Abstract

Most dementia research investigates the social context of declining ability through studies of decision-making around medical treatment and end-of-life care. This study seeks to fill an important gap in research about how family members manage the risks of functional decline at home. Drawing on three waves of retrospective interviewing in 2012–2014, it investigates how family members in US households manage decline in an affected individual’s natural range of daily activities over time. The findings show that early on in the study period affected individuals were perceived to have awareness of their decline and routinely drew on family members for support. Support transformed when family members detected that the individual’s deficit awareness had diminished, creating a corresponding increase in risk of self-harm around everyday activities. With a loss of confidence in the individual’s ability to regulate his or her own activities to avoid these risks, family members employed unilateral practices to manage the individual’s autonomy around his or her activity involvements. These practices typically involved various deceits and ruses to discourage elders from engaging in activities perceived as potentially dangerous. The study concludes by discussing the implications that the social context of interpretive work around awareness and risk plays an important role in how families perceive an elder’s functional ability and manage his or her activity involvements.

Keywords: US; Alzheimer’s/dementia; symptom management, autonomy; functional decline; awareness; risk

In the US, seventy percent of the 5.4 million people who have Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are cared for at home (Alzheimer’s Association, 2012). With the number of individuals who have dementia expected to grow significantly over the coming decades (Brookmeyer, Gray, & Kawas, 1998), household care likely will grow in proportion. Prior research has made progress in explaining important household consequences of the disease, including shifts in identities and interpersonal relationships (see Bunn et al., 2012). Yet there are still important gaps in understanding how dementia is reshaping the social order of millions of households. While research has highlighted the importance of autonomy and meaningful activity to the wellbeing of cognitively-declining elders (Everard, Lach, Fisher, & Baum, 2000; Moyle et al., 2011; Phinney, Chaudhury, & O'Connor, 2007; Popham & Orrell, 2012; Wenborn et al., 2013), it has not yet explained how family members manage functional decline in the elder’s daily activities over time. This is an important gap in dementia research because 1) functional decline is associated with increased stress and burden for caregivers (Vitaliano, Zhang & Scanlan, 2003) and 2) responses to dementia by family members can influence long-term prognosis (Tschanz et al., 2013).

Research developing around the concepts of ‘functional decline’ and the ‘activities of daily life’ has not pursued a line of inquiry examining how householders interpret and influence the process over time. Rather, research around these concepts has sought different goals, including developing measures of decline and activity level and identifying psychological and neurological correlates of these measures. The current study frames functional decline as a social problem that householders interpret and attempt to manage in their everyday lives across the progression of the disease (see Beard & Fox, 2008 for a parallel social problems framing). It asks: how does a family deal with a member’s gradual decline in activities that he or she had been competently performing for decades? How do they manage everyday household threats—including house fires, floodings, poisonings, car accidents, and financial escapades—that incompetence in daily activities may cause? Important theorizing in dementia research suggests the crucial role of social psychological factors in determining the level and expression of functional ability (Clare, 2002; Kitwood, 1997; Sabat, 2001). The current study expands on these ideas by showing how the social context of household care mediates individual expressions of functional decline.

Studies of social support around decision-making provide a useful foundation for a social process understanding of functional decline. This research examines how family members manage the affected individual’s decisions around medical treatment, end-of-life care, finances, and moves to long-term care facilities (Davies & Nolan, 2003; Chrisp, Tabberer, & Thomas, 2013; Menne, Tucke, Whitlatch, & Feinberg, 2008; Samsi & Manthorpe, 2013; Wackerbarth, 2002). An important dimension of the work characterizes the level of involvement elders and caregivers have in the decision-making process and the effects that different levels of involvement have on caregivers and elders individually and on their relationship. Findings highlight the challenges families face in executing decisions that correspond with the authentic preferences of affected individuals, but do not explicate how management of the decision-making process relates to avoiding risks caused by waning functional ability more generally. Thus, this area of work examines social support around cognitive decline through a narrow strip of behavior that provides limited insight into the larger process occurring across the individual’s natural range of activities.

A second, smaller collection of studies offer modest insights into the larger process, especially around familial attempts to help the individual maintain ability-based dimensions of personal and social identities. Linking identity to activity participation, a number of studies, for instance, tie the effort of promoting autonomy to the concern with preserving or protecting the individual’s identity (Berry, 2014; Blum, 1991; Clare, 2002; Fontana & Smith, 1989; Perry & O’Connor, 2002; Phinney, 2006; Phinney, Chaudhury, & O'Connor, 2007). Perry and O’Connor (2002), for instance, describe how caregivers decrease the complexity of the elder’s old activities so that they may still engage in them to some extent and preserve a sense of self identity. In complementary work, Clare (2002) identifies the coping strategies that family members and affected individuals collaboratively constructed in order to maintain normality and protect a sense of self. Relevant to the current study, she highlights how family members “struggled” to find the balance between constructively helping and “taking over in an undermining way” (143). Finally, the current piece also builds on work explaining how family members engage in “cognitive support work” in order to minimize confusion and disorientation in the elder’s social interactions (Berry, 2014). This piece identifies the lay health practices that family members develop to minimize the effects of symptoms on everyday life. Whereas that work focuses on attempts to lessen confusion so that the individual can effectively maintain independent lines of conduct, the current piece focuses on attempts to manage involvement in everyday activities to lessen risk of injury to self and others.

While the literature offer insights into social support around ability decline, researchers still know little about how family members manage decline in an elder’s natural range of daily activities—such as cooking, driving, shopping, and bathing—over time. Though researchers have developed numerous interventions designed to increase functional autonomy at home (see McLaren, LaMantia, & Callahan, 2013), there is little research elucidating how families navigate functional decline within the social context of their own households. This work advances the study of functional decline in dementia by revealing how family members become autonomy management practitioners who develop their own logics of support.

