Abstract

The dimorphic fungi Paracoccidioides spp. are the etiological agents of paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM), a mycosis of high incidence in Brazil. The toxicity of drug treatment and the emergence of resistant organisms have led to research for new candidates for drugs. In this study, we demonstrate that the natural product argentilactone was not cytotoxic or genotoxic to MRC5 cells at the IC50 concentration to the fungus. We also verified the proteomic profile of Paracoccidioides lutzii after incubation with argentilactone using a label free quantitative proteome nanoUPLC-MSE. The results of this study indicated that the fungus has a global metabolic adaptation in the presence of argentilactone. Enzymes of important pathways, such as glycolysis, the Krebs cycle and the glyoxylate cycle, were repressed, which drove the metabolism to the methylcytrate cycle and beta-oxidation. Proteins involved in cell rescue, defense and stress response were induced. In this study, alternative metabolic pathways adopted by the fungi were elucidated, helping to elucidate the course of action of the compound studied.

Keywords: Paracoccidioides lutzzi, paracoccidioidomycosis, proteomic, argentilactone, antifungal

Introduction

The fungi of the genus Paracoccidioides are thermally dimorphic and cause paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM), a human systemic mycosis prevalent in residents of Latin America (Brummer et al., 1993). In Brazil, systemic mycoses are a major cause of mortality considering infectious diseases and the PCM contributes by more than half of the deaths caused by fungal infections (Prado et al., 2009). An essential step for the establishment of the Paracoccidioides spp. infection is the transition from mycelium to the yeast form. The fungus lives in the environment as mycelial form, which produces propagules that can be inhaled by the host where change to the yeast phase, causing the infection (Franco, 1987).

Due to toxicity of drug treatment (Travassos et al., 2008) and the appearance of resistance strains (Hahn et al., 2003), new therapeutic approaches for the treatment of PCM have been suggested (Rittner et al., 2012). Natural compounds, synthetic, and semi-synthetic derivatives with antifungal activity against Paracoccidioides spp. have been investigated (Johann et al., 2012; Zambuzzi-Carvalho et al., 2013). Argentilactone, the major component of Hyptis ovalifolia essential oil, a natural Brazilian plant, inhibits the growth of P. lutzii yeast cells, the dimorphism, and the activity of the glyoxylate cycle key enzyme isocitrate lyase (PbICL) (Prado et al., 2014). In addition, argentilactone inhibits the proliferation of Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida albicans, Tricophyton rubrum, Tricophyton mentagrophyte, Microsporum gypseum, and Microsporum canis (Oliveira et al., 2004).

Several antifungals drugs act by mechanisms poorly understood. New approaches such as genomics and proteomics were used to investigate the mode of action of new antifungal agents (Mercer et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2012), to identify new targets (Bruneau et al., 2003; Kley, 2004; Hooshdaran et al., 2005; Delom et al., 2006; Rogers et al., 2006; Hoehamer et al., 2010), and to study the synergistic effects among compounds (Xu et al., 2009; Agarwal et al., 2012). This approach was also used to investigate the clinical action of antifungals and new drugs against Paracoccidioides spp. (Zambuzzi-Carvalho et al., 2013; Neto et al., 2014).

The study aimed to investigate the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of argentilactone, as well as, the proteomic profile of P. lutzii after incubation with argentilactone. In addition, the work aimed to evaluate the lipids and glucose levels, and in vivo methylcitrate dehydrogenase transcript level in P. lutzii.

Experimental

Extraction of (R)-argentilactone (2H-pyran-2-one, 6-(1-heptenyl)-5,6-dihydro-,[r-(z)])

The essential oil of H. ovalifolia was obtained as described previously and the NMR data are consistent with the literature (Oliveira et al., 2004).

Reduction of 3-(4,5- dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) method

The MTT colorimetric method described by Mosmann (1983) was used to evaluation of the cell viability after treatment with 9, 18, 36, and 72 μg/mL argentilactone. The cell viability was measured by the mitochondrial dehydrogenase enzyme activity of living cells. Human lung fibroblast normal cell line (MRC5; CCL-171) used in this study were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection—ATCC, Rockville, Maryland. For the MTT assay, 1 × 104 cells were seeded in 96 well microtiter plates in the absence or presence of argentilactone and incubated at 37°C at atmospheric pressure containing 5% CO2. After incubation for 24 h, 10 μL MTT (5 mg/mL) was added to the cells, and following 4 h of incubation with MTT, 200 μL PBS/20% SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate) was added. A quantification of optical density was measured using a spectrophotometer (Awareness Technology, Palm City, Florida). The percentage of cell viability was calculated by GraphPad Prism 4.02 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California).

Comet assay

The effect genotoxic of argentilactone was examined by comet assay according to Singh et al. (1988). Argentilactone was added at concentrations of 9, 18, 36, and 72 μg/mL to 1 × 105 MRC5 cells and was incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, 15 μL of the cells was added to 100 μL of a low melting point agarose (0.5%), spread onto microscope glass slides pre-coated with a normal melting point agarose (1.5%), and covered with a coverslip. The slides were incubated for 15 min at 4°C and after were immersed in cold lysis solution (2.4 M NaCl; 100 mM EDTA; 10 mM Tris, 10% dimethylsulfoxide, and 1% Triton-X, pH 10) for 24 h. After lysis, the slides were subjected to electrophoresis for 25 min at 25 V and 300 mA. Thereafter, the slides were neutralized for 15 min in buffer 0.4 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, dried at room temperature and fixed in 100% ethanol for 5 min. The slides were stained using 20 μg/mL ethidium bromide. Two slides were prepared for MRC5, and 50 cells were screened per sample using a fluorescence microscope interfaced with a computer. Analysis of the nucleoids was performed in software Comet Score 15 according to the migration of the fragments, as previously described (Kobayashi et al., 1995). The damage index was calculated according to Tice et al. (2000).

P. lutzii and culture conditions

P. lutzii (ATCC-MYA-826) has been extensively studied in different laboratories (Pereira et al., 2010; Cruz et al., 2011; Oliveira et al., 2013; Teixeira et al., 2013). The fungus was cultivated in Fava-Netto's medium (1.0% w/v peptone, 0.5% w/v yeast extract, 0.3% w/v proteose peptone, 0.5% w/v beef extract, 0.5% w/v NaCl, 4% w/v glucose, and 1.4% w/v agar, pH 7.2) (Fava-Netto and Raphael, 1961) at 36°C for growth of the yeast phase.

Culture and cell viability

P. lutzii yeast cells were sub-cultured for 1 week in solid Fava-Netto's medium at 36°C. For viability experiments, yeast cells were cultured in a liquid chemically defined medium McVeigh Morton (MMcM) (Restrepo and Jiménez, 1980) in the absence or presence of a sub-inhibitory concentration of 9 μg/mL argentilactone (Prado et al., 2014) at 36°C. Aliquots were collected after 0, 6, 8, 10, and 12 h of incubation. The cell viability was determined by counting stained cells in a Neubauer chamber using trypan blue, based on the principle that live cells with intact cellular membranes expelled the dye (Strober, 2001). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Preparation of protein extracts

P. lutzii yeast cells were collected after 10 h of contact with 9 μg/mL argentilactone and the total proteins were extracted. Centrifugation of the cells was performed at 10,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and disrupted by glass beads. The extraction buffer (20 mM Tris- HCl pH 8.8; 2 mM CaCl2) added of a mixture of protease inhibitors (serine, cysteine and calpain inhibitors) (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) was added to the yeast cells. After the addition of glass beads (0.45 mm), the cells were vigorously mixed for 1 h at 4°C, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 15 min at the same temperature. The supernatant was collected, and the protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford reagent (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri). The samples were stored in aliquots at 80°C.

