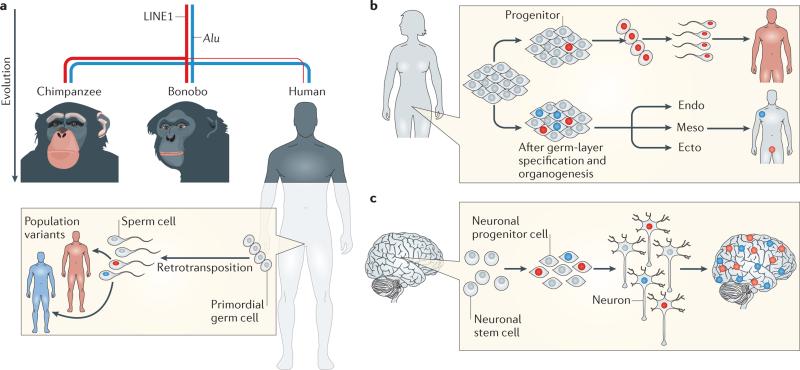

Figure 2. Consequences of germline and somatic retrotransposition events.

a | As humans, chimpanzees and bonobos evolved from a common ancestor, retrotransposons actively mobilized in the ancestral germ lines, which resulted in the generation of genomic variation that natural selection then acted upon. Alu retrotransposition rates (represented by the thickness of the blue line) remained relatively similar between the three species; however, long interspersed nuclear element 1 (LINE1) retrotransposition rates (represented by the thickness of the red line) were suppressed in the human lineage. Retrotransposition of LINE, Alu and SINE–VNTR–Alu (SVA) elements continues to occur in the human germ line, which creates population variants that are present in every cell of an individual’s body and are also passed on to future generations. Whether LINE1 or Alu somatic retrotransposition rates differ between human and non-human primates is unknown. b | Somatic retrotransposition can happen at any time during embryogenesis. Retrotransposition events that occur in early pluripotent progenitor cells will result in somatic mosaicism: these unique cells will contribute to all tissues of the body of the individual, including the germ line. Somatic retrotransposition that happens after germ-layer specification and organogenesis, however, results in germ-layer- or tissue-specific insertions. These will not contribute to the germ line. c | Somatic retrotransposition increases as neural stem cells differentiate into neurons and results in neurons with unique genomes. Variability exists between the rates of retrotransposition and regions in which it occurs between individuals. High rates of retrotransposition events seem to occur in the hippocampus in some individuals22,28. Figure is adapted from Muotri, A. R., Marchetto, M. C., Coufal, N. G. & Gage, F. H. The necessary junk: new functions for transposable elements. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, R159–R167 (2007)80, by permission of Oxford University Press.