Abstract

Anti-drug immune responses are a unique risk factor for biotherapeutics, and undesired immunogenicity can alter pharmacokinetics, compromise drug efficacy, and in some cases even threaten patient safety. To fully capitalize on the promise of biotherapeutics, more efficient and generally applicable protein deimmunization tools are needed. Mutagenic deletion of a protein’s T cell epitopes is one powerful strategy to engineer immunotolerance, but deimmunizing mutations must maintain protein structure and function. Here, EpiSweep, a structure-based protein design and deimmunization algorithm, has been used to produce a panel of seven beta-lactamase drug candidates having 27–47% reductions in predicted epitope content. Despite bearing eight mutations each, all seven engineered enzymes maintained good stability and activity. At the same time, the variants exhibited dramatically reduced interaction with human class II major histocompatibility complex proteins, key regulators of anti-drug immune responses. When compared to 8-mutation designs generated with a sequence-based deimmunization algorithm, the structure-based designs retained greater thermostability and possessed fewer high affinity epitopes, the dominant drivers of anti-biotherapeutic immune responses. These experimental results validate the first structure-based deimmunization algorithm capable of mapping optimal biotherapeutic design space. By designing optimal mutations that reduce immunogenic potential while imparting favorable intramolecular interactions, broadly distributed epitopes may be simultaneously targeted using high mutational loads.

Keywords: Deimmunization, T cell epitope deletion, Immunogenicity, Computational protein design, Biotherapeutics

Introduction

Biotherapeutics are an increasingly important segment of the pharmaceuticals market (Aggarwal 2014), but relative to their potential, these powerful drugs are still underdeveloped and underutilized in part due to unique risk factors, such as the potential to induce anti-drug immune responses (Baker et al. 2010; Barbosa 2011). Immunogenicity causes a range of undesirable complications including altered pharmacokinetics, loss of efficacy, allergic reactions, immune complex toxicity, and in rare cases even more serious adverse events (De Groot and Scott 2007; Schellekens 2010).

Anti-protein immune responses are complex in nature and stem from an array of contributing factors. For example, glycosylation and other post-translational modifications can strongly influence immunogenicity (Schellekens 2002), and immune responses to autologous human proteins may in some cases involve undermining regulatory T cell tolerance mechanisms (De Groot and Scott 2007). One common driver of anti-drug immune responses is recognition of immunogenic peptide epitopes by antigen presenting cells (APCs) (Schellekens 2002). After a protein is internalized by APCs, it is processed into small peptide fragments, some of which are loaded into the groove of class II major histocompatibility complex proteins (MHC II, or HLA in humans). At the APC surface, peptide-MHC II complexes are queried by cognate surface receptors on CD4+ helper T cells, and true immunogenic peptides, termed T cell epitopes, result in the formation of ternary MHC II-peptide-T cell receptor complexes(Trombetta and Mellman 2005). This critical molecular recognition event induces a signaling cascade that drives helper T cell stimulation, B cell maturation, and production of IgG antibodies that specifically bind the immunogenic protein.

Detailed knowledge of the cellular and molecular events underlying anti-protein immune responses has resulted in strategies for biotherapeutic deimmunization. Namely, immunogenic T cell epitopes may be deleted through mutagenesis of residues that drive peptide-MHC II association. Initially, T cell epitope deletion was accomplished by large scale experimental efforts that tested the immunogenic potential of every possible peptide epitope, attempted to deimmunize confirmed peptide epitopes by alanine-scanning or similar trial and error mutagenesis, incorporated the subset of validated deimmunizing mutations back into the full length protein, and then assessed whether or not the variants were stable, active, and less immunogenic (Collen et al. 1996; Harding et al. 2005; Yeung et al. 2004). These experimentally driven approaches continue to be leveraged to great effect (Cizeau et al. 2009; Harding et al. 2010; Mazor et al. 2012), but increasingly epitope identification and deletion is facilitated by immunoinformatics tools (Bryson et al. 2010; Cantor et al. 2011; De Groot and Scott 2007; Moise et al. 2007).

Building upon available tools, we have developed deimmunization algorithms that integrate epitope prediction with computational analysis of the functional consequences likely associated with prospective deimmunizing mutations (Parker et al. 2011; Parker et al. 2010). These integrated protein design tools are able to simultaneously optimize proteins for both low immunogenic potential and high level molecular function, potentially enhancing and accelerating biotherapeutic deimmunization. Indeed, model studies with the P99 beta-lactamase enzyme (P99βL) have shown that these tools efficiently select mutations that disrupt peptide-MHC II binding while preserving activity and stability (Osipovitch et al. 2012; Salvat et al. 2014b). More recent algorithms have incorporated explicit molecular modeling to enable structure-based design of immunotolerant protein therapies (Choi Y et al. ; Parker et al. 2013), and application of one such method to GFP and Pseudomonas exotoxin provided experimental confirmation that stimulatory epitopes had been suppressed (King et al. 2014). Thus, structure-based deimmunization tools hold great promise for improving biotherapeutic design and development.

Here, we have applied the structure-based EpiSweep deimmunization algorithm (Parker et al. 2013) to P99βL, using a Pareto optimal design strategy to assess the tradeoffs between deimmunizing efficiency and maintenance of function at a high mutational load. Seven 8-mutation designs have been constructed, and their catalytic activity, thermostability, and reactivity with human MHC II immune proteins have been quantified. The results show that structure-based design enables efficient deletion of broadly distributed epitopes under high mutational loads, and comparison to earlier sequence-based deimmunization of P99βL (Salvat et al. 2015) has provided new insights into the respective advantages of both methodologies.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technology (San Diego, CA). All restriction enzymes and PCR reagents were purchased from New England BioLabs (Ipswich, MA). Growth medium was purchased from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Plasmid purification kits and Ni-NTA resin were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). DNA purification kits were from Zymo Research (Irvine, CA). Nitrocefin was purchased from Oxoid (Cambridge, UK). Cephalexin was purchased from MP Biomedical (Santa Ana, CA). Human lysozyme and SYPRO Orange were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Peptides were ordered from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ), and were greater than 85% pure. Biotinylated tracer peptides were purchased from 21st Century Biochemicals (Marlborough, MA). MHC II DR molecules were from Benaroya Research Institute (Seattle, WA). Anti-MHC II-DR antibody from Biolegend (San Diego, CA), and DELFIA Eu-labeled Streptavidin was from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). Unless noted, all other chemicals and reagents were from VWR (Radnor, PA).

Computational Deimmunization

The EpiSweep algorithm (Parker et al. 2013) was employed to design deimmunized P99βL variants. EpiSweep was implemented and applied as detailed by Parker et al. (2013); a summary of the approach follows. EpiSweep takes as input the wild type amino acid sequence and corresponding structure (either experimentally determined or a high-quality model), a position-specific list of allowed mutations, a desired overall mutational load, and position-specific scoring matrices to assess the impacts of mutations on immunogenicity and structural energy. Since immunogenicity and energy are incommensurate and in fact competing criteria, EpiSweep optimizes variants making the best trade-offs, termed “Pareto optimal”. The Pareto optimal variants are undominated, in that no other variant is simultaneously better for both criteria. To identify the Pareto optimal variants, EpiSweep starts with the wild type, which has low energy but high immunogenicity, and “sweeps” across the immunogenicity score to successively more deimmunized variants, reducing immunogenicity at an increasing energetic penalty. At each step of the sweep (i.e., target immunogenicity score), it identifies the variant that has the lowest energy score for that immunogenicity score (at the desired mutational load).