Protein digestion and label free quantitative nanoUPLC-MSEproteomics

Equimolar amount of three biological replicates were pooled were pooled and submitted to the proteomic analysis. A total of 300 μg of each sample in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate was submitted to tryptic digestion. First, 25 μL of the surfactant RapiGEST™ (0.2% v/v) (Waters Corp, Milford, Massachusetts) was added and then incubated at 80°C for 15 min. The protein samples were reduced with 2.5 μL of a 100 mM DTT solution for 30 min at 60°C; and then alkylated with 2.5 μL of 300 mM iodoacetamide in the dark for 30 min. After, 10 μL of 50 ng/μL (in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate) trypsin solution (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) was added. The sample was digested at 37°C overnight. Following the digestion, RapiGEST™ was hydrolyzed with 10 μL of 5% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid at 37°C for 90 min. The sample was centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4°C for 30 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a Total Recovery vial (Waters Corp). The digests were dried and the peptides were resuspended in 20 mM ammonium formate pH 10. The obtained peptides were further separated by RP-RP-HPLC using a nanoACQUITY™ system (Waters Corp), as described before (Geromanos et al., 2009). Each sample was run in three technical replicates. The column loads were 5 μg of protein digests for the analysis of samples in triplicate. First, the samples were separated in 5 fractions in the mobile phase at pH 10. Each fraction was further separated by reverse phase chromatography with a mobile phase at pH 2.5. Label-free data-independent scanning (MSE) experiments were performed with a Synapt HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters, Manchester, UK), which switched between low collision energy MS (3 eV) and elevated collision energies MSE (12–40 eV) applied to the trap “T-wave” CID cell with argon gas (Curty et al., 2014).

The protein identifications and quantitative packaging were generated using specific algorithms (Silva et al., 2005, 2006) and search was performed against a P. lutzii specific database. The ProteinLynx Global server v.2.5.2 (PLGS) with ExpressionE informatics v.2.5.2 was used to proper spectral processing, database searching conditions and quantitative comparisons. The database was randomized to access the false-positive rate of identification (4%). Trypsin was the primary digest reagent, allowing for 1 missed cleavage. Carbamidomethyl-C was specified as fixed modification and phosphorylation STY and oxidation M were used as variable modifications. The minimum fragment ion matches per peptide, the minimum fragment ion matches per protein, and the minimum peptide matches per protein were, respectively set as 2.5 and 1. It was used 50 ppm as mass variation tolerance. A protein detected in all replicates presenting a variance coefficient less than 10% was used to normalize the expression data to compare the protein levels between control and argentilactone-treated conditions. The confidence interval of 95% was used. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (Vizcaíno et al., 2014) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD002285.

Cell culture and macrophage infection assay

The J774 A1 macrophage cells were cultured in 75 m2 flasks and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 in an RPMI medium (RPMI 1640, Vitrocell, São Paulo, São Paulo) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum. The J774 macrophage cells were plated at 5 × 105 cells per well on 6-well culture plates and infected with P. lutzii yeast cells at a 1:5 ratio macrophage:yeast. The cells were co-cultivated for 12 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 to allow for fungi adhesion and/or internalization. After this, the treatment with 9 μg/mL argentilactone and controls in the absence of argentilactone and presence of sulfametoxazole were conducted.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real time reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

The samples of P. lutzii infected macrophages in the presence of 9 μg/mL argentilactone and 0.01 mg/mL sulfametoxazole (control) were washed three times with sterile water. After centrifugation, the pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen. The cells were disrupted with glass beads for 10 min in the presence of Trizol reagent (Invitrogen™, Carlsbad, California) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNAs were obtained using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and an oligo (dT)15primer. The qRT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicates of three independent experiments using a StepOnePlus™ RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). The SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) was used as the reaction mixture, with 10 pmol of each primer and 40 ng of template cDNA at a final volume of 25 μL. A melting curve analysis and electrophoresis were performed to confirm a single PCR product. The qRT-PCR thermal cycling consisted of 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Constitutively expressed alpha tubulin (sense: GAGCGATTCATTGGAGGGATT; anti-sense: ATCAGGGAAAACAGAGTAAGTC) (Zambuzzi-Carvalho et al., 2013) was selected to normalize the samples. A non-template control was included to eliminate contamination or non-specific reactions. The standard curve was generated from a pool of cDNA from each sample. The standard cDNA was serially diluted in a ratio of 1:5. The relative expression levels of selected genes were calculated using the standard curve method for relative quantification (Bookout et al., 2006). The oligonucleotides used in the qRT-PCR analyses are relatives to the methylcitrate dehydrogenase gene (sense: CAACTCTGACCTTGCATTTGAT; anti-sense: GATGTTGAAAGCACCGTTGAC). The experiments were performed in triplicate. A Student's t-test was performed to analyze significant differences between the different samples and a p-value p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Dosage of glucose

The concentration of glucose was determined following the instructions of the enzymatic glucose kit (Doles Ltda, Goiânia, Goiás). A total of 1 × 105 cells was treated with 9 μg/mL of argentilactone by 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 24 h. The control cells were grown in the absence of argentilactone. Aliquots of 10 μL were collected in each time, adding 1 mL of color solution and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. The absorbance was measured by spectrophotometer at 510 nm.

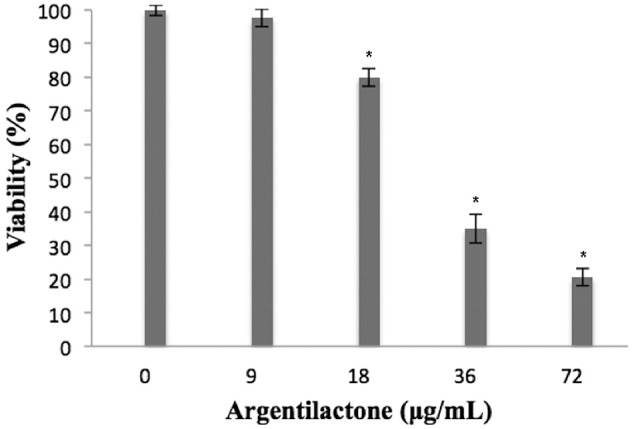

Determination of intracellular lipid content

Intracellular lipid content was determined by flow cytometry using lipophilic dye Nile Red. Aliquots were collected after 0, 6, 10, 12 and 24 h of incubation with 9 μg/mL of argentilactone and in the absence of the compound. The cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 2 μg/mL Nile red (Sigma Aldrich), for 15 min at room temperature. Nile red intracellular fluorescence was determined by guava easyCyte™ Flow Cytometers (Merck Millipore, Billerica, EUA) on emission channel of 585 nm and excitation 488 nm. A total of 5000 cells were collected to analysis.

Results and discussion

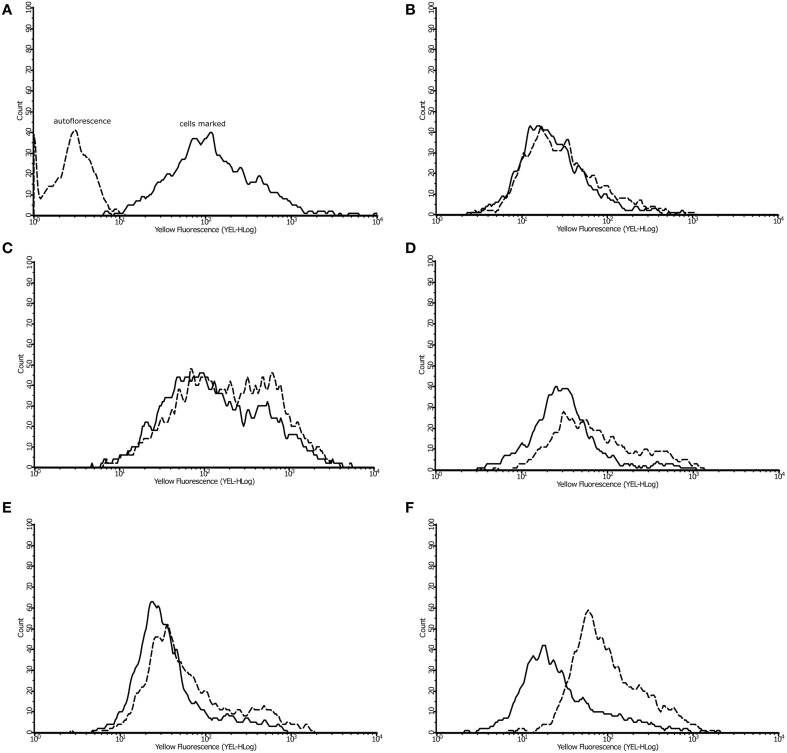

Evaluation of argentilactone cytotoxicity against human cells

The cytoxicity of argentilactone was evaluated for human cells MRC5 (Figure 1). The data show a dose-dependent relationship between the number of dead cells and argentilactone concentration. The concentration of 9 μg/mL argentilactone did not promote cell cytotoxicity for MRC5. For the MRC5 cells, the IC50 was 32 μg/mL. For the P. lutzii yeast cells, the IC50 was 18 μg/mL (Prado et al., 2014). These data suggest that the argentilactone is more toxic to the fungus than for human cells.

