Key messages

Effective public health/primary care partnerships require practitioners from both sides to span the intellectual and practical boundaries that separate them.

Boundary spanning can involve risk when working across seemingly safe or comfortable and institutionalised limits.

This risk can be reduced by mechanisms that enable and support creative interaction between people from both (all) sides of the relevant boundaries.

Collaborative innovations that have potential to improve the health of whole people and whole communities can emerge from cross-boundary creative interactions.

Health services need high-level skills at boundary spanning, including systems-thinking practitioners and managers, and mechanisms that support it, including relationship-building between disciplines and organisations through shared projects.

Why this matters to us

The authors' personal experience is that boundary-spanning thoughts and actions are among the most meaningful and potentially impactful activities to improve health. We also experience that boundary-spanning work is likely to be unsupported, maligned or beaten down by entrenched entities. Therefore, we are working on Promoting Health Across Boundaries (PHAB) in order to develop, share and apply new knowledge about the connections that foster health. This initiative is a developmental process that involves: defining the role of boundary spanning; discovering individuals and organisations that are already engaged in promoting health across boundaries; developing collaborations, research and shared learning initiatives that aim to promote health; and eventually, delivering improved health for individuals and communities through boundary-spanning initiatives and programmes.

This article includes early insights from a diverse and evolving group interested in promoting health across boundaries. This group explicitly represents multiple disciplines both within and outside the fields of health and health care. Currently, it is shaded toward one locality (Cleveland, Ohio and Case Western Reserve University in the USA), but is growing to include experience from diverse locales. We hope that this article will stimulate readers to share their own experiences and knowledge on the PHAB website (www.phab.us) to further the process of Defining and Discovering that will lead to Developing collaborative learning and Delivering improved health through boundary-spanning initiatives.

Keywords: boundary spanning, collaboration, innovation, systems thinking

Abstract

Boundaries, which are essential for the healthy functioning of individuals and organisations, can become problematic when they limit creative thought and action. In this article, we present a framework for promoting health across boundaries and summarise preliminary insights from experience, conversations and reflection on how the process of boundary spanning may affect health. Boundary spanning requires specific individual qualities and skills. It can be facilitated or thwarted by organisational context. Boundary spanning often involves risk, but may reap abundant rewards. Boundary spanning is necessary to optimise health and health care. Exploring the process, the landscape and resources that enable boundary spanning may yield new opportunities for advancing health. We invite boundary spanners to join in a learning community to advance understanding and health.

This moment in time

Around the world, growing fragmentation of health care and demographic and social changes are leading to unsustainable cost increases, inequalities and limited effectiveness in advancing the health of people and populations.1

General practitioner (GP) commissioning2,3 in the UK, like the Patient-Centered Medical Home4–9 and Accountable Care Organization10–13 movements in the USA, present opportunities to unite on-the-ground general practice (primary care) and high-level public health perspectives to promote health. In order to span the boundary between these two complementary approaches to health promotion, it is essential to have a shared vision for health that is bigger than either picture envisions on its own.

But boundary spanning is not easy.

To understand the difficulties of boundary spanning we conducted meetings and discussions with university faculty and community leaders across multiple disciplines who believe in the value of boundary spanning and its potential for enhancing health. In this article, we summarise some of these ideas generated from this forum and invite readers of LJPC to join future conversations to better understand how policy can stimulate boundary spanning to produce highly valued approaches to health promotion.

Boundary spanning and health

The combination of broad and grounded viewpoints that are needed for effective healthcare commissioning require moving beyond health care to focus on the goal of sustainably promoting health. Among diverse definitions,15–20 a concept is emerging of health as a resource to support important work and connection – the ability to develop meaningful relationships and pursue a transcendent purpose in a finite life.19 Focusing on a broad definition of health (www.phab.us/about/what-is-health), rather than solely on health care, converges attention on the social, environmental, organisational and relationship factors determining well-being, function, community and potential.

