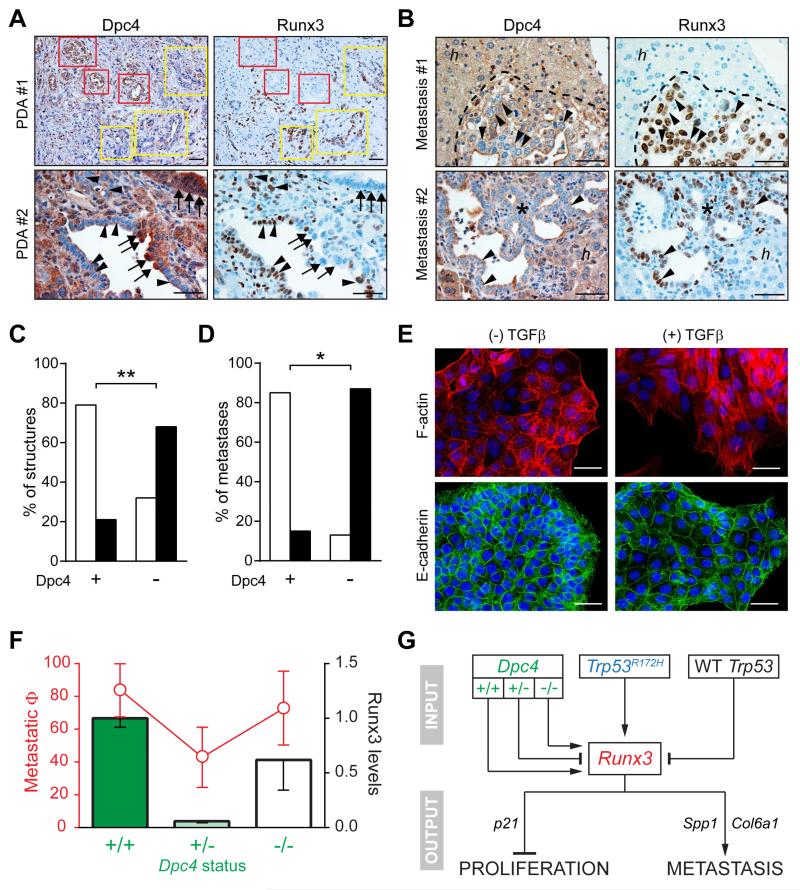

Figure 6. Dpc4 and Runx3 coordinately regulate metastatic behavior in PDA.

(A) Spontaneous focal loss of Dpc4 (left) in representative autochthonous KPDC PDA correlates with acquired Runx3 expression (right). Yellow boxes and arrowheads indicate areas of focal Dpc4 loss and acquired Runx3 expression in tumor epithelia; red boxes and arrows indicate regions of Dpc4 retention and undetectable Runx3.

(B) Liver metastases (asterisks and dotted outlines) from KPDC mice reveal spontaneous loss of Dpc4 and corresponding increases in Runx3 expression (arrowheads). Note that hepatocytes (h) retain Dpc4 and do not express Runx3.

(C and D) Quantification of Dpc4 and Runx3 IHC in (C) glandular structures in primary KPDC tumors and (D) liver metastases from KPDC mice. Runx3-low structures/metastases are represented by open bars and Runx3-high by black bars. Fisher’s exact test revealed a significant correlation between Dpc4 loss and Runx3 expression (**p<0.0005, *p<0.005).

(E) Immunofluorescence of actin stress fibers (upper panels) and surface E-cadherin (lower panels) in KPDDC cells ±TGFβ. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue).

(F) Metastatic potential (Φ) plotted as fraction of mice exhibiting metastases (red, ± 95% confidence interval) and relative Runx3 protein levels (black outlined bars; mean ± SEM) as a function of Dpc4 status (green).

(G) Model for the regulation and role of Runx3 in proliferation and metastasis of PDA. Runx3 levels are influenced by Dpc4 status in a biphasic manner and increase only after LOH of Trp53 in the context of point-mutant Trp53. Runx3 expression in turn stimulates synthesis and secretion of proteins that promote migration and metastatic niche preparation, while simultaneously inhibiting proliferation.

Scale bars, 50 μm. See also Figure S5.