Abstract

Myogenic tone is an intrinsic property of the vasculature that contributes to blood pressure control and tissue perfusion. Earlier investigations assigned a key role in myogenic tone to phospholipase C (PLC) and its products, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). Here, we used the PLC inhibitor, U-73122, and two other, specific inhibitors of PLC subtypes (PI-PLC and PC-PLC) to delineate the role of PLC in myogenic tone of pressurized murine mesenteric arteries. U-73122 inhibited depolarization-induced contractions (high external K+ concentration), thus confirming reports of nonspecific actions of U-73122 and its limited utility for studies of myogenic tone. Edelfosine, a specific inhibitor of PI-PLC, did not affect depolarization-induced contractions but modulated myogenic tone. Because PI-PLC produces IP3, we investigated the effect of blocking IP3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ release on myogenic tone. Incubation of arteries with xestospongin C did not affect tone, consistent with the virtual absence of Ca2+ waves in arteries with myogenic tone. D-609, an inhibitor of PC-PLC and sphingomyelin synthase, strongly inhibited myogenic tone and had no effect on depolarization-induced contraction. D-609 appeared to act by lowering cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration to levels below those that activate contraction. Importantly, incubation of pressurized arteries with a membrane-permeable analog of DAG induced vasoconstriction. The results therefore mandate a reexamination of the signaling pathways activated by the Bayliss mechanism. Our results suggest that PI-PLC and IP3 are not required in maintaining myogenic tone, but DAG, produced by PC-PLC and/or SM synthase, is likely through multiple mechanisms to increase Ca2+ entry and promote vasoconstriction.

Keywords: Bayliss, calcium, phospholipase C, diacylglycerol

it is well accepted that phospholipase C (PLC) is involved in the development and maintenance of myogenic tone. Inhibition of PLC resulted in significant reduction of myogenic tone in studies using pressurized arteries from various arterial beds and species (4, 7, 21, 36). As shown in rat cerebral arteries, the loss of tone is accompanied by membrane hyperpolarization and decrease of cytosolic Ca2+ (21). The functional subtype(s) of PLC involved in the maintenance of tone is, however, unclear. PLC may be generally grouped into two functional subtypes: those that catalyze cleavage of PIP2 (phosphoinositide-specific, PI-PLC) and ones that use phosphatidylcholine as a substrate (phosphatidylcholine-specific, PC-PLC). Cleavage of PIP2 yields inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). On the other hand, cleavage of phosphatidylcholine yields phosphocholine and DAG. Whether the maintenance of tone involves one specific subtype or both subtypes is not clear. Earlier studies have used U-73122, and it has since been determined that U-73122 has undesirable side effects that can affect interpretation of results (18). It is possible to use two different antagonists to discriminate between PLC subtypes. Edelfosine (Ro-14-5243), a synthetic ether lipid, is used to selectively inhibit phosphoinositide-specific PLC (40). D609 is used as an inhibitor for PC-PLC subtype(s) (31). The contribution of one or both types of PLC to the development of myogenic tone can therefore be tested.

We have previously observed that the maintenance of tone in mesenteric arteries in vitro (30, 49) and in mice cremaster arteries in vivo (28) is achieved in the apparent absence of Ca2+ waves. Because waves oftentimes develop involving Ca2+ release from internal stores via IP3 receptors, we reasoned that formation of IP3 and Ca2+ release via IP3 receptors may not be centrally involved in the maintenance of myogenic tone. To account for the virtual absence of Ca2+ waves and the putative role of PLC in the development of tone, we therefore hypothesized that the cleavage of phosphatidylcholine by PC-PLC and formation of DAG plays a critical role in the Bayliss response. The results suggest a central role for phosphatidylcholine and formation of DAG in pressure-induced increases of smooth muscle Ca2+ and myogenic vasoconstriction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pressurized Murine Mesenteric Arteries

Experiments and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Third- and fourth-order mesenteric arteries were dissected and pressurized (Living Systems Instrumentation, St. Albans, VT) following methods described previously (27, 30). Briefly, pressurized mesenteric arteries were perfused at ∼2 ml/min at 35–37°C with a solution of the following composition (in mmol/l): 112 NaCl, 4.9 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25.7 NaHCO3, 2.0 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 11.5 glucose (pH 7.4 at 22°C, bubbled with 5% CO2, 12% O2, and 83% N2). Ca2+-free solution (2 mmol/l EGTA) was used to determine the full passive diameter of arteries. A custom video edge detection system was used to determine diameter (Labview; National Instruments, Austin, TX). Distending pressure was varied from 30 to 110 mmHg to obtain myogenic response curves. The passive diameter at 110 mmHg was used to normalize diameter measurements. Tone was represented as: %diameter = [diameter/diameter(passive 110mmHg)] × 100. In cases where pressure was kept constant at 70 mmHg, diameter measurements are normalized to the passive diameter measured at 70 mmHg. Iberiotoxin, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), U-73122, edelfosine, and xestospongin C were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). D609 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Farmingdale, NY). 1,2-Dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol was from Calbiochem/EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Data are presented as means ± SE; n denotes the number of pressurized arteries. Data comparisons were performed using Student's t-test or ANOVA, as appropriate. A P < 0.05 denoted significant differences.

Confocal Ca2+ Imaging of Pressurized Murine Mesenteric Arteries

Loading of resistance arteries with Ca2+ indicators.

