Abstract

Background

After the implementation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs), the marked shift in Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pnc) serotype distribution led to a modification in pneumococcal antibiotic susceptibility. In 2011, the pattern of antibiotic prescription in France for acute otitis media in infants was greatly modified, with decreased use of third-generation cephalosporins and amoxicillin–clavulanate replaced by amoxicillin alone. To assess antibiotic strategies, here we measured the antibiotic susceptibility of Pnc and Haemophilus influenzae (Hi) isolated from nasopharyngeal flora in infants with acute otitis media in the 13-valent PCV (PCV13) era in France.

Methods

From November 2006 to June 2013, 77 pediatricians obtained nasopharyngeal swabs from infants (6 to 24 months old) with acute otitis media. The swabs were sent for analysis to the national reference centre for pneumococci in France. Demographics, medical history, and physical examination findings were recorded.

Results

We examined data for 7200 children, 3498 in the pre-PCV13 period (2006–2009) and 3702 in the post-PCV13 period (2010–2013). The Pnc carriage rate decreased from 57.9 % to 54.2 % between the 2 periods, and the proportion of pneumococcal strains with reduced susceptibility to penicillin or resistant to penicillin decreased from 47.1 % to 39 % (P < 0.0001). The Hi carriage rate increased from 48.2 % to 52.4 %, with the proportion of ß-lactamase–producing strains decreasing from 17.1 % to 11.9 % and the proportion of ß-lactamase–nonproducing, ampicillin-resistant strains remaining stable, from 7.7 % to 8.2 %. We did not identify any risk factor associated with carriage of ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains (such as daycare center attendance, otitis-prone condition or recent antibiotic use).

Conclusion

In France, the nasopharyngeal carriage rate of reduced-susceptibility pneumococcal strains and ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains decreased in children with acute otitis media after 2010, the year the PCV13 was introduced. Accordingly, amoxicillin as the first-line drug for acute otitis media requiring antibiotics remains a valid choice.

Keywords: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Conjugate vaccine, PCV, Otitis media, Antibiotic, Guideline, Blnar, Betalactamase, Haemophilus influenzae

Background

Acute otitis media (AOM) is the most frequent bacterial infection in childhood and one of the major indications for antibiotics in many countries [1]. Streptococcus pneumoniae (Pnc) and Haemophilus influenzae (Hi) are the leading bacterial species implicated in AOM, followed by Moraxella catarrhalis (Mc) and, to a lesser extent, group A β-hemolytic streptococci [2]. For AOM, Pnc and Hi are the main targets of antibiotics prescription [3, 4]. Detection of bacterial species in the middle ear fluid (MEF) by culture is the “gold standard” for etiologic diagnosis of AOM [5].

Few medical centers in Europe or the United States continue to routinely perform tympanocentesis [6, 7]. The decrease in centers performing tympanocentesis probably reflects no new antibiotics introduced for AOM [5]. Tympanocentesis or myringotomy (both considered painful) are performed mainly for special circumstances: antibiotics non-response, recurrent cases and chronic OM. Therefore, the profile of antibiotics resistance among otopathogens isolated from MEF could be biased and we have no current MEF microbiology data on which to base treatment decisions for the most frequent situations: first-line AOM seen by pediatricians or general practitioners. Because the microbiology of AOM is linked to nasopharyngeal (NP) flora, many studies have assessed the possibility of using NP culture, a painless procedure, to predict the bacterial etiology of AOM [5, 8]. These studies have shown that if Pnc or Hi is not found in the nasopharynx, the isolates will not likely be found in the MEF in case of AOM. However, because the causative bacteria of AOM are often isolated from NP cultures in addition to other organisms, the positive predictive value of this type of sample for the causative agent is poor [9].

For these reasons, NP culture has not been considered a useful predictor of AOM etiology in clinical practice. However, if NP cultures are not useful for treatment for specific patients with AOM, they may be useful on a population basis for formulating recommendations in one country or in different regions [5].

In France, 7 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) was introduced for high risk children < 2 years old in 2002, then for all children < 2 years old in 2006. PCV7 coverage reached 86 % in 2008. In June 2010, the French authorities recommended routine vaccination with PCV13 of infants at 2, 4 and 12 months old to replace PCV7. During a one-year transition period, switching from PCV7 to PCV13 was recommended at any point in the schedule to complete the immunization series. The PCV vaccination coverage for children younger than 2 years after changing from PCV7 to PCV13 is greater than 92 % [10].

