Abstract

Covered stents have rarely been used in neuroendovascular procedures. We report the case of a 74-year-old woman with a complex iatrogenic vascular injury from attempted insertion of a hemodialysis catheter: concurrent brachiocephalic artery pseudoaneurysm and common carotid artery to internal jugular vein fistula. Both lesions were excluded successfully by using two balloon-expandable covered stents with a satisfactory short-term clinical and angiographic outcome.

Keywords: Fistula, Intervention, Trauma, Stent

Background

Inadvertent complications of jugular vein catheterization for temporary hemodialysis are not uncommon; however, common carotid artery (CCA) to internal jugular vein (IJV) fistula (CJF) and brachiocephalic pseudoaneurysm have been rarely reported.1–3 Traditionally, management of such vascular complications consists of open surgery, which is subject to technical difficulty and a high morbidity rate.4 5 Endovascular techniques using covered stent grafts may provide a technically simple, safe, and durable solution to supra-aortic vascular injuries.5–7

We describe our experience with two covered stent grafts for treatment of a patient with concurrent brachiocephalic pseudoaneurysm and CJF caused by iatrogenic injuries from insertion of a hemodialysis catheter.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old woman with a past medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease, left cardiac failure (NYHA stage II–III), arterial hypertension, and chronic renal failure with renal transplant failure was admitted to a peripheral hospital. There, the attempt to introduce a single-lumen Demers catheter (Bionic, Medizintechnik GmbH, Friedrichsdorf, Germany) into the right IJV for hemodialysis access was unsuccessful and a hematoma developed in the right cervical area. Thereafter, the patient complained of dysphagia and hoarseness and noticed a thrill over her right clavicular area, which was audible on auscultation of the right carotid artery during the following days. The neurologic examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

A CT scan revealed a hematoma in the right lower neck and mediastinum along with mediastinal emphysema. CT angiography (CTA) performed 19 days later demonstrated a large pseudoaneurysm of the brachiocephalic artery (figure 1A) along with a CJF from the proximal right CCA to IJV (figure 2A). The patient was subsequently transferred to our neurovascular center and discussed at the interdisciplinary neurovascular board. It was decided to treat the pseudoaneurysm first due to a suspected higher risk of rupture.

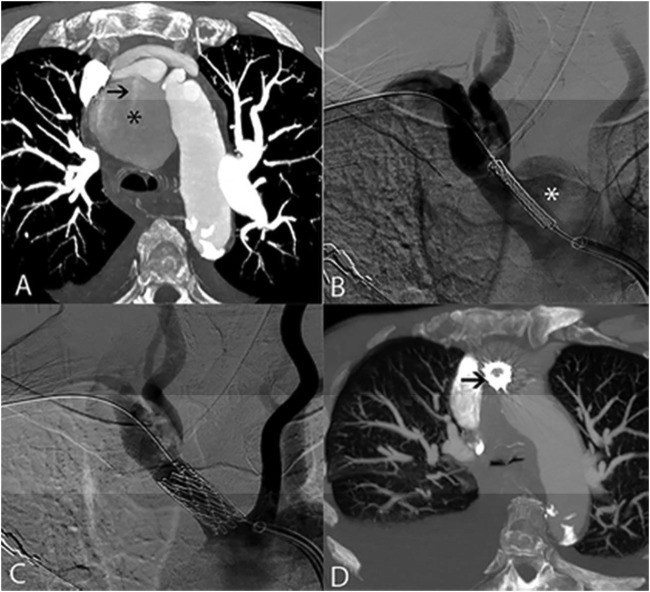

Figure 1.

Brachiocephalic artery pseudoaneurysm (asterisk) is demonstrated on CT angiography (CTA) (A) and digital subtraction angiography (B) images, the latter also showing the unexpanded covered stent in place prior to its deployment. Contrast jet into the aneurysmal sac is evident on CTA (arrow in A). After expansion of the covered stent in the brachiocephalic artery, the aneurysm shows no residual filling (C). Follow-up CTA after 3 months shows no residual pseudoaneurysm (D); a patent covered stent is found inside the brachiocephalic artery (arrow in D).

