Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

This pilot investigation utilized experimental techniques that were developed and refined in the field of exercise physiology and superimposed techniques that are considered to be best-practice in the field of analgesic research.

Key words: Delayed onset muscle soreness, DOMS, Diclofenac; Topical NSAIDS, Analgesic methodology, Analgesic clinical trials

Abstract

Based on a thorough review of the available literature in the delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) model, we identified multiple study design characteristics that are considered to be normative in acute pain research but have not been followed in a majority of published DOMS experiments. We designed an analgesic investigation using the DOMS model that both complied with current scientifically accepted standards for the conduct of analgesic studies and demonstrated reasonable assay sensitivity. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled within-subject study compared the efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium 1% with a matching placebo in reducing pain associated with DOMS. After exercise, subjects reporting DOMS received topical diclofenac sodium gel 1% (DSG 1%) applied to one leg and placebo to the other every 6 hours for 48 hours. Pain intensity was assessed at rest, upon standing, and when walking in the 48 hours after initial drug application (T0). The primary end point was the reduction in pain intensity (SPID 24) on walking. Subjects receiving DSG 1% had less pain while walking compared with those receiving placebo at 24 hours (SPID 24 = 34.9 [22.9] and 23.6 [19.4], respectively; P = 0.032). This investigation used experimental techniques that have been vetted in the field of exercise physiology and superimposed techniques that are considered to be best practice in the field of analgesic research. Over time and with the help of colleagues in both fields of study, similar investigations will validate design features that impact the assay sensitivity of analgesic end points in DOMS models. In addition, the study confirmed the analgesic efficacy of topical DSG 1% over placebo in subjects experiencing DOMS.