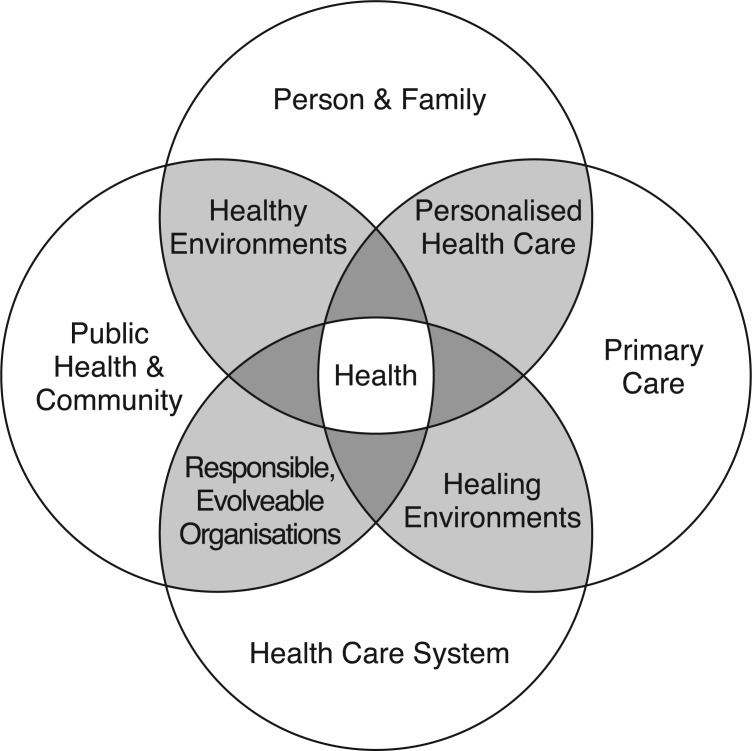

The model generated by the Promoting Health Across Boundaries (PHAB) initiative (Figure 1) depicts four related domains that affect health: (1) person and family,21,22 (2) primary care,23–26 (3) the healthcare system,12,27–29 and (4) public health and community.30–34 Figure 1 also names interfaces between these domains that are important to span to foster health. These interfaces relate to:

personalised health care

healing environments

responsible, evolvable organisations

healthy environments.

Figure 1.

Promoting health across boundaries

The interface between primary care and public health is particularly important to keep individuals and communities healthy. Primary care tends to focus on the disease treatment and health promotion needs of the individual with a limited view of all community members. Conversely, public health tends to focus on the health of whole communities and populations (including environmental health and health promotion campaigns) and can too easily lose sight of the individual. Partnership work requires mechanisms that permit creative interaction across the boundary between those with a personal focus and those with a population focus.

The case below (Box 1) shows an example of an ongoing boundary-spanning initiative.

Box 1. An example of boundary spanning between primary care and public health.

In the city of Cleveland, Ohio, patients of a primary care practice complained that their housebound elderly family members were not receiving personal health care. Data from the public health system confirmed that many of these people lived in a large impoverished neighbourhood and were hospitalised frequently through the emergency department for problems that could have been solved by personal care.

Using grants from local foundations, the practice piloted a housecalls programme (novel for the USA but familiar in the UK) to bring a primary care physician to the patient's home. This programme was successful, as perceived by the housebound patients involved. Consequently, the practice hired nurse practitioners to expand the programme.

The nurse practitioners and physicians discovered health-related needs that went beyond medical needs, including home safety, social isolation and health promotion, and are now exploring ways to meet these needs. Unlike the UK, in the USA there are few ways to support preventive or social and environmental determinants of health. One success achieved so far has been to team up with a government housing programme to fix leaking roofs and build entry ramps. The housecalls programme is now teaming up with a university initiative to bring broadband Internet to neighbourhoods and is seeking funding to use the Internet to expand home monitoring and healthcare communication for the frail elderly and to support a neighbourhood health promotion initiative for safety, healthy food and physical activity.