Dissected segments of arteries were loaded with Ca2+ indicator fluo 2-AM using previously described methods (49). After being loaded, the arteries were continuously superfused with gassed Krebs solution and allowed to develop myogenic tone at 70 mmHg, 35–37°C. A Zeiss 5Live slit scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Gottingen, Germany) equipped with a ×40, W C-Apochromat, 1.2 numerical aperture (NA) objective was used for imaging. Excitation of fluo 2 indicator was 488 nm, and the emission was longpass filtered at 505 nm. X-y confocal scans at five frames per second were used to observe Ca2+ waves. Line scans were used to detect Ca2+ sparks. The frequency of sparks was analyzed using the Spark Master Plug-in of ImageJ (39). The frequency of sparks is calculated for a 100-μm wide section of a line scan, thus yielding the unit spark per 100 micrometers per second. The unit reflects the frequency of sparks in a defined physical space corresponding to a subarea inside a single smooth muscle.

Widefield Förster Resonance Energy Transfer/Ca2+ Imaging of Pressurized Murine Mesenteric Arteries

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements with appropriate biosensors provide a robust ratiometric way to quantify cellular parameters without the complications presented by conventional nonratiometric indicators. Whereas nonratiometric measurements can be confounded by factors such as focal plane, specimen movement, and concentration of indicator molecule (to name a few), ratiometric FRET measurements are less affected by these factors. The exMLCK FRET biosensor can reliably report Ca2+ levels and myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) activity. Here we use mesenteric arteries from mice expressing the exMLCK biosensor in vascular smooth muscle (19, 45). Arteries were imaged using an Olympus MVX10 microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) (objective lens: 2× Plan Apochromat, 0.5 NA) equipped with “DualView” optics (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and a Hamamatsu Orca-ER camera (Japan) as described previously (48, 50). Briefly, cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) excitation was at 426–446 nm [CFP emission = 455–485 nm, yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) emission = 520–550 nm]. Data were corrected for spectral bleedthrough (26). The CFP-to-YFP ratio at 30 mmHg (R30) under control conditions was used to normalize ratio measurements (R/R30) (where R is the ratio at a particular pressure) thus allowing for grouping of data.

RESULTS

Myogenic Tone and PLC: “PI-PLC and PC-PLC”

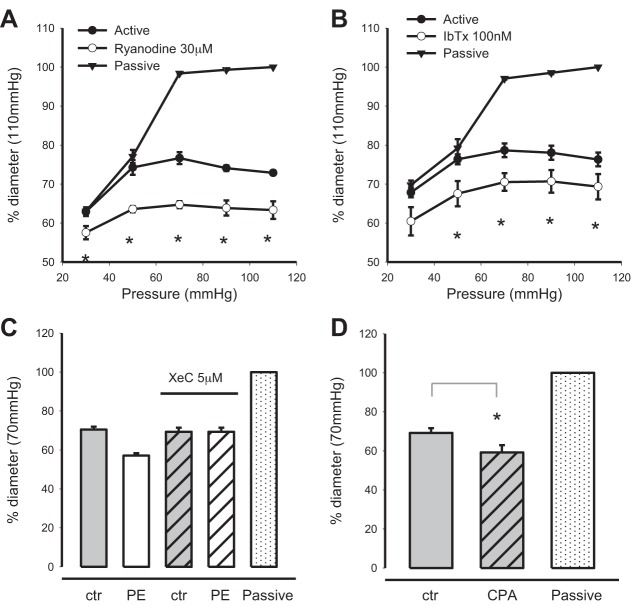

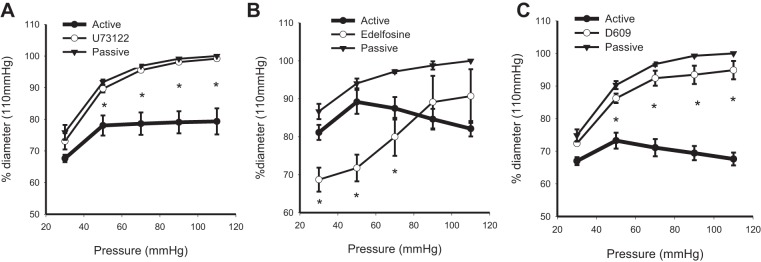

U-73122 is routinely used as a general-purpose inhibitor of PLC. Treatment of arteries that have developed myogenic tone with 3 μM U-73122 (n = 8) resulted in a complete loss of myogenic reactivity (Fig. 1A). Arteries followed the passive diameter curve after treatment with U-73122, in agreement with earlier studies (21, 36). Edelfosine is an ether lysophospholipid that effectively inhibits PLC activity and catalysis of PIP2, but without undesirable side effects seen with U-73122 (18, 40). In this regard it can be considered a preferred inhibitor for “PI-PLC.” Treatment of arteries with edelfosine resulted in an increase of tone at pressures of 30–70 mmHg (n = 7). Myogenic tone was unaltered at the higher pressures (Fig. 1B). D609 is a xanthate compound that has been shown to competitively inhibit phosphatidylcholine-specific PLC (Ki = 6.4 μM) without affecting phosphatidylinositol-specific PLC (2). D609 is known to inhibit catabolism of phosphatidylcholine via a PLC-type reaction (31). Incubation of pressurized arteries with 10 μM D609 resulted in significant loss of myogenic tone at the pressures tested (30–110 mmHg, n = 5). For example, at 110 mmHg, while arteries maintained a diameter of 67.6 ± 1.9% of passive under control conditions, incubation with D609 resulted in significant vasodilation to 94.8 ± 2.8% (Fig. 1C). Myogenic tone is therefore “D609 sensitive” in murine mesenteric arteries.

Fig. 1.

Effects of phospholipase C inhibitors on myogenic tone of isobaric murine mesenteric arteries. The myogenic response of pressurized murine mesenteric arteries under control and in the presence of U-73122 (3 μM, n = 8; A), edelfosine (20 μM, n = 7, B), and D609 (10 μM, n = 5, C) is shown. Passive curves are obtained in 0 Ca2+ solution (*P < 0.05, active vs. drug).

