Abstract

Early and aggressive treatment of circulatory failure is associated with increased survival, highlighting the need for monitoring methods capable of early detection. Vasoconstriction and decreased oxygenation of the splanchnic circulation are a sentinel response of the cardiovasculature during circulatory distress. Thus, we measured esophageal oxygenation as an index of decreased tissue oxygen delivery caused by three types of ischemic insult, occlusive decreases in mesenteric blood flow, and hemodynamic adaptations to systemic hypoxia and simulated hemorrhagic stress. Five anesthetized lambs were instrumented for monitoring of mean arterial pressure, mesenteric artery blood flow, central venous hemoglobin oxygen saturation, and esophageal and buccal microvascular hemoglobin oxygen saturation (StO2). The sensitivities of oximetry monitoring to detect cardiovascular insult were assessed by observing responses to graded occlusion of the descending aorta, systemic hypoxia due to decreased FIO2, and acute hemorrhage. Decreases in mesenteric artery flow during aortic occlusions were correlated with decreased esophageal StO2 (R2 = 0.41). During hypoxia, esophageal StO2 decreased significantly within 1 min of initiation, whereas buccal StO2 decreased within 3 min, and central venous saturation did not change significantly. All modes of oximetry monitoring and arterial blood pressure were correlated with mesenteric artery flow during acute hemorrhage. Esophageal StO2 demonstrated a greater decrease from baseline levels as well as a more rapid return to baseline levels during reinfusion of the withdrawn blood. These experiments suggest that monitoring esophageal StO2 may be useful in the detection of decreased mesenteric oxygen delivery as may occur in conditions associated with hypoperfusion or hypoxia.

Keywords: Splanchnic circulation, mesenteric artery, hypoxia, ischemia, hemorrhage

Introduction

Monitoring disturbances in tissue oxygen delivery can be useful in the care of critically ill patients experiencing circulatory complications such as cardiac failure and hypovolemic, circulatory, or septic shock. In such illnesses, inadequate oxygen supply indicated by lower tissue oxygen saturation (1), micro-circulatory dysfunction (2), metabolic acidosis (3), and blood lactate levels (4) correlates with worse intensive care unit outcome. Early and aggressive treatment of critically ill patients suffering from circulatory failure is associated with increased survival (5, 6), highlighting the need for monitoring methods capable of early detection. During compensated shock, whole-body tissue oxygenation is heterogeneous as systemic responses redirect blood flow to the brain and heart at the expense of organs such as the gut (7). Therefore, monitoring regional oxygenation of compromised organs may provide earlier warning of circulatory distress compared with commonly monitored systemic parameters such as heart rate, urine output, central venous pressure, arterial blood pressure, and serum lactic acid (8).

Splanchnic circulation is among the first to be compromised during shock, raising the possibility that, with proper monitoring technology, it may serve as the “canary of the body” (9). Decreases in splanchnic perfusion may accelerate critical illness and postoperative morbidity due to mucosal hypoperfusion and increased permeability to bacteria or toxins (10, 11). Thus, monitoring oxygenation of tissues supplied by the splanchnic circulation may enable earlier interventions to slow progression of morbidities related to hypoperfusion or sepsis.

Gastric tonometry, which measures intragastric carbon dioxide partial pressures, may provide a means of monitoring adequacy of splanchnic blood flow and is reported to be a prognostic indicator in patients undergoing cardiac surgery (12), admitted to the intensive care unit or in sepsis (13), or with acute cardiorespiratory failure (14). However, whereas resuscitation after induced abnormalities in gastric tonometry has shown promise in animal studies (15–17), prospective studies of protocols aimed at improving splanchnic circulation have not consistently shown patient outcome benefit (18–22). Use of gastric tonometry has been impeded partially by confounding factors such as the effects of temperature (23) and pH (24) on hemoglobin affinity for CO2, and due to the discontinuous measurement of the method, which can take more than 10 min to acquire. More direct measurements of organ perfusion could offer improved monitoring of splanchnic circulation.

Recent advances in hemoglobin oximetry technologies offer the ability to directly assess organ oxygenation and perfusion. One such Food and Drug Administration–approved device (T-STAT 303; Spectros Corporation, Portola Valley, Calif) uses visible light spectroscopy (VLS) to measure capillary hemoglobin oxygen saturations. Unlike pulse oximetry, VLS maintains a stable measurement of local microvascular hemoglobin oxygen saturation (StO2) even during ischemia (25, 26). Visible light spectroscopy sensors have been developed for sampling of tissues such as the buccal mucosa, intestinal or esophageal wall, skin, and blood.

