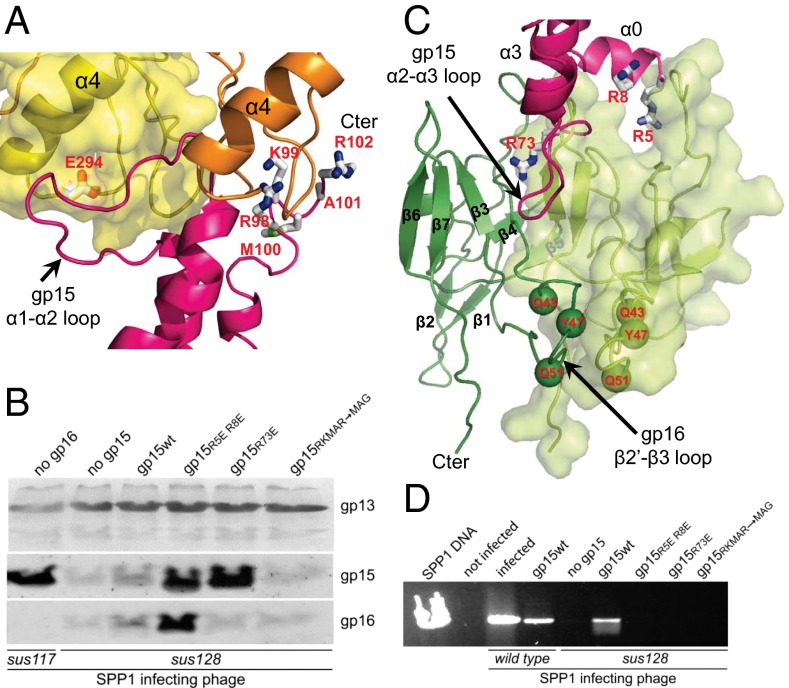

Fig. 3.

Gp15 interaction with gp6 and gp16. (A) Interface of two subunits of gp6 (ribbons in orange and surface representation in yellow) with one gp15 subunit (magenta) in HTIFull. The gp15 subunit is viewed from outside the complex and is rotated slightly clockwise. Side chains of gp6 and gp15 residues which when mutated prevent the gp6–gp15 interaction are displayed as sticks and are labeled in red. (B) Composition of purified capsids assembled in bacteria producing different mutant versions of gp15 as labeled above each gel lane and infected with the gp15-defective phage SPP1sus128. Capsids produced during infection with the gp16-defective mutant SPP1sus117 are a control (far left lane) showing that gp15 incorporation at the portal vertex precedes gp16 binding (4, 21). Gp13, the major capsid protein, gp15, and gp16 were detected by Western blot. Note that infection of the strain producing wild-type gp15 by SPP1sus128 leads to complementation, yielding complete virions that do not copurify with capsids. In such cases tailless capsids carrying gp15 and gp16 are present in reduced amounts (lane gp15wt). (C) Interface of gp15 subunit (magenta) with two subunits of gp16 (ribbons in green and surface representation in light green) of HTIFull. Gp15 residues which when mutated disrupt assembly are displayed as in A. Gp16 residues mutated to cysteine (Figs. 5 and 6) are shown as green spheres. (D) DNA protected from DNase inside viral particles assembled in the presence of different gp15 mutant proteins, as labeled above each gel lane. The assay was carried out in crude lysates of cells infected with wild-type SPP1 and SPP1sus128 as marked below the gel. Purified SPP1 DNA (far left lane) was used as control.