Abstract

Background

This research identifies stressors that correlate with depression, focusing on acculturation, among female Korean immigrants in California.

Methods

Telephone interviews were conducted with female adults of Korean descent (N=592) from a probability sample from 2006 to 2007. 65% of attempted interviews were completed, of which over 90% were conducted in Korean. Analyses include descriptive reports, bivariate correlations, and structural equation modeling.

Results

Findings suggest that acculturation did not have a direct impact on depression and was not associated with social support. However, acculturation was associated with reduced immigrant stress which, in turn, was related to decreased levels of depression. Immigrant stress and social support were the principal direct influences on depression, mediating the effect for most other predictors.

Conclusions

Stressful experiences associated with immigration may induce depressive feelings. Interventions should facilitate acculturation thereby reducing immigrant stress and expand peer networks to increase social support to assuage depression.

Keywords: Korean health, women’s health, acculturation, depression, immigrant stress, social support

INTRODUCTION

International migration is a significant life event in which the language, cultural beliefs, and practices of migrants are distinct from those of the receiving culture. Acculturation-changing of attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to be more consistent with the dominant culture-is one possible mechanism in periods of migration that may strongly influence immigrants’ mental health.

From the stress-health outcome perspective (Holmes and Rahe, 1967), it is possible that acculturation induces depression among immigrant populations as a result of internal stressors and guilt accompanied with the loss of native culture as suggested among Cuban refugees (Rumbaut and Rumbaut, 1976), although this relationship may be less meaningful among non-refugee populations. Acculturation may also reduce depression by providing immigrant populations the means to function in a new culture (Berry and Kim, 1986) by diminishing the impact of stressful experiences as a result of unfamiliarity with the host nation’s culture and increasing instrumental social support by developing a larger peer network. However, empirical knowledge of the effects of acculturation, direct and indirect, on depression among Korean immigrants to the U.S. remains limited (Gomez et al., 2004; Hovey and Magana, 2000; Shin et al., 2005; Turner and Avison, 2003).

The reasons studies have failed to identify the impacts of acculturation on depression are complex but two major problems persist: (1) Reliance upon small convenience samples; and (2) use of models that do not evaluate the independent effect of acculturation on mental health. The aim of the present study is to increase understanding about the pathways by which acculturation affects psychological health by investigating the mediating role of immigration stress and social support on acculturation’s depressive (or not) influence among a population-based probability sample of Korean immigrant women in California, U.S.A..

Depression is a serious mental health problem that can have a detrimental effect on physical health and lifestyle behaviors (Bouhuys et al., 2004). With increases in the size of the U.S. Korean population, studies specific to the mental health of Korean immigrants are beginning to appear (Kim et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2004; Park and Bernstein, 2008). Korean immigrants often report severe depression (Hurh and Kim, 1990; Kuo, 1984; Oh, et al., 2002; Shin, 1993), with rates of depression ranging from 29% to 71% (Lee and Farran, 2004; Pang and Lee, 1994). Moreover, Koreans have a higher prevalence of severe depression than their Asian counterparts of Filipino, Japanese, and Chinese descent (Kuo, 1984).

Acculturation is an important explanatory variable for depression among immigrants (Lee et al., 2004). The lifestyle changes often associated with resettlement in a new country can be emotionally difficult. Stress induced as a direct result of the immigration experience (immigration or acculturative stress) is purported to increase the risk for developing depression (Hurh and Kim, 1990; Oh et al.,, 2002).

For example, a study of 157 Koreans randomly drawn from the “Directory of the Korean Society of Greater Pittsburgh,” reported that language acculturation reduced depression through reduction of acculturative stress (Oh et al., 2002). Unfortunately, the authors constrained the influence of acculturation to two separate constructs, language and cultural acculturation, and evaluated different paths of influence thereby restricting the full range of theoretical possibilities for acculturation’s influence on depression.

The mechanism by which acculturation would influence depression directly is unclear. It is likely that acculturation may increase depression via internal distress as persons lose their native culture with which they have emotive attachment in transition to their new cultural norms (Berry and Kim, 1986; 1997). However, there is little empirical support of this logic (Oh et al. 2002). These expectations lead to the following contradictory hypotheses about the direct and indirect influences of acculturation on depression:

-

H1

The direct effect of acculturation increases depression.

