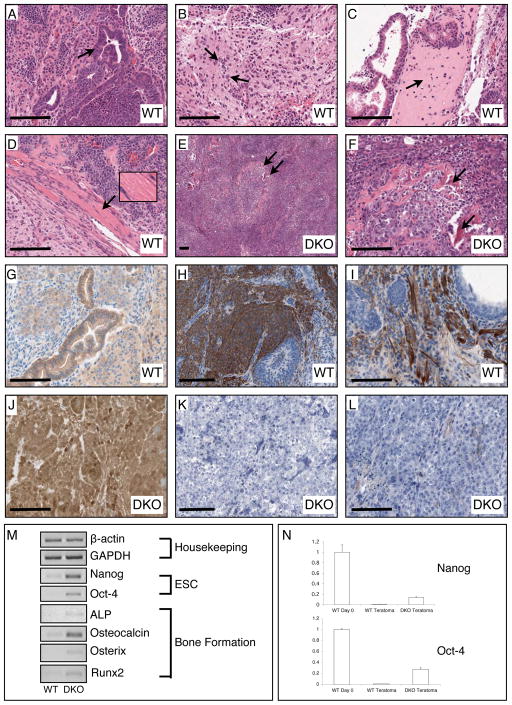

Figure 6.

Histological, immunohistochemical, and PCR examination of teratomas generated from WT (GSK-3α(flx/flx)) and DKO ES cells. (A) The WT teratomas possess numerous examples of glandular epithelial structures indicative of endoderm (arrow indicates gut-like pseudostratified epithelium). (B) WT tumours also had large regions of neuronal tissue indicating differentiation into ectoderm (arrows point to neuronal nuclei). (C) Differentiation of WT ESCs into mesoderm was confirmed by observation of bone (arrow points to region of woven bone) and (D) muscle (inset shows magnification of striated skeletal muscle). (E, F) DKO teratomas contain tightly packed cells in undifferentiated tissue reminiscent of a carcinoma with scattered spicules of bone (arrows). (G) Immunohistochemical staining for β-catenin revealed normal membranous staining in epithelial cells of WT teratomas. H, I) Staining for the neuronal progenitor marker Nestin and the astrocytic marker GFAP was clearly observed in WT teratomas. (J) DKO teratomas displayed very high levels of β-catenin immunoreactivity in all cells in membrane, cytosol and nuclear compartments. (K, L) There was no detectable staining for Nestin or GFAP in DKO teratoma tissue sections. (M) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analyses of WT vs. DKO gene expression. Bar = 100 μm.