Abstract

Heat stress affects feed intake, milk production, and endocrine status in dairy cows. The temperature-humidity index (THI) is employed as an index to evaluate the degree of heat stress in dairy cows. However, it is difficult to ascertain whether THI is the most appropriate measurement of heat stress in dairy cows. This experiment was conducted to investigate the effects of heat stress on serum insulin, adipokines (leptin and adiponectin), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and heat shock signal molecules (heat shock transcription factor (HSF) and heat shock proteins (HSP)) in dairy cows and to research biomarkers to be used for better understanding the meaning of THI as a bioclimatic index. To achieve these objectives, two experiments were performed. The first experiment: eighteen lactating Holstein dairy cows were used. The treatments were: heat stress (HS, THI average=81.7, n=9) and cooling (CL, THI average=53.4, n=9). Samples of HS were obtained on August 16, 2013, and samples of CL were collected on April 7, 2014 in natural conditions. The second experiment: HS treatment cows (n=9) from the first experiment were fed for 8 weeks from August 16, 2013 to October 12, 2013. Samples for moderate heat stress, mild heat stress, and no heat stress were obtained, respectively, according to the physical alterations of the THI. Results showed that heat stress significantly increased the serum adiponectin, AMPK, HSF, HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90 (P<0.05). Adiponectin is strongly associated with AMPK. The increases of adiponectin and AMPK may be one of the mechanisms to maintain homeostasis in heat-stressed dairy cows. When heat stress treatment lasted 8 weeks, a higher expression of HSF and HSP70 was observed under moderate heat stress. Serum HSF and HSP70 are sensitive and accurate in heat stress and they could be potential indicators of animal response to heat stress. We recommend serum HSF and HSP70 as meaningful biomarkers to supplement the THI and evaluate moderate heat stress in dairy cows in the future.

Keywords: Heat stress, Dairy cows, Serum, Temperature-humidity index (THI), Biomarkers

1. Introduction

Despite advances in cooling systems and environmental management, heat stress continues to be a costly issue for the global animal agriculture industries (St-Pierre et al., 2003). Dairy cows are extremely sensitive to the hot environment (Bernabucci et al., 2014), and their alterations in the endocrine status (such as insulin) under heat stress have already been reported (Rhoads et al., 2009; O'Brien et al., 2010). In fact, heat stress does not only decrease milk yield by 35%–40% (West, 2003), but also leads to health problems and metabolic disorders (Wheelock et al., 2010; Bernabucci et al., 2014). Two adipokines secreted by adipose: leptin and adiponectin, are metabolically relevant in coordinating energy homeostasis (Ailhaud, 2006). However, little data is available on the interactions between heat stress and adipokines. To our knowledge, the effects of heat stress on leptin and adiponectin in dairy cows have not yet to be clearly elucidated. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) functions as a “fuel gauge” to monitor cellular energy status (Hardie et al., 2003). A variety of stresses are known to activate AMPK in mammals (Frederich et al., 2009). However, the relationship between heat stress and serum AMPK activity of dairy cows is still unclear.

Berman (2005) indicated that effective environmental temperature above 35 °C activated a heat stress response in dairy cows. Heat stress response includes activation of the heat shock transcription factor (HSF) and increased expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs) (Collier et al., 2008). Intriguing work demonstrates that extracellular HSP70 concentrations also increase during heat stress (Kavanagh et al., 2011; Gaughan et al., 2013). Therefore, we need to further investigate serum HSF and HSPs. HSF, a transcription factor family, has been demonstrated to be an important first responder during heat stress (Trinklein et al., 2004; Page et al., 2006). HSPs are considered as potential indicators of animal adaptation to harsh environmental stress and correlated with resistance to stress (Feder and Hofmann, 1999). There is little information reported that shows serum HSF and HSPs can be biomarkers during heat stress. Traditionally, the temperature-humidity index (THI) is employed as the index to evaluate the degree of heat stress in dairy cows (Bernabucci et al., 2014). The advantage of THI is that it is easy to use in practice, but THI is only a rough estimation of heat stress and not a direct reaction of animal metabolism. The radical physiological changes of heat-stressed dairy cows are intricate and multifactorial. Is THI the best indicator of heat stress in dairy cows? Further research is warranted to validate these potential predictive biomarkers to supplement the THI.