-

H2

The effect of acculturation is mediated by immigrant stress. Acculturation reduces immigrant stress thereby reducing depression.

Researchers have begun to consider the ways social support may buffer the effects of immigration stress on mental health. Social support may facilitate immigrants’ adaptation to the majority population in the host society (Hurh and Kim, 1990; Lee et al., 2004). Indeed, research indicates that emotional and instrumental support from family and friends is critical to immigrants’ adaptation (Portes and Schaufller, 1996; Usita and Blieszner, 2002). On the other hand, acculturated persons may have more contacts than unacculturated persons due to English language and cultural sensitivities facilitating interaction with non-Koreans, thereby increasing the network of social support. As a result greater acculturation would result in increased social support and thereby improved mental health, i.e.. acculturation → social support → improved mental health.

Studies among Korean immigrants provide evidence that social support benefits psychological health. Using data from a non-probability sample of 74 Korean international college students in Pittsburg, U.S. students who experienced severe immigrant stress and who received a high level of social support expressed less mental health symptoms than students with a low level of social support (Lee et al., 2004). Moreover, the buffering effect of social support was found only among students who had a high level of acculturation, although, this peculiar finding may be spurious as a result of the small sample used. Another study of 154 Korean immigrant adults in the U.S. found social support reduced the impact of life stressors on depression (Kim et al., 2005). These expectations lead to the following hypothesis:

-

H3

The effect of acculturation is mediated by social support. Acculturation increases social support thereby reducing depression.

METHODS

To evaluate these hypotheses data were drawn from a 2007 telephone survey of California female adults (18 years of age and older, N=591) of Korean descent conducted by closely supervised, bilingual professional interviewers. The survey instrument was specifically designed to collect data about Korean American women’s health. The instrument was first developed in English and back translated into Korean with the assistance of co-investigators in Seoul, Korea, and co-investigators in the U.S. The English-Korean translation process was repeated to optimize isomorphism between concepts in the languages. Focus groups, lead by a bilingual interview supervisor, who had extensive experience in working with prior Korean study participants, were also involved to insure that the meanings of terminology were accurately rendered in the English to Korean translation. The final instrument was pilot tested and interviews were continuously monitored by the interview supervisor to make repairs if problems arose.

The sample was drawn randomly from telephone numbers associated with persons with Korean surnames that had been purchased from a commercial firm and included listed and unlisted numbers derived from a variety of other sources (e.g., membership lists, subscriptions, warrantee information, etc.). Interviews were conducted with the female Korean adult who had the most recent birthday. After up to seven repeated attempts to contact participants and elimination of ineligible respondents (non-Korean, did not speak Korean or English, businesses) about 65% of eligible persons contacted completed interviews, which compares favorably with surveys of general populations (Curtin et al., 2005). About 90.0% of the interviewers were conducted in Korean according to the participant’s preference. The mean length of interviews was 62 minutes (SD=25, Median=57.5, Skewness=1.59). About 98.5% of respondents were judged by interviewers as having a very high or high level of understanding and 97.9% were evaluated as very cooperative or cooperative. Variation in length of interviews depended on specific behaviors, e.g., smokers and drinkers were asked an additional series of questions that required about 15 minutes. A data monitor reviewed interviews within hours of completion for errors of omission or commission so that repairs could be made. All data were double entered in conversion to electronic files. The sample approximated census demographics for women of Korean descent in California fairly closely although it modestly overrepresented older women and underrepresented younger women.

Measures

Depression

A short version (10 items) of The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, CES-D (Radloff, 1977), developed by Cole and colleagues (2004) was used to measure depressive symptomatology. Values ranged from 0 to 25, (Cronbach’s α=.75). High scores on the CES-D indicate high levels of distress. It does not necessarily mean that the participant has a clinical diagnosis of depression, although for simplicity of presentation we refer to those with higher values as more depressed.

Acculturation

The acculturation scale used in this study was adapted from the Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation to U.S. society scale adapted for telephone administration (Suinn et al., 1987; Suinn et al., 1995). Eleven items were designed to measure aspects of cultural preferences involving language, music, food, and self-identification including how persons identified with the U.S. and Korea, father’s identification, and social linkages including ethnicity of peers and preferred associations.