To address the need for better clinical monitoring of splanchnic tissue oxygenation in the critical care setting, we measured the effect of acute reductions in splanchnic blood flow, systemic hypoxia, and hemorrhagic stress on various modes of oximetry monitoring in newborn lambs. We hypothesized that esophageal StO2 would demonstrate a direct relationship to changes in mesenteric artery flow during lower-body ischemia and hemorrhagic insult. We further hypothesized that esophageal StO2 would provide an earlier indication of systemic hypoxia than the other modes of monitoring.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Loma Linda University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Newborn lambs (n = 5) aged 5 to 15 days were intubated following intravenous injection of propofol (3.5 mg · kg−1). Anesthesia was maintained with 2% inspiratory isoflurane throughout surgical instrumentation. Following instrumentation, anesthesia was maintained with ketamine (0.1 mg · kg−1 · h−1). Lambs were paralyzed with vecuronium (0.1 mg · kg−1 · h−1) and mechanically ventilated with 50% O2 to maintain normocapnia (end-tidal PCO2 35–40 mmHg) throughout the experiment. Animals were instrumented with a brachial artery catheter for measurement of arterial blood gases and pressure, a brachial vein catheter for administration of intravenous medications, and a rectal temperature probe. A snare occluder was placed on the descending aorta superior to the diaphragm via open thoracotomy to enable reversible and graded aortic occlusions. For measurement of blood flow to the upper gastrointestinal organs, including the esophagus, a transonic flow probe (Transonic Systems, Inc, Ithaca, NY) was placed on the left ruminal mesenteric artery, which is the first trunk off of the aorta below the diaphragm. An oximetric central venous catheter (PediaSat Oximetry Catheter; Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, Calif) was inserted in the jugular vein and advanced to the vena cava to continuously monitor central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2). A VLS esophageal probe (Spectros CTH-060-END 2M) that emits and samples light at an angle parallel to the long axis of the probe was introduced orally and advanced to the lower esophagus to measure StO2. A VLS probe was also positioned to sample the buccal mucosa (Spectros CTH-060-ORA). After completion of the study protocols, the animal was killed via intravenously administered Euthasol (Virbac, Inc, Ft Worth, Tex) bolus, and catheter and probe positions were verified via autopsy.

Interventions

Following a 10-min period of baseline measurements, each animal was subjected to a sequence of regional and global ischemic insults. Regional splanchnic insult was induced by graded mesenteric flow decrease caused by three separate reversible occlusions of the descending aorta immediately above the diaphragm graded to target 50%, 75%, and nearly 100% reductions in left ruminal mesenteric artery blood flow. Each flow decrease was maintained for 5 min followed by 5 min of reperfusion recovery. Global hypoxic insult was induced by ventilation with 10% O2 in a balance of nitrogen for 5 min, followed by a 5-min period of recovery with ventilation at 100% O2. Finally, hemorrhagic insult was induced in five animals by removing an adequate volume of blood from an indwelling catheter into heparinized 60-mL syringes to achieve a 40% reduction in arterial pressure that was maintained for 5 min. The withdrawn blood was then reinfused within a 2-min period followed by continued recording of all modes of monitoring for 6 min after blood reinfusion.

Data analysis

Esophageal StO2, buccal StO2, and ScvO2 were monitored and recorded at 12-s intervals throughout the study protocol period. Mesenteric blood flow and arterial blood pressure were recorded at 200 Hz using an analog-to-digital converter (Powerlab 16; ADInstruments, Inc, Colorado Springs, Colo) and resampled to 12-s intervals following completion of the experiment (LabChart Pro v6.1.3 for Mac OS X; ADInstruments, Inc). Significant changes with time were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures and Bonferroni post hoc analysis where appropriate (Prism 5; GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, Calif). Relationships between mesenteric flow and the different modes of monitoring during the graded aortic occlusion and hemorrhage protocols were assessed by linear regression analysis (Prism 5). A complete listing of the linear regression results (slopes and R2 values) is shown in Tables 1 and 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, at http://links.lww.com/SHK/A161. Sensitivity power analysis of the data following completion of the study (G*Power v.3.1.2; University of Dusseldorf, Dusseldorf, Germany) indicated that the study was adequately powered to detect changes of 24% or greater in each of the modes of monitoring when n = 5. Data are presented as mean ± SE unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Regional splanchnic insult

