioration some hours before collapse in a substantial proportion of patients admitted to intensive care during an emergency. Respiratory rate (RR) was shown to be particularly sensitive, but was often not accurately recorded or acted on. A further study from Portsmouth, UK, determined that initial response to deterioration was often capable of improvement.4

The issue of organising and delivering emergency responses, and their impact on improving patient outcomes remains somewhat controversial.5 However, the benefits of early identification of deterioration in patient status due, for example, to onset of infection or postoperative haemorrhage, are unarguable; the question is how to achieve this.

A recent development is the adoption of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS).6 This consists of a series of vital signs with graded scoring which sum up to form the NEWS; there is clearly an opportunity for technology to populate this score and provide alerting systems.

It is not practicable to attach all patients to monitors and indeed, the consequent reduction of mobility would itself increase the likelihood of adverse events such as blood clots and chest infections; such a solution would also be very expensive. Thus, the risk–benefit ratio would seem to favour ‘static’ monitoring for very ill patients in intensive and high-dependency units, but the issues are more finely poised for less-dependent patients in other parts of the hospital.

New wireless technology may allow increased surveillance of patients’ status without the inconvenience of physical attachment to immobile monitoring systems, allowing patients to move freely around their bed spaces, rooms and floor areas. Recent advances in miniaturisation of electronic circuits and computer technology, together with progress in battery and radio systems, has raised the possibility that an unobtrusive, low-cost surveillance system can be attached to large numbers of hospital patients. These systems can potentially capture and record data on heart rate (HR), RR and temperature (and other potentially significant biological signals). They can then transmit these data wirelessly via low-power radio to receivers in the vicinity (within 10 m) for onward transmission to central stations, to accelerate clinical response.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the performance of a wireless, digital patch system (SensiumVitals, Sensium Healthcare Ltd, London, UK) in the hospital environment, by gathering data from patients and comparing these with data synchronously obtained from patients monitored with a widely used conventional bedside clinical monitor. The precise goals were twofold: first, to assess the performance of the SensiumVitals digital patch in a clinical environment and second, to evaluate the ability of the wireless monitoring system to reject corrupted data and thus avoid/minimise the incidence of false alarms or the erroneous reporting of inappropriately reassuring data. Thus, the primary research aim was to measure agreement with outcome measures of limits of agreement and bias. The secondary aim was to evaluate rejection frequency and appropriateness.

Methods

Study procedure and participants

The study was performed in clinical areas at St Mary's Hospital, London, part of Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust. All patients gave written informed consent.

This single-centre evaluation study compared the ability of the wireless technology to acquire, transmit and log physiological variables in a clinical context. The reference clinical device was a conventional bedside clinical monitor (IntelliVue MP30, Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) currently in clinical use within St Mary's Hospital.

Patients aged 18–85 years were eligible for enrolment. Two groups were studied: group 1 consisted of 20 American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) 1–2 patients who were undergoing elective surgery; group 2 comprised 41 patients who had comorbid states which were felt to present particular challenges to the technology: low voltage or abnormal ECG morphologies, atrial fibrillation, morbid obesity (defined as a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2), and diabetes mellitus. Patients with pacemakers, implantable defibrillators or neurostimulators were excluded; patients who were eligible for group 2 were excluded from group 1.

To minimise disruption to standard workflow and practice, group 1 patients were studied in the operating room while awaiting or recovering from routine surgery; group 2 patients were studied while resting in bed in the ward or clinical areas of St Mary's Hospital.

Following informed consent, a digital patch (see below) was attached as per manufacturer's instructions to the patient's chest using two standard disposable ECG electrodes (Red-Dot2560 3M, St Paul Minn). The patient was then connected to the IntelliVue MP30 monitor via standard (three lead) ECG leads. The impedance pneumography (IP) option was then disabled and RR measured through the MP30 using capnography with standard sidestream analysis via nasal canullae (Microstream, OridionCapnography Inc, Needham, Massachusetts, USA). This was necessary because IP is an active measurement technique that relies on the injection of a small AC current via the ECG electrodes. Simultaneous use of two IP systems would cause direct interference between the two, resulting in corrupted data.