After conversion to a common metric (z-scores), a principal components analysis was computed. Although two components emerged from the analysis using the customary eigenvalue of 1.0 as a cutoff, a single general dimension explained 82.0% of the common and 50.2% of the total variance among items and was used for the measurement of acculturation in this analysis. Wording of items, item loadings, communalities, and proportion of total variance explained are available in a methodological appendix available upon request [Attached to this manuscript for editorial inspection]. For purposes of analysis, a general acculturation to U.S. society scale was formed by computing the mean of standardized items (Mean=−.07, SD=7.34, Cronbach’s α=.88) after permitting up to four scores to be missing. The natural logarithm of the scale was computed to constrain skewness. Analyses demonstrated that the missing data treatment made no significant difference in conclusions.

Immigrant Stress

The Demands of Immigration Scale is a 22 item index that taps demands related to loss, novelty, language difficulties, occupational adjustment, discrimination, and not feeling at home, originally developed by Aroian and colleagues (1998). Response options for a 4-point scale range from agree strongly (2) to disagree strongly (−2), with non-responses and neither coded as a middle value (0). Items were summed and the mean was calculated. Values greater than zero indicate increased immigration stress (demands), less than zero indicate satisfaction with immigration. The resulting scale ranged from −2.00 to 1.95, (Cronbach’s α=.88).

Social Support

Interpersonal social support was measured using the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) following Cohen and colleagues (1985). The scale consists of 40 true or false items. All items were coded such that 1 indicated presence of support, otherwise 0, so that higher values indicate greater social support. The resulting scale ranged from 0 to 40, (Kuder-Richardson 21=.80).

Covariates

Education, employment outside the home, age, and marital status were measured by self report. Education was indicated by years of total education completed in both Korea and the United States once overlapping educational attainment had been eliminated. Work status was measured by reports of working outside the home (coded 1 for working outside the home, otherwise 0). Age was measured in years. Marital status was coded 1 if currently married or cohabiting, otherwise 0.

Analysis Plan

First, descriptive characteristics of Korean women’s mental health in California were reported. Second, bivariate analyses assessed the correlates of depression, acculturation, immigrant stress, social support and other predictors. Third, path analysis was used to decompose the influence of acculturation on depression (Asher, 1976; Byrne, 2001). This method permitted the allocation of variance to specific sequences of variables in explaining complex paths of variation among the antecedent variable, acculturation, and immigrant stress and social support directly and indirectly influencing depression. As a result, the total influence of acculturation was accounted for and the probable mechanisms were distinguished to evaluate a wider range of theoretical possibilities than previous studies. A model that controlled for immigrant stress to evaluate the impacts of acculturation in a recursive model would have been unable to estimate the true effect of acculturation on depression. Analyses were computed using SPSS (version 14.0) and Amos (version 7.0). All tests were two-tailed with alpha=.05.

RESULTS

About 96.3% of respondents were born in Korea. The average immigrant respondent lived about 17.41 years in the U.S. with values ranging from 1 to 50 years (SD=10.07, Median=16.50, Skewness=.36). A large portion of the sample appeared to have been recent immigrants with 1.9% living in the U.S. less than 1 year, 11.5% less than 5 years, and 34.0% less than 10 years. The mean age of respondents in the sample was 46 years (SD= 14.4), ranging from 18 to 82 years. About 78.0% were married and mean years of formal education in Korea was 12.68 (SD= 4.75) and in the U.S. 2.35 (SD=4.35). About 37.6% of subjects reported working outside the home, as reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample.a

| Variable | Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D | 3.16 | 3.80 | (591) |

| Immigrant Stress | −0.53 | 0.74 | (591) |

| Social Support | 31.28 | 4.81 | (591) |

| Acculturation | 0.00 | 0.6 | (591) |

| Age of respondent | 46.00 | 14.4 | (591) |

| Years resident in Korea | 28.22 | 13.40 | (591) |

| Years resident in U.S. | 17.41 | 10.07 | (591) |

| Years education in Korea | 12.68 | 4.75 | (581) |

| Years education in U.S. | 2.35 | 4.35 | (589) |

| Percent | |||

| Working outside the home | 37.6% | (590) | |

| Born in Korea | 96.3 | (591) | |

| Parents born in Korea | 99.0 | (592) | |

| Interviewed in Korean language | 92.3 | (556) | |

| Married | 78.0 | (587) |

Numbers in cells are percentages or means and standard deviations, and N’s. Income was omitted from the analysis since lightly less than 45% of the sample did not provided family income. About 20.8% stated that they “did not know” their household income, 14.2% refused to answer, and 9.6% failed to provide an answer.

