Abstract

Primary Prevention of Sudden Cardiac death in post-infarction patients especially those with ejection fraction less than 35% is best achieved by implantable defibrillator. However, the cost of Quality Adjusted Life Years saved is $ 50,000–70,000, makes implantable defibrillators not an easily acceptable option when preventing SCD in a significant number of patients with low ejection fraction of 35 percent. In, addition excessive dependence on ejection fraction, excludes a large number of postinfarction patients with ejection fraction more than 35 percent, or patients with existing but not known heart disease. The two complementary strategies based on Public Health approach and Home AED approach and strengthening the program of Bystander CPR and AED application of publically available AED may be a better way for Primary Prevention of SCD in more number of patients. These approaches may be considered seriously to reduce sudden cardiac death in India, however, it needs to be proven.

Keywords: Primary, Prevention, Sudden, Cardiac, Death

1. Definition

Death from cardiac arrest occurring within one hour of onset of symptoms is referred to as Sudden Cardiac Death or SCD. It is characterized by unexpected cardiovascular collapse from an underlying cardiac cause. Primary Prevention is preventing SCD in people who are at risk for sudden cardiac death, but have never had cardiac arrest which can lead to sudden cardiac death.

2. Epidemiology

Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) from cardiac arrest is the most common cause of death worldwide, accounting for more than 50 percent of all cardiovascular deaths worldwide. There are approximately 166,200–250,000 out-of hospital SCD annually in the United States.1 This accounts for about 38–50% of all cardiac deaths. The median survival from SCD is only 6.4%.1 In the majority of patients who suffer SCD, the underlying mechanism is Ventricular fibrillation. While effective cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can improve survival, the most effective treatment of ventricular fibrillation is very early defibrillation.2,3

3. Who is at high risk for SCD

Primary Prevention of SCD is best possible if we can identify those people who are at risk for SCD.

Persons at the greatest risk of sudden cardiac death are those with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Many primary preventions trials including MADIT-1, MADIT-2, MUSTT, and SCD-HeFT4–7 have shown that patients with previous myocardial infarction with left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 35% had 2 year all-cause mortality of 22–32%. The SCD-HeFT trial also included patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and found similar mortality risk.

4. Interestingly, a large majority of SCDs happen in people with no “known” pre-existing heart disease

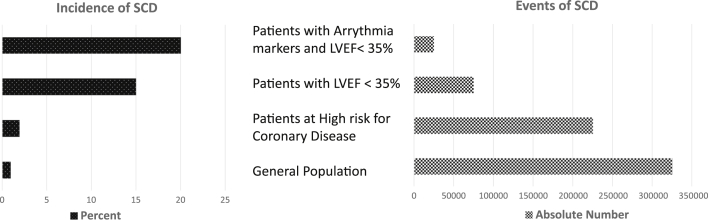

In fact, most SCDs in absolute terms occur in patients with no known pre-existing known heart disease. As seen in Fig. 1, it is evident that the incidence of SCD is about 20% per year in patients with heart failure and those with arrhythmia markers, compared with about 1–2% in general population, who are patients with no “known” pre-existing heart disease. On the other hand the absolute numbers of SCD are significantly much higher about 325,000 per in year in the general population compared with just about 20,000 in patients with heart failure and arrhythmia markers.8

Fig. 1.

Estimates of Incidence and Events of SCD in General population and patients with heart disease.

5. What do the guidelines state about primary prevention of sudden cardiac death?

Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICD) is recommended for primary prevention of SCD, in patients with ischemic or non-ischemic cardio-myopathy, with left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 35% with the following exclusions.9,10

-

1.

Within 3 months of myocardial re-vascularization

-

2.

Within 40 days of myocardial infarction

-

3.

Within 90 days of initial diagnosis of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy

-

4.

Cardio-genic shock

6. What are the problems with current guidelines?

-

1.

Excludes a large number of patients at risk, who have not yet been identified to have heart disease, as shown in Fig. 1

-

2.

High Cost of therapy. The estimated cost range of quality adjusted year of life saved is $34,000-$ 70, 200 in the MADIT and SCD-HeFT trial.11 This excludes a lot of people

-

3.

Excessive dependence of left ventricular ejection fraction in post-infarction patients. Excludes post-infraction patients with ejection fraction more than 35 percent.

7. What is the alternative to the guidelines?

The two complementary alternate strategies mentioned below, which need to be strengthened/reinforced to make primary prevention of sudden cardiac death possible in more people, include.

-

1.

Public Health Approach: Primary Prevention of SCD by Bystander CPR (cardio-pulmonary resuscitation) and Publically Accessible AED in General population. It has been shown that there is a 74% chance of survival from SCD, if the AED is applied within 3 min of onset of collapse.2 The Public Access Defibrillation trial12 studied the benefit of early defibrillation, and has shown that with effective Bystander CPR and early application of available Automated External Defibrillator by Bystanders, the survival from SCD in general population can be significantly improved. The trial included 19000 volunteer responders in 993 community units, which included shopping malls, apartment complexes and hotels. Nearly 30% volunteers were just high school students. In case of cardiac arrest the volunteers were notified thru pager or telephone. The study showed nearly 30% survival with CPR and early defibrillation by a publically accessible defibrillator compared with only 15% with CPR alone. All patients received continuation of resuscitative efforts by trained paramedic personnel of the emergency medical services after their arrival.

We in India, should also pay strong emphasis on building Bystander CPR programs, and train lay people in use of AED. This is probably the most cost effective way to improve survival from first episode of cardiac arrest or those with no known pre-existing heart disease (which may be plenty in India).

