ABSTRACT

Replication and transcription activator (RTA) of gammaherpesvirus is an immediate early gene product and regulates the expression of many downstream viral lytic genes. ORF48 is also conserved among gammaherpesviruses; however, its expression regulation and function remained largely unknown. In this study, we characterized the transcription unit of ORF48 from murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) and analyzed its transcriptional regulation. We showed that RTA activates the ORF48 promoter via an RTA-responsive element (48pRRE). RTA binds to 48pRRE directly in vitro and also associates with ORF48 promoter in vivo. Mutagenesis of 48pRRE in the context of the viral genome demonstrated that the expression of ORF48 is activated by RTA through 48pRRE during de novo infection. Through site-specific mutagenesis, we generated an ORF48-null virus and examined the function of ORF48 in vitro and in vivo. The ORF48-null mutation remarkably reduced the viral replication efficiency in cell culture. Moreover, through intranasal or intraperitoneal infection of laboratory mice, we showed that ORF48 is important for viral lytic replication in the lung and establishment of latency in the spleen, as well as viral reactivation from latency. Collectively, our study identified ORF48 as an RTA-responsive gene and showed that ORF48 is important for MHV-68 replication both in vitro and in vivo.

IMPORTANCE The replication and transcription activator (RTA), conserved among gammaherpesviruses, serves as a molecular switch for the virus life cycle. It works as a transcriptional regulator to activate the expression of many viral lytic genes. However, only a limited number of such downstream genes have been uncovered for MHV-68. In this study, we identified ORF48 as an RTA-responsive gene of MHV-68 and mapped the cis element involved. By constructing a mutant virus that is deficient in ORF48 expression and through infection of laboratory mice, we showed that ORF48 plays important roles in different stages of viral infection in vivo. Our study provides insights into the transcriptional regulation and protein function of MHV-68, a desired model for studying gammaherpesviruses.

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), is a member of the gamma subfamily of the Herpesviridae and is etiologically associated with several human malignances, such as Kaposi's sarcoma, multicentric Castleman's disease, and primary effusion lymphoma (1). Like all other herpesviruses, KSHV exhibits two distinct life cycles: latency and lytic replication. During the latent stage, the viral genome resides in the nucleus as a circular episome and expresses only a subset of viral genes, with no production of infectious viral particles (2–4). In contrast, during lytic replication, most, if not all viral genes, classified as immediate early, early, and late, are expressed in a highly regulated cascade manner, resulting in the release of progeny viruses for subsequent infection of naive cells and transmission to new hosts. Except in some types of multicentric Castleman's disease, viral latency is the predominant form of infection in most KSHV-associated diseases and, hence, is considered to directly contribute to KSHV-related tumorigenesis. Even though viral lytic replication is found only in a small fraction of infected cells, it is a critical pathogenic step in the development of KSHV-related diseases. Lytic replication plays important roles in enhancing the latently infected cells in a paracrine fashion and also in replenishing the pool of latently infected cells by continuously infecting naive cells (5, 6).

KSHV, with a genome of approximately 165 kb, encodes more than 80 proteins (7, 8) although the function of many viral proteins remains mysterious. Until recently, studies on the function of KSHV lytic proteins had been severely hampered due to the lack of an effective de novo lytic infection system and, more importantly, the lack of suitable small-animal models. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) is a member of the gammaherpesvirus subfamily, and it is genetically and biologically closely related to KSHV (9). MHV-68 replicates in permissive cell lines in a robust manner, and its bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) system facilitates genetic manipulation and subsequent functional assays. Moreover, as a natural pathogen to small rodents, MHV-68 can establish transient lytic infection in the lung, followed by latent infection in B lymphocytes and macrophages in the spleen of laboratory mice (10, 11) after infection via the respiratory route. Consequently, MHV-68 has served as a model for studying its two human counterparts, KSHV and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), in recent years.

The replication and transcription activator (RTA), mainly encoded by ORF50, is conserved among gammaherpesviruses (12–15). As an immediate early gene product, RTA serves as a molecular switch in the life cycle of KSHV and MHV-68 by initiating lytic replication and activating downstream gene transcription (15–19). In order to better understand the cascade control of gammaherpesvirus lytic gene expression, it is critical to identify viral genes activated by RTA and to investigate the mechanisms by which RTA regulates the expression of these viral genes. In KSHV, a number of genes have been reported to be activated by RTA (19–29), while in MHV-68, only three RTA-responsive genes have been identified, which are v-cyclin, ORF18, and ORF57 (30–32).

According to sequence alignment, ORF48 is conserved in all gammaherpesviruses. In KSHV, ORF48 was reported to be an immediate early gene with unknown function (33); in MHV-68, it was reported to be a tegument-associated protein (34) but was not essential for viral lytic replication or latency establishment, and its function was unclear (35, 36). However, rather than being based on site-specific mutagenesis, these results were mainly based on studies using deletion of large fragments (36) or insertions (35). Because this genomic region is very compact, such large-scale genetic manipulations might affect the expression of several neighboring genes and thus alter the viral phenotype, masking the true function of ORF48.

In this study, we investigated the transcriptional regulation and in vivo function of ORF48. We report here that ORF48 is a viral early gene product and can be activated by RTA. We further identified an RTA-responsive element (RRE) in the ORF48 promoter (designated 48pRRE) through reporter assays, showed direct binding of RTA to 48pRRE in vitro and in vivo, and validated it during MHV-68 de novo lytic infection. By constructing an ORF48-null virus through site-specific mutagenesis, we showed that ORF48 is important for viral lytic replication in the lung, establishment of latency in the spleen, and viral reactivation from latency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and plaque assays.

All cells were cultured at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. 293T cells, BHK-21 cells, and Vero cells were grown and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) and antibiotics (50 U of penicillin and 50 μg of streptomycin per ml). MHV-68 was originally obtained from Ren Sun (University of California, Los Angeles) and was propagated by infecting BHK-21 or NIH 3T3 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.05 PFU/cell. At 5 days postinfection (p.i.), the supernatant was harvested and cleared of large cellular debris by centrifugation (1,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C). To infect BHK-21 cells, the viral inoculum in DMEM was incubated with cells for 1 h with occasional swirling. The inoculum was removed and replaced with fresh DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum. For experiments involving cycloheximide (CHX; Sigma) or phosphonoacetic acid (PAA; Sigma), cells were treated at a concentration of 200 μg/ml during and after viral inoculation until they were harvested. Viral titers were measured by a standard plaque assay as descried previously (37). Briefly, monolayers of BHK-21 cells were infected with virus for 1 h and overlaid with 1% methylcellulose (Sigma) for 5 days. Cells were fixed and stained with 0.2% crystal violet (in 20% ethanol), and plaques were then counted to determine the titer.

Plasmid construction.

Plasmid p48p1 was constructed by amplifying through PCR a 1-kb fragment upstream of the ORF48 initiation codon (GenBank accession number NC_001826.2, nucleotides [nt] 66584 to 67626) using primers ORF48pF1 (5′-CAGACGCGTTATCCTTCTCTGGAAAGCGTGG-3′) and ORF48pR (5′-CAGAGATCTTATCCCACAATGTGCTGCAGTC-3′) and cloning into the BglII and MluI sites of pGL3-basic (Promega). The 5′ end deletion mutants of p48p1 (p48p2 to p48p5) were generated by PCR through a similar strategy. The site-directed mutagenesis mutants based on p48p2 were generated via a PCR-based mutagenesis system. All deletion and site-directed mutations were confirmed by sequencing.

To construct pCMVHA-mRTA (where mRTA is MHV-68-encoded RTA), the rta genomic sequence was amplified by PCR with the primers RTAF (5′-GCGAATTCCGATGGCCTCTGACTCG-3′) and RTAR (5′-CAGGGTACCTTTGGCACCGTTTATGACT-3′). The PCR product was subjected to EcoR I and KpnI digestion and then cloned into pCMV-HA (Clontech) vector.

RNA extraction, Northern blotting, and reverse transcription.

Total RNA was extracted from BHK-21 cells infected with MHV-68 at an MOI of 5 at different time points using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). A 10-μg portion of each RNA sample was denatured and then separated on a 1% agarose gel containing 2% formaldehyde in MOPS buffer (20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS], 5 mM sodium acetate, and 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.0). An RL6000 RNA ladder (TaKaRa) was loaded onto the gel as a size standard. RNAs were transferred to a charged nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The membrane was UV cross-linked, prehybridized, and hybridized at 65°C in formamide prehybridization/hybridization solution (50% formamide, 5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 5× Denhardt's solution, 1% SDS) with a biotin-labeled double-stranded DNA probe.

For reverse transcription, 2 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed by Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (M-MLV) using oligo(dT)15 primer. ORF48 and β-actin coding sequences were amplified by PCR. PCR products were resolved by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

The labeling reactions for double-stranded DNA probes were performed in a 20-μl reaction mixture (0.5 mM [each] dATP, dGTP, and dCTP, 0.25 mM dTTP, 0.25 mM biotin-dUTP, 400 ng of template DNA, 5 pmol of primer, and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase). PCR was initiated with a denaturing step of 4 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of sequential steps of 1 min at 94°C, 30s at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C. Finally, the reaction was extended for 5 min at 72°C.