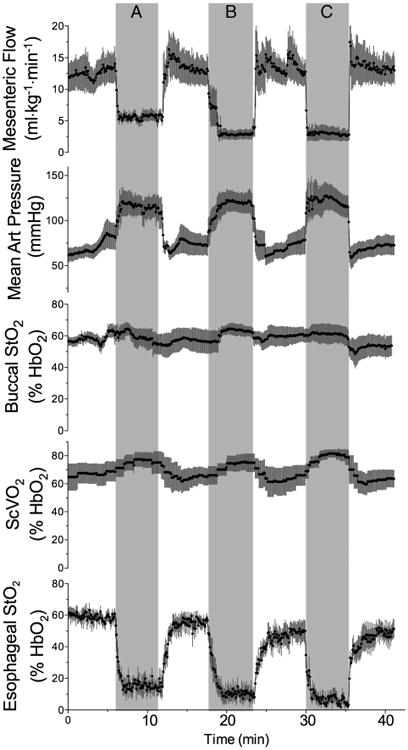

The effects of 5-min graded occlusions of the descending aorta on mesenteric flow, brachial artery pressure, ScvO2, and StO2 sensor measurements are shown in Figure 1. Before the insult, mean arterial blood pressure was 73 ± 8 mmHg, and baseline arterial PO2, PCO2, and pH were 133 ± 16 mmHg, 37 ± 5 mmHg, and 7.35 ± 0.03, respectively. Mesenteric artery flow was decreased from a baseline average of 12.6 ± 6.3 mL · kg−1 · min−1 to 5.3 ± 2.3, 2.5 ± 1.4, and 2.2 ± 1.4 mL · kg−1 · min−1 during the 50%, 75%, and 100% occlusions, respectively (P < 0.05 for each decrease, one-way ANOVA). Esophageal StO2 was directly related to mesenteric flow with a slope of 0.54 ± 0.01%·mL · kg−1 · min−1 (R2 = 0.41) and decreased significantly (P < 0.05, oneway ANOVA) at the onset of each graded occlusion. As expected, aortic occlusion directed a larger portion of cardiac output to the upper body, resulting in increased brachial artery blood pressure. Both buccal StO2 and ScvO2 were inversely related to mesenteric flow during aortic occlusion, with slopes of −0.55 ± 0.02 and −0.16 ± 0.01%·mL · kg−1 · min−1, respectively, although the overall effect was small (R2 = 0.16 and 0.07, respectively). Although ScvO2 tended to rise during occlusions and fall during reperfusion, the changes over time were not statistically significant (one-way ANOVA).

Fig 1.

Time course of changes in mesenteric artery flow, mean brachial artery blood pressure, buccal StO2, ScvO2, and esophageal StO2 in response to 50% (A), 75% (B), and 100% (C) graded occlusion of the descending aorta (n = 5).

Global hypoxic insult

The effects of 5 min of systemic hypoxia on mesenteric flow and the modes of monitoring are shown in Figure 2. Before the insult, mean arterial blood pressure was 78 ± 6 mmHg and baseline arterial PO2, PCO2, and pH were 130 ± 14 mmHg, 38 ± 4 mmHg, and 7.36 ± 0.02, respectively. At the end of the hypoxic insult, arterial PO2, PCO2, and pH were 42 ± 5 mmHg, 41 ± 4 mmHg, and 7.34 ± 0.03, respectively. Of the oximetry methods, esophageal StO2 was the first to detect a decrease in oxygenation, falling significantly within 1 min of the initiation of the hypoxic insult (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Buccal StO2 decreased significantly within 3 min of the start of hypoxia, whereas ScvO2 did not change significantly during the hypoxic insult. Mean arterial blood pressure and mesenteric flow were also not significantly altered by the hypoxic insult (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Fig 2. Effect of systemic hypoxia (shaded area, fractional inspired O2 = 0.10) on arterial blood pressure, mesenteric artery flow, and the three modes of oximetry monitoring.

Esophageal StO2 decreased significantly within seconds of the onset of hypoxia (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA); buccal StO2 decreased significantly near the end of the hypoxic insult (P< 0.05, one-way ANOVA), and ScvO2 did not change significantly during hypoxia (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, n = 5).

