Abstract

The rapid development of analytical technology has made lipidomics an exciting new area and this review will focus more on modern approaches to lipidomics than on earlier technology. Although not fully comprehensive for all possible brain lipids, the intent is to at least provide a reference for the analysis of classes of lipids found in brain and nervous tissue. We will discuss problems posed by the brain because of its structural and functional heterogeneity, the development changes it undergoes (myelination, aging, pathology etc.) and its cellular heterogeneity (neurons, glia etc). Section 2 will discuss the various ways in which brain tissue can be extracted to yield lipids for analysis and Section 3 will cover a wide range of techniques used to analyze brain lipids such as chromatography and mass-spectrometry. In Section 4 we will discuss ways of analyzing some of the specific biologically active brain lipids found in very small amounts except in pathological conditions and section 5 looks to the future of experimental lipidomic modification in the brain.

Keywords: Brain lipids, Phospholipids, Sphingolipids, Mass-Spectrometry

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The brain contains an incredible mixture of lipids and has been a focus for lipid chemists since brain cholesterol became the first organic compound to be purified (crystallized) in 1834. It has continued to attract attention since both genetic diseases and common neurodegenerative diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis, leukodystrophies, Parkinsons, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, glioblastomas and Alzheimers have been associated with disturbances in brain lipid content. Thus a normal MRI reveals uniform lipid-rich structures and pathology whereas In multiple sclerosis MRI reveals Dawson fingers, a radiographic feature resulting from loss of lipids and demyelinating plaques through the corpus callosum (Fig.1A, B). They are arranged at right angles along medullary veins (callososeptal location) and give some clues that lipids have a definite organization in the brain and that they are worthy of being measured in great detail. A more accentuated demyelination is shown in Fig.1 panel C. This is of a patient with a leukodystrophy of unknown etiology, which has destroyed many brain lipids. Many such changes may not be causative but may be associated with inflammation or other degenerative processes but in all cases, a lipid analysis can start the pathway to diagnosis and possible therapy.

Fig.1.

A crude way of measuring lipids by magnetic resonance images of human brain . These show even lipid distribution in controls (A) and the abnormal lipid composition and shrinkage of the brain associated with neurodegeneration (B,C).

The rapid development of analytical technology has made brain lipidomics an exciting new area and this review will focus more on modern approached to lipidomics than more outdated technology which will be referenced but not discussed in any detail. The brain poses unique sampling problems due to developmental changes (especially myelination) and aging, rapid turnover rates of some lipids and cellular heterogeneity. This is reflected in the changes in major lipids during the aging process. Thus in human brain (Fig.2), Phosphatidylcholine (PC) predominates at birth (50%) but then declines and sphingomyelin (SM) increases from 2 to 15% at 3 years, consistent with its role in the myelin sheath and mature membranes. Less attention has been paid to the problem of metabolic instability post-mortem, perhaps because many initial studies were done on human autopsy material. Methods now exist for rapidly freezing or denaturing mouse brain and with increasing interest in phosphorylated lipids, which tend to have a short half-life, we may see more attention to this area in the future. What has been a focus of attention since the very early days is that molecular oxygen is destructive to polyunsaturated fatty acids, generating reactive lipids such as 1-palmitoyl-2-(5”-oxovaleryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine) from brain phosphatidylcholines. Thus most extraction procedures are careful to keep extracted lipids either in solvent or dried down and stored under under nitrogen.

Fig 2. The phospholipid content of control human brain with age.

Phosphatidylcholines (PC) are 50% at birth, declining to 25% at age 8 whereas sphingomyelin (SM) (Ceramidephosphorylcholine) increases from 2% to 16% over the same time period. In contrast, phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) show modest increases over the same time-period. Extracted brain lipids were resolved by 2D HPTLC and qualified by lipid phosphorus analysis according to Rouser [1]. Such analyses do not take into account any regional differences in lipids, fatty acid chain length heterogeneity degree of unsaturation, plasmalogen content and other metabolic modifications.

The cellular heterogeneity of brain is equally dramatically variable so sampling differences have complicated the quantitative analysis of brain lipids in the past. The individual cell types (neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes etc.) all have their very distinctive lipid composition. Thus complex gangliosides are typical of neurons and galactosylceramides are uniquely expressed by oligodendrocytes and this has to be taken account of in any attempt to quantify “brain lipids”. The problem of sampling different brain regions is a critical part of measuring brain lipids and we will discuss new technology (MALDI) that has been developed to solve this problem. Some brain lipids are also highly metabolically dynamic, so that post-mortem changes can add to the complexities of interpretation, as well as lipid levels being affected by diet and general health–related issues such as malnutrition, metal toxicity etc.). The genes for the enzymes responsible for the synthesis and metabolism of most brain lipids are known and the use of knock-out mice in conjunction with HPLC/MS/MS has started to reveal some structure-functional insights as well at the complexity of the metabolic connections between lipids.

Most early lipid analyses were done on human autopsy tissue in an endeavor to provide diagnostic help to clinicians. A good example would be the increased brain sphingomyelin found in Niemann-Pick disease and the specific ganglioside accumulations in Tay-Sachs (GM2-gangliosidosis) and GM1-gangliosidosis, which was first observed more than 50 years ago. Fig.3 shows the diagnosis of Tay-Sachs disease on the basis of the accumulation of GM2 ganglioside primarily in neurons [2,3].

Fig 3.

Panel A: HPLC analysis of a brain with a genetic deficiency of N-acetyl-b-D-galactosaminidase A (commonly called Tay-sachs disease. Lane 1 (NORM) is control brain gangliosides from the same amount of brain tissue as Lane 2. Lane 2 (AFF) shows GM2 ganglioside to be >95% of total gangliosides compared to control For a detailed discussion of ganglioside structures see [2,3]. For a detailed discussion of how GM2 is quantified see [6-8]. Panel B: Luxol stained gray matter from a brain with a lipid storage disease showing morphological evidence of massive lipid accumulation in neurons, which become grossly swollen and dysfunctional around 6 months of age. . Panel C: shows unstained gray matter from a brain with a genetic deficiency of tripeptidylpeptidase 1 (CLN2), late infantile Batten disease showing massive neuronal storage of autofluorescent pigment which is brain-specific and clinically similar to Tay-Sachs disease (initial normal behavior followed by a rapid decline in function after 6 months) but the lipid storage material remains uncharacterized

In this review I will attempt to focus on the issues, solutions, techniques and future direction of 180 years of brain lipid measurements.

2. Pre-analytical work-up

2.1) Homogenization and extraction techniques

The exact extraction method may vary but after 50 years of research all extraction methods involve a mixture of polar and non-polar organic solvents, most commonly chloroform and methanol (the Folch procedure [4] or the Bligh and Dyer procedure [5]). Total lipids are typically extracted from half brains of mice or 0.1g of other brains by homogenization in 3 mL of PBS, followed by protein standardization. Age-matched samples are essential since myelination increases with age and myelin is greatly enriched in lipids. [7]. Lipids are extracted by adding methanol (5 mL) and incubating at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by the addition of 1 drop of conc. HCL and chloroform (10 mL) to achieve the Folch partition in which most of the lipids are in the lower phase and the gangliosides in the upper phase (C-M-water 1:47-48), also known as “theoretical upper phase.

The Bligh and Dyer initial approach [5] is to add CHCl3 and CH3OH (1:2 v/v) to a 1 ml. sample, vortex and then add 1.25 ml of CHCl3 and 1.25 ml of water, vortexing well. Most of the lipids will be in the lower phase, which is removed with a pipette. The phases can each be washed with a theoretical upper or lower phase and combined and concentrated before HPTLC (Fig.3A)

For ganglioside isolation from the upper phase, prior to HPTLC it is necessary to get rid of salt, usually with a Sep-Pak or Lichoprep column and any traces of detergent. Typically, following extraction of fresh or frozen brain tissue with 20 volumes of Chloroform-methanol-water (4:8:3 v/v), water is added to make a final ratio of 4;8:5.6 v/v [6]. The lower phase is partitioned twice with water and this is combined with the upper phase. The lower phase is used for total lipid analysis and the aqueous (upper phase) is desalted on a c18 reversed phase (eg: Lichoprep 0.3g/g brain wet weight) and analysed for more hydrophilic lipids such a sgangliosides [7]. Gangliosides are eleuted with methanol after extensive washing with water. The dried extract is treated with 0.6N NaOH to destroy any trace phosphoglycerides and repurified on the column as indicated above. For gangliosides, further purification on DEAE-Sephadex can be done if necessary. [7-9].