RACE.

Total RNA was extracted from BHK-21 cells 12 h after infection with MHV-68 (MOI of 1) using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The 5′ and 3′ ends of the ORF48 mRNA were identified using a FirstChoice RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-RACE) kit (Ambion). Briefly, for the 5′ end, total RNA was treated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIP) to remove free 5′ phosphates. The cap structure found on intact 5′ ends of mRNA was not affected by CIP. The RNA was then treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) to remove the cap structure from full-length mRNA, leaving a 5′ monophosphate. A 45-base RNA adapter oligonucleotide was ligated to the RNA population using T4 RNA ligase. A random-primed reverse transcription reaction and subsequent nested PCR with specific primer located at nt 66362 on the MHV-68 genome were then carried out. For the 3′ end, first-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA, using the supplied 3′ RACE adapter. The cDNA was then subjected to PCR using a 3′ RACE primer that is complementary to the anchored adapter with another specific primer located at nt 65629 on the MHV-68 genome.

Antibodies, Western blotting, and indirect immunofluorescence assay.

Cells were lysed in 1× protein loading buffer, heated at 95°C, and run on SDS-PAGE gels for Western blotting. Proteins were then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore), incubated sequentially with primary antibody and secondary antibody, and detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Millipore). For indirect immunofluorescence assay, Vero cells were infected with recombinant MHV-68 virus (r68) at an MOI of 0.5 and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde after 12 h of infection. The fixed cells were permeabilized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.2% Triton X-100, incubated sequentially with mouse monoclonal anti-HA (1:500) antibody as the primary antibody and with secondary antibody conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (1:100) or indodicarbocyanine (Cy5), stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 μg/ml), and examined using a confocal microscope (Olympus).

Dual-luciferase reporter assay.

A dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) was used to test promoter activity. Fifty nanograms of reporter plasmids was individually transfected into 293T cells in a 24-well plate with either 900 ng of pCMVHA-mRTA plasmid or empty pCMV-HA vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Ten nanograms of pRL-CMV vector, which contains the coding sequence for Renilla luciferase under the control of a constitutively active CMV promoter, was included in each transfection and served as an internal control for transfection efficiency. 293T cells were collected at 48 h posttransfection. Cells were washed with 1× PBS and incubated with 100 μl of 1× passive lysis buffer (PLB) provided by the manufacturer. Lysates were centrifuged at top speed in a microcentrifuge for 5 min, and supernatants were assayed for reporter activities according to the manufacturer's instructions.

EMSA.

An electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed according to a previously described method (32, 38, 39). Briefly, oligonucleotides were labeled with a biotin 3′ end DNA labeling kit (Pierce) and then incubated with nuclear extract from pFLAGCMV2-mRTA-transfected 293T cells. For a supershift assay, 1 μl of anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) was added into the binding reaction mixture. For a competition assay, a 200-fold excess amount of unlabeled RREA oligonucleotide was added. After incubation, oligonucleotides were resolved on native polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto Hybond-N+ membrane and immobilized by UV cross-linking. Biotin-labeled oligonucleotides were detected using a Phototope-Star chemiluminescence detection kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (New England BioLabs).

ChIP assay.

Two million 293T cells were transfected with 1 μg of p48p2 or p48p2-mDI (where mDI indicates a mutation in ORF48 promoter sites D and I) and 9 μg of pFLAGCMV2-mRTA (or empty vector pFLAGCMV2). Two days later, cells were washed twice with PBS and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. After three more washes with PBS, cells were lysed in 450 μl of SDS lysis buffer, and DNA was fragmented by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min to remove cellular debris. For chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), 200 μl of supernatant was diluted in 1,800 μl of ChIP dilution buffer and further incubated with 10 μl of anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated beads (Sigma). Beads were pelleted at low speed, sequentially washed with low-salt wash buffer, high-salt wash buffer, LiCl buffer, and Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer (pH 8.0). DNA-protein complexes were eluted from the beads by incubation in 250 μl of elution buffer. NaCl was added to the elution buffer at a final concentration of 100 mM, and DNA-protein cross-links were reversed by incubation at 65°C for 4 h. Following treatment with proteinase K, DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. DNA was quantified by real-time PCR with the following primers: ORF48p-F, 5′-GCA GAA ATT CCC TCG TAG TGC-3′; ORF48p2-R, 5′-TGG AAA TCT GGT AGC TCC TCC TA-3′; actin-F, 5′-AGT TGC GTT ACA CCC TTT CTT G-3′; actin-R, 5′-CAC CTT CAC CGT TCC AGT TTT-3′.

Generation of recombinant MHV-68.

Based on an MHV-68 BAC, a series of recombinant constructs, including BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA, BAC-mDI, BAC-48S, and BAC-48S.R (a revertant of BAC-48S), were generated by allelic exchange in Escherichia coli, using procedures described previously (40, 41). Briefly, a fragment spanning the target region and the flanking sequences was cloned into ampicillin (Amp)-resistant plasmid pGS284, harbored in E. coli GS111, and used as the donor strain for allelic exchange with the recipient strain GS500 (recA) harboring chloramphenicol (Cam)-resistant MHV-68 (BAC-7). For BAC-48S, nucleotides GAG were also inserted downstream of the stop codon sequence to generate an XhoI site and facilitate screening of the clones. The restriction patterns of BAC constructs were verified by comparison with those of BAC-7. Fragments with mutation sites were PCR amplified from BAC plasmids and sequenced to confirm that all mutations are correct.

To propagate the mutant MHV-68 viruses, the desired recombinant BACs were transfected into BHK-21 cells, and supernatant from each transfection was collected when cells showed complete cytopathic effect (CPE). Virus titer was determined by plaque assay. To remove the vector sequence from MHV-68 BAC viruses, 293T cells were cotransfected with MHV-68 BAC DNA and a plasmid expressing Cre recombinase. Three days posttransfection, a single viral clone was isolated by limiting dilution and propagated for further studies.

DNA extraction and real-time PCR.

To measure the copy numbers of viral genomes, total DNA was extracted from splenocytes by phenol-chloroform extraction. DNA was amplified by TransStart Eco Green qPCR SuperMix (Transgen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with primers located in the ORF65 region on the MHV-68 genome (Q-ORF65F, 5′-GTCAGGGCCCAGTCCGTA, and Q-ORF65R, 5′-TGGCCCTCTACCTTCTGTTGA). Amplification and detection were performed using a Bio-Rad MyIQ real-time PCR detection system. For each reaction, 100 ng of DNA was analyzed in triplicates, and a standard curve was obtained by measuring 5.12 × 10−6 ng to 10 ng of MHV-68 BAC spiked into 100 ng of splenocyte DNA from an uninfected mouse.

Mouse administration and in vivo infection.

Maintenance of mice and experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Welfare and Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All procedures were performed under pentobarbital sodium anesthesia to minimize the suffering of mice. Four- to six-week-old, specific-pathogen free (SPF) female BALB/c mice were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology. For in vivo infection, r68, 48S, and 48S.R viruses were amplified in NIH 3T3 cells and purified by centrifugation to remove cellular debris. The mice were anesthetized intraperitoneally (i.p.) with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg body weight) and then either inoculated intranasally (i.n.) with 15 μl of viral stock containing 500 or 5 × 104 PFU of recombinant MHV-68 viruses or infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 500 PFU of recombinant MHV-68 viruses in 500 μl of DMEM. The viral titers in the lung and viral reactivation from splenocytes were examined as described previously (42, 43). Briefly, the lung was homogenized in 1 ml of DMEM, and the virus titers were determined by three independent plaque assays. For infectious center assays, serial dilutions of splenocytes were laid onto BHK-21 cells, and after 6 days BHK-21 cells were fixed to determine the numbers of plaques. The plaques referred to as infectious centers arise as a result of the virus reactivation from latency. For ex vivo limiting dilution assays, BHK-21 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at 103 cells/well. Twofold serial dilutions of splenocytes starting at 106 cells per well were plated onto BHK-21 cells. After 7 days, each well was scored for cytopathic effects, and the percentage of cytopathic effects per 24 wells was determined for each dilution.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The MHV-68 ORF48 is an early gene.