Figure 1.

Percentage of viable MRC5 normal human cells after exposure to different concentrations of argentilactone. Significance was accepted *p < 0.05. Analysis was performed by a One-Way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-test.

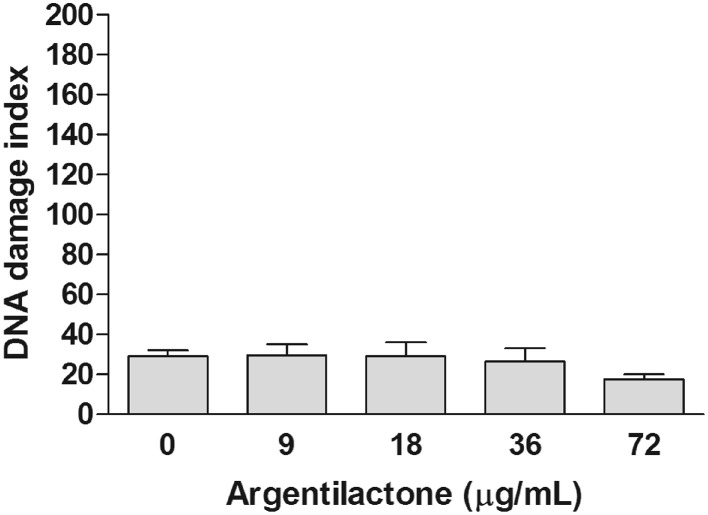

Aiming to evaluate if argentilactone induces DNA damage in human cells, the comet assay was performed to MRC5 cells treated with different concentrations of this compound. This assay has achieved the status of a standard test in the battery of tests used to assess the safety of novel pharmaceuticals or other chemicals and is now well-established as a sensitive assay for detecting strand breaks in the DNA of single cells (Fairbairn et al., 1995). Figure 2 shows the effect of argentilactone in MRC5 cells. In the MRC5 normal cells the compound did not induce DNA damage when compared to the negative control (p > 0.05). The data above suggest that this compound is safe to human.

Figure 2.

Effect of argentilactone on the induction of MRC5 cells DNA damage. Cells were treated with 9, 18, 36, and 72 μg argentilactone for 24 h and analyzed by comet assay. Analysis was performed by a One-Way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-test.

Determination of incubation time with argentilactone

Metabolic response and survival strategies of P. lutzii were discussed at the molecular level using genomic and proteomic approaches (Desjardins et al., 2011; Weber et al., 2012; Grossklaus et al., 2013; Zambuzzi-Carvalho et al., 2013). In this study, we investigated the response of P. lutzii to the antifungal prototype argentilactone.

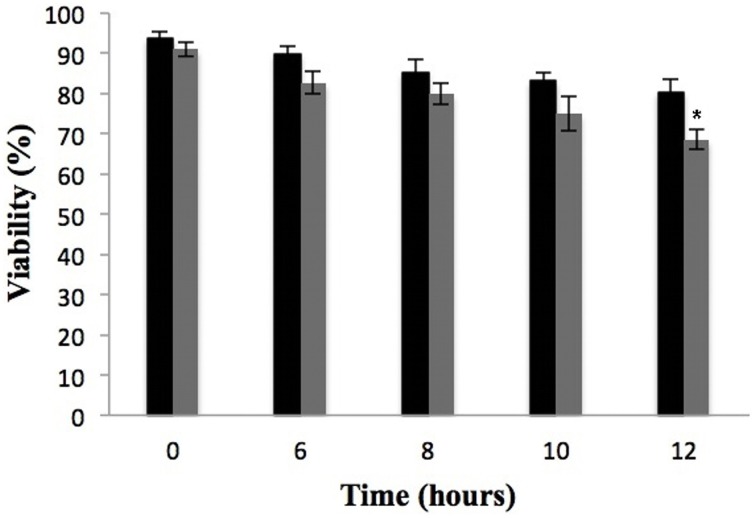

A viability curve of P. lutzii yeast cells was constructed at time 0, 6, 8, 10, and 12 h in the presence of a sub-inhibitory concentration of 9 μg/mL argentilactone aiming to determine the time point to be used for the proteomic experiments. The time of 10 h with a cell viability of 90% (Figure 3) was chosen for proteomic studies.

Figure 3.

Effect of argentilactone on P. lutzii cells growth. Yeast cells were cultured at 36°C in the absence (black) and presence (gray) of 9 μg/mL argentilactone for 12 h. Aliquots were taken and the cells were counted in a Neubauer chamber. *p < 0.05.

Proteomic response of P. lutzii upon exposure to argentilactone

A nanoUPLC-MSE-based proteomics approach was employed to identify the P. lutzii yeast cell differentially regulated proteins in response to argentilactone. A total of 211 proteins were identified of which 155 had significant regulation at a 1.2-fold change or more. This cut off ratio was used in order to identify broader cellular processes regulated by the compound instead to focus in specifically regulated proteins. From these, 32 were more abundant, 88 less abundant, 20 detected only in treated cells and 15 detected only in the control. A total of 7% of the proteins had no predicted function; the other 93% were classified in functional categories using the FunCat2 system. The regulated proteins were clustered in proteins with increased expression after incubation with argentilactone (Table 1) and proteins with decreased expression after incubation with argentilactone (Table 2).

Table 1.

P. lutzii more abundant proteins after incubation with argentilactone.

| Functional categorya | Protein description | Accession numberb | Protein score | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| METABOLISM | ||||

| Amino acid metabolism | 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase | PAAG_05253 | 1803.48 | 1.768 |

| 4-aminobutyrate aminotransferase | PAAG_00468 | 1503.69 | 1.804 | |

| Homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase | PAAG_08164 | 739.59 | 1.878 | |

| Methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | PAAG_07036 | 1184.68 | 1.336 | |

| O-acetylhomoserine (Thiol)-lyase | PAAG_08100 | 3986.80 | 1.323 | |

| Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | PAAG_08512 | 1347.52 | 1.221 | |

| Pyruvate decarboxylase | PAAG_02050 | 1361.75 | 1.323 | |

| Sulfite oxidase | PAAG_07811 | 1481.90 | 1.221 | |

| Aminopeptidase B | PAAG_09004 | 450.66 | * | |

| Aspartyl aminopeptidase | PAAG_04205 | 526.39 | * | |

| Aspartyl aminopeptidase | PAAG_00664 | 568.78 | * | |

| Cysteine synthase | PAAG_07813 | 412.94 | * | |

| Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA lyase | PAAG_06215 | 1087.40 | * | |

| Formate dehydrogenase-III | PAAG_03599 | 1012.38 | * | |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | Triosephosphate isomerase | PAAG_02585 | 10825.00 | 1.246 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex component Pdx1 | PAAG_00666 | 997.13 | 1.768 | |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex | PAAG_00050 | 877.32 | 1.616 | |

| Fumarate reductase Osm1 | PAAG_04851 | 2013.07 | 1.234 | |

| 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase | PAAG_07875 | 4971.33 | 1.568 | |

| N-acetylglucosamine-phosphate mutase | PAAG_01931 | 398.11 | * | |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase | PAAG_05392 | 399.42 | * | |

| Fumarylacetoacetase | PAAG_08163 | 2404.04 | 1.234 | |

| Nitrogen metabolism | Formamidase | PAAG_03333 | 1620.07 | 1.209 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | Rad4 family protein | PAAG_05019 | 2058.26 | 1.377 |

| Coenzyme metabolism | Riboflavin synthase subunit alpha | PAAG_01934 | 554.30 | * |

| Cell rescue, defense and virulence | Proteasome component C5 | PAAG_00866 | 1414.16 | * |

| Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] | PAAG_04164 | 2348.64 | 1.297 | |

| Sulfur metabolite repression control protein C | PAAG_07339 | 4835.50 | * | |

| ENERGY | ||||

| Eletron transport | Cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide VI | PAAG_07246 | 2376.00 | 1.477 |

| Cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide IV | PAAG_06796 | 711.90 | ||

| Associate energy conservation | Cytochrome c PriAC=F2TJX0 | PAAG_06268 | 1307.21 | 1.522 |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | 6-phosphogluconolactonase | PAAG_05621 | 688.50 | 1.297 |

| Glyoxylate cycle | Malate synthase | PAAG_04542 | 617.40 | * |

| Krebs cycle | Succinyl-CoA: | PAAG_05093 | 770.38 | * |

| Methyl citrate cycle | 2-methylcitrate dehydratase | PAAG_04559 | 20407.15 | 1.297 |

| Oxidation of fatty acids | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | PAAG_06309 | 3244.11 | 1.716 |

| Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | PAAG_03447 | 1578.04 | * | |

| Peroxisomal 3-ketoacyl-coA thiolase | PAAG_03689 | 1248.76 | * | |

| Siderophore-iron transport | Siderophore peptide synthase | PAAG_02354 | 1582.68 | * |

| Protein fate | Chaperone DnaK | PAAG_01339 | 14261.80 | 1.259 |

| Chaperonin | PAAG_05142 | 71219.03 | 1.584 | |

| Chaperonin GroL | PAAG_08059 | 36257.80 | 1.336 | |

| GrpE protein homolog | PAAG_06255 | 6685.85 | 1.649 | |

| Glutathione S-transferase | PAAG_08162 | 766.51 | 1.405 | |

| Peptidylprolyl isomerase | PAAG_05788 | 3381.68 | 1.284 | |

| CORD and CS domain-containing protein | PAAG_02973 | 1899.14 | * | |

| Miscellaneous | Thiol methyltransferase | PAAG_06955 | 1027.93 | 1.391 |

| Translation | Endoribonuclease L-PSP | PAAG_08313 | 12115.91 | 1.234 |

| Unclassified | Uncharacterized protein | PAAG_00297 | 870.53 | 1.649 |

| Uncharacterized protein | PAAG_07772 | 1786.94 | 1.209 | |

Functional category—based on the MIPS Functional categories database and GO.

Accession number—accession number of matched protein from Paracoccidioides database (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/paracoccidioides_brasiliensis/MultiHome.html).

Proteins detected only during incubation with argentilactone.

Table 2.

P. lutzii less abundant proteins after incubation with argentilactone.

| Functional categorya | Protein description | Accession numberb | Protein score | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| METABOLISM | ||||

| Amino acid metabolism | Acetolactate synthase | PAAG_00221 | 849.43 | 0.726 |

| Argininosuccinate synthase | PAAG_07114 | 6934.38 | 0.522 | |

| Cobalamin-independent methionine synthase MetH/D | PAAG_07626 | 2518.10 | 0.577 | |

| Isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial | PAAG_04102 | 953.65 | 0.811 | |

| NADP-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | PAAG_07689 | 1723.70 | 0.600 | |

| Ornithine aminotransferase | PAAG_06431 | 1262.54 | 0.684 | |

| Lysine decarboxylase-like protein | PAAG_03537 | 800.11 | * | |

| NAD-specific glutamate dehydrogenase | PAAG_01002 | 1969.33 | * | |

| Saccharopine dehydrogenase | PAAG_02693 | 1249.65 | * | |

| Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | PAAG_07412 | 4659.48 | 0.677 | |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | Mannitol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase | PAAG_06473 | 4920.79 | 0.726 |

| Eukaryotic phosphomannomutase | PAAG_00889 | 1400.74 | 0.691 | |

| GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase A | PAAG_08174 | 860.91 | * | |

| Transketolase TktA | PAAG_04444 | 2581.21 | 0.763 | |

| Coenzyme metabolism | Adenosylhomocysteinase | PAAG_02859 | 14585.17 | 0.440 |

| Dihydropteroate synthase | PAAG_01324 | 870.83 | 0.779 | |

| Pyridoxine biosynthesis protein pyroA | PAAG_07321 | 2354.97 | 0.787 | |

| S-adenosylmethionine synthase | PAAG_02901 | 6069.65 | 0.357 | |

| Nucleotide metabolism | Bifunctional purine biosynthesis protein ADE17 | PAAG_00731 | 4517.89 | 0.811 |

| Adenylosuccinate lyase | PAAG_04974 | 686.76 | * | |

| S-methyl-5-thioadenosine phosphorylase | PAAG_01302 | 1274.52 | * | |

| UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase | PAAG_06885 | 768.34 | 0.779 | |

| Phosphate metabolism | Inorganic pyrophosphatase | PAAG_00657 | 4020.00 | 0.771 |

| Cell cycle and dna processing | Cell division cycle protein 48 | PAAG_05518 | 1782.70 | 0.719 |

| D-tyrosyl-tRNA(Tyr) deacylase | PAAG_03334 | 22078.91 | 0.741 | |

| Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha | PAAG_04571 | 4281.41 | 0.779 | |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | PAAG_06168 | 2417.21 | 0.795 | |

| Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | PAAG_00923 | 5676.48 | 0.748 | |

| TCTP family protein | PAAG_09083 | 23693.70 | 0.463 | |

| Thioredoxin | PAAG_02364 | 25560.74 | 0.719 | |

| UV excision repair protein Rad23 | PAAG_04949 | 1953.93 | 0.651 | |

| Cell rescue, defense and virulence | Heat shock protein 30 | PAAG_00871 | 6591.33 | 0.492 |

| Heat shock protein 88 | PAAG_07750 | 15855.80 | 0.811 | |

| Heat shock protein SSB | PAAG_07775 | 5550.62 | 0.487 | |

| ENERGY | ||||

| Eletron transport and membran associate energy conservation | ATP synthase D chain, mitochondrial | PAAG_04570 | 1983.65 | 0.748 |

| ATP synthase gamma chain | PAAG_05576 | 4554.87 | 0.595 | |

| ATP synthase subunit alpha | PAAG_04820 | 17850.35 | 0.670 | |

| ATP synthase subunit beta | PAAG_08037 | 19311.82 | 0.726 | |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase AcuF | PAAG_08203 | 2953.75 | 0.554 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit | PAAG_08295 | 904.41 | 0.748 | |

| Glucokinase glkA | PAAG_06172 | 746.76 | * | |

| Phosphoglucomutase | PAAG_02011 | 2057.00 | 0.482 | |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | PAAG_02869 | 3428.25 | 0.619 | |

| Pyruvate kinase | PAAG_06380 | 9829.55 | 0.657 | |

| Enolase | PAAG_00771 | 39472.25 | 0.779 | |

| Phosphofructokinase subunit | PAAG_01583 | 587.46 | * | |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component beta subunit | PAAG_01534 | 2794.88 | 0.733 | |

| Glyoxylate cycle | Isocitrate lyase | PAAG_04549 | 923.71 | 0.827 |

| Krebs cycle | Malate dehydrogenase | PAAG_00053 | 47991.24 | 0.795 |

| Malate dehydrogenase | PAAG_08449 | 7490.87 | 0.756 | |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase subunit 1 | PAAG_00856 | 1820.37 | * | |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase subunit 2 | PAAG_07729 | 1604.29 | * | |

| Succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial | PAAG_01725 | 1798.19 | 0.827 | |

| Oxidation of fatty acids | Short-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | PAAG_05454 | 1028.15 | * |

| Transport | Carbonic anhydrase | PAAG_05716 | 854.25 | 0.795 |

| Clathrin light chain | PAAG_08252 | 1049.51 | 0.741 | |

| GTP-binding nuclear protein ran-1 | PAAG_04651 | 3676.19 | 0.527 | |

| Nipsnap family protein | PAAG_05960 | 4593.91 | 0.677 | |

| Vesicular-fusion protein sec17 | PAAG_06233 | 559.70 | * | |

| Rab GDP-dissociation inhibitor | PAAG_06344 | 1958.40 | 0.625 | |

| Protein fate | G-protein comlpex beta subunit CpcB | PAAG_06996 | 2600.70 | 0.741 |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase | PAAG_00986 | 14896.18 | 0.670 | |