2.2. Isotope-labeling

Pre- 1960s, the direct injection of isotopic precursor intracerebrally into live rodents was used to label lipids for quantification and for use as substrates for lysosomal hydrolase assays. For example, to make [3H]-sphingomyelin for use in sphingomyelinase assays for diagnosis of Niemann-Pick disease, the rat was made choline-deficient and just before death was injected with 3H-choline. The [3H]-SM was extracted from the brain as described above and cleaned up on a column. Other lipids can be labeled by general precursors such as [3H]-palmitate [36] or specific precursors such as [3H-inositol] for polyphosphoinositides[10] and these are now all obtainable from commercial sources. However, such studies led to the realization that minor species of lipids , such as the phosphatidylinositides were complex and important signaling lipids in the CNS [10]. It is also possible to use [32P] in order to label all phospholipids for quantification by x-ray film exposure and scanning densitometry [11], for example Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5P3 but this isotope-labeling approach has largely been replaced by Mass-Spectrometric (MS/MS) analysis.

2.3. Stable isotopes and prostaglandins

Known amounts of Deuterated analogs of specific lipids can be added to brain extracts during the extraction procedure and used to measure the levels of minor but highly bioactive lipids such as prostaglandins at the femtomolar level. Quantification is then achieved by Mass spectrometric ratio analysis of the hydrogen to deuterium ratio (a difference of one mass unit)[12]. Currently the analysis of prostaglandins is done by Ultra-high-performance/pressure HPLC MS/MS. Using this approach, the metabolites of arachidonic acid (AA) (prostanoids), and from the CytochromeP 450 pathway, (eicosanoids), can be quantified by a UPLC-MS/MS system, which simultaneously measures 11 prostanoids in rat brain cortical tissue [12]. Using improved processing and extraction conditions resulted in an overall improvement in extraction recovery and reduction in matrix effects at low concentrations. Rat brain cortex contained prostanoids at 10.2 to 937pmol/g and eicosanoids ranged from 2.23 to 793 pmol/g wet tissue. With this technique it may become possible to further delineate their role in brain functions. However, with such short half-lived metabolites it is critical to rapidly kill enzymes with microwaves or liquid nitrogen to prevent post-mortem changes. This is a major problem with all lipids, especially lipid phosphates such as sphingosine-1-phosphate.

The addition of known amounts of stable isotope lipid homologs can be used for measuring all types of brain lipids. Thus Saito et al [12] extracted lipids from rodent right cerebral hemisphere tissues (150 mg) by homogenizing with zirconia beads in 1 mL of methanol at 4°C using a cell disruptor before adding appropriate internal standards. Examples of such “standards” would be (1, 2-dipalmitoyl D6-3-sn glycerophosphatidylcholine (16:0/16:0PC-d6, 40 nmol/10 mg tissue, 1,2-caprylin-3-linolein (250 pmol, 13C-labelled tripalmitin (tripalmitin-1,1,1-13C3, 250 pmol , deuterated prostaglandin E2 (PGE2-d4, 5 ng) and deuterated leukotriene B4 (leukotriene B4-d4, 5 ng ). Chloroform, methanol and 20 mM potassium phosphate (Kpi) buffer was then added to achieve a volume ratio of buffer/methanol/chloroform of 0.8:2:1, and mixed vigorously for 5 min. before adding 1 ml each of chloroform and 20 mM Kpi buffer. After centrifuging at 1,000 × g for 10 min. both the upper aqueous layer and bottom organic layer are collected. To distinguish alkenylacyl and alkyl PL species with the same exact mass as 34:1 ethanolamine plasmalogen (pPE) and 34:2 alkylacyl PE, a small aliquot of each sample must be hydrolyzed with 0.5 N HCl and the resistant species reanalyzed. Total lipid samples are typically analyzed by electrospray ionization (ESI)-TOF Mass Spectrometry interfaced with a UPLC System or LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer interfaced with an HPLC system. Many Labs are employing similar approaches to quantify minor lipids where stable isotope standards are available.

2.4 Dolichol sugars

Despite 50 years of effort no disease-specific lipid accumulation has been found in the brains of children with Batten disease (Neuronal:Ceroid lipofuscinosis) apart from an autofluorescent peptidolipid complex, consisting mainly of the hydrophobic peptide, subunit C of mitochondrial ATP synthase. Abnormal lipids have been found in the brains of such children with Battens disease types CLN1, 2 and 3 but they are apparently not directly connected to the function of the product of the gene which is mutated. These unusual lipids (C100-dolichol sugars) (Fig.4) are normally transiently involved in the synthesis of N-linked glycoproteins and require a specific pre-analytical work-up involving sodium [3H]borohydride labeling of aldehyde groups. This approach can be used for many types of lipid analysis where aldehyde formation is involved, such as lipid peroxidation [13].

Fig 4. Relative amounts of [3H]Man (5-9 residues)GlcNAc2 oligosaccharides liberated from stored Dolichol oligosaccharides in gray matter from patients with 3 forms of Batten disease.

CLN1 (infantile) patient with a complete deficiency of palmitoyl:protein thioesterase 1, and CLN3 (Juvenile) patient. CLN1 patients show all 5 major forms whereas Man7 and Man8 forms are less in CLN2 and CLN3 forms.

Dolichols are themselves synthesized from cholesterol precursors such as farnesyl and geranyl-geranyl phosphates. Because these lipids are unusual, brain homogenates are first delipidated by extraction twice with 2 vols. of butanol: diisopropyl ether (2:3). Chloroform and methanol (3:1.5) is added to the lower phase, the upper phase discarded and the lower phase washed, ending up with the dolichols in Chloroform-methanol-water 1:1:0.3. The extraction is repeated, combined and oligosaccharides released from extracts by mild acid hydrolysis or endo-H treatment [13]. The liberated oligosaccharides are then radiolabeled with [3H]sodium borohydride and subjected to HPTLC in butanol-acetic acid-water (2;1:1.5). Elevated levels of a range of dolichol sugars (Fig. 4) are typical of CLN1,2 and 3 forms of Batten disease but not other lysosomal storage diseases. However, despite our ability to quantify them, the mechanism of their formation remains unknown.

2.5. Preparation for staining brain sections with brain lipid specific antibodies such as A2B5 or O4A (oligodendrocytes) [15]

Neonatal Rat Hippocampal slices or individual neural cell cultures can be fixed to gel-coated slides using paraformaldehyde with Gold Antifade containing DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole), a nuclear stain that binds strongly to A–T-rich regions in DNA. Neuronal staining is carried out with Nissl body staining such as NeuroTrace which binds to negatively charged nucleic acids in the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) of neurons [14]. A monoclonal antibody RIP (receptor-interacting protein) antibody which specifically recognizes 2’,3’-cyclic nucleotide 3’-PDE (phosphodiesterase) stains oligodendrocytes [15] as does A2B5 (probably sulfated ganglioside) and O4A (GalCeramide). GFAP stains astrocytes and iso-lectin stains macrophages [15]. Methods have been developed for the quantification of stained material (Image J) and this approach can be used to measure lipids if the antibody is specific for a given lipid.

2.6. Isolation of lipid-rich microdomains from brain

The functional role of lipids in the brain is becoming more appreciated and a better understanding of their role in cell membranes is slowly being achieved. In most cell plasma membranes, cholesterol condenses the packing of sphingolipids and glycerolipids to form microdomains and many critical cell functions such as binding of ligands to 7-transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptors, both occur in and around these microdomains and control the signaling processes downstream of the receptors [16]. Microdomain lipids constitute a less fluid, liquid ordered phase which is separate from the phosphatidylcholine/ PS/PE-rich liquid-disordered phase in the exofacial (inner) leaflet of the membrane [16] and the amounts of each lipid control the biophysical properties of the membrane. These lipid domains are also the port of entry for viruses infecting human cells, such a HIV and Ebola virus and hence are of considerable current interest. Microdomain isolation prior to analysis can be used to amplify minor constituents of the brain lipidosome prior to analysis and help resolve structural lipids from signaling, secretory or endocytic lipids.