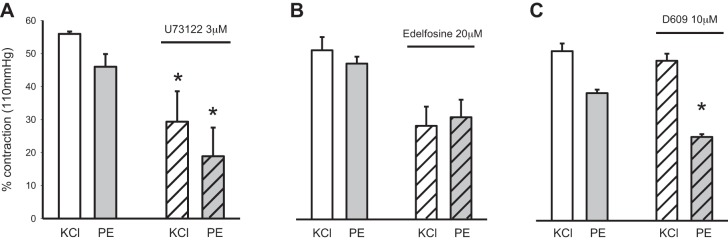

We also quantified the contraction of arteries to treatment with 60 mM KCl or 10 μM phenylephrine (PE) before and after incubation with PLC antagonists. Treatment with U-73122 significantly reduced the contraction of pressurized arteries to stimulation with KCl and PE (n = 5) (Fig. 2A). The response of arteries to PE and KCl remained unchanged in the presence of edelfosine (n = 6) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, D609 significantly reduced the contraction to PE (n = 4), whereas the contraction to bath application of 60 mM KCl remained unaffected (n = 7) (Fig. 2C). Thus, D609 treatment results in loss of myogenic tone without concomitant changes in the contraction of arteries via depolarization with 60 mM KCl.

Fig. 2.

Effects of phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitors on the contractile response of isobaric murine mesenteric arteries to stimulation with KCl and phenylephrine (PE). A: U-73122 (3 μM, n = 5, *P < 0.05) wide-spectrum PLC inhibitor. B: edelfosine (20 μM, n = 6, P = 0.06) phosphoinositide-specific (PI-PLC) inhibitor. C: D609 [10 μM (n = 7; KCl, n = 4 PE), *P < 0.05] phosphatidylcholine-specific (PC-PLC)/smooth muscle (SM) synthase inhibitor. Arteries were stimulated with 60 mM KCl or 10 μM PE at 70 mmHg, 37°C.

Overall, the above results indicate that the development of myogenic tone is a D609-sensitive process. The results also suggest that the activity of PI-PLC can be modulatory to myogenic tone.

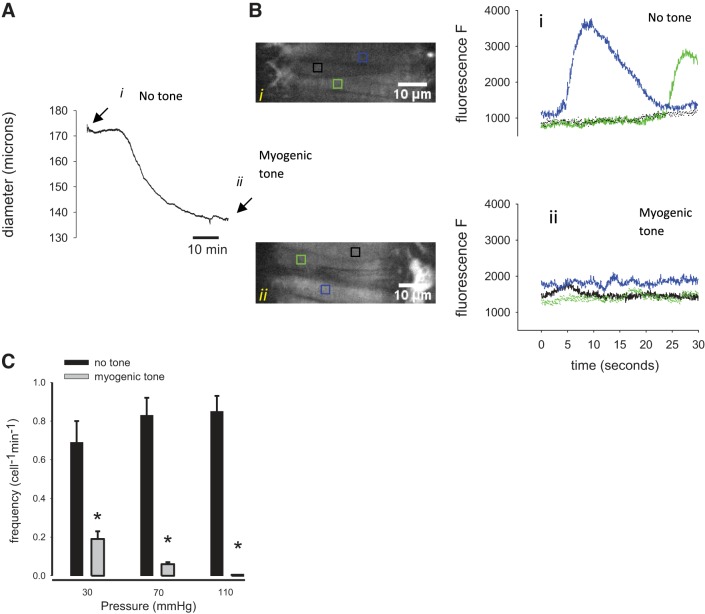

Ca2+ signals during established myogenic tone.

The diameter of an artery during development of myogenic tone is shown in Fig. 3A. Arteries loaded with Ca2+ indicator (fluo 2-AM) were imaged before development of myogenic tone (Fig. 3Ai) and after myogenic tone has been established (Fig. 3Aii). Smooth muscle cells from two separate regions of an artery are imaged before and after development of tone (Fig. 3B). Figure 3B shows typical x–y confocal scans used to derive the Ca2+ fluorescence signals in individual smooth muscle cells under no tone (Fig. 3Bi) and myogenic tone (Fig. 3Bii) conditions. Ca2+ waves appear as high-amplitude long-duration events (Fig. 3Bi). These prominent Ca2+ signals were not readily observed when myogenic tone was established (Fig. 3Bii). The frequencies of observed Ca2+ waves in mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells are significantly reduced at all observed pressures after the development of myogenic tone. Whereas the frequencies of waves at 30, 70, and 110 mmHg before tone are (cell−1/min) 0.69 ± 0.11, 0.83 ± 0.09, and 0.85 ± 0.08 (n = 4), respectively, the frequencies were significantly reduced to 0.19 ± 0.04, 0.06 ± 0.01, and 0.0 (Fig. 3, B and C) after tone has developed. Ca2+ waves are therefore virtually absent in mouse pressurized mesenteric arteries that have developed myogenic tone.

Fig. 3.

Ca2+ signals in pressurized murine mesenteric arteries before and after development of myogenic tone. A: the diameter of a pressurized (70 mmHg) mesenteric artery is shown. Ca2+ fluorescence signals were obtained before (i, arrow) and after (ii, arrow) development of myogenic tone as shown in the diameter trace. B: typical x–y confocal scans (first column) used to calculate fluorescence values from single arterial myocytes show a virtual absence of high-amplitude, long-duration Ca2+ waves after development of myogenic tone (Bii, bottom, fluo 2-AM). C: summary bar graph depicting the frequency of Ca2+ waves in pressurized arterial myocytes (n = 4, *P < 0.05) before and after development of myogenic tone.