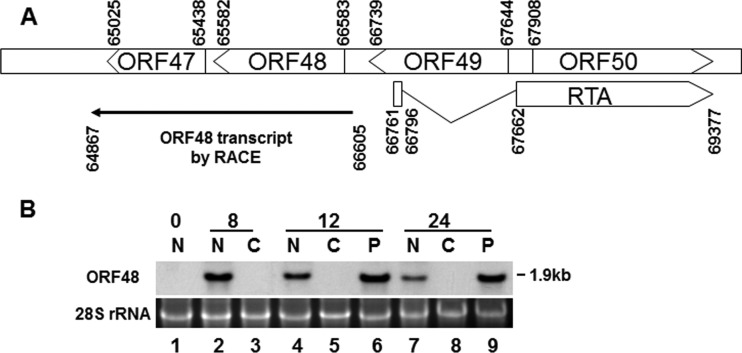

The ORF48 gene is located in the middle of the MHV-68 genome, but its expression has not been thoroughly analyzed. We first sought to characterize the transcription unit of ORF48 by identifying the termini of ORF48 transcripts. We infected BHK-21 cells, which are permissive for robust MHV-68 lytic replication, for 12 h and isolated total RNA to perform both 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE). As shown in Fig. 1A, the ORF48 transcript initiates at nt 66605 (GenBank accession number NC_001826.2) and terminates at nt 64847, and thus the calculated size of the ORF48 transcript would be 1.9 kb. We then examined transcriptional kinetics of ORF48 during MHV-68 de novo infection. We infected cells with MHV-68 in the absence or presence of either cycloheximide (CHX) or phosphonoacetic acid (PAA), collected cells at the time points indicated on Fig. 1B, and analyzed ORF48 expression by Northern blotting. The size of the detected ORF48 transcript is 1.9 kb (Fig. 1B), consistent with what is predicted from the RACE data. Moreover, expression of the ORF48 mRNA was resistant to inhibition by PAA (Fig. 1B, lanes 6 and 9) but completely vanished in the presence of CHX (Fig. 1B, lanes 3, 5, and 8), indicating that ORF48 is a viral early gene. This result was consistent with the findings from a previous genome-wide transcription profiling work (44).

FIG 1.

Characterization of the MHV-68 ORF48. (A) Schematic diagram of the locus containing RTA and ORF48 on the MHV-68 genome. Transcription initiation and termination sites of the ORF48 transcripts as mapped by 5′ and 3′ RACE assays are also shown. A total of six clones from 5′ RACE were sequenced; the transcription initiation sites were mapped to nt 66605 in four clones and to nt 66603 in two other clones. A total of six clones from 3′ RACE were sequenced; the transcription termination sites were mapped to nt 64867 in five clones and to nt 64869 in one additional clone. (B) MHV-68 ORF48 is expressed as an early gene. Cells were infected by MHV-68 at an MOI of 2 in the presence of CHX or PAA or left untreated. Total RNA was collected at 0, 8, 12, and 24 h postinfection and analyzed by Northern blotting with a probe targeting the ORF48 coding region. N, none treated; C, CHX treated; P, PAA treated.

RTA activates ORF48 via 48pRRE in a reporter assay.

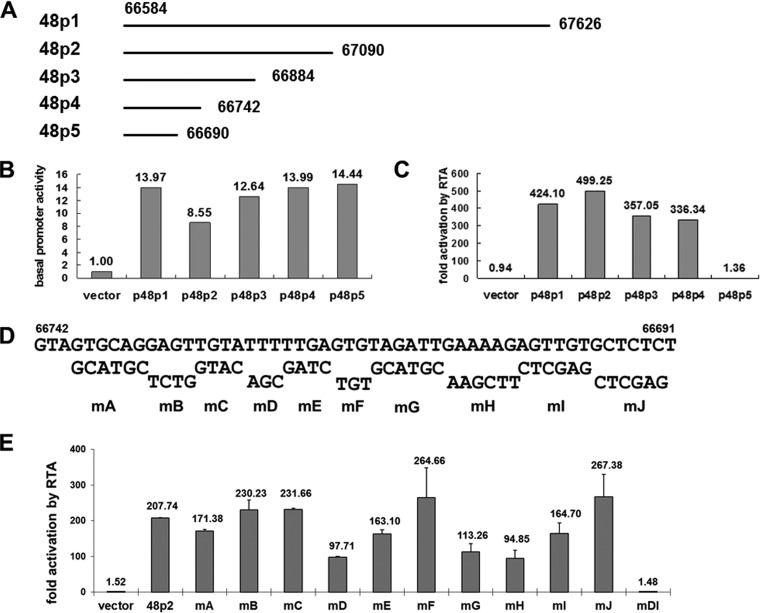

RTA, expressed as an immediate early gene product, acts as a master regulator of lytic replication for MHV-68 and can activate several viral early genes (30–32). Since ORF48 is expressed as an early gene, we sought to examine whether it can also be activated by RTA. We first employed a luciferase reporter system to test whether the ORF48 promoter can be activated by RTA. We cloned a 1-kb fragment upstream of the ORF48 translational start codon (GenBank accession number NC_001826.2, nt 66584 to nt 67626) (Fig. 1A and 2A) into the pGL3-basic vector to generate reporter plasmid p48p1 and then cotransfected p48p1 with pCMVHA-mRTA (or pCMV-HA as a vector control) into 293T cells to test the effect of RTA protein on the transcriptional activity from ORF48 promoter. As shown in Fig. 2B and C, p48p1 displayed some basal promoter activity (Fig. 2B) that can be increased by more than 400-fold in the presence of RTA (Fig. 2C), demonstrating strong activation by RTA. In comparison, the control plasmid pGL3-basic was not activated (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG 2.

RTA activates the ORF48 promoter in the reporter assay. (A) Diagram of the 1-kb ORF48 promoter and a series of 5′ deletion fragments. (B and C) Dual-luciferase reporter assays showing the basal activities of the ORF48 promoter constructs and their activation by RTA. (D) Diagram of systematic site-directed mutations of 48pRRE. The wild-type sequences are shown on the top, and the mutated sequences and the names of the corresponding reporter plasmids (mA to mJ) are shown below. (E) Reporter assays with the 48pRRE mutants identified nucleotides critical for 48pRRE function. The fold activation by RTA for the vector is significantly different from that for each of the ORF48 promoter reporter plasmids except mDI (P < 0.01). The difference between activation for 48p2 and that for each of mD, mE, mG, mH, and mI is also significant (P < 0.01).

In order to map the ORF48 promoter's essential region that mediates RTA activation, we constructed a series of 5′ deletion plasmids based on p48p1, named p48p2 to p48p5 (Fig. 2A), and applied them to the reporter assay as described above. Results demonstrated that whereas these constructs displayed similar basal promoter activities, the level of activation by RTA remained at over 300-fold for p48p1 to p48p4 but fell dramatically to less than 2-fold for p48p5 (Fig. 2B and C), indicating that an RTA-responsive element (RRE), designated 48pRRE, lies between nt 66691 and nt 66742 in the MHV-68 genomic region.

To identify the critical nucleotides mediating RTA activation, 10 reporter plasmids with site-directed mutations were constructed based on p48p2 (Fig. 2D) and tested for their activation level by RTA. Mutations in two small clusters of nucleotides in the ORF48 promoter (one consisting of sites D and E and one consisting of sites G, H, and I) decreased the level of activation by RTA to approximately half of that of p48p2 (Fig. 2E). Combined mutations in sites D and I, termed mDI, abolished the activation of ORF48 promoter by RTA (Fig. 2E), indicating that nucleotides in sites D and I are critical for the function of 48pRRE.

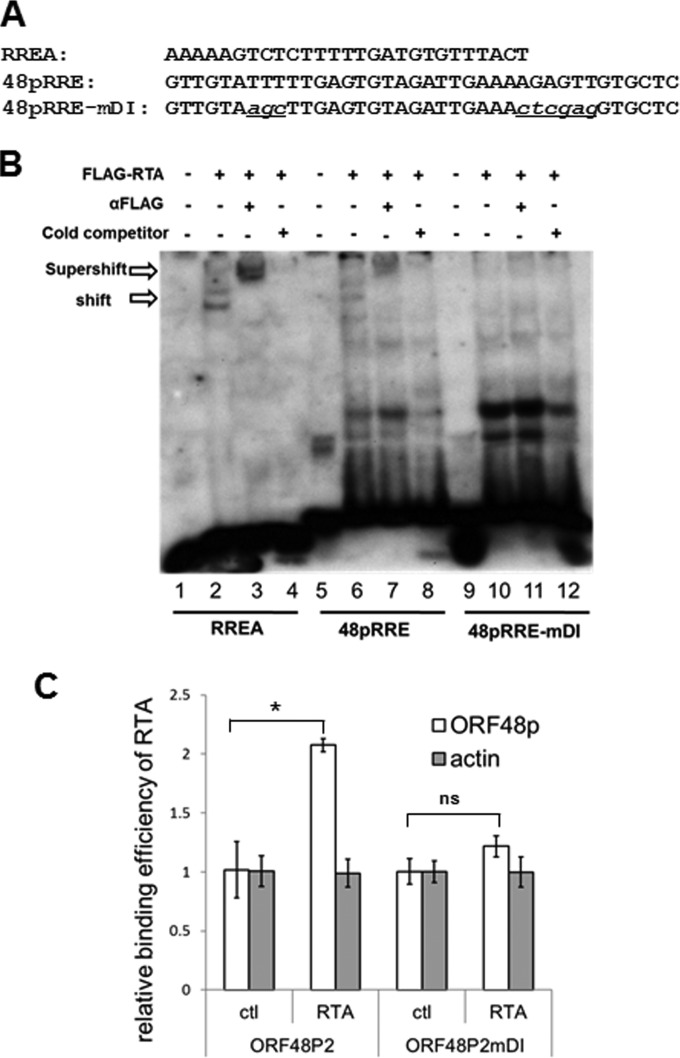

RTA binds to 48pRRE directly.