Methodology

Sample

This is a three-wave retrospective interview study with individuals who provide caregiving to relatives diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. In total, we conducted 45 interviews with 15 individuals over the course of 2 years (2012–2014). We recruited this non-probability sample through the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the University of California, Davis following IRB approval. Among these participants, 12 were adult-children and 3 were spouses of the affected individual. We utilized a pool of Latina caregivers assembled for a related project investigating the effects of social capital on dementia caregiving. When the study began, participants ranged in age from 44 to 77 and care recipients ranged in age from 67 to 96. Time since diagnosis ranged from 1 to 12 years with a mean of 3.73 years. Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease about whom participants reported displayed varying degrees of disease advancement at the start of the study. Twelve of the fifteen participants lived with the individual with dementia part time (5 of 15) or full time (7 of 15). In these part time living arrangements, participants either stayed part of the week at the affected individual’s home or switched off with a sibling in hosting the individual weekly.

Data Collection

The findings were derived from data collected through three waves of in-depth, open-ended interviewing conducted over the course of 2 years. We interviewed participants three times each at six month intervals. In the first interview, we focused our questions on the period from the first signs of the disease until the moment of the interview. In the subsequent two interviews, we focused on the period since the last interview. Interviews typically lasted between an hour-and-a-half and two hours each. They were conducted by phone or in person and in Spanish or English depending on the participant’s preferences. In total, 29 were conducted by phone and 16 were conducted in person. All interviews were digitally recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Each participant received a $40 gift card for participating in each interview.

We began the interview process with the understanding that current research does not explain satisfactorily how families deal with the household risks that occur due to cognitive decline. We conducted interviews using an interview guide that we constructed before each wave of interviewing. We designed each interview guide to accomplish two main tasks: (1) to understand the nature of the participant’s relationship to the affected individual over time and (2) to document the participant’s concrete behaviors around the elder’s daily activities over time. We accomplished the first task by asking questions about living arrangements, amount of time spent together, and the types of activities that they engaged in together. To complete the second task, we asked questions about the participant’s perception of the affected individual’s abilities in his or her common daily activities over time and about the participant’s behaviors around the elder during these activity involvements. We asked participants to describe the step-by-step details of how specific events and situations had occurred in their households and discouraged participants from speaking in generalizations and abstractions (Becker, 1998).

Because trust is a crucial interpersonal achievement when seeking to gain insight into a stigmatized health condition like Alzheimer’s, we made rapport-building a cornerstone of our research design. First, we used a multi-wave interview protocol to increase the likelihood of building trust and facilitating participant disclosure of emotionally-difficult occurrences (Weiss, 1994). Second, we selected an interviewer that shared a racial-ethnic background and language fluency with our participant sample and relied on her (Yarin Gomez, the third author) to conduct each interview.

Analytic Procedures

The analysis consisted of a modified grounded theory procedure that entailed engaging directly with the research literature related to functional decline during the coding process (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). Each author engaged in line-by-line coding of the complete set of interview transcripts unassisted by qualitative coding software. This approach helped us identify a common substantive interest and establish inter-coder reliability. The topic of autonomy management around functional decline emerged out of the first round of coding. Through this phase of analysis we learned that family members exhibited substantial concern with the risks of household injury and with how much influence they should exert over their mom, dad, or spouse in everyday activities.

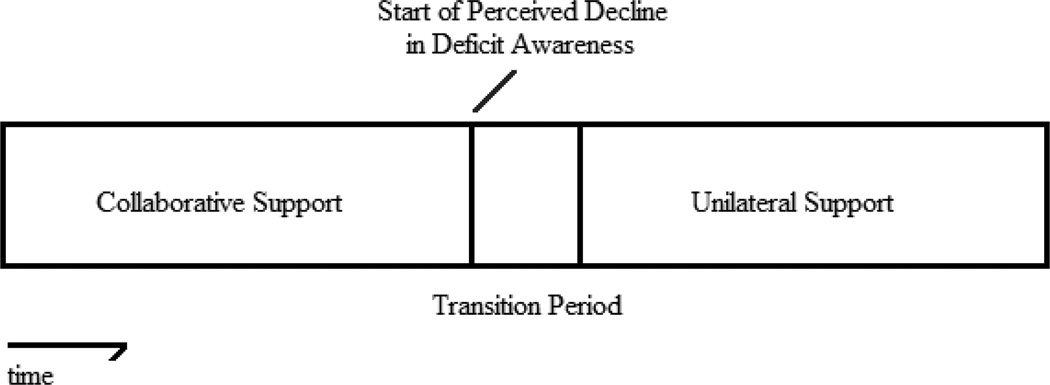

In a subsequent phase of coding, we identified the techniques and management practices that family members used to influence the elder’s activity involvements and placed them in typological categories. In a final phase of analysis, we examined these practices for discernible trends and turning points from the onset of the disease until the final interview. To facilitate this process, we developed summary timelines that visually depicted each participant’s shifts in management behavior over time. We compared these timelines and identified the common stages between them. This analytic technique revealed that participants began shifting from collaborative to unilateral autonomy management techniques when they detected the elder’s waning deficit awareness. The research team met regularly to discuss this ongoing analytic work and to resolve interpretive discrepancies through a consensus building process. Interpretive discrepancies typically occurred when determining if a family member’s response to an elder’s behavior fit within a category we had previously identified.

Findings

The findings show that family members managed the elder’s involvement in daily activities across three stages of support: a collaborative, transition, and unilateral stage. The collaborative stage began early on in the disease trajectory when elders drew on family members for support in pursuing their decades-old activities. Support entered a transition period when family members began to perceive that the elder was exhibiting diminishing deficit awareness with a corresponding increase in risk of self-harm around everyday activities. With a loss of confidence in the elder’s ability to regulate his or her activities to avoid these risks, family members employed unilateral practices to manage the elder’s autonomy around his or her activity involvements. In sum, all participants had at least entered the transition period and five had entered strictly into the unilateral stage of support.