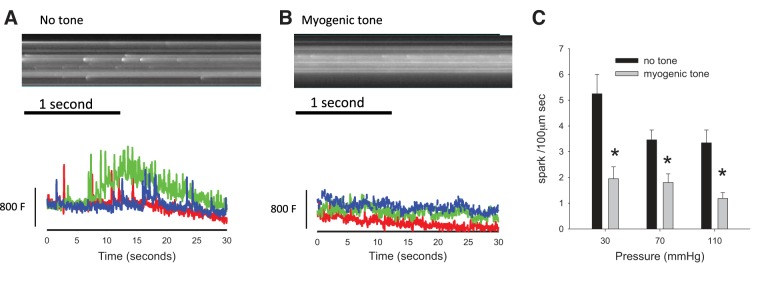

The frequency of Ca2+ sparks before and after development of myogenic tone was also determined. Figure 4, A and B, shows typical line scans of smooth muscle cells that illustrate spontaneous Ca2+ sparks before and after development of myogenic tone. Sparks are evident in both the line scan images and in the intensity profile plots. The current method used here employing Ca2+ indicator dyes can potentially underestimate the frequency of sparks because of generally elevated fluorescence levels corresponding to increased steady-state levels of Ca2+. Figure 4C shows the summary of spark frequencies at different distending pressures. At a pressure of 70 mmHg and no tone, spark frequency was 3.46 ± 0.38 sparks·100 μm−1·s−1. After development of myogenic tone Ca2+ sparks were still present, but an apparent decrease in the frequencies was observed at all pressures (e.g., 70 mmHg, 1.80 ± 0.34 sparks·100 μm−1·s−1).

Fig. 4.

Frequency of Ca2+ sparks in isobaric murine mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells during maintained myogenic constriction. A and B: representative line scans of pressurized murine mesenteric arteries loaded with Ca2+ indicator illustrate the prevalence of Ca2+ sparks before and after the development of myogenic tone. The frequency of sparks is calculated for a 100-μm-wide section of a line scan, thus yielding the unit spark·100 μm−1·s−1. C: summary bar graph indicating a decrease in the frequency of Ca2+ sparks in smooth muscle cells during established myogenic tone. A and B, bottom: fluorescence units (F); bar is equivalent to 800 units. *P < 0.05, no tone vs. myogenic tone.

Modulation of tone via internal Ca2+ stores.

Paired recordings of the myogenic response were obtained from mesenteric arteries under control conditions and in the presence of ryanodine (30 μM, n = 3) (Fig. 5A) and iberiotoxin [Ca2+-dependent K+ (KCa) channel antagonist] (100 nM, n = 4) (Fig. 5B). Both ryanodine and iberiotoxin caused significant increases in myogenic tone at pressures of 30–110 mmHg. Likewise, reduction of Ca2+ content of sarcoplasmic reticulum via incubation of arteries with CPA (10 μM, n = 5) (Fig. 5D) significantly increases myogenic tone. Incubation of arteries with xestospongin C (5 μM, n = 2) (Fig. 5C) to block IP3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ release did not change myogenic tone but effectively blocked contraction in response to bath-applied PE (10 μM). Together, the above results indicate that myogenic tone can be modulated by internal Ca2+ stores.

Fig. 5.

Modulation of myogenic tone by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores. The effects of blockade of ryanodine receptors (30 μM ryanodine) (A) and Ca2+-dependent K+ (KCa) channels [100 nM iberiotoxin (IbTx)] (B) on myogenic tone of pressurized murine mesenteric arteries were measured. C: xestospongin C (5 μM, XeC) was used to block Ca2+ release via inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors. XeC did not affect myogenic tone but eliminated the contractile response to bath-applied PE (10 μM). D: incubation of arteries with 10 μM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) significantly increased myogenic tone. Passive diameter was measured with 0 Ca2+ perfusate (*P < 0.01). ctr, Control.

Inhibition of PC-PLC/sphingomyelin synthase and smooth muscle Ca2+.

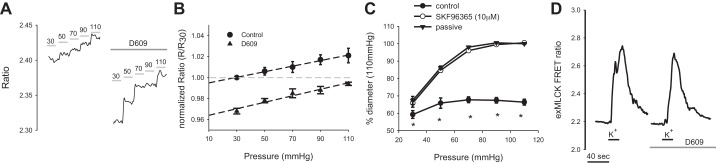

Step increases in pressure resulted in increases of the FRET ratio (Fig. 6A) indicating step increases of smooth muscle Ca2+. The FRET ratio response in the same artery was significantly reduced after treatment with D609. Pressure-induced changes in the FRET ratio still occur, but ratios achieved are significantly attenuated (n = 3, Fig. 6B). A linear curve fit of both response curves shows a similar slope between the control and D609 curve. The dynamic response of exMLCK biosensor is unaltered in the presence of D609 as shown by the FRET response to depolarization with 117 mM K+ (n = 3, Fig. 6D). Control peak response was 2.95 ± 0.12 and in D609 2.91 ± 0.11. Catalysis of phosphatidylcholine by PC-PLC will produce DAG. Because DAG is known to gate some transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, we determined the effect of inhibition of nonselective cation channels with SKF-96365 and found significant loss of myogenic tone (n = 3, Fig. 6C), similar to that seen for D609. The results with SKF-96365 compound suggest downstream involvement of TRP-type channels.

Fig. 6.

Effects of inhibition of PC-PLC/sphingomyelin synthase on pressure-induced Ca2+ response of murine mesenteric smooth muscle cells. A: the Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) ratio response in a pressurized mesenteric artery expressing exMLCK biosensor is shown under control and after treatment with D609 (10 μM, n = 3). B: summary of the pressure-induced FRET response of mesenteric arteries [normalized ratio at a particular pressure (R) to that at 30 mmHg (R30)] before and after treatment with D609, n = 3. C: myogenic tone in mesenteric arteries under control and after treatment with SKF-96365, n = 3. *P < 0.05, control vs. SKF-96365. D: FRET response of exMLCK biosensor to depolarization with 117 mM K+ in the absence and presence of D609 (n = 3).