It should be noted that the two methods for measurement of RR are fundamentally different and exhibit different and uncorrelated experimental errors. For example, capnography may give a more accurate reading than IP during periods of gross patient movement, but the IP technique may provide a truer reading than capnography during periods when the patient breathes through the mouth. Thus, the major aim of the study was not to assess the accuracy of IP, which is typically validated using patient simulators or patients lying still, but to evaluate how well the two different methods compare and to assess the ability of the processing algorithms to reject invalid data and minimise false alarms under realistic hospital conditions.

Once the digital patch had been activated and was transmitting, it was registered with the wireless recorder and time-stamped data recorded on a laptop computer. Data were acquired simultaneously from the Intellivue monitor via Trendface software (Ixellence GmbH, Wildau, Germany) with the patient at rest and recorded on the same computer. Data were collected for up to 2 h provided that it was clinically convenient. The digital patch was removed for a time if the patient required surgery involving diathermy.

How the digital patch works

The SensiumVitals digital patch is a lightweight, energy-efficient, single-use device that uses the Sensium chip to monitor patients’ HR, RR and temperature in a hospital environment. It was designed as an ambulatory wireless monitoring alternative for patients throughout their stay in the general hospital ward, with no need to recharge the batteries. Several patents have been granted for the SensiumVitals technology (patent publication numbers available on request).

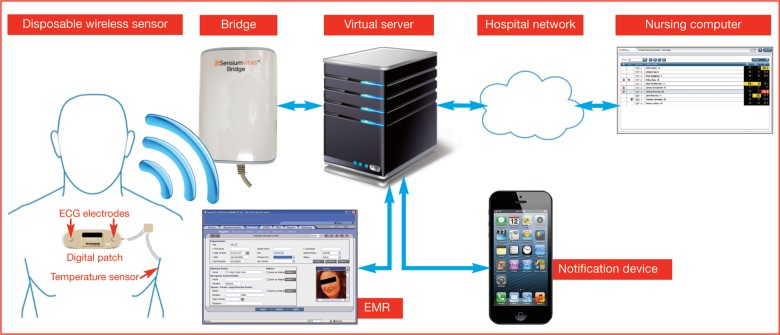

This single-lead device can be easily attached to the patient's chest by means of two self-adhesive conventional ECG electrodes (separated by approximately 10 cm), as shown in figure 1. Each patch wirelessly links and transmits the vital signs to dedicated intranet hot spots (bridges) potentially installed throughout the hospital, which ultimately convey the information to a central monitoring station/server (figure 1). Patients can be tracked and monitored unobtrusively when wearing the patch. The Sensium chip is a custom design which integrates the sensor processing and wireless communication functions into a single piece of low-cost silicon, which translates into a lightweight patch and low manufacturing cost. Therefore, the sales price is economic for ‘one per patient per stay’ use, with the patch being discarded when the patient is discharged, removing the need for cleaning and sterilisation to prevent cross-contamination.

Figure 1.

The end-to-end monitoring system for wireless continuous monitoring of vital signs.

When the patch is activated, it records respiratory (by IP) and ECG activity in a sequential and cyclical fashion. Every 2 min, the patch records a 30 s segment of ECG, followed by a 60 s segment of respiratory signal; thus the individual vital signs measurements are sequential, independent and non-continuous. Once a physiological signal is fully acquired, it is processed by its associated embedded algorithm inside the inbuilt processing unit, which results in transmission of the average values (ie, HR as beats per minute (bpm) or RR as breaths per minute (brpm)) to the nearest hot spot for onward transmission to the central monitoring system. Consequently, the algorithms on the chip are energy efficient and afford comparable accuracy to that of other types of monitoring devices. In addition, the algorithms were also designed to identify and reject physiological signals corrupted by significant sources of noise inherent to the ambulatory nature of wireless monitoring. This means that the system is embedded with a noise-detection strategy capable of automatically detecting and discarding erroneous calculations that arise from raw respiratory and ECG signals severely corrupted by electrical or motion artefacts.