Since the implementation of PCV7 and PCV13, two major and related changes have occurred: the Pnc serotype distribution has shifted, which has led to a modification in pneumococcal antibiotic susceptibility. The changes in antibiotic susceptibility could also result from other factors such as variations in antibiotic consumption (volume and type of compound used) or rate of children cared for outside the home [3, 4, 11]

Since 2000, to follow the changes induced by PCV implementation, our research group has analyzed several hundred NP samples from children with AOM all over France each year [12]. The data obtained during the first years of the study have served as the basis for the guidelines published in 2011 for France [3, 13], which recommended amoxicillin, 80–90 mg/kg/d in 2 or 3 daily intakes, as first-line therapy for AOM in young children. Indeed, the guidelines stated that amoxicillin was the most active agent for pneumococci with decreased susceptibility to penicillin and was active for more than 85 % of nontypable Hi according to microbiologic data at the time [3]. Since 2011, 2 major changes have occurred: the implementation of 13-valent PCV (PCV13) and the shift in antibiotic prescription for AOM, with decreased use of third-generation cephalosporins and amoxicillin–clavulanate replaced by amoxicillin [14, 15].

A rapid change in resistance of Pnc and Hi to the commonly used antimicrobials prompts a reevaluation of the treatment strategies [8]. To assess this question, we measured NP carriage and antibiotic susceptibility of these 2 otopathogens in young children with AOM in the PCV13 era in France.

Methods

From November 2006 to June 2013, 77 French pediatricians throughout France took part in a cross-sectional study. An NP swab was obtained from children aged 6 to 24 months with a diagnosis of purulent AOM [16]. We excluded children who had received antibiotics within 7 days before enrolment, had a severe underlying health disorder, or had been included in the study during the previous 12 months. Demographic data, medical history and physical findings were recorded. To monitor the impact of the introduction of PCV13 on this ecological niche, 2 periods were defined: pre-PCV13 (2006–2009) and post-PCV13 (2010–2013).

The study was approved by the Saint Germain en Laye Ethics Committee (CPP île de France XI, 20 rue Armagis, 78105 Saint Germain en Laye Cedex, France), and written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians.

Microbiology investigations

NP specimens were obtained with use of cotton-tipped wire swabs. The swabs were inserted into the anterior nares, gently rubbed on the NP wall and immediately placed in transport medium (Copan Venturi Transystem, Brescia, Italy). The samples were transferred within 48 h to Robert Debré Hospital and to the national reference center for pneumococci in France.

Pnc culture, identification, serotyping and antibiotic susceptibility testing were performed as previously described [17]. Susceptibility of Pnc isolates to penicillin G and erythromycin was determined from minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) by the agar-dilution method. Isolates were classified as penicillin-susceptible (MIC ≤ 0.06 μg/ml), penicillin–non-susceptible (MIC ≥ 0.12 μg/ml), penicillin–intermediate-resistant (MIC 0.12–2.0 μg/ml), or penicillin-resistant (MIC > 2 μg/ml) according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/).

Isolates of Hi were identified by colony morphology assay and conventional methods of determination. Hi isolates underwent capsular serotyping by the slide agglutination method with specific antisera (Phadebact; Boule Diagnostics, Huddinge, Sweden). The production of ß-lactamase was assessed by a chromogenic cephalosporin test (Nitrocefin; Cefinase; Biomerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). H. influenzae strains were further classified as ampicillin susceptible (MIC ≤ 1 mg/L), or resistant (MIC > 1 mg/L). ß-lactamase negative ampicillin resistance (BLNAR) was determined according to the CLSI break points [18]. If the 2 μg ampicillin diffusion test (Becton Dickinson) gave a zone of inhibition <20 mm and if the cefalotin disk diffusion test gave a zone of inhibition <17 mm, strains were considered BLNAR [19].

Statistical analysis

Data were double-entered by using 4D software 6.4 and analyzed by using Stata SE 13.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) for univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression (odds ratios [ORs] and 95 % confidence intervals [95 % CI]). Chi-square test was used to compare NP carriage of pneumococci and Hi before and after PCV13 implementation. Factors related to NP carriage were identified on univariate analysis (p < 0.20, chi-square test). Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the main factors associated with carriage of Pnc, Pnc strains with reduced susceptibility to penicillin (RSP), Hi carriage, and ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains. For these models, factors had to be determined by the physician during the visits. When different factors were highly correlated, such as recent antibiotic use, history of AOM and otitis-prone children, we retained the most relevant factor. The following variables were included in multivariate logistic regression models: daycare attendance, siblings, recent antibiotic treatment (within 3 months before enrolment), otalgia + fever ≥38.5 °C, conjunctivitis, and bilateral AOM. All models were adjusted for age. Age was dichotomized as <1 and ≥ 1 year. The cut-off of 1 year was chosen because the vaccination schedules differ before and after this age (reflecting the immunity maturation); in many studies, the NP carriage is higher after 1 year; and in one of our studies, young age (<1 year) predicted penicillin non-susceptible pneumococci carriage [20].