Raft Lipids are also important since they can regulate the conformation and function of many GPI-anchored proteins such as flotillin, MOG, etc as well as neurodegeneratively important proteins such as prions and Amyloid precursor protein. The relative ease of isolation of microdomain lipids by virtue of their insolubility in Triton X-100 at 4°C and their buoyancy on sucrose density gradients has proved to be a useful pre-step for brain lipidomic studies. Thus, lipids from brain samples (50mg fresh weight of mouse cerebral hemisphere) are extracted with 2ml of 1% TritonX-100/MES buffer-NaCI (pH 6.5) using 50 strokes of a Dounce homogenizer. Following low-speed centrifugation at 700g to remove debris and insoluble myelin material, the lipids are ready for extraction. Myelin can be a big problem in older animals. If microdomains are to be isolated, the supernatant is mixed with 2ml of 1% Triton X-100 in 80% sucrose/MES buffer and placed in an ultracentrifugation tube. 5 ml of 30% sucrose/MES is layered on top of this fraction, followed by 3 ml of 5% sucrose/MES and the samples ultracentrifuged at 39,000xg for 17h. One ml fractions are collected and typically, an opalescent band is seen in Fraction 4 which contains >95% of LR protein markers such as Flotillin-1 [17]. The ten to twelve, 1 ml fractions removed from the top of the tube are dialysed to remove sucrose and detergent if HPTLC is to be performed. Otherwise, samples of these fractions are subjected to direct lipid analysis by cleaning up with HPTLC prior to MS analysis. Extraction of “microdomains” (aka Lipid rafts) from human cortex showed approximately 20% of the cholesterol, 38% of the sphingomyelin and 95% of glycolipids to occur in such microdomains compared to 2% of brain protein and 8% of total phospholipids. In a study on mouse brain cerebral cortex we showed that Sphingolipids varied dramatically in fatty acid composition (including hydroxylation in GalCer) but that both C18:1/C18:0 Sphingomyelin (SM) and Galactosylceramide (GalCer) (C18:1/C24:1)were >95% in lipid rafts whereas lipids such as bis(monoacylglycero)phosphate (BMP) (C22:6) which are involved in endosome-lysosome trafficking in the brain were absent from lipid rafts [17] (Fig.5).

Fig 5.

Quantification of the major sphingomyelin (SM C18:1/18:0) (A) and major galactosylceramide (C18:1/24:1) in mouse brain after Fractionation to isolate microdomains (lipid Rafts) (Fraction 4). The major form of BMP(22:6/22:6) is essentially absent from lipid microdomains.

With PtdChol, the more unsaturated the fatty acid the less it appears in lipid raft microdomains (Fig.6). The dynamic nature of myelin, a unique brain structure, both helps and complicates measuring brain lipids in young animals but its high hydrophobic protein and sphingolipid content has helped concentrate some of the quantitatively minor but functionally important brain glycolipids such as sphingosines and Spihgosine-1-phosphates. The special pre-analytical methods devised to get rid of hydrophobic proteins are less important now that MS is commonly used for analysis.

Fig 6.

Quantification of 3 forms of phosphatidylcholine (PC) showing A: C16:0/C16:0 mainly in microdomains (Fraction 4), B: PtdChol C16:0/18:1 equally in both and C: PtdChol C16:0/18:2 predominantly in non microdomains.

3. Techniques for measurement of lipid levels in brain

3.1 Thin-layer chromatography of total lipids

Following lipid extraction (see Section 2) the upper phase is collected and the lower phase washed three times with an equal amount of theoretical upper phase (TUP) (methanol:water:chloroform (48:47:3)). The three TUP washes are pooled with the original upper phase, evaporated to dryness, resuspended in 200 μL water, and sonicated. Chloroform:methanol (6 mL, 2:1 v/v) is added, the sample vortexed and evaporated to dryness with nitrogen. This step is repeated several times to remove hydrophobic acylated proteins such as Proteolipid protein. Gangliosides in the upper phase are desalted on a sep-Pak column and resolved on Whatmann HPTLC plates (10 cm × 10 cm LHP-K TLC plates) by two sequential developments in chloroform:methanol:0.25% KCl (50:40:10) followed by charring with 10% CuSO4-8% H2SO4. (Fig 7) or chromophore formation (resorcinol for gangliosides, orcinol for all sugars)[6,7,19,20]. The amounts can be quantified by densitometry and the use of lipid standards of known concentration.

Fig 7. HPTLC of lower phase lipids.

Standards are PC (phosphatidylcholine), lPC (lyso-PC), SM (Sphingomyelin), Cer (Ceramides), GC (Galactosyl ceramides), and S (sulfatides).

Lanes 6-8 CLN2 – Batten disease, CD (Canavans disease), C (Control) Total Lipids Lanes 9-11 sphingolipids after alkaline methanolysis to remove glycerophospholipids. Note: the loss of myelin lipids (GC& S) in Canavans Leukodystrophy but not from CLN2 brain. The individual lipids are quantified by densitometry by reference to known amounts of standards (SM etc.).

3.2 Analysis of Sphingolipids by high performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC)

For sphingolipids, the lower (organic) phase is evaporated to dryness under nitrogen and subjected to alkaline methanolysis to remove phosphoglycerides (1mL of 0.6N NaOH for 1 hr). Following neutralization with 70 μL of concentrated HCl, salts are pelleted, CHCl3 (2 mL) and water (0.6 mL) added to the supernatant, the upper phase removed and the lower phase washed with an equal amount of TUP to remove salt. The lower phase is evaporated to dryness, lipids applied to HPTLC plates and developed in chloroform:methanol:glacial acetic acid:water (70:25:8.8:4.5 v/v). Ceramide, glycosylceramides, and SM are visualized by charring with 10% CuSO4–8% H2SO4. Quantification is by densitometry using authentic lipid standards [19,20].

3.3 Column chromatography for lipid fractionation

Silicic acid (Unisil) columns were once extensively used to fractionate lipids prior to HPTLC. After dissolving in CHCl3 the run-through lipids in CHCl3 were Cholesterol, Cholesterol Esters, Triglycerides, Free FattyAcids etc., which could then be quantified by HPTLC, MS etc. The second elution, Chloroform:Methanol (98:2v/v) contains ceramides. Acetone:Methanol (9:1) then elutes glycolipids [23] and Methanol elutes phospholipids [23]. These techniques have been largely superceded by HPLC prior to MS/MS as discussed later.

3.4. High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC)

The preparative and analytical separations of glycolipids and phospholipids by conventional column or thin-layer techniques can be tedious and time-consuming processes and so high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was developed [21] for the purification and analysis of separate lipid classes and their molecular species. HPLC technology requires the use of injection ports for sample application, reusable columns packed with microparticulate stationary phases, pumps for uniform solvent flow, heating and online sample detection. Most lipids are separated by normal-phase HPLC according to their polarities, followed by reversed-phase HPLC according to their nonpolar moieties. Argentation permits the resolution by their degree of unsaturation. Glycolipids do not possess a functional group that permits their detection so they must be derivatized with benzoyl chloride or benzoic anhydride to form stable, UV-sensitive derivatives. These days, HPLC is almost always coupled to MS/MS. For a detailed discussion of lipid analysis by HPLC see [21].

3.5 Analysis of brain lipids by gas-liquid chromatography (GLC)

This analysis of many lipids became possible in the 1960s with the advent of gas-liquid chromatography. For glycolipids, the key step was the initial methanolysis followed by extraction of fattya cid methyl esters with hexane and the conversion of methanol-soluble non-volatile sugars and some lipids to trimethylsilylether derivatives through hydroxyl groups. Thus it was very useful for glycolipid analysis [23] because the sugars could be qualitatively and quantitatively analysed on SE-30 columns (using a mannitol internal standard) and hydroxy fatty acids could be separated from Non-hydroxy fatty acids. Unusual lipids such as the isoprenoid phytanic acid (3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadecanoic acid) which is of plant origin could be shown to accumulate in the brains of patients with Refsum's disease [22] allowing a precise diagnosis to be made. Such GLC analyses are now more easily accomplished by Mass-Spectrometry

3.6. Analysis of brain lipids by GLC-Mass-Spectrometry

The initial combination of GLC and MS, using the LKB9000 following the conversion of lipids to more volatile derivatives such as the trimethylsilylethers or permethylated sugars was useful for measuring glycosphingolipids [24], and for metabolic studies using deuterated analogs of sugars in glycolipids and following metabolic fate by the difference in mass units. The use of MS was immeasurably enhanced by improvements in data handling from manual (1968), light–sensitive recording paper with included molecular ion size (1969) to digital storage of data beginning with a PDP-8I and paper punch cards (1970 and beyond). Further automation has clearly made MS a dominant technique and its role in analaytical chemistry has been further enhanced by the development of ionization technology such as electrospray ionization (ESI). (Fig.8) and MALDI.

Fig 8. Three Ages of Mass-Spectrometry – Lipidomics.

Panel A: University of Pittsburg 1967: LKB 9000 gas-chromotograph (GLC) mass spectrometer with Ryhagge separator and manual identification of m/e peaks.

Panel B: Michigan State University 1969: LKB 9000 GLC-MS with computerized (punch card) data analysis (PDP8I occupying most of the room.

Panel C: University of Chicago 2005: HPLC hybrid triple quadruple/linear ion trap MS with electrospray ionization and a much better data acquisition system!

