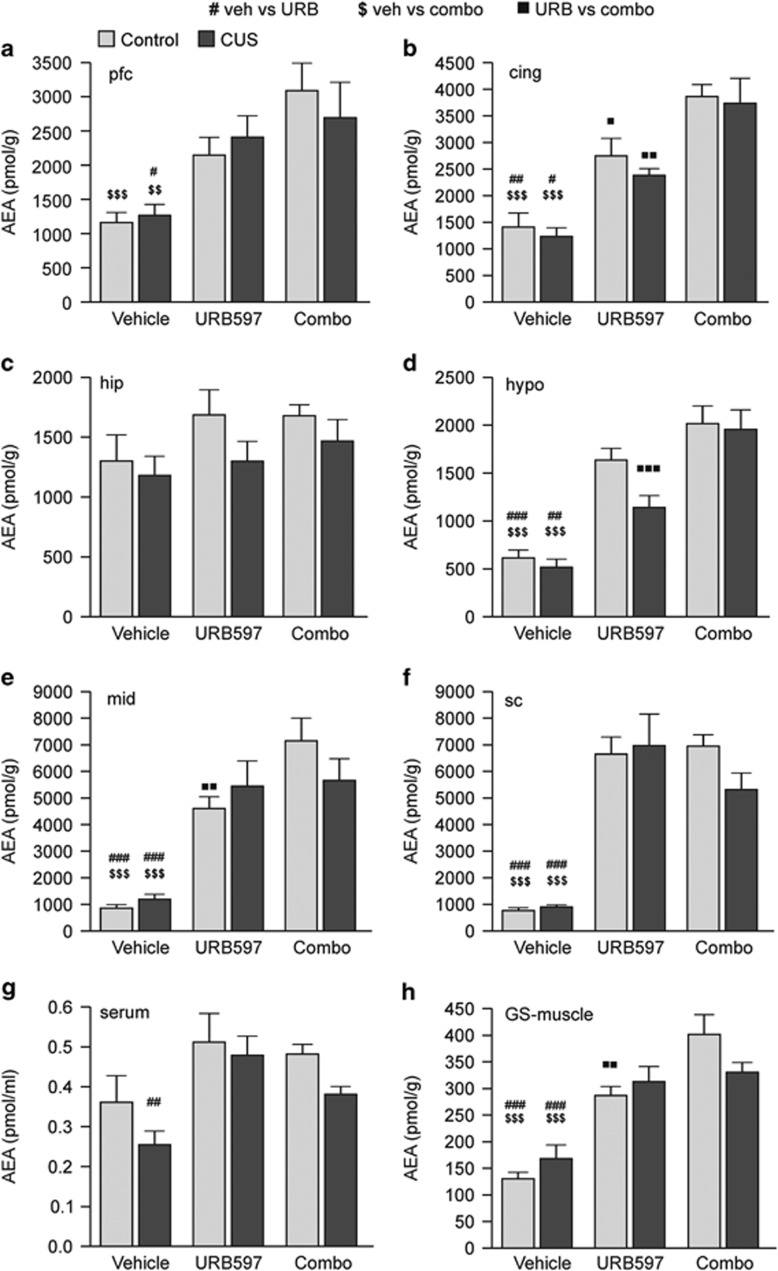

Figure 4.

Quantification of anandamide (AEA) in brain, muscle, and serum by LC-MRM. CUS did not change AEA levels in brain (a–f) and left GS muscle (h), as no difference between vehicle-treated control and CUS mice was found. A non-statistically significant decrease (p=0.2) in AEA level in vehicle-treated CUS mice compared with controls was observed only in serum (g). URB597 treatment induced a ∼2-fold increase in AEA level in cingulate cortex (b), hypothalamus (d) and muscle (h) and a ∼6-fold increase in midbrain (e) and spinal cord (f) and no effect in hippocampus (c) of both animal groups. URB597 also induced a ∼2-fold increase in AEA level in prefrontal cortex (a) and serum (g) but only in CUS mice. Combo treatment induced a statistically significant increase in AEA level compared with vehicle-treated animals in all tissues except hippocampus (c) and serum (g). Compared with URB597-treated mice, combo treatment induced a synergistic increase in AEA level in midbrain (e) and muscle (h) of control mice only and in cingulate cortex (b) of both control and CUS mice. Statistical differences between specific groups are shown on each bar. #, $, p<0.05; ##, $$,

p<0.05; ##, $$, p<0.01; ###, $$$,

p<0.01; ###, $$$, p<0.001, Bonferroni's multiple comparison tests after significant two-way ANOVA; n=8–10 animals in each group. Additional statistical analyses are reported in Table 4. AEA, anandamide; cing, cingulate cortex; hip, hippocampus; hypo, hypothalamus; GS-muscle, gastrocnemius-soleus muscle; mid, midbrain; pfc, prefrontal cortex; sc, spinal cord.

p<0.001, Bonferroni's multiple comparison tests after significant two-way ANOVA; n=8–10 animals in each group. Additional statistical analyses are reported in Table 4. AEA, anandamide; cing, cingulate cortex; hip, hippocampus; hypo, hypothalamus; GS-muscle, gastrocnemius-soleus muscle; mid, midbrain; pfc, prefrontal cortex; sc, spinal cord.