Results

During the 7 years, we assessed samples for 7200 patients (3498 in the pre-PCV13 period and 3702 in the post-PCV13 period). Table 1 shows demographic characteristics and NP carriage of the children enrolled. Median age was 13 months (Q1–Q3 9–17 months) and more than 99 % were PCV-vaccinated, including 3399 (47.2 %) with PCV13. Among the children, 44.8 % attended a daycare center and 45.1 % had received antibiotics within 3 months before inclusion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children with acute otitis media before/after 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine implementation in France

| Child characteristics | Before PCV13 | After PCV13 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3,498 (%) | n = 3,702 (%) | ||

| Male sex | 1,848 (52.8) | 1,982 (53.5) | 0.5 |

| Age (months), mean ± SD | 13.5 ± 5.0 | 13.7 ± 5.0 | 0.05 |

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 12.7 (9.4-17.2) | 13.0 (9.5-17.5) | |

| Type of care | <0.0001 | ||

| Daycare center | 1437 (41.1) | 1784 (48.2) | |

| Childminder | 1099 (31.4) | 1148 (31.0) | |

| Home | 959 (27.4) | 770 (20.8) | |

| Antibiotics 3 months before enrolment | 1652 (47.3) | 1591 (43.0) | <0.0001 |

| Only 1 antibiotic | 1035 (62.7) | 1051 (66.1) | 0.04 |

| At least 2 antibiotics | 617 (37.4) | 539 (33.9) | |

| Cephalosporin | 809 (49.1) | 393 (24.8) | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 670 (40.7) | 561 (35.4) | <0.0001 |

| Amoxicillin | 116 (7.0) | 598 (37.7) | |

| Others antibiotic | 52 (3.2) | 34 (2.1) | |

| Last antibiotic in | |||

| the previous month | 607 (36.7) | 601 (37.8) | |

| 1 to 2 months | 681 (41.2) | 666 (41.9) | 0.50 |

| 2 to 3 months | 364 (22.0) | 324 (20.4) | |

| Sibling | 1975 (56.5) | 2071 (55.9) | 0.65 |

| Conjunctivitis | 886 (25.3) | 1062 (28.7) | 0.001 |

| Otalgia | 2595 (74.3) | 2686 (72.6) | 0.1 |

| Fever (≥38.5 °C) | 2061 (59.4) | 2052 (55.9) | 0.003 |

| Otalgia + fever ≥38.5 °C | 1564 (44.7) | 1543 (41.7) | 0.009 |

| Bilaterala | 492/900 (54.7) | 1858 (50.2) | 0.02 |

| History of AOMb | 1005/1793 (56.1) | 2047 (55.3) | 0.6 |

| Otitis-prone childrenb | 349/1793 (19.5) | 651 (17.6) | 0.09 |

| Pnc carriage | 2026 (57.9) | 2007 (54.2) | 0.002 |

| Hi carriage | 1686 (48.2) | 1938 (52.4) | <0.0001 |

adata not available in 2006/2008, bdata not available in 2006/2007

AOM: Acute Otitis Media; PCV13: 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; Q1-Q3, quartiles 1 to 3; Pnc: pneumococcus; Hi: H. influenzae

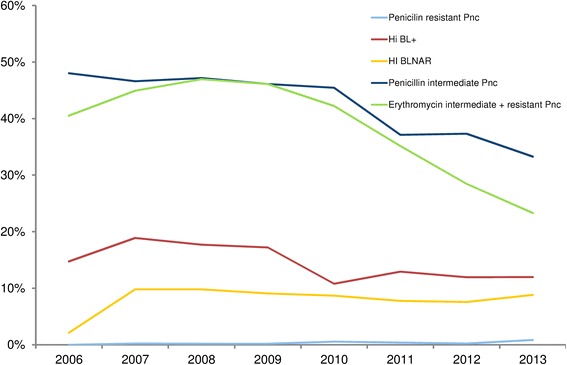

The Pnc carriage rate decreased from 57.9 % to 54.2 % between the pre- and post-PCV13 period, and the proportion of Pnc strains with reduced susceptibility to penicillin or resistant to penicillin decreased from 47.1 % to 39 % (P < 0.0001) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). In the pre-PCV13 period, pneumococcal penicillin–non-susceptible strains were represented by serotypes 19A, 15A, 35B and 19 F. Among the Pnc carriers, between the two periods, the proportion of PCV7 serotype and 6 additional PCV13 serotypes decreased from 9.5 % to 3.2 % (P < 0.001) and from 32.0 % to 11.1 % (P < 0.001), respectively. Serotype 19A, the most frequently serotype identified during the whole study, decreased from 22.6 % to 8.4 % between the 2 periods. By contrast, non-PCV13 serotypes increased from 58.5 % to 85.7 % (P < 0.001). The most frequently carried non-PCV13 serotypes in post PCV13 period were serotype 15B/C (12.2 %), 15A (9.3 %), 11A (9.1 %), 35B (7.5 %), 23A (5.9 %), and 6C (5.0 %), 33 other serotypes accounted for 34.9 %. In this period, pneumococcal penicillin–non-susceptible strains were predominantly represented by serotypes 11A, 15A, 15B/C, 19A and 35B. Non-typeable Pnc remained stable (2.1 % to 1.8 %) between the 2 periods.