Collaborative Support Stage

(1) Activity Preferences Remained as Cognitive Ability Declined

Family members reported that as elders lost cognitive ability, interest in decades-old activities and routines did not wane substantially. A majority of elders from this study’s sample continued to display pre-symptomatic activity preferences, sometimes for many years after diagnosis. One man, for instance, continued to drive his truck around an adjacent orchard and frequently expressed a desire to drive it in the nearby town as he had done for many decades even though he had gotten lost a number of times in recent months and had a minor accident. A woman continued to prepare food in her kitchen even though her creations were seen as sometimes un-edible by her family members. Another woman took regular walks to the grocery store though she frequently showed signs of confusion in everyday tasks and her daughter had taken to monitoring her walks from the front yard. These cases conform to a larger pattern of family member reports indicating that as mental acuity declined for elders, desire to engage in familiar activities largely remained.

(2) Exhibiting Awareness of Decline and Adjusting Activity Involvements

Early on in the disease trajectory, family members reported that elders exhibited awareness of their own ability decline through direct acknowledgment of their deficits or indirectly through their efforts to work collaboratively to avoid the problems they could cause. One family member noted that her mother showed awareness of her cognitive decline by drawing on a light bulb as a metaphor for describing her intermittent cognitive failings. She reported,

She goes “se me apaga el foco [my lightbulb turns off].” So now it’s a joke between her and me, and I say “How’s your foco [lightbulb]?” She goes, “Oh, it’s fine.” I said, “Okay, I am going to take you to the doctor.” She says, “Why?” “Well you need to see if you need another foco [lightbulb].” “Oh,” she goes, “okay,” and then she’s fine with it.

Another noted that though her mother was losing cognitive ability, she had maintained awareness of her limitations. She reported that her mom occasionally acknowledged her decline by vocally reflecting on what activities she was still able to manage independently: “[My mom will] say, ‘I can wash dishes. That’s still one thing I can do.’ So she knows she’s sick.”

Family members observed indirect evidence of the elder’s deficit awareness through the collaborative efforts they took with them around their deficits. Collaborative work primarily took two forms: 1) elders requested from family members assistance around their activity involvements or 2) they followed the suggestions of family members for avoiding problems that their deficits might cause. Elders made several types of requests for assistance around their activity involvements. In some requests, elders asked for long-term support, acknowledging the permanency and progression of their ability decline. For instance, a mother requested that her daughter move in to her home and provide greater support. Emphasizing her mother’s forcefulness in requesting the support, the daughter recounted the conversation, “She goes, ‘You’re not going anywhere. You are staying here, and that’s final.’ … So since 2010 I have been living there with my parents and caring for [my] mom …’ In other requests, elders sought momentary assistance to perform certain tasks. One woman pointed out her husband’s occasional requests for help in navigating the home they had lived in for many years. He sometimes asked: “Is that the bathroom?” And [I would say], “Yeah, that’s the bathroom.”

Elders also showed awareness of their deficits by willingly engaging in collaborative work with family members to boost their functioning in certain activities. In one dimension of this work, family members established agreements with elders about the kind of support they needed around their everyday activities. The daughter of a woman with Alzheimer’s, for instance, worked with her mom to determine the precise kind of support she wanted at home. She explained:

So I said, okay, so it’s okay for her to wash the clothes? “No, no, I can do it.” “Is it okay for her to hang the clothes?” “Yeah, she can hang the clothes…” “Is it okay for her to fold the clothes? … Can she put the clothes away?” … I broke all that down and … my mom was part and parcel of the decision making of her home…

In other cases, elders acknowledged their deficits by heeding the warnings of their family members about how to safely navigate their daily activities. The wife of a man with Alzheimer’s said that he largely followed her rule of no more driving in town because “he knows that he won’t be able to go to town and come back without getting lost.” Thus, for family members, the elder’s deficit awareness was integral for engaging in collaborative work to boost independent functioning.

Family members reported the importance of maintaining a collaborative approach to limiting the elder’s independence, suggesting that unilateral measures could injure their relationships. One noted, “I don’t want to make drastic changes in her life … especially if it is going to come to where she thinks I am making these choices for her. I am going to let her keep going. Like I said, I am trying to make her understand she needs to work with us.”

In sum, family members reported that engaging in effective collaborative support was dependent on the elder having awareness of how his or her declining ability could lead to trouble in daily activities. Elders showed deficit awareness through direct vocal acknowledgment and by engaging in collaborative support practices with family members. Family members sought to engage in collaborative support with elders as a safeguard against creating unnecessary tension in the relationship.

Transition Period

(1) Detecting Spotty Deficit Awareness and Attempting to Improve It

Over time family members began detecting the elder’s increasingly spotty awareness of his or her declining abilities. This initiated the process by which family members came to see elders as unfit collaborators around managing activity involvements. They detected an elder’s waning deficit awareness in multiple ways, such as by observing 1) distressing failure events in daily activities, 2) statements of overestimated abilities, and 3) immediate behavioral blindness. One daughter noted, for instance, that though her mother displayed confidence about navigating by car, it belied her actual ability. She treated this as a sign that her mother was not in touch with her remaining abilities. She noted, “She said she knew where she was going. She got lost. We had to go get her in the Home Depot parking lot off of Hatter Road. She did not know where she was going. Thank goodness my niece was with her.” In another case, a woman found that her mom occasionally overestimated her abilities: she noted, “[My mom] thinks that she has a capability to do things she can’t do. … [She’ll say,] ‘I’ll go ahead and take care of that.’ Or, ‘tomorrow, I’m going to go ahead and fix this.’ Stuff that she can’t take care of or fix.” Lastly, family members inferred an elder’s compromised deficit awareness by observing his or her inability to recall the immediate past. They reasoned that if individuals showed little to no awareness of what just occurred, they are likely unable to remember their own subtle changes in ability. A daughter, for instance, inferred her mother’s spotty deficit awareness through a kind of test in which she immediately mimicked her mother’s disturbing use of curse words. She reported, “I repeat it to her and she tells me, ‘what big words you are saying. You are going to go to hell.’ And then I see that it’s ‘cause she does not even know what she is saying.’” Later, met with the claim by her son and daughter that she had an illness, she responded to a third party, “[they] are crazy, not [me].”

