Abstract

An isolated fracture of the pisiform bone is a rare condition, especially in children. The fracture may be missed in the emergency department because of the complex anatomy of the carpal region. Early diagnosis and treatment are, however, important for the functional outcome of the patient, since untreated dislocated carpal fractures may result in nonunion. We report one case of a 9-year-old boy with an unrecognized fracture of the pisiform bone who underwent a pisiformectomy 10 months after injury due to a nonunion of the pisiform bone. Good results were obtained and the wrist did not show any functional impairment.

Introduction

A fracture of the pisiform bone is rare compared with other carpal bones. The estimated incidence of pisiform fractures is 1 to 3 % of all carpal bone osseous injuries [8, 16].

Fifty percent of pisiform fractures occur in combination with other carpal fractures or distal radius fractures and the other half are isolated fractures [7]. To the authors’ knowledge, only one report of two children with pisiform fractures has been published [13]. Dislocation of the pisiform bone has been described twice in children [1, 4]. Case reports concerning nonunion of pisiform fractures in adults and children have not been published so far. We report one case of a 9-year-old boy with a missed fracture and dislocation of the pisiform bone resulting in nonunion.

Case

A Dutch 9-year-old boy with a dominant right hand fell down while running, with an outstretched left arm and wrist in hyperextension, while on holiday. Immediately afterwards, there was diffuse swelling and pain on the ulnar border of the left wrist. Mobility was decreased significantly because of pain. He was seen at a local hospital on the same day. At physical examination, tenderness and swelling were present on the ulnar border of the hand and wrist. The initial standard AP and oblique radiographic views of the hand did not show any posttraumatic abnormalities and he was sent home without treatment (Fig. 1). After the holiday, he went back to school and continued playing football as a goalkeeper. He kept intermittent pain symptoms during cycling and goalkeeping. Also, resting on the wrist while standing and writing or typing was painful. After 10 months of persistent swelling of his left wrist, he was referred to our hospital by his GP. Physical examination revealed swelling over the proximal hypothenar eminence. Localized tenderness overlying the pisiform was noted. The range of motion was examined according to the AO Neutral-0 method. He had a full range of motion (flexion-0-extension 60-0-60) in his wrist. Grip strength, determined with a JAMAR dynamometer, was 92 % compared to his unaffected right hand. No ulnar paraesthesias were found. X-rays performed in our hospital showed an old volar, dislocated fracture of the pisiform with irregularity between the two fragments and signs of nonunion (Fig. 2). Therefore, no radiographs from the opposite wrist were made. The triquetrum was seen to be in its normal position without abnormal mobility. An operation was performed by excision of the superficial, nonunited pole of the pisiform bone (Fig. 3). The surgery’s results confirmed the suspected nonunion. Ulnar nerve decompression was not performed because there were no symptoms of ulnar nerve dysfunction. A wrist compression bandage was applied. X-rays did not show any abnormalities 3 weeks after surgical excision. No ulnar paraesthesias were found. The patient was re-evaluated 1 year after surgery. There were no complaints of pain, and he had a full range of motion of both wrists (flexion-0-extension 60-0-60). Grip strength, determined with a JAMAR dynamometer, was 100 % compared to his unaffected right hand. The patient was discharged from any further follow-up.

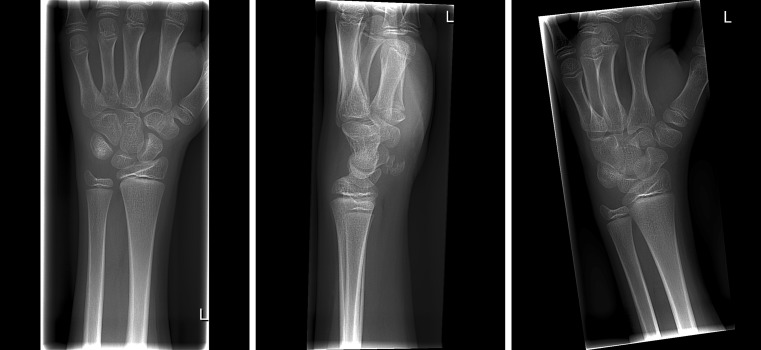

Fig. 1.

Initial standard AP and oblique radiographic views of the hand

Fig. 2.

Dislocated fracture of the pisiform with irregularity between the two fragments and signs of nonunion

Fig. 3.

Surgery performed by excision of the superficial, nonunited pole of the pisiform bone

Discussion

Case reports concerning nonunion of pisiform fractures in adults and children have not been published so far. To the authors’ knowledge, only one report of two children with pisiform fractures has been published [13]. Mancini et al. described two boys in the age of 12 and 13 who were treated with closed reduction of both the distal radius and two-fragment fracture dislocation of the pisiform under general anaesthesia and a short arm cast for 1 month. Good results were obtained. Re-evaluation after 30 years did not show any functional limitations [13].