The EpiSweep parameters were instantiated for P99βL as follows:

Immunogenicity

Predicted T cell epitope content was assessed against the four common MHC II alleles DRB1*0101, 0401, 0701, and 1501. The ProPred epitope predictor (Singh and Raghava 2001) was applied at a 5% threshold separately for each allele. The epitope score for a protein (Sepi) was defined as the total number of constituent nonamer peptides predicted to bind human MHC II, treating each allele separately such that promiscuous binders would be emphasized. A more in depth discussion of Sepi calculation and optimization is provided elsewhere (Parker et al. 2013).

Allowed Mutations

Sequences of Beta-latamase family Pfam 00144 were collected (Bateman et al. 2004). Sequences were filtered to eliminate those with >25% gaps, <35% identity to wild type, and >90% identity to wild-type or each other. Allowed mutations were defined as previously described (Salvat et al. 2015): excluding mutations to/from Pro and Cys, those amino acids that appeared in the multiple sequence alignment at least as frequently as expected according to a background distribution (Mccaldon and Argos 1988) and deleted at least one predicted epitope without introducing novel epitopes.

Structural Energy

Deimmunized designs were optimized to be energetically favorable in the context of the structural backbone from the PDB file 1XX2 (chain A). Using a previously described rotamer library (Lovell et al. 2000), a position-specific energy matrix was built for the wild type amino acids and allowed mutations. Single and pairwise rotamer energy values were calculated using the open source OSPREY software (ver 2.0) (Chen et al. 2009; Gainza et al. 2012), according to the AMBER force field (Pearlman et al. 1995) and residue reference energies for protein redesign (Lippow and Tidor 2007). The structure-based energy score (Sstr) of the lowest-energy rotameric conformation for a variant was calculated as the sum of the relevant single and pairwise energy terms in the matrix.

Protein Design

EpiSweep identified all Pareto optimal 8-mutation variants in the Sepi vs. Sstr design space, performing an optimization sweep from more to less immunogenic and more to less stable. Subsequently, additional iterations produced near-optimal sweeps, yielding a total of 20 sets of designs.

Energy Minimization

All-atom models were subsequently developed for the designs by incorporating the selected rotamers onto the original structure. The resulting models were energy minimized using TINKER (Ponder 2011), according to the AMBER-f99sb force field parameters (Hornak et al. 2006) and the generalized Born model with solvent accessible surface area (GBSA) (Still et al. 1990). For later use in selecting variants for experimental evaluation, each design was annotated with the resulting minimized energy ( ), and the root-mean squared deviation (RMSD) between the original and energy-minimized structures.

Cloning, Expression, and Purification

Engineered enzymes were cloned, expressed, and purified as previously described (Osipovitch et al. 2012). All protein preparations were >95% pure, and yields were 1–30 mg/liter of cell culture, depending on the enzyme variant.

Activity Analysis

Michaelis-Menten kinetics were assessed using previously described methods (Salvat et al. 2014b). Briefly, a colorometric assay was performed in 96-well plates using 10 μM to 500 μM of nitrocefin. Initial reaction rates were plotted versus substrate concentration, and kinetic parameters were determined by non-linear regression (Graphpad Prism v4.0). Measurements were made in triplicate, and enzymes were purified and assayed in biological duplicate. Significant deviations from previous studies (Salvat et al. 2015; Salvat et al. 2014b) were observed due to lot to lot variability in the nitrocefin substrate (Table S1), and comparisons to earlier work therefore used values normalized to the wild type values from the cognate studies.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were determined with cephalexin by growing a BL21(DE3) host bearing the empty pET26b vector at 37°C in LB medium containing 30 μg/mL kanamycin and 20 ng/mL of each purified P99βL variant. Cephalexin was serially diluted 1:2 from an initial concentration of 750 μg/mL, and MIC were reported as the lowest concentration of cephalexin that prevented visible outgrowth at 20 hours.

Thermostability Analysis

Differential scanning fluorimetry was performed as previously described (Niesen). Breifly, proteins were diluted in PBS to a concentration of 100 μg/ml, and SYPRO Orange dye was added to a final concentration of 5×. Samples were exposed to a temperature gradient from 25–94°C with a 1 minute equilibration at each degree centigrade. Fluorescence was quantified in an Applied Biosystems ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR machine.

MHC Binding Assays

MHC-II competition binding assays were performed using a 384-well high throughput assay as described in detail elsewhere (Salvat et al. 2014a). Binding assays were performed for the four alleles: DRB1*0101, 0401, 0701 and 1501, which provide broad representation of class II MHC binding pockets (Southwood et al. 1998). The data were fit to the one-site log(IC50) model by non-linear regression in GraphPad Prism v.5 software.

The overall immunoreactivity of each protein variant was calculated using equation 1, as previously described (Salvat et al. 2015):

| (1) |

where “ ” is the mean IC50 value averaged over all component peptides having affinities <250 μM, “#Nonbinders” is the total count of component peptides with affinities ≥250 μM, and the subscripts “mut” and “wt” indicate mutant and wild type proteins, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Linear regressions of experimental data vs. predictions employed an F test for statistical significance of non-zero slopes. Significance was determined at the α=0.05 level.

Results and Discussion

Epitope Prediction

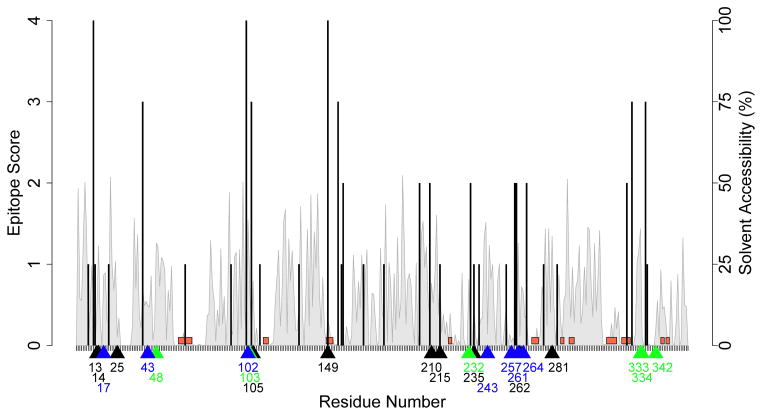

Wild type P99βL was analyzed with the ProPred epitope predictor (Singh and Raghava 2001) set to a 5% threshold. It bears noting that there are numerous publically available epitope predictors (Nielsen et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2008), but we used here ProPred so as to enable direct comparison with previous P99βL deimmunization efforts that employed sequence-based design (Salvat et al. 2015). For the same reason, only alleles DRB1*0101, 0401, 0701, and 1501 were analyzed, and as a result, existing and neoepitopes for other alleles were not considered here. Putative T cell epitopes were broadly distributed throughout the sequence, and were associated with residues on the protein surface, in the protein interior, and both proximal and distal to active site residues (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Epitope map of P99βL.