Gammaherpesvirus RTA can activate viral promoters through two distinct mechanisms: by directly binding to RRE and indirectly by activating other transcription factors (14, 19). To explore the mechanism of how RTA activates ORF48 promoter, we first tested whether RTA can bind to 48pRRE directly in vitro in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). A previously identified MHV-68 RTA binding sequence (RREA) (32) was included as a control (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, FLAG-RTA containing nuclear extract shifted both probes RREA and 48pRRE but with different affinities (lanes 2 and 6). The RTA-bound complexes formed on RREA or 48pRRE were supershifted by a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (lanes 3 and 7), while unlabeled probes competed for the binding of RTA to RREA or 48pRRE (lanes 4 and 8), demonstrating the specificity of RTA binding to 48pRRE. Introducing mutation mDI into 48pRRE abolished the binding of RTA (lanes 9 to 12), indicating that the nucleotides in sites D and I, which are critical for the function of 48pRRE in a reporter assay, also play critical roles in mediating direct binding by RTA.

FIG 3.

RTA binds to 48pRRE in vitro and in vivo. (A) Sequences of biotin-labeled probes used in EMSA. (B) RTA specifically binds to 48pRRE in EMSA. Nuclear extract from pFLAGCMV2-RTA-transfected 293T cells was incubated with biotin-labeled probes (RREA, 48pRRE, and 48pRRE-mDI). In supershift reactions, anti-FLAG antibody was added; in competition reactions, a 200-fold excess amount of unlabeled RREA oligonucleotides was added. (C) RTA associates with ORF48 promoter in a ChIP assay. 293T cells were transfected with ORF48 promoter plasmids (p48p2 or p48p2-mDI) and pFLAGCMV2-RTA (or empty vector pFLAGCMV2 as a control). A ChIP assay was performed by cross-linking DNA-protein complexes and immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody-conjugated beads. Quantitative PCR was performed with primers specific for the ORF48 promoter region or actin coding region as a control. Three independent experiments were performed, and the relative amount of immunoprecipitated DNA was first normalized to the input DNA and then compared to that of control vector (pFLAGCMV2)-transfected cells. *, P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05.

We next examined whether RTA also associates with the ORF48 promoter in vivo. We cotransfected 293T cells with the FLAG-RTA expression plasmid (or with vector as a control) and the reporter plasmid containing the ORF48 promoter (ORF48P2 or ORF48P2mDI) and then analyzed the binding of RTA to the ORF48 promoter with a ChIP-quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay. As shown in Fig. 3C, RTA is specifically associated with the wild-type ORF48 promoter but not with either the mDI mutant or actin coding region. Collectively, our results from EMSA and ChIP assay indicate that RTA activates the ORF48 promoter via direct binding.

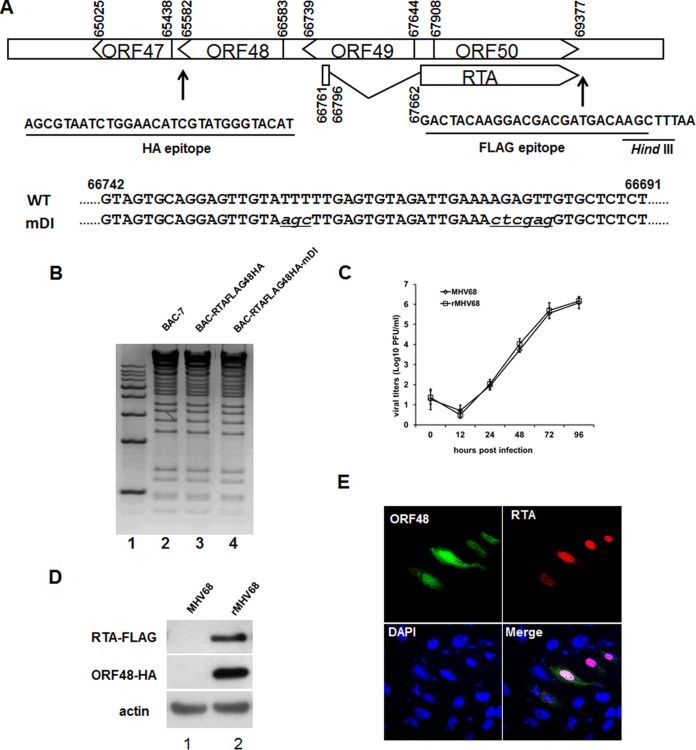

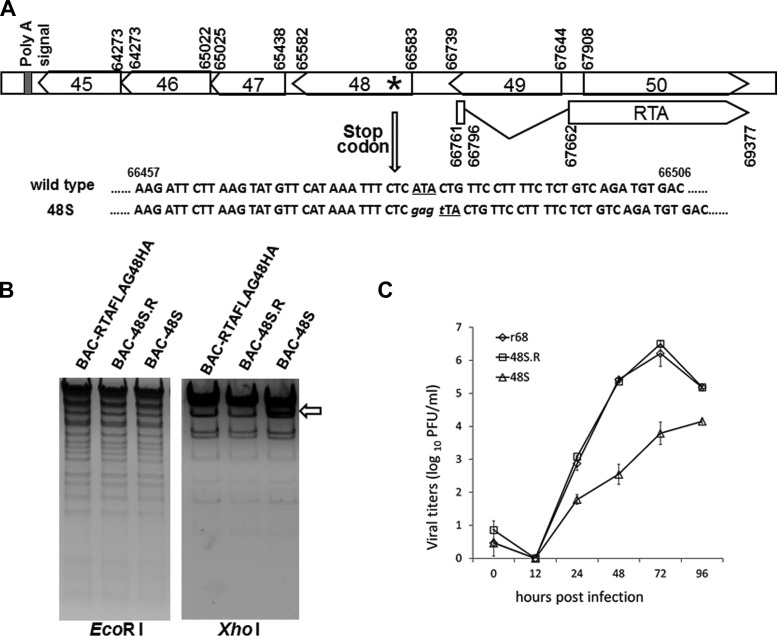

The expression of ORF48 relies on 48pRRE and RTA during de novo infection.

The above observations suggested that RTA activated the ORF48 promoter in the reporter assay and that activation was mediated by 48pRRE located in the ORF48 promoter. We next investigated whether RTA could activate the expression of ORF48 in the context of the viral genome during MHV-68 de novo infection. To facilitate the analysis of endogenous RTA and ORF48 expression, we first took advantage of the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) system (45, 46) to construct a recombinant MHV-68 BAC, termed BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA, using a two-step allelic exchange method (40). This recombinant BAC expresses a FLAG tag on the C terminus of RTA and an HA tag on the C terminus of ORF48 (Fig. 4A). The recombinant BAC plasmid (BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA) was validated by both restriction enzyme digestion (Fig. 4B) and direct sequencing analysis. The BAC plasmid was then transfected into 293T cells to reconstitute virus (named rMHV68). To verify that this doubly tagged virus has no deficiency in lytic gene expression, we compared its growth kinetics with that of the wild-type MHV-68 and found no obvious difference (Fig. 4C). Moreover, the expression of RTA and ORF48 proteins during de novo infection can be successfully detected by Western blotting (Fig. 4D), suggesting that rMHV68 virus can be utilized as an important tool to study the expression kinetics, function, and localization of RTA and ORF48 proteins in the context of viral genome.

FIG 4.

Construction of an RTA and ORF48 doubly tagged MHV-68 virus and an mDI mutant virus. (A) Diagram of the sequences and locations of the FLAG and HA tags on the viral genome, as well as the sequence of mDI mutant virus in comparison to that of the wild-type virus. (B) Restriction enzyme digestion analysis of wild-type MHV-68 BAC-7, BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA, and BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA-mDI. (C) Multiple-step growth curves of wild-type MHV-68 and doubly tagged virus (rMHV68). (D) Detection of FLAG-tagged RTA and HA-tagged ORF48 during wild-type MHV-68 and rMHV68 de novo infection. Cells were infected at an MOI of 3 for 12 h and then collected for Western blotting. (E) Cellular localization of ORF48 and RTA during de novo infection. Vero cells were infected with rMHV68 for 12 h and then subjected to an indirect immunofluorescence assay. Green, ORF48; red, RTA.

By taking advantage of this doubly tagged recombinant virus, rMHV68, we first determined the subcellular localization of ORF48 during de novo infection. Briefly, Vero cells were infected with rMHV68 for 12 h at an MOI of 0.5 and then subjected to an immunofluorescence assay with antibodies against the FLAG and HA epitopes. Detection with a confocal laser microscope demonstrated that the endogenous ORF48 protein was distributed in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and RTA mainly displayed a nuclear localization (Fig. 4E).

