Abstract

S-Adenosylmethionine, abbreviated as SAM, SAMe or AdoMet, is the principal methyl group donor in the mammalian cell and the first step metabolite of the methionine cycle, being synthesized by MAT (methionine adenosyltransferase) from methionine and ATP. About 60 years after its identification, SAMe is admitted as a key hepatic regulator whose level needs to be maintained within a specific range in order to avoid liver damage. Recently, in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated the regulatory role of SAMe in HGF (hepatocyte growth factor)-mediated hepatocyte proliferation through a mechanism that implicates the activation of the non-canonical LKB1/AMPK/eNOS cascade and HuR function. Regarding hepatic differentiation, cellular SAMe content varies depending on the status of the cell, being lower in immature than in adult hepatocytes. This finding suggests a SAMe regulatory effect also in this cellular process, which very recently was reported and related to HuR activity. Although in the last years this and other discoveries contributed to throw light into the tangle of regulatory mechanisms that govern this complex process, an overall understanding is still a challenge. For this purpose, the in vitro hepatic differentiation culture systems by using stem cells or fetal hepatoblasts are considered as valuable tools which, in combination with the methods used in current days to elucidate cell signaling pathways, surely will help to clear up this question.

Keywords: S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe), MAT (methionine adenosyltransferase), HuR, Hepatocyte, Liver, Hepatocyte differentiation, Hepatocyte proliferation, Stem cells

1. Introduction

1.1. Methionine Metabolism, Synthesis of SAMe

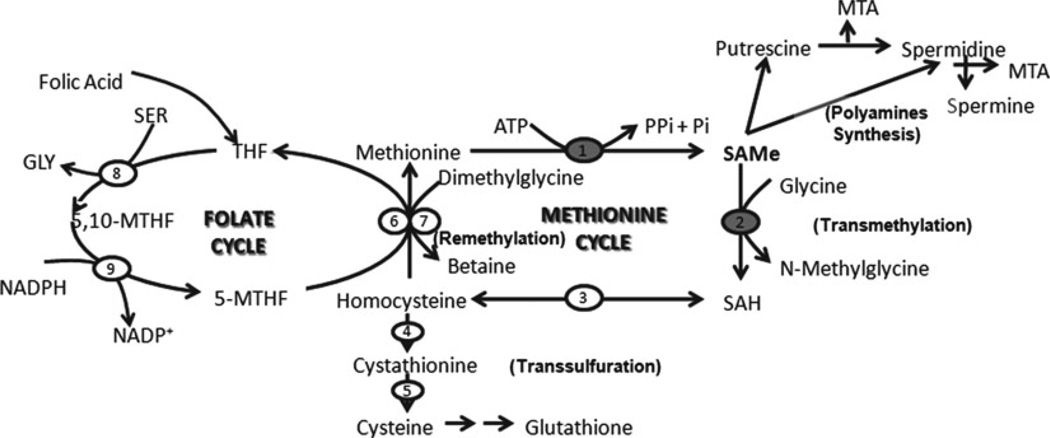

In the early 1950s, Cantoni, completing the studies carried out by Vincent du Vigneaud during 1930s, identified SAMe as the product of the reaction between methionine and ATP (adenosine triphosphate) capable of donating its methyl group to nicotinamide or creatine (1). Several years and studies after this discovery, an integrated concept of the methionine cycle and SAMe as the link between the main metabolic pathways: polyamines synthesis, transsulfuration, transmethylation and folate metabolism, was provided (2) (Fig. 1), emerging SAMe as the major biological donor of methyl groups.

Fig. 1.

Hepatic SAMe metabolism. SAMe is synthesized in the cytosol of every cell. However, SAMe synthesis and utilization occurs mainly in the liver. SAMe is generated from methionine and ATP in a reaction catalyzed by MAT (1). MTA is produced from SAMe through the polyamine biosynthetic pathway, and this compound is metabolized solely by MTA-phosphorylase to yield 5-methylthioribose-1-phosphate and adenine, a crucial step in the methionine and purine salvage pathways, respectively. In transmethylation, SAMe donates its methyl group to a large variety of acceptor molecules in reactions catalyzed by dozens of methyltransferases. The most abundant of these methyltransferases in mammalian liver is GNMT (2). SAH is generated as a product of transmethylation and is hydrolyzed to form homocysteine (Hcy) and adenosine through a reversible reaction catalyzed by SAH hydrolase (3). Hcy lies at the junction of two intersecting pathways: the transsulfuration pathway : In the liver, Hcy forms cysteine via a two-step enzymatic process catalyzed by cystathionineβ-synthase (CBS) (4) and cystathionase (5), which converts the sulfur atom of methionine to cysteine and glutathione; and the remethylation pathway : homocysteine can be remethylated to form methionine by two different enzymes, methionine synthase (MS) (6), and betaine homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT) (7), and is coupled to the folate cycle. In this cycle, tetrahydrofolate (THF) is converted to 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-MTHF) by the enzyme methylene Tetrahydrofolate synthase (8) and then to 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF) by the enzyme methylene Tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) (9).

In mammals, MAT is the sole enzyme that catalyzes the formation of SAMe and the product of two different genes, MAT1A and MAT2A (3). In the adult organism, MAT1A is mainly expressed in the hepatocytes encoding MATI/III enzymes, whereas MAT2A, which codes for MATII, is expressed in all tissues. Because of differences in the regulatory and kinetic properties of the various MAT isoforms, the gene product of MAT1A is more efficient in the synthesis of SAMe than the gene product of MAT2A (4–6). In consequence, although all mammalian cells can synthesize SAMe, the liver is the principal organ for conversion of dietary methionine into SAMe and where up to 85% of all transmethylation reactions occur (7).