Family members sometimes faced interpretive challenges around identifying moments of compromised deficit awareness. They reported that elders routinely avoided acknowledging their errors or oversights in their daily activities, leaving family members unsure if they were aware of the mistake they had made or were trying to avoid discussing the matter out of embarrassment. One family member faced this interpretive challenge after her father made a cup of coffee that contained the coffee grounds. She noted, “Yeah, so I’m like, ‘Why didn’t you use the coffee maker, you know?’ He’s like, ‘Oh.’ It’s like he realized that he didn’t do it well, but he was too embarrassed to admit it.” In another case, the daughter of a woman with dementia suggested her uncertainty about her mom’s awareness level after observing her failed use of the microwave and apparent attempt to deny the failure.

So I had noticed it was getting harder and harder for her to use [the microwave]. … [T]his one visit … I had bought them like soup for my dad, and told her, “Okay mom, this is all in here in the refrigerator.” I said, “You know, just put it in a bowl and warm it up.” … So when I got home from work, I asked my dad, “Well, what did you eat?” He said, “Cold soup.” I said, “Mom, you didn’t warm up the soup?” She said, “No, he likes it cold.”

The daughter expressed uncertainty about whether her mom was trying to cover up her inability to use the microwave and thus was aware of that deficit or was not actually aware that she used it incorrectly or skipped the step entirely.

Upon discovery of the elder’s spotty awareness, family members reported developing a heightened vigilance for trying to detect and respond to functional decline before it caused problems. Fear of the individual setting the house on fire, poisoning others with cleaning products such as the popular American brand Pine-Sol, flooding the house with water, or running someone over gripped many as a near crisis-level threat. As a result, they began concerning themselves with how much autonomy to give the individual in their normal activities. One commented on this challenge: “… [S]he wants to do more things, she just can’t remember how to do them all the time. … So we have to kind of be careful what we have her do … and we try to stimulate her by having her do something, but we have to be careful…”

In addition to increasing their vigilance, some family members tried to improve deficit awareness in elders so that they would notice errors in ability and possibly improve upon these oversights. Resembling the reality orientation work used by some caregivers, the daughter of a woman with Alzheimer’s instructed her son to always make his grandma acknowledge her errors. After his grandma forgot to warm up his tortillas, he said he felt bad bringing it to her attention despite his mother’s insistence that he do it. His mom told him, ‘“You have to bring that to her attention. She might not remember after you tell her. But don’t let an episode like that go. Say, ‘Nana, these aren’t warm. You’re giving me cold tortillas.’ … I go, ‘Make her acknowledge that this has happened because in her mind she’s not doing anything wrong.’”

In sum, collaborative autonomy management work began to break down when family members saw affected individuals as unable to work with them to minimize risks. This path sometimes proved circuitous. Some struggled to make sense of early signs of spotty awareness, while others attempted to improve upon them.

(2) Activity Trials and Social Deliberation

When family members perceived that the elder’s ability level in a certain activity was reaching a risky level, commonly that activity attracted greater scrutiny from them and other family members. The activity, in a sense, was put on trial. Family members began monitoring them more in that activity and began deliberating with other family members about whether they should somehow curtail their independence in that activity. They were motivated by the concern that with intermittent awareness, elders became unable to choose activities appropriately for their declining state of cognitive functioning.

Family members reported periods of indecision and uncertainty about how to respond to the elder’s involvement in activities that posed varying levels of immediate risk. Several participants recalled increasing scrutiny of their mom’s ability to cook and perform other activities in the kitchen after she left the stove on and filled the house “full of gas,” began regularly to burn things, or flooded the house with water. Another indicated that she was not certain about whether her mom should continue in the household role of checking the mail, especially after learning that she was regularly missing her doctor’s appointments and ignoring the notices that they had sent. She noted,

… [W]e’ve noticed that … things that are supposed to come to us … I haven’t gotten. … Whatever she puts on the table, that’s what we know came in the mail. So I don’t know what she hides or what she doesn’t. You know, if bills are being paid on time, or if she has lapsed on some of them. You know, I have no control over that, and I do worry about that…

During these moments of deliberation about whether to try restricting an elder’s independence in an activity, family members routinely employed the help of others. One daughter, for instance, reported regular discussions with her sister about how they should deal with their parents who had both shown signs of dementia and a failure to maintain their medication regimens. She noted, “I knew that they weren’t taking their medication. So I talked to my sister about it, and we started trying to see if we could get like a nurse to come in … and make sure that they were taking [them].”

Family members routinely encountered contrasting assessments of the elders’ abilities by others in the household when seeking to establish a common approach to managing their autonomy. The daughter of a man with Alzheimer’s was struck by how much her brother’s assessment of their father’s abilities contrasted with hers. She sought her mother’s opinion on the matter as a bellwether. “My brother sees him totally different than I see him. I see him frail. [He sees] him … and it’s like … ‘He’s doing good. He’s doing really, really good.’ So I’m just like ‘Really? You really think so?’ … [My mom] says, ‘… don’t listen to him. He’s not doing good.’ She conceded being unsure of whether her brother’s approach of encouraging their dad’s independence in contrast to her independence-restricting approach could improve his wellbeing. She continued, “… I don’t know if the psychology of the whole thing is better that he tells him, you know, ‘Hey dad, you’re fine. You know, you can do it yourself.’ … I don’t know.”