Pisiform dislocation is also very rare in children and has only been described twice last century. In 1922, Cohen described an 11-year old boy with a Salter-Harris type I fracture of the distal radius and anterior dislocation of the pisiform. The epiphysis was partially reduced without anaesthesia. An attempt was made to reduce the dislocation of the pisiform by strapping a gauze pad with elastoplast over this bone. The function of the hand returned within 15 days. Unfortunately, the patient did not show up at further follow-up [4]. Ashkan et al. described in 1998 a dislocated pisiform associated with type II Salter-Harris fractures of the distal radius and ulna in a 9-year-old child. Closed reduction followed by immobilization achieved good radiological and clinical results [1].

The pisiform, whose centre of ossification appears between 7.5 and 10 years, is the last carpal bone to ossify. The bone is fully developed by the age of 12. Before this age, there may be multiple centres of ossification, giving it a fragmented appearance [7]. This appearance should be distinguished from a fracture, and if uncertain, it may be helpful to perform radiographs of the opposite wrist or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan [10]. In our case, the borders appeared more irregular than in a pisiform fragmented in multiple ossification centres and the patient had complaints supporting a traumatic event.

Fractures and dislocations of the pisiform are often due to an isolated, direct trauma on the hypothenar eminence. Hyperextension of the wrist in combination with eccentric contraction of the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) can result in an osteochondral or avulsion fractures or dislocation of the pisiform [5]. Especially protectors of the hand worn during inline skating are known to transmit substantial forces to the pisiform bone when falling and result in a fracture of the pisiform [5].

Secondary to a distal radius fracture, the pisotriquetral joint can dislocate simultaneously as result of relaxation of the capsular tissue [1]. In our case, hyperextension of the wrist with maximal eccentric contraction of the flexor carpi ulnaris probably caused the pisiform fracture.

There is a typical clinical presentation. At physical examination, pain, tenderness and swelling are present on the proximal hypothenar eminence [17], as was also the case in our patient. If there is a non-dislocated fracture of the pisiform, no wrist deformity and a full range of wrist motion can be found [17]. Unlike a non-dislocated fracture of the pisiform, in a dislocated pisiform or fracture dislocation, a depression is present on the ulnar part of the wrist and a decrease in range of motion of the wrist may appear. The ulnar nerve in Guyon’s canal can be damaged in case of a pisiform fracture and accompanying symptoms and signs may occur [7]. There are various reasons for hypothenar pain such as hamate fracture, tendinitis of the FCU, pisotriquetral chondromalacia and arthritis. Carpal ligamentous disruptions must be distinguished from a fracture of the pisiform [19].

Four radiographic images of the wrist are required for optimal visualization of fractures of the wrist or carpus: posterior-anterior, lateral, semi-pronated oblique and scaphoid view (PA view with ulnar deviation and 30° supination) [18]. The pisiform fracture may be missed on routine radiographs in the emergency room, as was the case with our patient. Unfortunately, the local hospital did not perform a lateral view of the wrist. Other special radiographic techniques to view the pisiform or pisotriquetral joint such as “20° supinated lateral wrist view”, “carpal tunnel view” and “reverse oblique view” may be helpful [11, 15].

Dislocation of the pisiform bone can be diagnosed on the lateral view of the wrist. In case of suspected subluxation of the pisotriquetral joint, the diagnosis is made when one or more of the following are present: proximal or distal overriding of the pisiform amounting to more than 15 % of the width of the joint surfaces and/or loss of parallelism of the joint surfaces greater than 20° or joint space of the pisotriquetral joint wider than 4 mm [17].

In adult patients with a clinically suspected fracture but no abnormalities on radiographic imaging, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the wrist should be obtained for further evaluation. A CT scan has shown that it is well suited to demonstrate a pisiform fracture in either the coronal or transaxial plane because of the cross-sectional images and a high resolution [9].

In contrast to CT, however, MRI is able to detect fragments of bone as well as cartilage fragments, especially in children [6]. Cartilage is radiolucent on plain film. We did not perform an MRI, although it would have been helpful in evaluating articular fractures to identify fracture pattern and extent, fragment position and any interposed structure. The surgery’s results confirmed the suspected nonunion.

Beckers and Koebke showed that the pisiform is important in providing mechanical stability to the ulnar column of the wrist by holding the triquetral bone in a correct position and preventing it from subluxation. Moreover, the researchers concluded that the pisiform is an important fulcrum for transmitting powerful forces because of its position between the hand and the forearm and suggested that surgical excision of the pisiform might cause possible malfunction of the wrist [2].

Lam et al. investigated the clinical and functional outcome of the wrist after pisiformectomy for pisotriquetral joint dysfunction and concluded that there were no significant differences in grip strength and range of wrist motion [12]. They reported no postoperative FCU dysfunction and subluxation of the FCU tendon.

Carroll and Coyle conducted research on adults with chronic pain at the pisiform area due to malunion or nonunion (three patients), subluxation and dislocation or pisotriquetral arthritis. Complete relief was obtained in 65 of 67 patients after resection of the pisiform bone and patients rarely experienced any long-term disabilities [3].