1.2. SAMe in Liver Pathogenesis

The effect the alteration of methionine metabolism and, in consequence, of cellular SAMe content, has on liver pathophysiology was discovered several decades ago. In 1932, Best’s group demonstrated that rats fed with a diet deficient in methyl groups, such as methionine and choline, spontaneously develop liver steatosis (fatty liver) within a few weeks (8). In case the diet continues, rats progressively develop NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; inflamed fatty liver), fibrosis, cirrhosis and, in some cases, HCC (hepatocellular carcinoma) (9). In humans, cirrhotic patients showed impairment in SAMe biosynthesis as a result of decreased expression of MAT1A and MAT hepatic activity (10), resulting on low levels of GSH (glutathione). After SAMe administration, the level of GSH was increased (11), as well as the survival of patients (12).

However, not only the deficiency in hepatic SAMe biosynthesis leads to liver injury, but also abnormally increased methionine and SAMe contents. Patients with mutated GNMT (glycine N-methyltransferase) gene, which encodes the main methyltransferase responsible for the catabolism of SAMe excess (13), also develop steatosis, fibrosis and HCC (14). Moreover, a GNMT polymorphism (1289C > T) has been associated with HCC (15).

These findings regarding the importance of maintaining hepatic SAMe content within a specific range, are supported by those observed in mice lacking MAT1A and GNMT, with low and high levels of SAMe, respectively. Both groups of knockout mice successfully mimic the underlying pathologies observed in humans, spontaneously developing NASH and finally HCC, and in the case of GNMT−/− mice, fibrosis as well (14, 16). Although the expression of the pathology slightly differs among both groups of mice, a high susceptibility to damage induced by hepatotoxic agents and an impaired liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy are shared (17–19) supporting the key role of SAMe in the normal function of the liver.

2. Role of SAMe in Hepatocyte Proliferation

As the myth of Prometheus revealed, the high proliferative capacity of the liver after an injury is known since ancient Greeks times (20). In the bench, the best experimental model for the study of liver regeneration is partial hepatectomy (PH), the surgical removal of two-thirds of the liver tissue reported in rats by Higgins and Anderson (21). After PH, the regeneration of the liver is carried out by proliferation of the mature parenchymal cell populations, including hepatocytes, which divide once or twice to restore the original organ mass, without stem cell involvement (20, 22), a fact that raises this technique to the most often used stimulus to study the mechanisms involved in mature hepatocyte proliferation in vivo.

A large number of genes are involved in the complex cellular response, which allows liver regeneration, including cytokines and growth and metabolic factors. Among implicated hepatic mitogenic factors, one of the most important is HGF, secreted by mesenchymal cells. In rats, within 1 h after PH, the plasma level of HGF is increased more than 20-fold (23) and about 2 h later iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase) expression and NO (nitric oxide) biosynthesis are induced (24). NO reduces SAMe levels by specifically inhibiting MAT through S-nitrosylation of cysteine residue121 (25–27). These events lead hepatocytes into DNA synthesis and induction of early-response genes, as the first step for regeneration (27, 28).

Accumulating evidence indicates a key role of SAMe in hepatic growth. The administration of exogenous SAMe after PH prevents the reduction on cellular SAMe content and the DNA synthesis is inhibited, blocking the progression of regeneration (5). In rats previously treated with hepatocarcinogen, SAMe supplementation prevents the development of HCC (29) and, in cultured hepatocytes, is able to block the mitogenic effect of HGF (30). In addition, in MAT1A knockout mice, SAMe deficiency leads to uncontrolled hepatocyte proliferation (16), whereas in GNMT deficient mice, elevated levels of hepatic SAMe causes impaired liver regeneration after PH (19). The mechanism underlying the effect of SAMe content variation in the proliferation of hepatocytes was elucidated in the last years.