Hemorrhagic insult

The effects of acute hemorrhage on mesenteric flow, brachial arterial pressure, and oximetry monitoring are shown in a representative animal in Figure 3A. Before the insult, mean arterial blood pressure was 72 ± 9 mmHg, and baseline arterial PO2, PCO2, and pH were 138 ± 17 mmHg, 38 ± 6 mmHg, and 7.32 ± 0.04, respectively. The volume of withdrawn blood that was required to lower arterial blood pressure of each animal by 40% varied, and the time needed to accomplish sufficient blood withdrawal varied between 4 and 12 min. All modes of oximetry and arterial blood pressure demonstrated a significant direct relationship to mesenteric artery flow (P < 0.0001, Fig. 3B). The 95% confidence intervals derived from the linear regression of each mode of monitoring versus mesenteric artery flow are plotted against mesenteric flow in Figure 3C and illustrate that the modes can be ranked by predictive value for mesenteric flow as follows: brachial arterial pressure (slope = 0.67 ± 0.01, R2 = 0.61) > buccal StO2 (slope = 0.35 ± 0.01, R2 = 0.65) > esophageal StO2 (slope = 0.74 ± 0.02, R2 = 0.42) > ScvO2 (slope = 0.24 ± 0.04, R2 = 0.12). Notably, esophageal flow demonstrated the greatest decrease from baseline levels, falling by 69% ± 4% of baseline during the hemorrhagic insult compared with mesenteric flow (56% ± 8% of baseline), blood pressure (47% ± 7% of baseline), buccal StO2 (37% ± 12% of baseline), and ScvO2 (10% ± 11% baseline) (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA).

Fig 3. Effect of hemorrhage on mesenteric flow, brachial arterial pressure, and the three methods of oximetry.

A, Results from a representative animal. Withdrawal of blood began at time 0 and ended when arterial blood pressure had decreased to ∼60% of baseline (arrow). B, Linear regression using data from five animals. Mesenteric flow changes in response to hemorrhage were directly related to changes in buccal StO2 (slope = 0.35 ± 0.01, R2 = 0.65), brachial arterial pressure (slope = 0.67 ± 0.01, R2 = 0.61), and esophageal StO2 (slope = 0.74 ± 0.02, R2 = 0.42) and weakly related to changes in ScvO2. Dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals (n = 5). C, Absolute 95% confidence interval from the linear regressions plotted in B, from 25% to 175% of baseline mesenteric artery flow.

Responses to reinfusion of the withdrawn blood are shown in Figure 4. Of the parameters shown, only esophageal StO2 demonstrated a significant change over the 6 min of data recorded following reinfusion.

Fig 4. Effect of reinfusion of blood following hemorrhagic insult on mesenteric flow, brachial arterial pressure, and the three methods of oximetry.

Reinfusion of blood was completed at time 0. There were no significant changes in mesenteric flow, mean arterial blood pressure, buccal StO2, or ScvO2, whereas esophageal StO2 had increased significantly within 4 min of reinfusion (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, n = 5).

Discussion

The present experiments were designed to assess, in a newborn lamb model, the ability of esophageal and buccal StO2, and ScvO2 oximetry monitoring to detect decreased mesenteric artery blood flow, systemic hypoxia, and acute hemorrhage. We found that esophageal StO2 was correlated with decreases in mesenteric artery flow. Furthermore, esophageal StO2 changed rapidly during ischemic insults and thus appears to be a sensitive means of detecting systemic hypoxia and acute hemorrhage in this model.

Visible light spectroscopy has been used to detect decreased esophageal oxygenation in patients receiving antegrade cerebral perfusion during complex neonatal heart surgery (27), rapid decreases in StO2 during systemic hypoxia and mesenteric ischemia in newborn piglets (26), and decreased StO2 in patients with known bowel ischemia that resolved with successful treatment (28). The current findings in newborn lambs are in agreement with these previous reports, demonstrating that changes in esophageal StO2 correlate closely with changes in splanchnic blood flow and oxygenation.