Table 2.

Nasopharyngeal carriage and resistance of Pnc and Hi in children with AOM before/after PCV13 implementation

| Carriage | Before PCV13 | After PCV13 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3,498 (%) | n = 3,702 (%) | ||

| Pnc | 2026 (57.9) | 2007 (54.2) | |

| Penicillin susceptible | 1069 (52.9) | 1223 (61.0) | <0.001 |

| Penicillin intermediate-resistant | 950 (47.0) | 772 (38.5) | |

| Penicillin resistant | 3 (0.1) | 10 (0.5) | |

| Erythromycin susceptible | 1119 (55.3) | 1351 (67.4) | <0.001 |

| Erythromycin intermediate | 109 (5.4) | 42 (2.1) | |

| Erythromycin resistant | 794 (39.3) | 613 (30.6) | |

| PCV7 vaccine types | 193(9.5) | 64 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Additional PCV13 vaccine types | 648 (32.0) | 223 (11.1) | |

| Non-vaccine types | 1185 (58.5) | 1720 (85.7) | |

| Hi | 1686 (48.2) | 1938 (52.4) | |

| ß-lactamase–producing strains | 289 (17.1) | 230 (11.9) | <0.001 |

| BLNAR+ | 130 (7.7) | 159 (8.2) | 0.74 |

| ß-lactamase + BLNAR- | 264 (15.7) | 209 (10.8) | |

| ß-lactamase + BLNAR+ | 25 (1.4) | 21 (1.1) | |

| ß-lactamase- BLNAR+ | 105 (6.2) | 138 (7.1) | |

| ß-lactamase- BLNAR- | 1292 (76.6) | 1570 (81.0) | |

| No carriage | 693 (19.8) | 773 (20.9) | |

| Hi or Pnc carriage | 1898 (54.3) | 1913 (51.7) | 0.09 |

| Hi and Pnc carriage | 907 (25.9) | 1016 (27.4) |

Pnc: pneumococcus; Hi: H. influenzae; BLNAR: ß-lactamase–nonproducing ampicillin-resistant

Fig. 1.

Antibiotic resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae isolated from nasopharyngeal flora in 7200 infants with acute otitis media between 2006 and 2013. Pnc: pneumococcus; Hi: H. influenzae; BL+: ß-lactamase–producing strains; BLNAR: ß-lactamase–nonproducing ampicillin-resistant strains

The Hi carriage rate increased from 48.2 % to 52.4 % between the pre- and post-PCV13 period. During the whole study, 18/3624 (0.5 %) Hi isolates were serotype b. The proportion of ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains decreased from 17.1 % (n = 289) to 11.9 % (n = 230) and that of ß-lactamase–nonproducing, ampicillin-resistant (BLNAR) strains remained stable, < 10 %, with 7.7 % and 8.2 % in the pre- and post-PCV13 periods (Table 2).

On multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3), the main factors associated with RSP-Pnc carriage were daycare center attendance (adjusted OR [aOR] = 1.55, 95 % CI [1.36;1.77]), age < 1 year old (aOR = 1.19, 95 % CI [1.04;1.35]), and antibiotic use within 3 months (aOR = 1.78, 95 % CI [1.56;2.03]. In contrast, decreased RSP-Pnc carriage was associated with presence of siblings and post-PCV13 period (aOR = 0.75, 95 % CI [0.65;0.85]) and (aOR = 0.71, 95 % CI [0.62;0.81]). Factors associated with Hi carriage were conjunctivitis (aOR = 4.10, 95 % CI [3.54;4.76]), bilateral AOM (aOR = 1.33, 95 % CI [1.17;1.51]), daycare center attendance (aOR = 1.93, 95 % CI [1.70;2.19]), age < 1 year old (aOR = 1.49, 95 % CI [1.31;1.69]), presence of siblings aOR = 1.82, 95 % CI [1.60;2.07]), and post-PCV13 period (aOR = 1.23, 95 % CI [1.05;1.44]). Post-PCV13 period was the only factor retained in the ß-lactamase–producing Hi carriage model and was associated with decreased carriage (aOR = 0.65, 95 % CI [0.54;0.79]).