The mean score on the CES-D depression scale was 3.16 (SD=3.80). The sample averaged −.53 (SD=.74) on the immigrant stress scale suggesting that the average respondent viewed their immigration experiences favorably. Korean female immigrations appear to be embedded in strong social support networks. On a scale of 0 to 40 interpersonal social support averaged 31.28 (SD=4.81).

Bivariate Associations

Table 2 displays the Pearson’s correlation matrix among CES-D depression scale, acculturation, immigrant stress, social support, and covariates. According to Table 2, acculturation was negatively related to depression (r=−.119, P<.01). Immigrant stress was positively and more strongly related to depression than was acculturation (r=.231, P<.01), and interpersonal social support was negatively related to depression (r=−.293, P<.01).

Table 2.

Mental Health Correlation Matrix among Korean Women in California, 2007.a

| Indicator | CES-D | Accult. | Imm Stress | Soc Sup. | Education | Work | Married |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CES-D | |||||||

| Acculturation | −.119** | ||||||

| Immigrant Stress | .231** | −.512** | |||||

| Social Support | −.293** | .099* | −.048 | ||||

| Education | −.082* | .174** | −.209** | .143** | |||

| Work | −.011 | .112** | −.159** | .031 | .122** | ||

| Married | −.104* | −.310** | .080 | .014 | .151** | .039 | |

| Age | .170** | −.462** | .214** | −.197** | −.249** | −.070 | .126** |

Numbers in cells are Pearson’s correlation coefficients and two tailed probabilities;

P<.05,

P<.01. Pairwise deletion used for analysis, N=591.

Acculturation was negatively related to immigrant stress (r=−.512, P<.01) and was positively related to interpersonal social support, although the association was modest and not statistically significant (r=.099, P>.05). These findings suggest that acculturation reduces depression but a large portion of this association may be explained by the shared relationships with immigrant stress and social support.

Multivariate Associations

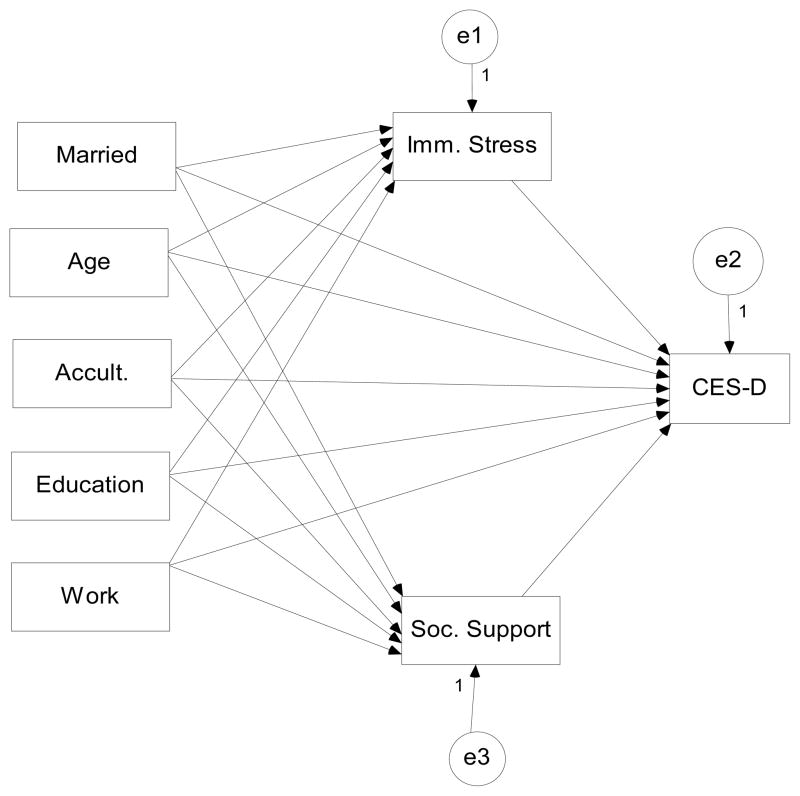

According to hypothesized expectations, acculturation was allowed to have both direct and indirect effects, mediated by immigrant stress and social support, on depression. Education, age, martial status, and working status were also included in the model. In the path model, covariates such as acculturation were allowed to directly influence depression or indirectly influence depression through the mediators, immigrant stress (Berry et al., 1987) and social support (Schulz et al., 2006). Acculturation may reduce depression directly or indirectly by reducing immigrant stress or increasing social support. A graphical representation of this theoretical model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed Path Model of Korean Women’s Depression.a