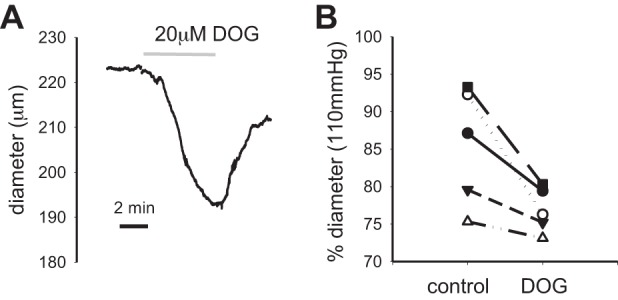

DAG analog and arterial diameter.

Figure 7A shows that treatment of a pressurized murine mesenteric artery (50 mmHg) with 20 μM 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol results in vasoconstriction of the artery. Figure 7B shows the significant constriction of arteries after exposure to the DAG analog (n = 5).

Fig. 7.

Effects of membrane-permeable diacylglycerol (DAG) analog on diameter of pressurized murine mesenteric arteries. A: the diameter response of a pressurized mesenteric artery in response to treatment with 1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol (DOG, 20 μM, 50 mmHg) is shown. B: summary of the response of arteries to treatment with DOG (n = 5).

DISCUSSION

Uncontrolled Side Effects of U-73122

The majority of earlier studies on the role of PLC in myogenic tone have used U-73122 to indicate that PLC and, by extension, IP3 and DAG were involved in the development and maintenance of myogenic tone. U-73122 has other undesirable side effects that prevent clear and unequivocal interpretation of results. These have included inhibition of K+ currents and a Gi\Go-mediated activation of an inward rectifying K+ current (18). The mechanism by which the side effects occur is likely via alkylation reactions of U-73122. Importantly, in the case of myogenic constriction, U-73122 is known to inhibit voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx via dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ channels in a neuronal cell line (NG108-15) (22). The loss of tone, hyperpolarization, and decrease in cytosolic Ca2+ of myogenically active arteries when treated with U-73122 may therefore take effect via inhibition of dihydropyridine-sensitive channels (L-type Ca2+ channels) and not necessarily via mechanisms involving PLC. Our present results recapitulate this concern, since it is clear that U-73122 not only inhibits myogenic tone (Fig. 1A) but also depolarization-induced constriction of arteries (Fig. 2A).

Phosphatidylinositol-Specific PLC

Although PLC is classified as either PI-PLC or PC-PLC, the mammalian gene(s) that correspond to such enzymes are not cloned (1). The classification of PI-PLC and PC-PLC in mammalian cells is therefore a functional classification and does not necessarily translate to a particular gene product. The ability of edelfosine to elicit Ca2+ release from internal stores and subsequent Ca2+ entry (as seen in MDCK cells) (20) may account for the trend of increase in myogenic tone. The mechanism by which edelfosine may elicit Ca2+ release from internal stores of vascular smooth muscle cells is incompletely understood. Given that we have used effective doses of edelfosine (20 μM), we conclude that PI-PLC enzymatic activity is not obligatory for the maintenance of myogenic tone in murine resistance-sized mesenteric arteries. PI-PLC, however, exerts a modulatory role since edelfosine was able to induce detectable increases in tone.

Modulation of Myogenic Tone via Ryanodine Receptor-Mediated Ca2+ Release

Ca2+ waves are virtually absent in myogenically active, pressurized murine mesenteric arteries (Fig. 3B), consistent with earlier findings (28, 30). Incubation of arteries with the membrane-permeable inhibitor of IP3 receptors, xestospongin C (10), did not affect established myogenic tone at doses that were effective at inhibiting PE-induced contractions (Fig. 5C). The results with xestospongin C treatment suggest that IP3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ release and Ca2+ waves do not exert strong influence on myogenic responses of murine mesenteric arteries. The results with inhibition of IP3 receptors in murine mesenteric arteries are different from results obtained from rat cerebral arteries where Ca2+ release via IP3 receptors seem to hold a more prominent role in establishing myogenic responses (13). In contrast, Ca2+ release via ryanodine receptor channels does have significant effects on myogenic tone in murine mesenteric arteries. Depletion of CPA-sensitive Ca2+ stores with CPA and inhibition of ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca2+ release with ryanodine both significantly increase myogenic constriction (Fig. 5, A and D). Whereas sparks are present in myogenically active arteries, incubation of arteries with iberiotoxin also resulted in a similar increase in tone as that seen for ryanodine treatment. The above results are in accord with earlier studies in cerebral arterioles (34, 38) whereby sparks are postulated to activate Ca2+-dependent KCa currents, thus exerting vasodilatory influence on arteries. Prevention of sparks or blockade of KCa channels causes vasoconstriction because of inhibition of a hyperpolarizing KCa current. The results with ryanodine and iberiotoxin treatment both suggest that KCa channels play a similar role in the rat cerebral arteries and mouse mesenteric arteries. Alternatively, the increase in tone seen with CPA treatment may also arise from the ability of CPA treatment to increase the activity of mechanosensitive cation channels in vascular smooth muscle (37). An increase in depolarizing cationic current would depolarize smooth muscle, thus promoting vasoconstriction. Overall, the results suggest a modulatory role for the sarcoplasmic reticulum and Ca2+ release via ryanodine receptors in determining myogenic responses.