1. Introduction

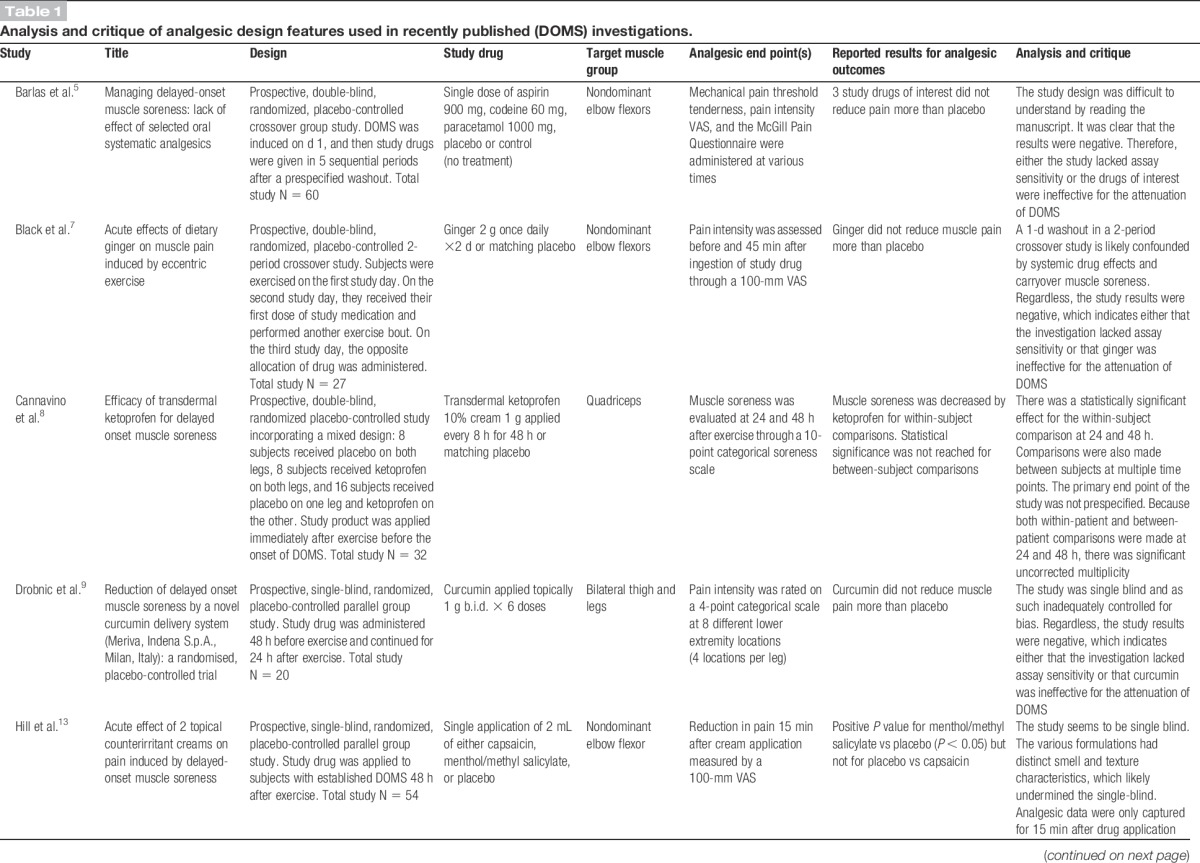

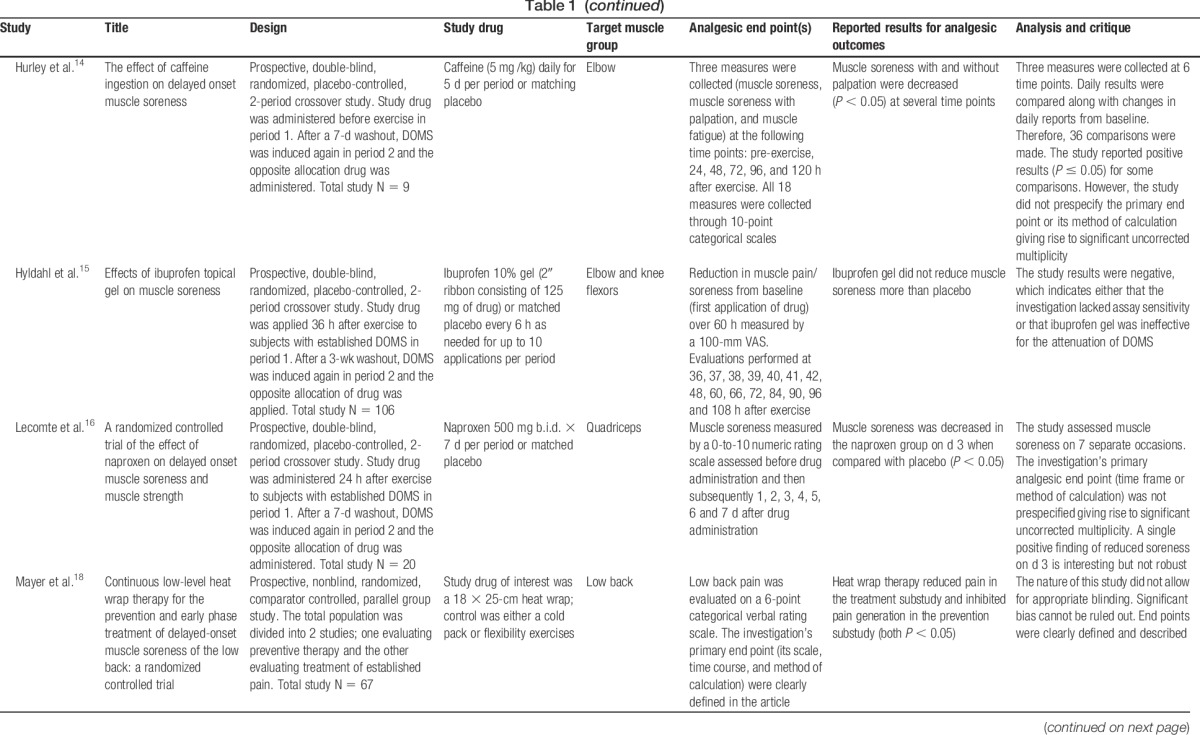

Delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) is an important experimental model and clinical pain state that has been used extensively to evaluate the analgesic efficacy of various oral drugs, topical agents, and devices.8,13,18,19,24,26 Most published DOMS studies primarily report physiologic (strength, swelling, metabolic rate, and range of motion) and laboratory (creatinine kinase, leukocyte infiltration, and immunohistochemistry) end points.5,9,18,23,26 Analgesic end points (muscle pain and/or muscle soreness) are also assessed in some of these published studies.7,8,19,25 Based on our review of the literature, we assert that although most published DOMS investigations have been well designed to evaluate physiologic and laboratory end points, they have not been optimally designed to evaluate analgesic end points. In Table 1, we select, analyze, and critique the analgesic design features of 15 high-quality recently published DOMS investigations.

Table 1.

Analysis and critique of analgesic design features used in recently published (DOMS) investigations.

Pain is a subjective end point that is measured by a variety of scales. Analgesic study outcomes are reported using an assortment of calculations derived from these scales. It is therefore critical that analgesic investigations prespecify the following: (1) a primary end point, (2) the scale that will be used to measure that primary end point, and (3) the method by which the significance of that primary end point will be calculated.2 However, several recently published DOMS investigations do not comply with this requirement (Table 1).8,14,16,19,23,25,26 Studies that report positive analgesic outcomes but have not clearly prespecified how those outcomes will be evaluated are subject to type I error (falsely positive conclusions).

Recently published DOMS investigations may also have issues with type II error (falsely negative conclusions) secondary to low assay sensitivity. A study's assay sensitivity is defined as its ability to detect a treatment difference between an efficacious drug and placebo. There have been several DOMS studies on drugs with known efficacy or on drug reformulations (with presumed efficacy) that nevertheless have reported negative analgesic findings (Table 1).5,15,22 Negative study results can then be explained either as true negatives (the study product in the question does not work to treat DOMS) or false negatives (the study product works but the investigation lacks the assay sensitivity to detect a treatment effect).

Our hypothesis was that, in general, the latter was true; the high rate of negative findings in the DOMS model was secondary to nonoptimal analgesic study design and conduct. We identified multiple study design characteristics that are considered to be normative in acute surgical pain research that were not incorporated into a majority of recently conducted DOMS investigations. Specific examples include the following: (1) protocol-mandated baseline entry criteria requiring moderate or severe pain before randomization, (2) study-masking procedures to ensure that subjects were unaware of the baseline pain intensity values required for study entry, (3) attempts to control the placebo response, and (4) domiciling of subjects in research units where experimental controls (ie, dosing compliance, diary compliance, restricted ambulation) can be closely monitored during the primary efficacy evaluation period.

The purpose of this pilot study, then, was to attempt to design an analgesic investigation using the DOMS model that (1) controlled for type I error by complying with scientifically accepted standards of conduct for analgesic studies and (2) controlled for type II error by using vetted study design characteristics that are known to increase the assay sensitivity of acute surgical pain investigations. The pilot was designed after a thorough literature review, during which we were unable to locate any published peer-reviewed articles discussing analgesic methodological best practices relevant to DOMS.