3.7 HPLC/MS/MS using electrospray (ESI)

Most MS analyses use the Bligh and Dyer method [5] for lipid extraction. A lipid can be identified and quantified if a standard is available to determine the signal response from the fragmentation pattern, but this imposes certain obvious restrictions if a novel lipid is to be identified. Thus MS is never the method of first-resort for lipid analysis of a complex mixture. Extracted brain lipid samples are made up to 0.1 ml and an internal standard mix (0.024ml) containing 400pmol of the following non-physiological lipids is added. For example this could contain Ceramide (d18:1/C17:0), Glucosyl-Ceramide (d18:1/C16:0d3), Lactosyl-Ceramide (d18:1/C16:0d3), phosphatidylcholine (14:0/14:0), Phosphatidylglycerol (14:0/14:0), BMP (14:0/14:0), phosphatidylinositol (14:0/14:0), GM2 ganglioside, and cholesterol ester (17:0).Some ganglioside analyses can be performed separately using GM1b as internal standard. The mixture is then shaken for 10 min following addition of CHCI3: CH30H (2: 1 v/v), water (0.4 ml) added and the biphasic mixture separated and concentrated under nitrogen gas at 40 degrees C. Samples are reconstituted in methanol containing 20mM ammonium formate and 0.06ml aliquots put into 96 well microtiter plates for automated analysis. Cholesterol is determined by reference to a cholesterol ester 17:0 internal standard after conversion to cholesterol ester by addition of 0.2 ml of acetylchloride:CHCl3 (1:5 v/v). (Fig.9).

Fig 9.

Inter-related pathways of sphingolipids and dihydrosphingolipids which can all be quantified by various types of mass-spectrometry. Quantification depends largely on how fast the brain tissue can be extracted following removal of the brain.

Samples are cleaned up by HPLC to remove traces of detergent and for analysis of minor lipids such as BMP (lyso-bis-phosphatidic acid). Samples are additionally cleaned up with an Altima C18 column to remove major lipids such as PtdCholine [25] and then analyzed by ESI-MS/MS with, for example, a PE Sciex API 3000 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a turbo-ion-spray source (200°C) and Analyst 1.1 data acquisition system [25]. Relative brain lipid levels are determined by relating peak area to the internal standard. Sphingolipids (Cer, and glycosylceramides etc.) are quantified in the positive ion mode using the m/z product ion of 264 corresponding to the sphingosine base and for SM and phosphatidylcholine the m/z product of 184 corresponding to the phosphocholine head group. Other phospholipids can be quantified in the negative ion mode by using the m/z product ions corresponding to the appropriate fatty acid. This method has the ability to measure >400 major lipid species in a single sample and more details can be found at [25].

3.8. Use of MS/MS to quantify pathological events involving Sphingoid Bases, Sphingoid Base 1-Phosphates and Ceramides

Sphingosine bases are rapidly acylated and deacylated and interconverted in the brain (Fig.9) so time is a factor in attempts to measure their levels in response to various drugs or stimuli. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is extracted by a modified Bligh and Dyer [5] procedure with the use of 0.1N HCl for phase separation. C17-S1P (40 pmol), C17-Sph (30 pmol), and 17:0-Cer (30 pmol) are added as internal standards during the initial step of lipid extraction and the extracted lipids are dissolved in methanol/chloroform (4:1, v/v), Aliquots are taken to determine the total phospholipid or protein content and concentrated under a stream of nitrogen, redissolved in methanol, transferred to autosampler vials, and subjected to consecutive LC/MS/MS analysis. A typical approach is to use an automated Agilent 1100 series liquid chromatograph and autosampler (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE) coupled to an API4000 Q-trap hybrid triple quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) equipped with a TurboIonSpray ionization source. Sphingolipids are ionized via electrospray ionization (ESI) with detection via multiple reactions monitoring (MRM) [26]. For sphingoid bases and the molecular species of ceramides we use ESI in positive ions with MRM analysis. The standard curves are linear over the range of 0.0–300 pmol of each of the sphingolipid analytes with correlation coefficients (R2) > 0.98. A typical use of this approach would be to follow the changes in brain following stroke or subarachnoid hemorage when dihydrosphingolipids build up (43) and distort sphingoid base homeostasis.

3.9. Shotgun MS/MS analysis

Pioneered by Gross and Xianlin Han for lipid analysis at Washington University, shotgun MS allows a wide spectrum of brain lipids [27-29] to be studied. Lipids are extracted by a modified Bligh and Dyer using 50 mM LiCl in the aqueous phase and internal standards such as 16:0-16:0 GPEtn, 14:1-14:1 GPCho, 15:0-15:0 GPSer, 15:0-15:0 GPGro, 17:0 ceramide, 16:0 sulfatide, d35-18:0 GalCer, and 12:0 SM. The brain lipid extracts as described earlier are concentrated under non-oxidizing conditions, filtered, and re-extracted with 20 mM LiCl as previously described [26]. Early ESI/MS analyses were carried out with a ThermoElectron TSQ Quantum Ultra (Thermo Electron Corp., San Jose, CA) using 2 min signal averaging in the profile mode [41]. (Fig.10)

Fig 10. Shotgun MS reveals novel sphingolipids such as hydroxyglucosylceramide unique to oligodendrocytes.

Panel A Lipid analyses of PE, PC, lysoPC, PS, and PG in brain from a mouse with null ceramide :galactosyl transferase showing minimal lipid changes in five phospholipids.

Panel B: Shotgun MS lipid analysis of SM (no change) but GlyCer – big reduction, Sulfo-GalCer (sufatide-absent) but ceramide no change. The reason that some GlyCer is detected in CGT-/- brain is that Glucosylceramide appears identical to GalCer by MS/MS but with mainly C22/24 alpha-hydroxy fatty acids, and is exclusively found in oligodendrocytes. GalCer and GlcCer can be resolved by HPTLC either after impregnating TLC plates with sodium tetraborate or using HPTLC to resolve GlcCer from Galcer (normally in excess by 500:1) as a faster moving band.

To achieve the analysis of multiple lipids by shotgun MS/MS, certain conditions must be met:

-

i)

For anionic lipids (e.g., anionic phospholipids and sulfatide), the negative-ion mode is used.

-

ii)

Addition of a small amount of LiOH in methanol prior to infusion facilitates the analysis of choline glycerophospholipids and sphingomyelins as their lithium adducts in the positive-ion mode.

-

iii)

This also permits the analysis of ethanolamine glycerophospholipids in the negative-ion mode [29]. Individual lipid molecular species are identified by multi-dimensional mass spectrometry as previously described [29].

Shotgun lipidomics identifies a large number of different lipids in a few runs and can verify differences between neurons and oligodendrocytes, such as the presence of sulfatide and GalCer in oligodendrocytes and their absence from neurons (Fig.10). Whole the sphingoid base is C18:1 in all cases, one can also clearly see that the fatty acid composition is heterogeneous, with major forms C18:0 (38%), C24: 1 (25%), C24:0 (20%) and C16:0 (12%) and minor forms of C20:0. C22:0. C22:1 and C23:0. Fatty acid composition of Cer correlates quite well with that of GalCer, apart from the conversion to alpha-hydroxy C24:0 in GalCer. This suggests a precursor-product relationship between Cer and GalCer in NRO, which involves subsequent alpha-hydroxylation during or after GalCer synthesis. Sulfatide was even more heavily enriched in longer chain fatty acids and alpha-hydroxy fatty acids, than GalCer its presumed precursor (Fig.11). In contrast, the quantitatively dominant Sphingomyelin ( The ratio of SM to Cer is 9:1) is much more homogeneous (predominantly C16:0 (48% compared to 12% in Cer) and C18:0 (20% compared to 38% in Cer). Other major fatty acids were C24:1 (15%), C24:2 (14%) and C18:1 (8%) but no alpha-hydroxy fatty acids were present. Although there is no clear precursor-product relationship between Cer or Gal-Cer and SM, the relationship is much closer than to any phosphoglycerides. The technique is not so good for measuring S1P etc so it is best to choose a MS method based on the specific lipids of interest. These myelin lipids are often difficult to reliably quantify in human brain because of age/pathology/sampling differences.

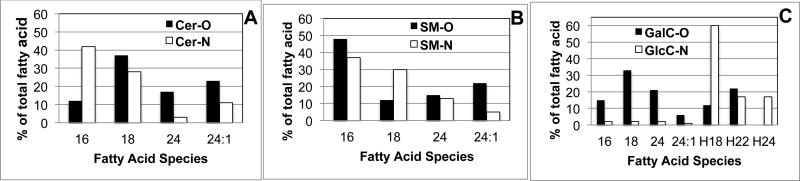

Fig 11. Variability of sphingolipid fatty acid composition between rat neurons (N) and oligodendrocytes (O).

Panel A: Ceramide (Cer) showing increased C16 in oligodendrocytes (O) and increased C 24:0 and 24:1 fatty acids in neurons ( N).

Panel B: sphingomyelin (SM) showing increased C18 in Neurons and increased C24:1 in Oligodendrocytes.

Panel C: Galactosyl ceramides (GalC) found only in Oligodendrocytes (O) and glucosyl ceramides (GLC Cer) found only in Oligodendrocytes.

Why is brain phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) so heterogeneous?