Community and business leaders in an adjacent community, hearing of the success of this initiative, raised philanthropic support to develop a similar housecalls programme for housebound elderly people in their neighbourhood. The practice is partnering with their local university to evaluate the effect of both programmes' outcomes on emergency department visits, hospitalisations and on the perceptions of patients and families on the degree to which their needs for personalised health care are being met.

The first boundary that was spanned in this initiative was between primary care and informatics (patient complaints and data of unnecessary hospitalisation). Later boundaries spanned were between primary care and housing and the university and business and technology sectors.

The programme had inherent risk. Initially, administrators felt that sending physicians into homes would be more costly and that it was, in turn, ‘going backwards’ in how to provide primary care. It was not certain that informatics, housing and business would contribute their resources, creating anxiety that primary care would become overwhelmed. Even now, the sustainability of funding for the parts of the initiative that go beyond primary care is not clear.

This work required all involved to raise their gaze from the individual to focus on health as a shared vision, and to work together in a shared mission. It required individuals prepared to take the risk of crossing the boundaries of geography, discipline and role-expectation, and required leadership teams that were energised by the relationships and opportunities for meaningful work that resulted.

A learning community promoting health across boundaries

What we are learning from listening locally

Through the experience of the authors and those acknowledged at the end of the article, we are beginning to discover how boundary spanning might be systematically facilitated to affect health. Below we underline a few emerging themes, with specific quotes from participants in italics.

Individual leadership is needed to enable collective action

‘Boundary spanning develops language that has shared meaning so that you can communicate across the boundaries of disciplines and different ways of seeing the world.’ Of course, that does not mean that boundaries can be ignored or ploughed down in the process. One of the keys to effective boundary spanning is to recognise the barriers in a situation but work constructively to cross them, often by investing in relationships before tasks. A boundary spanner and successful organisations must learn to interpret ‘What are the walls; what will it take to break down the walls; what will you lose; what do you gain (without losing accountability, quality and professionalism)?’.

Boundary spanners understand that ‘before intention, you have mental models and paradigms. If you can trample (work) in the area of mental models you have potential for change’. Likewise, boundary-spanning organizations understand the importance of creating culture or even setting policies to encourage boundary spanning. ‘Policy is, by definition, a boundary crosser.’

The progress of boundary-spanning efforts can be slow and imprecise. It requires perseverance and time to build a boundary-spanning structures and relationships. It is ‘like changing the temperature in a pool’, a gradual process that can have subtle effects over time. The engaged boundary spanner knows that organizational change is like a ‘big ocean liner – it's hard to turn’. His or her understanding of the role is to ‘start the turning earlier’.

Boundary spanners develop skills to cope with risks and vulnerabilities

‘You are a magnet for arrows when you cross boundaries.’ Often, boundary spanners ‘don't care about size, prestige or income potential’. Sometimes, boundary spanners become leaders in their organisations, setting standards, protocol and culture for others to interact.

An experience of benefit from boundary spanning makes people willing to try it again. An experience of being harmed when boundary spanning makes people averse to the risks and more interested in staying within the apparently safer spaces within boundaries.

Frequently, boundary spanners establish their credibility with mainstream activities, using the resulting influence as a platform for their riskier boundary-spanning work. This may be easier for people who are established in an area than for those who are new or unknown.

Boundary spanning is a team sport that is enabled by shared playing fields

‘We can get into some dangerous waters and have some fun.’ Bringing people together in new ways and establishing reciprocal relationships can spur innovation and make for meaningful work. In addition, people begin to see new opportunities where barriers once existed. It can become contagious and continue to build upon past successes, while encouraging others to join in.

We need to ‘think about boundary-spanning teams that facilitate interorganizational creativity rather than the lonely boundary spanning individual (who often dies young and misunderstood), and also the need for “playgrounds” that span boundaries that people from both (all) sides of a boundary(s) can explore possibilities (e.g. consensus conferences and ThinkTanks, shared geographic space for shared health promotion campaigns and interorganisational innovation using participatory research)’.