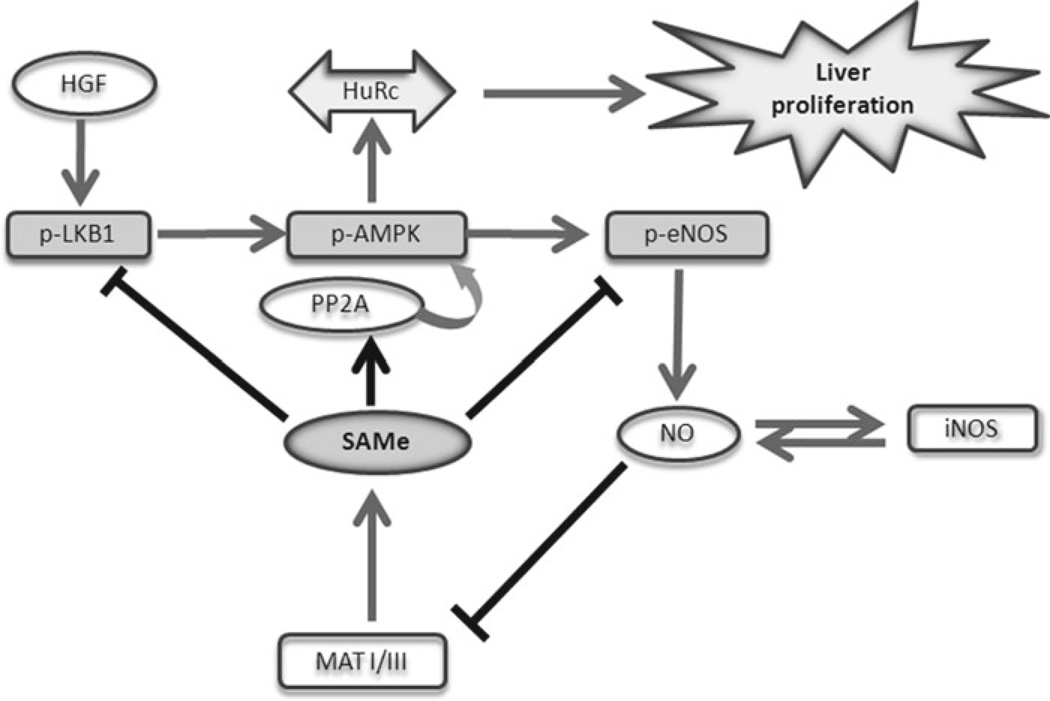

The proliferative response promoted by HGF includes the activation of four signaling pathways; Ras/ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase)/MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), PI3K/Akt, Rac/Pak and Crk/Rap1 (30, 31). Recently, the activation of an alternative noncanonical LKB1/AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase)/eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase) cascade has been reported (32). AMPK, a Serine/Threonine kinase involved in responding to cellular stresses by inhibiting cellular processes that consume energy and activating catabolic pathways that generate ATP (33), was also reported to regulate the subcellular localization of HuR (Human antigen R), an ubiquitously expressed RNA-binding protein (RBP) that increases the stability of target mRNAs (34). In hepatocytes, the activation of AMPK after HGF stimulus promotes the translocation from the nucleus to the cytosol of HuR, which stabilizes several cell-cycle genes such as cyclin A2 and D1, allowing the hepatocytes to proliferate (35). SAMe is able to prevent this process by inhibiting the phosphorylation of AMPK through a mechanism that likely involves the methylation of PP2A (protein phosphatase 2A) and its association to AMPK (35). In consequence, HuR is not transported to the cytoplasm and the stabilization of target genes does not occur, blocking HGF-induced proliferative response. A schematic representation of SAMe-regulated LKB1/AMPK/eNOS cascade and HuR involvement in HGF-induced hepatic growth is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Outline of the LKB1/AMPK/eNOS cascade. HGF induces the phosphorylation and activation of LKB1, AMPK and eNOS. AMPK phosphorylation induces the translocation to cytoplasm of HuR (HuRc), an RNA-binding protein that induces cell-cycle progression and hepatocyte proliferation by increasing the half-life of target mRNAs such as cyclin A2 and cyclin D1. eNOS-dependent NO production activates iNOS induction, which further contributes to NO synthesis, and methionine adenosyltransferase I/III (MAT I/III) inactivation, the main enzyme responsible for hepatic SAMe synthesis. This reduction in hepatic SAMe synthesis prevents the methylation and activation of PP2A, which further stimulates the phosphorylation and activation of the LKB1/AMPK/eNOS cascade and hepatocyte proliferation. SAMe treatment inhibits HGF-mediated hepatocyte proliferation via stimulation of PP2A methylation and inactivation of LKB1 and AMPK.

3. Human Antigen R

In recent years, messenger RNA (mRNA) turnover has emerged as a posttranscriptional mechanism that critically contributes to regulate the gene expression pattern during different cellular processes (36–38). One of the major actors in this scenario is HuR, the ubiquitously expressed member of the Hu/Elav family of RBPs (39). All family members contain three RNA recognition motifs (RRM) with high affinity for adenines and uracils-rich elements (AU-rich elements or AREs) (40), usually found in the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of labile mRNAs (41). As consequence of this selective binding, HuR stabilizes target mRNAs, increasing their half-life and/or translation. Other identified RBPs promote labile mRNA decay, such as AUF1, TTP (Tristetraprolin) and KSRP (KH-type splicing regulatory protein) (42).

The regulation of HuR function, like other RBPs, appears to be closely linked to its subcellular localization (43). HuR is predominantly (>90%) nuclear, but can be exported to the cytoplasm in response to a variety of agents, notably proliferative and stressful signals (44, 45), by a process that involves a nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling domain (HNS), located in the hinge region between RRMs 2 and 3 (46), and its association with transport receptors such as CRM1 and Transportins 1 and 2 (TRN1 and 2) (47, 48). Although not fully resolved, HuR may initially bind target mRNAs in the nucleus and transport them into the cytoplasm, avoiding mRNA decay by inhibiting the de-adenylation and targeting to the exosome of the transcripts or by competing for binding sites with destabilizing RBPs that recognize AREs (37).

Among HuR target mRNAs described to date, are those encoding genes implicated in cellular processes such as proliferation (32), apoptosis (49) or inflammation (50). Regarding cellular differentiation process, HuR is known to have a putative role in the differentiation of specific cellular lineages, such as spermatocytes (51), myocytes (52, 53) and adipocytes (54). These studies show a predominantly nuclear localization of HuR in actively proliferating, undifferentiated cells, but strikingly abundant in the cytoplasm upon induction and duration of differentiation, returning to a nuclear presence upon the completion of cell differentiation process.

The precise mechanism underlying the stabilization of labile mRNAs by HuR is still not well understood. However, it was suggested that posttranslational modification of HuR critically influences this process (55). Up to now, this RBP was reported to be posttranslationally regulated by phosphorylation at different serine/threonine residues by protein kinases such as cell-cycle checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2) (56) and cyclin dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) (57) and by methylation by coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1 or PRMT4), which specifically transfers the methyl group from SAMe to arginine 217 residue in HuR protein (58). Although the exact effect each posttranslational modification has in HuR behavior has to be investigated individually, in general terms they affect HuR’s mRNA-stabilizing activity by altering its subcellular levels and/or influencing its ability to bind RNA.

4. SAMe and Hepatic Differentiation

In fetal liver, MAT2A expression predominates and is progressively replaced by MAT1A expression throughout liver development, reaching a minimum in the adult hepatocyte, the opposite process occurs during malignant transformation (Fig. 3) (59, 60). Consequently, and because of differences in MAT isozymes properties (4–6), the level of SAMe is higher in mature hepatocytes than in not completely differentiated cells, which suggest a role of SAMe in the developmental process of the liver.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of MAT2A, MAT1A and their posttranslational regulators HuR, methylated-HuR and AUF1 behavior during development, de-differentiation and malignant transformation of hepatocytes. Mature hepatocytes have high expression levels of MAT1A and low AUF1 levels, while MAT2A is present in only very limited amounts due to the activity of its negative regulator, methylated-HuR. During the de-differentiation process, the levels of AUF1 mRNA in hepatocytes increase, the ratio of methylated-HuR/HuR decrease, and as a consequence, there is a switch from MAT1A to MAT2A mRNA production. SAMe treatment of hepatocytes prevents these changes and maintains consistent levels of the RNA-binding proteins and MAT1A expression. During malignant transformation of the hepatocytes, a similar pattern of expression of AUF1, HuR and methylated-HuR, and MAT1A and MAT2A are observed. During liver development, the opposite is observed, and there is a decrease in AUF1 levels and an increase in the methylated-HuR/HuR ratio.