Using the Xianalin Han shotgun lipidomics approach [27-29] it is easy to identify 38 species of PE from a mouse brain extract. As seen in Fig.12, the individual variation between normal mouse brain cortex (open box) and a mouse brain in which Akt has been overexpressed (closed box) and the myelin volume is about 10% increased over normal), is fairly minor. The fatty acids are separated into plasmalogen (P) (vinyl ether) forms (P) and a wide range of typical fatty acids (D), many polyunsaturated, and many that cannot be completely identified at this time.

Fig. 12.

Shotgun Lipidomic analysis of phosphatidylethanolamine species from normal mouse brain and mice overexpressing Akt and having 10% increased myelin. Samples were generously supplied by Dr. Wendy Macklin, University of Colorado Medical Center, Denver, CO.

3.10 MALDI-TOF MS/MS

The basic problem with MS is that you measure what you are looking for, typically obtaining lipid quantification by including an appropriate non-physiological analog as a standard. Thus MS/MS should not be the technique of first resort in a new system and only gives an average when analyzing a complex tissue such as the brain. This can be overcome by combining the technique with HPTLC but sensitivity is lost because the laser does not penetrate the silica gel of the HPTLC plate [30]. However, the development of MALDI-MS has overcome many of these problems. As with other Mass-Spectrometric analyses, lipids are extracted by Chloroform-Methanol-Water, (plus one drop of conc. HCl to prevent formation of phosphatidylmethanol). The Folch (2:1:0.6 v/v) partition, or the Bligh and Dyer procedure can be used as desired. The technique also works well in analyzing lipids bound to silica gel on an HPTLC plate—a unique property. The unique property of MALDI and a promising area for further development is that the technique can be used to look at lipid distribution in whole brain tissue preparations. This could be invaluable in assessing the efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy for lipid storage diseases for example.

The term MALDI (Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization) was coined by Hillenkamp and Karas and it has become a promising area for development to look at lipid distribution in whole brain preparations. This could be invaluable in assessing the efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy for lipid storage diseases. MALDI-TOF is the most common Proteomics Lab MS set-up, but also works well for measurement of brain lipids insitu, and can overcome problems of structural heterogeneity in the brain. It has benefitted from the development of new and improved matrix compounds. MALDI-MS measures the spatial distribution and relative abundance of target molecules. The matrix compound can be deposited on a lipid extract on the surface of a MALDI plate or directly on a frozen brain section mounted on a MALDI plate. The instrument functions in a high vacuum so MALDI matrix stability is important. A pulsed laser is then used to desorb and ionize the lipids, using the laser to build up a distribution pattern of the selected ion. Most commercial instruments operate in the UV at 337nm with the matrix (commonly DHB) in 100-100,000 excess. Intact analytes go into the vapor phase where H+ and Na+ ions are exchanged between matrix and analytes to yield a charged adduct [M+H]+ or [M+Na]+). Ions are then accelerated for TOF separation, low mass first. A Reflecton smoothes things out and sensitivity is around 30ppm. Most Labs include an HPLC separation to get rid of major lipid species such as PC and PE. Cholesterol is rarely measured this way because enzyme kits are well-developed but phospholipids such as PC are well-studied, as are related sphingomyelins, using an Sphingosylphosphorylcholine internal standard. The sensitivity (30-50ng) for SM is less than with PC. Lipids with a high negative charge (phosphatidic acid (P), lyso-PA and S1P) also show less sensitivity of detection and some special techniques such a making a Zn-complex may be required [30- 33].

3.11 Use of MALDI to Measure Glycolipids in specific brain regions

An important use of Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry is for the qualitative localization of lipid species in situ in brain sections, For gangliosides this means determining the structure of the attached oligosaccharide, the type of sialylation (eg: O- or N-acetylation), the chain length of the ceramide (C18:1 or C20:1) and the chain length of the fatty acid. Since imaging mass spectrometry can recognize both the oligosaccharide and the ceramide core a huge amount of data can be generated. As an example, “Molecular microscopy” [34] gives unique insights such as the distribution of gangliosides in the layers of the dentate gyrus where, the inner layer contains C18-gangliosides with C18-sphingosine whereas the outer layer contains C20;1 gangliosides. Embryonic brain gangliosides (GM3, GM2, GD3, and GD2) are mainly C18-ceramide and they are present in cell layers made up of the pyramidal cell layer and the granular layer of the dentate gyrus. In contrast, the major mature brain gangliosides (GM1, GD1a/b, and GT1a/b) and GQ1a/b/c are found in the substantia nigra, cerebral peduncle, hippocampus, and midbrain. At present we do not understand the significance of findings or others such as C20:1 sphingosine is enriched in the hippocampus and the substantia nigra, but MALDI offers the potential for structure-function studies to clarify these Mass-Spectrometers from the Synapt-G1/G2 family are widely employed for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI) of brain lipids. A lateral resolution of about 50 μm is typically achieved with these instruments, which is often, below the desired cellular resolution. However, MALDI-MSI can go down to about ten micrometers with a Synapt G2-S HDMS mass spectrometer without oversampling by using laser beam shaping, a 4:1 beam expander, a circular aperture for spatial mode filtering and by replacement of the default focusing lens. Using this approach Kettling et al [34] employed dithranol as an effective matrix for imaging of acidic mouse brain lipids such as sulfatides, gangliosides, and phosphatidylinositols in the negative ion mode. At the same time, the matrix enabled MS imaging of more basic brain lipids in the positive ion mode. Uniform matrix coatings with crystals having average dimensions between 0.5 and 3 μm were obtained by spraying a chloroform/methanol matrix of solubilized brain lipids. Increasing the cooling gas pressure in the MALDI ion source after adding an additional gas line was furthermore found to increase the ion abundances of labile lipids such as gangliosides. They demonstrated MALDI-MSI analysis of fine structures in coronal mouse brain slices [34].

4. Methods for measuring specific brain lipids

4.1. Measurement of Sphingosine-1-phosphate

The use of MS/MS, as described above, has allowed investigators to follow the effect of growth factors, cytokines and agonists in elevating S1P levels in brain. At least five high affinity G-protein coupled receptors exist for sphingosine–1-phosphate (SIP1-5R). Reduced S1P is often an indication of pathogenesis and this is seen in brain of patients with stroke and Multiple Sclerosis [26] and other common diseases [35]. More enigmatic is the acylated form ceramide-1-phosphate [36].

4.2. Measurement of Sphingoid storage disease lipids

Galactosylsphingosine (psychosine) can be detected in Krabbe disease brain [37], glucosylsphingosine in infantile Gaucher disease, brain, sulfogalactosylsphingosine (lysosulfatide) in metachromatic Leukodystrophy brain [38] and galactosyl-alpha-galactosylglucosylsphingosine in Fabry disease. They are of interest because they are disease-diagnostic in pathological brains and nerves whereas their unglycosylated forms (Sphingosine and dihydrosphingosine can be measured in normal brain and therefore perhaps have some function (Fig.10). Because of their diagnostic value, techniques have been developed for their analysis in brain and other tissues.

As an example lysosulfatide can be measured in normal human brain and may act as an extracellular signal to regulate the migration of neural precursor cell [38], promoting process retraction and cell rounding. Based on RT-PCR, Western blotting and immunocytochemistry, lysosulfatide appears to bind to the S1P3 receptor and 3 microM lysosulfatide produces a rapid increase of [Ca2+]. Although most lysosphingolipids activate calcium, lysosulfatide may play a specific pathogenic role in the demyelination associated with Metachromatic Leukodystrophy [38]. The related Sphingosylphosphorylcholine is another novel signaling molecule, which binds to a heptahelical receptor typified by GPR12 and has a similar calcium-mobilizing action. Once again we know of its existence only through MS/MS brain lipid analysis, which is the preferred way to measure these glycosylsphingosines. Similarly, HPLC/MS/MS analysis revealed the presence of another novel glycolipid, glyceroplasmalopsychosine in bovine brain, but again the function of this and other trace galactolipids in brain remains essentially unknown [39].

4.3 Measurement of ceramide by diacylglycerol kinase assay

Because of the role of ceramide in activating an Akt-phosphate phosphatase to initiate the apoptotic cascade in brain, considerable effort has been to measure ceramide levels in brain and other tissues. In addition to MS/MS approaches already described, ceramide levels can be measured based on the use of bacterial diacylglycerol kinase to convert ceramide to ceramide-l-[32P]phosphate [40]. Lipids are extracted from brain tissue as described earlier and the dried lower phase is dissolved in 7.5% n-octyl-~-glucopyranoside, 5 mM cardiolipin, and 1 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid solution by heating to 70°C, followed by sonication and vortex-mixing. The lipid extract is then incubated with 50 pg/ml of diacylglycerol kinase, and 1 mM [y-32P]ATP (5pCi) for 30 min in MgCl2/DTT/EGTA pH 7.4 imidazole buffer. Lipids are re-extracted and spotted on HPTLC plates and developed in Chloroform-acetone-methanol-acetic acid 10-4-3-2-1 v/v [41]. Cer-1-Phosphate standards indicate the area to be scraped for liquid scintillation counting and this can be confirmed by autoradiography.