To assess the assay sensitivity (risk of type II error) of our model, we selected diclofenac sodium topic gel 1% (DSG 1%, Voltaren Gel1, Novartis Consumer Healthcare, Inc., Parsippany, NJ) as our study drug of interest and compared it with placebo. Topical DSG 1% is an agent with known analgesic efficacy that is approved in the United States for the treatment of pain associated with osteoarthritis.3,4 We therefore assumed that DSG 1% would have the ability to demonstrate analgesic efficacy in a DOMS model if appropriate study design characteristics were selected. To control for type I error, the primary end point of this pilot investigation was (1) prespecified, (2) measured using a validated 11-point numeric pain intensity scale, and (3) calculated using a well-understood efficacy paradigm (SPID 24).

2. Methods

2.1. Approvals and disclosures

Before any study-related activities, the investigation and its supporting documents (protocol, informed consent form, investigator brochure, and recruitment materials) were reviewed and approved by Aspire Institutional Review Board (IRB) (San Diego, CA). The requisite information was then listed on Clinical Trials.gov (identifier: NCT02087748). Both the DSG 1% gel and the matching placebo were provided by Novartis Consumer Healthcare under an investigator-initiated research protocol and grant.

2.2. Study design and objectives

For the DOMS model under study, we selected the following design features: prospective, double blind, randomized, and placebo controlled. The analgesic efficacy of topical DSG 1% was compared with a matching placebo gel using a 1-period within-subject design. The prespecified primary efficacy end point of the study was the summed pain intensity difference (SPID) experienced by the subject while walking over the first 24 hours after drug application. The study also evaluated several secondary efficacy end points including SPID 24 and 48 at rest and upon walking.