The P99βL sequence was analyzed using ProPred set to a 5% threshold for the alleles DRB1*0101, 0401, 0701, and 1501. The epitope score, or number of alleles that bind each nonamer peptide (left y-axis), is indicated by a black bar at the starting position of the peptide (x-axis). The solvent accessibility (right y-axis) is indicated by the grey trace. Positions within 7Å of the active site (based on Cβ, with Cα for Gly) are bracketed in red along the x-axis. Locations of mutations in the seven structure-based designs are indicated by blue arrows, those in previous sequence-based designs are indicated by green arrows, and those common to both studies are indicated with black arrows.

Computational Design

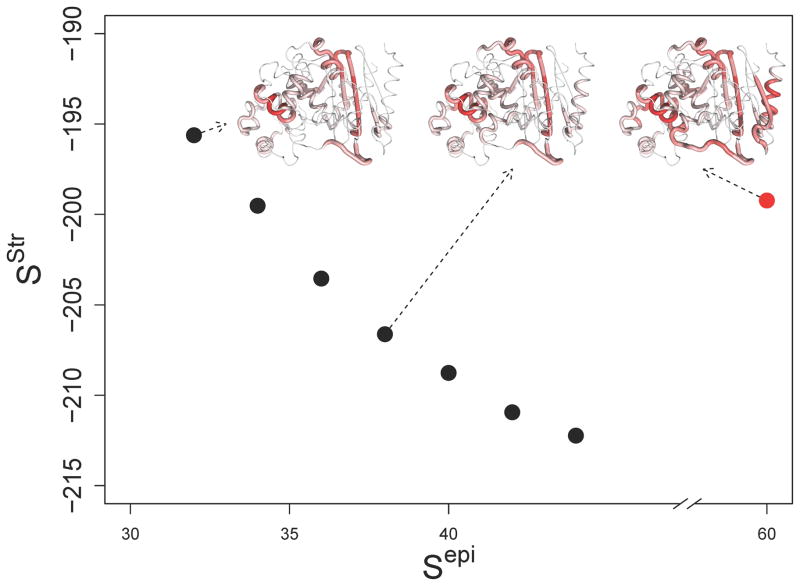

The two objectives of low immunogenic potential and high molecular function are competing in nature, and intuition suggests that there is no single global optimum with respect to protein deimmunization. Instead, there exist tradeoffs between reduced epitope content and molecular fitness, and the protein design space is bounded by a “Pareto” frontier of variants, i.e. undominated proteins for which no other single design exhibits better performance in both criteria (He et al. 2012). Previously, a sequence-based deimmunization algorithm was employed to design 18 Pareto optimal P99βL variants having from one to eight mutations each (Salvat et al. 2015). Here, structure-based EpiSweep was used to optimize tradeoffs between P99βL epitope score (Sepi) and energy score (Sstr) specifically at high mutational loads (eight per protein). A total of 368 deimmunized designs were generated and subjected to all atom energy minimization. A final set of seven variants (one each at Sepi =32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, and 44) were selected based on a rank sum of Sstr (energy score prior to minimization), minimized energy score ( ), and post-minimization RMSD values against the wild type backbone (Table S2, structure-based designs named by epitope score, e.g. ‘Str 32’). These variants, while having a constant mutational load, span a large range of Sepi scores by virtue of their increasingly aggressive deimmunizing mutations (i.e., substitutions that delete more predicted epitopes). As a result, their respective Sstr energy scores suggest the series should experience a progressive loss of stability and/or activity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pareto frontier of the P99βL design space.

The computed Sstr is plotted vs. the computed Sepi for each of the seven unique designs (indicated as blue circles, wild type in red). Sstr, the rigid energy score, is one component of the structure-based design process. Sepi is the total predicted epitope count for each protein. The epitope content of three representative proteins (Str 32, Str 38, and wild-type) is shown mapped onto the P99βL structure (PDB ID 1XX2A). Epitope density is represented with a color gradient, where red indicates dense overlapping epitopes and white indicates sequences free of putative epitopes.

Thermostability Analysis

All seven P99βL variants expressed well and were easily purified. The stability of each purified enzyme was quantified by determining melting temperatures (Tm) via differential scanning fluorimetry (Nielsen et al. 2007) (Table 1). Despite their high mutational load, the structure-based designs generally maintained good stability, with Tm values ranging from 48.83–53.60°C (wild-type Tm =56.10 °C). None of the enzymes exhibited significant unfolding at 37°C, the temperature of direct physiological significance (data not shown).

Table 1.

Design composition and performance parameters

| Design ID | A13 | N14 | T17 | V25 | F43 | Q102 | R105 | L149 | R210 | M215 | M235 | V243 | S257 | R261 | I262 | S264 | N281 | Sepi | SStr | SAES | k cat (s−1) |

Km (μM) |

kcat/Km (s−1μM−1) |

MIC (μM) |

Tm (°C) |

Global Imm.a (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 60 | −199 | −10939 | 360 ± 20 | 80 ± 10 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 437.5 ± 62.5 | 56.07 ± 0.02 | 100 | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Str 44 | R | Q | I | D | H | L | Q | K | 44 | −212 | −10692 | 440 ± 30 | 100 ± 10 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 562.5 ± 83.9 | 53.6 ± 0.03 | 53 | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Str 42 | R | Q | D | Q | H | Q | Q | K | 42 | −211 | −10817 | 260 ± 20 | 64 ± 9 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 312.5 ± 39.5 | 50.34 ± 0.02 | 64 | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Str 40 | R | Q | W | D | Q | H | E | K | 40 | −209 | −10926 | 280 ± 10 | 73 ± 7 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 218.8 ± 31.3 | 53.28 ± 0.01 | 61 | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Str 38 | R | Q | W | D | Q | H | A | K | 38 | −207 | −10862 | 166 ± 6 | 49 ± 4 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 187.5 ± 0 | 52.93 ± 0.02 | 56 | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Str 36 | R | Q | W | D | K | Q | H | A | 36 | −204 | −10747 | 170 ± 10 | 50 ± 10 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 93.8 ± 0 | 49.74 ± 0.54 | 55 | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Str 34 | D | W | D | Q | H | Q | A | K | 34 | −200 | −10839 | 175 ± 5 | 54 ± 3 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 140.6 ± 21 | 53.13 ± 0.02 | 38 | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Str 32 | D | W | D | K | Q | Q | L | A | 32 | −196 | −10936 | 148 ± 5 | 40 ± 3 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 93.8 ± 0 | 48.83 ± 0.02 | 38 | |||||||||

Global Immunoreactivity (see equation 1)