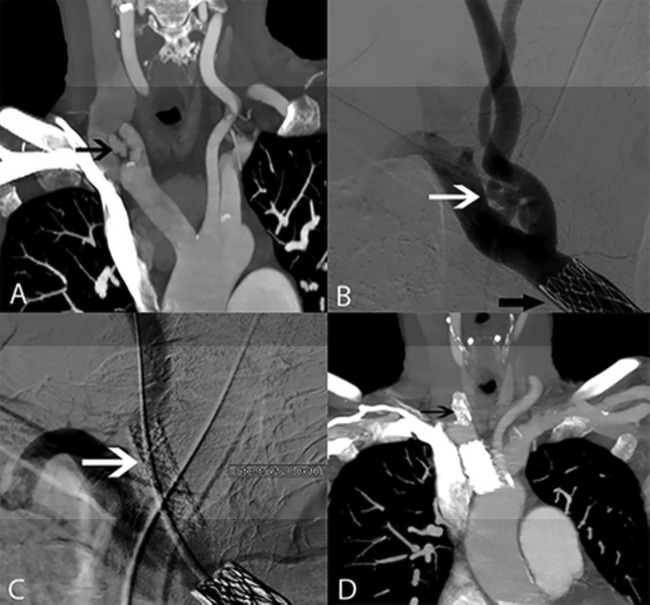

Figure 2.

(A) CT angiography (CTA) shows early contrast filling of the internal jugular vein (IJV) related to the fistula from the proximal common carotid artery (CCA) to the IJV (black arrow). (B) Digital subtraction angiography shows the fistula (white arrow) with faint IJV filling as well as the previously placed stent in the brachiocephalic artery (black arrow). A V12 covered stent (white and black arrows in C and D, respectively) is placed in the proximal CCA just from its origin to exclude the fistula (C) with disappearance of early IJV filling. On control CTA after 3 months (D), there is no evidence of residual fistula filling.

Treatment

Both procedures were done under general anesthesia. Before each procedure the patient was loaded with aspirin and clopidogrel, with functional tests showing adequate inhibition of platelets. After femoral artery puncture and insertion of a 9 F sheath, angiography confirmed the presence of both the pseudoaneurysm and CJF. The right subclavian artery was then catheterized and a 12 F long sheath was advanced over an exchange wire to the origin of the brachiocephalic artery. A balloon-expandable covered stent graft (Covered Cheatham Platinum (CPP), NuMED, New York, USA) of 14 mm diameter×34 mm length, which was hand-crimped on a 40 mm long balloon (Balloon in Balloon (BIB), NuMED), was deployed in the brachiocephalic artery (diameter 16 mm proximal and 12 mm distal to the pseudoaneurysm on CTA) to cover the pseudoaneurysm (figure 1B). Final angiography demonstrated complete exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm (figure 1C).

The thrill subsided immediately but the murmur reappeared on auscultation of the carotid artery 17 days after the procedure. Subsequent ultrasound revealed an increased flow of arteriovenous shunt at the right IJV, which directly prompted the second procedure to exclude the CJF. Via right femoral artery access, the brachiocephalic artery was catheterized and a 9 F (60 cm) sheath was exchanged and advanced to the stented brachiocephalic artery. A second balloon-expandable covered stent (Advanta V12 8.0/38 mm, Atrium Medical, Hudson, New Hampshire, USA) was then placed into the proximal right CCA to exclude the CJF (figure 2B). Control angiography revealed no evidence of residual arteriovenous fistula, while the right CCA remained patent (figure 2C).

Outcome and follow-up

The immediate post-interventional course was uneventful except for pneumonia which was successfully treated with oral ciprofloxacin. After an intraprocedural bolus (5000 IU), intravenous heparin was maintained for 24 h (target partial thromboplastin time 30–40 s) and the patient was discharged on dual antiplatelet medication with aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) for 3 months to be continued with aspirin for 12 months. The patient’s dysphagia resolved immediately while her hoarseness improved gradually. She remained neurologically asymptomatic. Three months later a control CTA demonstrated complete occlusion of both lesions along with patency of the stent grafts (figures 1D and 2D).