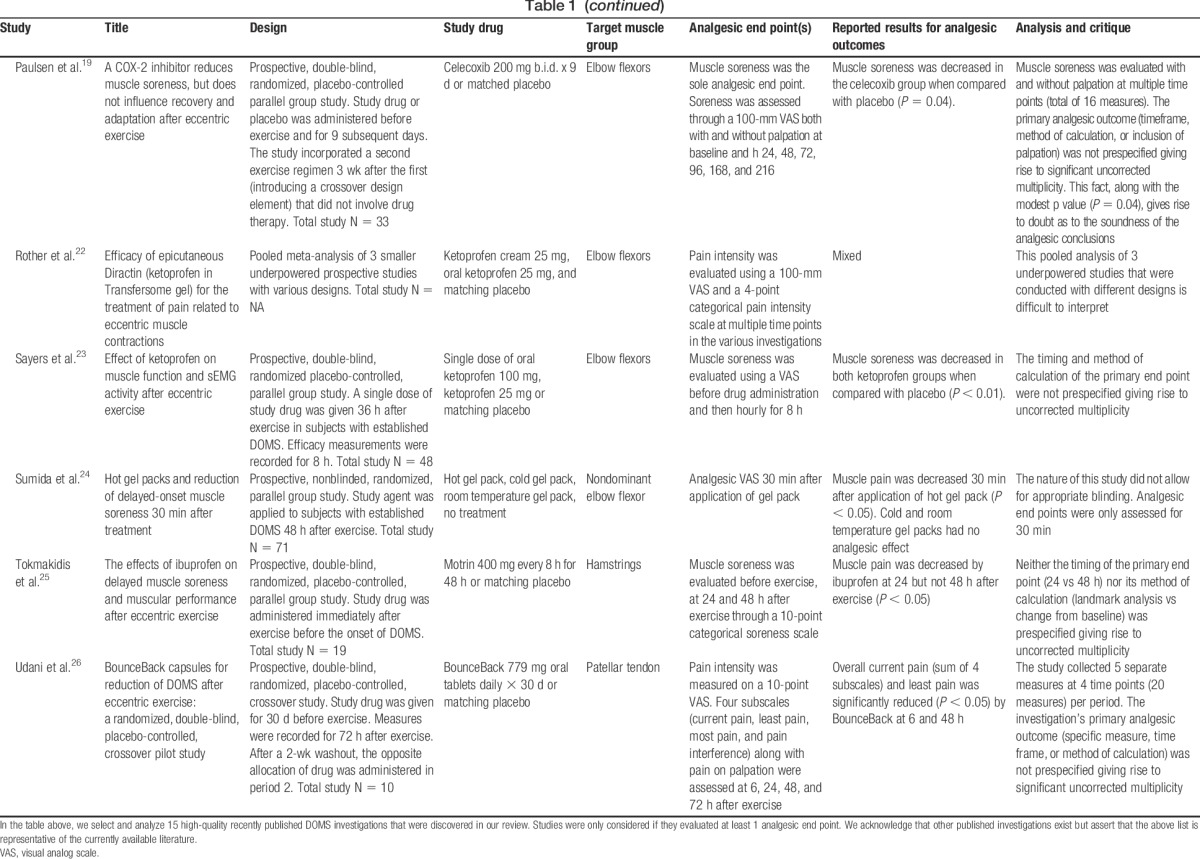

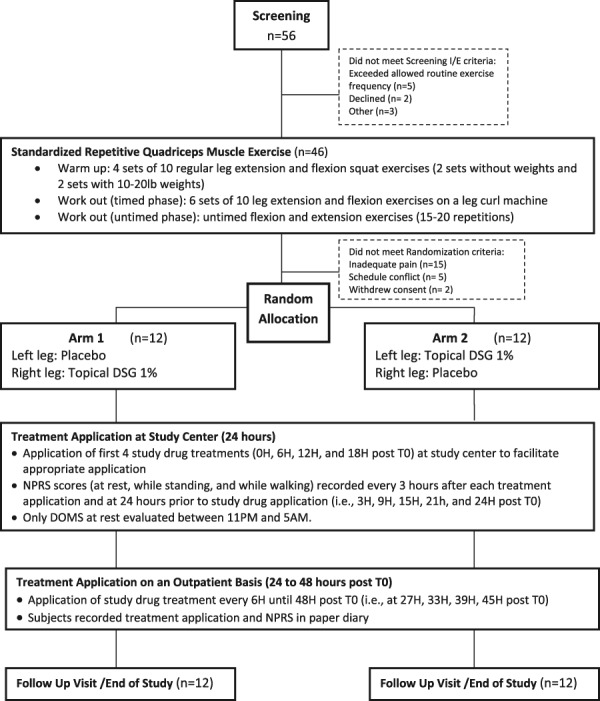

2.3. Investigational plan

This study included a total of 24 healthy volunteer subjects (Fig. 1). An initial screening visit was scheduled during which all subjects first signed written informed consent and then underwent a placebo response education program. The program included a 15-minute video series followed by a written examination designed to evaluate the study subject's understanding of the video modules. The key concepts covered in the video are described in Supplemental Table 1 (available online as Supplemental Digital Content at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A41), and a more detailed overview of the program is included in the Discussion section. The education process was followed by a physical examination, medical history, and inclusion/exclusion review. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study had to be met at 2 separate time points (Fig. 1). One set of selection criteria was used before exercise, and the other set was used to determine the extent of pain immediately before randomization (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram of the experiment. DOMS, delayed-onset muscle soreness; DSG 1%, diclofenac sodium gel 1%; T0, first study treatment application.

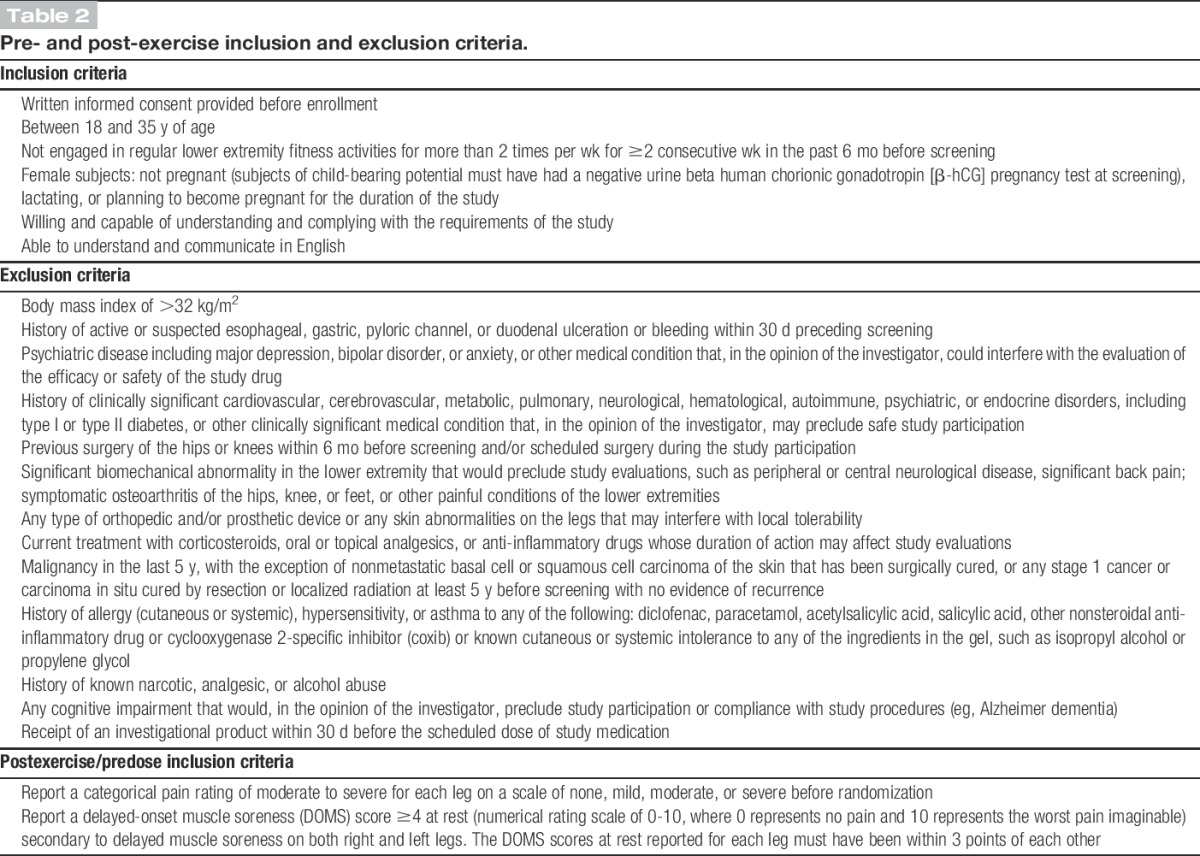

Table 2.

Pre- and post-exercise inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.4. Induction of delayed-onset muscle soreness

To create DOMS, all subjects performed a standardized repetitive quadriceps muscle exercise in 3 phases using a Body-Solid GCEC340 machine (Body-Solid, Inc, Forest Park, IL). The exercise regimen was modified from the protocol described by Cannavino et al.8 and is detailed below.