At the end of each measurement period (typically 2 min cycle time), the calculated HR and RR values are transmitted from the patch to a ‘hot spot’ and then on to a storage database, providing updates to caregivers on patients’ current vital signs and notifying them if these deviate outside predefined limits. A key goal during the development of the patch was to minimise the occurrence of false alarms—that is, when a caregiver receives a notification, but the patient's vital signs remain within the specified limits. Since false alarms cause disruption to the caregiver's routine as they attend to the patient, a system with a high incidence of false alarms may actually hinder the caregiver's work rather than provide information that helps to deliver improved quality of care. False alarms due to motion artefact are minimised through the rejection of corrupted ECG and/or respiratory signals as described below.

The Sensium chip contains two algorithms for determination of HR and RR, respectively. HR is obtained using a predictive strategy that calculates this variable based on the duration of R-R intervals. This approach, based on previous developments in QRS detection,7 8 consists of two stages. First, digital signal processing techniques are applied to minimise unwanted artefacts in the signal (such as those produced by external sources as static currents, muscular electrical activity and electrode–electrolyte charge disturbances resulting from patients’ motion), and to increase the energy of the frequency components of the ECG signal linked to the QRS complexes. Second, the resultant signal is fed to the decision-making stage, which allows calculation of HR from intermittent ECG periods of 30 s in duration, based on a set of rules and empirically derived thresholds, and provided that certain internal quality assurance checks have been passed.

Part or all of each ECG segment may be severely corrupted in some cases. For example, movement of the ECG electrodes relative to the patient's skin may generate transient voltages, which can be much larger than the detected ECG waveform. Similar distortion can also arise from static electricity coupling on to the patient's skin. This issue has been addressed in the algorithm by implementation of additional rules and a number of statistical estimators to verify the signal's integrity. Thus, segments of the ECG waveform deemed to be corrupted—as fluctuations in periodicity and amplitude of the ECG segment do not meet preset experimental thresholds—are automatically excluded from calculation of HR. In addition, the entire segment is excluded and the system reports an ‘invalid HR’ if the majority of the ECG (ie, about 85% of the data segment) is corrupted.

The algorithm that quantifies RR also comprises two stages: a preprocessing stage that identifies and filters interference, and a postprocessing stage responsible for detection of valid breathing cycles and calculation of RR. The preprocessing stage includes a novel filter that dynamically tunes its rejection frequency in accordance with the HR obtained during the current monitoring cycle, thereby attenuating any heart contaminants produced by dynamic changes in impedance due to inflow and outflow of blood to the heart and great vessels.

A fundamental limitation of IP is that the primary respiratory signal is easily corrupted by noise produced by different electrical and mechanical sources (motion artefact). To attenuate this type of noise, the algorithm first relies on autocorrelation (cross-correlation of the detrended signal with itself)—enhancing signal periodicities while suppressing aperiodic interference. The resultant output is further analysed by a peak detection and signal validity routine whose rules are heuristically defined in accordance with the expected characteristics of the respiratory signal and thus, allows evaluation of aspects such as signal periodicity and the number of respiration events detected from the autocorrelation periodogram. As with the ECG, respiratory signals that are severely corrupted by noise (variability in the respiration peak to peak intervals of more than 25%) or lack appropriate respiration information (eg, when the patient talks, swallows or coughs) are automatically discarded by the system and a code indicating an invalid RR is transmitted to the base station, when no periodic information can be extracted from the signal. Otherwise, a valid RR is calculated and transmitted. This ensures that only clinically relevant RR values are transmitted to the caregiver, thus minimising the occurrence of false alarms.