Table 3.

Risk factors of nasopharyngeal carriage of Pnc, strains with reduced susceptibility to penicillin (RSP) Pnc, Hi and ß-lactamase + Hi strains by univariate and multivariate analysis

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | P value | aOR | 95 % CI | P value | |

| Carriage of Pnc* | ||||||

| Otalgia + fever ≥38.5 °C | 1.39 | 1.26;1.53 | <10−4 | 1.29 | 1.17;1.42 | <10−4 |

| Daycare centre | 1.33 | 1.21;1.46 | <10−4 | 1.61 | 1.46;1.78 | <10−4 |

| Siblings | 1.32 | 1.20;1.45 | <10−4 | 1.45 | 1.31;1.60 | <10−4 |

| Age <1 year | 1.03 | 0.94 ;1.14 | 0.48 | 1.04 | 0.95 ;1.15 | 0.39 |

| Recent use of cephalosporin | 0.98 | 0.86;1.11 | 0.74 | |||

| Bilateral AOMa | 0.94 | 0.84;1.06 | 0.33 | |||

| Otitis-prone childrenb | 0.91 | 0.79;1.04 | 0.16 | |||

| Periods (post-PCV13) | 0.86 | 0.78;0.94 | 0.002 | 0.84 | 0.77 ;0.93 | 0.01 |

| History of AOMb | 0.86 | 0.77;0.96 | 0.005 | |||

| Hi carriage | 0.79 | 0.72 ;0.86 | <10−4 | |||

| Recent use of antibiotics | 0.78 | 0.71 ;0.86 | <10−4 | 0.73 | 0.66 ;0.81 | <10−4 |

| Conjunctivitis | 0.47 | 0.42;0.52 | <10−4 | 0.47 | 0.42;0.52 | <10−4 |

| Carriage of RSP Pnc** | ||||||

| Recent use of antibiotics | 1.88 | 1.66 ;2.14 | <10−4 | 1.78 | 1.56 ;2.03 | <10−4 |

| Day care centre | 1.68 | 1.48;1.91 | <10−4 | 1.55 | 1.36 ;1.77 | <10−4 |

| Recent use of cephalosporin | 1.63 | 1.38;1.92 | <10−4 | |||

| Otitis-prone childrenb | 1.60 | 1.33;1.93 | <10−4 | |||

| History of AOMb | 1.58 | 1.36;1.83 | <10−4 | |||

| Bilateral AOMa | 1.15 | 0.98;1.35 | 0.08 | |||

| Age <1 year | 1.08 | 0.96 ;1.23 | 0.21 | 1.19 | 1.04 ;1.35 | 0.009 |

| Conjunctivitis | 1.08 | 0.93;1.26 | 0.33 | |||

| Hi carriage | 0.95 | 0.84 ;1.08 | 0.46 | |||

| Otalgia + fever ≥38.5 °C | 0.93 | 0.82;1.06 | 0.27 | |||

| Periods (post-PCV13) | 0.72 | 0.63 ;0.81 | <10−4 | 0.71 | 0.62 ;0.81 | <10−4 |

| Siblings | 0.70 | 0.62 ;0.80 | <10−4 | 0.75 | 0.65 ;0.85 | <10−4 |

| Carriage of Hi*** | ||||||

| Conjunctivitis | 4.22 | 3.76 ;4.74 | <10−4 | 4.10 | 3.54 ;4.76 | <10−4 |

| Daycare centre | 1.74 | 1.58 ;1.91 | <10−4 | 1.93 | 1.70;2.19 | <10−4 |

| History of AOMb | 1.65 | 1.48 ;1.83 | <10−4 | |||

| Otitis-prone childrenb | 1.54 | 1.34 ;1.77 | <10−4 | |||

| Siblings | 1.49 | 1.36 ;1.64 | <10−4 | 1.82 | 1.60;2.07 | <10−4 |

| Bilateral AOMa | 1.47 | 1.31 ;1.65 | <10−4 | 1.33 | 1.17 ;1.51 | <10−4 |

| Recent use of antibiotics | 1.42 | 1.29;1.56 | <10−4 | 1.28 | 1.12;1.45 | <10−4 |