It is known that primary hepatocytes de-differentiate, lose their hepatic polarity upon isolation and rapidly decline in liver-specific functions over culture time. At the same time, MAT1A expression progressively decreases, while MAT2A expression is induced (61). This switch is prevented by exogenous administration of SAMe to the culture medium, maintaining for longer time the differentiated status of the hepatocytes (61), through a mechanism that likely involves delaying the culture-induced expression of proteins expressed by early progenitor cells in the liver, such as Cx43 (conexin 43), and preventing the culture-induced decline of proteins related to mature hepatocytes such as Cx32 (conexin 32) and albumin (unpublished data). These findings identify SAMe as a molecule that differentially regulates gene expression and helps to maintain the functional and differentiated stage of the liver. This concept is further supported by the chemopreventive effects of SAMe exogenous administration on the development of preneoplastic lesions and HCC in models of rat liver carcinogenesis (62).

Studies recently assessed in proliferative and de-differentiated rat hepatocytes, as well as in human HCC samples, demonstrated that the switch in MAT1A/MAT2A expression is due to the posttranscriptional regulation executed on MAT1A and MAT2A by AUF1, HuR and methyl-HuR (59). In poorly differentiated hepatocytes HuR associates with the MAT2A 3' UTR, enhancing its mRNA stability and steady-state levels, whereas AUF1 associates with the MAT1A 3' UTR decreasing its mRNA stability and steady-state abundance. On the other hand, in well-differentiated hepatocytes, methyl-HuR was described for the first time as a destabilizer of MAT2A mRNA (59) (Fig. 3).

As happens in hepatic proliferation, this SAMe/HuR feedback regulation activity could be done through a mechanism involving the activation of AMPK. However, other signaling pathways have been reported to control nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of HuR, such as p38-MAPK, MAPKAPK-2 (MK2) and protein kinase c (PKC) (49), and the list is steadily growing. Moreover, SAMe, as the main cellular methyl group donor, is able to donate its methyl group to a large variety of acceptor molecules including DNA and RNA nucleic acids, phospholipids and proteins, greatly expanding the range of possibilities.

5. Usefulness of In Vitro Hepatic Differentiation Models to Elucidate the Regulatory Role of SAMe and HuR in Hepatocyte Differentiation

In order to uncover the underlying mechanisms by which SAMe level governs the hepatic differentiating program, an exhaustive study in hepatocytes at different maturation stages should be done. However, the difficulty of in vivo carrying out of some of the necessary experiments to clarify the proposed approach, such as silencing or overexpressing the hypothetically involved molecule, makes essential to find an appropriate in vitro model. The most important advantage of working with in vitro culture systems is the possibility to chemically interfere with the cellular process of interest and study the consequences, which lead us to refute or rule out the proposed hypothesis. Owing to the fact that HGF is a potent mitogen not only in vivo but also for hepatocytes in culture (20), the process of hepatic proliferation induced after PH can be easily reproduced in vitro by the addition of this growth factor in the culture medium, which has meant an important step forward in the study of liver regeneration.

Regarding the hepatic developmental process, recapitulating in culture the program in vivo seems to be more difficult. Although the implication of several pathways has been elucidated (63, 64), the overall understanding of their synchronicity and complementarity is still limited, mainly because of the lack of a suitable model. In the last years, this biological event was tried to be efficiently reproduced by priming embryonic stem cells (65, 66), mesenchymal stem cells (67–69), liver progenitor cells (70–72) or, more recently, induced-pluripotent stem cells (73, 74) towards a hepatocyte lineage and/or complete hepatocyte maturation by different combinations of growth factors and matrixes. However, most methods resulted in a heterogeneous cell population or low yields of cells of interest, which leads to dismiss them as reliable models. The interest in defining an efficient device that enables the specific hepatic fate of stem/progenitor cells is based not only on the usefulness for studying the molecular basis of hepatocyte differentiation per se but also on its potential to provide a continual source of liver cells for therapeutic and pharmaco-toxicological purposes (75). In consequence, references in this field increase and are renewed constantly. Although to date the description of a highly productive and standardized experimental protocol is still a challenge, recently, as show several chapters in this book, improvements in the culture conditions have been reported to produce a higher purity of functional hepatocyte-like cells (76). Therefore, new insights on the understanding of how hepatogenesis is controlled can be expected to appear in the near future.

6. General Methodology to Uncover Signaling Cascades with SAMe as Key Regulator

The usual methodology to unmasking the mechanism that modulates a specific cellular program starts with the identification and analysis of the proteins that are part of the signaling pathway triggered or regulated by specific physiological conditions or by the action of a concrete stimulus. According to the hypothesis argued in this chapter, SAMe would act as a regulatory agent of the hepatic developmental process. Therefore, interfering the cellular SAMe content should cause changes in the intracellular signaling cascade, in turn modifying the normal differentiation program. Those changes are key clues to elucidate the constituents of the signaling pathway of interest. After identifying those proteins, the hypothetical tangle of intracellular signaling events must be validated. The usual method consists on reducing or increasing the function of a chosen protein by gene silencing and gene overexpression, respectively, and checking how this alteration affects the subsequent downstream cascade by using techniques such as western blotting. Moreover, considering that SAMe acts as a regulator of HuR functionality, which entails its translocation to the cytosol and stabilization of target mRNAs, a verification of HuR location and functionality would be necessary. Furthermore, taking into consideration that the products of HuR target mRNAs are finally the executors of the cellular response, the identification of those targets in each stage of the hepatic developmental process would help to widen the understanding of this complex program and to complete the succession of intracellular reactions which make the cell capable of differentiating.

The different techniques that make up this methodology are briefly described in the sections below.

