Figure 2. Gr68a expression in the male foreleg is required for CH503 detection.

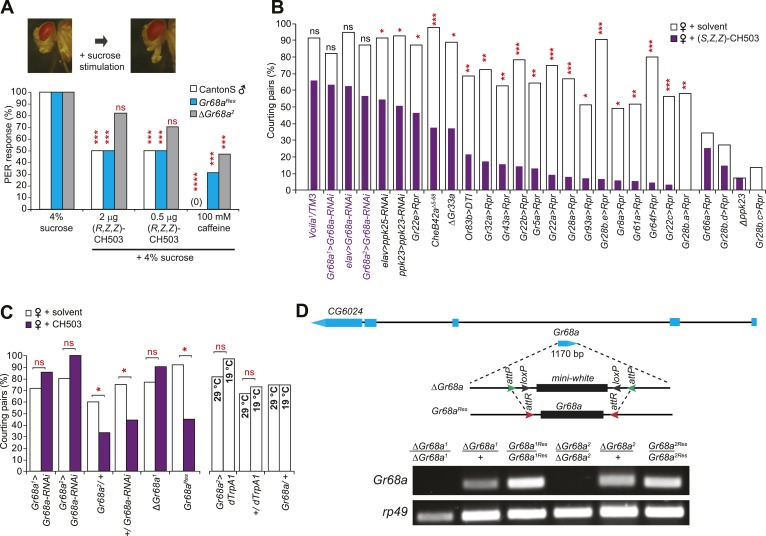

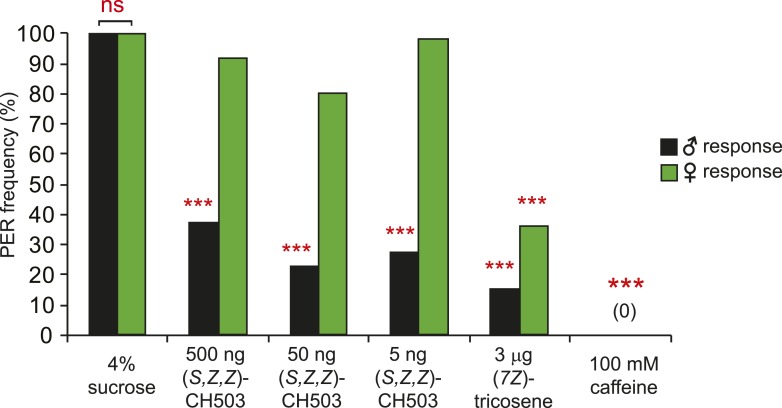

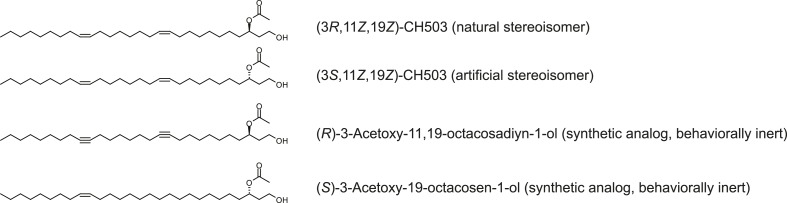

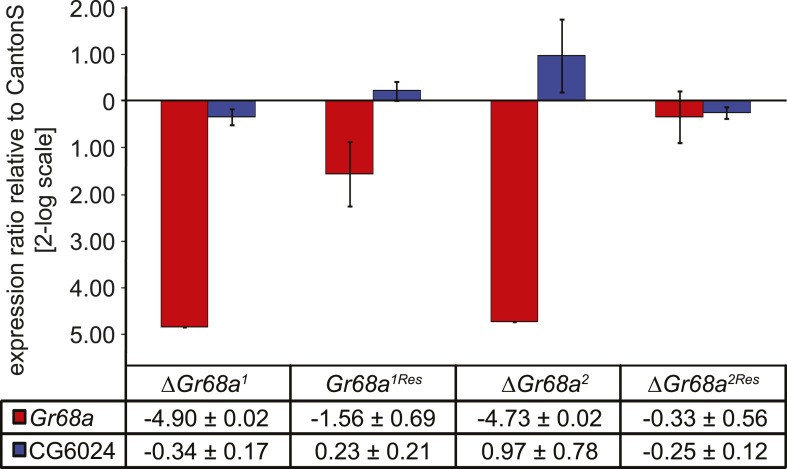

(A) Simultaneous stimulation of the male foreleg with 4% sucrose and CH503 or caffeine significantly inhibits the proboscis extension reflex (PER; shown in pictures) in CantonS males (white). The PER suppression was not observed in ΔGr68a mutant flies (gray) but was restored upon re-introduction of the Gr68a gene (Gr68aRes; blue). For each genotype, the response to each test compound was compared to the response to sucrose alone. N = 18, Fisher's exact probability test, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns: not significant. (B) A behavioral screen targeting foreleg-specific gustatory receptor neurons, pheromone receptors, and a pheromone binding protein reveals that Gr68a is a candidate receptor for detecting (S, Z, Z)-CH503. The number of flies exhibiting courtship in response to the pheromone (purple) was compared to the response to a solvent-perfumed female (white). For some genotypes (far right of graph), the basal courtship level was too low to observe a courtship suppression effect. N = 12–73, Fisher's exact probability test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. (C) Silencing Gr68a expression with RNAi or genetic deletion resulted in a loss of sensitivity to CH503. The courtship suppression response was unaltered in parental control lines and restored upon re-introduction of the gene into the mutant. Hyperactivation of Gr68a-expressing neurons using dTrpA1 at the activation temperature (29°C) resulted in a slight but non-significant courtship suppression compared to the inactive temperature (19°C). Parental control lines exhibited no difference in courtship behavior at 29°C or 19°C. N = 12–37, Fisher's exact probability test, *p < 0.05, ns: not significant. (D) (Top) A schematic of the Gr68a gene locus shows that the single coding exon (blue) resides within the intronic region (black) of another gene, CG6024. (middle) The homologous recombination strategy for deletion and rescue of Gr68a involves replacement of the endogenous gene with the mini-white marker using recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE). Genomic rescue of Gr68a is accomplished by exchanging mini-white via RMCE with the Gr68a sequence. (Bottom) Analysis by semi-quantitative PCR of genomic DNA shows the complete absence of Gr68a expression in two homozygous mutant alleles and successful rescue in the respective Gr68aRes lines. Rp49 expression is used as a loading control. CG6024 expression is not changed in mutant or rescue lines (Figure 2—figure supplement 3).