Data handling and statistical analysis

Raw signal data were collected from each patient, using a personal computer running data-acquisition software developed by Sensium Healthcare Limited (SHC). The recorded data sets were then processed using a test-bench interface also developed by SHC using MATLAB (MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA).

As discussed earlier, the digital patch algorithms were specifically designed to automatically exclude data that do not meet prespecified criteria. Data that failed to meet these a priori quality standards were rejected; all other data points were included in the analysis. Individual patient ‘raw’ data were reviewed in MATLAB by three of the investigators (MH-S, S-SA and SJB) to determine whether data had been accepted or rejected appropriately by the algorithm. It is important to emphasise that the researchers were blinded from the outputs of the automatic discrimination rules as they ran inside the patch at the moment of acquiring and processing the raw data.

Subsequently, spreadsheets were prepared containing the HR and RR values from the digital patch together with the corresponding values from the MP30 monitor. The data were compared using simple Pearson's correlation, and the method of Bland and Altman.9 This allowed for comparative estimates of bias (mean difference between values obtained by the two different methods), and limits of agreement (±1.96×SD of the mean difference between the two methods).

Estimates of data availability were also produced. These were defined as actual data points reported as a percentage of total possible data points during the recording period. This variable was intended to give a guide to the utility of IP as a means of estimating RR in non-sedated patients as data rejection was anticipated due to motion artefact, intermittent loss of electrode contact or patch malfunction. Similar data were calculated for HR; this part of the system was anticipated to be more robust.

Results

Patient enrolment occurred between 22 October 2009 and 15 July 2010. Group 1 consisted of 20 patients who underwent elective surgery at St Mary's Hospital, while group 2 comprised 41 patients who were recruited from the clinic or ward areas of the hospital. Patients were monitored for approximately 2 h. Bland and Altman plots for the data from both groups are presented in figures 2–4 and table 1. Individual recordings are presented in the online supplementary appendix.

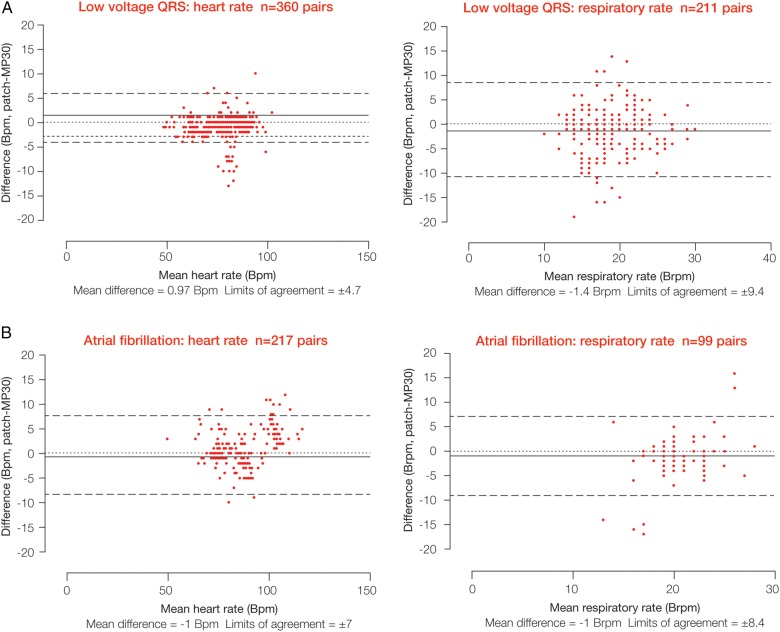

Figure 2.

Comparison of heart and respiratory rate data between the wireless, digital patch monitoring system and the reference bedside monitor during a 2 h monitoring period in patients who had undergone elective surgery (group 1 patients).