Phosphatidylcholine-Specific PLC and Sphingomyelin Synthase

Arteries treated with D609 lost myogenic tone (Fig. 1C) and attenuated pressure-induced Ca2+ responses (Fig. 6). The loss of tone occurs without any concomitant effects on depolarization-induced contraction, and thus the ability of the artery to contract. Although pressure-induced Ca2+ responses are still detectable, D609 treatment shifted the entire response curve downward, thus lowering Ca2+ levels and preventing the elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ to levels that are permissive for contraction of the pressurized artery. Interestingly, the result with D609 is in contrast to an earlier study in rat posterior cerebral arteries where D609 did not inhibit myogenic vasoconstrictions (21). It is therefore possible that differences in arterial beds (mesentery and cerebral) as well as species differences may account for the differences observed.

Whereas D609 is a selective inhibitor for PC-PLC (2), as opposed to PI-PLC, D609 is also known to inhibit sphingomyelin synthase (SMS) (24). It is of note that both PC-PLC and SMS catalyze reactions that use PC and yield DAG as a downstream product. Inhibition of PC-PLC and/or SMS is expected to diminish formation of DAG. Investigators have even suggested that SMS may account for the D609-sensitive mammalian PC-PLC (24). SMS family members are integral membrane proteins, and SMS 2 has been observed in the plasma membrane (17). The steps involved in the regulation of SMS enzymatic activity are less understood at this point. However, it is interesting to note that hypoxia can induce a cellular accumulation of DAG in multiple cell types (12, 43, 47) and that this response can be sensitive to inhibition of PC-PLC/SMS with D609 (43). Thus it seems that the activity of PC-PLC/SMS may be regulated via multiple stimulus modalities. The results presented here are consistent with the hypothesis that the activity of PC-PLC/SMS is central for the development of stretch-induced Ca2+ responses and myogenic vasoconstriction in murine mesenteric arteries.

Bayliss Mechanism and a Central Role for PC and DAG

Mechanically induced, ligand-independent activation of certain Gq/11-coupled receptors may constitute an early step in the mechanotransduction process involved in the myogenic response (29, 51). More recently, investigators have reported that ligand-independent activation of angiotensin type 1 (AT1) receptors plays a significant role in the myogenic responses of pressurized murine mesenteric arteries (6, 41). Whether it is AT1A or AT1B that is centrally involved is a subject of discussion, since the two abovementioned studies point to either AT1A or AT1B. Other metabotropic receptors, including endothelin (ETA) and α1-receptors, may also be involved in sensing mechanical stretch, and different arrays of G protein-coupled receptors may participate in sensing mechanical stretch in other arterial arcades (6, 28). In addition, the involvement of particular receptors/signaling cascade may vary not only with the arterial arcade but also with the physiological state of the animal (15). The signaling steps downstream of activation of Gq\11-coupled receptors are less understood. However, investigators have demonstrated that particular G protein-coupled receptors have detectable “gating currents” and may be activated/modulated by membrane depolarization itself (5, 25). Furthermore, dihydropyridine receptors may act as voltage sensors and trigger Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (3, 9). In this manner, the receptors (G protein coupled or dihydropyridine) can potentially participate in the myogenic response, albeit downstream of earlier mechanotransduction steps.

Mechanical stretch can lead to activation of particular cation channels (8, 35, 42, 44, 46). Recordings of the mechanosensitive currents show biophysical properties akin to TRP family of proteins (8, 37, 44). Treatment of arteries with SKF-96365 abolishes myogenic tone, suggesting the probability of downstream involvement of TRP-type cation channels. Downstream inhibition of an XE991-sensitive K+ current has been demonstrated to also modulate myogenic responses, but the mechanism for inhibition remains unsorted (41). Importantly, mechanical stretch is known to increase DAG in smooth muscle cells (32). A membrane-permeable DAG analog can augment activation of the mechanosensitive currents in smooth muscle (37) and tone (7, 11). Critically, treatment of pressurized murine mesenteric arteries with a DAG analog does induce vasoconstriction. DAG action may include activation of TRP channels, protein kinase C (PKC) enzyme which can lead to modulation of Ca2+ sparklets (33), as well as Ca2+ sensitivity. Further studies will be required to further delineate the mechanisms involved.

The present results suggest that catalysis of PC and formation of DAG are critical steps for the Bayliss response as seen in murine mesenteric arteries. The spatiotemporal pattern of DAG formation in response to increases in distending pressure in arteries was not determined in this study and should be a subject of future inquiry. Because D609 can inhibit PC-PLC and SMS, studies to differentiate between the two enzymes will also be needed. Murine knockout models for SMS 1 and 2 are available and may aid in this respect (14, 23).

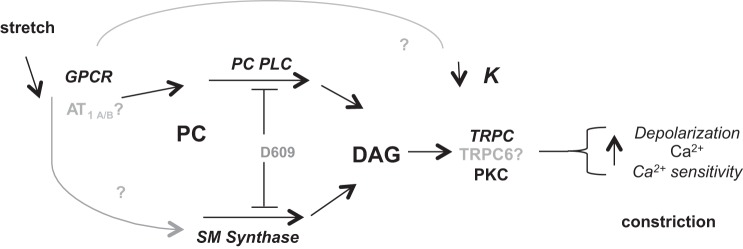

In summary, we hypothesize that the Bayliss response proceeds as follows (Fig. 8): ligand-independent, stretch-induced activation of G protein-coupled receptors (including AT1) would be responsible for 1) activation of PC-PLC/SMS and formation of DAG and 2) inhibition of a K+ conductance (41). Downstream actions of DAG, which include activation of particular TRP-type channels (16) and PKC enzymatic activity, may then contribute to depolarization, Ca2+ influx, increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration, Ca2+ sensitivity, and vasoconstriction.