| Age <1 year | 1.37 | 1.25 ;1.50 | <10−4 | 1.49 | 1.31;1.69 | <10−4 |

| Recent use of cephalosporin | 1.19 | 1.05 ;1.35 | 0.005 | |||

| Periods (post-PCV13) | 1.18 | 1.08;1.29 | <10−3 | 1.23 | 1.05;1.44 | 0.01 |

| Otalgia + fever ≥38.5 °C | 0.84 | 0.76;0.92 | <10−3 | |||

| Pnc carriage | 0.79 | 0.72 ;0.86 | <10−4 | |||

| Carriage of ß-lactamase producing Hi**** | ||||||

| Otitis-prone childrenb | 1.27 | 0.99 ;1.64 | 0.06 | |||

| Recent use of cephalosporin | 1.21 | 0.96 ;1.53 | 0.11 | |||

| History of AOMb | 1.18 | 0.94;1.48 | 0.16 | |||

| Recent use of antibiotics | 1.17 | 0.97 ;1.40 | 0.11 | |||

| Age <1 year | 1.16 | 0.96;1.40 | 0.12 | 0.86 | 0.72;1.04 | 0.13 |

| Conjunctivitis | 1.10 | 0.91 ;1.33 | 0.32 | |||

| Bilateral AOMa | 0.96 | 0.76 ;1.23 | 0.76 | |||

| Otalgia + fever ≥38.5 °C | 0.94 | 0.78;1.14 | 0.52 | |||

| Siblings | 0.91 | 0.75 ;1.10 | 0.33 | |||

| Daycare centre | 0.90 | 0.75;1.08 | 0.27 | |||

| Pnc carriage | 0.89 | 0.74 ;1.08 | 0.24 | |||

| Periods (post-PCV13) | 0.65 | 0.54 ;0.78 | <10−4 | 0.65 | 0.54 ;0.79 | <10−4 |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; 95 % CI, 95 % confidence interval; Pnc: pneumococcus; Hi: H. influenzae; AOM: Acute otitis medi; a adata not available in 2006/2008, bdata not available in 2006/2007

*univariate and multivariate analysis of overall population (n = 7,200), with 4,033 Pnc carriers; **univariate and multivariate analysis of Pnc carriers (n = 4,033), with 1,735 RSP Pnc carriers; ***univariate and multivariate analysis of overall population (n = 7,200), with 3,624 Hi carriers; ****univariate analysis of Hi carriers (n = 3,624), with 519 ß-lactamase+

Discussion

The levels of resistance to antibiotic for S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae are the cornerstones of the rationale for antimicrobial recommendations for AOM [5, 8]. In 2011, guidelines in France designated amoxicillin as the first-line drug for AOM requiring antibiotics, with amoxicillin-clavulanate and cefpodoxime proxetil limited to rare and specific situations [3]. These guidelines were based on a decreased proportion of ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains in France [13]. Complying with these 2011 recommendations, in 2012, the most frequently (66 %) prescribed antibiotic for AOM in France was amoxicillin, as was recently shown [14, 15]. Conversely, prescriptions of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as amoxicillin-clavulanate and cefpodoxime proxetil sharply decreased [14, 15].

Since 2011 (Fig. 1), the NP carriage of RSP-Pnc decreased 18 % in the post-PCV13 period. Moreover, this reduction was associated with a decrease (−20 %) in the carriage of ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains. Accordingly, amoxicillin as the first-line drug for AOM requiring antibiotics remains an adapted recommendation in France. In addition, we did not identify any risk factor associated with carriage of ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains (such as daycare center attendance, otitis-prone condition or recent antibiotic use). Taking into account the low proportion of ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains and the lack of risk factors associated with their carriage, the prescription of amoxicillin-clavulanate as the first-line drug for AOM in this situation seems to have no benefit or justification.

The decrease in antibiotic resistance to S. pneumoniae was expected [21]. As in other studies, the reduction is linked to the 66 % decrease in the 6 additional PCV13 serotypes in our study [21, 22]. Despite a dramatically decrease of vaccine serotypes, 19A known in France to harbor a high proportion of RSP remained frequently isolated in post PCV13 period (8.4 %) [23]. Several non-vaccine serotypes such as 15B/C (12.2 %), 15A (9.3 %), 11A (9.1 %), 35B (7.5 %), 23A (5.9 %), and 6C (5.0 %) seem to emerge in the post PCV13 period.

In contrast, the decrease in ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains was not expected. Two explanations could be raised. The first is the reduced antibiotic use for children in France. Since 2001, following a national campaign promoting a judicious use of antibiotics in France, antibiotic use in children has been sharply reduced, particularly for children < 2 years [24]. Furthermore, PCV implementation may have led to an additional reduction in prescriptions [25]. The second hypothesis is more speculative: in our population, most Hi strains now produce biofilms [26], which allows for resistance to antibiotic treatments without another mechanism of resistance required [27, 28].

PCV13 impact in our population was expected since we have already showed the impact of PCV7 on carriage and antibiotic resistance [11]. We have previously showed in pre PCV13 period that Pnc carriage was less frequently associated with AOM treatment failure than Hi [29]. However, in this current study, we have not analyzed the evolution of risk of AOM antibiotic failure between pre and post PCV13 periods.