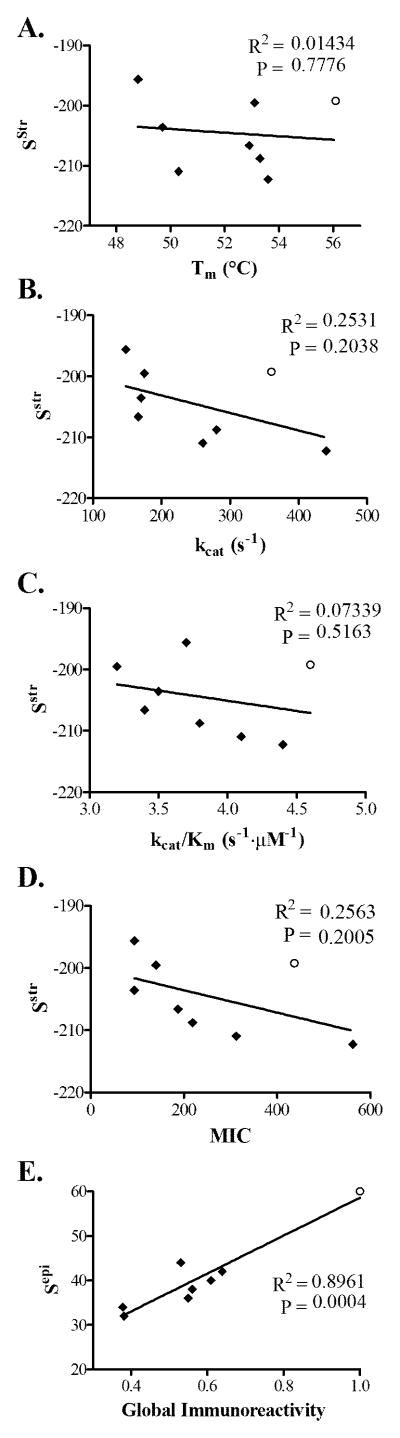

Notably, designs bearing the R105K mutation (Str 36 and Str 32) exhibited Tm values ~3 °C lower than most other designs. Previous work with a sequence-based algorithm made extensive use of the R105S deimmunizing mutation, and associated variants were found to have a similarly significant reduction in thermostability (averaging −7 °C across 13 designs, (Salvat et al. 2015)). In targeting the epitope dense peptide spanning residues 98–113 (Figure S1), EpiSweep made the more conservative R105K substitution, but nonetheless the two cognate Str variants experienced marked destabilization (−6.33 and −7.24 °C, respectively). As a whole, however, Episweep tended to avoid R105 mutations (used in only 2 of 7 designs), whereas the earlier sequence-based method favored the R105S substitution (used in 6 of 7 designs). Among the small set of seven designs from the current study, there was no significant correlation between Sstr energy scores and Tm values (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Correlations between computational design parameters and experimentally measured performance metrics.

A Sstr vs. Tm.

B Sstr vs. kcat.

C Sstr vs. kcat /Km.

D Sstr vs. MIC.

E Sepi vs. Gobal Immunoreactivity

Pareto optimal enzymes are shown as solid black diamonds and wild type P99βL is shown as an open black circle. Linear regressions are shown along with R2 values, and an F test was used to determine statistical significance for non-zero slopes (P values are provided).

Activity Analysis

The mutational effects on catalytic performance were assessed from Michaelis-Menten kinetic analysis with the colorimetric substrate nitrocefin (Table 1). All designs retained impressive activity, exhibiting a minimum of 40% wild type maximum reaction velocity (kcat, Str 32) and 70% wild type catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km, Str 34). The two point mutations L149Q and I262A were responsible for the most significant reductions in activity, where the former represents an element of the P99βL active site (Figure 1). Str 44, the single design lacking both L149Q and I262A, had 120% wild type kcat and 95% wild type kcat/Km. Str 42 and 40, which bear L149Q but not I262A, had 72% and 78% wild type kcat and 89% and 83% wild type kcat/Km, respectively. In contrast, the remaining four designs incorporated both mutations and manifested greater losses in catalytic performance, retaining on average 46% wild type kcat and 75% wild type kcat/Km. The high incorporation frequency of these mutations was due to their predicted deimmunizing efficiency (Figure S1), which was ultimately born out in practice (see below).

In addition to kinetics, the enzymes’ activities were also assessed using a modified minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay with the antibiotic cephalexin. In this case, E. coli cells lacking an endogenous beta-lactamase antibiotic resistance marker were grown in medium containing serial dilutions of cephalexin and 20 ng/ml of purified P99βL variants. Higher levels of enzyme functionality facilitate outgrowth at higher concentrations of cephalexin. The MICs of EpiSweep designs ranged from 20% to 130% that of wild type P99βL (Table 1), and the values generally tracked with the Michaelis-Menten parameters. Not surprising, therefore, MIC values clearly partition with the L149Q and I262A substitutions. Interestingly, Str 32 and Str 36 exhibited the least favorable MIC values, and these were the only two designs encoding the structurally destabilizing R105K mutation. Thus, while none of the EpiSweep designs exhibited significant unfolding at 37 ºC in the differential scanning fluorimetry assay, the substantial Tm reduction caused by R105K appears to impact performance under conditions of the MIC assay.

Similar thermostability, various measures of activity showed no significant correlations with predicted Sstr energy values (Figure 3B–D). As a whole, however, there was an overall trend towards progressive loss of performance with increasingly aggressive deimmunized designs.

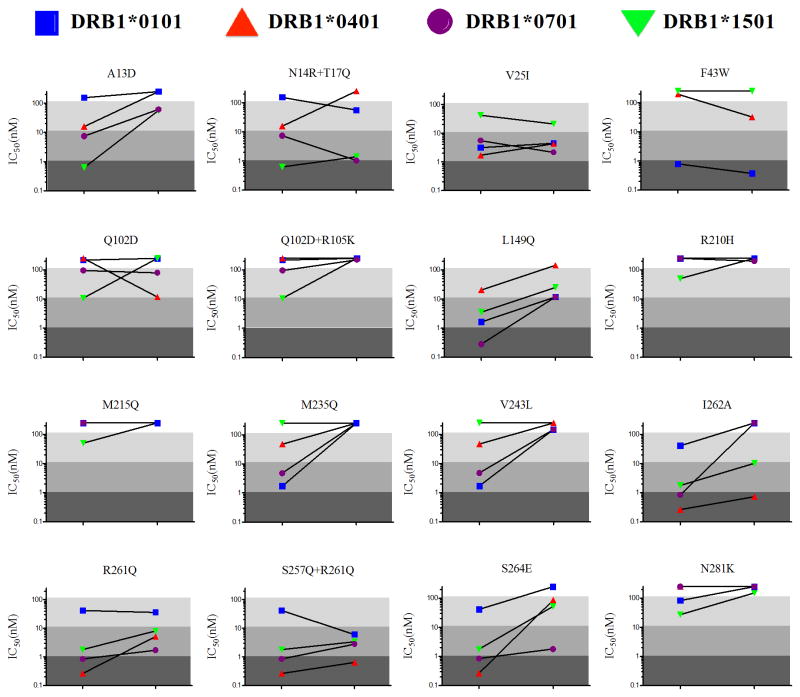

Immunoreactivity by Peptide-MHC II Binding

The immunoreactivity of putative P99βL peptide epitopes was quantified using competition binding assays with recombinant human MHC II molecules (Salvat et al. 2014a). Synthetic peptide fragments of wild type P99βL were designed so as to encompass each of the epitopes targeted by the EpiSweep deimmunization algorithm, and corresponding variant peptides were synthesized to represent the deimmunized designs. Peptide affinities are reported as IC50 values, and putative epitopes were classified as strong (IC50<1 μM), moderate (1 μM≤IC50<10 μM), weak (10 μM≤IC50<100 μM), or non-binders (IC50≥100 μM) (Table 2). These assays are a well-established metric for immunogenic potential (Moise et al. 2012; Osipovitch et al. 2012; Salvat et al. 2014a; Steere et al. 2006; Sturniolo et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2008), and a growing body of experience has led to consensus guidelines regarding appropriate thresholds peptide-MHC II ‘binding’ (Paul et al. 2013).