Family members at times observed among their family members what they deemed to be denial of the elder’s need for reduced independence. The daughter of a woman with Alzheimer’s described the initial challenge of getting the family on board with her plan to limit her mom’s independence. She noted, “My sons are in denial with their Nana, you know, not remembering… They’re always telling me, ‘Leave my Nana alone, leave my Nana alone…’” She recalled her son’s attempt to cover up her mom’s declining ability to navigate the local area while driving: “She had my son driving for an hour one time because they couldn’t find [their destination]. And [my son] goes, ‘Mom … it was my fault because I was talking to her.’ But she should have known where it was… It’s just down the street and you turn the corner at the light.”

When one family member settled on a strategy of limiting independence around a particular activity, they sometimes found it difficult to get others to accept the level of supervision the elder needed in order to avoid serious harm. These occasions were commonly the source of tension between family members. The daughter of a woman with Alzheimer’s, for instance, lost patience with her dad after he failed to provide what she deemed to be adequate supervision around her mom’s cooking. She described how she reacted toward her dad: “Dad, did you see what is happening? There’s a paper towel on a saucepan with paper plates on top of that and the flame is two inches from the paper towel. You have to watch her. … It’s like watching a two-year-old. … You don’t leave a two-year-old unattended.”

Unilateral Support Stage: Using Assistive and Restrictive Techniques to Manage Autonomy

As family members perceived increased declines in deficit awareness, they reported losing much of the elder’s effective collaboration in reducing the risks associated with their activity choices. They discovered, for instance, that elders showed less ability to form and stand by previous agreements about avoiding certain activities or avoiding them without proper assistance. As a result, family members began developing and relying on unilateral techniques, or techniques that did not require the elder’s personal investment in the goal of avoiding certain risky activities or the riskiness within them. The study highlights two forms of unilateral autonomy management work: assistive and restrictive. Family members drew on these techniques to varying degrees depending on the extent to which they observed risky behaviors (which varied according to the elder’s activity choices and state of fluctuating ability in these activities), expected resistance to their management efforts, or felt pre-occupied by their caregiving workload.

(1) Assistive Work

Family members engaged in assistive work in order to minimize incompetent acts in the elder’s activities and any associated risks that such acts could bring. The character of the assistive work varied across the study sample depending on multiple factors, including the family member’s depth of involvement and desire to be covert. At the lowest level of involvement, family members provided convenience assistance. In this form of assistive work, family members helped elders engage in activities if they happened to observe them facing a challenging moment. One participant provided an illustration:

…[S]he had just washed the dishes, and she was staring at the knife. She goes, “Now where does this go?” … And she wanted to go put it in the coffee cupboard where all of the coffee cups are. She said, “No, it doesn’t look like that.” I go, “Go put it in the drawer, mom.” She goes, “Oh that’s right, it goes in here.”

Family members increased their level of assistive work by utilizing nuanced understandings of what the elder was still capable of doing and the schedule by which they would likely seek to do them. One daughter, for instance, demonstrated a detailed understanding of what activities her mom could still engage in competently. She noted, “She can’t wash the clothes anymore… She can separate the clothes… She can iron the shirts… She washes dishes, but she doesn’t know where they go. … I pour her her coffee, put in her milk, because she can’t do that anymore. … [S]he doesn’t know what a refrigerator is.”

At this heightened level of assistive work, family members reported learning and internalizing the idiosyncratic schedule by which the elder sought to engage in certain tasks. They used this understanding to create an assistive net around the elder’s activity involvements to insure that they would be in the right place at the right time. At the greatest depth of assistance, family members learned the elder’s bathroom schedule and facilitated use at the appropriate times. One demonstrated her knowledge of her mother’s schedule: “I take her to bed at 10 PM and I take her before laying her down to the bathroom and I already know that at 3 AM I have to get her up again for the bathroom. If for any reason I am late 5, 10 minutes after 3 AM, she already went to the bathroom.”

When deemed necessary, family members performed some of this assistive work covertly in order to reduce the likelihood of causing the elder embarrassment and/or possibly eliciting resistance. Several family members described tactics of secretly cleaning the elder’s bedroom or bathroom when it seemed he or she was unaware of how unhygienic it had gotten. One daughter reported routinely cleaning up in the bathroom after her mom had finished using it. She noted, “I don’t say anything to her because it would embarrass her. I will just flush it.”

An important dimension of the assistive work involved directing the elder toward activities they believed would increase his or her wellbeing. Many family members reported that they could no longer count on elders to find and successfully engage in their old routines and activities despite their belief that it was important for elders to affirm their personal identities in familiar activities. One family member noted the importance of helping the elder remember when her favorite television show was airing by placing notes on the television. Another described reading to her mom when she began to show diminishing interest in her favorite novelas.

(2) Restrictive Work

Family members engaged in restrictive work in order to prohibit elders from engaging in certain activities thought to be too risky to the elder’s bodily health or to household order. Family members chose a restrictive approach to the elder’s activity choice instead of an assistive approach for multiple reasons, including: it was thought that the elder could not safely engage in the activity even with support, family members feared the elder might try to take up the activity when outside of supervision, or because family members were unwilling to provide support at the moment the elder sought out the activity due to a number of concerns, including workload burden. The study participants highlighted three forms of restrictive work: (1) adapting the material context of the living space, (2) using the elder’s short-term memory deficit as a resource, and (3) engaging in intra-delusional redirections.

In a first technique, family members adapted the material context of the living space to restrict the elder’s involvement in certain activities that had been deemed a threat to his or her safety. One family member adapted the kitchen to lower the risks that the elder faced by removing a certain item that the elder had misused several times in the past. She reported, “Now she can’t make coffee because [the container from the coffee maker] it’s glass, right? … If I don’t get it before her, she’ll put it on the stove or the gas burner. … She’s done that once or twice, and that’s not good. So now I hide it from her so she can’t find it…” Family members also adapted the material context of the living space by deploying barricades inside the home to restrict elders from entering areas where they could engage in risky activities without supervision, such as the kitchen, the garage, or the outside. One family, for instance, used a baby gate to limit the elder’s passage from the front to the back part of the house.