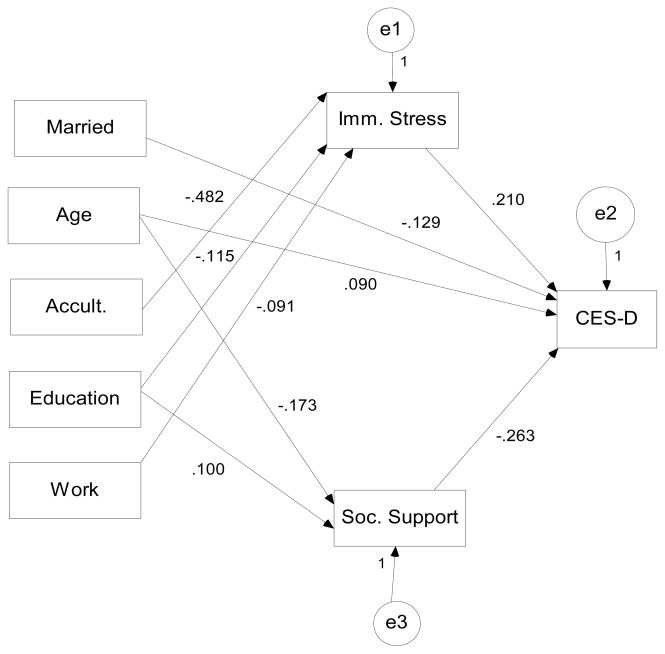

Using this model the mechanisms by which acculturation and other social structures influence depression were evaluated. Following standard procedures (Asher, 1976), a priori paths that were insignificant (P>.05) were deleted after initial calculation. Contrary to hypothesized expectations, acculturation appeared to have no indirect influence on social support and no direct influence on CES-D depression. This suggests that the likely influence of acculturation is mediated by immigrant stress. Marital status and age were not associated with immigrant stress, and working outside the home did not influence interpersonal social support. Education and working outside the home had no direct effect on depression. The revised model detailing standardized regression weights, recomputed after insignificant associations were deleted, is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Observed Path Model of Korean Women’s Depression.a.

aNumbers are standardized regression weights using path analysis after insignificant associations from Figure 1 were deleted and the analysis recomputed. All associations were statistical significance (p<.05). Missing values among observations were imputed using full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML), N=591.

Acculturation (β=−.482), education (β=−.115), and working outside the home (β=−.091) all reduced immigrant stress. Younger age (β=−.173) and education (β=.100) were associated with increased social support. Older Age (β=.090), single status (β=−.129), low social support (β= −.263), and immigrant stress (β=.210) increased depression. The model Chi-Square was 7.344 with 9 degrees of freedom and statistically insignificant (P<.601), suggesting the data accurately fit our theoretical model and no statistically important alternative paths have been excluded. For predictors of depression R2=.154.

Hypothesis testing rests on the direct, indirect, and total influence of acculturation and covariates on depression. Estimates for these were calculated from the identified path model as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Standardized Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects on CES-D among Korean Women in California, 2007.a

| Predictor | Direct | Indirect | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturation | -- | −.101 | −.101 |

| Immigrant Stress | .210 | -- | .210 |

| Social Support | −.263 | -- | −.263 |

| Education | -- | −.050 | −.050 |

| Work | -- | −.019 | −.019 |

| Married | −.129 | -- | −.129 |

| Age | .090 | .046 | .136 |

|

|

|||

| χ(9)=7.344, P<.601; R2=.154 |

Numbers in cells are standardized regression weights using path analysis for the graphic in Figure 2. All associations were statistically significant (p<.05). Missing values among observations were imputed using full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML), N=591;

-- = not calculated.