Table 2.

Peptide-MHC II Binding Affinities and Correlation with Predictions*

| Name | # Predicted Epitopes | Experimental IC50 (μM) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0101 | 0401 | 0701 | 1501 | 0101 | 0401 | 0701 | 1501 | |

| A13+N14+T17 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 156 | 15.95 | 0.62 | 7.40 |

| A13D | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | >250 | >250 | 56.1 | 61.3 |

| N14R+T17Q | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 56 | >250 | 1.41 | 1.05 |

| V25 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3.15 | 1.70 | 42.91 | 5.61 |

| V25I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.46 | 4.29 | 21.3 | 2.16 |

| F43 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.79 | 199 | >250 | >250 |

| F43W | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.38 | 32.6 | >250 | >250 |

| Q102+R105 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 220 | >250 | 10.7 | 96.3 |

| Q102D | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | >250 | 11.8 | >250 | 80.4 |

| Q102D+R105K | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | >250 | >250 | >250 | 223 |

| L149 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.64 | 20.6 | 3.54 | 0.28 |

| L149Q | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.8 | 146 | 25.1 | 11.8 |

| R210+M215 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | >250 | >250 | 51.1 | >250 |

| R210H | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | >250 | >250 | >250 | 201 |

| M215Q | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | >250 | >250 | >250 | >250 |

| M235+V243 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.71 | 48 | >250 | 4.79 |

| M235Q | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | >250 | >250 | >250 | >250 |

| V243L | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 149 | >250 | >250 | 149 |

| S257+R261+I262+S264 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 41.8 | 0.26 | 1.79 | 0.85 |

| S257Q+R261Q | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6.08 | 0.64 | 3.41 | 2.83 |

| R261Q | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 35.8 | 5.12 | 8.08 | 1.72 |

| I262A | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | >250 | 0.73 | 10.3 | >250 |

| S264E | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | >250 | 86.5 | 52.9 | 1.8 |

| N281 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 85 | >250 | 27.4 | >250 |

| N281K | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | >250 | >250 | 151 | >250 |

| Accuracy (62% overall) | 52% | 76% | 60% | 60% | ||||

| Sensitivity (55% overall) | 50% | 75% | 53% | 43% | ||||

| Precision (67% overall) | 50% | 75% | 73% | 75% | ||||

| Specificity (70% overall) | 54% | 77% | 70% | 82% | ||||

The number of predicted epitopes within a given synthetic peptide are shown on the left for each MHC allele, with correct predictions based on an experimental binding cutoff ≤100 μM highlighted in grey. The measured IC50 values are shown on the right, and peptides are categorized as strong (IC50<1 μM, red), moderate (1 μM≤IC50<10 μM, orange), weak (10 μM≤IC50<100 μM, yellow), or non-binding (IC50 ≥100 μM, white). Accuracy, sensitivity, precision, and specificity are provided as percentages (bottom left).

High affinity interaction between peptide antigens and class II MHC is a key determinant of subsequent T cell immunogenicity (Hill et al. 2003; Sidney et al. 2002; Southwood et al. 1998; Weaver and Sant 2009), although it bears noting that rare examples of low affinity yet T cell stimulatory peptides are known (Muraro et al. 1997; Southwood et al. 1998). Four out of nine wild type P99βL peptides were found to possess sub-micromolar IC50’s for one or more of the tested alleles. The wild type peptide ‘A13+N14+T17’ was a high affinity binder of DRB1*0701 (IC50=620 nM), but the A13D mutation converted the peptide to a weak binder and N14R+T17Q converted it a moderate binder (Figure 4). Wild type peptide L149 is especially immunoreactive, binding allele 1501 with sub-micromolar affinity and alleles 0101 and 0701 with single digit micromolar IC50’s. The L149Q mutation reduced 1501 affinity by 40-fold, and reduced binding to 0101, 0401, and 0701 by 7-fold each. Wild type peptide S257+R261+I262+S264 also bound all four alleles, and it possessed sub-micromolar affinity for both 0401 and 1501. EpiSweep targeted this immunogenic region with four different designs, each of which was generally successful in reducing overall peptide immunoreactivity (Figure 4). The I262A and S264E designs were perhaps the most effective, with the former ablating binding to allele 1501 and the latter reducing 0401 binding by 330-fold. The F43 wild type peptide was the fourth high risk binder, having IC50=0.79 nM for allele 0101. Similar to previous sequence-based designs, which unsuccessfully employed the I48V mutation (Salvat et al. 2015), the EpiSweep designed F43W mutation failed to effectively deimmunize this putative epitope.

Figure 4.

Peptide binding affinities for human MHC II proteins.

The peptide-MHC II binding affinities are represented as IC50 values and are plotted for each pair of wild-type and variant peptides. Shading indicates binding strength by category: strong (IC50<1 μM, dark grey), moderate (1 μM≤IC50<10 μM, medium grey), weak (10 μM≤IC50<100 μM, light grey), or non-binding (IC50 ≥100 μM, white). The slope of the connecting lines are a relative measure of deimmunizing efficacy, where larger positive slopes indicate a greater fold decrease in affinity relative to wild type, and negative slopes indicate a mutation that enhanced binding.

A total of 25 peptides, 9 wild type and 16 engineered, were analyzed with four human MHC II proteins to produce 100 IC50 affinity measurements. Of the 64 pairs of wild type and cognate deimmunized affinities (Figure 4), there were 23 cases in which the designed mutation either ablated binding or reduced MHC II affinity by more than 10-fold. There were an additional 10 instances wherein the designed mutation reduced affinity by 5- to 10-fold. In contrast, there were only four instances in which binding was increased by more than 5-fold, only one of which was a 10-fold+ difference (Q102D for allele 0401). In two of the four cases of substantially enhanced binding, peptide-MHC II interactions were in fact predicted (Q102D with allele 0401, and S257Q+R261Q with allele 0101; Figure S1). Thus, as a whole the EpiSweep algorithm selected mutations and combinations of mutations that effectively suppressed immunoreactivty.

To correlate the experimentally measured MHC II affinities with the algorithm’s binary prediction of epitopes (i.e. those in the top 5% of predicted scores), we compared predictions to all peptide binders having a threshold IC50≤100 μM, a metric we have used in other P99βL studies (Osipovitch et al. 2012; Salvat et al. 2015; Salvat et al. 2014b). Given this experimental threshold and ProPred prediction cutoff, the protein design process had an overall accuracy of 62%, a sensitivity of 55%, a specificity of 70% and a precision of 67% (Table 2), similar to what has been observed with previous sequence-based deimmunization efforts (Osipovitch et al. 2012; Salvat et al. 2015; Salvat et al. 2014b).