Therefore, the objective of this present study is to investigate the effects of heat stress on serum insulin, leptin, adiponectin, AMPK, HSF, HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90 in dairy cows and find out whether serum HSF and HSPs can be biomarkers to supplement the THI.

2. Materials and methods

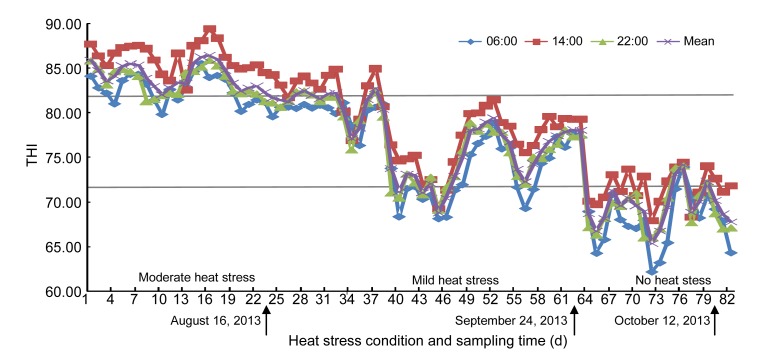

All animals involved in this study were cared for according to the principles of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee. The experiments were conducted at the Bright Dairy & Food Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). To achieve the objectives, two experiments were carried out. The first experiment: eighteen lactating Holstein dairy cows were used ((2.2±1.1) parities and (162±18) d in milk (DIM)). The treatments were: heat stress (HS, THI average=81.7, n=9) on August 16, 2013 and cooling (CL, THI average=53.4, n=9) on April 7, 2014 in natural conditions. Parities and DIM were similar between the treatments ((2.1±1.1) parities and (161±23) DIM for HS and (2.3±0.9) parities and (162±7) DIM for CL). Cows suffered HS and CL more than three weeks before sampling, respectively. The THI was calculated using the following equation: THI=[0.8×ambient temperature (°C)]+[(% relative humidity/100)×(ambient temperature−14.4)]+46.4 (Buffington et al., 1981). It was recorded at 06:00, 14:00, and 22:00 and in this experiment the THI presented a daily THI average. The second experiment: HS treatment cows (n=9) from first experiment were continuously fed for 8 weeks in natural conditions from August 16, 2013 to October 12, 2013. Serum samples were collected on August 16, 2013, September 24, 2013, and October 12, 2013. Their THI averages were 81.7, 78.0, and 68.9, respectively. According to the thresholds described by Armstrong (1994), they belonged to moderate, mild, and no heat stress in turn (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

THI pattern at 06:00, 14:00, 22:00 and mean during the different heat stress condition experimental periods

We collected serum samples at August 16, 2013, September 24, 2013, and October 12, 2013. The THI averages were 81.7, 78.0, and 68.9, respectively. Thresholds for moderate heat stress, mild heat stress, and no heat stress are from Armstrong (1994)

The basal diet (as total mixed ration (TMR)) was formulated to meet the nutrient requirements of energy, protein, minerals, and vitamins according to the Feeding Standards of Dairy Cattle in China (MOA, 2004). Diets were the same as our previous study (Cheng et al., 2014). Dry matter (DM) basis contained 16.7% corn silage, 8.7% Chinese wild rye, 14% alfalfa hay, 23% corn, 9.4% barley, 7.4% soybean meal, 3.4% cottonseed meal, 3.7% dry distillers grains, 3.4% rapeseed meal, 8.3% cottonseed, 0.54% dicalcium phosphate, 0.49% salt, 0.64% sodium bicarbonate, and 0.33% vitamin-mineral premix. The TMR contained 16.9% crude protein (CP), 39.1% neutral detergent fiber (NDF), 22.5% acid detergent fiber (ADF), 1.07% calcium, and 0.48% phosphorus with net energy of lactation (NEL) of 6.99 MJ/kg of DM. All dairy cows were fed TMR ad libitum and milked three times daily (at 06:00, 14:00, and 22:00). The daily milk yield and dry matter intake (DMI) were measured individually. Meanwhile, body temperature indices (rectal temperatures and respiration rates) were obtained three times daily (at 06:00, 14:00, and 22:00). Rectal temperatures were measured using a glass mercury thermometer and respiration rates were determined by counting the number of flank movements for 1 min.