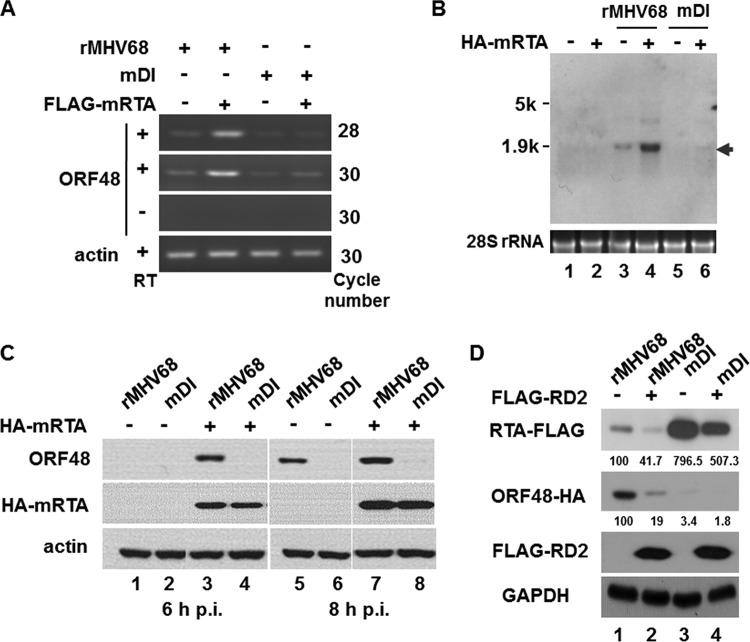

To confirm the role of the RTA-responsive element 48pRRE in driving ORF48 expression in the context of MHV-68 lytic replication, we next generated a mutant BAC, BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA-mDI, on the basis of BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA (Fig. 4A and B). The corresponding mutant virus, named rMHV68-mDI (mDI), was also reconstituted by transfecting BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA-mDI plasmid into cultured cells. Utilizing these recombinant viruses, we first investigated the role of RTA in regulating ORF48 transcription by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) during de novo infection at a very early time after viral infection. As shown in Fig. 5A, exogenous RTA enhanced transcription of ORF48 from the viral genome at 4 h after MHV-68 infection (lanes 1 and 2), and such enhancement was almost diminished by disruption of 48pRRE (rMHV68-mDI) (lanes 3 and 4). To confirm this result, Northern blotting was carried out (Fig. 5B). In rMHV68 infected cells, introduction of exogenous RTA increased the transcription level of ORF48 (Fig. 5B, lanes 3 and 4); however, in cells infected with rMHV68-mDI, ORF48 could barely be detected, especially in the absence of exogenous RTA protein (Fig. 5B, lanes 5 and 6). We thus concluded that, during the very early stage of MHV-68 de novo infection, cis element 48pRRE mediated the activation of ORF48 transcription by RTA (Fig. 5B, compare lanes 3 and 5) and that the activation could be further enhanced by exogenous RTA.

FIG 5.

RTA activates transcription and expression of ORF48 via 48pRRE from MHV-68 genome. (A and B) Recombinant virus rMHV68 or rMHV68-mDI was used to infect 293T cells which had been transfected with pCMVHA-mRTA (or pCMV-HA) 24 h before infection. Four hours after infection, total RNA was isolated for analyzing ORF48 expression by RT-PCR with primers specific to the ORF48 coding region (nt 65852 to 65997) (A) or Northern blotting with a probe targeting the ORF48 coding region (B). (C) RTA activated the expression of endogenous ORF48 protein via 48pRRE. Transfection and infection were performed as described above, and cells were harvested at the indicated time points, followed by Western blotting. (D) A dominant negative form of RTA (FLAG-RD2) inhibited the expression of endogenous ORF48. Expression plasmid FLAG-RD2 or a vector control was transfected into cells 24 h prior to infection with rMHV68 or rMHV68-mDI. Cells were collected at 8 h after infection and analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against the HA epitope (ORF48) and FLAG epitope (endogenous RTA and FLAG-RD2). The relative expression levels of endogenous RTA-FLAG and ORF48-HA were calculated with ImageJ.

We next examined whether the protein level of ORF48 would also increase as a result of RTA activation. We transfected 293T cells with pCMVHA-mRTA (or pCMVHA) and after 24 h individually infected the cells with rMHV68 or the rMHV68-mDI mutant for 6 and 8 h, which are the early time points when ORF48 protein is detectable by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 5C, in cells infected with rMHV68, ORF48 expression notably increased in the presence of exogenous RTA (lanes 1 and 3). In contrast, in cells infected with rMHV68-mDI, ORF48 expression could not be detected in either the presence or absence of exogenous RTA (lanes 2 and 4); very weak expression of ORF48 was observed in rMHV68-mDI-infected cells only in the presence of exogenous RTA at 8 h postinfection (lane 8). These data provided further evidence that 48pRRE is critical for ORF48 expression.

To further investigate the involvement of RTA in activating ORF48, we also employed a dominant negative form of MHV-68 RTA, FLAG-RD2 (339 amino acids [aa]) (47). Cells were transfected with FLAG-RD2 (or empty vector as a control) and infected with rMHV68 or rMHV68-mDI. As shown in Fig. 5D, in the presence of FLAG-RD2, the expression level of the endogenous RTA was reduced to 41.7% of that in the vector-transfected cells (Fig. 5D, first panel, lanes 1 and 2), consistent with auto-activation of RTA that was reported previously (22, 47). However, the expression level of ORF48 in cells infected with rMHV68 was more severely repressed, to 19%, by FLAG-RD2 (Fig. 5D, second panel, lanes 1 and 2), indicating that expression of ORF48 relies on functional RTA. In cells infected with rMHV68-mDI, the expression level of ORF48 was reduced to only 3.4% of that of rMHV68, and this was further reduced to 1.8% in the presence of FLAG-RD2 (Fig. 5D, second panel, lanes 1, 3, and 4). Interestingly, the expression level of RTA increased to approximately eight times that in cells infected with rMHV68, but this was again reduced by the presence of FLAG-RD2 (Fig. 5D, first panel, lanes 1, 3, and 4). Therefore, knocking down RTA function resulted in decreased ORF48 expression, demonstrating that the expression of ORF48 depends on functional RTA during de novo infection.

Collectively, these results demonstrated that 48pRRE is critical for ORF48 expression and that RTA activates ORF48 expression through 48pRRE in the context of viral infection.

Construction and characterization of an ORF48-null MHV-68 virus in vitro.

Having characterized the transcriptional regulation of ORF48, we next sought to investigate the role of ORF48 during MHV-68 de novo infection. In order to precisely analyze the function of ORF48 in vitro and in vivo, we constructed an ORF48-null mutant (designated BAC-48S) based on the BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA through site-specific mutagenesis (Fig. 6A). Restriction enzyme analysis showed that the 48S BAC exhibited the same digestion pattern as RTAFLAG-48HA BAC (Fig. 6B), suggesting that no undesired mutation was introduced. DNA sequencing further confirmed that the stop codon mutation was successfully inserted into the MHV-68 ORF48 region (data not shown). To ensure that any phenotype displayed by 48S is associated with the ORF48-null mutation but not due to any additional recombination or accidental mutation on the MHV-68 genome, a revertant of BAC-48S (named BAC-48S.R) was also generated from BAC-48S by replacing the ORF48-STOP with a wild-type copy of ORF48. In restriction enzyme digestions and DNA sequencing analyses, the 48S.R BAC exhibited the same fragment patterns as RTAFLAG-48HA BAC (Fig. 6B, and data not shown).

FIG 6.

Construction and characterization of an MHV-68 ORF48-null virus. (A) Schematic illustration of the MHV-68 locus harboring the mutation in the ORF48-null mutant. Briefly, nucleotide A at position 66487 is mutated to T in order to form a translation termination codon on the viral genome (102 nt downstream of the translation start codon for ORF48). (B) Restriction enzyme digestion analysis of BAC-RTAFLAG-48HA and the ORF48-null and revertant mutant. (C) Multiple-step growth curves of the recombinant viruses. NIH 3T3 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.01, cells and supernatants were harvested at the indicated time points postinfection, and viral titers were determined by plaque assay.

The BAC plasmids of wild-type, null-mutant, and revertant were then individually transfected into cell cultures to reconstitute rMHV68, r48S, and r48S.R viruses. To facilitate the in vivo infection study, the BAC backbone sequence of the rMHV68, r48S, and r48S.R viruses was further removed by Cre recombination in 293T cells (41) to reconstitute r68, 48S, and 48S.R viruses separately. To examine the role of ORF48 during MHV-68 lytic replication in vitro, we first employed multiple-step growth curve analysis. As shown in Fig. 6C, replication of the 48S virus was remarkably slower than that of r68 and 48S.R in NIH 3T3 cells at and after 24 h postinfection, indicating that ORF48 is important for MHV-68 lytic replication in cell culture.