4.4 Measurement of Dihydrosphingolipids

It has recently been shown by lipid analysis that restricting oxygen to the brain leads to inhibition of dihydroceramide desaturase and the accumulation of dihydroceramides, dihydrosphingomyelins and dihydroglycosylceramides [42,43]. DHC is also seen in Hemorrhagic stroke [37] and this evidence of hypoxic injury to brain and can be detected by both HPTLC and HPLC/MS/MS (Fig.13). They have a separate metabolic pathway from the more bioactive ceramides and S1P (Fig 13]) [42,43] and in fact little is known of the biological function of dihydrosphingosines. A myco-toxin found in corn (Fumonisin B1) inhibits de novo synthesis of sphingolipids and leads to increases in dihydrosphingosine and deoxysphingolipids, which may be responsible for some of the brain-specific brain structural deficits observed in different animals.

Fig 13.

Different metabolic fates of exogenous C6-ceramide (diagonal bars) and C6- dihydroceramide (open bars) in neonatal rat hippocampal neuron cultures as described in [26]. Quantification was done by HPLC/MS/MS.

4.5 Measurement of Deoxysphingolipids

Mutations in the Serine-Palmitoyltransferase gene, can lead to hereditary sensory neuropathy Type 1 (HSAN1)[44] from the formation of deoxysphingolipids by using alanine instead of serine. The chemical footprint (deoxysphingolipid) was revealed by MS/MS analysis. The fact that this mutation causes defects in peripheral neurons not in central neurons suggests that de novo synthesis is less important in brain than peripheral nerve and that sphingolipids are either recycled efficiently or derived from sphingomyelin in the diet. In HSAN1A the mutated SPT produces both 1-deoxysphinganine and 1-desoxymethylsphinganine. This is because the HSAN1-associated mutant SPT has a reduced preference for L-serine and an increased activity toward amino acids (mainly, alanine and glycine). Oral administration of L-serine reduces the formation of 1-deoxy sphingolipids in mice and humans with HSAN1 and potentially could help patients with diabetic neuropathy.

4.6. Measurement of Cholesterolglucoside and Phosphatidylglucoside

Cholesteryl glucoside (β-ChlGlc), a monoglucosylated derivative of cholesterol, has recently been measured in brain and is involved in activation of heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1) leading to the expression of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70). Intriguingly, overexpression of β-glucosidase 1 (GBA1, lysosomal acid β-glucocerebrosidase) led to an increase in cholesterol glucosylation whereas in type 2 Gaucher disease patients with severe defects in GBA1 activity, cholesterol glucosylation activity was very low. GlcCer containing mono-unsaturated fatty acid was the more-preferred substrate for cholesterol transglucosylation when compared with GlcCer containing same chain length of saturated fatty acid. [45]. Thus GBA1 can also function as a β-ChlGlc-synthesizing enzyme.

Brain has also been shown to contain Phosphatidylglucoside (PtdGlc)[46] A combination of Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis and GLC- mass spectroscopy indicated that the chemical structure of PtdGlc in fetal rat brain was 1-stearyl-2-arachidoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphoryl-β-D-glucopyranoside, together with acetylated PtdGlc, 1-stearyl-2-arachidoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphoryl-β-D-(6-O-acetyl)glucopyranoside. [46]. The PtdGlc isolated from fetal rat brain was almost uniquely homogeneous and very few other brain lipids have the C20:0 acyl chain as a major component. In addition, PtdGlc from rat brain contained a stereoisomer, 1-sn-phosphatidylglucoside [46]. Thus brain lipidomics promises continuing surprises in the future.

4.7. Measurement of Sphingomyelin with Lysenin

Lysenin, is a novel 41-kDa protein purified from the coelomic fluid of the earthworm Eisenia foetida, which binds specifically to sphingomyelin [47] and can be used to measure sphingomyelin in brain. Preincubation of lysenin with vesicles containing sphingomyelin incompletely inhibits lysenin-induced hemolysis whereas vesicles containing phospholipids other than sphingomyelin do not, suggesting that lysenin binds specifically to sphingomyelin on membranes. The specific binding of lysenin to sphingomyelin was confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, TLC immunostaining, and liposome lysis assay. In these assays, lysenin bound specifically to sphingomyelin and did not show any cross-reaction with other phospholipids including sphingomyelin analogs such as sphingosine, ceramide, and sphingosylphosphorylcholine.

4.8. Use of toxins to measure sphingolipids: Cholera toxin for GM1 and veratoxin for GbOse3Cer

These lipids can be used in ELISA assay or histochemical analysis of brain followed by quantification using Image-J software [48]. Fatty acid heterogeneity has been clearly shown to regulate the binding of toxins such as veratoxin to neutral glycolipids (GbOse3cer) [49] so studies should include fatty acid analyses by GLC or MS/MS.

4.9. HPTLC and detection/quantification by antibody

Since monoclonal antibodies are now available to detect most glycolipids HPTLC-antibody technology has been useful in detecting pathological lipids normally present in very small amounts in brain. Thus many antibodies specific for different glycolipids can be used to detect and quantify glycolipids following chromatography on HPTLC [50] or be measured semi-quantitatively by immunocytochemistry of brain sections.

4.10 Measurement of Lactoneotetraose glycolipids and the HNK antigen

MS/MS can be used to detect a complex group of neolacto-glycolipids (LcOse4Cer and LcOse6Cer) in cortex and cerebellum and their developmental profile suggests that they are important in the embryonic development of the brain. They consist of fucosyl, sialosyl-, disialosyl- and O-acetyldisialosyl- forms and while embryonically enriched in embryonic purkinje cells, they are all absent from postnatal brain. In addition, sulfuronyl carbohydrate can be linked to Lcose4cer and LcOse6cer (as well as to glycoproteins and proteoglycans) to form the HNK antigen. This is highly immunogenic and elevation of anti-HNK antibodies can lead to a peripheral neuropathy. These brain sphingolipids (often termed SGGLs) have been implicated in migration of neural crest cells, adhesion and as promoters of neurite outgrowth in motor neurons so a number of techniques have been developed to quantify them [51].

Over 60 years of intensive analytical study has yielded a huge amount of information about gangliosides (sialoglycosphingolipids) and their enrichment in brain. Analysis by HPTLC is still common since HPLC/MS/MS of the minor species is still challenging because of the lack of authentic samples for quantitation. In addition to the major classes of ganglioside, further sub-families can be generated in vivo by enzymatic modification of the terminal sialic acids, for example 9-O-acetylation (as detected with the Jones antibody). This process may be required to co-ordinate growth cone mobility and axonal branch formation in the CNS. Conversion of N-acetyl- to N-glycolyl- neuraminic acids creates a further sub-set of gangliosides common in non-human animals, but is readily detected by MS/MS and as yet has no known specific function in brain, except that there could be immunological consequences, if, for instance, pluripotential stem cells are grown in fetal calf serum prior to differentiation into brain cells.

MS/MS has been used to show that neuroectodermic tumors typically express novel glycosphingolipid antigens on their surface. These can be shed and act as immunosupressors of cytotoxic t-cells and dendritic cells [52]. Attempts have been made to implicate glycosphingolipids, especially fetally expressed species, in the high metastatic potential of malignant gliomas. Thus astrocytomas are typically enriched in paragloboside whereas oligodendroglial tumors are enriched in asialo-GM1 (GA1) and Galactosylceramide (or at least high levels of UDP-galactose: ceramide galactosyltransferase activity). Brain tumors are also frequently enriched in GM2 and GD3, gangliosides which occur in mature brain in only trace amounts. Thus identifying glycolipid oncofetal antigens may have diagnostic importance for brain tumors and could be the target of cancer immunotherapy.

4.11 Measurement of Glucosaminylphosphoinositide (GPI) anchored proteins

GPI-anchored proteins associate with lipid microdomains [55]. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol is attached to the C-terminus of certain brain proteins (such as OMG) during posttranslational modification. The phosphatidylinositol fatty acid membrane anchor attaches glucosamine and mannose residues to an ethanolamine phosphate and then to the C-terminal amino acid of a mature protein. Glycerophosphocholine choline phosphodiesterase (GPC-Cpde) is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored alkaline hydrolase that is expressed in oligodendrocytes and found in the myelin sheath.Cleavage of the group by a PI-specific phospholipase C results in release of the protein from the membrane and this can be quantified by QTOF MS/MS fragment analysis (64). Excised gel pieces can be reduced, alkylated and digested in situ with 6 ng/μl trypsin (V511A, Promega) and the peptide mixtures containing 1 % formic acid loaded onto a TMUltra Performance Liquid Chromatograph. Following separation of peptides with a gradient of 5–90 % acetonitrile, 0.1 % formic acid, they can be eluted to a Q-TOF Ultima Global mass spectrometer and subjected to data-dependent tandem mass spectrometry analysis, selecting Peptides with 2+ and 3+ charges for MS/MS. Peak lists generated by the ProteinLynx Global server software (version 2.1), and the resulting pkl files are then searched against the Swiss-Prot 56.8 protein sequence data bases using MASCOT search engine (http://www.matrixscience.com/).