| Miscellaneous | Thiol-specific antioxidant | PAAG_03216 | 4271.92 | 0.427 |

| Translation | Cytosolic large ribosomal subunit protein L30 | PAAG_01050 | 6746.86 | 0.756 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S0 | PAAG_02111 | 10467.63 | 0.741 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S11 | PAAG_06367 | 3129.84 | 0.512 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S14 | PAAG_01433 | 1642.34 | 0.712 | |

| 40s ribosomal protein s15 | PAAG_04690 | 6547.01 | 0.625 | |

| 40s ribosomal protein s26 | PAAG_07847 | 9205.88 | 0.477 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S5 | PAAG_05484 | 5524.47 | 0.625 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S7 | PAAG_07182 | 7212.75 | 0.670 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S8 | PAAG_00264 | 3915.07 | 0.651 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S9 | PAAG_01435 | 2407.07 | 0.487 | |

| 40S ribosomal protein S9 | PAAG_03828 | 2402.26 | 0.502 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L13 | PAAG_06320 | 5338.78 | 0.589 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L15 | PAAG_00969 | 4623.56 | 0.468 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L18A | PAAG_00952 | 3245.52 | 0.571 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L2 | PAAG_00430 | 2292.83 | 0.517 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L43 | PAAG_06569 | 12650.10 | 0.543 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L4-A | PAAG_08888 | 5405.80 | 0.619 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L5 | PAAG_00548 | 911.54 | 0.795 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L7 | PAAG_06487 | 3961.73 | 0.748 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein | PAAG_01834 | 4195.17 | 0.538 | |

| 60S ribosomal protein L31E | PAAG_04965 | 2514.61 | * | |

| Ribosomal protein S23 | PAAG_00385 | 923.83 | * | |

| Elongation factor 1-alpha | PAAG_02024 | 13081.64 | 0.284 | |

| Elongation factor 1-beta | PAAG_03028 | 26825.63 | 0.427 | |

| Elongation factor 1-gamma | PAAG_03556 | 9096.78 | 0.317 | |

| Elongation factor 2 | PAAG_00594 | 11304.17 | 0.403 | |

| Polyadenylate-binding protein | PAAG_00244 | 1647.87 | 0.631 | |

| Ribosomal protein L19 | PAAG_08497 | 3909.55 | 0.607 | |

| Ribosomal protein P0 | PAAG_00801 | 2669.74 | 0.560 | |

| Ribosomal protein S20 | PAAG_03322 | 1872.13 | 0.763 | |

| Ribosomal protein S6 | PAAG_02634 | 1918.03 | 0.589 | |

| 40S Ribosomal protein S3 | PAAG_01785 | 6921.45 | 0.595 | |

| U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein component | PAAG_07785 | 372.29 | 0.242 | |

| Unclassified | Hypothetical protein | PAAG_07955 | 2234.10 | 0.507 |

| Uncharacterized protein | PAAG_07989 | 907.76 | 0.657 | |

| Uncharacterized protein | PAAG_04274 | 841.04 | 0.726 | |

| Uncharacterized protein | PAAG_02434 | 1488.40 | * | |

| Uncharacterized protein | PAAG_07841 | 11750.10 | 0.458 | |

| Uncharacterized protein | PAAG_00724 | 3895.92 | 0.492 | |

Functional category—based on the MIPS Functional categories database and GO.

Accession number—accession number of matched protein from Paracoccidioides database (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/paracoccidioides_brasiliensis/MultiHome.html).

Proteins detected only in control conditions.

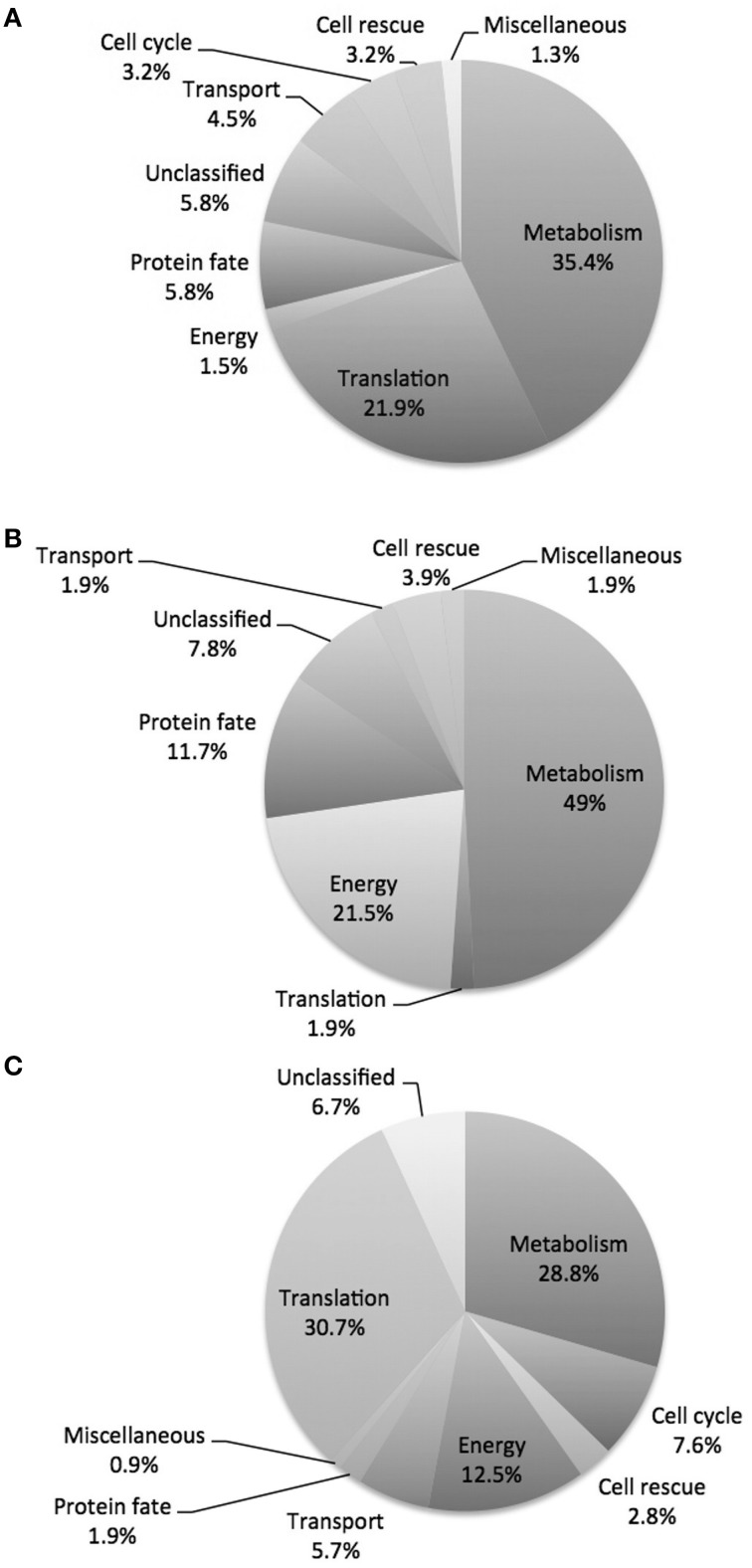

The proteomic analysis, including all regulated proteins, showed proteins associated with metabolism 35.4%, translation 21.9%, protein fate 5.8%, unclassified 5.8%, transport 4.5%, cell cycle 3.2%, cell rescue 3.2%, energy 1.5% and miscellaneous 1.3% (Figure 4A; Tables 1, 2). The proteome analysis that included up-regulation and proteins exclusive to the presence of argentilactone showed proteins associated with metabolism 49%, energy 21.5%, protein fate 11.7%, unclassified 7.8%, cell rescue 3.9%, transport 1.9%, translation 1.9% and miscellaneous 1.9% (Figure 4B; Table 1). The proteome analysis that included down-regulation and proteins exclusive to the control condition showed proteins associated with translation 30.7%, metabolism 28.8%, energy 12.5%, cell cycle 7.6%, unclassified 6.7%, transport 5.7%, cell rescue 2.8%, protein fate 1.9% and miscellaneous 0.9% (Figure 4C; Table 2).