This situation of infection and antibiotic resistance is very dynamic and the few non-vaccine strains of S. pneumoniae, which are resistant to penicillin, may, similar to serotype 19A, become more prevalent. This possibility underscores the importance of the continuous availability of current data that reflects local and national microbiologic trends.

Conclusion

The NP carriage rate of RSP-Pnc strains and ß-lactamase–producing Hi strains has decreased in children with AOM in France since 2010, the year of PCV13 implementation in France. Accordingly, amoxicillin as the first-line drug for AOM requiring antibiotics remains a valid recommendation. However, the AOM microbiology is evolving and requires continuous monitoring and adjustments of policy for antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

We thank all pediatricians who participated in the study: C Abt-Nord, M-J Aim-Mille, D Allain, M Amzallag, I Aubier, P Bakhache, J Baron, B Baszanger, G Beley, M Benani, C Bensoussan-Ambacher, E Billard, L Billet, J-P Blanc, M-J Bodin, E Boez, B Bohe, J Bouglé, F Bouillot, J-L Cabos, P Camier, F Ceccato, D Clavel, C Claverie, R Cohen, L Coicadan, F Corrard, L Cret, B de Brito, F De Grenier, P Deberdt, I Defives, A Delatour, V Derkx, V Desvignes, M Dogneton, I Donikian-Pujol, M Dubosc, C Dumont, A Elbez, J Elbhar, N Elkhoury, C Ferte-Devin, J-M Fiorini, D Garel, J-L Gasnier, A Gasser, B Gaudin, N Gelbert-Baudino, C Georgeot, M Gerardin, M Giorno, R Gorge, J-L Guillon, J-F Hassan, A Hayat, P Huguet, M Hunin, A Kalindjian, K Kassmann, Z Klink, M Koskas, C Lastman-Lahmi, M-C Lemarchand, J-C Lévêque, J Levy, D Livon, N Maamri, M-O Mercier-Oger, C Messica, A-S Michot, J Miclot, P Migault, I Nave, M Navel, J-F Nicolas, A Pappo, J Peguet, C Perrin, C Petit, O Pinard, A Piollet, J-F Pujol, M-T Pujol, Y Regnard, M Robert, C Turberg-Romain, O Romain, M-C Rondeau, C Schlemmer, G Sivelle, D Somerville, N Temam-Basse, J-M Thiron, F Thollot, J Vaugeois, F Vie Le Sage, J-L Vuillemin, A Werner, R Wisnewsky, A Wollner, C Wollner, C Ythier.

We thank M Boucherat, M Fernandes, I Ramay, D Menguy, C Prieur, and Elsa Sobral for technical assistance.

Funding

Financial support was given by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals France.

The sponsor helped design the study but had no role in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Grants for ACTIV from Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi and GSK during the conduct of the study.

Dr François Angoulvant reports personal fees from Pfizer outside the submitted work.

Dr Robert Cohen reports personal fees from Pfizer, GSK, Sanofi and Novartis outside the submitted work.

Dr Emmanuelle Varon reports personal fees and non-financial support from Pfizer, personal fees from GSK, outside the submitted work.

Dr Corinne Levy reports personal fees from Pfizer and Novartis outside the submitted work.

Authors’ contributions

The followings authors contributed as follows: RC, SBE, SBO, EV, CL conceived and design the study. FA RC CD AE AW SBO EV performed the data acquisition. FA RC CD AE AW SBE SBO EV CL analyzed the study. FA RC CD AE AW SBE SBO EV CL contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

François Angoulvant, Email: francois.angoulvant@nck.aphp.fr.

Robert Cohen, Email: robert.cohen@wanadoo.fr.

Catherine Doit, Email: catherine.doit@rdb.aphp.fr.

Annie Elbez, Email: active@activ-france.fr.

Andreas Werner, Email: docteur.werner.pediatre@wanadoo.fr.

Stéphane Béchet, Email: stephane.bechet@activfrance.fr.

Stéphane Bonacorsi, Email: stephane.bonacorsi@rdb.aphp.fr.

Emmanuelle Varon, Email: emmanuelle.varon@egp.aphp.fr.

Corinne Levy, Email: corinne.levy@activ-france.fr.