In a second technique, family members relied on the elder’s memory impairment as a resource in restricting his or her involvement in certain activities deemed unsafe. One common technique was to make false promises to re-engage later activities that elders were seeking to engage in now. By convincing the elder to engage in it later, family members hoped to increase the likelihood that he or she would forget about wanting to do it. The wife of a man with Alzheimer’s described her experience with this technique,

… [H]e drives his pick-up in the orchard and that’s the only place he is allowed to go. I don’t know if he remembers that he is not supposed to go anywhere else, because he sometimes says, “You know, I need to go get something,” and I say, “No, we don’t need that. We can go later if you don’t mind. Can we wait?” And he’ll say “okay.”

Family members also exploited the elder’s memory impairment by hiding objects that he or she needed in order to engage in risky activities in hopes that the individual would forget the purpose of the search for the item. The same wife quoted above described the process of keeping her husband from driving by hiding the keys to his truck and then playing dumb. The technique worked effectively, she noted, because he would soon forget that he was looking for them.

In a third technique, family members played along with active delusional episodes toward the goal of directing the elder away from a potentially risky activity or line of action. Commonly, these delusions are out of time episodes, or moments when the individual believes that he or she is temporally located at some moment in his or her own past and is seeking to engage in an activity that fits that time period, but not the current time period. In one case, for instance, the wife of a man with Alzheimer’s described her attempt to restrict her husband’s line of action pertaining to his decades-long job managing the irrigation of an orchard.

… [H]e gets me up in the middle of the night, and I ask him “What are you doing?” He says, “Well, I am going to go break the water.” I said, “There is no water,” and I get so, so frustrated. … [T]hen okay, “I tell you what. You go to bed. I’ll get Manuel on the phone, and tell him to go get the water for you.” He said, “Okay…” So I pretend I call Manuel…

In this instance, the wife affirmed her husband’s conception of reality in order to redirect him back to bed and away from a line of action that she perceived as potentially risky for him.

In sum, having lost the elder’s effective collaboration in avoiding or managing risky activities, family members developed and deployed unilateral autonomy management techniques. Through assistive techniques, family members helped elders engage in activities in ways thought to reduce risk. Through restrictive techniques, family members attempted to prevent elders from engaging in activities deemed too risky for their involvement even with support.

Discussion

This study charts the way families attempted to manage an individual’s growing incompetence in daily activities across the disease trajectory. It shows the role family members have in shaping the form that functional decline takes and thus, makes the larger point that dementia’s symptoms do not have a pure form that exists outside of social context. Rather, dementia’s expression as a disease entity always takes shape within a particular social context that constrains individuals to see it in a particular light and respond to it in particular ways.

The findings report that social support takes three sequentially-linked forms around functional decline. Early on in the disease progression, elders continued to seek engagement in decades-old activity preferences despite growing impairment (see Menne, Kinney, & Morhardt, 2002, for complementary findings). At this stage, elders were generally perceived as having awareness of their growing deficits, working collaboratively with family members to maintain functional ability in certain activities. As time passed, family members began to notice the elder’s declining awareness of these deficits. Through lay awareness tests and deliberation with other family members, they determined that the elder sometimes reverted back to a pre-disease conception of his/her own abilities and sought to engage in activities that he or she could no longer manage independently. Perception of declining deficit awareness by family members acted as a key turning point in how they related to elders and managed the disease, spurring them to modify their conception of the elder as a self-directed agent and develop a greater vigilance around the elder’s activity choices. Family members developed their own idiosyncratic techniques that assisted and restricted the elder’s autonomy to minimize risks. We describe the effort to use these techniques as autonomy management work.

Within the larger effort to manage symptoms, family members treated autonomy management work as a last line of defense against the symptoms of declining competence and deficit awareness. When these symptoms occurred despite using some combination of pharmacological and lay efforts to manage them, family members relied on autonomy management techniques to minimize the dangerous impact that they could have. In this way, autonomy management techniques complemented other symptom management measures, providing a buffer between elders and unsafe activities when symptom control proved impossible.

Elucidating the process by which family members managed growing incompetence sheds light on the important role of awareness perception in household dementia care. Currently, there exists an extensive literature examining clinical dimensions of declining deficit awareness or anosognosia, including its detection and measurement, especially for diagnostic purposes (Starkstein, Jorge, Mizrahi, & Robinson, 2006), cognitive correlates (Reed, Jagust, & Coulter, 1993) and the nature of its expression, including its fluctuations (Clare, 2004) and effects on self (Clare, 2003). Despite these research gains, there are currently few studies that address the impact that perceived anosognosia has on family caregiving and none that elucidate the social process by which it occurs. Related work, for instance, shows that anosognosia is associated with increased caregiver burden (Seltzer, 1997; Turró-Garriga et al., 2013).

The current study extends this area of research by showing the central role that lay perceptions of awareness play in efforts to manage growing incompetence in everyday activities. It explains the social mechanism by which the perception of declining awareness transforms care from a collaborative pursuit with the declining individual into a unilateral pursuit utilizing an array of tricks and ruses to influence the individual’s activity choices. The study’s naturalistic design helps show the importance of the interpretive process in assessing the household impact of a clinically-defined symptom, suggesting one reason why the clinical presence of anosognosia would not always translate into caregiver burden.

This study’s insight about the interpretive challenges that families encounter around deficit awareness holds important epistemological implications for a common clinical approach to identifying and measuring anosognosia. The approach measures deficit awareness using discrepancy scores generated by comparing the elder’s self-rated scores on daily functional abilities with the scores rated by a caregiver (see Mangone et al., 1991; Migliorelli et al., 1995). In this approach, the caregiver’s rating is treated as an accurate assessment and its discrepancy with the elder’s score reveals to what extent he or she is not aware of his or her own ability decline. The current study however, suggests that there can be problems with treating the caregiver’s report as fully reliable. The findings show that caregivers may sometimes have difficulty grasping an individual’s level of decline. First, family members themselves may suffer from a kind of courtesy anosognosia, a state in which they are unwilling or unable to admit to the extent of a loved one’s decline. Multiple family members in this study, for instance, reported that the individual’s decline was denied by others in the household when met with arguments or plausible evidence to the contrary.