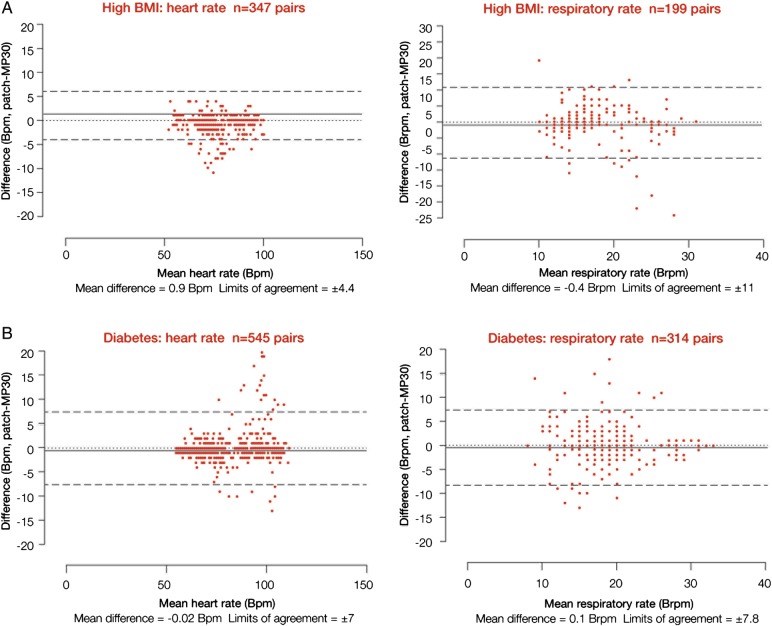

Figure 3.

Comparison of heart and respiratory rate data between the wireless, digital patch monitoring system and the reference bedside monitor during a 2 h monitoring period in patients with low voltage/variable QRS morphology (A) and patients with atrial fibrillation (B).

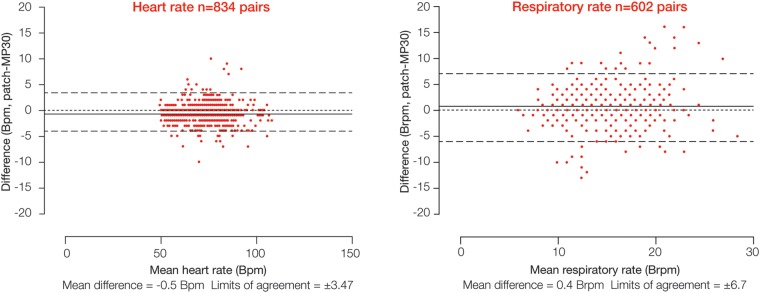

Figure 4.

Comparison of heart and respiratory rate data between the wireless, digital patch monitoring system and the reference bedside monitor during a 2 h monitoring period in patients with a high body mass index (>30 kg/m2; A) and patients with diabetes (B).

Table 1.

Proportions of data from the wireless digital patch during continuous monitoring over a 2 h period; these data largely reflect the patch algorithm rejecting data that did not pass the internal quality assurance step

| Group | Heart rate availability (%) | Respiratory rate availability (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Operative | 98.6 | 64 |

| 2 | Low voltage QRS | 92 | 56 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 45 | 20 | |

| High body mass index | 80 | 54 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 77 | 45 |

In general, good agreement was seen between measurements recorded with the wireless, digital patch system and those obtained with the reference bedside monitor.

Group 1 patients

Twenty patients were recruited (13 male, mean (SD) age 49 (±16) years). Bland and Altman plots (figure 2) showed a mean difference in HR of −0.5 bpm between the digital patch and the bedside monitor, with limits of agreement of ±3.47 bpm; 98.6% of potentially available data were actually available (table 1). For RR, the mean difference was 0.4 brpm, with limits of agreement of ±6.7 brpm (figure 2); 64% of potentially available data were actually available (table 1). Correlation coefficients were 0.99 (p<0.0001) for HR and 0.67 (p<0.0001) for RR. The total numbers of data points corresponding to HR and RR were 834 and 602, respectively.