Regional ischemia

We observed an almost immediate decrease in esophageal StO2 values with the onset of each degree of aortic occlusion and rapid restoration to baseline StO2 values when flow was restored. This finding demonstrates that esophageal StO2 provides an indication of acute decreases in splanchnic blood flow. ScvO2 values showed a slight increase during each occlusion, likely due to the redistribution of blood flow and oxygen delivery to the upper body during the regional insult. In fact, although ScvO2 tended to decrease as perfusion of the lower body resumed upon restoration of aortic flow, the changes were not statistically significant, likely due to dilution of the less oxygenated lower-body blood with venous blood from the upper body before reaching the ScvO2 probe. This effect also likely explains why there was not a significant change in buccal StO2 during these periods of graded occlusion, as buccal capillary bed saturation in this condition would be less affected than the gut because of sudden increases in upper-extremity blood flow. Although buccal StO2 is reported to be a useful surrogate measurement of gastric blood flow (29, 30), our results suggest that esophageal StO2 offers better detection of blood flow redistribution that may occur in response to cardiovascular distress.

Systemic hypoxia and acute hemorrhage

Although occlusion of the descending aorta is a useful means of demonstrating the correlation between esophageal StO2 and mesenteric flow, it is perhaps a less clinically relevant model of systemic cardiovascular compromise than either global hypoxia or hypovolemia, when sympathetic responses are expected to stimulate vasoconstriction in the splanchnic circulation. In the present experiments, esophageal StO2 demonstrated a rapid response to systemic hypoxia and decreased in a nearly colinear manner with hemorrhage-related mesenteric flow decrease. This supports the idea that, under stress, mesenteric blood flow and thus oxygen delivery decrease, and this decrease can be detected by esophageal StO2, providing an early marker of splanchnic flow decreases during hemorrhage. Notably, although arterial blood pressure and buccal StO2 were more closely correlated to mesenteric artery flow than was esophageal StO2, esophageal StO2 demonstrated a greater decrease from baseline levels than the other modes of monitoring as well as a significant return to baseline levels during reinfusion of the withdrawn blood. The rapid recovery of esophageal StO2 is consistent with previous work in newborn pigs and suggests that this mode of monitoring may serve as a sensitive marker of recovery from hemorrhagic stress (31). Consistent with previous reports that buccal capnometry is useful for grading hemorrhagic shock (32), we also found significant decreases in buccal StO2 during hypoxia and hypovolemia, suggesting this monitoring method may also be useful. It is important to note that esophageal StO2 values decreased within seconds of the hypoxic event compared with a delay of several minutes for changes in ScvO2 or buccal StO2 values to occur. This further supports the idea that, under stress, mesenteric oxygen delivery may decrease, and this decrease can be detected by esophageal StO2.

Our findings suggest that systemic measures such as ScvO2 are relatively poor indicators of splanchnic ischemia during acute episodes of decreased aortic blood flow, systemic hypoxia, and hypovolemic shock. This is likely due to a significant reduction in peripheral circulating volume as a result of either the mechanical occlusion of the aorta or the sympathetic response to hypoxia and hypovolemia. Consequently, blood pressure tends to be maintained, and oxygenation of the tissues that are still being perfused remains high enough that changes in mixed venous oxygenation are minor. These findings underscore the need for methods that monitor peripheral tissues directly as a means of detecting when the body has initiated defensive responses to cardiovascular stress.

Study limitations

As described in Materials and Methods, each lamb was subjected to all three types of hypoxic/ischemic stress in the same sequence. Although blood gases and mean arterial blood pressures returned to normal during the recovery, little is known about whether preconditioning effects of the aorta occlusions may have altered the responses to subsequent hypoxia and hemorrhagic stress. Although many studies have demonstrated that ischemic preconditioning can result in protection of specific organs against damage from a subsequent severe ischemic insult, relatively little is known about the effects of preconditioning on systemic blood flow and tissue oxygenation responses during subsequent stresses such as the ones used in our study. In addition, we did not measure hemoglobin during the insults, preventing calculation of absolute changes in oxygen delivery during each insult. However, it is reasonable to infer that hemoglobin did not change during either aortic occlusion or hypoxic insults as blood or intravenous fluid was not withdrawn or administered during these insults. Thus, the decreased flow and low PaO2 measured during these respective insults reflect decreased oxygen delivery to the tissues. As blood withdrawal caused decreased mesenteric blood flow, it is similarly reasonable to infer that mesenteric oxygen delivery fell during that insult.