Second, family members also signaled interpretive troubles by describing moments when elders employed a likely cover-up tactic to hide small errors in ability. They attempted to hide errors by taking issue with or showing nonchalance around what others defined as a “correct” procedure for accomplishing a task. In this way, affected individuals attempted to resist or redefine normative measures of successful activity engagement. One family member, for instance, suspected this maneuvering when her mom served her dad cold soup and claimed that he liked it that way. Another participant reported her dad’s nonchalance or apparent lack of care after she pointed out that he did not have to have coffee with the grounds in the coffee cup.

Facing a disease that is deeply stigmatized, individuals with Alzheimer’s have social and psychological reasons as to why they would hide their awareness of errors in ability from others (Clare, 2003; Sabat, 2002). Efforts taken to avoid acknowledging the disease’s effects, for instance, may signal the elder’s effort to protect him or herself from social and/or psychological injury (Clare, Roth, & Pratt, 2005; Sabat, 2002). While these interpretive obstacles pose challenges to using caregiver reports of ability level, this study suggests that to better understand the interpretive challenges that observers face and thus the reliability of observer reports, researchers must better understand the social process in which the interpretations are made. These findings call for more research around the interpretive challenges that proxy raters may encounter.

This study also helps situate the use of duplicity (and associated measures) in the social process of support around dementia. While researchers have highlighted the issue of duplicity in caregiving and the kinds of ethical dilemmas it can create (see Blum, 1994; Elvish, James & Milne, 2010; Strech, Mertz, Knüppel, Neitzke, & Schmidhuber, 2013), the current study identifies the turning point in the social process of care when family members began using duplicitous techniques. The evidence shows that they began using these techniques (identified herein as restrictive unilateral autonomy management techniques) as a self-conscious strategy when the elder’s awareness ability was thought to have declined severely enough to make transparent negotiation difficult. At this point in the progression of declining deficit awareness, family members found that elders were less capable of heeding their warnings and following their instructions for avoiding activities that had become too dangerous to pursue independently. At this stage, family members resorted to techniques that function as ruses to fool or trick elders away from risky activities.

This study has two important limitations. First, the participant sample is almost entirely made up of adult-children. It is likely that adult-children will experience a more protracted and potentially more risky transition period between collaborative and unilateral autonomy management work in contrast to spousal caregivers. Adult-children commonly must make decisions in concert with other siblings or family members. Negotiating with multiple members may raise the likelihood of disagreement and conflict that can delay a decision to curtail an elder’s independence when it is urgently needed. In addition, spouse caregivers likely will have spent many more years in close proximity with the affected individual and be better suited to notice minute, yet critical changes in the individual’s awareness level that can lead to timely changes in their autonomy management practices. Second, the participant sample only includes family members dealing with individuals who have one type of dementia: Alzheimer’s. While there are important differences in symptom behaviors between dementia sub-types (Bradshaw, Saling, Hopwood, Anderson, & Brodtmann, 2004; Chiu, Chen, Yip, Hua, & Tang, 2006), we believe that these results would extend to families dealing with vascular, Lewy body, and frontotemporal dementias. Future research can test the extent to which features of the autonomy management process identified within the Alzheimer’s context can effectively explain features of the support process around other forms of dementia.

This study reveals the social contextual factors that influence how family members identify and respond to growing signs of risk in an elder’s decades-old activities. Across the autonomy management process, family members attempted to balance their concerns of reducing risk with their concerns of permitting enough autonomy to promote wellbeing. In limiting an elder’s activities too much, for instance, they feared they could reduce his or her chances of finding spontaneous sources of meaningful engagement and potentially cause friction within their relationship. Yet in limiting their activities too conservatively, family members feared they could inadvertently permit elders to injure themselves and possibly others. Autonomy management provides a useful conceptual framework for understanding how family members adjusted their measures to deal with this dynamic as the disease advanced.

Diagram 1.

The Autonomy Management Process around Functional Decline at Home

Research Highlights.

Investigates how US families manage the household risks of Alzheimer’s disease

Explains how the autonomy management process occurs across three stages.

Identifies perception of declining deficit awareness as important turning point.

Reveals the social context of interpretive work around awareness and risk.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Brandon Berry, Email: blberry@ucdavis.edu.

Ester Carolina Apesoa-Varano, Email: apesoavarano@ucdavis.edu.

Yarin Gomez, Email: yargomez@ucdavis.edu.

Works Cited

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Association Report: 2012 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 8(2):131–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HS. Tricks of the trade: How to think about your research while you’re doing it. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Berry B. Minimizing confusion and disorientation: Cognitive support work in informal dementia caregiving. Journal of Aging Studies. 2014;30:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard RL, Fox PJ. Resisting social disenfranchisement: Negotiating collective identities and everyday life with memory loss. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(7):1509–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum NS. The management of stigma by alzheimer family caregivers. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 1991;20(3):263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Blum NS. Deceptive practices in managing a family member with alzheimer's disease. Symbolic Interaction. 1994;17(1):21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw J, Saling M, Hopwood M, Anderson V, Brodtmann A. Fluctuating cognition in dementia with lewy bodies and alzheimer's disease is qualitatively distinct. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):382–387. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2002.002576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas C. Projections of alzheimer's disease in the united states and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88(9):1337–1342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn F, Goodman C, Sworn K, Rait G, Brayne C, Robinson L, Iliffe S. Psychosocial factors that shape patient and carer experiences of dementia diagnosis and treatment: A systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9(10):e1001331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu MJ, Chen TF, Yip PK, Hua MS, Tang LY. Behavioral and psychologic symptoms in different types of dementia. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2006;105(7):556–562. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisp TAC, Tabberer S, Thomas BD. Bounded autonomy in deciding to seek medical help: Carer role, the sick role and the case of dementia. Journal of Health Psychology. 2013;18(2):272–281. doi: 10.1177/1359105312437265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L. Developing awareness about awareness in early-stage dementia. the role of psychosocial factors. Dementia. 2002;1(3):295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Clare L. Managing threats to self: Awareness in early stage alzheimer's disease. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(6):1017–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Roth I, Pratt R. Perceptions of change over time in early-stage alzheimer's disease: Implications for understanding awareness and coping style. Dementia. 2005;4(4):487–520. [Google Scholar]