2.4.1. Warm-up and determination of maximum tolerated weight

Subjects completed a warm-up of 4 sets of 10 regular body weight squat exercises from standing position (2 sets without weights and 2 sets with approximately 10-20 lbs of weight). The maximum tolerated weight (MTW) on the leg curl machine was then determined for each leg by having the subject do a full extension and flexion with resistance (1 leg at a time) starting with a low but reasonable weight selected by the study staff and increasing it with every repetition until subjects reached their MTW. The MTW is defined as the highest weight under which a subject could perform a full extension and flexion.

2.4.2. Workout: timed phase

Starting with the dominant leg, subjects performed 6 sets of 10 leg extension and flexion exercises with each leg on the leg curl machine under 80% of the MTW for that leg. Each repetition was performed through the full pain-free range of motion in a slow controlled manner. Subjects performed the concentric portion of the repetition for 2 seconds, paused at full contraction for 1 second, and then completed the eccentric portion over a 4-second period (for a total of 7 seconds per repetition). Subjects performed each set as tolerated and were given a rest period of 1 to 2 minutes in between sets. Repetitions were performed until subjects were unable to move the weight load through the full range of motion. If subjects were unable to complete the full 6 sets under 80% MTW, the weight was decreased in 5 pound increments until subjects could no longer complete 60% MTW, or 6 sets were completed.

2.4.3. Workout: untimed phase

Subjects completed untimed flexion-and-extension exercises (15-20 repetitions) beginning with the last weight used in the timed phase. The weights were gradually decreased in increments of 5 pounds until no weight was used. The same protocol was then performed on the subject's opposite leg.

Subjects were asked to report to the study center within 24 to 48 hours after exercise, at which time categorical and numeric pain ratings were recorded. The postexercise inclusion criteria (Table 2) were based on the subject's pain scores at rest. To qualify, subjects (while at rest) needed to report a current categorical pain score of moderate or severe on a 4-point scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe) and a numerical pain intensity (NPRS: an 11-point numerical scale from 0 to 10 with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain imaginable) of ≥4. Both right and left legs needed to meet these criteria, and the NPRS scores for each leg had to be within 3 points of each other. Subjects were unaware of the specific postexercise analgesic inclusion criteria before randomization.

If subjects met all postexercise inclusion criteria, they were randomized to receive 4 g of topical DSG 1% applied to the right leg and matching placebo gel to the left leg or 4 g of topical DSG 1% applied to the left leg and matching placebo gel to the right leg. Because the study was double blinded, each subject received 2 identical tubes of gel, 1 with active topical DSG 1% and the other with placebo gel marked either “right” or “left”. Each application of the gel thereafter followed the treatment assignment. Before each dose, the subject palpated the point of maximal tenderness (PMT) on each anterior thigh. The area was then marked using a template with a cutout area of 400 cm2 centered over the PMT. The gels were applied to an area of 400 cm2 every 6 hours for 48 hours.

To minimize the placebo response, the subject (and not the study nurse) applied the investigational product to their own legs. The application procedure was however witnessed by study staff to ensure compliance. Placebo and active gel were indistinguishable visually, by feel or by smell. T0 was defined as the start time of the first application of study gel. Immediately after T0, 3 separate baseline pain intensity measures were recorded (NPRS at rest, while standing, and while walking).

Subjects were confined to the study center for 24 hours and then discharged home with a paper diary. The NPRS scores (at rest, while standing, and while walking) were measured at the following time points: 3, 9, 15, 21, and 24 hours after T0. To facilitate subject sleep, DOMS while standing and while walking were not collected between the hours of 11 pm and 5 am. Pain intensity at rest was assessed with the subject resting quietly for at least 5 minutes before each assessment. Subjects were then asked to stand and rate their worst pain caused by standing in each leg independently. Finally, subjects were asked to walk approximately 5 m (16 feet) at a moderate pace and then rated their worst pain caused by walking in each leg independently.

Subjects were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time and for any reason. Rescue medication was not permitted. Ancillary analgesic techniques such as ice, heat, and massage were also prohibited. After discharge from the research center, at approximately 24 hours after dosing, subjects were educated to continue application of study gel or placebo to each specified leg every 6 hours until 48 hours after initiation of treatment. A paper diary was provided for subjects to record drug application times and pain intensity scores at 27, 33, 39, 45, and 48 hours after T0. A follow-up visit was completed at 7 days (±1 day) after treatment initiation for end-of-study assessments.

Subjects completed a global assessment of analgesic efficacy for each leg at 24 hours, 48 hours, and the end-of-study visit. For this global assessment, subjects were asked to rate the study drug's efficacy as poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent for each leg separately. Safety was assessed through reports of spontaneous adverse events, medical history findings, and physical examination results.

2.5. Statistical methodology

The primary analysis of efficacy and safety end points used an intention-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all participants in the group who were randomized and had at least 1 treatment application. All 24 subjects completed the trial with no missing doses. The primary efficacy end point was the SPID from baseline experienced by the subjects while walking over the first 24 hours after initiation of treatment (SPID0-24). Secondary efficacy end points included SPID experienced over various time intervals while walking, at rest, or while standing. A complete statistical analysis plan was submitted to, and approved by, the Institutional Review Board before unblinding. Study drug was provided by Novartis Consumer Healthcare in a blinded fashion. The study center was not provided with the unblinded treatment code until after data lock was confirmed.

The following analyses were performed for all primary and secondary end points requiring SPID calculations:

(1) A SPID was calculated for each leg (SPID-DSG and SPID-placebo) by applying the trapezoidal rule to the pain intensity differences from baseline (PIDs) over the relevant time frame.

(2) For each subject, a difference in SPID values was calculated using the formula (SPID-DSG) − (SPID-placebo) = SPID-delta.

(3) The mean and SD of the SPID-deltas was calculated.