Soluble GPC-Cpde from bovine brain had an amino acid sequence identical to ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 6 (eNPP6) precursor (64), but lacks the N-terminal signal peptide region and a C-terminal region, suggesting that the hydrolase was solubilised by C-terminal proteolysis to releasing the GPI-anchor. sGPC-Cpde was found to be specific for lysosphingomyelin rather than GPC or lysophosphatidylcholine, suggesting that GPC-Cpde may function mainly in sphingolipid signaling, rather than in the homeostasis of acylglycerophosphocholine metabolites. The truncated high mannose and bisected hybrid type glycans found in sGPC-Cpde are typical of the glycans in lysosomal glycoproteins, which undergo GlcNAc-1-phosphorylation as they pass through the Golgi. Thus, sGPC-Cpde may originate from lysosomes and possibly regulate mGPC-Cpde on the myelin membrane and therefore influence brain lipid composition. Although outside the scope of this review, posttranslational modifications of proteins by lipids such as palmitate, myristate and farnesyl can be measured by similar MALDI-TOF or QTOF approaches and help increase our understanding of lipid dynamics in the nervous system.

4.12. Measuring brain lipids with antibodies in ALS-like disease

Autoantibodies to gangliosides have been detected in patients with symptoms of motor neuron disease and this is the only treatable form of motor neuron disease since immunosupressors such as cytoxan are usually effective. Many years of laboratory testing in peripheral nerve disease suggests that antibody assays are very selective and can be used to quantify normally minor gangliosides as well as quantification of GM1, Asialo-GM1 (Anti-GA1), GD1a, GD1b, GQ1b, MAG-SGPG, Sulfatide) [53, 54]. The gangliosides most commonly recognized by neuropathy associated autoantibodies are GM1, asialo-GM1, GD1a, GD1b, and GQ1b. Detection of ganglioside M1 (GM1) antibody, usually of the IgM isotype, is associated with multi-focal motor neuropathy and lower motor neuropathy, characterized by muscle weakness and atrophy, in approximately 50 % of persons with multi-focal motor neuropathy. GM1 antibodies of the IgG and IgA isotypes may be found in association with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) 53-55). It should be noted that cholera toxin can also be used to quantify GM1. Ganglioside glycolipid antibodies may also be associated with different forms or aspects of Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS). Thus increased titers of IgG anti-GM1 or GD1a ganglioside antibodies have been associated with GBS and acute motor axonal neuropathy and antibodies to GM1 and GD1a are mostly associated with axonal variants of GBS. Antibodies to GT1a are associated with swallowing dysfunction. Antibodies to GD1b are associated with pure sensory GBS. Increased IgG anti-GQ1b ganglioside antibodies are closely associated with the Miller-Fisher syndrome, antibodies against GQ1b are found in 85 to 90 % of patients with the Miller Fisher syndrome, characterized by ataxia, areflexia, and ophthalmoplegia. GQ1b antibodies are also found in GBS patients with ophthalmoplegia, but not in GBS patients without ophthalmoplegia. Antibodies to GQ1b may also be present in Bickerstaff encephalitis and the pharyngocervical brachial GBS variant, but not in disorders other than GBS.

Some individuals with proximal lower motor neuron syndromes (P-LMN) (30 %) have selective serum antibody binding to asialo-GM1 ganglioside; however, there is no evidence that P-LMN syndromes respond to the immunosuppressive treatment that has been somew hat successful in treating these ALS-like diseases (53, 54).

Most glycolipids are firmly attached to membrane microdomains (an exception being the “shedding” observed in cancer cells) [52] the reactivity of the GSL sugars with binding proteins and antibodies has been used to measure their concentration. However the binding does appear to be somewhat dependent upon the fatty acid composition. Most glycolipids show extensive fatty acid heterogeneity (C16-24) with highly antigenic lipids such as galactosylceramides and sulfatides containing a wide range of fatty acids, about 50% of which are alpha-hydroxylated and/or monounsaturated. This affects their reactivity, because it affects their mobility in microdomains but is less of a problem with brain gangliosides since they are almost exclusively C18:0 fatty acids with a mixture of C18 and C20 sphingoid bases. Gangliosides are very minor components of non-neural tissue and when they do occur, typically in cancerous cells, they show fatty acid heterogeneity typical of non-CNS glycolipids.

4.13 Measurement of lyso-PAF

Age related macular degeneration has been associated with platelet-activating factor (PAF) and lyso-PAF and LC/MS/MS techniques can be used to quantify the levels and document attempts to reduce PAF in the nervous system (56). Anti-personel agents such as the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor pyridostigmine bromide (PB) and the pesticide permethrin (PER) induced cognitive impairment and anxiety and increased gliosis which was associated with reduced lyso-PAF levels upon MS analysis. In contrast, levels of Phosphatidylcholine (PC), plasmalogen ether PC (ePC) and Sphingomyelin were all elevated in the brains of the exposed mice. Since lyso-platelet activating factors (lyso-PAF) are products of ePC (56), measuring their levels suggested that these agents cause peroxisomal and lysosomal dysfunction in the brain.

5. Future developments in brain lipid measurement

5.1. Measurement of non-physiological cell-penetrating lipids in brain following attachment to intensely fluorescent Quantum dots

Improving Mass-spectrometry technology offers the promise of being able to identify and quantify lipids in smaller samples of brain, eventually reaching the single cell level and showing that different lipidspecies have different roles in specified areas of brain and different subcellular compartments [57-59]. Since the brain is a lipophilic organ we should eventually be able to deliver lipids or lipid-digesting enzymes to specific brain regions. The problem at the moment is the blood-brain barrier but this could be overcome by designing a synthetic lipid which would stably fluoresce or which could be attached to a fluorescent entity and which would function as a cell membrane-penetrating lipopeptide such as JB577 (61-63). This might overcome the problem of delivering therapeutics to neurons and we can follow their success by lipidomics.

The blood brain barrier can be breached by viruses and bacteria

We have learned from studying viruses and bacteria, and from many failed attempts to get proteins into brain that only peptides enriched in positively charged amino acids (Arg and Lys) (such as the Tat protein of HIV) are able to penetrate the blood brain barrier [60].

Structure of cell-penetrating peptides compared to JB577

We therefore need methods to specifically attach lipid cargos to the carrier so that they can be delivered to specific brain cells where injury has occurred and we have a method of measuring recovery of normal brain lipids. This can be done by using CdSe/ZnS Quantum dots which have been solubilized by a specific coating and attached to a His6-lipo-peptide through the surface zinc molecules (61-63). To evaluate success (delivery of lipopeptide cargo to neurons rather than glia) we need a method of tracking the delivery vehicle, the cargo and the visualization of the target. Some Nanoparticles such as Quantum dots offer the possibility of achieving these goals. Typically nanoparticles have been liposomes, gold particles or magnetic particles but CdSe/ZnS Quantum Dots offer many advantages over these other particles [61, 62] in terms of stability, intrinsic high fluorescence and the ability to put a coating on the Quantum Dot (QD) which makes them both soluble and surface active (positive charged, negatively charged or neutral depending on the brain cell target you have selected). Negative charge works for delivering cargo to neurons( 62). The Zn on the surface of the QD can be used to bind cargo by attaching polyhistidine (HIS6) to the C or N-terminal end of the peptide/protein/drug. This binding is quite tight (72h in cultured cells, longer in brain) and QDs can release the cargo in vivo over a period of >15 days in chick brains [63]. The incorporation of a cell-penetrating peptide (JB577) (WGDapVKIKK), a non-hydrolysable analog of palmitoylated K-Ras 4A, into the construct allows release of the cargo from the endosome (a huge problem for other types of drug/protein delivery) and potentially promotes penetration of the blood brain barrier of the therapeutic you are trying to deliver (61). Thus by mixing coated QDs, His-JB577 and HIS-enzyme or His-DRUG in different proportions we can optimize the conditions for delivery to the brain and follow the fate of the lipid cargo in brain (Fig.14).

Fig. 14.

Exogenously added lipids and lipopeptides can be measured in brain tissue after delivery attached to Coated Quantum dots. The amount of lipid delivered to the brain can be quantified by image J/Fuji software (NIH). Panel A: Low resolution image of part of the Ventricle of a 6 day old chick embryo, 2 days after injection of QDs with a CL4 coating and a lipopeptide cargo (His6-G2-Pro9WG[palmitoyl]DapVKIKK) (JB577) into Day 4 embryonic spinal column. The uniform distribution of QD-CL4s into neuroblasts can be readily seen and this persists until day 11 when the QDs are concentrates in the developing choroid plexus and start to disappear from the brain.

