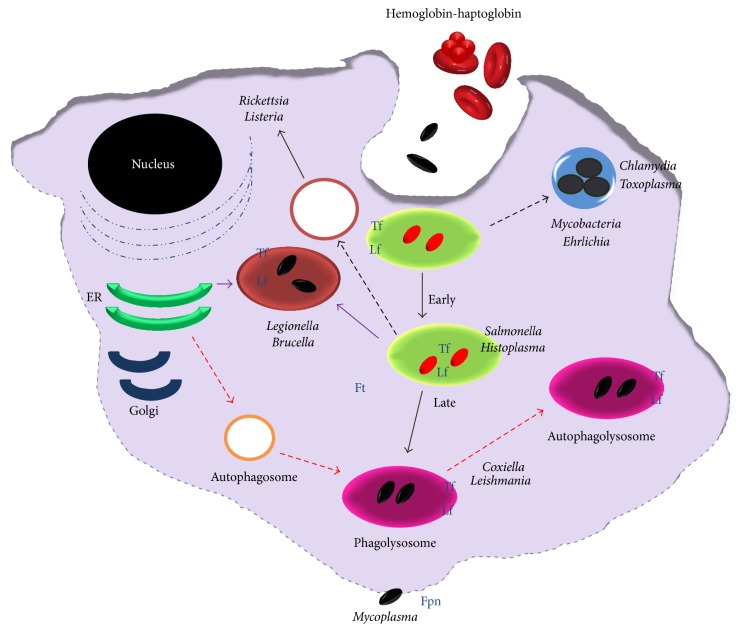

Figure 2.

Intracellular parasites and iron sources inside of the macrophage. During infection with intracellular bacteria, iron is required by both the host cell and the pathogen that inhabits the host cell. Macrophages require iron as a cofactor for the execution of important antimicrobial effector mechanisms, and so forth. On the other hand, intracellular bacteria also have an obligate requirement for iron to support their growth and survival inside cells. Some pathogens are internalized into membranous compartments (endosomes/phagosome) and then subsequently trafficked to the lysosome for degradation. Intracellular pathogens have evolved specific mechanisms to survive within this intracellular environment, for example, Salmonella persists in the endocytic pathway, and others escape the endo-/lysosomal system and exist in the cytosol. Other bacteria remain within a membranous envelope that may be a modified version of the endoplasmic reticulum (L. pneumophila) or a membranous compartment generated by the bacteria (Chlamydia), and so forth. Intracellular pathogens can acquire iron because macrophages contain iron-proteins such as transferrin, lactoferrin, ferritin, hemopexin, hemoglobin, or hemoglobin-haptoglobin complexes, in its different compartments.