Cows were serum sampled via the coccygeal vein puncture before morning feeding. Serum samples were obtained by centrifugation (3 000g for 10 min at 4 °C) and stored at −80 °C until analyzed. Serum samples were analyzed for insulin, leptin, adiponectin, AMPK, HSF, HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90 using commercially available enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay (ELISA) kits specific for bovine (Shanghai Enzyme-linked Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China).

Data for milk yield, DMI, rectal temperatures, respirations rates, and repeated-measures data (insulin, leptin, adiponectin, AMPK, HSF, HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90) were analyzed using the GLM procedure of SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The statistical model was as follows: Yij=μ+Ti+eij, where Yij is the dependent variable, μ is the overall mean, Ti is the treatment effect, and eij is the error term. Data were presented as least square means. Standard errors of the mean (SEM) are reported. Significance was declared at P<0.05.

3. Results and discussion

As expected, the rectal temperatures and respiration rates were markedly increased (P<0.05) in HS dairy cows (Table 1). Heat stress decreased DMI (P<0.05) and cows exposed to HS produced less milk compared with CL cows (P<0.05; Table 1). When evaluating the HS cows from the first experiment which lasted 8 weeks, the results showed that moderate heat stress dairy cows had higher rectal temperatures and respiration rates than mild heat stress and no heat stress (Table 2). Interestingly, rectal temperatures did not differ between mild heat stress and no heat stress at 06:00, 14:00, and 22:00. Meanwhile, no significant differences were observed on production variables (DMI and milk yield) between mild heat stress and no heat stress. Respiration rates were more sensitive at 06:00 and 14:00 to separate mild heat stress and no heat stress. The differences among moderate heat stress, mild heat stress, and no heat stress in dairy cows need to be further researched. In this sense, it is important to research other biomarkers to better understand the meaning of THI as a bioclimatic index.

Table 1.

Effects of heat stress and cooling treatments on body temperature variables and production variables in dairy cows

| Treatment (n=9) | Rectal temperature (°C) |

Respiration rate (breath/min) |

DMI (kg/d) | Milk yield (kg/d) | ||||

| 6:00 | 14:00 | 22:00 | 6:00 | 14:00 | 22:00 | |||

| HS | 39.01 | 39.31 | 39.17 | 68.58 | 85.00 | 67.25 | 17.89 | 26.11 |

| CL | 38.29 | 38.32 | 38.51 | 36.67 | 40.25 | 36.17 | 24.45 | 37.44 |

| SEM | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 3.79 | 4.99 | 3.64 | 0.26 | 0.93 |

| P-value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

HS: heat stress; CL: cooling; SEM: standard error of the mean. Heat stress and cooling treatments occurred in natural condition. All dairy cows were individually fed TMR ad libitum three times daily. Heat stress, THI average=81.7 and cooling, THI average=53.4

Table 2.

Effects of different heat stress period change on body temperature variables and production variables in dairy cows

| HS treatment (n=9) | Rectal temperature (°C) |

Respiration rate (breath/min) |

DMI (kg/d) | Milk yield (kg/d) | ||||

| 6:00 | 14:00 | 22:00 | 6:00 | 14:00 | 22:00 | |||

| Moderate | 39.01a | 39.31a | 39.17a | 68.58a | 85.00a | 67.25a | 17.89a | 26.11a |

| Mild | 38.54b | 38.70b | 38.54b | 46.75b | 52.75b | 52.70b | 19.48b | 30.68b |

| No | 38.55b | 38.69b | 38.60b | 37.12c | 43.58c | 46.08b | 20.02b | 33.28b |

| SEM | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 2.67 | 3.34 | 2.13 | 0.26 | 0.85 |

| P-value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

HS: heat stress; SEM: standard error of the mean. HS treatment from first experiment lasted 8 weeks to investigate the changes under moderate heat stress, mild heat stress, and no heat stress. The THI averages were 81.7, 78.0, and 68.9, respectively. Each of different heat stress period occurred in natural condition. All dairy cows were individually fed TMR ad libitum three times daily. Within columns, means with different letter superscripts (a–c) are significantly different (P<0.05)