The patient had several comorbidities including chronic renal failure with ongoing hemodialysis, so further annual follow-up imaging is arranged to be done by non-invasive vascular ultrasound.

Discussion

Complex iatrogenic injury of the extracranial supra-aortic vessels is rare. Since the patient had several comorbidities and was not suitable for open surgical repair, we decided to perform endovascular treatment. Stent-assisted coiling was not regarded as a good choice since both lesions were rather large with a high risk of early recanalization. We used balloon-expandable stent grafts for exclusion of both lesions. These stent grafts provide two major advantages: first, exact positioning is possible without major foreshortening or stent migration during deployment, which was critical in this case at the origin of the CCA from the brachiocephalic artery; second, adjustment of the graft to the vessel caliber is possible by overdilating the graft and thus precluding any endoleak.

The indications for covered stent grafts in neurointerventional procedures are controversial and their application in such procedures has not been approved by the FDA.6 A review of case reports treated for traumatic extracranial internal carotid artery (ICA) pseudoaneurysms showed safety and short-term efficacy of covered stents.7 Agid et al8 reported the successful use of a self-expanding covered stent (VIABAHN, GORE) in a case of iatrogenic CCA puncture. A few case reports have described the feasibility of covered stents for excluding iatrogenic CJF following failed IJV catheterizations.1 9 Ahmed et al10 reported successful insertion of a balloon-expandable covered stent (Advanta V12) in a patient with an iatrogenic brachiocephalic artery pseudoaneurysm caused by biopsy at mediastinoscopy. Likewise, Axisa et al11 used a balloon-expandable covered stent (customized polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft on Palmaz stent) for exclusion of a traumatic brachiocephalic pseudoaneurysm without evidence of recurrent aneurysm or in-stent stenosis at 18 months follow-up. In a patient with traumatic distal brachiocephalic artery transection and pseudoaneurysm, Huang et al used two self-expanding overlapping stent grafts (10×50 mm and 12×10 mm Wallgraft endoprosthesis, Boston Scientific) to cover the distance from the CCA to the orifice of the brachiocephalic artery with no neurological complication and patent stent grafts at 1 year follow-up.12 De Troia et al13 used a covered stent (12×30 mm Wallgraft) to treat an innominate artery pseudoaneurysm following subclavian vein cannulation with a patent stent at 16 months follow-up.

Injury to the brachiocephalic artery carries a high morbidity and mortality risk due to a propensity for massive hemorrhage, associated traumatic injuries, and the risk of cerebral hypoperfusion and stroke. Open surgery of innominate artery injury represents a formidable challenge for experienced surgeons and is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates (5–43%), mainly due to its inaccessibility.5 10 Endovascular repair using covered stents has therefore been advocated as the treatment of choice in stable patients despite the limited number of reports. However, inadvertent overstenting of CCA origin should be avoided in more distal lesions.5 Likewise, surgical treatment of an arteriovenous fistula is difficult and requires closure of the fistula with arterial and venous reconstruction.

We observed no immediate technical or clinical complication and no in-stent stenosis or thrombosis at 3 months follow-up. An immediate complication rate of 9.1% is reported for covered stent procedures in the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries, with embolic stroke (1.2%) and dissection (1.8%) being the most worrisome.6 In two of four patients, McCready et al reported symptomatic cerebral thromboembolic events during covered stent deployment for exclusion of carotid artery pseudoaneurysm.14 In a patient with carotid blowout syndrome that was initially treated with Palmaz/PTFE covered stent, acute dissection of the CCA developed which was treated with two self-expanding Nitinol stents.15 Although the long-term safety and patency of covered stent grafts remains unknown, a total occlusion rate of 8.3% (9/109 patients, all asymptomatic) was reported for covered stents in the vertebral and carotid arteries whereas in-stent stenosis was found in another 4/109 patients.6 Layton et al used covered stent grafts (hand-crimped PTFE grafts) to treat two cases of extracranial ICA pseudoaneurysm and one case of recurrent intimal hyperplasia within an uncovered wall stent in the cervical ICA. During long-term follow-up they observed no intimal hyperplasia in the stent grafts, while high-grade stenosis developed in one case within a portion of a previously placed wall stent not covered by the stent graft.16

Learning points.