Group 2 patients: cardiovascular disorders

Low voltage/variable QRS morphology (n=9, 7 male, mean (SD) age 62 (±12) years)

The Bland and Altman plots are shown in figure 3A and the proportion of data in table 1. The mean difference in HR between the digital patch and the bedside monitor was 0.97 bpm, with limits of agreement of ±4.7 bpm; 92% of potentially available data were actually available. The mean difference in RR was −1.4 brpm, with limits of agreement of ±9.4 brpm; 56% of data were actually available. The correlation coefficients were 0.98 (p<0.0001) for HR and 0.39 (p<0.0001) for RR. In total, 360 and 211 data points, respectively, corresponded to available HR and RR values for this group.

Atrial fibrillation (n=10, 6 male, mean (SD) age 78 (±6) years)

Results are shown in figure 3B and table 1. Very limited usable data were obtained from this group—that is, only 217 pairs were available for HR and 99 for RR. For HR, the mean difference between monitoring systems was −1 bpm, with limits of agreement of ±7 bpm; 45% of potentially available data were actually available. For RR, the mean difference was −1 brpm, with limits of agreement of ±8.4 brpm; 20% of the data were actually available. The correlation coefficients were 0.96 (p<0.0001) for HR and 0.22 (p=0.02) for RR.

Group 2 patients: metabolic disorders

High BMI (n=10, 4 male mean (SD) age 51 (±11) years)

Bland and Altman plots are shown in figure 4A and data proportions in table 1. The mean difference in HR between monitoring systems was 0.9 bpm, with limits of agreement of ±4.4 bpm; 80% of potentially available data were actually available. For RR, the mean difference was −0.4 brpm, with limits of agreement of ±11 brpm; 54% of data were available. The correlation coefficients were 0.98 (p<0.0001) for HR and 0.48 (p<0.0001) for RR. In total, 347 and 199 data points, respectively, corresponded to available HR and RR values for this group.

Diabetes (n=11, 9 male, mean (SD) age 51 (±11) years)

Results are shown in figure 4B and table 1. For HR, the mean difference between monitoring systems was −0.02 bpm, with limits of agreement of ±7 bpm; 77% of data were available. The mean difference in RR was 0.1 brpm, with limits of agreement of ±7.8 brpm; 45% of data were available. The correlation coefficients were 0.97 (p<0.0001) for HR and 0.64 (p<0.0001) for RR. The numbers of data points available for this group were 545 and 314 for HR and RR, respectively.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this was, at the time, the first trial of a system with miniaturised wireless monitoring in a hospital clinical environment—using equipment intended to monitor large numbers of patients wirelessly.

Our study confirmed that the SensiumVitals digital patch provides reliable information on HR from patients with normal sinus rhythm. Valid HR data were reported for the majority of the time (typically >80%), even in the presence of abnormal QRS morphology. When patients with atrial fibrillation were excluded, HR data were reported with a mean difference of less than 1 bpm compared with the IntelliVue monitor.

Although RR data were rejected as invalid more frequently than HR data due to the nature of the IP technique, valid data were typically reported for 50% of the time, providing a useful information update rate for the caregiver. Accuracy was good when valid RR data were reported, with a mean difference of less than 1 brpm compared with the bedside monitor. The correlation coefficients were high for HR data (≥0.96) and lower values were reported for RR, as would be expected with the use of these two different measurement methods. However, the correlation between methods was statistically significant (p<0.0001), apart from patients with atrial fibrillation.