Acculturation was inversely associated with depression via mediation through immigrant stress (β=−.101). This suggests acculturation is a protective factor for depression by reducing immigrant stress. Higher levels of acculturation were related to lower levels of immigrant stress which was related to lower depression scores. Contrary to previous studies this analysis does not support a mediated influence through social support (Lee et al., 2004) or a direct influence for acculturation on depression. Persons with high social support (β=−.263) and low immigrant stress (β=.210) were less depressed; and these were the most influential predictors of depression.

This analysis clarifies that working outside the home (β=−.019) reduced immigrant stress thereby reducing depression. Part of immigrant stress may be the downward social mobility immigrants face, and employment favors social mobility. On the other hand, the possibility that working increases social support was unfounded in these data, as these concepts were statistically unrelated. Age decreased social support and thereby increased depression (β=.046), suggesting that older persons have less social support, likely a result of peer deaths, for stress relief. Education increased interpersonal social support and decreased immigrant stress thereby reducing depression (β=−.050). It is probable that education provided resources that aided immigrant adaptation that reduced immigrant stress and provide social skills that aid peer relations. Only marriage (β=−.129) and age (β=.090) had a direct effect on depression. Married persons reporting lower levels of depression likely results from spousal support and age may increase depression among immigrants due to significant life events, like health problems.

DISCUSSION

This analysis clarified the mechanisms responsible for how acculturation among the largely immigrant Korean population was associated with depression. The influence of acculturation on depression appeared to be a result of reductions in immigrant stress that then reduced depression. Most often immigrant stress and social support mediated the influence of other predictors on depression.

Previous research concerning immigrants has relied on small convenience samples, limited measures, and weak statistical models to analyze the effects of predictors. Unfortunately, earlier studies did not clarify the protective factors for depression. Our findings provide evidence from a representative probability sample concerning the correlates of depression using a path model designed to capture the estimated influence among predictor variables. Knowledge of these mechanisms and their predictors suggests strategies for mental health interventions among Korean women as well as other immigrant groups.

Interventions targeted at promoting acculturation may reduce depression. Specifically programs that provide English training and develop routines for new life experiences may be implemented to reduce depression. But promoting acculturation might also lead to other health problems – i.e. obesity, smoking, and alcohol use; see Hofstetter and colleagues (2004). Instead, reducing immigrant stress directly by seminars on applying for new credentials and jobs may be more efficacious. In addition, establishment of strong, welcoming institutions that provide interpersonal social support are also likely to reduce depression. A great deal of evidence exists that, for Koreans, the church plays a major role in facilitating accommodation to American culture and developing social support (Kwon et al., 2001). Interventions may wish to target these groupings to enhance the existing level of depressive protection at religious institutions.

Expansion of education and employment may also reduce immigrant stress and promote positive mental health as suggested by our model. One possibility is to target educational programs that may develop resources specific to the demands of immigration promoting greater problem solving abilities. An intervention in this form may accommodate both the positive influences of education and immigrant stress. In addition, if this program included opportunities for peer relations they may also develop social support. The effectiveness of these general interventions and alternatives to reduce depression among Korean immigrants to the U.S. remains to be tested using experimental trials based on rigorous longitudinal analysis

Limitations

The present study was limited by the following: First, data did not allow alternative measures of mental health, especially those related to happiness or satisfaction. The correlates of other mental states may be different than those for depression. Second, this study evaluated the larger constructs that increase depression among the general female Korean immigrant population; however, contemporaneous life events that may increase depression were not measured. The incidence of abuse, death of a close family member, chronic illness, or other stressors may have operated as confounds. But the correlation among these factors and social structures is tenuous and likely close to zero if observable, except for age, which we hypothesized for future investigation. Future studies should test alternative models and explore situational factors that may be associated with depression that were beyond the scope of this study. Third, the influence of interactions between immigrant stress and social support were not explored, but the overall fit of the model suggests that such an interaction would not improve model fit. However, future studies exclusively focused on this interaction may be fruitful. Fourth, data were specific to women since these data were derived from a larger study of Korean women’s health. Generalizations to male populations should be made with caution, since men may encounter different structural factors and these may have different influences on depression.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by award number R01CA105199 from the National Cancer Institute to C. Richard Hofstetter. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Intramural support was received from the Center for Behavioral Epidemiology and Community Health, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, San Diego, California, USA. We wish to thank Heeson Juon (Hopkins), Keith Schnakenberg (SDSU), Jessie Macaulay (UCSD), Tara Beeston (SDSU), and the editor and reviewers of JNMD for helpful comments. Any omissions are purely accidental.