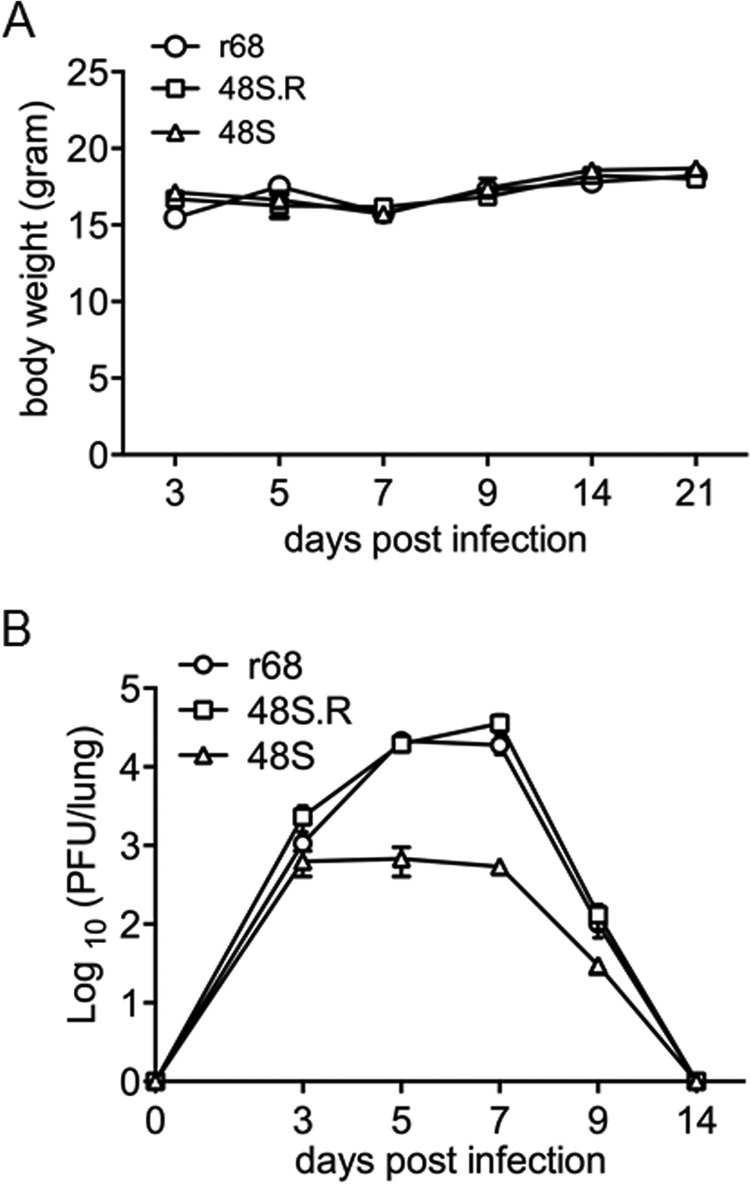

ORF48 plays an important role during lytic infection in the lung and the establishment of latency in the spleen.

We next sought to explore the in vivo function of ORF48. First, BALB/c mice were intranasally infected with 500 PFU of r68, 48S, or 48S.R virus. The body weights of the mice infected with each virus displayed no significant difference (Fig. 7A). As MHV-68 establishes transient lytic replication in lung epithelial cells after intranasal infection, we tested the titer of each virus in the lung at various time points. The replication levels and kinetics of r68 and 48S.R were very similar to each other. 48S virus, on the other hand, replicated much less efficiently than r68 or 48S.R, especially at peak time points, resulting in approximately 30-fold and 50-fold lower titers at 5 and 7 days postinfection, respectively (Fig. 7B). The attenuated growth of 48S virus during acute infection suggested that ORF48 is important for robust lytic replication of MHV-68 in the lung of infected mice.

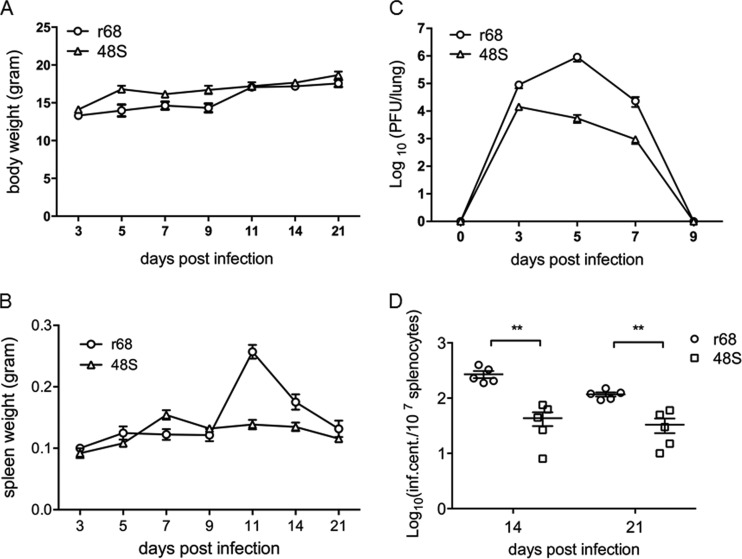

FIG 7.

MHV-68 ORF48-null virus displayed a significant growth defect in the lung of infected mice. Results from one representative experiment are shown. (A) Body weights of BALB/c mice infected with 500 PFU of each indicated virus. (B) Infectious virus load in the lungs. The lungs were removed from infected mice at the indicated time points postinfection, and tissue homogenates were used to measure viral titers by standard plaque assays. Each time point represents data from five animals, and error bars represent standard deviations.

After being cleared from the lung by the host immune system, MHV-68 further establishes latency in the spleen, with a peak viral load at 2 to 3 weeks postinfection (42, 48, 49). At this peak time of viral latency, the mice exhibit a mononucleosis-like symptom due to an amplification of lymphocytes, which causes a significant increase in spleen weight. Indeed, infection of mice with r68, 48S, or 48S.R led to a gradual increase in spleen weight that reached its peak at day 14 postinfection. However, the spleens of 48S virus-infected mice were smaller than those of mice infected with r68 or 48S.R on days 9, 14, and 21 postinfection (Fig. 8A and B). To test the latent viral genome load, we prepared single-cell suspensions from spleens harvested at 14 and 21 days p.i. and quantified the genome copy numbers in splenocytes by real-time PCR. Whereas similar levels of viral genome copy numbers were detected in the splenocytes from r68- or 48S.R-infected mice at 14 and 21 days postinfection, considerably fewer viral genomes were detected from 48S-infected mice (Fig. 8C). These results implied that although the ORF48-null virus was able to establish splenic latency, efficiency was impaired.

FIG 8.

ORF48 is important for MHV-68 latent infection in the spleen. Results from one representative experiment are shown. (A) The spleen weights of mice infected with 500 PFU of viruses at the indicated days postinfection. (B) Representative images of spleens from mice infected at 14 days postinfection. (C) Quantitative analysis of the viral DNA load in the splenocytes from r68-, 48S.R-, or 48S-infected mice. Real-time PCR was performed using primers specific for MHV-68 ORF65. All time points represent results from five animals, and error bars represent standard deviations. (D to F) Levels of reactivating viruses in the spleens of infected mice. Single-cell suspensions were obtained from spleens harvested at the indicated days postinfection and subjected to infectious center assays to determine the virus reactivation efficiency (D). Ex vivo limiting dilution assays were also performed with the same single-cell suspensions harvested at day 14 (E) and day 21 (F) postinfection. For each virus infection at each time point, splenocytes from five infected mice (5 × 106 cells each) were pooled and analyzed in the limiting dilution assay. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (comparison between results for r68 or 48S.R and 48S).

To further assess the level of viral latency for r68, 48S.R, and 48S infection, infectious center assays (Fig. 8D) and ex vivo limiting dilution assays were performed on splenocytes from infected mice at the time points indicated (Fig. 8E and F) (42, 50). Again, in the splenocytes from mice infected with 48S, viral reactivation efficiency was significantly lower than that in those from mice infected with r68 or 48S.R, indicating that although the ORF48-null virus is able to establish splenic latency, the efficiency is largely impaired.

The above infection experiments were performed using a relatively low inoculum dose of 500 PFU. To test whether a higher-dose infection would overcome the impairment of lytic replication and establishment of latency displayed by ORF48 deficiency, we infected mice intranasally with 5 × 104 PFU of r68 or 48S virus and repeated the experiment. Similar to the result from infection with 500 PFU virus, the body weight of mice infected with 48S virus showed no obvious change compared to mice infected with r68 virus (Fig. 9A). 48S virus replicated much less efficiently than r68 in the lung of infected mice, resulting in approximately 100-fold and 50-fold lower titers at 5 and 7 days postinfection, respectively (Fig. 9B), induced less splenomegaly at days 11 and 14 postinfection (Fig. 9C), and showed impaired reactivation efficiency at the two time points tested (Fig. 9D). Therefore, a higher-dose MHV-68 infection of mice did not rescue the impairment displayed by the ORF48-null mutation in either lytic replication or latency.