Similar results were obtained by Palmieri. Twenty-one of 33 patients (five patients with painful union or nonunion) who underwent pisiformectomy due to failure of casting showed good results [14]. Vasilas et al. noted that none of their 13 patients with pisiform fractures, including one fibrous nonunion, required excision [17]. Lacey and Hodge suggested immobilization in a cast for a period of 4 to 6 weeks and excision for those patients who fail immobilization or present with nonunion or ulnar neuropathy [11]. All these articles showed that casting and early and delayed excision have been reported as first choice treatments. Due to the rarity of the pisiform fracture, there is no clear consensus regarding treatment.

Conclusion

A pisiform fracture is rare in children, and as far as we know, nonunions have never been described. Visualization of the fracture is difficult when using standard radiographs. The pisiform can be seen with a reverse oblique view, 20° supinated lateral wrist view and carpal tunnel view. The fracture may be missed before the age of 12. Before this age, there may be multiple centres of ossification, giving it a fragmented appearance. MRI can be helpful in the evaluation of cartilage fragments and to differentiate between a fracture or double centres of ossification in case of doubt. Malunion, nonunion, limitations in the range of wrist motion and ulnar nerve injury are reasons for surgical excision of the pisiform. We presented one case in which a nonunion of the pisiform bone was diagnosed only on the lateral radiograph. The treatment with excision of the nonunited pole of the pisiform bone and wrist compression bandage achieved good results, with no functional impairment.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Lars Brouwers declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Pascal F.W. Hannemann declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Peter. R.G. Brink declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Contributor Information

Lars Brouwers, Phone: +31-76-5954250, FAX: +31-76-5953818, Email: Lars_brouwers@hotmail.com.

Pascal F. W. Hannemann, Email: p.hannemann@mumc.nl

Peter. R. G. Brink, Email: p.brink@mumc.nl

References

- 1.Ashkan K, O’Connor D, Lambert S. Dislocation of the pisiform in a 9-year-old child. J Hand Surg (Br) 1998;23(2):269–70. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(98)80195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckers A, Koebke J. Mechanical strain at the pisotriquetral joint. Clin Anat. 1998;11(5):320–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1998)11:5<320::AID-CA5>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll RE, Coyle MP., Jr Dysfunction of the pisotriquetral joint: treatment by excision of the pisiform. J Hand Surg. 1985;10(5):703–7. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(85)80212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen I. Dislocation of the Pisiform. Ann Surg. 1922;75(2):238–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192202000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dufek P, Thormahlen F, Ostendorf U. Fracture of the pisiform bone in inline skating. Sportverletzung Sportschaden : Organ der Gesellschaft fur Orthopadisch-Traumatologische Sportmedizin. 1999;13(2):59–61. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ecklund K. Magnetic resonance imaging of pediatric musculoskeletal trauma. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;13(4):203–17. doi: 10.1097/00002142-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleege MA, Jebson PJ, Renfrew DL, Steyers CM, Jr, el-Khoury GY. Pisiform fractures. Skelet Radiol. 1991;20(3):169–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00241660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geissler WB. Carpal fractures in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20(1):167–88. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hindman BW, Kulik WJ, Lee G, Avolio RE. Occult fractures of the carpals and metacarpals: demonstration by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153(3):529–32. doi: 10.2214/ajr.153.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohler A, Zimmer EA. Borderland of the normal and early pathologic in skeletal roentgenology, third American edn. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacey JD, Hodge JC. Pisiform and hamulus fractures: easily missed wrist fractures diagnosed on a reverse oblique radiograph. J Emerg Med. 1998;16(3):445–52. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(98)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam KS, Woodbridge S, Burke FD. Wrist function after excision of the pisiform. J Hand Surg (Br) 2003;28(1):69–72. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancini F, De Maio F, Ippolito E. Pisiform bone fracture-dislocation and distal radius physeal fracture in two children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14(4):303–6. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200507000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmieri TJ. Pisiform area pain treatment by pisiform excision. J Hand Surg. 1982;7(5):477–80. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(82)80043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papilion JD, DuPuy TE, Aulicino PL, Bergfield TG, Gwathmey FW. Radiographic evaluation of the hook of the hamate: a new technique. J Hand Surg. 1988;13(3):437–9. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(88)80026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seitz WH, Papandrea RF. Fractures and dislocations of the wrist. In: Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, editors. Rockwood and Green’s fractures in adults. 5. Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasilas A, Gireco RV, Bartone NF. Roentgen aspects of injuries to the pisiform bone and pisotriquetral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol. 1960;42A:1317–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeitoun F, Frot B, Sterin P, Tubiana JM. Views necessary for the traumatic wrist. Ann Radiol. 1995;38(5):255–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman NB, Mass DP. A pisiform fracture. Orthopedics. 1987;10(5):817–20. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19870501-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]