References

- 1.Sabuncu E, David J, Bernede-Bauduin C, Pepin S, Leroy M, Boelle PY, et al. Significant reduction of antibiotic use in the community after a nationwide campaign in France, 2002–2007. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gehanno P, Panajotopoulos A, Barry B, Nguyen L, Levy D, Bingen E, et al. Microbiology of otitis media in the Paris, France, area from 1987 to 1997. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:570–3. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azria R, Barry B, Bingen E, Cavallo JD, Chidiac C, Francois M, et al. Antibiotic stewardship. Med Mal Infect. 2012;42:460–87. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2012.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, Ganiats TG, Hoberman A, Jackson MA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e964–99. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wald ER, DeMuri GP. Commentary: antibiotic recommendations for acute otitis media and acute bacterial sinusitis in 2013–the conundrum. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:641–3. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182868cc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Shimol S, Givon-Lavi N, Leibovitz E, Raiz S, Greenberg D, Dagan R. Near-Elimination of Otitis Media Caused by 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) Serotypes in Southern Israel Shortly After Sequential Introduction of 7-Valent/13-Valent PCV. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1724–32. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey JR, Kaur R, Friedel VC, Pichichero ME. Acute otitis media otopathogens during 2008–2010 in Rochester NY. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:805–9. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828d9acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vergison A. Microbiology of otitis media: a moving target. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 7):G5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Dongen TM, van der Heijden GJ, van Zon A, Bogaert D, Sanders EA, Schilder AG. Evaluation of concordance between the microorganisms detected in the nasopharynx and middle ear of children with otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:549–52. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318280ab45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy C, Varon E, Picard C, Béchet S, Martinot A, Bonacorsi S, et al. Trends of pneumococcal meningitis in children after introduction of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in France. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:1216–21. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen R, Bingen E, Levy C, Thollot F, Boucherat M, Derkx V, et al. Nasopharyngeal flora in children with acute otitis media before and after implementation of 7 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in France. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen R, Levy C, Bonnet E, Grondin S, Desvignes V, Lecuyer A, et al. Dynamic of pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage in children with acute otitis media following PCV7 introduction in France. Vaccine. 2010;28:6114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy C, Thollot F, Corrard F, Lecuyer A, Martin P. Boucherat M et al [Acute otitis media in ambulatory practice: epidemiological and clinical characteristics after 7 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) implementation] Arch Pediatr. 2011;18:712–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angoulvant F, Pereira M, Perreaux F, Soussan V, Pham LL, Trieu TV, et al. Impact of unlabeled French antibiotic guidelines on antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory tract infections in 7 Pediatric Emergency Departments, 2009–2012. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:330–3. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy C, Pereira M, Guedj R, Abt-Nord C, Gelbert NB, Cohen R, et al. Impact of 2011 French guidelines on antibiotic prescription for acute otitis media in infants. Med Mal Infect. 2014;44:102–6. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paradise JL. On classifying otitis media as suppurative or nonsuppurative, with a suggested clinical schema. J Pediatr. 1987;111:948–51. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen R, Levy C, de La Rocque F, Gelbert N, Wollner A, Fritzell B, et al. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and of reduction of antibiotic use on nasopharyngeal carriage of nonsusceptible pneumococci in children with acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:1001–7. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000243163.85163.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wayne P. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 18th informational supplement: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008.

- 19.Norskov-Lauritsen N, Ridderberg W, Erikstrup LT, Fuursted K. Evaluation of disk diffusion methods to detect low-level beta-lactamase-negative ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae. APMIS. 2011;119:385–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen R, Levy C, Bonnet E, Thollot F, Boucherat M, Fritzell B, et al. Risk factors for serotype 19A carriage after introduction of 7-valent pneumococcal vaccination. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dagan R, Leibovitz E, Greenberg D, Bakaletz L, Givon-Lavi N. Mixed pneumococcal-nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae otitis media is a distinct clinical entity with unique epidemiologic characteristics and pneumococcal serotype distribution. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1152–60. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin JM, Hoberman A, Paradise JL, Barbadora KA, Shaikh N, Bhatnagar S, et al. Emergence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serogroups 15 and 35 in nasopharyngeal cultures from young children with acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:e286–90. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen R, Levy C, Bingen E, Koskas M, Nave I, Varon E. Impact of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage in children with acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:297–301. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318247ef84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dommergues MA, Hentgen V. Decreased paediatric antibiotic consumption in France between 2000 and 2010. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:495–501. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.669840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmu AA, Jokinen J, Nieminen H, Rinta-Kokko H, Ruokokoski E, Puumalainen T, et al. Effect of pneumococcal Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV10) on outpatient antimicrobial purchases: a double-blind, cluster randomised phase 3–4 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:205–12. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizrahi A, Cohen R, Varon E, Bonacorsi S, Bechet S, Poyart C, et al. Non typable-Haemophilus influenzae biofilm formation and acute otitis media. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:400. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–22. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swords WE. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae biofilms: role in chronic airway infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:97. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caeymaex L, Varon E, Levy C, Béchet S, Derkx V, Desvignes V, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of acute otitis media in children carrying streptococcus pneumoniae or haemophilus influenzae in their nasopharynx as a single otopathogen after introduction of the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:533–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]