FIG 9.

A higher dose of inoculum intranasally does not rescue the impairment displayed by ORF48-null mutation in either lytic replication or latency. (A) Body weights of BALB/c mice infected with 5 × 104 PFU of each indicated virus. (B) Viral titers in lungs from infected mice were determined at 3, 5, 7, and 9 days p.i. (C) Measurement of spleen weights at indicated days after inoculation. (D) Levels of reactivating viruses in the spleens of infected mice. Single-cell suspensions were obtained from spleens harvested at days 14 and 21 postinfection and subjected to infectious center assays. For all experiments, each time point represents data from five animals, and error bars represent standard deviations. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01 (comparison between results for r68 and 48S).

Collectively, these results indicated that after infection of mice via the respiratory route, regardless of the viral inoculum dose, ORF48 plays an important role in MHV-68 lytic replication in the lung as well as in latency establishment and viral reactivation from splenocytes.

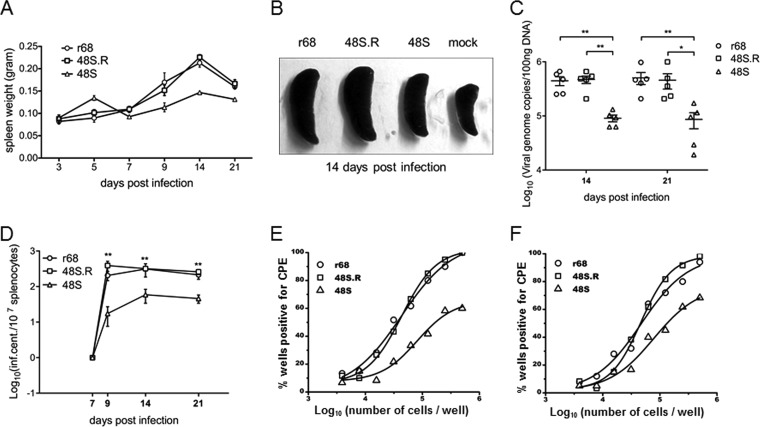

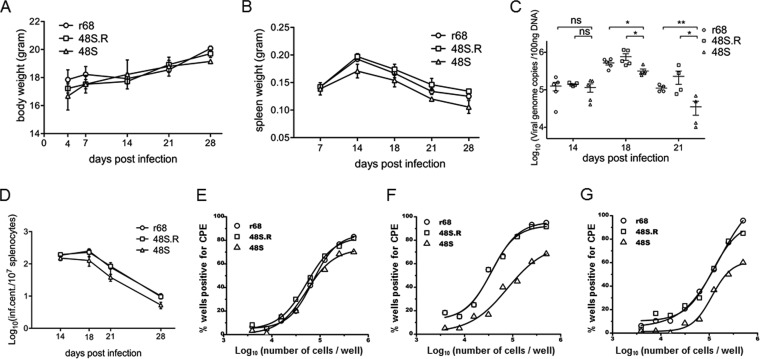

ORF48 plays an important role in the establishment of MHV-68 latency through intraperitoneal infection.

Through the intranasal inoculation route, MHV-68 first undergoes acute lytic infection in the lung of infected mice before being transmitted to and establishing latency in the spleen (51). Therefore, the lower level of latency achieved by 48S virus, as we observed above, may be due to attenuated acute replication in the lung. Alternatively, ORF48 may play an important role in the establishment of latency regardless of lytic replication in the lung. To more directly assess the effect of ORF48 on viral latency, we next performed intraperitoneal inoculation of mice to bypass acute viral replication in the lung. We inoculated BALB/c mice intraperitoneally with 500 PFU of either r68, 48S.R, or 48S. After 14, 18, 21, and 28 days of infection, mice were sacrificed, and spleens were harvested and examined for viral latency. The body weights of infected mice increased gradually with no significant difference among these three MHV-68 viruses (Fig. 10A). Although the spleen weights from all three infected groups peaked at day 14 postinfection, 48S induced less splenomegaly at all time points on and after 14 days than r68 and 48S.R (Fig. 10B). To quantitatively analyze the level of viral latency, we first measured the viral genome copies in the splenocytes and found that all three viruses were able to establish latency in the spleen at day 14 postinfection; furthermore, at days 18 and 21 postinfection, the viral genome load in the splenocytes of 48S-infected mice was significantly lower than that of r68- or 48S.R-infected mice (Fig. 10C). Consistent with these observations, infectious center assays revealed that these three viruses exhibited comparable frequencies of reactivation at day 14 postinfection; however, the reactivation efficiency for 48S virus was lower than that of r68 and 48S.R at days 18, 21, or 28 postinfection (Fig. 10D). Limiting dilution assays on splenocytes harvested at days 18, 21, and 28 confirmed the reduction in reactivation efficiency for 48S (Fig. 10E, F, and G). Taken together, these results demonstrated that MHV-68 ORF48 plays an important function in viral latency in splenocytes regardless of lytic replication in the lung.

FIG 10.

ORF48 is important for MHV-68 latent infection during intraperitoneal inoculation. Results from one representative experiment are shown. (A) Body weights of mice at indicated days after infection with 500 PFU viruses. (B) Spleen weights at indicated days postinfection. (C) Quantitation of viral DNA in the splenocytes. ns, not significant (P > 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, comparing the results between r68 or 48S.R and 48S. (D to G) Levels of viral reactivation from splenocytes. Single-cell suspensions were obtained from the spleens harvested at days 14, 18, 21, and 28 postinfection and examined for reactivation efficiency by infectious center assays (D). Single-cell suspensions from day 18 (E), day 21(F), and day 28 (G) were also subjected to ex vivo limiting dilution assays. For each virus infection at each time point, splenocytes from five infected mice (5 × 106 cells each) were pooled and analyzed.

In this study, we characterized the transcription unit of MHV-68 ORF48 and identified that it is expressed as a viral early gene during lytic replication (Fig. 1). We further found that ORF48 is activated by RTA both in reporter assays and during MHV-68 de novo infection and mapped the cis element in the ORF48 promoter that mediates its activation by RTA (Fig. 2 to 5). RTA functions as the molecular switch for MHV-68 and KSHV and activates the expression of many downstream viral lytic genes. Three viral genes, ORF18, ORF57, and ORF72, have previously been reported to be regulated by MHV-68 RTA (30–32). Although the RREs for ORF57 and ORF72 were identified, the mechanisms responsible for RTA controlling these elements were not investigated (30, 31). For ORF18, a 27-bp RRE was identified through a combination of reporter assay, EMSA, and viral genetics (32). The 48pRRE mapped in this study (Fig. 2) does not share significant homology with the RREs of the ORF57 and ORF72 promoters. 48pRRE does contain some of the core sequences of ORF18 RRE. Consistently, our EMSA and ChIP assay (Fig. 3) showed that RTA binds 48pRRE in vitro and in vivo, indicating that RTA activates the ORF48 promoter in a direct-binding manner even though we cannot exclude the possibility that other cellular factor(s) may assist with RTA's binding to 48pRRE.