To assess immunoreactivity at the whole protein level, we developed a global immunoreactivity score (see equation 1). This measure incorporates the quantified IC50 value for each protein’s component peptides combined with a multiplier for the number of component peptides for which binding was too weak to measure accurately. The global immunoreactivity values ranges from 38%–63% that of wild type P99βL. Designs Str 36 through Str 44 exhibit approximately half the immunoreactivity of wild type, whereas designs Str 32 and Str 34, which incorporate the A13D mutation, are both substantially less immunoreactive (38% wild type each). A comparison of global experimental immunoreactivity with the Sepi design parameter revealed a highly significant correlation (Figure 3E), as was seen in earlier studies using a sequence-based design method (Salvat et al. 2015). Overall, the ProPred component of EpiSweep proved to be highly predictive of MHC II reactivity.

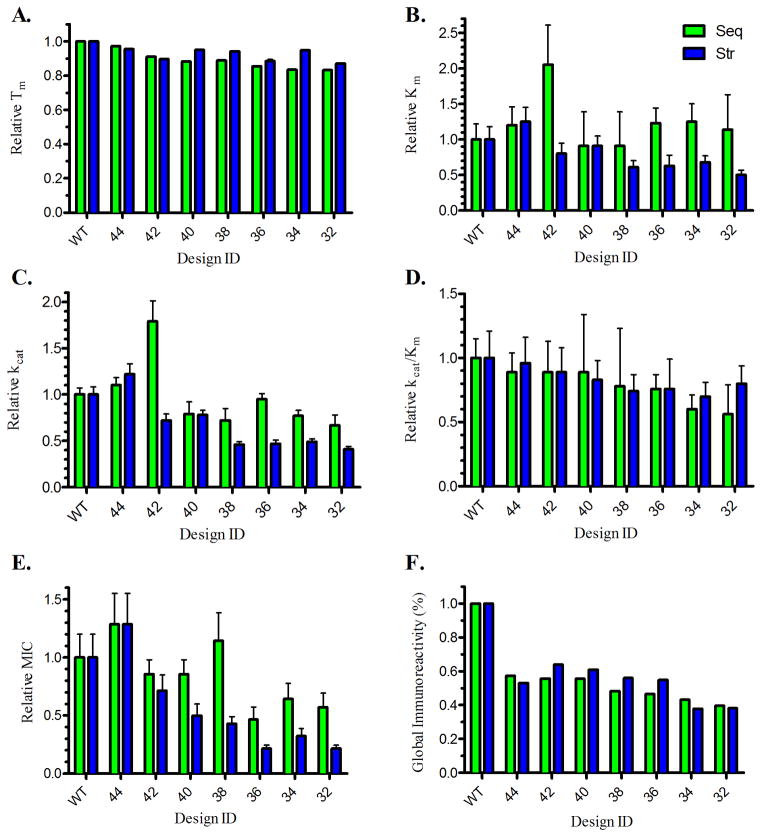

Comparison to Sequence-based Designs

As noted above, one goal of the current structure-based studies was generating a matched data set that would facilitate direct head-to-head comparison with previous sequence-based Pareto optimal deimmunization of P99βL (Salvat et al. 2015). Both the current structure-based algorithm and the prior sequence-based algorithm preselect allowed mutations based on information from the evolutionary sequence record (using the same criteria for this comparative study), and then optimize combinations of these mutations that are predicted to yield deimmunized yet functional variants. They differ in how they assess the impact of deimmunizing mutations on function: EpiSweep models molecular energies whereas the earlier method evaluates a one- and two-body statistical sequence potential derived from the multiple sequence alignment of homologs. To make the most direct possible comparison between the use of molecular energies and the statistical sequence potential, we constrained the pairwise comparisons such that mutational load and predicted epitope scores were explicitly matched; i.e., the two methods generated the best possible variants, according to their respective scores, for the given number of mutations and corresponding epitope scores. To match the EpiSweep designs, we selected seven sequence-based designs that bore eight mutations each and had Sepi scores of 32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, and 44 (variants named ‘Seq 32’, ‘Seq 34’, etc.). The comparison was therefore made on proteins that exhibited matched design parameters, considering experimentally determined performance measures as the outcome variables of interest.

The amino acid compositions of the Str versus Seq designs are entirely unique; the two deimmunization algorithms did not generate any common 8-mutation designs at the specified Sepi scores, and L149Q, R210H, and N281K were the only mutations that appeared at least twice in both sets of protein plans (Table S3). While the two algorithms selected divergent amino acid substitutions, both targeted nearly identical epitopes in the N-terminal half of the enzyme (Figure 1). In contrast, beyond the epitope cluster centered on residue M235, the Str and Seq designs mostly targeted distinct immunogenic regions. Five of the eight Seq designs concentrated on the epitope dense region from Y325 to P345 (Figure 1, green arrows), whereas the Str designs uniquely targeted the overlapping cluster from L254 to G268 (Figure 1, blue arrows).

The molecular performance of each variant pair was compared (Figure 5). Note that we have observed significant differences in Michaelis-Menten kinetic results due to lot to lot variability in the nitrocefin substrate (Table S1), and therefore Seq versus Str comparisons were done on a relative basis, normalizing to the wild type results from the corresponding study. While both design methods generally maintained good thermostability, the Str variants had a higher Tm in 5/7 cases. In contrast, the Seq designs retained higher maximum reaction velocities in 6/7 instances, though in 5/7 cases Str designs won out with respect to catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km). The Seq designs manifested uniformly higher MIC values (7/7 comparisons). The observation that Seq designs generally possessed higher relative activity was most likely due to their low frequency of mutations at L149 and I262 (Table S3).

Figure 5.

Comparison of sequence-based and structure-based designs

A Relative Tm.

B Relative Km.

C Relative kcat.

D Relative kcat /Km.

E Relative MIC.

F Gobal Immunoreactivity

Relative parameters, normalized to wild type from the respective study, are provided for seven sequence-based designs (green) and seven structure-based designs (blue).

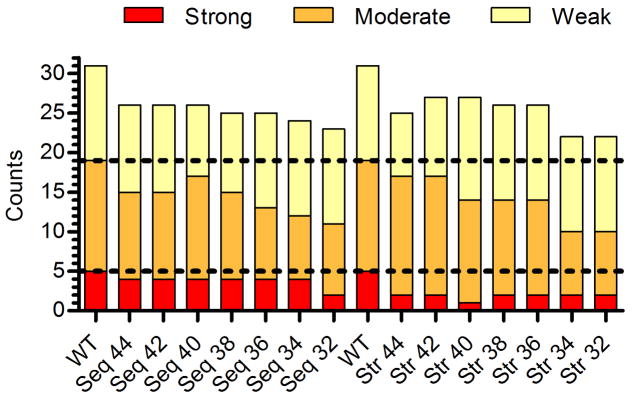

The peptide-MHC II binding potential of Str and Seq design pairs was compared using both qualitative and quantitative metrics. The quantitative global immunoreactivity of both design sets were generally similar, with Seq designs winning out by small degrees in 4/7 cases and Str designs by comparably small margins in 3/7 cases (Figure 5F). Importantly, confirmed T cell epitopes have MHC II binding affinities in or below the low micromolar IC50 range. Therefore, we also compared the Seq and Str immunoreactivity using our previously defined categorical thresholds, where strong and moderate binders represent the most serious risk. The wild type enzyme had a total of 36 measured interactions: five strong, fourteen moderate, twelve weak, and thirteen non-binding (Figure 6). Structure-based EpiSweep removed a substantial number of high affinity binders, deleting an average of 3.14 strong binders per protein compared to just 1.3 deletions in the Seq designs (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P=0.006). The two design methods disrupted moderate binding peptides with similar efficiencies, where Seq designs deleted an average of 3.7 compared to 2.1 for the Str designs (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P=0.25). Overall, both methods of deimmunization yielded an average of 19/36 non-binding peptides, compared to only 13/36 for wild type P99βL.

