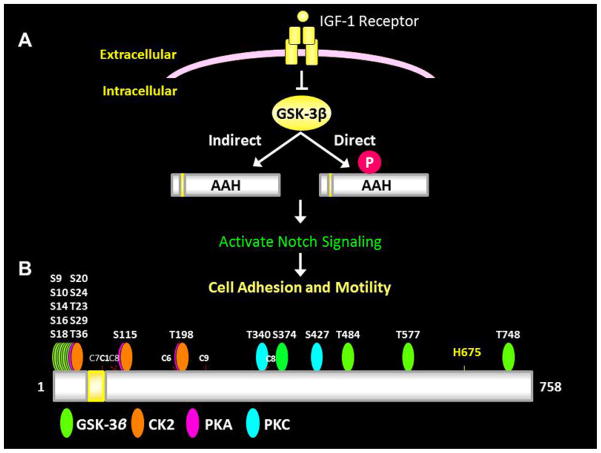

Figure 9.

(A) Diagram of insulin/IGF-1 regulation of AAH. Normally, insulin/IGF-1 stimulation inhibits GSK-3β via upstream PI3K-Akt activation. However, uncoupling or inhibition of signaling can lead to increased GSK-3β activity and phosphorylation of AAH (direct). In addition, oxidative stress levels increase with GSK-3β activation; this response can activate other kinases that phosphorylate AAH (indirect). Depending on the positions and nature of AAH phosphorylation, AAH’s protein levels can either increase (enhanced stability) or decreased (increased cleavage and degradation). With increased levels of AAH protein expression, correspondingly increased AAH catalytic activity hydroxylates Notch, causing it to cleave, i.e. it activates Notch signaling. The Notch intracellular domain then translocates to the nucleus where it promotes transcription of genes that increase cell adhesion, motility, and invasion. (B) Diagram of predicted predicted phosphorylation sites on AAH. Most of sites correspond to GSK-3β and are distributed in the N-terminus of the protein. CK2, PKA, and PKC also can phosphorylate AAH. The H675 residue is critical for catalytic (hydroxylase) activity.