Above all, we investigated the effects of heat stress on serum insulin, adipokines (leptin and adiponectin), AMPK, and heat shock signal molecules (HSF and HSPs) in dairy cows. No significant differences were observed in serum concentrations of insulin between HS and CL (P>0.05; Table 3). Li et al. (2006) and Rhoads et al. (2013) pointed out that proper insulin action is necessary to effectively mount a response to heat stress and minimize heat-induced damage. It is generally known that heat stress stimulates the concentrations of insulin (O'Brien et al., 2010; Wheelock et al., 2010). However, others insist that in heat-stressed dairy cows there is a reduction in feed intake, which prolongs the period of negative energy balance and this may lead to decreased serum concentrations of insulin (Rensis and Scaramuzzi, 2003; Marai et al., 2007). In our experiment, heat stress led to a significant reduction of DMI (P<0.05; Table 1). As we know, insulin is closely related to feed intake. So if we put the insulin data on a DMI basis (HS: insulin 0.51 ng/ml, DMI 17.89 kg/d vs. CL: insulin 0.57 ng/ml, DMI 24.45 kg/d), obviously heat stress stimulated the concentrations of insulin in the same DMI conditions.

Table 3.

Serum concentrations of insulin, leptin, adiponectin, AMPK, HSF, and HSPs between heat stress and cooling treatments in dairy cows

| Treatment (n=9) | Insulin (ng/ml) | Leptin (ng/ml) | Adiponectin (μg/ml) | AMPK (U/L) | HSF (ng/ml) | HSP27 (ng/L) | HSP70 (ng/ml) | HSP90 (ng/ml) |

| HS | 0.51 | 1.28 | 17.49 | 29.05 | 20.46 | 208.13 | 25.99 | 28.40 |

| CL | 0.57 | 1.08 | 11.29 | 19.57 | 12.52 | 132.82 | 13.61 | 25.98 |

| SEM | 0.02 | 0.07 | 1.22 | 2.02 | 1.71 | 14.49 | 2.47 | 0.55 |

| P-value | 0.11 | 0.17 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.011 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.018 |

HS: heat stress; CL: cooling; SEM: standard error of the mean. Heat stress and cooling treatments occurred in natural condition. All dairy cows were individually fed TMR ad libitum three times daily. Heat stress, THI average=81.7 and cooling, THI average=53.4

There was no significant differences in serum concentrations of leptin between HS and CL in Table 3 (P>0.05). Heat stress up-regulates leptin expression and secretion in mice and 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Bernabucci et al., 2009; Morera et al., 2012). Very little work has been done to evaluate changes and the biological role of leptin in heat-stressed dairy cows. We assumed that the amount of leptin changed in heat-stressed dairy cows. In fact, results suggested that heat stress may not directly affect the expression and secretion of leptin in dairy cows. If we put the leptin data on a DMI basis (HS: leptin 1.28 ng/ml, DMI 17.89 kg/d vs. CL: leptin 1.08 ng/ml, DMI 24.45 kg/d), heat stress increased the concentrations of leptin in the same DMI conditions.

Heat stress increased the serum concentrations of adiponectin in Table 3 (P<0.05). The up-regulation of adiponectin observed in this study agrees with previous findings in mice and 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Bernabucci et al., 2009; Morera et al., 2012), confirming a role of heat stress in modulating adiponectin expression. Park et al. (2005) pointed out that heat stress induced an increase in the fluidity of membrane lipids, may cause signal transduction that would induce the cellular heat shock response to increase the HSP expression, which could directly stimulate adiponectin expression. The up-regulation of adiponectin may be what is responsible to better resist the damaging effects of heat stress. We suggested that an increase of adiponectin might be one of the mechanisms involved in acclimation to heat stress as the feedback in dairy cows. The precise role of adiponectin in heat-stressed dairy cows warrants further investigation. The different responses between adiponectin and leptin to heat stress in the present study supports the notion that two adipokines may independently regulate biological functions in dairy cows.