Figure 4.

Diagram depicting the breakdown of P. lutzii proteins. (A) Proteins differentially expressed in the absence and presence of argentilactone; (B) More abundant proteins in the presence of argentilactone; (C) Less abundant proteins in the absence of argentilactone.

The proteins involved in cell rescue, defense, and virulence confer protection to the cell and assure survival upon various stresses. Molecular chaperones are very conserved and has the function related to maintenance of conformational equilibrium of proteins (Hartl, 1996). In this study, as could be expected, were identified stress-related proteins regulated in the presence of argentilactone (Tables 1, 2). In addition to the heat shock proteins, proteasome component C5 and sulfur metabolite repression control protein C were exclusive to P. lutzii exposed to argentilactone. This result could indicate the involvement of these proteins in protecting the fungus from the stress generated by argentilactone.

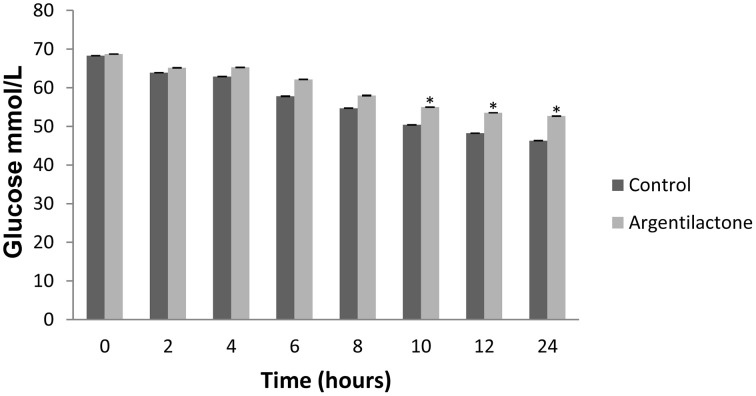

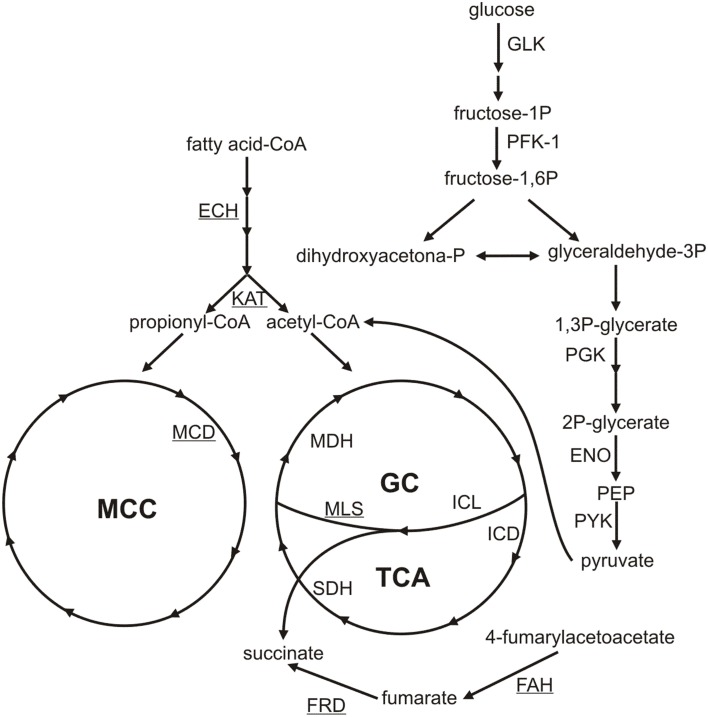

Our proteomic analyses indicate a global reorganization of P. lutzii carbohydrate metabolism during the exposure to argentilactone. One change detected here is the decrease of several enzymes of glycolytic pathway such as enolase, phosphoglucomutase, phosphoglycerate kinase, pyruvate kinase, and those exclusive to the absence of argentilactone as glucokinase and phosphofructokinase (Table 2). The down-regulation of succinate dehydrogenase, two malate dehydrogenases, and isocitrate dehydrogenase subunits 1 and 2 (Table 2), shows that Krebs cycle is not completely functioning in P. lutzii. In the presence of argentilactone, P. lutzii decreased the glucose consume (Figure 5), suggesting that glycolysis is partially blocked. In addition, the gluconeogenesis is also not completely functioning, as phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase is less abundant (Table 2). Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase plays an importantl role in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis, sinceit is essential for Mycobacterium tuberculosis during mouse infection. M. tuberculosis utilizes primarily gluconeogenic substrates for in vivo persistence, suggesting that this enzyme represents a target for treatments (Marrero et al., 2010).

Figure 5.

Glucose quantification. The level of glucose was quantified by enzymatic kit after 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 24 h. The control was performed with cells in the absence of argentilactone. The Student's t-test was used for statistical comparisons, and the observed differences were statistically significant (*p ≤ 0.05).

The glyoxylate cycle is not completely functioning in the presence of argentilactone as the enzyme isocitrate lyase is less abundant (Table 2). This finding is consistent with our previous results showing that the P. lutzii isocitrate lyase recombinant and native forms were inhibited in the presence of argentilactone (Prado et al., 2014). On the other hand, malate synthase is more abundant. Under the absence of six-carbon elements, the glyoxylate cycle is induced (Fernandez et al., 1993). The glyoxylate pathway is important in the generations of C4 dicarboxylic acids from acetyl-CoA units, bypassing the decarboxylation steps in the TCA cycle. The cycle is important to fungal pathogenesis. For example, many of the genes highly induced in phagocytized C. albicans were members of the glyoxylate cycle (Lorenz and Fink, 2001; Lorenz et al., 2004). The C. albicans isocitrate lyase gene is essential for gluconeogenic carbon source utilization and starvation rather than a marker for lipid metabolism (Brock, 2009; Otzen et al., 2013).

The methylcitrate cycle is an alternative route of carbon through pyruvate production (Bramer et al., 2002) and an important pathway for propionyl-CoA metabolism is the methylcitrate pathway. The 2-methylcitrate dehydratase that participates in the methylcitrate cycle is more abundant (Table 1). In addition, methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase that produces propionyl-CoA seems to lead to the production of pyruvate (Table 1). Pyruvate produces acetaldehyde from the action of pyruvate decarboxylase that is more abundant in the presence of argentilactone (Table 1). Up-regulation of o-acetylhomoserine (thiol)-lyase leads to the production of L-methionine and acetate. Acetate is converted to acetoacetyl-CoA by the action of acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, which was only detected during the treatment with argentilactone (Table 1).

The β-oxidation is a pathway for the utilization of fatty acids (Poirier et al., 2006) in which the 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolases enzymes are so important (Otzen et al., 2013). The enzymes 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, which was only detected in P. lutzii exposed to argentilactone, and enoyl-CoA hydratase from β-oxidation were also more abundant (Table 1). The lipids content from P. lutzzi was decreased in the presence of argentilactone mainly after 24 h (Figure 6) reinforcing the importance of the β-oxidation and methylcitrate cycle for P. lutzzi responding to argentilactone.

Figure 6.

Effect of argentilactone on intracellular lipid content of P. lutzzi. The presence of lipids was determined by flow cytometry. Cells was stained with dye Nile Red (A). The analysis of yeast cells in presence and absence of argentilactone for (B) 0 h, (C) 6 h, (D) 10 h, (E) 12 h, and (F) 24 h was performed. Line histograms represent the cells treated with argentilactone and dotted histograms represent control cells without treatment.

Glyoxylate is not produced from isocitrate because isocitrate lyase is less abundant in the presence of argentilactone. The high production of succinate is indicated by up-regulation of fumarylacetoacetase, which uses 4-fumarylacetoacetate to produce fumarate, and then fumarate reductase uses fumarate to produce succinate (Table 1).