6.1. How to Alter Cellular SAMe Content In Vitro

There are two methods to mimic the depletion of cellular SAMe level causes on normal cell behavior. One method involves culturing the cells in culture medium without methionine, precursor of SAMe (77). The other method uses a reagent of analytical grade obtained from commercial sources, cycloleucine. Cycloleucine (1-aminocyclopentane-1-carboxylic acid) is a non-metabolizable synthetic amino acid that competitively inhibits MAT resulting in the blockade of SAMe synthesis (78). Its addition to the culture medium has been reported to cause neither cytotoxicity nor loss of cell viability to primary hepatocytes (79), two key points to take into account when treating cells with synthetic agents. The dosage to use depends on the percentage of SAMe depletion required for the study. A high concentration of cycloleucine, 20 mM, in the culture medium produces an 80% loss of SAMe content 24 h after the treatment (78), while a concentration of 5 mM results in an approximate 50% fall (79). On the other hand, the consequences the increase in cellular SAMe content has in the succession of intracellular events of interest are evaluated by the addition of commercially available SAMe to the culture medium at a high final concentration of 4 mM, due to its low permeability (35). In both cases, to verify the success of the treatment, cellular SAMe content is analyzed by LC/MS (liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry) using an ACQUITY-UPLC system coupled to a LCT Premier Mass Spectrometer equipped with a spray ionization source (14, 61).

6.2. Western/Protein Blotting to Detect HuR and Other Proteins

This technique allows the detection, measurement and characterization of certain proteins from a wide range of sample types and the comparison for protein content between samples from different origins (80). The protein sample to be analyzed can be obtained both from whole-cell lysates and from subcellular fractions. Therefore, this method not only enables to detect the global effects of cellular SAMe content at protein level but also determine the subcellular localization of HuR (35). Proteins are eletrophoretically separated using an SDS polyacrylamide gel according to their molecular weight and subsequently transferred and immobilized on Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) or nitrocellulose membranes before detection by using specific ligands such as polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies. Among the wide range of commercially available antibodies, some of them have been developed against the consensus phosphorylated peptide sequences of specific kinases whose activation depends on phosphorylation, such as AMPK (32, 35), in order to provide a precise measure of enzyme activation. Then, blots are developed by enhanced chemoluminiscence and exposed to x-ray film. Finally, the semi-quantitative analysis of protein level between samples is evaluated through densitometry of blots, which requires digitalization of x-ray films and translation of protein bands intensity in the resulting images into values that subsequently can be presented as graphs (81).

6.3. Immunofluorescence for HuR Subcellular Detection

Another method to visualize the subcellular localization of a protein, in our case, endogenous HuR is performing immunofluorescence assay (35). Cells, plated and cultured onto round cover slips, are fixed in cold methanol followed by blocking of the unspecific binding sites and membrane permeabilization. Next, cells are incubated with the specific antibody against HuR and then with the corresponding secondary antibody conjugated with a fluorochrome such as FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate). Nuclei visualization is done by using fluorescent dyes that selectively bind to double stranded DNA, usually DAPI (diamidino-2-phenylindole) and Hoechst 33342, the latter with a lower photostability. Finally, the cell samples are mounted using commercially available mounting solutions and immune complexes detected by fluorescence or confocal microscopy at an excitation wavelength dependent on the chosen fluorochrome.

6.4. How to Modify Gene Expression

Once the proteins that make up the signaling pathways regulated by SAMe have been identified, the precise flux of intracellular events must be checked and verified. In the last decades, significant advances have been made in understanding the fundamental principles that govern the process by which a gene is translated into a functional protein. Consequently, the ability of a gene to express biologically active proteins can be controlled on the bench.

6.4.1. Gene Silencing

Gene silencing is the term used to describe the mechanism to inhibit the expression of a gene. In our studies, we used the RNAi (RNA interference) technique, which has been demonstrated as a valuable method for posttranscriptional silencing studies (82), to repress at the mRNA level the expression of the proteins LKB1, AMPK and eNOS (32) and HuR (59) in order to uncover the molecular pathway controlled by SAMe in hepatic proliferation and differentiation processes, respectively. We selected the hepatocyte cell line (MLP29), plated 24 h before, to be transfected with the exogenous siRNA (small interfering RNA) using a cationic liposome-based reagent that provides high transfection efficiency and high levels of transgene expression. 24–72 h later, the target mRNA knockdown level is checked by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and the protein knockdown level verified by western/protein blotting. In each experiment, one of the members of the signaling cascade of study was inhibited and the downstream events analyzed by western blotting and compared to those observed in negative control samples.

6.4.2. Gene Overexpression

Gene overexpression is the term used to describe the technique developed to increase the expression of a gene. The usual method followed for this purpose relies on the fact that exogenous DNA containing fragments of a specific gene is randomly inserted into the genome of the transfected cells and transiently expressed, increasing the expression level of that gene and, consequently, its corresponding functional protein. We followed this method to overexpress the RNA-binding recognition domain of HuR, the nucleotide sequence responsible for its function (59). For that, hepatic cells were transfected with a DNA plasmid containing the selected nucleotide sequence and GFP (green fluorescent protein) gene by using the same liposome-based transfection reagent mentioned above. After 4–16 h the complexes were removed. The overexpression of the targeted gene and protein is checked by quantitative RT-PCR and western blotting, respectively. The effects in the downstream intracellular events were also checked by immunoblotting.

6.5. Chemical Inhibitors and Activators

Apart from RNAi, another way to get the functional inactivation of a single gene to clarify the downstream events is the use of specific cell-permeant chemical inhibitors. The key point of this technique is to achieve a selective inhibition, without causing toxicity or alteration in the cell viability and without affecting the normal functionality of secondary molecules, which could tangle the biological response to the drug. Therefore, it is necessary to choose an inhibitor with a well-understood role and competitive inhibitory effect. Nowadays, many inhibitors available on the market have been extensively used and reported as highly specific drugs, such as the MEK inhibitor PD098059 (83, 84) or PI3kinase inhibitor LY294002 (85, 86), arising as extremely powerful tools for analyzing signal transduction processes.