The result showed that heat stress activated serum AMPK in Table 3 (P<0.05). Although the mechanism for AMPK release into serum remains ill-defined, determining serum AMPK may help in diagnosing metabolic diseases (Malvoisin et al., 2009). AMPK is involved in many types of stress response. The first treatments shown to activate AMPK were pathologic stresses such as heat stress (Corton et al., 1994). Heat stress has been shown to affect AMPK activity in the rock crab, AMPK activity increased by up to 9.1-fold from 18 to 30 °C (Frederich et al., 2009). Liu and Brooks (2012) found that 1 h mild heat stress in C2C12 myotubes up-regulated AMPK activity. Yamauchi et al. (2002) demonstrated that adiponectin activates AMPK in C2C12 myocytes, skeletal muscle, and liver; meanwhile, the activation of AMPK is necessary for the adiponectin-induced stimulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) phosphorylation, fatty-acid oxidation, glucose uptake, and lactate production in muscle cells. Adiponectin is strongly associated with AMPK. In this sense, the increase of adiponectin activated AMPK during heat stress, dairy cows may enhance adiponectin and AMPK to cope with their adaptation to heat stress.

As expected, serum HSF, HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90 levels increased significantly during heat stress (P<0.05; Table 3). Transcriptionally active HSF increases the expression of HSPs that promote the refolding of misfolded proteins (Li et al., 2011). Overexpression of HSPs protects against hyperthermia during heat stress (Lee et al., 2006). The rise in the concentration of HSF and HSPs could serve as a rapid protective mechanism against heat stress to maintain the homeostasis. Whether serum HSF and HSPs can be biomarkers during heat stress has not yet been reported.

THI is employed as an index, which is a single value combining effects of air temperature and humidity, and to evaluate the degree of heat stress in dairy cows (Bernabucci et al., 2014). THI has been used for more than four decades to assess heat stress in dairy cows. However, the THI does not include management factors (the effect of shade) or animal factors (genotype differences) (Gaughan et al., 2008). It is only a rough estimation of heat stress, not a direct reaction of animal metabolism. Bohmanova et al. (2007) demonstrated the THI differs in its ability to detect heat stress in the semiarid climate of Arizona and the humid climate of Georgia. Conceptually, it is difficult to ascertain whether the THI is the most appropriate measurement of heat stress in dairy cows (Dikmen and Hansen, 2009). We hypothesized that serum signal molecules during heat shock response can be biomarkers to identify heat stress in dairy cows.

HS significantly resulted in more HSF, HSP27, HSP70, and HSP90 (Table 3). However, when evaluating HS from the first experiment which lasted 8 weeks, the results showed no significant differences in HSP27 and HSP90 among moderate heat stress, mild heat stress, and no heat stress. Compared with mild heat stress and no heat stress dairy cows, moderate heat stress dairy cows had a higher expression of HSF and HSP70 (P<0.05; Table 4).

Table 4.

Serum concentrations of HSF and HSPs among moderate heat stress, mild heat stress, and no heat stress in dairy cows

| HS treatment (n=9) | HSF (ng/ml) | HSP27 (ng/L) | HSP70 (ng/ml) | HSP90 (ng/ml) |

| Moderate | 20.46a | 208.13 | 25.99a | 28.40 |

| Mild | 13.86b | 169.80 | 16.57b | 27.94 |

| No | 13.75b | 172.11 | 16.78b | 27.53 |

| SEM | 1.21 | 8.86 | 1.60 | 0.51 |

| P-value | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.012 | 0.80 |

HS: heat stress; SEM: standard error of the mean. HS treatment from the first experiment lasted 8 weeks to investigate the changes under moderate heat stress, mild heat stress, and no heat stress. The THI averages were 81.7, 78.0, and 68.9, respectively. Each of different heat stress period occurred in natural condition. All dairy cows were individually fed TMR ad libitum three times daily. Within columns, means with different letter superscripts (a and b) are different (P<0.05)

Serum HSF and HSP70 were more sensitive and accurate in heat stress. A transcription factor family known as the HSF has been implicated as an important first responder during heat stress (Trinklein et al., 2004; Page et al., 2006). Among all the HSPs, HSP70 is the most inducible protein after thermal stress (Tanaka et al., 1988), the most abundant and temperature sensitive (Beckham et al., 2004). Their expression acts as potential indicators of animal adaptation to harsh environmental stress (Hansen, 2004). Wang et al. (2003) suggested HSP70 expression kinetics at different temperatures may be an important cause of the “second window of protection.” The HSP70 helped in conferring the thermo-adaptability and high level of heat resistance (Patir and Upadhyay, 2010). Gaughan et al. (2013) suggested that the blood concentration of HSP70 is a reliable indicator of heat stress. We supposed that serum HSF and HSP70 might be biomarkers to identify heat stress. We can monitor serum HSF and HSP70 changes to alert heat stress in dairy cows in the near future.