ORF48 is conserved among all gammaherpesviruses, but its function remained largely unclear. In this study, by introducing a stop codon into the coding region of ORF48 to construct an ORF48-null virus, we examined the function of ORF48 both in vitro and in vivo. The results showed that the viral titer of ORF48-null virus decreased more than 50-fold compared to that of wild-type MHV-68 (Fig. 6), indicating that ORF48 is important for MHV-68 lytic replication and virion production in cell culture. In addition, ORF48-null virus not only replicated less efficiently in the lung of infected mice but also exhibited a reduced level of latency in the spleen and was reactivated with impaired efficiency (Fig. 7 to 10), regardless of the inoculum doses and routes. Although the mechanism involved needs further investigation, our data overall proved that ORF48, as an RTA-responsive gene product, plays important roles in the MHV-68 life cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ren Sun, Ting-Ting Wu, Seungmin Hwang, Kevin Lee, Yuchen Xiao, and members of the Deng laboratory for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (grant numbers 30930007 and 81325012) and from the Ministry of Science and Technology (973 Program, grant number 2011CB504805) of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stevenson PG. 2004. Immune evasion by gamma-herpesviruses. Curr Opin Immunol 16:456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenner RG, Albà MM, Boshoff C, Kellam P. 2001. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent and lytic gene expression as revealed by DNA arrays. J Virol 75:891–902. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.891-902.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samols MA, Hu J, Skalsky RL, Renne R. 2005. Cloning and identification of a microRNA cluster within the latency-associated region of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 79:9301–9305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.9301-9305.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dittmer D, Lagunoff M, Renne R, Staskus K, Haase A, Ganem D. 1998. A cluster of latently expressed genes in Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 72:8309–8315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bais C, Santomasso B, Coso O, Arvanitakis L, Raaka EG, Gutkind JS, Asch AS, Cesarman E, Gerhengorn MC, Mesri EA. 1998. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature 391:86–89. doi: 10.1038/34193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi YB, Nicholas J. 2008. Autocrine and paracrine promotion of cell survival and virus replication by human herpesvirus 8 chemokines. J Virol 82:6501–6513. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02396-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renne R, Lagunoff M, Zhong W, Ganem D. 1996. The size and conformation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) DNA in infected cells and virions. J Virol 70:8151–8154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russo JJ, Bohenzky RA, Chien M-C, Chen J, Yan M, Maddalena D, Parry JP, Peruzzi D, Edelman IS, Chang Y. 1996. Nucleotide sequence of the Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV8). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:14862–14867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virgin HW IV, Latreille P, Wamsley P, Hallsworth K, Weck KE, Dal Canto AJ, Speck SH. 1997. Complete sequence and genomic analysis of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 71:5894–5904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nash AA, Dutia BM, Stewart JP, Davison AJ. 2001. Natural history of murine gamma-herpesvirus infection. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 356:569–579. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simas JP, Efstathiou S. 1998. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68: a model for the study of gammaherpesvirus pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol 6:276–282. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun R, Lin SF, Gradoville L, Yuan Y, Zhu F, Miller G. 1998. A viral gene that activates lytic cycle expression of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:10866–10871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Pavlova IV, Virgin HW IV, Speck SH. 2000. Characterization of gammaherpesvirus 68 gene 50 transcription. J Virol 74:2029–2037. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.4.2029-2037.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staudt MR, Dittmer DP. 2007. The Rta/Orf50 transactivator proteins of the gamma-herpesviridae. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol 312:71–100. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34344-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu TT, Usherwood EJ, Stewart JP, Nash AA, Sun R. 2000. Rta of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 reactivates the complete lytic cycle from latency. J Virol 74:3659–3667. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.8.3659-3667.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukac DM, Renne R, Kirshner JR, Ganem D. 1998. Reactivation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection from latency by expression of the ORF 50 transactivator, a homolog of the EBV R protein. Virology 252:304–312. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukac DM, Kirshner JR, Ganem D. 1999. Transcriptional activation by the product of open reading frame 50 of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for lytic viral reactivation in B cells. J Virol 73:9348–9361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller G, El-Guindy A, Countryman J, Ye J, Gradoville L. 2007. Lytic cycle switches of oncogenic human gammaherpesviruses. Adv Cancer Res 97:81–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)97004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng H, Liang Y, Sun R. 2007. Regulation of KSHV lytic gene expression. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol 312:157–183. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34344-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowser BS, DeWire SM, Damania B. 2002. Transcriptional regulation of the K1 gene product of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 76:12574–12583. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12574-12583.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, Ueda K, Sakakibara S, Okuno T, Yamanishi K. 2000. Transcriptional regulation of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral interferon regulatory factor gene. J Virol 74:8623–8634. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.18.8623-8634.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng H, Young A, Sun R. 2000. Auto-activation of the rta gene of human herpesvirus-8/Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Gen Virol 81:3043–3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukac DM, Garibyan L, Kirshner JR, Palmeri D, Ganem D. 2001. DNA binding by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic switch protein is necessary for transcriptional activation of two viral delayed early promoters. J Virol 75:6786–6799. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6786-6799.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakakibara S, Ueda K, Chen J, Okuno T, Yamanishi K. 2001. Octamer-binding sequence is a key element for the autoregulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF50/Lyta gene expression. J Virol 75:6894–6900. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.15.6894-6900.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song MJ, Brown HJ, Wu TT, Sun R. 2001. Transcription activation of polyadenylated nuclear RNA by Rta in human herpesvirus 8/Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 75:3129–3140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3129-3140.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L, Chiu J, Lin JC. 1998. Activation of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) thymidine kinase (TK) TATAA-less promoter by HHV-8 ORF50 gene product is SP1 dependent. DNA Cell Biol 17:735–742. doi: 10.1089/dna.1998.17.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong J, Papin J, Dittmer D. 2001. Differential regulation of the overlapping Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus vGCR (orf74) and LANA (orf73) promoters. J Virol 75:1798–1807. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.4.1798-1807.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang Y, Chang J, Lynch SJ, Lukac DM, Ganem D. 2002. The lytic switch protein of KSHV activates gene expression via functional interaction with RBP-Jκ (CSL), the target of the Notch signaling pathway. Genes Dev 16:1977–1989. doi: 10.1101/gad.996502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng H, Song MJ, Chu JT, Sun R. 2002. Transcriptional regulation of the interleukin-6 gene of human herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus). J Virol 76:8252–8264. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8252-8264.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen RD III, DeZalia MN, Speck SH. 2007. Identification of an Rta responsive promoter involved in driving γHV68 v-cyclin expression during virus replication. Virology 365:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavlova I, Lin CY, Speck SH. 2005. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 Rta-dependent activation of the gene 57 promoter. Virology 333:169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong Y, Qi J, Gong D, Han C, Deng H. 2011. Replication and transcription activator (RTA) of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 binds to an RTA-responsive element and activates the expression of ORF18. J Virol 85:11338–11350. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00561-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu FX, Cusano T, Yuan Y. 1999. Identification of the immediate-early transcripts of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol 73:5556–5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bortz E, Whitelegge JP, Jia Q, Zhou ZH, Stewart JP, Wu TT, Sun R. 2003. Identification of proteins associated with murine gammaherpesvirus 68 virions. J Virol 77:13425–13432. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13425-13432.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arumugaswami V, Sitapara R, Hwang S, Song MJ, Ho TN, Su NQ, Sue EY, Kanagavel V, Xing F, Zhang X, Zhao M, Deng H, Wu TT, Kanagavel S, Zhang L, Dandekar S, Papp J, Sun R. 2009. High-resolution functional profiling of a gammaherpesvirus RTA locus in the context of the viral genome. J Virol 83:1811–1822. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02302-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.May JS, Coleman HM, Smillie B, Efstathiou S, Stevenson PG. 2004. Forced lytic replication impairs host colonization by a latency-deficient mutant of murine gammaherpesvirus-68. J Gen Virol 85:137–146. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z, Tang H, Huang H, Deng H. 2009. RTA promoter demethylation and histone acetylation regulation of murine gammaherpesvirus 68 reactivation. PLoS One 4:e4556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gong D, Qi J, Arumugaswami V, Sun R, Deng H. 2009. Identification and functional characterization of the left origin of lytic replication of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. Virology 387:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qi J, Gong D, Deng H. 2011. CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins play a role in oriLyt-dependent genome replication during MHV-68 de novo infection. Protein Cell 2:463–469. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jia Q, Wu TT, Liao HI, Chernishof V, Sun R. 2004. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 open reading frame 31 is required for viral replication. J Virol 78:6610–6620. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6610-6620.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu TT, Liao HI, Tong L, Leang RS, Smith G, Sun R. 2011. Construction and characterization of an infectious murine gammaherpesivrus-68 bacterial artificial chromosome. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011:926258. doi: 10.1155/2011/926258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sunil-Chandra NP, Efstathiou S, Nash AA. 1992. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 establishes a latent infection in mouse B lymphocytes in vivo. J Gen Virol 73:3275–3279. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-12-3275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rickabaugh TM, Brown HJ, Martinez-Guzman D, Wu TT, Tong L, Yu F, Cole S, Sun R. 2004. Generation of a latency-deficient gammaherpesvirus that is protective against secondary infection. J Virol 78:9215–9223. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9215-9223.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinez-Guzman D, Rickabaugh T, Wu TT, Brown H, Cole S, Song MJ, Tong L, Sun R. 2003. Transcription program of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 77:10488–10503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10488-10503.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adler H, Messerle M, Wagner M, Koszinowski UH. 2000. Cloning and mutagenesis of the murine gammaherpesvirus 68 genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. J Virol 74:6964–6974. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.15.6964-6974.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu TT, Park T, Kim H, Tran T, Tong L, Martinez-Guzman D, Reyes N, Deng H, Sun R. 2009. ORF30 and ORF34 are essential for expression of late genes in murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 83:2265–2273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01785-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu TT, Tong L, Rickabaugh T, Speck S, Sun R. 2001. Function of Rta is essential for lytic replication of murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 75:9262–9273. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.9262-9273.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flano E, Husain SM, Sample JT, Woodland DL, Blackman MA. 2000. Latent murine gamma-herpesvirus infection is established in activated B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages. J Immunol 165:1074–1081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewart JP, Usherwood EJ, Ross A, Dyson H, Nash T. 1998. Lung epithelial cells are a major site of murine gammaherpesvirus persistence. J Exp Med 187:1941–1951. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weck KE, Barkon ML, Yoo LI, Speck SH, Virgin HI. 1996. Mature B cells are required for acute splenic infection, but not for establishment of latency, by murine gammaherpesvirus 68. J Virol 70:6775–6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hwang S, Wu TT, Tong LM, Kim KS, Martinez-Guzman D, Colantonio AD, Uittenbogaart CH, Sun R. 2008. Persistent gammaherpesvirus replication and dynamic interaction with the host in vivo. J Virol 82:12498–12509. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01152-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]