There is a complex interplay between individual and organisational contexts

Boundary spanning requires navigating the complex interplay between individual and organisational contexts. In their rules and cultures, organisations can create a framework in which boundary spanning is enabled, but more typically they make it more difficult. ‘The number of people who can capably span boundaries is very small.’

Boundary spanning, whether by one person or an organisation, is grounded in individual qualities, skills and the overall structural landscape. By operating in a supportive landscape with adequate resources, organisations can sustain and value boundary-spanning behaviours and collaborative and innovative work. ‘The more threads, the stronger the fabric.’

Within organisations, a rule of quarters seems to describe the distribution of individuals' perceptions of boundary spanning: ‘A quarter will get it right away, value it and act on it. A quarter will resonate with it, but be too cowed by the dominant culture to voice or act on it. A quarter will not get it and will feel quietly negative about it, but at some future moment will get it and come to value it. A quarter will never get it and will openly deride it.’

The boundary spanner or boundary-spanning organisation brings a mindset of creative possibility. To boundary span is to ‘think differently and deeply’ where ‘innovation comes from thinking in complex and systemic ways about issues’.

The creativity needed for boundary spanning does not easily mesh with the traditional structure of organisations. Within organisations, the boundary-spanning individual faces a tension to stay creative despite the strong push from within an organisation to conform. ‘At the end of the day, the definition of an organisation is to conform. So institutions will always be in tension with creativity.’

Invitation to an ongoing conversation

From these reflections, an initial understanding is emerging – that boundary spanning is important to people, and that it has potential to help individuals, organisations and initiatives to be more effective in ways that enable health. Your participation is needed to further define the role of the boundary spanning in improving health, to discover individuals and organisations engaged in promoting health across boundaries, to develop pilot interorganisational policy for ongoing, multidirectional boundary spanning, and to integrate these new practices to improve health. We invite readers to share their experiences on the PHAB website (www.phab.us) to advance this defining and discovering process.

Please contribute stories and comments that share what has worked and what hasn't in your individual or organisational boundary-spanning efforts. For submission information, please visit: www.phab.us/publications-stories/phab-stories/story-submission, and become a PHAB affiliate: www.phab.us/people/affiliates/ to participate in the further development of a learning community of boundary spanners.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors appreciate very help discussions on boundary spanning for health with: Jeremy Bendik-Keymer, Jessica Berg, Mark Chupp, Robert Ferrer, Shannon French, Gary Galbraith, George Kikano, Marty Kohn, David Loxterkamp, Robert Miller, Laura Nasir, Karen Potter, Julie Rehm, John Ruhl, Roger Saillant, Marvin Schwartz, Paul Thomas, Peter Whitehouse, Sue Flocke and Rhonda Williams. Dr Stange's and Ms Ruhe's time is supported by a Clinical Research Professorship from the American Cancer Society. Dr Stange's time is further supported by the Intergovernmental Personnel Act Mobility Program through the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences at the (US) National Cancer Institute. The opinions expressed in this article are the authors' and not necessarily those of the American Cancer Society or the National Cancer Institute.

Contributor Information

Heide Aungst, Narrative Medical Writer.

Mary Ruhe, Department of Family Medicine.

Kurt C Stange, Professor of Family Medicine, Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Sociology and Oncology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Terry M Allan, Health Commissioner, Cuyahoga County Board of Health, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Elaine A Borawski, Angela Bowen Williamson Professor of Nutrition, Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Co-Director, Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods, Co-Leader, Community Research Partnership Core of the Cleveland Clinical & Translational Science Collaborative.

Colin K Drummond, Director, Coulter-Case Translational Research Partnership, Department of Biomedical Engineering and School of Medicine.

Robert L Fischer, Research Associate Professor, Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences, Co-Director, Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development Faculty, Mandel Center for Nonprofit Organizations.

Ronald Fry, Professor and Chair, Department of Organizational Behavior, Weatherhead School of Management.

Eva Kahana, Robson Professor of Sociology, Humanities, Nursing and Medicine, Director, Elderly Care Research Center Department of Sociology, College of Arts & Sciences.

James A Lalumandier, Professor and Chair of Community Dentistry, School of Dental Medicine.