(4) Differences between the treatments (DSG vs placebo) were tested for all primary and secondary end points at the α = 0.05 level with 2-tailed paired t tests of the relevant SPID-delta values.

Because rescue therapy was not permitted and all 24 subjects completed the study, significant data imputation was not required. Missing assessments were primarily the result of subjects sleeping (the protocol mandated that only assessments at rest were to be performed between the hours of 11 pm and 5 am). These missing data were interpolated using a linear best fit approach.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

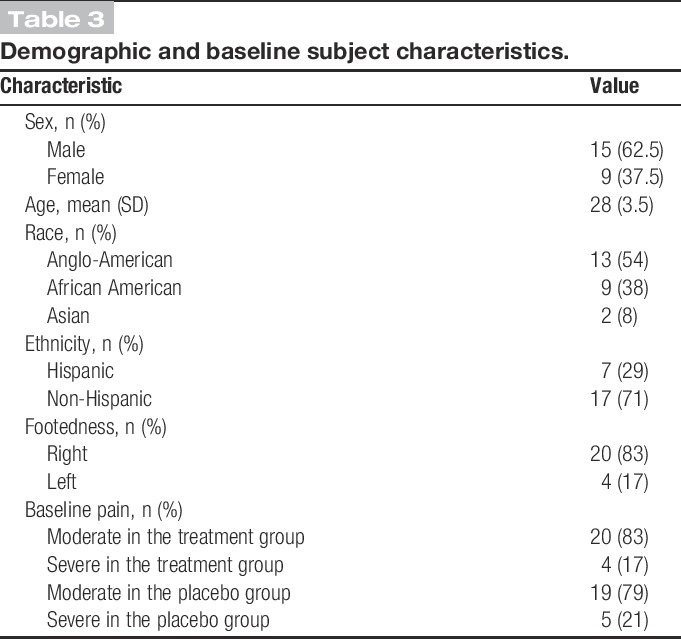

Subjects were recruited over 5 weeks (March 12, 2014 to April 18, 2014). Subject disposition is described in the consort flow diagram (Fig. 1). Demographic and baseline characteristics of the ITT population are summarized in Table 3. The population was essentially young and healthy (mean age, 28 ± 3.5) without significant concomitant disease or medication intake. The distribution was approximately 2:1 male to female. At baseline, slightly more than 80% of subjects described their baseline pain intensity as “moderate.” The remaining subjects described their initial pain as “severe.” In most cases, subjects described a comparable level of pain in both legs.

Table 3.

Demographic and baseline subject characteristics.

3.2. Efficacy and safety assessments

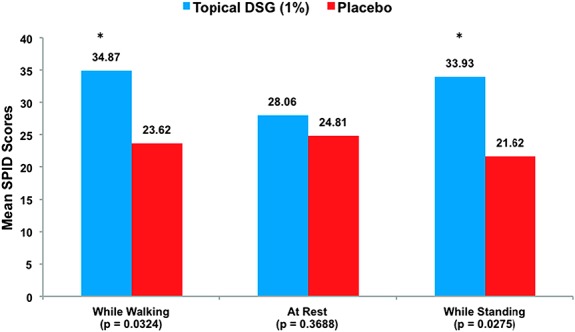

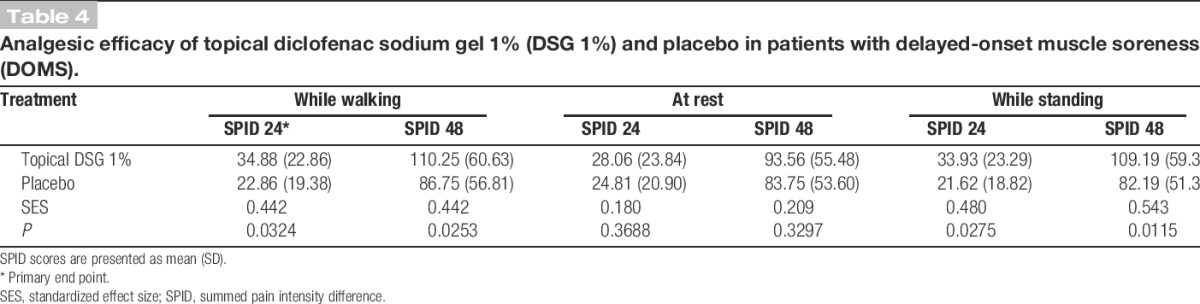

The primary end point of the study (SPID0-24 while walking) showed positive results. Subjects reported that legs receiving topical DSG 1% had a greater mean SPID score (ie, less pain) compared with those receiving placebo at 24 hours (34.9 vs 23.6, respectively; Student t test P = 0.032; SES = 0.442), suggesting good experimental assay sensitivity (Fig. 2 and Table 4).

Figure 2.

Mean SPID scores in subjects with delayed-onset muscle soreness over the first 24 hours after drug application (SPID0-24). *P < 0.05.

Table 4.

Analgesic efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium gel 1% (DSG 1%) and placebo in patients with delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS).

Multiple secondary efficacy end points (listed in Table 4) were also assessed. The mean SPID score between the DSG 1% group compared with the placebo group was statistically significant while walking at 48 hours (110.3 vs 86.8, respectively; Student t test P = 0.025) (Fig. 2). At rest, the difference in the mean SPID scores in subjects receiving topical DSG 1% compared with subjects receiving placebo at 24 hours was not statistically significant (28.1 vs 24.8, respectively; Student t test P = 0.369) (Fig. 2). Similarly, the difference in the mean “at rest” SPID scores at 48 hours was not significant (93.6 vs 83.8, respectively; Student t test P = 0.330). However, the difference in mean SPID scores between the treatment groups while standing was statistically significant at both 24 hours and 48 hours (33.9 vs 21.6 at 24 hours and 109.2 vs 82.2 at 48 hours; Student t test P = 0.028 at 24 hours and P = 0.012 at 48 hours).