Endovascular treatment of complex iatrogenic injuries of the large supra-aortic arteries including brachiocephalic pseudo-aneurysm and CJF is safe and effective.

Despite restrictions, we advocate using balloon-expandable covered stents for treatment of life-threatening vascular injuries.

The ease of technical application and low rate of complications favor this treatment option, although its long-term durability and safety remain unknown.

Footnotes

Contributors: SK: planning the report, gathering data and information, writing the manuscript. JG: planning the procedure, advising, gathering information, revision. SE: planning and conducting the procedure, advising, revision. HU: supervision and management, conducting the procedure, revision and final approval. SM: conducting the procedure, planning the report, preparing figures, revising the manuscript and final approval.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Wadhwa R, Toms J, Nanda A et al. Angioplasty and stenting of a jugular-carotid fistula resulting from the inadvertent placement of a hemodialysis catheter: case report and review of literature. Semin Dial 2012;25:460–3. 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.01005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel HV, Sainaresh VV, Jain SH et al. Carotid-jugular arteriovenous fistula: a case report of an iatrogenic complication following internal jugular vein catheterization for hemodialysis access. Hemodial Int 2011;15:404–6. 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2011.00556.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrocheilou G, Kokkinis C, Stathopoulou S et al. Iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm of the brachiocephalic artery: a rare complication of Hickman line insertion. Int Urol Nephrol 2008;40:1107–10. 10.1007/s11255-008-9439-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahcebasi S, Kocyigit I, Akyol L et al. Carotid-jugular arteriovenous fistula and cerebrovascular infarct: a case report of an iatrogenic complication following internal jugular vein catheterization. Hemodial Int 2011;15:284–7. 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.du Toit DF, Odendaal W, Lambrechts A et al. Surgical and endovascular management of penetrating innominate artery injuries. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;36:56–62. 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alaraj A, Wallace A, Amin-Hanjani S et al. Endovascular implantation of covered stents in the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries: case series and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int 2011;2:67 10.4103/2152-7806.81725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maras D, Lioupis C, Magoufis G et al. Covered stent-graft treatment of traumatic internal carotid artery pseudoaneurysms: a review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2006;29:958–68. 10.1007/s00270-005-0367-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agid R, Simons M, Casaubon LK et al. Salvage of the carotid artery with covered stent after perforation with dialysis sheath. A case report. Interv Neuroradiol 2012;18:386–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Quinones M, Bargallo X, Blasco J et al. Iatrogenic carotid-jugular arteriovenous fistula: color Doppler sonographic findings and treatment with covered stent. J Clin Ultrasound 2006;34:301–5. 10.1002/jcu.20222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed I, Katsanos K, Ahmad F et al. Endovascular treatment of a brachiocephalic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to biopsy at mediastinoscopy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2009;32:792–5. 10.1007/s00270-008-9450-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Axisa BM, Loftus IM, Fishwick G et al. Endovascular repair of an innominate artery false aneurysm following blunt trauma. J Endovasc Ther 2000;7:245–50. 10.1177/152660280000700313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang C-L, Kao H. Endovascular management of post-traumatic innominate artery transection with pseudo-aneurysm formation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2008;72:569–72. 10.1002/ccd.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Troia A, Tecchio T, Azzarone M et al. Endovascular treatment of an innominate artery iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm following subclavian vein catheterization. Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011;45:78–82. 10.1177/1538574410388308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCready RA, Divelbiss JL, Bryant MA et al. Endoluminal repair of carotid artery pseudoaneurysms: a word of caution. J Vasc Surg 2004;40:1020–3. 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoppe H, Barnwell SL, Nesbit GM et al. Stent-grafts in the treatment of emergent or urgent carotid artery disease: review of 25 cases. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;19:31–41. 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Layton KF, Kim YW, Hise JH. Use of covered stent grafts in the extracranial carotid artery: report of three patients with follow-up between 8 and 42 months. Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:1760–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]