This study does not include some important noninvasive modes of hemodynamic monitoring used clinically, such as pulse oximetry and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). In our lamb model, both pulse oximetry and NIRS have provided only intermittent, insufficient data likely due to anatomical differences such as skin thickness, subcutaneous fat deposition, and wool. Pulse oximetry is a widely used monitoring method because of its ease of use and relatively low cost. Near-infrared spectroscopy has been used to monitor oxygenation in many tissues including the kidneys, viscera, muscle, brain, and thenar eminence (33). Although both pulse oximetry and NIRS may be confounded by factors such as temperature, patient position, fat deposition, and comorbidities, they can be useful monitoring tools, and clinical studies are needed to examine whether esophageal oximetry offers advantages over these noninvasive methods.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that esophageal StO2 monitoring accurately indicates acute decreases in blood flow to the mesentery with reliable incremental associations between decreases in mesenteric artery blood flow and esophageal StO2. In addition, acute systemic hypoxia and hypovolemia are both reflected by decreases in esophageal StO2 within seconds of the insult. The correlation of decreases in lower esophageal StO2 with decreases in mesenteric blood flow suggests that direct monitoring of esophageal tissue saturation may allow for earlier detection and potential intervention in stress states such as hypoperfusion or hypoxia. Further evaluation of this monitoring tool is warranted in a clinical setting where it may enable earlier responses to cardiovascular compromise.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Shannon Bragg and Jonathon Ross for their expert technical assistance and Michelle Spencer for her editing assistance.

This project was supported in part by the Department of Anesthesiology; the Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics; and the Center for Perinatal Biology, Loma Linda University School of Medicine. These experiments were partially supported by grants from the American Heart Association (to A.B.B.) and National Institutes of Health HL095973 (to A.B.B).

Footnotes

Monitoring materials for this study were provided as unrestricted donations from Edwards Lifesciences and Spectros Corporation. These entities had no input into study design, data analysis, or manuscript preparation.

None of the authors have any conflict of interest to report.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.shockjournal.com).