Safety assessments were gathered by collecting all observed or reported adverse events and by examining the site of drug application. The exercise regimen, subsequent reversible muscle injury, and topical DSG 1% were well tolerated by all subjects. No subjects experienced any rash, irritation, or other adverse events during the study.

4. Discussion

The selected methodology for this pilot study demonstrated very good assay sensitivity, resulting in a positive P value with only 24 subjects. It is difficult to determine which specific design elements contributed to the success of the study. To properly evaluate this question, it would be necessary to perform multiple studies changing only 1 design element at a time, while measuring the effect of that change on the investigation's effect size. In the absence of this knowledge, we provide a discussion below with our opinions as to design elements that may have positively impacted experimental assay sensitivity. The purpose of providing these opinions is not to assert the effectiveness of any specific technique, but rather to begin a scientific discussion regarding the analgesic methodology of DOMS studies.

As previously stated, subjects were required to view a placebo response video education program before entering the trial. Analgesic studies on topical agents typically have reported high placebo response rates. This may be secondary to the physical effect of rubbing gel or cream onto the subject's body.12 In our model, the placebo response rate was low enough to allow good assay sensitivity. Details regarding the placebo response video course are presented in Supplemental Table 1 (available online as Supplemental Digital Content at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A41). After watching the video, subjects were required to take a written examination. Test materials included (1) factual questions about study end points, (2) conceptual questions dealing with bias, investigator motivation, and subject motivation, and (3) real-world study vignettes. After subjects completed the exam, the test was graded and subjects were required to correct any errors. A predefined passing score was not set. Rather, the purpose of the examination was to stimulate a dialog between the investigator and subject regarding the study purpose, end points, and bias. If, based on this dialog, the investigator felt that the subject did not or could not comprehend critical study factors, the investigator had the discretion to screen-fail the subject (discretion was granted per protocol a priori). Subjects were trained at screening (with both video and test) and again on the day of randomization before T0 (video only).

The within-subject design used for this study doubled the sample size without a significant increase in the time or cost required to conduct the study. Most crossover studies require a 2-period design, which means that subject time commitment and research center resources are doubled. Because our design used both legs simultaneously, resource allocation required to increase the number of legs evaluated (from 24 legs to 48 legs) was fairly limited. Additionally, within-subject designs have been suggested to reduce intrasubject variability and may reduce the placebo response.6,8,21 Our theory regarding placebo response was that subject expectation may have been controlled by ensuring that the subject was aware that 1 leg was treated with an active drug whereas the other was not. High subject expectation leads to a placebo response.10

A study performed by Cannavino et al.8 simultaneously used a within-subject and between-subject design (Table 1). Their findings indicated that a within-subject design had far greater assay sensitivity than did a between-subject design. Our experiment was therefore modeled after the within-subject portion of the Cannavino study. Because DSG 1% was expected to have a local effect rather than a systemic effect, this design seemed appropriate. It is important to note, however, that a 1-period within-subject design is not feasible for most drugs (ie, systemically administered medications or topical agents with significant absorption and the potential for carryover effects).

In acute pain research, it is well documented that assay sensitivity is increased by randomizing only subjects who report moderate or severe pain.11,20 In this pilot, our postexercise criteria mandated that subjects report at least moderate pain at rest. Although our primary end point measured pain on walking (not at rest), we hypothesized that subjects who had moderate pain at rest might have a more robust pain state that is less susceptible to a placebo response and more amenable to a positive treatment response.

Significant care was taken to ensure that subjects were not aware of the specific postexercise analgesic criteria required for study entry. Because subjects received a stipend for study participation (and the specific amount was prorated based on the length of their study involvement), we attempted to ensure that reported postexercise entry scores were not manipulated by secondary motivations. If subjects inquired regarding the specifics of the requisite analgesic baseline entry criteria, study staff was instructed to respond as follows: “There are several baseline criteria that you must meet after exercise in order to qualify for continued study participation, but we are not allowed to disclose them.”

Selection of a primary end point that included pain upon movement (either pain while walking or while standing) as opposed to pain at rest seems to be an important design element for the maintenance of assay sensitivity. We observed a smaller effect size for pain at rest than for pain with movement (Table 4). It is probable that pain at rest is too mild to allow discrimination of analgesic effect. Pain while standing and while walking seem to have comparable assay sensitivity.

Subjects were housed at the research unit for the first 24 hours after drug application. Although subjects are domiciled within the research facility, experimental controls can be closely monitored. For example, ambulation can be regimented, correct dosing procedures and times can be observed, and assessments can be performed at verified times using verified mechanisms. It is probable that subject domiciling during the period of primary end point data capture augments an investigation's assay sensitivity.