In patients with atrial fibrillation, a large percentage of the data were rejected as invalid for HR and RR. Differences of up to ±6 were previously obtained when the data were tested with those collected from a patient simulator (SimMan, Laerdal Medical Ltd, Kent, UK; data not shown) during an earlier pilot evaluation. Since this arrhythmia is characterised by aperiodic R-R intervals and irregular ECG morphology (eg, the absence of P waves), it is entirely expected that the algorithm may reject HR data. As previously discussed, it should be borne in mind that part of the algorithm's philosophy is to reject such irregular waveforms and report them as ‘invalid’ to avoid false alarms due to motion artefact or the transmission of data with low certainty of accuracy. Transmission of falsely reassuring data would be potentially hazardous.

When ECG data are rejected and no valid HR value is generated, the ‘self-tunable’ filter in the RR algorithm cannot be correctly centred. Consequently, the filter may attenuate the valid respiration waveform, in which case an invalid signal may also be reported for RR, explaining why respiration data for atrial fibrillation patients are reported as invalid for a significant percentage of the time (80%). These findings led to the conclusion that the digital patch, in its current form, is unsuitable for use in patients with atrial fibrillation or other aperiodic arrhythmias.

Overall, RR was reported less frequently than HR, due either to lack of regular HR data or to gross signal corruption due to motion artefact, an inherent issue with IP-based methodologies.

From a clinical perspective, it is vital that monitoring systems do not deliver falsely reassuring data, since this may potentially prevent deteriorating patients from receiving the attention they need. The modest level of data availability under some circumstances, particularly atrial fibrillation, highlights two key points. First, the digital patch algorithm is rejecting data appropriately. Second, achievement of miniaturised wireless monitoring presents real engineering challenges, particularly in ambulatory patients.

However, the data acquisition technologies, as evaluated in this study, form only one part of a clinical system. The static network and processing components of the system, plus the clinical protocols and routines, must be designed to take account of the limitations of what we can currently achieve with miniaturised vital signs monitoring devices. With the digital patch, the use of intelligent algorithms to reject corrupted data is augmented by automated notifications to advise the caregiver that valid data have not been received from a patient for a defined period of time and that clinical review may be required. Thus, the delivery of inaccurate, potentially falsely reassuring data or the occurrence of false alarms is minimised, while ensuring that surveillance of patient status is maintained.

Other investigators have also demonstrated the potential of wireless technology for remote surveillance or management. Some have used implantable devices: for example, the study of Abraham et al10 monitored pulmonary artery pressure intermittently in heart failure; others have used equipment implanted for other reasons.11 Wireless technology platforms are being applied to increasing numbers of clinical situations: interesting examples have been described for diabetes management,12 remote monitoring of home ventilatory support,13 and investigation of gastrointestinal disease.14 Preliminary studies using the Vitalsens device (VS100: Intelesens Ltd, Northern Ireland), which can record and transmit similar parameters to the SensiumVitals digital patch, have been promising and have confirmed proof of general concept. The former device, however, is philosophically very different—being larger and reusable in design—in contrast to the single-use miniaturised disposable SensiumVitals.15–17

The objectives of this study were met, as agreement between methods and rejection of corrupted data were demonstrated for the miniaturised wireless digital patch under the majority of circumstances tested.

A limitation of this study is related to the short duration of the data collection intervals and the number of participants available, given the conditions of the workflow in these critical settings. However, it should be borne in mind that this was a preliminary feasibility study and therefore, a further clinical evaluation with a significant sample of participants in the general ward must be carried out to reaffirm the outcomes of this investigation. In addition, in this preliminary study, patients were monitored at rest and thus, we can make no assumptions concerning performance with patients moving around in a truly ambulatory context.

Wireless technologies for measurement of vital signs, such as the one used in this study, have now developed to the point where they have the potential to make a substantial contribution to patient safety. Evaluation of end-to-end system performance within the hospital environment will provide further information on the clinical value and acceptance of the wireless monitoring system in routine practice as part of a wider system to augment and support existing clinical protocols and workflows.

Acknowledgments

KA acknowledges research funding from NIHR, Royal College of Surgeons England, and the Urology Foundation.