Figure 6.

Comparison of whole-protein categorical immunoreactivity for sequence- and structure-based designs. The counts for constituent peptides from each enzyme were summed and plotted by semi-quantitative category (y-axis). Each individual peptide’s binding strength for the four MHC II alleles DRB1*0101, 0401, 0701, and 1501 were binned as strong (IC50<1 μM, red), moderate (1 μM≤IC50<10 μM, orange), weak (10 μM≤IC50<100 μM, yellow), or non-binding (IC50 ≥100 μM, not shown). The horizontal hatched lines are visual guides for the wild type binding counts in each category.

By categorical analysis, EpiSweep generated designs with lower overall MHC II binding potential. Because both methods employed the ProPred epitope predictor, differences between the sequence-based and structure-based designs are due to differences in their respective assessment of ‘optimal’ deimmunizing mutations, as judged by the likelihood that a substitution will preserve enzyme stability and activity. Considering only the results presented here, statistical analysis of sequence conservation trends towards better maintenance of activity (Figure 5C and E). As a corollary, the Seq designs largely avoided mutations at L149 and I262 (Table S3), which proved to be detrimental from a functional perspective (Table 1). However, L149Q and I262A were, at the same time, two of the most effective substitutions with respect to disrupting molecular recognition by human MHC II (Figure 4 and Table 2). Thus, as a tradeoff to accepting these partially deactivating mutations, the structure-based EpiSweep designs benefited from lower overall immunoreactivity.