It is important to mention that argentilactone weakened the protein synthesis of P. lutzii. Translation was the functional category most affected with 33 less abundant proteins. In general, we could observe that energy-producing pathways, such as glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, and TCA, were less abundant in the presence of argentilactone. An overview of the metabolic changes of P. lutzii in presence of the compound is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Metabolic changes of P. lutzii yeast cells exposed to argentilactone. The less abundant proteins during treatment are not highlighted. The more abundant proteins are underlined. GC, glyoxylate cycle; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; MCC, methylcitrate cycle; GLK, glucokinase; PFK-1, phosphofructokinase-1; PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase; ENO, enolase; PYK, pyruvate kinase; ICL, isocitrate lyase; MLS, malate synthase; MDH, malate dehydrogenase; FAH, fumarylacetoacetase; FRD, fumarate reductase; ECH: enoyl-CoA-hydratase; KAT, acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; MCD, methylcitrate dehydrogenase.

Validation of nanoUPLC-MSE data

The innate immune cells like resident macrophages and dendritic cells are the first barriers of defense system that interact with Paracoccidioides spp. cells (Calich et al., 2008). It is known that the phagosome is poor in nutrients and was reported to not are a good environment as evidenced by the little quantities of glucose, other sugars, and amino acids (Lorenz et al., 2004; Fan et al., 2005; Tavares et al., 2007; Cooney and Klein, 2008; Silva et al., 2008).

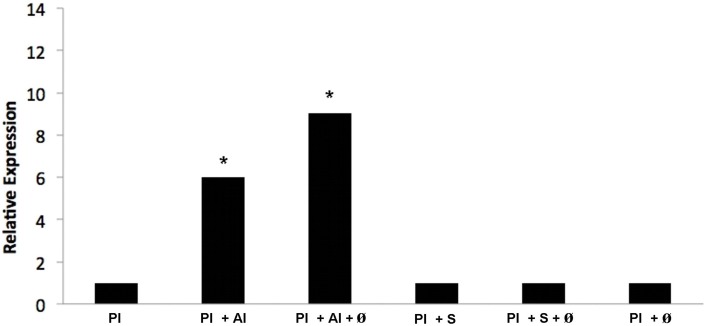

Methylcitrate dehydrogenase is an important enzyme of the methylcitrate cycle. Thus, aiming to verify whether the transcript is regulated in vivo when P. lutzii is exposed to argentilactone, the compound was added to the medium during J744 A.1 macrophage infection. The relative expression analysis of transcripts encoding methylcitrate dehydrogenase was performed using qRT-PCR. Figure 8 shows that genes encoding methylcitrate dehydrogenase were induced, corroborating the observations from proteomic data. This finding indicates that the methylcitrate cycle composes the response of yeast cells during macrophage infection and not only in vitro.

Figure 8.

Quantification of the mRNA expression of the methylcitrate dehydrogenase gene of P. lutzii infecting macrophage during exposure to argentilactone and sulfamethoxazole by quantitative qRT-PCR. (1) P. lutzii (Pl); (2) P. lutzii (Pl) + argentilactone (Al); (3) P. lutzii (Pl) + argentilactone (Al) + ø; (4) P. lutzii (Pl) + sulfamethoxazole (S); (5) P. lutzii (Pl) + sulfamethoxazole (S) + ø; (6) P. lutzii(Pl) + ø. Data were normalized to the tubulin transcript. Data were analyzed by a One-Way ANOVA and a Tukey's multiple comparison post-test. *p ≤ 0.05.

Conclusions

The global characterization of the proteomic profile of P. lutzii responding to argentilactone enabled the visualization of the metabolic adaptation of the fungus to drug exposure. Important metabolic pathways were regulated, explaining the strong action of the compound on fungus growth and viability. In this study, alternative metabolic pathways adopted by the fungi were elucidated and helped to elucidate the course of action of the compound studied.