Fig. 8.

Proposed role of PC-PLC/sphingomyelin synthase in the myogenic response of murine mesenteric arteries. Mechanical stretch of the plasma membrane leads to ligand-independent activation of G protein-coupled receptors [GPCRs, including angiotensin type 1 (AT1)]. D609-sensitive PC-PLC and/or sphingomyelin synthase activate and use phosphatidylcholine to yield DAG metabolite. DAG activates plasma membrane currents, including transient receptor potential C (TRPC) family members and protein kinase C (PKC). Inhibition of a K+ current also contributes to depolarization. The resultant increase in Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ sensitivity thus leads to myogenic vasoconstriction.

GRANTS

The work presented was funded by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 5R01-HL-091969 to W. G. Wier.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.R.H.M. and J.Z. conception and design of research; J.R.H.M., J.Z., and S.T.F. performed experiments; J.R.H.M., J.Z., S.T.F., and W.G.W. analyzed data; J.R.H.M. and W.G.W. interpreted results of experiments; J.R.H.M., J.Z., and S.T.F. prepared figures; J.R.H.M. and J.Z. drafted manuscript; J.R.H.M., S.T.F., and W.G.W. edited and revised manuscript; J.R.H.M., J.Z., S.T.F., and W.G.W. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF, Gusain A. Tricyclodecan-9-yl-xanthogenate (D609) mechanism of actions: a mini-review of literature. Neurochem Res 37: 671–679, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amtmann E. The antiviral, antitumoural xanthate D609 is a competitive inhibitor of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C. Drugs Exp Clin Res 22: 287–294, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araya R, Liberona JL, Cardenas JC, Riveros N, Estrada M, Powell JA, Carrasco MA, Jaimovich E. Dihydropyridine receptors as voltage sensors for a depolarization-evoked, IP3R-mediated, slow calcium signal in skeletal muscle cells. J Gen Physiol 121: 3–16, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakker EN, Kerkhof CJ, Sipkema P. Signal transduction in spontaneous myogenic tone in isolated arterioles from rat skeletal muscle. Cardiovasc Res 41: 229–236, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Chaim Y, Chanda B, Dascal N, Bezanilla F, Parnas I, Parnas H. Movement of ‘gating charge’ is coupled to ligand binding in a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 444: 106–109, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blodow S, Schneider H, Storch U, Wizemann R, Forst AL, Gudermann T, Mederos Schnitzler M Y. Novel role of mechanosensitive AT receptors in myogenic vasoconstriction. Pflugers Arch 466: 1343–1353, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coats P, Johnston F, MacDonald J, McMurray JJ, Hillier C. Signalling mechanisms underlying the myogenic response in human subcutaneous resistance arteries. Cardiovasc Res 49: 828–837, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis MJ, Donovitz JA, Hood JD. Stretch-activated single-channel and whole cell currents in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 262: C1083–C1088, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Valle-Rodriguez A, Lopez-Barneo J, Urena J. Ca2+ channel-sarcoplasmic reticulum coupling: a mechanism of arterial myocyte contraction without Ca2+ influx. EMBO J 22: 4337–4345, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gafni J, Munsch JA, Lam TH, Catlin MC, Costa LG, Molinski TF, Pessah IN. Xestospongins: potent membrane permeable blockers of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Neuron 19: 723–733, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gokina NI, Knot HJ, Nelson MT, Osol G. Increased Ca2+ sensitivity as a key mechanism of PKC-induced constriction in pressurized cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1178–H1188, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg M, Zhang HL, Steinberg SF. Hypoxia alters the subcellular distribution of protein kinase C isoforms in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. J Clin Invest 99: 55–61, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzales AL, Yang Y, Sullivan MN, Sanders L, Dabertrand F, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT, Earley S. A PLCgamma1-dependent, force-sensitive signaling network in the myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries. Sci Signal 7: 327–349, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hailemariam TK, Huan C, Liu J, Li Z, Roman C, Kalbfeisch M, Bui HH, Peake DA, Kuo MS, Cao G, Wadgaonkar R, Jiang XC. Sphingomyelin synthase 2 deficiency attenuates NFkappaB activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 1519–1526, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoefer J, Azam MA, Kroetsch JT, Leong-Poi H, Momen MA, Voigtlaender-Bolz J, Scherer EQ, Meissner A, Bolz SS, Husain M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate-dependent activation of p38 MAPK maintains elevated peripheral resistance in heart failure through increased myogenic vasoconstriction. Circ Res 107: 923–933, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature 397: 259–263, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holthuis JC, Luberto C. Tales and mysteries of the enigmatic sphingomyelin synthase family. Adv Exp Med Biol 688: 72–85, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horowitz LF, Hirdes W, Suh BC, Hilgemann DW, Mackie K, Hille B. Phospholipase C in living cells: activation, inhibition, Ca2+ requirement, and regulation of M current. J Gen Physiol 126: 243–262, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isotani E, Zhi G, Lau KS, Huang J, Mizuno Y, Persechini A, Geguchadze R, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Real-time evaluation of myosin light chain kinase activation in smooth muscle tissues from a transgenic calmodulin-biosensor mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 6279–6284, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jan CR, Wu SN, Tseng CJ. The ether lipid ET-18-OCH3 increases cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations in Madin Darby canine kidney cells. Br J Pharmacol 127: 1502–1510, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarajapu YP, Knot HJ. Role of phospholipase C in development of myogenic tone in rat posterior cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H2234–H2238, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin W, Lo TM, Loh HH, Thayer SA. U73122 inhibits phospholipase C-dependent calcium mobilization in neuronal cells. Brain Res 642: 237–243, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Fan Y, Liu J, Li Y, Huan C, Bui HH, Kuo MS, Park TS, Cao G, Jiang XC. Impact of sphingomyelin synthase 1 deficiency on sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 