Panel B: Addition of the same lipopeptide to a neonatal rat hippocampal slice preparation (62) showing preferential labeling of Pyramidal neurons and essentially no labeling of glial cells. Red is QDs, blue is DAPI nuclear staining and green is Nissl body staining for neurons. The amount of lipid introduced into the brain tissue can be measured by Fuji software in an unbiased manner.

Animal models (mice and zebra fish) exist for many human diseases and by microinjecting 2 day old zebrafish larvae we can follow the fate of the QDs in living fish and monitor the efficiency of replacement of growth factors/mutant protein by normal protein. The minute amounts of QD involved results in no toxicity that we can detect and the power of the QD is the ease with which we can follow their fate. The particles are also electron-dense enough that we can use electron microscopy to determine subcellular localization (62,63). A major problem with current therapies is that microglia (or macrophages) are likely to sequester a major portion of any cargo but we can prevent this by using zwitterionic or negatively charged coats (CL4) to specifically target the cargo (enzyme) to neurons rather than glia [63]. We have also discovered that by digesting away the extracellular matrix surrounding glial cells we can promote uptake by oligodendrocytes and hopefully induce remyelination.

We look forward to more exciting advances in measuring brain lipids (for example: 65-67), which will hopefully result in better appreciation of the role of these enigmatic molecules in brain function and dysfunction.

Highlights.

A review that covers isolation, identification and quantification of brain lipids.

Covers chromatography, immunoassay, isotope, enzyme assay and mass-spectrometry.

Provides references for isolating and measuring almost any brain lipid.

Table 1.

Structure of cell-penetrating peptides compared to JB577

| PEPTIDE | AMINO ACID SEQUENCE |

|---|---|

| JB577 | WGDap[Palmitoyl]VKiKK |

| Penetratin | RQJKIWFQNRRMKWKK |

| Tat49-57 | RKKRRQRRR |

| Transportan | GKINLKALAALAKKIL |

Acknowledgements

My interest in brain lipids has been sustained by the continuous support of NIH for over 40 years (NS36866 and HD09402). The work summarized in this Chapter is based on over 70,000 research papers and the work of many excellent researchers and colleagues. If their work has not been referenced it in no way diminishes their contributions to this amazing body of research carried out on brain lipids. Specific thanks go to the late Charles C. Sweeley for inducing me to cross the Atlantic and learn about Mass-Spectrometry and Glycolipids and to the University of Chicago for providing excellent colleagues and facilities. Finally I would like to thank John P Kilkus for many lipid analyses, Sylvia Dawson for help with the artwork and general layout of the review, Ryan Walters, Fernando Testai and Jingdong Qin. Detailed discussion of structures of the lipids discussed can be found in the LIPID MAPS website.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement: All third-party financial support for the work in the submitted manuscript has been from USPHS Grants NS-36866-40 and HD-09402 together with the University of Chicago.

There are no financial relationships with any entities that could be viewed as relevant to the general area of the submitted manuscript.

There are no sources of revenue with relevance to the submitted work who made payments to you, or to your institution on your behalf, in the 36 months prior to submission.

There are no other interactions with the sponsor of outside of the submitted work .

There are no relevant patents or copyrights (planned, pending, or issued).

There are no other relationships or affiliations that may be perceived by readers to have influenced, or give the appearance of potentially influencing, what you wrote in the submitted work.

References cited

- 1.Rouser G, Kritchevsky G, Galli C, Yamamoto A, Knudson AG., Jr. In: Variations in lipid composition of human brain during development and in the Sphingolipidoses: use of two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography. Aronson SM, Volk BW, editors. Pergamon Press; New York: 1967. pp. 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ledeen R, Salsman K, Gonatas J, Taghavy A. Structure comparison of the major monosialogangliosides from brains of normal human, gargoylism, and late infantile systemic lipidosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1965;24:341–345. doi: 10.1097/00005072-196504000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huwiler A, Kolter T, Pfeilklschifter J, Sandhoff K. Physiology and pathophysiology of sphingolipid metabolism and signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1485:63–99. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane-Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bligh E, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svennerholm L, Fredman P. A procedure for the quantitative isolation of brain gangliosides Biochim. Biphys. Acta. 1980;617:97–107. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(80)90227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cochran FB, Jr, Yu RK, Ledeen RW. Myelin gangliosides in vertebrates. J Neurochem. 1982;282:773–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb07959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakomori S-I. Structure and function of glycosphingolipids and sphingolipids:recollections and future trends. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:325–346. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirabayashi Y. A world of sphingolipids and glycolipids in the brain —Novel functions of simple lipids modified with glucose—. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2012;88:129–143. doi: 10.2183/pjab.88.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hawthorne JN, Kemp P. The brain phosphoinositides. Adv Lipid Res. 1964;2:127–166. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4831-9938-2.50010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel-Latif AA, Chang FE. Separation and quantitative determination of 32P-labelled lipids from brain particulates by thin-layer chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1966;24:435–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)98186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tajima Y, Ishikawa M, Maekawa K, Murayama M, Senoo Y, Nishimaki-Mogami T, Nakanishi H, Ikeda K, Arita M, Taguchi R, Okuno A, Mikawa R, Niida S, Takikawa O, Saito Y. Lipidomic analysis of brain tissues and plasma in a mouse model expressing mutated human amyloid precursor protein/tau for Alzheimer’s disease. Lipids in Health and Disease. 2013 doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-12-68. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-12-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall NA, Patrick AD. Accumulation of Dolichol-linked Oligosaccharides in Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (Batten Disease). Amer j. Med. Genetics Suppl. 1988;5:221–232. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320310625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.JS Schaik, Miller TM, Graham SH, Manole MD, SM Rapid and simultaneous quantitation of prostanoids by UPLC-MS/MS in rat brain. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2014;945-946:207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simons K, Gruenberg J. Jamming the endosomal system: lipid rafts and lysosomal storage diseases. Cell Biol. 2000;10:459–463. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckert G, P., Igbavboa U, Muller WE, Wood WG. Lipid rafts of purified mouse brain synaptosomes prepared with or without detergent reveal different lipid and protein domains. Brain Res. 2003;962:144–150. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03986-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson G, Fuller M, Helmsley KM, Hopwood JJ. Abnormal gangliosides are localized in lipid rafts in Sanfilippo (MPS3a) mouse brain. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:1372–80. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0761-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs B, Süss R, Teuber K, Eibisch M, Schiller J. Lipid analysis by thin-layer chromatography: a review of the current state. Journal of Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218:2754–2774. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banerjee P, Dasgupta A, Chromy B, Dawson G. Differential solubilization of membrane lipids by detergents: Co-enrichment of the sheep brain serotonin 5HT1A receptor with phospholipids containing predominantly saturated fatty acids Arch Biochem. Biophys. 1993;305:68–77. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee P, Dasgupta A, Siakotos AN, Dawson G. Evidence for lipase abnormality: high levels of free and triacylglycerol forms of unsaturated fatty acids in neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis tissue. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:549–554. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCluer RH, Ullman MD, Jungalwala FB. High-performance liquid chromatography of membrane lipids. Glycosphingolipids and Phospholipids in Methods in Enzymology. Biomembranes Part 5. 1989;172:538–575. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(89)72033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takemoto Y, Suzuki Y, Horibe R, Shimozawa N, Wanders RJ, Kondo N. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis of very long chain fatty acids, docosahexaenoic acid, phytanic acid and plasmalogen for the screening of peroxisomal disorders. Brain Dev. 2003;25:481–487. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(03)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dawson G, Sweeley CC. In vivo studies on glycosphingolipid metabolism in porcine blood. J Biol Chem. 1970;245(2):410–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawson G, Sweeley CC. Mass spectrometry of neutral, mono- and disialoglycosphingolipids. J Lipid Res. 1971;12:56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hein LK, Duplock S, Hopwood JJ, Fuller M. Lipid composition of microdomains is altered in a cell model of Gaucher disease. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1725–1734. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800092-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin J, Berdyshev E, Goya J, Natarajan V, Dawson G. Neurons and oligodendrocytes recycle sphingosine-1-phosphate to ceramide; significance for apoptosis and multiple sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14134–14143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng H, Guan S, Han X. Abundance of triacylglycerols in ganglia and their depletion in diabetic mice: Implications for the role of altered triacylglycerols in diabetic neuropathy. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:1288–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03794.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han X, Gross RW. Shotgun lipidomics: Electrospray ionization mass spectroscopic analysis and quantitation of the cellular lipidomes directly from crude extracts of biological samples. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2005a;24:367–412. doi: 10.1002/mas.20023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]