4. Conclusions

To summarize, we speculate on the proposed heat stress model for endocrine and metabolic responses in dairy cows. Heat stress may not directly affect the secretion of insulin and leptin. However, if we put the data on a DMI basis, heat stress increased the concentrations of insulin and leptin under the same DMI conditions. During heat stress, the increase of adiponectin activated AMPK and dairy cows may enhance adiponectin and AMPK to cope with their adaptation to heat stress. Moreover, heat shock response activates HSF and increases the expression of HSPs to protect against hyperthermia. The main effects of these acclimatory responses are to coordinate metabolism to maintain homeostasis in heat stress. Additionally, serum HSF and HSP70 are sensitive and accurate in heat stress and they could be potential indicators of animal responses to heat stress. With the progress of technology, the determination of HSP and HSF in serum will be valuable. We recommend serum HSF and HSP70 as meaningful biomarkers and monitor their changes to alert heat stress in dairy cows in the future.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Peng-peng WANG (Institute of Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for her suggestions about the text revisions.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Basic Research Program (973) of China (No. 2011CB100805), the Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System of China (No. nycytx-04-01), and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (No. ASTIP-IAS12), China

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Li MIN, Jian-bo CHENG, Bao-lu SHI, Hong-jian YANG, Nan ZHENG, and Jia-qi WANG declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