1577–1584, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luberto C, Hannun YA. Sphingomyelin synthase, a potential regulator of intracellular levels of ceramide and diacylglycerol during SV40 transformation. Does sphingomyelin synthase account for the putative phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C? J Biol Chem 273: 14550–14559, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahaut-Smith MP, Martinez-Pinna J, Gurung IS. A role for membrane potential in regulating GPCRs? Trends Pharmacol Sci 29: 421–429, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mauban JR, Fairfax ST, Rizzo MA, Zhang J, Wier WG. A method for noninvasive longitudinal measurements of [Ca2+] in arterioles of hypertensive optical biosensor mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H173–H181, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauban JR, Lamont C, Balke CW, Wier WG. Adrenergic stimulation of rat resistance arteries affects Ca2+ sparks, Ca2+ waves, and Ca2+ oscillations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2399–H2405, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mauban JR, Zacharia J, Zhang J, Wier WG. Vascular tone and Ca(2+) signaling in murine cremaster muscle arterioles in vivo. Microcirculation 20: 269–277, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mederos y Schnitzler M, Storch U, Meibers S, Nurwakagari P, Breit A, Essin K, Gollasch M, Gudermann T. Gq-coupled receptors as mechanosensors mediating myogenic vasoconstriction. EMBO J 27: 3092–3103, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miriel VA, Mauban JR, Blaustein MP, Wier WG. Local and cellular Ca2+ transients in smooth muscle of pressurized rat resistance arteries during myogenic and agonist stimulation. J Physiol 518: 815–824, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller-Decker K. Interruption of TPA-induced signals by an antiviral and antitumoral xanthate compound: inhibition of a phospholipase C-type reaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 162: 198–205, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Narayanan J, Imig M, Roman RJ, Harder DR. Pressurization of isolated renal arteries increases inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H1840–H1845, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Navedo MF, Santana LF. CaV1.2 sparklets in heart and vascular smooth muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 58: 67–76, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science 270: 633–637, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohya Y, Adachi N, Nakamura Y, Setoguchi M, Abe I, Fujishima M. Stretch-activated channels in arterial smooth muscle of genetic hypertensive rats. Hypertension 31: 254–258, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osol G, Laher I, Kelley M. Myogenic tone is coupled to phospholipase C and G protein activation in small cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 265: H415–H420, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park KS, Kim Y, Lee YH, Earm YE, Ho WK. Mechanosensitive cation channels in arterial smooth muscle cells are activated by diacylglycerol and inhibited by phospholipase C inhibitor. Circ Res 93: 557–564, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez GJ, Bonev AD, Patlak JB, Nelson MT. Functional coupling of ryanodine receptors to KCa channels in smooth muscle cells from rat cerebral arteries. J Gen Physiol 113: 229–238, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Picht E, Zima AV, Blatter LA, Bers DM. SparkMaster: automated calcium spark analysis with ImageJ. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1073–C1081, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Powis G, Seewald MJ, Gratas C, Melder D, Riebow J, Modest EJ. Selective inhibition of phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C by cytotoxic ether lipid analogues. Cancer Res 52: 2835–2840, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schleifenbaum J, Kassmann M, Szijarto IA, Hercule HC, Tano JY, Weinert S, Heidenreich M, Pathan AR, Anistan YM, Alenina N, Rusch NJ, Bader M, Jentsch TJ, Gollasch M. Stretch-activation of angiotensin II type 1a receptors contributes to the myogenic response of mouse mesenteric and renal arteries. Circ Res 115: 263–272, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Setoguchi M, Ohya Y, Abe I, Fujishima M. Stretch-activated whole-cell currents in smooth muscle cells from mesenteric resistance artery of guinea-pig. J Physiol 501: 343–353, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Temes E, Martin-Puig S, Aragones J, Jones DR, Olmos G, Merida I, Landazuri MO. Role of diacylglycerol induced by hypoxia in the regulation of HIF-1alpha activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 315: 44–50, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Welsh DG, Morielli AD, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Transient receptor potential channels regulate myogenic tone of resistance arteries. Circ Res 90: 248–250, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wier WG, Rizzo MA, Raina H, Zacharia J. A technique for simultaneous measurement of Ca2+, FRET fluorescence and force in intact mouse small arteries. J Physiol 586: 2437–2443, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X, Davis MJ. Characterization of stretch-activated cation current in coronary smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H1751–H1761, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoshioka K, Clejan S, Fisher JW. Activation of protein kinase C in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HEP3B) cells increases erythropoietin production. Life Sci 63: 523–535, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zacharia J, Mauban JR, Raina H, Fisher SA, Wier WG. High vascular tone of mouse femoral arteries in vivo is determined by sympathetic nerve activity via alpha1A- and alpha1D-adrenoceptor subtypes. PLoS One 8: e65969, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zacharia J, Zhang J, Wier WG. Ca2+ signaling in mouse mesenteric small arteries: myogenic tone and adrenergic vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1523–H1532, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J, Chen L, Raina H, Blaustein MP, Wier WG. In vivo assessment of artery smooth muscle [Ca2+]i and MLCK activation in FRET-based biosensor mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H946–H956, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zou Y, Akazawa H, Qin Y, Sano M, Takano H, Minamino T, Makita N, Iwanaga K, Zhu W, Kudoh S, Toko H, Tamura K, Kihara M, Nagai T, Fukamizu A, Umemura S, Iiri T, Fujita T, Komuro I. Mechanical stress activates angiotensin II type 1 receptor without the involvement of angiotensin II. Nat Cell Biol 6: 499–506, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]