References

- Asher HB. Casual modeling. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Aroian KJ, Norris AE, Tran TV, Schappler-Morris N. Development and psychometric evaluation of the demands of immigration scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 1998;6:175–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Kim U. Acculturation and mental health. In: Dasen PR, Berry JW, Sartorius N, editors. Health and cross-cultural psychology: Toward applications. Newburg Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1986. pp. 207–236. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Kim U, Minde T, Mok D. Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review. 1987;21(3):491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bouhuys AL, Flentge F, Oldehinkel AJ, van den Berg M. Potential psychosocial mechanisms linking depression to immune function in elderly subjects. Psychiatry Research. 2004;127(3):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory, research and application. The Hague, Holland: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cole JC, Rabin AS, Smith TL, Kaufman AS. Development and validation of a Rasch-derived CES-D short form. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:360–372. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. Changes in telephone survey nonresponse over the past quarter century. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2005;69(1):87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez S, Kelsey JL, Glaser SL, Lee MM, Sidney S. Immigration and acculturation in relation to health and health-related risk factors among specific Asian subgroups in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(11):1977–1984. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstetter CR, Hovell MF, Lee J, Zakarian J, Park H, Paik HY, Irvin V. Tobacco use and acculturation among Californians of Korean descent: A behavioral epidemiological analysis. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6(3):481–489. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001696646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD, Magana C. Acculturative stress, anxiety, and depression among Mexican immigrant farm workers in the midwest United States. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2000;2(3):119–131. doi: 10.1023/A:1009556802759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurh WM, Kim KC. Korean immigrants in America: A structural analysis of ethnic confinement and adhesive adaptation. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hurh MH, Kim KC. Correlates of Korean immigrants’ mental health. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1990;178(11):703–711. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MT, Han HR, Shin HS. Factors associated with depression experience of immigrant populations: A study of Korean immigrants. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2005;19(5):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH. The prevalence of depression among Asian Americans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1984;172:449–57. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon VH. Entrepreneurship and Religion: Korean immigrants in Houston, Texas. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EE, Farran CJ. Depression among Korean, Korean American, and Caucasian American family caregivers. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2004;15:18–25. doi: 10.1177/1043659603260010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Koeske GF, Sales E. Social support buffering of acculturative stress: A study of mental health symptoms among Korean international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2004;28:399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Moon A, Knight BG. Depression among elderly Korean immigrants: Exploring socio-cultural factors. Journal of Ethnic, Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2004;13(4):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y, Koeske GF, Sales E. Acculturation, stress, and depression symptoms among Korean immigrants in the United States. Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;142:511–526. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang KY, Lee MH. Prevalence of depression and somatic symptoms among Korean elderly immigrants. Yonsei Medical Journal. 1994;35:155–161. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1994.35.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Bernstein KS. Depression and Korean American immigrants. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2008;22(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Schauffler R. Language and the second generation: Bilingualism yesterday and today. In: Portes A, editor. The second generation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1996. pp. 8–29. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RD, Rumbaut RG. The family in exile: Cuban expatriates in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:395–99. doi: 10.1176/ajp.133.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Zenk SN, Parker EA, Lichtenstein R, Shellman-Weir S, Klem L. Psychosocial stress and social support as mediators of relationships between income, length of residence and depressive symptoms among African American women on Detroit’s eastside. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(2):510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin KR. Factors predicting depression among Korean American women in New York. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005;30(5):415–423. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(93)90051-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, Rickard-Figueroa K, Lew S, Vigil P. The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identity acculturation scale: An initial report. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1987;47:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Suinn RM, Khoo G, Ahuna C. The Suinn-Lew Asian self-identify acculturation scale: Cross-cultural information. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 1995;23:139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Avison WR. Status variations in stress exposure: Implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(4):488–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usita PM, Blieszner R. Communication challenges and intimacy strategies of immigrant mothers and adult daughters. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23(2):266–286. [Google Scholar]

- Yu EY, Choe P, Han SI. Korean population in the United States, 2000: Demographic characteristics and socio-economic status. International Journal of Korean Studies. 2002;6(1):71–107. [Google Scholar]