The opposite effect, the activation of a target enzyme, is also easily reproducible in vitro by using specific activators. For instance, in our study focused on elucidating the role of AMPK phosphorylation in the translocation of HuR from the nucleus to the cytosol, for AMPK specific activation we used AICAR (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamideriboside), the most widely used pharmacologic activator of this kinase, at a final concentration of 2 mM (35).

6.6. Detection of RNA Bound to HuR by RNP-Ip

RNP-Ip is the method which enables the immunoprecipitation of HuR using the antigen–antibody reaction principle and the collection of subsets of mRNAs bound to it for further identification by genomic array technology or RT-qPCR (87). Apart from being useful to identify HuR target mRNAs, this method complements the information obtained by performing the immunofluorescence assay, allowing us to verify the functionality of HuR in the cell system. In our studies, for endogenous mRNA-HuR complexes isolation, the whole cell lysate is incubated with Protein A-Sepharose beads previously coated with a specific antibody against HuR and treated with RNase-free DNAse I. After phenol extraction, RNA is precipitated with ethanol containing a blue dye covalently linked to glycogen that coprecipitates with the RNA to facilitate its visualization and recovery. Finally, the collected subsets of mRNA are retrotranscribed for further identification by genomic array technology or, in case of an already identified target mRNA, for expression analysis by quantitative PCR (35, 59).

6.7. Validation/Confirmation of HuR target mRNA: Biotin Pull Down

This in vitro technique permits to validate the interaction between a specific mRNA sequence and an RBP, such as HuR, as well as to know the specific sequence region where the binding occurs. Our team carried out this method to test the possibility that MAT2A and MAT1A mRNAs were targets of HuR and AUF1, respectively (59). It starts with the synthesis of biotinylated transcripts corresponding to the mRNA of interest. For that purpose, total RNA of cultured hepatic cells is collected, reverse-transcribed into cDNA and amplified by PCR using specific primers for different overlap fragments of the target genes, called probes, and 5' oligonucleotides containing the T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence. Next, the PCR products are purified and used as template for the synthesis of the corresponding biotinylated RNA using T7 RNA polymerase and biotin-CTP (cytidine triphosphate). Then, the biotinylated probe is purified and incubated with the protein cell lysate to analyze in the presence of RNase inhibitor. Finally, RNA-HuR complexes are isolated using streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads and analyzed by western blotting using a specific antibody that recognizes HuR. If the probe interacts with HuR it might be in the complex beads-probe-protein and, therefore, detected in the blot.

7. Summary and Conclusions

Hepatic differentiation is a complex process that requires the balanced regulation of multiple pathways. Although significant advances have been made in understanding the molecular mechanisms that modulate the onset of hepatogenesis, the overall understanding is still unclear. SAMe, the main methyl group donor in the cell, since its discovery, has emerged as a key molecule that plays a central role in numerous hepatic processes. Its regulatory effect in the proliferative response of hepatocytes involves the activation of LKB1/AMPK/eNOS cascade and HuR function. Recently, SAMe and HuR were also reported to execute a modulation on the hepatic differentiation program. In order to deeply examine the functioning and regulation of both molecules and unravel the signaling pathways implicated, the utilization of in vitro models that can reproduce physiological events related to hepatocyte differentiation is worthwhile. Although a highly effective and reproducible culture system that triggers stem/progenitor cells into functional hepatocytes is still a challenge, a satisfactory progress in this field has been made in the last years, as show several chapters included in this book, representing an attractive approach for studying the implication of SAMe and HuR in liver development.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by AT-1576 (to JMM and MLM–C), SAF2005-00855, HEPADIP-EULSHM-CT-205, and ETORTEK-2008 (to JMM and MLM–C); Program Ramón y Cajal del MEC and Fundación “La Caixa” (to MLM–C); and Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