-

2.

Home AED Approach: Primary Prevention of SCD by Family member performed CPR and Home AED in patients at high risk of SCD. While impressive results have been obtained by publicly available AED, the effect of such programs is limited, since, studies have shown that 80% of all out-of hospital SCDs occur at home.13,14 Unfortunately, the successful resuscitation of SCD at home is extremely poor at only 2%.14 The Home AED Trial (HAT) reported in 2008,15 which included 7001 patients, randomized to the Study group, those recommended initial treatment of SCD at home by Family member performed CPR and AED Application or the Control group with recommended initial resuscitation solely attempted by trained paramedics of the Emergency Medical Services called in case of SCD. Patients who initially received resuscitative attempts including AED use by family members, received continued resuscitative efforts by paramedics of the emergency medical services on arrival. It was found that the Family member performed CPR and AED use was successful in preventing sudden cardiac death in about 12% patients who suddenly collapsed at home. This was higher than the 2% survival in other studies,15 of survival from SCD at home. The study however, did not find show significant reduction in total mortality rate with the strategy of initial Family member performed CPR and AED use (mortality rate 6.4%), compared with CPR and AED use by conventional community based emergency medical services or the Control group (mortality rate 6.5%), which were called in case of sudden collapse. According to the authors, the lack of benefit in the study was due to factors which included, a low or less than 1 percent incidence of SCD, probably because the study only included post-infarction patients, who had ejection fraction more than 35% and thus were not candidates for ICD therapy. It remains to be seen if Home AED and family member performed CPR can prevent SCD in post-infarction patients or those with ejection fraction less than 35%, who cannot afford ICD therapy compared with community based emergency cardiac care services, in less industrialized or developing countries. This is especially important since, in many developing countries, the community based emergency cardiac care services are not as well developed or are overwhelmed or delayed due to traffic issues.

8. Conclusions

Primary Prevention of Sudden Cardiac death in post-infarction patients especially those with ejection fraction less than 35% is best achieved by implantable defibrillator. However, the cost of Quality Adjusted Life Years saved is $ 50,000–70,000, makes implantable defibrillators not an easily acceptable option when preventing SCD in a significant number of patients with low ejection fraction of 35 percent. In, addition excessive dependence on ejection fraction, excludes a large number of post-infarction patients with ejection fraction more than 35 percent, or patients with existing but not known heart disease. The two complementary strategies based on Public Health approach and Home AED approach and strengthening the program of Bystander CPR and AED application of publically available AED may be a better way for Primary Prevention of SCD in more number of patients. This requires training more lay people, students, family and friends in CPR and AED use. This training can be easily imparted even to middle school and high school children and adults. American Heart Association and other organizations have designed simple and effective training courses in CPR and AED use for lay people. Home AED application and Family member performed CPR in post-infarction patients with mildly reduced ejection fraction (more than 35%) is an alternative, however, its superiority to community based emergency medical services has not been proven in the industrialized developed countries. It remains to be seen if Home AED use can be feasible in developing countries with less well organized or overwhelmed emergency medical services. Our Challenge to the current guidelines for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death, is to device strategies which are more cost-effective, which benefit more patients both with “known” and “not known” but pre-existing heart disease, taking into consideration our huge patient population, lack of good community based emergency medical services. We do however, have high population density homes where a Home AED or Public AED may be life-saving, but it needs to be proven.

Conflicts of interest

The author has none to declare.

References

- 1.Rosamond W., Flegal K., Furie G. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2008 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e24–e146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valenzuela T.D., Roe D.J., Nichol G., Clark L.L., Spaite D.W., Hardman R.G. Outcomes of rapid defibrillation by security officers after cardiac arrest in casinos. N Eng J Med. 2000;343:1206–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010263431701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White R.D., Bunch T.J., Hankins D.G. Evolution of a community-wide early defibrillation programme: experience over 13 years using police/fire personnel and paramedics as responders. Resuscitation. 2005;65:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MADIT-1, Moss A.J., Hall W.J., Cannom D.S. Improved survival with an implantable defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial Investigators. New Eng J Med. 1996;335:1933. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MADIT-2, Moss A.J., Zareba W., Hall W.J. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Eng J Med. 2002;346:877. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MUSTT, Buxton A.E., Lee K.L., Fisher J.D. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden cardiac death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multi-center Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Eng J Med. 1999;341:1882. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SCD-HeFT, Bardy G.H., Lee K.L., Mark D.B. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2005;352:225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myerburg R.J. Sudden cardiac death: exploring the limits of our knowledge. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:369–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities. Circulation. 2008;117:e350–e408. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DINAMIT trial, Hohnloser S.H., KucK K.H., Dorian P. Prophylactic use of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator after acute myocardial infarction. N Eng J Med. 2004;351:2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders G.D., Hlarky M.A., Owens D.K. Cost effectiveness of implantable cardioverter defibrillators. N Eng J Med. 2005;353:1471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Public Access Defibrillation Trial Investigators N Engl J Med. 2004;351:637–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisfeldt Myron L., Everson-Stewart Siobhan, Sitlani Colleen, for the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC) Investigators N Engl J Med. 2011;364:313–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris R.M., UK Heart Attack Study Collborative Group Cicumstances of out-of hospital cardiac arrest in patients with ischemic heart disease. Heart. 2005;91:1537. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.057018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bardy Gust H., Lee Kerry L., Mark Daniel B., for the HAT Investigator N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1793–1804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]