Funding

This work performed at Universidade Federal de Goiás was supported by MCTI/CNPq (Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia/Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), FNDCT (Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), FAPEG (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Goiás), CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior), FINEP (Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos), and INCT-IF (Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia para Inovação Farmacêutica). Additionally, FSA and BRSN were supported by fellowship from CAPES.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Agarwal A. K., Tripathi S. K., Xu T., Jacob M. R., Li X. C., Clark A. M. (2012). Exploring the molecular basis of antifungal synergies using genome-wide approaches. Front. Microbiol. 3:115. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookout A. L., Cummins C. L., Mangelsdorf D. J., Pesola J. M., Kramer M. F. (2006). High- throughput real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 15, Unit 158. 10.1002/0471142727.mb1508s73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramer C. O., Silva L. F., Gomez J. G., Priefert H., Steinbuchel A. (2002). Identification of the 2-methylcitrate pathway involved in the catabolism of propionate in the polyhydroxyalkanoate-producing strain Burkholderia sacchari IPT101(T) and analysis of a mutant accumulating a copolyester with higher 3-hydroxyvalerate content. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 271–279. 10.1128/AEM.68.1.271-279.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock M. (2009). Fungal metabolism in host niches. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 371–376. 10.1016/j.mib.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummer E., Castaneda E., Restrepo A. (1993). Paracoccidioidomycosis: an update. Clin. Microbiol. 6, 89–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J. M., Maillet I., Tagat E., Legrand R., Supatto F., Fudali C., et al. (2003). Drug induced proteome changes in Candida albicans: comparison of the effect of beta (1,3) glucan synthase inhibitors and two triazoles, fluconazole and itraconazole. Proteomics 3, 325–336. 10.1002/pmic.200390046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calich V. L. G., Costa T. A., Felonato M., Arruda C., Bernardino S., Loures F. V., et al. (2008). Innate immunity to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection. Mycopathologia 165, 223–236. 10.1007/s11046-007-9048-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. N., Vuckovic D., Sleno L., Olsen J. B., Pogoutse O., Havugimana P., et al. (2012). Target identification by chromatographic co-elution: monitoring of drug-protein interactions without immobilization or chemical derivatization Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 7. 10.1074/mcp.M111.016642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney N. M., Klein B. S. (2008). Fungal adaptation to the mammalian host: it is a new world, after all. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 511–516. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz A. H., Brock M., Zambuzzi-Carvalho P. F., Santos-Silva L. K., Troian R. F., Góes A. M., et al. (2011). Phosphorylation is the major mechanism regulating isocitrate lyase activity in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis yeast cells. FEBS J. 278, 2318–2332. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curty N., Kubitschek-Barreira P. H., Neves G. W., Gomes D., Pizzatti L., Abdelhay E., et al. (2014). Discovering the infectome of human endothelial cells challenged with Aspergillus fumigatus applying a mass spectrometry label-free approach. J. Proteomics 97, 126–140. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delom F., Szponarski W., Sommerer N., Boyer J. C., Bruneau J. M., Rossignol M., et al. (2006). The plasma membrane proteome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its response to the antifungal calcofluor. Proteomics 6, 3029–3039. 10.1002/pmic.200500762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins C. A, Champion M. D., Holder J. W., Muszewska A., Goldberg J., Bailão A. M., et al. (2011). Comparative genomic analysis of human fungal pathogens causing paracoccidioidomycosis. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002345. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn D. W., Olive P. L., O'Neill K. L. (1995). The comet assay: comprehensive review. Mutat. Res. 339, 37–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Kraus P. R., Boily M. J., Heitman J. (2005). Cryptococcus neoformans gene expression during murine macrophage infection. Eukaryot Cell 4, 1420–1433. 10.1128/EC.4.8.1420-1433.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava-Netto C., Raphael A. A. (1961). Reação intradérmica com polissacarídeo do Paracaccidioides brasiliensis, na blastomicose sul-americana. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. 4, 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E., Fernandez M., Moreno F., Rodicio R. (1993). Transcriptional regulation of the isocitrate lyase encoding gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS 333, 238–242. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80661-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco M. (1987). Host-parasite relationship in paracoccidioidomycosis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 25, 5–18. 10.1080/02681218780000021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geromanos S. J., Vissers J. P., Silva J. C., Dorschel C. A., Li G. Z., Gorenstein M. V., et al. (2009). The detection, correlation, and comparison of peptide precursor and product ions from data independent LC-MS with data dependent LC-MS/MS. Proteomics 9, 1683–1695. 10.1002/pmic.200800562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossklaus D. A., Bailão A. M., Vieira Rezende T. C., Borges C. L., de Oliveira M. A., Parente J. A., et al. (2013). Response to oxidative stress in Paracoccidioides yeast cells as determined by proteomic analysis. Microbes Infect. 5, 347–364. 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn R. C., Morato Conceição Y. T., Santos N. L., Ferreira J. F., Hamdan J. S. (2003). Disseminated paracoccidioidomycosis: correlation between clinical and in vitro resistance to ketoconazole and trimethoprim sulphamethoxazole. Mycoses 46, 342–347. 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00901.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F. U. (1996). Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature 381, 571–579. 10.1038/381571a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehamer C. F., Cummings E. D., Hilliard G. M., Rogers P. D. (2010). Changes in the proteome of Candida albicans in response to azole, polyene, and echinocandin antifungal agentes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 54, 1655–1664. 10.1128/AAC.00756-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooshdaran M. Z., Hilliard G. M., Rogers P. D. (2005). Application of proteomic analysis to the study of azole antifungal resistance in Candida albicans. Methods Mol. Med. 118, 57–70. 10.1385/1-59259-943-5:057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johann S., Rosa L. H., Rosa C. A., Perez P., Cisalpino P. S., Zani C. L., et al. (2012). Antifungal activity of altenusin isolated from the endophytic fungus Alternaria sp. against the pathogenic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 29, 205–209. 10.1016/j.riam.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kley N. (2004). Chemical dimerizers and three-hybrid systems: scanning the proteome for targets of organic small molecules. Chem. Biol. 11, 599–608. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H., Sugiyama C., Morikawa Y., Hayashi M., Sofuni T. (1995). A comparison between manual microscopic analysis and computerized image analysis in the single cell gel electrophoresis assay. MMS Commun. 3, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz M. C., Bender J. A., Fink G. R. (2004). Transcriptional response of Candida albicans upon internalization by macrophages. Eukaryot Cell. 3, 1076–1087. 10.1128/EC.3.5.1076-1087.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz M. C., Fink G. R. (2001). The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature 412, 83–86. 10.1038/35083594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero J., Rhee K. Y., Schnappinger D., Pethe K., Ehrt S. (2010). Gluconeogenic carbon flow of tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates is critical for Mycobacterium tuberculosis to establish and maintain infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 21, 9819–9824 10.1073/pnas.1000715107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer L., Bowling T., Perales J., Freeman J., Nguyen T., Bacchi C., et al. (2011). 2,4-Diaminopyrimidines as potent inhibitors of Trypanosoma brucei and identification of molecular targets by a chemical proteomics approach. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5:e956. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. (1983). Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 65, 55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto B. R. S., Zambuzzi-Carvalho P. F., Bailão A. M., Martins W. S., Soares C. M. A., Pereira M. (2014). Transcriptional profile of Paracoccidioides spp. in response to itraconazole. BMC Genomics 15:254. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira C. M. A., Silva M. R. R., Kato L., Silva C. C., Ferreira H. D., Souza L. K. H. (2004). Chemical composition and antifungal activity of the essential oil of Hyptis ovalifolia Benth. (Lamiaceae). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 5, 756–759. 10.1590/S0103-50532004000500023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira K. M., da Silva Neto B. R., Parente J. A., da Silva R. A., Quintino G. O., Voltan A. R., et al. (2013). Intermolecular interactions of the malate synthase of Paracoccidioides spp. BMC Microbiol. 13:107. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otzen C., Muller S., Jacobsen I. D., Brock M. (2013). Phylogenetic and phenotypic characterization of the 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase gene family from the opportunistic human pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 13, 553–564. 10.1111/1567-1364.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M., Song Z., Santos-Silva L. K., Richards M. H., Nguyen T. T., Liu J., et al. (2010). Cloning, mechanistic and functional analysis of a fungal sterol C24-methyltransferase implicated in brassicasterol biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1801, 1163–1174. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier Y., Antonenkov V. D., Glumoff T., Hiltunen J. K. (2006). Peroxisomal beta- oxidation-a metabolic pathway with multiple functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 1413–1426. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado M., Silva M. B., Laurenti R., Travassos L. R., Taborda C. P. (2009). Mortality due to systemic mycoses as a primary cause of death or in association with AIDS in Brazil: a review from 1996 to 2006. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 104, 513–521. 10.1590/S0074-02762009000300019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado R. S., Alves R. J., Oliveira C. M., Kato L., Silva R. A., Quintino G. O., et al. (2014). Inhibition of Paracoccidioides lutzii Pb01 isocitrate lyase by the natural compound argentilactone and its semi-synthetic derivatives. PLoS ONE 9:e94832. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo A., Jiménez B. (1980). Growth of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis yeast phase in a chemically defined culture medium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 12, 279–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittner G. M. G., Munoz J. E., Marques A., Nosanchuk J. D., Taborda C. P. (2012). Therapeutic DNA vaccine encoding peptide P10 against experimental paracoccidioidomycosis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6:e1519. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers P. D., Vermitsky J. P., Edlind T. D., Hilliard G. M. (2006). Proteomic analysis of experimentally induced azole resistance in Candida glabrata. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58, 434–438. 10.1093/jac/dkl221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J. C., Denny R., Dorschel C. A., Gorenstein M., Kass I. J., Li G. Z., et al. (2005). Quantitative proteomic analysis by accurate mass retention time pairs. Anal Chem. 77, 2187–2200. 10.1021/ac048455k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J. C., Gorenstein M. V., Li G. Z., Vissers J. P., Geromanos S. J. (2006). Absolute quantification of proteins by LC-MSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol. Cell Prot. 5, 144–156. 10.1074/mcp.M500230-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S. S., Tavares A. H., Passos-Silva D. G., Fachin A. L., Teixeira S. M., Soares C. M., et al. (2008). Transcriptional response of murine macrophages upon infection with opsonized Paracoccidioides brasiliensis yeast cells. Microbes Infect. 10, 12–20. 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N. P., McCoy M. T., Tice R. R., Schneider E. L. (1988). A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp. Cell. Res. 175, 184–191. 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober W. (2001). Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Appendix 3:Appendix 3B. 10.1002/0471142735.ima03bs21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares A. H., Silva S. S., Dantas A., Campos E. G., Andrade R. V., Maranhão A. Q., et al. (2007). Early transcriptional response of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis upon internalization by murine macrophages. Microbes Infect. 9, 583–590. 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira M. D. M., Theodoro R. C., Derengowski L. D. S., Nicola A. M., Bagagli E., Felipe M. S. (2013). Molecular and morphological data support the existence of a sexual cycle in species of the genus Paracoccidioides. Eukaryotic Cell. 12, 380–338. 10.1128/EC.05052-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice R. R., Agurell E., Anderson D., Burlinson B., Hartmann A., Kobayashi H., et al. (2000). Single cell gel/comet assay: guidelines for in vitro and in vivo genetic toxicology testing. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 35, 206–221. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(2000)35:33.0.CO;2-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travassos L. R., Taborda C. P., Colombo A. L. (2008). Treatment options for paracoccidioidomycosis and new strategies investigated. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 6, 251–262. 10.1586/14787210.6.2.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaíno J. A., Deutsch E. W., Wang R., Csordas A., Reisinger F., Ríos D., et al. (2014). ProteomeXchange provides globally co-ordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 223–226. 10.1038/nbt.2839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S. S., Parente A. F., Borges C. L., Parente J. A., Bailão A. M., de Almeida Soares C. M. (2012). Analysis of the secretomes of Paracoccidioides mycelia and yeast cells. PLoS ONE 7:e52470. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wang Y., Yan L., Liang R., Dai B., Tang R., et al. (2009). Proteomic analysis reveals a synergistic mechanism of fluconazole and berberine against fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans: endogenous ROS augmentation. J. Prot. Res. 8, 5296–5304. 10.1021/pr9005074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambuzzi-Carvalho P. F., Tomazett P. K., Santos S. C., Ferri P. H., Borges C. L., Martins W. S., et al. (2013). Transcriptional profile of Paracoccidioides induced by oenothein B, a potential antifungal agent from the Brazilian Cerrado plant Eugenia uniflora. BMC Microbiol. 13:227. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]