References

- 1.Ailhaud G. Adipose tissue as a secretory organ: from adipogenesis to the metabolic syndrome. C R Biol. 2006;329(8):570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong D. Heat stress interaction with shade and cooling. J Dairy Sci. 1994;77(7):2044–2050. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(94)77149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckham JT, Mackanos MA, Crooke C, et al. Assessment of cellular response to thermal laser injury through bioluminescence imaging of heat shock protein 70. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;79(1):76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2004.tb09860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman A. Estimates of heat stress relief needs for Holstein dairy cows. J Anim Sci. 2005;83(6):1377–1384. doi: 10.2527/2005.8361377x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernabucci U, Basiricò L, Morera P, et al. Heat shock modulates adipokines expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2009;42(2):139–147. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernabucci U, Biffani S, Buggiotti L, et al. The effects of heat stress in italian Holstein dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97(1):471–486. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-6611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohmanova J, Misztal I, Cole JB. Temperature-humidity indices as indicators of milk production losses due to heat stress. J Dairy Sci. 2007;90(4):1947–1956. doi: 10.3168/jds.2006-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buffington D, Collazo-Arocho A, Canton G, et al. Black globe-humidity index (BGHI) as comfort equation for dairy cows. Trans ASAE. 1981;24(3):0711–0714. doi: 10.13031/2013.34325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng JB, Bu DP, Wang JQ, et al. Effects of rumen-protected γ-aminobutyric acid on performance and nutrient digestibility in heat-stressed dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97(9):5599–5607. doi: 10.3168/jds.2013-6797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collier R, Collier J, Rhoads R, et al. Invited review: genes involved in the bovine heat stress response. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91(2):445–454. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corton JM, Gillespie JG, Hardie DG. Role of the AMP-activated protein kinase in the cellular stress response. Curr Biol. 1994;4(4):315–324. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dikmen S, Hansen PJ. Is the temperature-humidity index the best indicator of heat stress in lactating dairy cows in a subtropical environment? J Dairy Sci. 2009;92(1):109–116. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feder ME, Hofmann GE. Heat-shock proteins, molecular chaperones, and the stress response: evolutionary and ecological physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61(1):243–282. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frederich M, O'Rourke MR, Furey NB, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in the rock crab, Cancer irroratus: an early indicator of temperature stress. J Exp Biol. 2009;212(Pt 5):722–730. doi: 10.1242/jeb.021998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaughan J, Bonner S, Loxton I, et al. Effects of chronic heat stress on plasma concentration of secreted heat shock protein 70 in growing feedlot cattle. J Anim Sci. 2013;91(1):120–129. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaughan JB, Mader TL, Holt SM, et al. A new heat load index for feedlot cattle. J Anim Sci. 2008;86(1):226–234. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen P. Physiological and cellular adaptations of zebu cattle to thermal stress. Anim Reprod Sci. 2004;82-83:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardie DG, Scott JW, Pan DA, et al. Management of cellular energy by the AMP-activated protein kinase system. FEBS Lett. 2003;546(1):113–120. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00560-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kavanagh K, Flynn DM, Jenkins KA, et al. Restoring HSP70 deficiencies improves glucose tolerance in diabetic monkeys. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300(5):E894–E901. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00699.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee WC, Wen HC, Chang CP, et al. Heat shock protein 72 overexpression protects against hyperthermia, circulatory shock, and cerebral ischemia during heatstroke. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(6):2073–2082. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01433.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li G, Ali IS, Currie RW. Insulin induces myocardial protection and Hsp70 localization to plasma membranes in rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(4):H1709–H1721. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00201.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li QL, Ju ZH, Huang JM, et al. Two novel SNPs in HSF1 gene are associated with thermal tolerance traits in Chinese Holstein cattle. DNA Cell Biol. 2011;30(4):247–254. doi: 10.1089/dna.2010.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu CT, Brooks GA. Mild heat stress induces mitochondrial biogenesis in C2C12 myotubes. J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(3):354–361. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00989.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malvoisin E, Livrozet JM, El Hajji-Ridah I, et al. Detection of AMP-activated protein kinase in human sera by immuno-isoelectric focusing. J Immunol Methods. 2009;351(1-2):24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MOA (Ministry of Agriculture of China) Feeding Standard of Dairy Cattle, NY/T 34-2004. Beijing, China: MOA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marai I, El-Darawany A, Fadiel A, et al. Physiological traits as affected by heat stress in sheep—a review. Small Ruminant Res. 2007;71(1-3):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2006.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morera P, Basirico L, Hosoda K, et al. Chronic heat stress up-regulates leptin and adiponectin secretion and expression and improves leptin, adiponectin and insulin sensitivity in mice. J Mol Endocrinol. 2012;48(2):129–138. doi: 10.1530/JME-11-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'brien M, Rhoads R, Sanders S, et al. Metabolic adaptations to heat stress in growing cattle. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2010;38(2):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Page TJ, Sikder D, Yang L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of human HSF1 signaling reveals a transcriptional program linked to cellular adaptation and survival. Mol Biosyst. 2006;2(12):627–639. doi: 10.1039/b606129j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park H, Han S, Oh S, et al. Cellular responses to mild heat stress. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(1):10–23. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patir H, Upadhyay R. Purification, characterization and expression kinetics of heat shock protein 70 from Bubalus bubalis . Res Vet Sci. 2010;88(2):258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rensis FD, Scaramuzzi RJ. Heat stress and seasonal effects on reproduction in the dairy cow—a review. Theriogenology. 2003;60(6):1139–1151. doi: 10.1016/S0093-691X(03)00126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhoads M, Rhoads R, Vanbaale M, et al. Effects of heat stress and plane of nutrition on lactating Holstein cows: I. production, metabolism, and aspects of circulating somatotropin. J Dairy Sci. 2009;92(5):1986–1997. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhoads RP, Baumgard LH, Suagee JK, et al. Nutritional interventions to alleviate the negative consequences of heat stress. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(3):267–276. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.St-Pierre N, Cobanov B, Schnitkey G. Economic losses from heat stress by us livestock industries. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86:E52–E77. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)74040-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka K, Jay G, Isselbacher KJ. Expression of heat-shock and glucose-regulated genes: differential effects of glucose starvation and hypertonicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;950(2):138–146. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trinklein ND, Murray JI, Hartman SJ, et al. The role of heat shock transcription factor 1 in the genome-wide regulation of the mammalian heat shock response. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(3):1254–1261. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang S, Diller KR, Aggarwal SJ. Kinetics study of endogenous heat shock protein 70 expression. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125(6):794–797. doi: 10.1115/1.1632522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.West J. Effects of heat-stress on production in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci. 2003;86(6):2131–2144. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73803-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wheelock JB, Rhoads RP, Vanbaale MJ, et al. Effects of heat stress on energetic metabolism in lactating Holstein cows. J Dairy Sci. 2010;93(2):644–655. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, et al. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med. 2002;8(11):1288–1295. doi: 10.1038/nm788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]