Footnotes

Contributors: SJB was involved in the planning (clinical trial design and ethics submission), conduct (Chief Investigator) and reporting of the study (drafting/editing of results). CT was involved in the invention of the device and the planning of the study. TM and RW assisted in the planning of the study (submission of approvals documentation) and in its conduct (provision of equipment and technical support). FZ was responsible for the conduct of the study (research nurse). KA was involved in the reporting of the study (analysis of clinical data). MH-S, S-SA and AB were involved in the reporting of the study (drafting/editing of the paper). All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by CareFusion Corporation, Torrey View Court, San Diego. SJB is supported by the NIHR Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre based at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust and Imperial College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: MH-S, S-SA, TM, RW, and AB were at the time of the study, full time employees of Sensium Healthcare Limited (formerly Toumaz UK Ltd). SJB was Chief Investigator and received grant support from CareFusion to conduct the study. CT invented the SensiumVitals digital patch. He is an employee of Imperial College London and non-Executive Director of Sensium Healthcare Limited (formerly Toumaz UK Ltd).

Ethics approval: Research ethics approval was obtained (NRES reference: 09-H0712-63) and the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency issued a certificate of non-objection.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Individual patient recordings are available as an electronic supplement.

References

- 1.National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, 2005. An acute problem. http://www.ncepod.org.uk/2005aap.htm (accessed Mar 2015).

- 2.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007. Acutely ill patients in hospital: recognition of and response to acute illness in adults in hospital. http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG50/NiceGuidance/pdf (accessed Mar 2015).

- 3.Goldhill DR, White SA, Sumner A. Physiological values and procedures in the 24 hours before ICU admission from the wards. Anaesthesia 1999;54:529–34. 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00837.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McQuillan P, Pilkington S, Allan A et al. . Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. BMJ 1998;316:1853–8. 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao H, McDonnell A, Harrison DA et al. . Systematic review and evaluation of physiological track and trigger warning systems for identifying at-risk patients on the ward. Intensive Care Med 2007;33:667–79. 10.1007/s00134-007-0532-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS): standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Report of a working party London: RCP, 2012. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/resources/national-early-warning-score-news (accessed Mar 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan J, Tomkins WJ. A real-time QRS deterioration algorithm. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1985;32:230–6 10.1109/TBME.1985.325532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton P, Tompkins W. Quantitative investigation of QRS detection rules using the MIT/BIH arrhythmia database. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1986;33:1157–65 10.1109/TBME.1986.325695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC et al. , the CHAMPION Trial Study Group. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:658–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60101-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crossley GH, Boyle A, Vitense H et al. , the CONNECT Investigators. The CONNECT (clinical evaluation of remote notification to reduce time to clinical decision) trial: the value of wireless remote monitoring with automatic clinician alerts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1181–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seto E, Istepanian RS, Cafazzo JA et al. . UK and Canadian perspectives of the effectiveness of mobile diabetes management systems. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2009;2009:6584–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Almeida JP, Pinto AC, Pereira J et al. . Implementation of a wireless device for real-time telemedical assistance of home-ventilated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a feasibility study. Telemed J E Health 2010;16:883–8. 10.1089/tmj.2010.0042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarosiek I, Selover KH, Katz LA et al. . The assessment of regional gut transit times in healthy controls and patients with gastroparesis using wireless motility technology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:313–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper R, Donnelly N, McCullough I et al. . Evaluation of a CE approved ambulatory patient monitoring device in a general medical ward. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2010;2010:94–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnelly N, Harper R, McCAnderson J et al. . Development of a ubiquitous clinical monitoring solution to improve patient safety and outcomes. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2012;2012:6068–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly N, Hunniford T, Harper R et al. . Demonstrating the accuracy of an in-hospital ambulatory patient monitoring solution in measuring respiratory rate. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2013;2013:6711–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]