References

- 1.Cantoni GL. Biological methylation: selected aspects. Annu Rev Biochem. 1975;44:435–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.44.070175.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelstein JD, Martin JJ. Methionine metabolism in mammals. Distribution of homocysteine between competing pathways. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9508–9513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mato JM, Alvarez L, Ortiz P, et al. S-adenosylmethionine synthesis: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;73:265–280. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mato JM, Corrales FJ, Lu SC, et al. S-adenosylmethionine: a control switch that regulates liver function. FASEB J. 2002;16:15–26. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0401rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mato JM, Lu SC. Role of S-adenosyll-methionine in liver health and injury. Hepatol. 2007;45:1306–1312. doi: 10.1002/hep.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai J, Mao Z, Hwang JJ, et al. Differential expression of methionine adenosyltransferase genes influences the rate of growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1444–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mudd SH, Poole JR. Labile methyl balances for normal humans on various dietary regimens. Metabol. 1975;24:721–735. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(75)90040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Best CH, Hershey JM, Huntsman ME. The effect of lecithin on fat deposition in the liver of the normal rat. J Physiol. 1932;75:56–66. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1932.sp002875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shivapurkar N, Poirier LA. Tissue levels of S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosyl homocysteine in rats fed methyl-deficient, amino acid-defined diets for one to five weeks. Carcinogenesis. 1983;4:1051–1157. doi: 10.1093/carcin/4.8.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duce AM, Ortiz P, Cabrero C, et al. S-Adenosyl-L-methionine synthetase and phospholipid methyltransferase are inhibited in human cirrhosis. Hepatol. 1988;8:65–68. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vendemiale G, Altomare E, Trizio T, et al. Effect of oral S-adenosyl-L-methionine on hepatic glutathione in patients with liver disease. Stand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:407–415. doi: 10.3109/00365528909093067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mato JM, Cámara J, Fernández de Paz J, et al. S-adenosylmethionine in alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial. Hepatol. 1999;30:1081–1089. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mudd SH, Brosnan JT, Brosnan ME, et al. Methyl balance and transmethylation fluxes in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:19–25. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-Chantar ML, Vázquez-Chantada M, Ariz U, et al. Loss of the glycine N-methyltransferase gene leads to steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatol. 2008;47:1191–1199. doi: 10.1002/hep.22159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tseng TL, Shih YP, Huang YC, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of a putative tumor susceptibility gene, GNMT, in liver cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:647–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez-Chantar ML, Corrales FJ, Martinez-Cruz LA, et al. Spontaneous oxidative stress and liver tumors in mice lacking methionine adenosyltransferase 1A. FASEB J. 2002;16:1292–1294. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0078fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu SC, Alvarez L, Huang ZZ, et al. Methionine adenosyltransferase1A knockout mice are predisposed to liver injury and exhibit increased expression of genes involved in proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5560–5565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091016398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Zeng Y, Yang H, et al. Impaired liver regeneration in mice lacking methionine adenosyltransferase 1A. FASEB J. 2004;18:914–916. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1204fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varela-Rey M, Fernández-Ramos D, Martínez-López N, et al. Impaired liver regeneration in mice lacking glycine N-methyltransferase. Hepatol. 2009;50:443–452. doi: 10.1002/hep.23033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalopoulos GK, DeFrances MC. Liver regeneration. Science. 1997;276:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins GM, Anderson RM. Experimental pathology of the liver. I. Restoration of the liver of the white rat following partial surgical removal. Arch Pathol. 1931;12:186–202. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fausto N, Campbell JS, Riehle KJ. Liver regeneration. Hepatol. 2006;43(2 Suppl 1):S45–S53. doi: 10.1002/hep.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindroos PM, Zarnegar R, Michalopoulos GK. Hepatocyte growth factor (hepatopoietin A) rapidly increases in plasma before DNA synthesis and liver regeneration stimulated by partial hepatectomy and carbon tetrachloride administration. Hepatol. 1991;13:743–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hortelano S, Dewez B, Genaro AM, et al. Nitric oxide is released in regenerating liver after partial hepatectomy. Hepatol. 1995;21:776–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruiz F, Corrales FJ, Miqueo C, et al. Nitric oxide inactivates rat hepatic methionine adenosyltransferase In vivo by S-nitrosylation. Hepatol. 1998;28:1051–1057. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pérez-Mato I, Castro C, Ruiz FA, et al. Methionine adenosyltransferase S-nitrosylation is regulated by the basic and acidic amino acids surrounding the target thiol. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17075–17079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Trevijano ER, Martinez-Chantar ML, Latasa MU, et al. NO sensitizes rat hepatocytes to proliferation by modifying S-adenosylmethionine levels. Gastroenterol. 2002;122:1355–1363. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang ZZ, Mao Z, Cai J, et al. Changes in methionine adenosyltransferase during liver regeneration in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G14–G21. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.1.G14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pascale RM, Simile MM, De Miglio MR, et al. Chemoprevention by S-adenosyl-L-methionine of rat liver carcinogenesis initiated by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine and promoted by orotic acid. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:427–430. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ponzetto C, Bardelli A, Zhen Z, et al. A multifunctional docking site mediates signaling and transformation by the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor family. Cell. 1994;77:261–277. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paumelle R, Tulasne D, Kherrouche Z, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor activates the ETS1 transcription factor by a RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway. Oncogene. 2002;21:2309–2319. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vázquez-Chantada M, Ariz U, Varela-Rey M, et al. Evidence for LKB1/AMP activated protein kinase/endothelial nitric oxide synthase cascade regulated by hepatocyte growth factor, S-adenosylmethionine, and nitric oxide in hepatocyte proliferation. Hepatol. 2009;49:608–617. doi: 10.1002/hep.22660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardie DG, Hawley SA, Scott JW. AMP-activated protein kinase-development of the energy sensory concept. J Physiol. 2006;574:7–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Fan J, Yang X, et al. AMP activated kinase regulates cytoplasmic HuR. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3425–3436. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3425-3436.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez-Chantar ML, Vazquez-Chantada M, Garnacho M, et al. S-adenosylmethionine regulates cytoplasmic HuR via AMP-activated kinase. Gastroenterol. 2006;131:223–232. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolognani F, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. RNA-protein interactions and control of mRNA stability in neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:481–489. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garneau NL, Wilusz J, Wilusz CJ. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:113–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilusz CJ, Wormington M, Peltz SW. The cap-to-tail guide to mRNA turnover. Nat Rev. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:237–246. doi: 10.1038/35067025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma WJ, Cheng S, Campbell C, et al. Cloning and characterization of HuR, a ubiquitously expressed Elav-like protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8144–8151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park S, Myszka DG, Yu M, et al. HuD RNA recognition motifs play distinct roles in the formation of a stable complex with AU-rich RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4765–4772. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4765-4772.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu N, Chen CY, Shyu AB. Modulation of the fate of cytoplasmic mRNA by AU-rich elements: key sequence features controlling mRNA deadenylation and decay. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4611–4621. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bevilacqua A, Ceriani MC, Capaccioli S, et al. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression by degradation of messenger RNAs. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:356–372. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keene JD. Why is Hu where? Shuttling of early-response-gene messenger RNA subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang W, Furneaux H, Cheng H, et al. HuR regulates p21 mRNA stabilization by UV light. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:760–769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.760-769.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang W, Caldwell MC, Lin S, et al. HuR regulates cyclin A and cyclin B1 mRNA stability during cell proliferation. EMBO J. 2000;19:2340–2350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fan XC, Steitz JA. HNS, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling sequence in HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15293–15298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Güttinger S, Mühlhäusser P, Koller-Eichhorn R, et al. Transportin2 functions as importin and mediates nuclear import of HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2918–2923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400342101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rebane A, Aab A, Steitz JA. Transportins 1 and 2 are redundant nuclear import factors for hnRNP A1 and HuR. RNA. 2004;10:590–599. doi: 10.1261/rna.5224304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdelmohsen K, Lal A, Kim HH, et al. Posttranscriptional orchestration of an anti-apoptotic program by HuR. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1288–1292. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.11.4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katsanou V, Papadaki O, Milatos S, et al. HuR as a negative posttranscriptional modulator in inflammation. Mol Cell. 2005;19:777–789. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levadoux-Martin M, Gouble A, Jégou B, et al. Impaired gametogenesis in mice that overexpress the RNA-binding protein HuR. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:394–399. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van der Giessen K, Gallouzi IE. Involvement of transportin 2-mediated HuR import in muscle cell differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2619–2629. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Figueroa A, Cuadrado A, Fan J, et al. Role of HuR in skeletal myogenesis through coordinate regulation of muscle differentiation genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4991–5004. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.14.4991-5004.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gantt K, Cherry J, Tenney R, et al. An early event in adipogenesis, the nuclear selection of the CCAAT enhancer-binding protein {beta} (C/EBP{beta}) mRNA by HuR and its translocation to the cytosol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24768–2474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doller A, Pfeilschifter J, Eberhardt W. Signalling pathways regulating nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of the mRNA-binding protein HuR. Cell Signal. 2008;20:2165–2173. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abdelmohsen K, Pullmann R, Jr, Lal A, et al. Phosphorylation of HuR by Chk2 regulates SIRT1 expression. Mol Cell. 2007;25:543–557. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Lal A, et al. Nuclear HuR accumulation through phosphorylation by Cdk1. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1804–1815. doi: 10.1101/gad.1645808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li H, Park S, Kilburn B, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced methylation of HuR, an mRNA-stabilizing protein, by CARM1, Coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44623–44630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vázquez-Chantada M, Fernández-Ramos D, et al. HuR/Methyl-HuR and AU-Rich RNA Binding Factor 1 Regulate the Methionine Adenosyltransferase Expressed During Liver Proliferation, Differentiation, and Carcinogenesis. Gastroenterol. 2010;138:1943–1953. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cai J, Sun WM, Hwang JJ, et al. Changes in S-adenosylmethionine synthetase in human liver cancer: molecular characterization and significance. Hepatol. 1996;24:1090–1097. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.García-Trevijano ER, Latasa MU, Carretero MV, et al. S-adenosylmethionine regulates MAT1A and MAT2A gene expression in cultured rat hepatocytes: a new role for S-adenosylmethionine in the maintenance of the differentiated status of the liver. FASEB J. 2000;14:2511–2518. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0121com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pascale RM, Marras V, Simile MM, et al. Chemoprevention of rat liver carcinogenesis by S-adenosyl-L-methionine: a long term study. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4979–4986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Si-Tayeb K, Lemaigre FP, Duncan SA. Organogenesis and development of the liver. Dev Cell. 2010;18:175–189. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lemaigre FP. Mechanisms of liver development: concepts for understanding liver disorders and design of novel therapies. Gastroenterol. 2009;137:62–79. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamamoto H, Quinn G, Asari A, et al. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes: biological functions and therapeutic application. Hepatol. 2003;37:983–993. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cai J, Zhao Y, Liu Y, et al. Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into functional hepatic cells. Hepatol. 2007;45:1229–1239. doi: 10.1002/hep.21582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Banas A, Teratani T, Yamamoto Y, et al. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a source of human hepatocytes. Hepatol. 2007;46:219–228. doi: 10.1002/hep.21704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kang XQ, Zang WJ, Song TS, et al. Rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells differentiate into hepatocytes in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3479–3484. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i22.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Snykers S, Vanhaecke T, De Becker A, et al. Chromatin remodeling agent trichostatin A: a key-factor in the hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells derived of adult bone marrow. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tanimizu N, Saito H, Mostov K, et al. Long-term culture of hepatic progenitors derived from mouse Dlk + hepatoblasts. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 26):6425–6434. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fujikawa T, Hirose T, Fujii H, et al. Purification of adult hepatic progenitor cells using green fluorescent protein (GFP)- transgenic mice and fluorescence-activated cell sorting. J Hepatol. 2003;39:162–170. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nowak G, Ericzon BG, Nava S, et al. Identification of expandable human hepatic progenitors which differentiate into mature hepatic cells in vivo. Gut. 2005;54:972–979. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.064477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, et al. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatol. 2010;51:297–305. doi: 10.1002/hep.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gai H, Leung EL, Costantino PD, et al. Generation and characterization of functional cardiomyocytes using induced pluripotent stem cells derived from human fibroblasts. Cell Biol Int. 2009;33:1184–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lysy PA, Campard D, Smets F, et al. Stem cells for liver tissue repair: current knowledge and perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:864–875. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cho CH, Parashurama N, Park EY, et al. Homogeneous differentiation of hepatocyte-like cells from embryonic stem cells: applications for the treatment of liver failure. FASEB J. 2008;22:898–909. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7764com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martínez-Chantar ML, Latasa MU, Varela-Rey M, et al. L-methionine availability regulates expression of the methionine adenosyltransferase 2A gene in human hepatocarcinoma cells: role of S-adenosylmethionine. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19885–19890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang H, Sadda MR, Li M, et al. S-adenosylmethionine and its metabolite induce apoptosis in HepG2 cells: Role of protein phosphatase 1 and Bcl-x(S) Hepatol. 2004;40:221–231. doi: 10.1002/hep.20274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhuge J. A decrease in S-adenosyl-L-methionine potentiates arachidonic acid cytotoxicity in primary rat hepatocytes enriched in CYP2E1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;314:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heermann KH, Gültekin H, Gerlich WH. Protein blotting: techniques and application in virus hepatitis research. Ric Clin Lab. 1988;18:193–221. doi: 10.1007/BF02918884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gassmann M, Grenacher B, Rohde B, et al. Quantifying Western blots: pitfalls of densitometry. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:1845–1855. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marx J. Interfering with gene expression. Science. 2000;288:1370–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, et al. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fehrenbach H, Weiskirchen R, Kasper M, et al. Up-regulated expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products in cultured rat hepatic stellate cells during transdifferentiation to myofibroblasts. Hepatol. 2001;34:943–952. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, et al. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Duran J, Obach M, Navarro-Sabate A, et al. Pfkfb3 is transcriptionally upregulated in diabetic mouse liver through proliferative signals. FEBS J. 2009;276:4555–4568. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tenenbaum SA, Carson CC, Lager PJ, et al. Identifying mRNA subsets in messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes by using cDNA arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14085–14090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]