- Clare L. Awareness in people with severe dementia: Review and integration. Aging and Mental Health. 2010;14(1):20–32. doi: 10.1080/13607860903421029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare L, Rowlands J, Bruce E, Surr C, Downs M. 'I don't do like I used to do': A grounded theory approach to conceptualising awareness in people with moderate to severe dementia living in long-term care. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(11):2366–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, Nolan M. 'Making the best of things': Relatives' experiences of decisions about care-home entry. Ageing & Society. 2003;23(4):429–450. [Google Scholar]

- Elvish R, James I, Milne D. Lying in dementia care: An example of a culture that deceives in people's best interests. Aging & Mental Health. 2010;14(3):255–262. doi: 10.1080/13607861003587610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everard K, Lach H, Fisher E, Baum C. Relationship of activity and social support to the functional health of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55:S208–S212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.s208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Smith RW. Alzheimer's disease victims: The “unbecoming” of self and the normalization of competence. Sociological Perspectives. 1989;32(1):35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing Co; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood T. Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mangone CA, Hier DB, Gorelick PB, Ganellen RJ, Langenberg P, Boarman R, Dollear WC. Impaired insight in alzheimer's disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 1991;4(4):189–193. doi: 10.1177/089198879100400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren AN, LaMantia MA, Callahan CM. Systematic review of non14 pharmacologic interventions to delay functional decline in community-dwelling patients with dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 2013;17(6):655–666. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.781121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, Kinney JM, Morhardt DJ. 'Trying to continue to do as much as they can do': Theoretical insights regarding continuity and meaning making in the face of dementia. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice. 2002;1(3):367–382. [Google Scholar]

- Menne HL, Tucke SS, Whitlatch CJ, Feinberg LF. Decision-making involvement scale for individuals with dementia and family caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias. 2008;23(1):23–29. doi: 10.1177/1533317507308312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliorelli R, Tesón A, Sabe L, Petracca G, Petracchi M, Leiguarda R, Starkstein SE. Anosognosia in alzheimer's disease: A study of associated factors. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1995;7(3):338–344. doi: 10.1176/jnp.7.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyle W, Venturto L, Griffiths S, Grimbeek P, McAllister M, Oxlade D, Murfield J. Factors influencing quality of life for people with dementia: A qualitative perspective. Aging and Mental Health. 2011;15(8):970–977. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.583620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oulton K, Heyman B. Devoted protection: How parents of children with severe learning disabilities manage risks. Health, Risk & Society. 2009;11(4):303–319. [Google Scholar]

- Perry J, O'Connor D. Preserving personhood: (re)membering the spouse with dementia. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2002;51(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney A. Family strategies for supporting involvement in meaningful activity by persons with dementia. Journal of Family Nursing. 2006;12(1):80–101. doi: 10.1177/1074840705285382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney A, Chaudhury H, O'Connor DL. Doing as much as I can do: The meaning of activity for people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health. 2007;11(4):384–393. doi: 10.1080/13607860601086470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popham C, Orrell M. What matters for people with dementia in care homes. Aging & Mental Health. 2012;16(2):181–188. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.628972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed BR, Jagust WJ, Coulter L. Anosognosia in alzheimer's disease: Relationships to depression, cognitive function, and cerebral perfusion. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1993;15(2):231–244. doi: 10.1080/01688639308402560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabat S. The experience of Alzheimer’s disease: life through a tangled veil. Oxford: Blackwell; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sabat SR. Epistemological issues in the study of insight in people with alzheimer's disease. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice. 2002;1(3):279–293. [Google Scholar]

- Samsi K, Manthorpe J. Everyday decision-making in dementia: Findings from a longitudinal interview study of people with dementia and family carers. International Psychogeriatrics. 2013;25(6):949–961. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer B. Awareness of deficit in alzheimer's disease: Relation to caregiver burden. Gerontologist. 1997;37(1):20–24. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, Robinson RG. A diagnostic formulation for anosognosia in alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2006;77(6):719–725. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.085373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strech D, Mertz M, Knüppel H, Neitzke G, Schmidhuber M. The full spectrum of ethical issues in dementia care: Systematic qualitative review. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;202(6):400–406. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans S, Tavory I. Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory. 2012;30(3):167–186. [Google Scholar]

- Tschanz JT, Piercy K, Corcoran CD, Fauth E, Norton MC, Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG. Caregiver coping strategies predict cognitive and functional decline in dementia: The cache county dementia progression study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turró-Garriga O, Garre-Olmo J, Vilalta-Franch J, Conde-Sala JL, Gracia Blanco M, et al. Burden associated with the presence of anosognosia in alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;28(3):291–297. doi: 10.1002/gps.3824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, Scanlan JM. Is caregiving hazardous to one's physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(6):946–972. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wackerbarth SB. The alzheimer's family caregiver as decision maker: A typology of decision styles. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2002;21(3):314–332. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Robert S. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. New York: Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wenborn J, Challis D, Head J, Miranda-Castillo C, Popham C, Thakur R, Orrell M. Providing activity for people with dementia in care homes: A cluster randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;28(12):1296–1304. doi: 10.1002/gps.3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]