The exercise regimen is obviously a key component of any DOMS study. We found that the existing literature is replete with meticulously coordinated exercise programs designed to produce reversible muscle injury in a consistent, safe, and reproducible manner.9,17 The degree of trauma measured by physiologic and laboratory end points is documented in several high-quality experiments. Because our 1-period within-subject design was intended to replicate a portion of Cannavino's experiment, we used an exercise regimen modeled after the program described in that article.8

5. Conclusions

This pilot investigation used experimental techniques that were developed and refined in the field of exercise physiology and superimposed techniques that are considered to be best practice in the field of analgesic research. The model exhibited excellent assay sensitivity and was safely conducted over a short period of time. Over time and with the help of colleagues in both fields of study, similar investigations will validate design features that impact the assay sensitivity of analgesic end points in DOMS models.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors, with the exception of Dr Desjardins, are full-time employees of Lotus Clinical Research, LLC (an analgesic research site and CRO). Dr N. Singla has received grants from Novartis Consumer Health, Inc, for consulting in the performance of clinical investigations. Dr Desjardins serves as an independent clinical research consultant to Lotus Clinical Research and to Novartis Consumer Healthcare. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This investigator-initiated study was supported through a grant from Novartis Consumer Health, Inc.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplemental Digital Content

Supplemental Digital Content associated with this article can be found online at http://links.lww.com/PAIN/A41.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.painjournalonline.com).

References

- [1].Voltaren Gel (Diclofenac Sodium Topical Gel) 1%. Available at: www.voltarengel.com/common/pdf/Voltaren-PI-10-19.pdf. Accessed October 2009.

- [2].Guidance for industry-analgesic indications: developing drug and biological products: services HaH. Rockville, Maryland: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), Food and Drug Administration, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Altman RD, Dreiser RL, Fisher CL, Chase WF, Dreher DS, Zacher J. Diclofenac sodium gel in patients with primary hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2009;36:1991–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Baraf HS, Gloth FM, Barthel HR, Gold MS, Altman RD. Safety and efficacy of topical diclofenac sodium gel for knee osteoarthritis in elderly and younger patients: pooled data from three randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, multicentre trials. Drugs Aging 2011;28:27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Barlas P, Craig JA, Robinson J, Walsh DM, Baxter GD, Allen JM. Managing delayed-onset muscle soreness: lack of effect of selected oral systemic analgesics. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:966–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barlow DH, Hayes SC. Alternating treatments design: one strategy for comparing the effects of two treatments in a single subject. J Appl Behav Anal 1979;12:199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Black CD, O'Connor PJ. Acute effects of dietary ginger on muscle pain induced by eccentric exercise. Phytother Res 2010;24:1620–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cannavino CR, Abrams J, Palinkas LA, Saglimbeni A, Bracker MD. Efficacy of transdermal ketoprofen for delayed onset muscle soreness. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:200–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Drobnic F, Riera J, Appendino G, Togni S, Franceschi F, Valle X, Pons A, Tur J. Reduction of delayed onset muscle soreness by a novel curcumin delivery system (Meriva®): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2014;11:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Haour F. Mechanisms of the placebo effect and of conditioning. Neuroimmunomodulation 2005;12:195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hartrick CT. Quality assessment in clinical trials: considerations for outcomes research in interventional pain medicine. Pain Pract 2008;8:433–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Heyneman CA, Lawless-Liday C, Wall GC. Oral versus topical NSAIDs in rheumatic diseases: a comparison. Drugs 2000;60:555–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].JMaS HKD. Acute effect of 2 topical counterirritant creams on pain induced by delayed onset muscle soreness. J Sport Rehabil 2002;11:202–8. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hurley CF, Hatfield DL, Riebe DA. The effect of caffeine ingestion on delayed onset muscle soreness. J Strength Cond Res 2013;27:3101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hyldahl RD, Keadle J, Rouzier PA, Pearl D, Clarkson PM. Effects of ibuprofen topical gel on muscle soreness. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lecomte JM, Lacroix VJ, Montgomery DL. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of naproxen on delayed onset muscle soreness and muscle strength. Clin J Sport Med 1998;8:82–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Malm C, Sjodin TL, Sjoberg B, Lenkei R, Renstrom P, Lundberg IE, Ekblom B. Leukocytes, cytokines, growth factors and hormones in human skeletal muscle and blood after uphill or downhill running. J Physiol 2004;556:983–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mayer JM, Mooney V, Matheson LN, Erasala GN, Verna JL, Udermann BE, Leggett S. Continuous low-level heat wrap therapy for the prevention and early phase treatment of delayed-onset muscle soreness of the low back: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87:1310–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Paulsen G, Egner IM, Drange M, Langberg H, Benestad HB, Fjeld JG, Hallen J, Raastad T. A COX-2 inhibitor reduces muscle soreness, but does not influence recovery and adaptation after eccentric exercise. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20:e195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Price DD, Bush FM, Long S, Harkins SW. A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. PAIN 1994;56:217–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Robey RR, Schultz MC, Inner CA. Single-subject clinical outcome research: designs, data, effect sizes and analyses. Aphasiology 1999;13:445–73. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rother M, Seidel EJ, Clarkson PM, Mazgareanu S, Vierl U, Rother I. Efficacy of epicutaneous Diractin (ketoprofen in Transfersome gel) for the treatment of pain related to eccentric muscle contractions. Drug Des Deval Ther 2009;3:143–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sayers SP, Knight CA, Clarkson PM, Van Wegen EH, Kamen G. Effect of ketoprofen on muscle function and sEMG activity after eccentric exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;33:702–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sumida KD, Greenberg MB, Hill JM. Hot gel packs and reduction of delayed-onset muscle soreness 30 minutes after treatment. J Sport Rehabil 2003;12:221–8. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tokmakidis SP, Kokkinidis EA, Smilios I, Douda H. The effects of ibuprofen on delayed muscle soreness and muscular performance after eccentric exercise. J Strength Cond Res 2003;17:53–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Udani JK, Singh BB, Singh VJ, Sandoval E. BounceBack capsules for reduction of DOMS after eccentric exercise: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2009;6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.