References

- 1.Leone M, Blidi S, Antonini F, Meyssignac B, Bordon S, Garcin F, Charvet A, Blasco V, Albanese J, Martin C. Oxygen tissue saturation is lower in nonsurvivors than in survivors after early resuscitation of septic shock. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(2):366–371. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae72d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trzeciak S, Dellinger RP, Parrillo JE, Guglielmi M, Bajaj J, Abate NL, Arnold RC, Colilla S, Zanotti S, Hollenberg SM. Early microcirculatory perfusion derangements in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: relationship to hemodynamics, oxygen transport, and survival. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(1):88–98. 98e1–98e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noritomi DT, Soriano FG, Kellum JA, Cappi SB, Biselli PJ, Liborio AB, Park M. Metabolic acidosis in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a longitudinal quantitative study. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2733–2739. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0b013e3181a59165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jansen TC, van Bommel J, Bakker J. Blood lactate monitoring in critically ill patients: a systematic health technology assessment. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10):2827–2839. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a98899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Knoblich BP, Jacobsen G, Muzzin A, Ressler JA, Tomlanovich MC. Early lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1637–1642. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000132904.35713.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ba ZF, Wang P, Koo DJ, Cioffi WG, Bland KI, Chaudry IH. Alterations in tissue oxygen consumption and extraction after trauma and hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(8):2837–2842. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marik PE. Regional carbon dioxide monitoring to assess the adequacy of tissue perfusion. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11(3):245–251. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000158091.57172.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dantzker DR. The gastrointestinal tract. The canary of the body? JAMA. 1993;270(10):1247–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chieveley-Williams S, Hamilton-Davies C. The role of the gut in major surgical postoperative morbidity. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1999;37(2):81–110. doi: 10.1097/00004311-199903720-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackland G, Grocott MP, Mythen MG. Understanding gastrointestinal perfusion in critical care: so near, and yet so far. Crit Care. 2000;4(5):269–281. doi: 10.1186/cc709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mythen MG, Webb AR. Perioperative plasma volume expansion reduces the incidence of gut mucosal hypoperfusion during cardiac surgery. Arch Surg. 1995;130(4):423–429. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430040085019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creteur J, De Backer D, Sakr Y, Koch M, Vincent JL. Sublingual capnometry tracks microcirculatory changes in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(4):516–523. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakob SM, Parviainen I, Ruokonen E, Kogan A, Takala J. Tonometry revisited: perfusion-related, metabolic, and respiratory components of gastric mucosal acidosis in acute cardiorespiratory failure. Shock. 2008;29(5):543–548. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31815d0c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellstrom A, Mansson P, Jonsson K, Hartmann M. Measurements of subcutaneous tissue PO2 reflect oxygen metabolism of the small intestinal mucosa during hemorrhage and resuscitation. An experimental study in pigs. Eur Surg Res. 2009;42(2):122–129. doi: 10.1159/000193295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan JJ, Cohen MJ, Rosenthal G, Haitsma IK, Morabito DJ, Derugin N, Knudson MM, Manley GT. Refining resuscitation strategies using tissue oxygen and perfusion monitoring in critical organ beds. J Trauma. 2009;66(2):353–357. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318195e222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guzman JA, Dikin MS, Kruse JA. Lingual, splanchnic, and systemic hemodynamic and carbon dioxide tension changes during endotoxic shock and resuscitation. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98(1):108–113. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00243.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Splanchnic hypoperfusion-directed therapies in trauma: a prospective, randomized trial. Am Surg. 2005;71(3):252–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holm C, Horbrand F, Mayr M, Henckel von Donnersmarck G, Muhlbauer W. Assessment of splanchnic perfusion by gastric tonometry in patients with acute hypovolemic burn shock. Burns. 2006;32(6):689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cancio LC, Kuwa T, Matsui K, Drew GA, Galvez E, Jr, Sandoval LL, Jordan BS. Intestinal and gastric tonometry during experimental burn shock. Burns. 2007;33(7):879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palizas F, Dubin A, Regueira T, Bruhn A, Knobel E, Lazzeri S, Baredes N, Hernandez G. Gastric tonometry versus cardiac index as resuscitation goals in septic shock: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2009;13(2):R44. doi: 10.1186/cc7767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubin A, Pozo MO, Casabella CA, Palizas F, Jr, Murias G, Moseinco MC, Kanoore Edul VS, Palizas F, Estenssoro E, Ince C. Increasing arterial blood pressure with norepinephrine does not improve microcirculatory blood flow: a prospective study. Crit Care. 2009;13(3):R92. doi: 10.1186/cc7922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman MV, Woolf RL, Bennett-Guerrero E, Mythen MG. The effect of hypothermia on calculated values using saline and automated air tonometry. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16(3):304–307. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2002.124138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakob SM, Kosonen P, Ruokonen E, Parviainen I, Takala J. The Haldane effect—an alternative explanation for increasing gastric mucosal PCO2 gradients? Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(5):740–746. doi: 10.1093/bja/83.5.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benaron DA, Parachikov IH, Cheong WF, Friedland S, Rubinsky BE, Otten DM, Liu FW, Levinson CJ, Murphy AL, Price JW, et al. Design of a visible-light spectroscopy clinical tissue oximeter. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10(4):44005. doi: 10.1117/1.1979504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benaron DA, Parachikov IH, Friedland S, Soetikno R, Brock-Utne J, van der Starre PJ, Nezhat C, Terris MK, Maxim PG, Carson JJ, et al. Continuous, noninvasive, and localized microvascular tissue oximetry using visible light spectroscopy. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(6):1469–1475. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200406000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heninger C, Ramamoorthy C, Amir G, Kamra K, Reddy VM, Hanley FL, Brock-Utne JG. Esophageal saturation during antegrade cerebral perfusion: a preliminary report using visible light spectroscopy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16(11):1133–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedland S, Benaron D, Coogan S, Sze DY, Soetikno R. Diagnosis of chronic mesenteric ischemia by visible light spectroscopy during endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(2):294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pernat A, Weil MH, Tang W, Yamaguchi H, Pernat AM, Sun S, Bisera J. Effects of hyper- and hypoventilation on gastric and sublingual PCO(2) J Appl Physiol. 1999;87(3):933–937. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.3.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Povoas HP, Weil MH, Tang W, Moran B, Kamohara T, Bisera J. Comparisons between sublingual and gastric tonometry during hemorrhagic shock. Chest. 2000;118(4):1127–1132. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Salam Z, Johnson S, Abozaid S, Bigam D, Cheung PY. The hemodynamic effects of dobutamine during reoxygenation after hypoxia: a dose-response study in newborn pigs. Shock. 2007;28(3):317–325. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318048554a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cammarata GA, Weil MH, Castillo CJ, Fries M, Wang H, Sun S, Tang W. Buccal capnometry for quantitating the severity of hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2009;31(2):207–211. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31817c0eb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hampton DA, Schreiber MA. Near infrared spectroscopy: clinical and research uses. Transfusion. 2013;53(Suppl 1):52S–58S. doi: 10.1111/trf.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.