Maxwell Mehlman, Professor of Bioethics and Law, Schools of Law and Medicine.

Shirley M Moore, Professor and Associate Dean for Research, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Annals of Family Medicine 2009;7(2):100–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas P, Meads G, Moustafa A, Nazareth I, Stange KC. Combined vertical and horizontal integration of health care – a goal of practice based commissioning. Quality in Primary Care 2008;16(6):425–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas P, Nasir L. Could GP commissioning enable collaboration throughout the NHS? London Journal of Primary Care. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American College of Physicians (ACP), American Osteopathic Association (AOA). Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. 2007. www.medicalhomeinfo.org/Joint%20Statement.pdf (accessed 2 July 2011).

- 5.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Stange KC, Stewart E, Jaen C. Transforming physician practices to patient-centered medical homes: lessons from the national demonstration project. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2011;30(3):439–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL. et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2010;25(6):601–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stange KC, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, Jaén CR. Context for understanding the National Demonstration Project and the patient-centered medical home. Annals of Family Medicine 2010;8(Suppl 1):S2–S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA. et al. The group health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Affairs 2010. May;29(5):835–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landon BE, Gill JM, Antonelli RC, Rich EC. Prospects for rebuilding primary care using the patient-centered medical home. Health Affairs 2010. May;29(5):827–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter S. Joint Principles for Accountable Care Organizations. Leawood, KS: American Association of Family Physicians, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClellan M, McKethan AN, Lewis JL, Roski J, Fisher ES. A national strategy to put accountable care into practice. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2010;29(5):982–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care – two essential elements of delivery-system reform. New England Journal of Medicine 2009; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J. et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in Medicare. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2009;28(2):w219–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stange KC. The generalist approach. Annals of Family Medicine 2009;7(3):198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Definition of Health. Geneva: WHO, 1948. www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html (accessed 3 September 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seedhouse D. Health: The Foundations for Achievement (2e) New York: Wiley, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry W. Health is membership. Wirzba N. (ed) The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays of Wendell Berry. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint, 2002, pp. 144–58. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fine M, Peters JW. The Nature of Health: how America lost, and can regain, a basic human value. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stange KC. Power to advocate for health. Annals of Family Medicine 2010;8(2):100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1 21 November 1986 www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf (accessed 31 August 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bechtel C, Ness DL. If you build it, will they come? Designing truly patient-centered health care. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2010. May;29(5):914–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrer RL, Palmer R, Burge S. The family contribution to health status: a population-level estimate. Annals of Family Medicine 2005;3(2):102–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starfield B, Shi LY, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Quarterly 2005;83(3):457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Affairs 2010;29(5):766–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doran T, Roland M. Lessons from major initiatives to improve primary care in the United Kingdom. Health Affairs 2010;29(5):1023–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dentzer S. Reinventing primary care: a task that is far ‘too important to fail’. Health Affairs 2010;29(5):757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care – a perilous journey through the health care system. New England Journal of Medicine 2008;358(10):1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larson EB. Health care system chaos should spur innovation: summary of a report of the Society of General Internal Medicine Task Force on the Domain of General Internal Medicine. Annals of Internal Medicine 2004;140(8):639–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stetler CB, McQueen L, Demakis J, Mittman BS. An organizational framework and strategic implementation for system-level change to enhance research-based practice: QUERI Series. Implementation Science 2008;3:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao JK. Applying findings of public health research to communities: balancing ideal conditions with real-world circumstances. Preventing Chronic Disease 2008;5(2):1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green LW. Public health asks of systems science: to advance our evidence-based practice, can you help us get more practice-based evidence? American Journal of Public Health 2006;96(3):406–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Victora C, Habicht JP, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. American Journal of Public Health 2004;94(3):400–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Awofeso N. What's new about the ‘new public health’? American Journal of Public Health 2004;94(5):705–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kickbusch I. The contribution of the World Health Organization to a new public health and health promotion. American Journal of Public Health 2003;93(3):383–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]