Conclusion

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of structure-based deimmunization tools is their potential to facilitate deimmunization of difficult protein targets having many distributed epitopes. In any such situation, conventional trial and error experimental methodologies, while proven successful (Mazor et al. 2014), tend to be excessively laborious and expensive. Here, we describe experimental validation of a structure-based deimmunization algorithm able to assess tradeoffs between a protein’s immunogenic potential and its molecular function. Among seven 8-mutation P99βL designs, MHC II binding potential was reduced to as little as 38% wild type (Table 1). Importantly, the number of high risk, sub-micromolar binding peptides was reduced by up to 80% (Figure 6, design Str 40). While it bears noting that lower affinity peptides can elicit clinically relevant immune responses (Muraro et al. 1997), systematic analysis of DR restricted protein immunogenicity has shown that high affinity MHC II binding correlates with T cell activation (Hill et al. 2003; Southwood et al. 1998; Weaver and Sant 2009), and the methods described here should therefore have practical utility in derisking immunogenic proteins. Fully assessing the success of the current deimmunization effort would require more advanced immunological assays with human peripheral blood cells, humanized mouse models, and ultimately human subjects. However, the preliminary results presented here suggest that EpiSweep has enabled efficient deletion of broadly distributed epitopes in P99βL. If these results extrapolate to other protein targets, as we anticipate, EpiSweep should prove generally useful for the design and development of immunotolerant biotherapeutic agents. In the future, the methods could be readily expanded so as to consider other important aspects of protein immunogenicity, such as post-translational modifications and regulatory epitopes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01-GM-098977 to CBK and KEG. RSS was supported in part by a Luce Foundation Fellowship and in part by a Thayer Innovation Program Fellowship from the Thayer School of Engineering. We also gratefully acknowledge computational resources provided by NSF grant CNS-1205521. The authors would like to thank Prof. Margaret Ackerman for critical feedback on the work.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Karl E. Griswold and Chris Bailey-Kellogg are Dartmouth faculty and co-members of Stealth Biologics, LLC, a Delaware biotechnology company. They acknowledge that there is a potential conflict of interest related to their association with this company, and they hereby affirm that the data presented in this paper is free of any bias. This work has been reviewed and approved as specified in these faculty members’ Dartmouth conflict of interest management plans. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aggarwal S. What’s fueling the biotech engine - 2012 to 2013. Nat Biotech. 2014;32(1):32–39. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MP, Reynolds HM, Lumicisi B, Bryson CJ. Immunogenicity of protein therapeutics: The key causes, consequences and challenges. Self Nonself. 2010;1(4):314–322. doi: 10.4161/self.1.4.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa MD. Immunogenicity of biotherapeutics in the context of developing biosimilars and biobetters. Drug Discov Today. 2011;16(7–8):345–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer ELL, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(suppl 1):D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson CJ, Jones TD, Baker MP. Prediction of immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins: validity of computational tools. BioDrugs. 2010;24(1):1–8. doi: 10.2165/11318560-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor JR, Yoo TH, Dixit A, Iverson BL, Forsthuber TG, Georgiou G. Therapeutic enzyme deimmunization by combinatorial T-cell epitope removal using neutral drift. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(4):1272–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014739108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CY, Georgiev I, Anderson AC, Donald BR. Computational structure-based redesign of enzyme activity (vol 106, pg 3764, 2009) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(18):7678–7678. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Griswold Ke, Bailey-Kellogg C. Structure-based redesign of proteins for minimal T-cell epitope content. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23213. (1096–987X (Electronic)) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizeau J, Grenkow DM, Brown JG, Entwistle J, MacDonald GC. Engineering and Biological Characterization of VB6-845, an Anti-EpCAM Immunotoxin Containing a T-cell Epitope-depleted Variant of the Plant Toxin Bouganin. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2009;32(6):574–584. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a6981c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collen D, Bernaerts R, Declerck P, De Cock F, Demarsin E, Jenne S, Laroche Y, Lijnen HR, Silence K, Verstreken M. Recombinant staphylokinase variants with altered immunoreactivity. I: Construction and characterization. Circulation. 1996;94(2):197–206. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot AS, Scott DW. Immunogenicity of protein therapeutics. Trends in Immunology. 2007;28(11):482–490. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainza P, Roberts KE, Donald BR. Protein Design Using Continuous Rotamers. Plos Computational Biology. 2012;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding FA, Liu AD, Stickler M, Razo OJ, Chin R, Faravashi N, Viola W, Graycar T, Yeung VP, Aehle W, et al. A beta-lactamase with reduced immunogenicity for the targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics using antibody-directed enzyme prodrug therapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4(11):1791–800. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding FA, Stickler MM, Razo J, DuBridge RB. The immunogenicity of humanized and fully human antibodies: residual immunogenicity resides in the CDR regions. MAbs. 2010;2(3):256–65. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.3.11641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Friedman AM, Bailey-Kellogg C. A divide-and-conquer approach to determine the Pareto frontier for optimization of protein engineering experiments. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2012;80(3):790–806. doi: 10.1002/prot.23237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JA, Wang D, Jevnikar AM, Cairns E, Bell DA. The relationship between predicted peptide-MHC class II affinity and T-cell activation in a HLA-DRbeta1*0401 transgenic mouse model. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5(1):R40–8. doi: 10.1186/ar605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Comparison of multiple amber force fields and development of improved protein backbone parameters. Proteins-Structure Function and Bioinformatics. 2006;65(3):712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C, Garza EN, Mazor R, Linehan JL, Pastan I, Pepper M, Baker D. Removing T-cell epitopes with computational protein design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(23):8577–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321126111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippow SM, Tidor B. Progress in computational protein design. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2007;18(4):305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell SC, Word JM, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. The penultimate rotamer library. Proteins-Structure Function and Genetics. 2000;40(3):389–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor R, Eberle JA, Hu X, Vassall AN, Onda M, Beers R, Lee EC, Kreitman RJ, Lee B, Baker D, et al. Recombinant immunotoxin for cancer treatment with low immunogenicity by identification and silencing of human T-cell epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(23):8571–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405153111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazor R, Vassall AN, Eberle JA, Beers R, Weldon JE, Venzon DJ, Tsang KY, Benhar I, Pastan I. Identification and elimination of an immunodominant T-cell epitope in recombinant immunotoxins based on Pseudomonas exotoxin A. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(51):E3597–E3603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218138109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccaldon P, Argos P. Oligopeptide Biases in Protein Sequences and Their Use in Predicting Protein Coding Regions in Nucleotide-Sequences. Proteins-Structure Function and Genetics. 1988;4(2):99–122. doi: 10.1002/prot.340040204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moise L, McMurry J, Rivera DS, Carter EJ, Lee J, Kornfeld H, Martin WD, De Groot AS. Progress towards a genome-derived, epitope-driven vaccine for latent TB infection. Med Health R I. 2007;90(10):301–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moise L, Song C, Martin WD, Tassone R, De Groot AS, Scott DW. Effect of HLA DR epitope de-immunization of Factor VIII in vitro and in vivo. Clinical Immunology. 2012;142(3):320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraro PA, Vergelli M, Kalbus M, Banks DE, Nagle JW, Tranquill LR, Nepom GT, Biddison WE, McFarland HF, Martin R. Immunodominance of a low-affinity major histocompatibility complex-binding myelin basic protein epitope (residues 111–129) in HLA-DR4 (B1*0401) subjects is associated with a restricted T cell receptor repertoire. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100(2):339–349. doi: 10.1172/JCI119539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Lund O, Buus S, Lundegaard C. MHC Class II epitope predictive algorithms. Immunology. 2010;130(3):319–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Lund O. Prediction of MHC class II binding affinity using SMM-align, a novel stabilization matrix alignment method. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:238. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipovitch DC, Parker AS, Makokha CD, Desrosiers J, Kett WC, Moise L, Bailey-Kellogg C, Griswold KE. Design and analysis of immune-evading enzymes for ADEPT therapy. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2012;25(10):613–23. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzs044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AS, Choi Y, Griswold KE, Bailey-Kellogg C. Structure-guided deimmunization of therapeutic proteins. J Comput Biol. 2013;20(2):152–65. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AS, Griswold KE, Bailey-Kellogg C. Optimization of therapeutic proteins to delete T-cell epitopes while maintaining beneficial residue interactions. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2011;9(2):207–29. doi: 10.1142/s0219720011005471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AS, Zheng W, Griswold KE, Bailey-Kellogg C. Optimization algorithms for functional deimmunization of therapeutic proteins. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Kolla RV, Sidney J, Weiskopf D, Fleri W, Kim Y, Peters B, Sette A. Evaluating the immunogenicity of protein drugs by applying in vitro MHC binding data and the immune epitope database and analysis resource. Clinical & Developmental Immunology. 2013;2013:467852. doi: 10.1155/2013/467852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman DA, Case DA, Caldwell JW, Ross WS, Cheatham TE, Debolt S, Ferguson D, Seibel G, Kollman P. Amber, a Package of Computer-Programs for Applying Molecular Mechanics, Normal-Mode Analysis, Molecular-Dynamics and Free-Energy Calculations to Simulate the Structural and Energetic Properties of Molecules. Computer Physics Communications. 1995;91(1–3):1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ponder J. TINKER: Software tools for molecular design (version 6.0) 2011 doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvat RS, Moise L, CB-K, Griswold KE. A High Throughput MHC II Binding Assay for Quantitative Analysis of Peptide Epitopes. J Vis Exp. 2014a;85:e51308. doi: 10.3791/51308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvat RS, Parker AS, Choi Y, Bailey-Kellogg C, Griswold KE. Mapping the Pareto Optimal Design Space for a Functionally Deimmunized Biotherapeutic Candidate. PLoS Computational Biology. 2015;11(1):e1003988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvat RS, Parker AS, Guilliams A, Choi Y, Bailey-Kellogg C, Griswold KE. Computationally Driven Deletion of Broadly Distributed T cell Epitopes in a Biotherapeutic Candidate. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2014b:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1652-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellekens H. Bioequivalence and the immunogenicity of biopharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1(6):457–462. doi: 10.1038/nrd818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellekens H. The Immunogenicity of Therapeutic Proteins. Discovery Medicine. 2010;49:560–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidney J, del Guercio MF, Southwood S, Sette A. The HLA molecules DQA1*0501/B1*0201 and DQA1*0301/B1*0302 share an extensive overlap in peptide binding specificity. J Immunol. 2002;169(9):5098–108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H, Raghava GP. ProPred: prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(12):1236–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.12.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwood S, Sidney J, Kondo A, del Guercio MF, Appella E, Hoffman S, Kubo RT, Chesnut RW, Grey HM, Sette A. Several common HLA-DR types share largely overlapping peptide binding repertoires. Journal of Immunology. 1998;160(7):3363–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steere AC, Klitz W, Drouin EE, Falk BA, Kwok WW, Nepom GT, Baxter-Lowe LA. Antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis is associated with HLA-DR molecules that bind a Borrelia burgdorferi peptide. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203(4):961–971. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Still WC, Tempczyk A, Hawley RC, Hendrickson T. Semianalytical Treatment of Solvation for Molecular Mechanics and Dynamics. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1990;112(16):6127–6129. [Google Scholar]

- Sturniolo T, Bono E, Ding J, Raddrizzani L, Tuereci O, Sahin U, Braxenthaler M, Gallazzi F, Protti MP, Sinigaglia F, et al. Generation of tissue-specific and promiscuous HLA ligand databases using DNA microarrays and virtual HLA class II matrices. Nat Biotech. 1999;17(6):555–561. doi: 10.1038/9858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombetta ES, Mellman I. Cell Biology of Antigen Processing in vitro and in vivo. Annual Review of Immunology. 2005;23(1):975–1028. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Sidney J, Dow C, Mothe B, Sette A, Peters B. A systematic assessment of MHC class II peptide binding predictions and evaluation of a consensus approach. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4(4):e1000048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver JM, Sant AJ. Understanding the focused CD4 T cell response to antigen and pathogenic organisms. Immunologic Research. 2009;45(2–3):123–143. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung VP, Chang J, Miller J, Barnett C, Stickler M, Harding FA. Elimination of an Immunodominant CD4+ T Cell Epitope in Human IFN-β Does Not Result in an In Vivo Response Directed at the Subdominant Epitope. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(11):6658–6665. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.