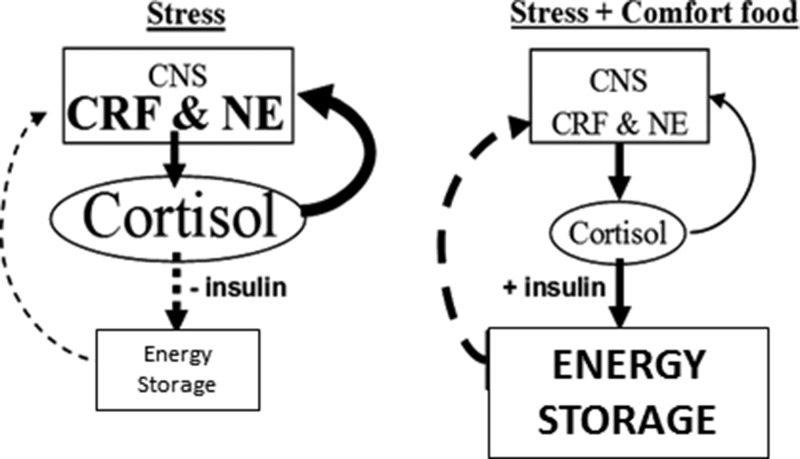

Figure 1.

Metabolic-brain feedback model. Solid lines are stimulatory; dashed lines are inhibitory. During stress, the feed-forward actions of cortisol on brain stress pathways [eg, CRF, norepinephrine (NE)] promote palatable feeding, increase anxiety and fear, and stimulate activity in the sympathetic nervous system and HPA axis (6). Reduced feeding during stress decreases insulin, rendering cortisol, along with increased sympathetic nervous system outflow, catabolic in the periphery. Decreased energy storage disinhibits metabolic feedback and perpetuates the feed-forward actions of cortisol. However, with the ingestion of highly energetic comfort foods, increased cortisol stimulates insulin and energy storage, which feeds back to inhibit activity in the HPA axis and reduces cortisol output and its feed-forward effects, temporarily providing relief from stress. If the source of stress is not removed, continued self-medication in this fashion might lead to central obesity. Consistent with the concept that chronic stress increases allostatic load (23), the relative impact to brain stress pathways of the metabolic-feedback signal (ie, energy reserve or net anabolic activity) may decrease with chronic stress, thereby increasing the signal magnitude needed to impart its feedback effects; ie, tolerance might be developed. [Reproduced from M. Dallman et al: Chronic stress and obesity: a new view of “comfort food.” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(20):11696–11701 (14), with permission. ©The Endocrine Society]