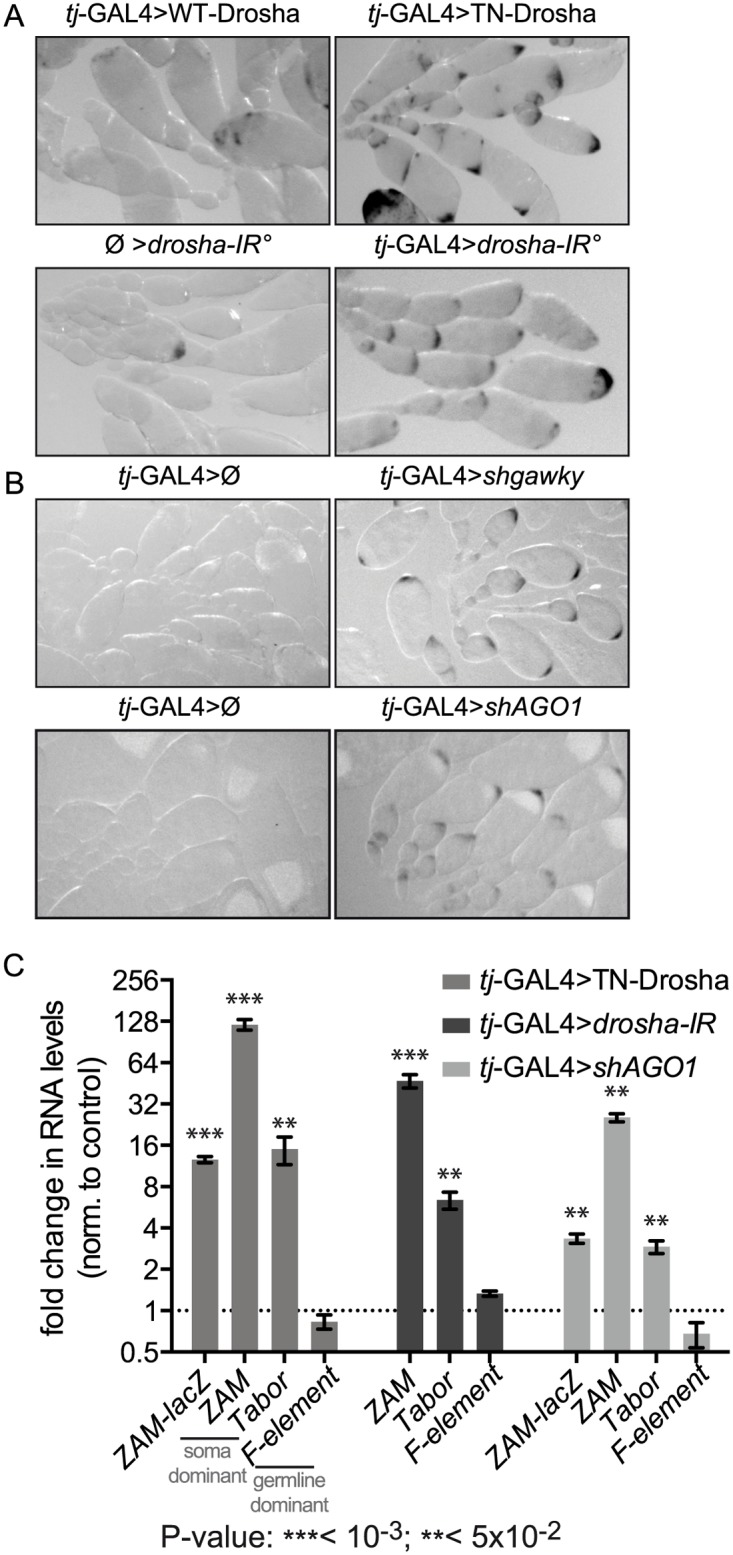

Fig 1. Follicle cell-specific defects in the miRNA pathway lead to ZAM-lacZ reporter and somatic TE de-repression.

(A) Comparison of ZAM-lacZ reporter expression in control ovaries in which WT-Drosha expression is driven by the tj-GAL4 somatic driver (tj-GAL4>WT-Drosha) or that contain two independent hairpins against Drosha without any driver (Ø>drosha-IR°) and in ovaries in which tj-GAL4 drives the expression of the trans-dominant negative Drosha construct (tj-GAL4>TN-Drosha) or the two Drosha long hairpins (tj-GAL4>drosha-IR°). The blue β-Gal staining is shown in black. (B) Comparison of ZAM-lacZ reporter expression in ovaries where gawky (tj-GAL4>shgawky) or AGO1 (tj-GAL4>shAGO1) were silenced by tj-GAL4-induced shRNA expression, and in ovaries from the respective sibling controls (tj-GAL4>Ø). The blue β-Gal staining is shown in black. (C) Fold changes in the steady-state RNA levels of the ZAM-lacZ reporter (PCR1 primer pair, S3 Table, Fig 2A), the somatic TEs ZAM and Tabor and the germline-specific TE F-element, following the expression, in follicle cells, of the trans-dominant negative Drosha construct (tj-GAL4>TN-Drosha), the Drosha long hairpins (tj-GAL4>drosha-IR) or the AGO1 small hairpin (tj-GAL4>shAGO1). In tj-GAL4>Drosha-IR ovaries, the ZAM-lacZ reporter was replaced by the UAS-dcr2 transgene (see S2 Table). Quantification was done relative to RpL32 and normalized to the respective controls (tj-GAL4>Ø, Ø>drosha-IR and tj-GAL4>shAGO3) (error bars represent the standard deviation (S.D.) of three biological replicates, log2 scale).